Abstract

Background

The kidneys maintain acid-base homeostasis through excretion of acid as either ammonium or as titratable acids (TA) that primarily use phosphate as a buffer. In CKD, ammoniagenesis is impaired, promoting metabolic acidosis. Metabolic acidosis stimulates phosphaturic hormones, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) in vitro, possibly to increase urine TA buffers, but this has not been confirmed in humans. We hypothesized that higher acid load and acidosis would associate with altered phosphorus homeostasis including higher urinary phosphorus, PTH and FGF-23.

Study Design

Cross-sectional

Setting & Participants

980 participants with CKD enrolled in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study

Predictors

Net acid excretion as measured in 24-hour urine, potential renal acid load (PRAL) estimated from food frequency questionnaire responses, and serum bicarbonate < 22 mEq/L

Outcome & Measurements

24h urine phosphorus and calcium; serum phosphorus, FGF-23, and PTH

Results

Using linear and log-linear regression adjusted for demographics, kidney function, comorbidities, body mass index, diuretic use and 24h urine creatinine, we found that 24h urine phosphorus was higher at higher net acid excretion, higher PRAL, and lower serum bicarbonate (each p<0.05). Serum phosphorus was also higher with higher net acid excretion and lower serum bicarbonate (each p=0.001). Only higher net acid excretion associated with higher 24h urine calcium excretion (p<0.001). Neither net acid excetion nor PRAL were associated with FGF-23 or PTH. PTH, but not FGF-23 (p=0.2), was 26% (95% CI, 13%-40%) higher in participants with a serum bicarbonate 22< vs ≥22 mEq/L (P<0.001). Primary results were similar if stratified by eGFR categories, or if adjusted for iothalamate GFR (n=359), total energy intake, dietary phosphorus or urine urea nitrogen, where available.

Limitations

Possible residual confounding by kidney function or nutrition; urine phosphorus was included in calculation of the titratable acid component of net acid excretion

Conclusions

In CKD, higher acid load and acidosis associates independently with increased circulating phosphorus and augmented phosphaturia, but not consistently with FGF-23 or PTH. This may be an adaptation that increases TA excretion, and thus helps maintain acid-base homeostasis in CKD. Understanding if administration of base can lower phosphorus requires testing in interventional trials.

Keywords: acid-base, acidosis, phosphorus, fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), parathyroid hormone (PTH), chronic kidney disease (CKD), phosphorus homeostasis, phosphorus excretion, FEPi, phosphaturic hormones, acid load, physiology, potential renal acid load (PRAL)

The major role of the kidneys is to maintain the internal milieu, including preserving acid-base and phosphorus homeostasis. In health, the kidney regulates acid-base balance by excreting fixed acids generated from nutrient metabolism 1,2, and phosphorus balance by excreting the absorbed load of ingested phosphorus 3. As kidney function declines in chronic kidney disease (CKD), both of these functions are compromised. To overcome lower acid excretion in the form of ammonium (NH4+), excretion of titratable acid in the form of monovalent phosphate (H2PO4-) may be relatively increased through reduction in urine pH or augmented phosphaturia 4-7. Additionally, to prevent hyperphosphatemia, fractional phosphorus excretion may be augmented by the phosphorus-regulatory hormones parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) 3. Thus, both of these processes occur in tandem during progressive kidney disease and may converge on urine phosphorus excretion as a critically regulated parameter (see Figure S1, available as online supplementary material). Nonetheless, few studies have evaluated the relationship between derangements in acid-base and derangements in phosphorus homeostasis in patients with CKD.

Several animal and in vitro models suggest that changes in acid-base status and acid load may affect phosphorus homeostasis 7-12. For instance, acid loading in rats increases urine phosphorus, presumably to augment titratable acid excretion 11. However, study conclusions differ about whether this phenomenon is the result of indirect effects of the phosphaturic hormones PTH and FGF-23 8,9,12, or direct effects on sodium-phosphate transporters 7,11. Furthermore, in studies documenting increased PTH and FGF-23 transcription, the pH used to elicit these changes was below the typical systemic pH of patients with early to moderate CKD 8,12. Thus, few studies in animals or humans have evaluated integrated acid-base and phosphorus physiology relevant to early or moderate CKD when overt metabolic acidosis is uncommon, but adaptations to increase titratable acidity may already be occurring 7,13. Due to well-documented risks associated with even minor changes in FGF-23 and other aspects of mineral metabolism 14, acidosis and acid load may represent additional targets to prevent early derangements in the phosphorus axis. In this study, we used comprehensive data from a prospective cohort of patients with CKD to test the hypothesis that acid load and acidosis are associated with phosphorus homeostasis and phosphaturic hormones.

Methods

Study Population

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study is an observational cohort study of 3939 individuals with CKD recruited in 2003-2008 at multiple centers in the United States. All participants were aged 21-74 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) within 20-70 ml/min/1.73 m2 at enrollment. By design, approximately 50% of participants had diabetes mellitus. Participants with multiple myeloma, polycystic kidney disease or requiring active immunosuppressive therapy were excluded. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously reported 15,16. The current report includes 980 CRIC participants who were randomly selected to have net acid excretion measurements performed in 24-hour urine collections from baseline (n=1000) and who had a urine pH of 4.0-7.4 (n=20 excluded). All participants provided written informed consent for participation in the CRIC Study. The CRIC Study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at all clinical centers and the net acid excretion ancillary study was deemed exempt by the Duke University Health System IRB under protocol number Pro00056642.

Measurements and Data Collection

We quantified acid load as net acid excretion and potential renal acid load (PRAL) and acidosis based on serum bicarbonate, each as exposure variables. Outcomes include urine and serum phosphorus, urine calcium, FGF-23, and PTH. Net acid excretion was calculated from urine ammonium, pH, phosphorus and creatinine (see end of paragraph). Other urine measurements were used as dietary biomarkers, such as urine urea nitrogen and urine sulfate, or outcome measurements (e.g., urine calcium and phosphorus). Urine ammonium, pH and sulfate were measured in baseline 24-hour urine collections that had been stored at -80°C since collection. Urine pH was measured by an electrode, urine ammonium was measured using enzymatic assays, and urine sulfate by turbidometric assay, each by Litholink Corp® (Chicago, IL). Other clinical urine variables (e.g., urine phosphorus, calcium, creatinine and urine nitrogen) were measured in the central CRIC laboratory in baseline 24-hour urine samples that had been stored at -20°C. Titratable acidity was calculated using the Henderson Hasselbalch equation, urine pH, phosphorus, and creatinine and the pKa values of the relevant reactions, as previously described by our group 13 and others 17-19. Net acid excretion was calculated as the sum of titratable acidity and urine ammonium, with urine bicarbonate assumed negligible in a urine pH range of 4.0 to 7.4 13.

Bicarbonate, phosphorus, intact PTH (Scantibodies, Santee, California) and carboxy-terminal FGF-23 (Immutopics, San Clemente, California) were measured in baseline serum samples at the CRIC central laboratory. Dietary intake was assessed using the National Cancer Institute Diet History Questionnaire20. The PRAL estimates the contribution of the diet to fixed acid production as follows: PRAL= 0.49 × protein (g) + 0.037 × P (mg) - 0.021 × K (mg) – 0.026 × Mg (mg) – 0.013 × Ca (mg) 21. PRAL was set to missing for individuals using alkali supplements (n=23).

Additional covariates were measured per CRIC protocol. Demographics and medical history were assessed by self-reported questionnaire. History of cardiovascular disease was defined as self-reported history of congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, prior myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization. History of diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl, random glucose ≥200 mg/dl or use of diabetic medications including insulin or hypoglycemic medications each at the baseline study visit. A history of smoking was defined as lifetime use of ≥100 cigarettes. Body composition including body mass index (BMI) was assessed by anthropometry. Kidney function was measured as eGFR using the CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation; and albuminuria quantified as total albumin excretion in a 24 hour urine collection. Per the CRIC protocol, measured iothalamate glomerular filtration rate (iGFR) was performed by urine clearance in 1/3 of the cohort 16,22.

Statistical Analysis

We examined baseline characteristics of study participants by categories of serum bicarbonate. Characteristics according to quartiles of net acid excretion have been previously reported 13. We modeled the associations between acid-base parameters (net acid excretion, PRAL and serum bicarbonate) and the expected mean outcome level (urine and serum phosphorus, urine calcium, FGF-23, PTH) using generalized linear models. All models adjusted sequentially for demographics (age, sex, black versus nonblack race), kidney function (eGFR and 24-hour urine albumin), comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and ever versus never smoking), BMI, diuretic use and 24 hour urine creatinine. Urine calcium, FGF-23 and PTH were log-transformed prior to modeling due to skewed distributions. Thus, results for these outcome variables are reported as percent difference in the geometric mean. All models incorporate robust variance estimation due to heteroscedastic residuals noted during model checking for some outcomes. Adjusted quantile regression was used to model the median of untransformed FGF-23, PTH and urine calcium as an alternative methodology 23. Confidence intervals (CIs) for these models were calculated by bootstrapping with 1000 replicates.

We performed several secondary, sensitivity and subgroup analyses to ensure robust results. First, because FGF-23 and PTH modulate phosphorus homeostasis in part by altering the fractional excretion of phosphorus (FEPi), we evaluated FEPi as a secondary outcome. FEPi was calculated as (urine phosphorus* serum creatinine)/(serum phosphorus * urine creatinine) * 100. FEPi >100% were excluded from the analysis (n=6). Second, because urine phosphorus is used in calculation of the titratable acid component of net acid excretion, we also performed sensitivity analyses evaluating associations of independently measured components of acid excretion (i.e., urine ammonium and urine pH) with urine phosphorus. Third, urine phosphorus, serum phosphorus and acidification parameters may each be influenced by nutrition; thus, we performed analyses additionally adjusted for nutrition parameters including total energy intake and dietary phosphorus, as well as urine urea nitrogen and urine sulfate as unbiased measures of protein intake. Finally, net acid excretion, serum bicarbonate and mineral metabolites can be affected by kidney function. We evaluated each relationship adjusted for directly measured (using iothalamate clearance) GFR where available (n=359). As secondary analyses, we performed models stratified by sex, level of eGFR, BMI, diuretic use, and history of diabetes. All analyses were performed using Stata SE version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Participants and Overview

Overall, the study population included 57% males and 51% of the participants had diabetes. Mean eGFR was 44.0 ± 14.4 mL/min/1.73 m2; mean net acid excretion was 33 ±18 mEq/d. Mean PRAL was -3.4 ± 20.0 mEq/day. Eighteen % of the study population had a serum bicarbonate < 22 mEq/L. Several acid-base exposure measures were modestly to moderately correlated (see Table S1). Lower serum bicarbonate was associated with greater likelihood of diabetes, lower eGFR, greater albuminuria, as well as lower urine pH, potassium and creatinine (Table 1). Clinical characteristics according to quartiles of net acid excretion have been previously published and are notable for associations of higher net acid excretion with higher eGFR, greater total energy intake and larger body size, among other characteristics 13.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population according to serum bicarbonate.

| Serum Bicarbonate | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥22 mEq/L (n=793)† | <22 mEq/L (n=178) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 58 ±11 | 58 ±11 | 0.7 |

| Male sex | 56.6% | 57.3% | 0.9 |

| Black race | 44.1% | 38.2% | 0.1 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 48.3% | 61.2% | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 85.4% | 89.9% | 0.1 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 31.9% | 32.6% | 0.9 |

| Ever smoker | 55.9% | 56.2% | 0.9 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Urine pH | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| 24 h urine ammonium (mmol/d) | 13 (8, 20) | 12 (8, 20) | 0.4 |

| 24 h urine creatinine (g/d) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.03 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 46 ± 15 | 36 ±13 | <0.001 |

| 24 h urine albumin (mg/d) | 53 (9, 418) | 199 (24, 1314) | <0.001 |

| Physical Examination | |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 127 ± 22 | 129 ± 23 | 0.2 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 71 ± 12 | 70 ± 13 | 0.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32 ± 8 | 32 ± 7 | 0.3 |

| Medications | |||

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 68.0% | 74.6% | 0.09 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 4.7% | 5.1% | 0.8 |

| Diuretic | 58.9% | 57.6% | 0.8 |

| Anti-acidosis medications | 2.5% | 3.4% | 0.5 |

| Active Vitamin D | 2.3% | 3.4% | 0.4 |

| Phosphorus binder | 6.7% | 5.7% | 0.6 |

| Dietary Data | |||

| Total energy (kcal/d | 1669 (1200, 2259) | 1539 (1098, 2282) | 0.3 |

| Calories from protein (%) | 16 ± 4 | 16 ± 4 | 0.6 |

| Calories from fat (%) | 34 ± 8 | 35 ± 9 | 0.04 |

| Calories from carbohydrates (%) | 51 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | 0.09 |

| Phosphorus (mg/d) | 1048 (757, 1458) | 1045 (676, 1367) | 0.5 |

| Calcium (mg/d) | 626 (436, 866) | 609 (391, 880) | 0.3 |

| Sodium (mg/d) | 2579 (1836, 3628) | 2583 (1665, 3476) | 0.6 |

| 24 h urine urea nitrogen (g/d) | 7.8 (5.7, 10.7) | 7.5 (5.2, 10.0) | 0.3 |

| 24 h urine potassium (mmol/d) ‡ | 51 (38, 69) | 44 (32, 65) | 0.003 |

| 24 h urine sodium (mmol/d) | 149 (108, 203) | 148 (103, 198) | 0.7 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as percentage; values for continuous variables, as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

serum bicarbonate was missing in 9 individuals

Urine and Serum Phosphorus

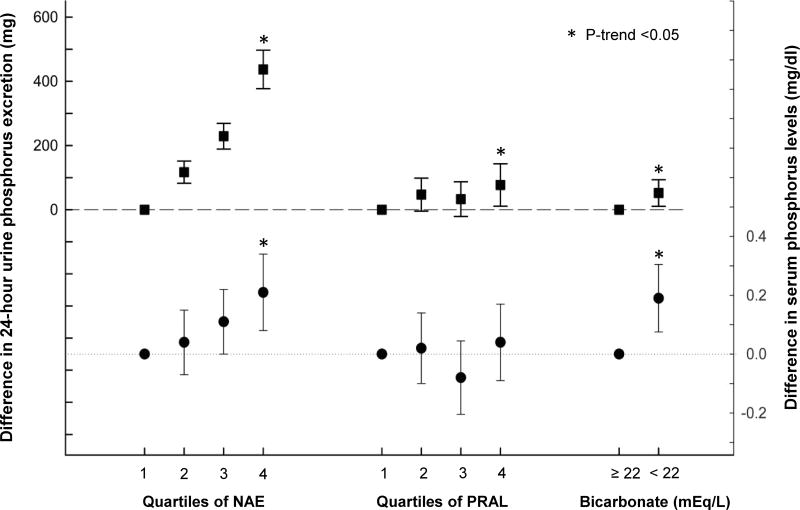

24 hour urine phosphorus was significantly higher among those with higher net acid excretion in demographic-adjusted models (p for trend <0.001) and after full adjustment (437 [95% CI, 377-497] mg higher in quartile 4 versus 1; Figure 1). Likewise, higher quartiles of PRAL were also associated with greater 24 hour urine phosphorus in demographic-adjusted models (p for trend=0.002) and fully adjusted models (77 [95% CI, 11-143] mg higher in quartile 4 versus 1; Figure 1). Lower serum bicarbonate was not associated with 24 hour urine phosphorus in unadjusted models; however, after full adjustment, 24 hour urine phosphorus was 52 (95% CI, 10-93) mg higher among those with a bicarbonate level <22 compared to ≥22 mEq/L. Associations between net acid excretion, PRAL, serum bicarbonate, and urine phosphorus were similar after additional adjustment for 25-hydroxyvitamin D or if excluding individuals using active vitamin D sterols.

Figure 1. Adjusted absolute difference in mean 24-hour urine phosphorus and serum phosphorus across quartiles of net acid excretion (NAE), quartiles of potential renal acid load (PRAL) and bicarbonate levels.

Squares represent the difference between 24 hour urine phosphorus levels and reference category. Circles represent the difference between serum phosphorus levels and reference category. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Models are adjusted for age, sex, black vs. non-black race, estimated GFR, 24h urine albumin, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, body mass index, diuretic use, and 24h urine creatinine. (*) indicates p-trend <0.05 from a continuous linear model.

Higher net acid excretion was also associated with higher serum phosphorus in fully adjusted models (0.21 [95% CI, 0.08-0.34] mg/dl higher serum phosphorus in quartile 4 versus 1 of net acid excretion; Figure 1). Serum phosphorus was not associated with PRAL, but was 0.19 (95% CI, 0.08-0.31) mg/dl higher among those with serum bicarbonate <22 versus ≥22 mEq/L after full adjustment (Figure 1).

Urine Calcium

Because urine phosphorus mobilization could be related to release from bone, urine calcium was also evaluated as an outcome measure. Similar to urine phosphorus, 24 hour urine calcium was significantly higher in higher quartiles of net acid excretion after full adjustment (66% [95% CI, 35%-107%] higher in quartile 4 versus 1). PRAL was not significantly associated with urine calcium after adjustment (p=0.1). 24-hour calcium was significantly lower in patients with low serum bicarbonate in models adjusted for demographics, kidney function and comorbidities (-17% [95% CI, -29% to -2%] among those with serum bicarbonate <22 versus ≥22 mEq/L), but this association mildly attenuated and was not significant after additional adjustment for BMI, diuretic use and 24 hour urine creatinine (-14%; 95% CI, -26% to 0%).

Phosphaturic Hormones

In a demographic adjusted model, FGF-23 trended lower across increasing quartiles of net acid excretion, but this association attenuated after adjustment for eGFR (Table 2). Likewise, FGF-23 levels were 36% (95% CI, 21%-53%) higher in participants with a serum bicarbonate <22 mEq/L in the demographic adjusted model, but these trends attenuated in the fully adjusted model (p=0.2). The PRAL was not associated with levels of FGF-23 in any model (Table 2).

Table 2. Relative difference in geometric mean of PTH and FGF-23 in demographic and fully adjusted models according to quartiles of net acid excretion, quartiles of PRAL, and serum bicarbonate.

| Net acid excretion | PRAL | Bicarbonate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p* | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p* | <22 mEq/L | p | |

| % Difference in PTH | ||||||||||

| Demographi c adjusted | -2 (-14, 12) | -3 (-15, 10) | -14 (-25, -3) | 0.01 | 0 (-13, 16) | 3 (-10, 18) | 3 (-11, 20) | 0.7 | 57 (39, 76) | <0.00 1 |

| Fully adjusted | 0 (-11, 12) | -1 (-11, 11) | -3 (-16, 11) | 0.6 | 3 (-8, 16) | 3 (-9, 16) | 6 (-6, 21) | 0.7 | 26 (13, 40) | <0.00 1 |

| % Difference in FGF-23 | ||||||||||

| Demographi c adjusted | -7 (-19, 7) | -11 (-22, 2) | -20 (-30, -8) | 0.00 2 | -12 (-25, 3) | -10(-21, 5) | -4 (-18, 13) | 0.4 | 36 (21, 53) | <0.00 1 |

| Fully adjusted | -2 (-13, 10) | -3 (-14, 9) | -4 (-16, 10) | 0.9 | -8 (-20, 5) | -9 (-19, 2) | -1 (-14, 13) | 0.8 | 7 (-3, 18) | 0.2 |

Note: Values are given as difference (95% confidence interval). For net acid excretion and PRAL quartiles, Q1 is reference category; for bicarbonate, ≥22 mEq/L is reference category. Demographic adjusted models are adjusted for age, sex, and black vs non-black race. Fully adjusted models are adjusted for demographics as well as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 24-h urine albumin, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, body mass index, diuretic use, and 24-h urine creatinine

FGF, fibroblast growth factor; PRAL, potential renal acid load; PTH, parathyroid hormone; Q, quartile; Ref, reference;

p is for linear trend from continuous model

Similar to FGF-23, PTH was lower with increasing quartiles of net acid excretion in a demographic adjusted model. No association was found between PTH and net acid excretion in a fully adjusted model or between PTH and PRAL in any model (Table 2). Levels of PTH were significantly higher when serum bicarbonate was <22 mEq/L with levels 57% (95% CI, 39%-76%) higher in a demographic adjusted model. The association remained significant in a fully adjusted model with a level 26% (95% CI, 13%-40%) higher among participants with bicarbonate <22 mEq/L.

Secondary, Sensitivity, and Subgroup Analyses

Both FGF-23 and PTH increase the FEPi to maintain phosphorus homeostasis. In secondary analyses, we evaluated the associations of net acid excretion, PRAL and serum bicarbonate with FEPi. Higher quartiles of net acid excretion, but not PRAL or serum bicarbonate < 22 mEq/L (p=0.9 for each), were associated with higher FEPi (absolute difference of 14% [95% CI, 12%-16%] between quartile 4 versus 1) in fully adjusted models (Figure S2).

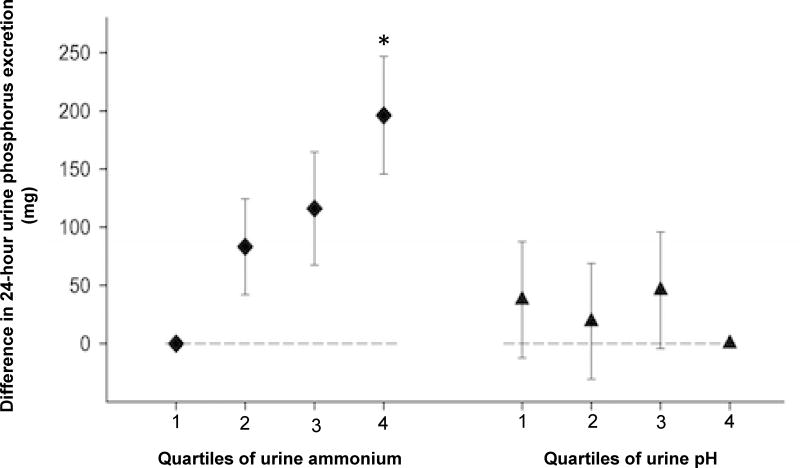

Urine phosphorus is a component of the net acid excretion calculation and, thus, these variables may be statistically correlated regardless of their biological relationships. Therefore, in addition to our complementary analyses of PRAL, we utilized urine ammonium and urine pH as alternative indices of acid excretion and modeled their fully adjusted association with 24 hour urine phosphorus and FEPi in sensitivity analyses. Among those with higher urine ammonium, 24 hour urine phosphorus remained higher, similar to in our primary models, although the magnitude of association was reduced (Figure 2). Lower urine pH did not associate with urine phosphorus (p for trend=0.2). Higher FEPi also remained associated with higher urine ammonium (absolute difference of 7.4% between quartile 4 versus 1 of urine ammonium; p<0.001).

Figure 2. Adjusted absolute difference in mean 24-hour urine phosphorus across quartiles of urine pH and urine ammonium.

Diamonds represent the difference between 24-hour urine phosphorus levels and reference category (quartile 1) across urine ammonium quartiles. Triangles represent the difference between 24-hour urine phosphorus levels and reference category (quartile 4) across urine pH quartiles. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Models are adjusted for age, sex, black vs. non-black race, estimated GFR, 24h urine albumin, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, body mass index, diuretic use, and 24h urine creatinine. (*) indicates p-trend <0.05 from a continuous linear model.

Dietary intake could affect both acid-base status as well as serum and urine phosphorus. We found similar associations of acid load and acidosis with urine and serum phosphorus when additionally adjusted for total energy intake, dietary phosphorus, urine urea nitrogen, or urine sulfate (figure a of Item S1). Kidney function is a critical potential confounder of associations between net acid excretion, serum bicarbonate and mineral metabolites. We found overall similar results when we adjusted analyses for measured GFR in a subset of participants (n=359; figure b of Item S1). Additional models stratified by clinical covariates were used to evaluate possible effect modification by eGFR, sex, BMI, diuretic use and history of diabetes. There was no evidence of moderation by any of these covariates (figures b-f of Item S1). Finally, quantile regression, which models median values of untransformed FGF-23, PTH and urine calcium, yielded similar inferences as primary results from log-linear models (Table S2).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 980 individuals with CKD, we observed that a higher acid load, and each of its components, namely higher net acid excretion, higher PRAL and, lower serum bicarbonate, were associated with higher 24-hour urine phosphorus excretion. Furthermore, both higher net acid excretion and lower serum bicarbonate also independently associated with higher serum phosphorus level. Although these results suggest phosphorus mobilization may help promote titratable acid excretion, the cross sectional nature of our study does not allow us to infer causality between our exposures and outcomes. Furthermore, limitations of our data do not allow us to evaluate whether higher circulating and urine phosphorus could reflect increased intestinal phosphorus absorption, or mobilization of phosphorus from sites of sequestration, such as bone or the intracellular space. We also cannot definitively exclude residual confounding by kidney function or nutrition as factors in these associations although several sensitivity analyses were robust to these factors. Despite these acknowledged limitations, ours is one of few studies evaluating the combined physiology of altered acid-base and phosphorus homeostasis in a CKD cohort. Based on our results, we hypothesize that higher acid load and acidosis may stimulate phosphate excretion in CKD in part by increasing the availability of circulating phosphorus and the filtered phosphorus load.

Prior studies documented increased urine phosphorus excretion in response to an acid load in healthy individuals and animal models 11,24. Many studies find evidence of bone demineralization 25-28 and increased calciuria 24,29,30 in the setting of an acid load. Similarly, in our study, urine calcium excretion was higher with higher acid load, suggesting bone as a potential source for the increased excretion of phosphorus. Other studies indirectly implicate mobilization of phosphorus from intracellular stores 31, or upregulation of intestinal phosphate absorption 10. However, in these prior studies of healthy individuals, acid-induced phosphaturia results in lower serum phosphorus, presumably due to renal losses that exceed absorbed or mobilized phosphorus 24. On the contrary, in our study, we observed that higher acid load and lower serum bicarbonate associated with higher, not lower, serum phosphorus. It is possible that in CKD, the limited ability to filter, and thus excrete, a phosphorus load could result in a different balance between acid-induced phosphorus mobilization and excretion that favors higher circulating phosphorus, yielding our results. With growing epidemiologic and pre-clinical evidence of risk associated with higher serum phosphorus in CKD 14, ongoing interventions to reduce acid load should be tested for impact on serum phosphorus, phosphorus absorption and mobilization from storage sites.

Somewhat surprisingly, although high net acid excretion did associate with higher FEPi, it was not associated with increased levels of phosphaturic hormones. Prior in vitro and in vivo studies conflict in this regard. In some studies, acidosis induced expression of the phosphaturic hormones FGF-23 12 and PTH 8,9,32,33, while altering expression and abundance of sodium phosphorus co-transporters in the proximal tubule 11. Other studies have attributed changes in phosphaturia to direct effects of pH on the flux through these co-transporters, but not their abundance 5, which is more consistent with our results. Although we did not observe an association between urine pH and urine phosphorus, final urine pH may not accurately reflect the local pH in the proximal tubule and thus local pH may be a factor driving differences in excretion. Our results related to phosphaturic hormones disagree with some prior studies of physiology. This may be related to the severity of acidosis in patients with early to moderate CKD 34. For instance, prior in vitro studies that documented increased FGF-23 transcription in acidic environments used experimental pH of 7.1–7.2 12, which is lower than would be expected in early to moderate CKD. However, we did find associations of low serum bicarbonate with higher PTH in our study.

Our study has many strengths, including detailed clinical phenotyping, direct dietary reporting and measurement of multiple parameters of acidification and mineral metabolism in a relatively large CKD cohort. However, several limitations affect our conclusions. This study is observational and cross-sectional. Although our results suggest possible links between acid-base and mineral metabolism, they cannot prove cause and effect. We evaluated 15 exposure-outcome relationships which can inflate study-wide type 1 error. However, p-values for many of our findings were strong and would have persisted below a more conservative Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.003. Additionally, limitations of our measurements include lack of blood pH measurements, estimates derived from dietary questionnaires that may be subject to recall biases (i.e., PRAL), use of urine samples reflecting a single day of exposure (i.e., net acid excretion) and the age of the stored urine samples that could affect testing accuracy 13. Overall, these measurement errors would typically increase variability and result in false negative, as opposed to false positive, findings.

In our study, general inferences regarding acid load were similar if quantified as net acid excretion, PRAL, or urine ammonium. This is critical because incorporation of urine phosphorus in the calculation of titratable acidity induces mathematical correlation between these variables. Additionally, the dependence of both relative over- and under-collection could induce some correlation between even biologically unrelated variables from timed urine collections. The latter concern was mitigated by adjustment for urine creatinine as a marker of collection adequacy. Although urine ammonium remained associated with urine phosphorus in our sensitivity analyses, urine pH did not. This may be because the higher quantity of urine buffer allows for greater titratable acid excretion without a more dramatic reduction in pH.

Finally, residual confounding by kidney function could contribute to some of the associations between acid-base and phosphorus parameters. It is unlikely to contribute to the direct associations observed between net acid excretion and serum phosphorus or indirect associations between serum bicarbonate and urine phosphorus, because the direction of expected confounding differs from the associations that we observed. For instance, at lower GFR, net acid excretion declines while serum phosphorus levels rise. However, in our results, these variables correlated directly, such that higher net acid excretion correlated with higher serum phosphorus levels. On the contrary, residual confounding by kidney function could theoretically induce spurious associations between net acid excretion, urine ammonium and urine phosphorus, each of which fall with lower kidney function 13,35. We have carefully performed sensitivity analyses using measured GFR where available to mitigate this concern.

Finally, diet could link the physiology of both acid-base and phosphorus homeostasis with higher protein intake contributing to both higher acid load and higher phosphorus content 36,37. We adjusted for a wide variety of dietary variables, where available, including estimated dietary phosphorus, total energy intake, urine sulfate and urine urea nitrogen with similar results. Interventional studies with alkali supplements or phosphorus binders will be better able to dissociate dietary phosphorus absorption and acid load to study direct effects of isolated changes.

Recently, both acid-base and mineral homeostasis have garnered attention as possible modifiable risk factors for progression and complications of CKD 14,38-41. Our results suggest physiologic links between these CKD complications that exceed their shared dependence on GFR and diet. Although this paradigm provides a rationale to evaluate for therapeutic synergy when treating both acid-base and mineral metabolism complications in CKD, trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Unadjusted correlation of acid-base exposure measurements.

Table S2: Difference in median PTH, FGF-23, and urine calcium in fully adjusted models by quartiles of net acid excretion, PRAL, and serum bicarbonate.

Figure S1: Conceptual model demonstrating hypothesized relationships.

Figure S2: Adjusted difference in fractional excretion of phosphorus by acid load.

Item S1: Selected results adjusted for nutrition indicators, eGFR, sex, diuretic use, BMI, and history of diabetes.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi: _______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Acknowledgments

The CRIC Study Investigators include Lawrence J. Appel, MD, MPH, Harold I. Feldman, MD, MSCE, Alan S. Go, MD, Jiang He, MD, PhD, John W. Kusek, PhD, James P. Lash, MD, Akinlolu Ojo, MD, PhD, Mahboob Rahman, MD, and Raymond R. Townsend, MD.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of CRIC participants and staff.

Support: This study was supported in part by grant K23DK095949 (to Dr Scialla) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Dr Khairallah was supported in part by a Stead Resident Research Award from the Duke University Department of Medicine. Dr Isakova was supported by grant R01DK110087 from the NIDDK. A statistical consultation was obtained from Huiman Barnhart, PhD through the Duke O'Brien Center for Kidney Disease Research (P30DK096493). Funding for the CRIC Study was obtained under a cooperative agreement from the NIDDK (U01DK060990, U01DK060984, U01DK061022, U01DK061021, U01DK061028, U01DK060980, U01DK060963, and U01DK060902). In addition, this work was supported in part by: the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Clinical and Translational Science Award NIH [National Institutes of Health]/NCATS [National Center or Advancing Translational Sciences] UL1TR000003, Johns Hopkins University UL1 TR-000424, University of Maryland General Clinical Research Center M01 RR-16500, Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the NCATS component of the NIH and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research UL1TR000433, University of Illinois at Chicago Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1RR029879, Tulane Center of Biomedical Research Ethics for Clinical and Translational Research in Cardiometabolic Diseases P20 GM109036, Kaiser Permanente NIH/National Center for Research Resources University of California San Francisco-Clinical and Translational Science Institute UL1 RR-024131. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. The funders had no direct role in study design, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr Isakova has received consulting fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin. The other authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: PK, TI, JA, HF, MW, J; data acquisition: TI, JA, LH, MR, ML, EM, BJ, CB, HF, MW, JJS; data analysis/interpretation: PK, TI, JA, LH, MD, MR, KS, ML, HF, MW, JJS; statistical analysis: PK, WY, XW, JJS; supervision or mentorship: HF, MW, JJS. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Peer Review: Evaluated by 4 external peer reviewers, a statistician, and an Acting Editor-in-Chief.

N Section (2×): In line with AJKD's procedures for potential conflicts of interest for editors, described in the Information for Authors & Journal policies, Editorial Board Member Masafumi Fukagawa, MD, PhD, served as Acting Editor-in-Chief and handled the peer-review and decision-making processes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Relman AS, Lennon EJ, Lemann J., Jr Endogenous production of fixed acid and the measurement of the net balance of acid in normal subjects. J Clin Invest. 1961;40:1621–1630. doi: 10.1172/JCI104384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remer T. Influence of diet on acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000;13(4):221–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2000.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M. Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1257–1272. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09750913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiess WA, Ayer JL, Lotspeich WD, Pitts RF, Miner P. The renal regulation of acid-base balance in man II: Factors affecting the excretion of titratable acid by the normal human subject. J Clin Invest. 1948;27(1):57–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI101924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowik M, Picard N, Stange G, et al. Renal phosphaturia during metabolic acidosis revisited: molecular mechanisms for decreased renal phosphate reabsorption. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457(2):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamm LL, Simon EE. Roles and mechanisms of urinary buffer excretion. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(4 Pt 2):F595–605. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.4.F595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burki R, Mohebbi N, Bettoni C, Wang X, Serra AL, Wagner CA. Impaired expression of key molecules of ammoniagenesis underlies renal acidosis in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(5):770–781. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campion KL, McCormick WD, Warwicker J, et al. Pathophysiologic Changes in Extracellular pH Modulate Parathyroid Calcium-Sensing Receptor Activity and Secretion via a Histidine-Independent Mechanism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(9):2163–2171. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disthabanchong S, Martin KJ, McConkey CL, Gonzalez EA. Metabolic acidosis up-regulates PTH/PTHrP receptors in UMR 106-01 osteoblast-like cells. Kidney Int. 2002;62(4):1171–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stauber A, Radanovic T, Stange G, Murer H, Wagner CA, Biber J. Regulation of intestinal phosphate transport. II. Metabolic acidosis stimulates Na(+)-dependent phosphate absorption and expression of the Na(+)-P(i) cotransporter NaPi-IIb in small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288(3):G501–506. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00168.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambuhl PM, Zajicek HK, Wang H, Puttaparthi K, Levi M. Regulation of renal phosphate transport by acute and chronic metabolic acidosis in the rat. Kidney Int. 1998;53(5):1288–1298. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger NS, Culbertson CD, Kyker-Snowman K, Bushinsky DA. Metabolic acidosis increases fibroblast growth factor 23 in neonatal mouse bone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303(3):F431–436. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00199.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scialla JJ, Asplin J, Dobre M, et al. Higher net acid excretion is associated with a lower risk of kidney disease progression in patients with diabetes. Kidney Int. 2017;91(1):204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scialla JJ, Wolf M. Roles of phosphate and fibroblast growth factor 23 in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(5):268–278. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LJ, et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(8):1302–1311. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, et al. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design and Methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S148–153. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070149.78399.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lennon EJ, Lemann J, Jr, Litzow JR. The effects of diet and stool composition on the net external acid balance of normal subjects. J Clin Invest. 1966;45(10):1601–1607. doi: 10.1172/JCI105466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitts RF, Alexander RS. The nature of the renal tubular mechanism for acidifying the urine. Am J Physiol. 1945;144(2):239–254. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ring T, Nielsen S. Whole-body acid-base modeling revisited. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00560.2016. ajprenal 00560 02016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires : the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remer T. Influence of diet on acid-base balance. Semin Dial. 2000;13(4):221–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2000.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denker M, Boyle S, Anderson AH, et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study (CRIC): Overview and Summary of Selected Findings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(11):2073–2083. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04260415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu K, Lu Z, J S. Quantile regression: applications and current research areas. The Statistician. 2003;52(3):331–350. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krapf R, Vetsch R, Vetsch W, Hulter HN. Chronic metabolic acidosis increases the serum concentration of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in humans by stimulating its production rate. Critical role of acidosis-induced renal hypophosphatemia. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(6):2456–2463. doi: 10.1172/JCI116137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushinsky DA, Chabala JM, Gavrilov KL, Levi-Setti R. Effects of in vivo metabolic acidosis on midcortical bone ion composition. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(5 Pt 2):F813–819. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.5.F813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck N, Webster SK. Effects of acute metabolic acidosis on parathyroid hormone action and calcium mobilization. Am J Physiol. 1976;230(1):127–131. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bushinsky DA. Net calcium efflux from live bone during chronic metabolic, but not respiratory, acidosis. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(5 Pt 2):F836–842. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.5.F836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bushinsky DA, Frick KK. The effects of acid on bone. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2000;9(4):369–379. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bleich HL, Moore MJ, Lemann J, Jr, Adams ND, Gray RW. Urinary calcium excretion in human beings. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(10):535–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197909063011008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barone S, Amlal H, Xu J, Soleimani M. Deletion of the Cl-/HCO3- exchanger pendrin downregulates calcium-absorbing proteins in the kidney and causes calcium wasting. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(4):1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemann J, Jr, Litzow JR, Lennon EJ. The effects of chronic acid loads in normal man: further evidence for the participation of bone mineral in the defense against chronic metabolic acidosis. J Clin Invest. 1966;45(10):1608–1614. doi: 10.1172/JCI105467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bushinsky DA, Nilsson EL. Additive effects of acidosis and parathyroid hormone on mouse osteoblastic and osteoclastic function. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(6 Pt 1):C1364–1370. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez I, Aguilera-Tejero E, Felsenfeld AJ, Estepa JC, Rodriguez M. Direct effect of acute metabolic and respiratory acidosis on parathyroid hormone secretion in the dog. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(9):1691–1700. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Metabolic Acidosis of CKD: An Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(2):307–317. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79(12):1370–1378. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scialla JJ, Anderson CA. Dietary acid load: a novel nutritional target in chronic kidney disease? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(2):141–149. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, et al. Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1511–1518. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobre M, Rahman M, Hostetter TH. Current status of bicarbonate in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(3):515–523. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Brito-Ashurst I, Varagunam M, Raftery MJ, Yaqoob MM. Bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):2075–2084. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE. Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2014;86(5):1031–1038. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahajan A, Simoni J, Sheather SJ, Broglio KR, Rajab MH, Wesson DE. Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2010;78(3):303–309. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Unadjusted correlation of acid-base exposure measurements.

Table S2: Difference in median PTH, FGF-23, and urine calcium in fully adjusted models by quartiles of net acid excretion, PRAL, and serum bicarbonate.

Figure S1: Conceptual model demonstrating hypothesized relationships.

Figure S2: Adjusted difference in fractional excretion of phosphorus by acid load.

Item S1: Selected results adjusted for nutrition indicators, eGFR, sex, diuretic use, BMI, and history of diabetes.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi: _______) is available at www.ajkd.org