Abstract

Prenatal stress (PS) has complex neurological, behavioural and physiological consequences for the developing offspring. The phenotype linked to PS usually lasts into adulthood and may even propagate to subsequent generations. The often uncontrollable exposure to maternal stress and the lasting consequences emphasize the urgent need for treatment strategies that effectively reverse stress programming. Exposure to complex beneficial experiences, such as environmental enrichment (EE), is one of the most powerful therapies to promote neuroplasticity and behavioural performance at any time in life. A small number of studies have previously used EE to postnatally treat consequences of PS in the attempt to reverse deficits that were primarily induced in utero . This review discusses the available data on postnatal EE exposure in prenatally stressed individuals. The goal is to determine if EE is a suitable treatment option that reverses adverse consequences of stress programming and enhances stress resiliency. Moreover, this review discusses data with respect to relevant hypotheses including the cumulative stress and the mismatch hypotheses. The articles included in this review emphasize that EE reverses most behavioural, physiological and neural deficits associated with PS. Differing responses may be dependent on the timing and variability of stress and EE, exercise, and potentially vulnerable and resilient phenotypes of PS. Results from this study suggest that enrichment may provide an effective therapy for clinical populations suffering from the effects of PS or early life trauma.

Keywords: maternal stress, pregnancy, enriched environment, mismatch hypothesis, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, HPA axis, stress response, stress vulnerability, stress resilience

Introduction

Stress, in particular psychosocial stress, is experienced by more than 80% of pregnant women [ 1 ]. Prenatal stress (PS), induced by exposure to social, physical or environmental distress during pregnancy, may threaten the natural regulatory capacity of the endocrine, immune and nervous systems in the developing foetus [ 2 ]. A stressful situation experienced by the pregnant mother activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis to initiate the release of stress hormones, such as cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rats. The corticosteroids may enter the foetal circulation [ 3 ] and programme the offspring’s HPA axis activity and stress response in later life [ 4 , 5 ]. In addition, the effects of maternal stress can be passed on to the offspring through changes in maternal behaviour and maternal care [ 6 , 7 ] and through paternal effects of stress on maternal behaviour [ 8 ] and offspring development [ 9 ].

Epigenetic mechanisms take a pivotal role in the transmission of stress or other experiences from one generation to the next [ 10 , 11 ]. Epigenetics is usually defined as the study of heritable changes in gene expression that are not due to changes in DNA sequence. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate diverse biological properties of cells and tissues by altering gene expression, and they rapidly respond to environmental factors [ 12–14 ]. For example, stressing male rats during spermatogenesis generates epigenetic DNA methylation marks, which are passed on from the father to the offspring, leading to reduced stress reactivity and slower motor development [ 9 ]. In addition, the paternal stress altered DNA methylation patterns in offspring that was visible in adolescence. While programming by the PS may primarily have the purpose to better prepare the offspring for survival in adverse environmental conditions, the adaptive benefit may come at a physiological and metabolic expense, thus generating adverse health outcomes.

Adverse health outcomes linked to PS concern the endocrine and immune systems, with secondary health outcomes manifesting in the elevated risk of psychopathologies and neurological disease [ 15 ], reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes [ 16 , 17 ], along with a greater risk for hypertension and diabetes [ 18 ]. For example, PS, mainly through dysregulation of the HPA axis, may alter neurodevelopment and lead to altered dendritic morphology [ 19 ], and the susceptibility to affective and hyperactive behaviours ([ 20 ] for review on PS and brain development see [ 21 ]). These behavioural phenotypes have been shown to persist to future generations [ 16 , 22 ], with epigenetic transgenerational inheritance being a primary etiological factor [ 13 , 23 ]. Importantly, epigenetics is a reversible and malleable system, which can be influenced positively and negatively by environmental factors. Thus, based on the evidence that PS adversely effects health and is passed across multiple generations, treatments to prevent or reverse the detrimental effects of PS are of significant interest.

Environmental enrichment (EE) is a non-invasive therapy that produces robust changes in neuronal morphology and behaviour. In experimental studies, housing animals in an EE provides them with rich social, motor, cognitive and sensory stimulation. EE was first studied in the 1940s by the Canadian neuropsychologist Donald O. Hebb, who brought laboratory rats to his home, thus ‘enriching’ their environment. He noted that rats reared as pets in his house performed better on memory tasks compared with rats reared in standard laboratory conditions [ 24 ]. Further study by Hebb’s team found that laboratory dogs that were treated as pets are superior in problem-solving than those reared in simple or deprived environments [ 25 ]. In addition, the authors suggested that social behaviour and motivation improved in the enriched dogs [ 25 ].

Since Hebb’s first experiments, the combination of a multimodal stimulation in EE in animal studies has proved to produce many beneficial anatomical, molecular and behavioural changes. Neuroanatomical studies have shown an increase in cortical weight, thickness and an increase in dendritic organization in EE rats [ 26–28 ]. Molecular studies have shown that EE causes an increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is involved in hippocampal (HPC) neuroplasticity and cortex [ 29 ]. More recently, the epigenetic mechanisms of positive environments have also been a focus, to accompany the larger understanding of the mechanisms of adverse early life experiences. For example, one study has shown that enrichment causes a high degree of histone acetylation at the BDNF gene in adulthood [ 30 ], causing a larger expression of BDNF seen in previously mentioned studies. With these epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone modifications, DNA methylation and variations in microRNA expression, most likely acting as primary mechanisms, EE has been shown to effectively promote recovery from neurological disorders, such as stroke [ 31 , 32 ], traumatic brain and spinal cord injury [ 33 ] and exert protective effects in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease [ 34 , 35 ]. Notably, EE may have considerable translational value for preclinical studies. Enriching an environment has significant ecological validity for the human population and better reproduces the human lifestyle than a standard shoebox cage with pair housing.

EE strategies have also been successfully applied to the human population. Although enrichment in a complex human environment can hardly be standardized, a wealth of studies has shown that specific experiential treatments promote endocrine, neuronal and behavioural functions. Though different in their mechanisms, exposure to mindfulness meditation [ 36 ], music lessons [ 37 ] or physical activities [ 38 ] represent just a few examples of EE strategies that have been studied in humans.

Given the extensive use of EE in animal studies of brain plasticity, it is somewhat surprising that relatively few studies have applied this treatment to PS. Moreover, it is also surprising that that there is a lack of studies measuring epigenetic changes due to EE and its mitigation of the effects of PS. One reason for this lack of studies may be the expectation that EE is insufficient and inappropriate to address the drastic impact of PS. For example, the complex environment offered by EE encourages extensive physical exercise, which may elevate the stress response [ 39 ]. Furthermore, EE houses animals in larger groups compared with regular housing conditions in standard shoebox cages. The interaction in a large social setting may at times generate aversive behaviours, depending on the space provided [ 40 ]. Accordingly, EE has been reported to cause neuroendocrine repercussions that may be similar to those observed in chronic stress [ 41 ]. In addition, Larsson et al. [ 39 ] suggested that the rich physical and sensory stimulation generated by EE may represent a mild, recurring stressor due to the repeated introduction of novel objects.

Although EE is generally considered to be a beneficial treatment, there are some insinuations as to why EE may not be useful in treating offspring vulnerabilities after PS. Hypotheses including the cumulative stress and the mismatch hypothesis create concern over the appropriate postnatal environment for prenatally stressed individuals. The cumulative stress hypothesis states that aversive experiences in early life predispose individuals to be more vulnerable to aversive challenges later in life [ 42 ]. In this hypothesis, cumulative or chronic stress causes an individual to be unable to cope with stressors and as a result, the wear and tear of stress takes a toll on health. Here, one could expect that EE would have a beneficial effect, essentially reversing the adverse health outcomes caused by PS. On the other hand, the mismatch hypothesis states that aversive experiences early in life trigger adaptive processes, which render an individual to be better adapted to aversive challenges in later life [ 42–44 ]. If this hypothesis proves correct, one would expect that prenatally stressed offspring, who are essentially being prepared for survival in a stressful environment, would not benefit from being placed in an EE.

Due to these varying hypotheses, a review of the current findings on PS and EE was conducted to determine if EE is a suitable treatment option to reverse the adaptive or detrimental effects of PS that were induced in utero . This review will summarize the current literature addressing the effectiveness of postnatal EE to treat adverse outcomes associated with PS. Specifically, the review will focus on the question of whether deficits due to PS can be reversed through exposure to EE in later life with the goal of supplying an overview of the current literature in the field.

Results

Forms of PS and EE

A variety of techniques can be used to induce PS in animal models. The studies that investigated EE used prenatal stressors that ranged from maternal social and psychological stress (i.e. predator stress and social isolation) to physical stress (i.e. foot shock, restraint and swim stress). In addition to these stressor types, the time at which the stressor was given [gestational day (G) 12–18 or G13–15], the duration of the stressor (between 3 and 6 h, every day or every other day), the order of stressors (if more than one, random or non-random) and the time of day at which the stressors were given, differed as well. These stressors are meant to cause physiological stress, due to their unpredictable and uncontrollable nature. When using animal models of stress along with enrichment, the stress protocols are important as many stressors (those that are controllable and predictable) may not generate chronic physiological stress, but rather resilience or adaptation [ 45 ]. These factors all contribute to the overall effect size and severity of PS in animals [ 21 ] and influence the efficacy of EE therapy.

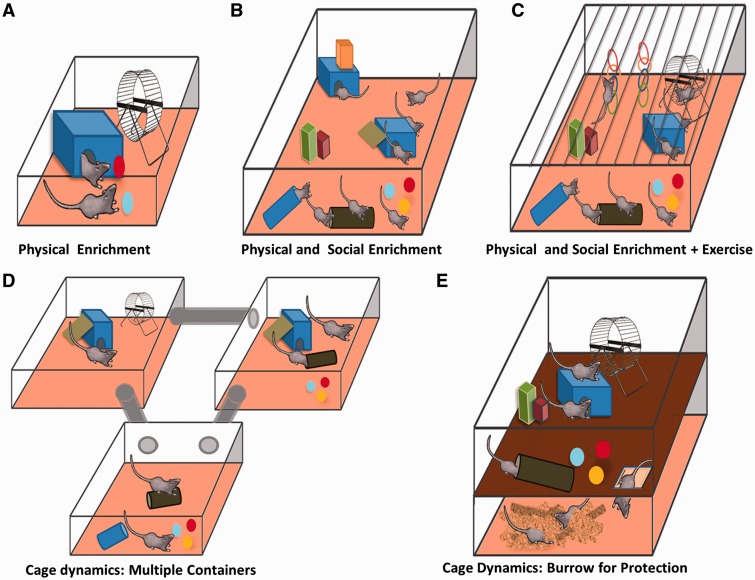

Along with stressor variability, postnatal enrichment paradigms also differed vastly amongst the included studies. In general, there are two categories of enrichment in the literature included in this review: physical enrichment and physical plus social enrichment. Physical enrichment is defined as enrichment using physical or sensory stimuli to enrich the environment. This type of enrichment may include toys, elevated platforms, exercise wheels and novel objects that change on a regular basis. Social enrichment involves the housing of multiple animals in one large condominium in order to promote social interactions and play. These categories are further divided into the cage dynamics (size of cage, platform levels etc.) as shown in Fig. 1 . Other manipulations to the environment not shown in the illustrations include novel food, various materials for bedding, sand or other material for somatosensory stimulation, the time spent in the EE and the frequency of introducing novel items (every day, once a week etc.). Also, in some cases, food was frequently moved to different locations to encourage foraging and explorative behaviour. For translational purposes, it should be also noted that the EE in animal models may only be simulating standard human conditions, whereas standard animal cages may be considered as an impoverished human condition. This is important to note in all experimental animal studies, but is especially critical when manipulating the environment. All experiments included in this review had control groups of two to four animals per cage (with the exception of three articles which did not specify their control housing conditions), which is noteworthy because the housing of several animals together mitigates a rather impoverished state (seen when animals are housed alone).

Figure 1:

Schematic overview of types of enriched environments. This illustration depicts the variability in enrichment paradigms used across studies, including variation in the physical and sensorimotor components and the social dynamics.

Reversibility of PS with enriched environment

The effects of PS and the impact of EE in the respective animal models of PS were recorded for three categories: behavioural, morphological and molecular. A summary of the effects of PS and EE is provided in the following sections.

Influence of EE on behavioural outcomes induced by PS

Fourteen of the 15 studies reported behavioural outcomes of PS and EE. Many behavioural paradigms were used to measure changes in affective disorders, fear, addiction, learning and memory, and motor abilities. The particular behavioural changes are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1:

Summary of the behavioural measurements and outcomes of prenatal stress and environmental enrichment

| Reference | Prenatal stressor | Type of EE | Animals | Measures | Behavioural outcomes of PS | Behavioural outcomes of PS + EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emack and Matthews [ 51 ] |

G32–G66 1 of 4 stressors every second day

|

n = 6–10, P25 Physical enrichment and social enrichment | Guinea Pigs ♂ and ♀ P35, P50, P70 |

|

Male: PS elevated locomotor activity, Prepulse inhibition: Females: PS decreased PPI | Females: decrease in locomotor activity Prepulse inhibition: Males: EE increased PPI in both control and PS offspring; Female offspring: both PS and EE decreased PPI |

| Koo et al. [ 52 ] | G4–5 to G20–21 Immobilization stress for 6 h/day | n = 10–12, P21 Physical enrichment and social enrichment exercise | SD rats ♂ P60, P90 |

|

PS impaired learning and memory performance | EE enhanced cognitive functions |

| Laviola et al. [ 46 ] | G11–G21 restraint and white light for 45 min 3×/day | n = 2, P22 Physical enrichment and exercise | SD rats ♂ P38–P43 |

|

PS reduced age-typical rough-and-tumble play PS increased emotionality | Increase in the amount of positive species-typical behaviour (i.e. rough-and-tumble play) and reduced emotionality |

| Li et al. [ 53 ] | G13–G19 restraint 3×/day at 45 min long | n = 4, P21–P34 Physical enrichment and social enrichment exercise | SD rats ♂ and ♀ P35 |

|

PS impaired learning and memory performance; PS displayed more anxiety-like behaviour | EE reduced anxiety-like behaviour in PS offspring; learning and memory was partially improved |

| Lui et al. [ 54 ] | G14–G21 restraint 6 h/day | n = 6–8, P22 Physical enrichment and social enrichment exercise | SD rats ♂ P22–P120 |

|

PS adult offspring showed cognitive deficit | EE improved cognition in PS–EE group |

| Morley-Fletcher et al. [ 77 ] | G11–G22 restraint and bright halogen light for 45 min 3×/day | n = 2, P22 Physical enrichment and exercise and suspended items | SD rats ♂ P22–P60 |

|

PS decreased social play | EE markedly increased social play in PS rats |

| Pascual et al. [ 47 ] | G14–G21 restraint stress for 45 min 3×/day | n = 6–8, P22 Physical enrichment and social enrichment exercise and suspended items (EE for 2 h/day) | CF-1 Mice ♂ P22-P52 or P82 |

|

At P82, PS increased anxiety-like behaviour | EE decreased anxiety-like behaviour caused by PS |

| Qian et al. [ 49 ] | G11–G21 bright light stress for 45 min 3×/day | n = 10, P21 Physical enrichment and social enrichment exercise and suspended items | Wistar rats ♂ P21–P60 |

|

Acute stress increase amount of fear in DWT | Acute stress had no effect on fear in DWT in EE animals |

| Ulupinar et al. [ 58 ] | G14–G21 restraint 3 h/day | n = 12, P21 Physical enrichment and social enrichment with multiple containers and extra exercise | Wistar rats ♂ and ♀ P49-P60 *no controls |

|

Males: PS positively affected reaching performance compared to EE animals | Males: EE negatively affected performance in the motor learning tests and reaching performance Females: EE positively affected reaching performance |

| Yang et al. [ 50 ] | G13–G19 10 foot-shocks (0.8 mA for 1 s, 2–3 min apart for 30 min/day | n = 10, P22 Physical and social enrichment with multiple containers and exercise | Wistar rats ♂ P22, P52 |

|

CPP: PS increased addictive behaviour (greater preference to morphine); Forced swim: PS caused higher depressive-like behaviour | CPP: EE counteracted PS-induced addictive behaviour changes; Forced swim: EE restored PS-elicited depressive-like reactivity in offspring |

| Yang et al. [ 55 ] | G13–G19 10 foot-shocks (0.8 mA for 1 s, 2–3 min apart for 30 min/day | n = 10, P22 Physical and social enrichment with multiple containers and exercise | Wistar rats ♂ P60 |

|

Water–maze: prenatal stress impaired the spatial learning task (longer latencies to escape) electrophysiology: PS impaired LTP and facilitated LTD | Water–maze: EE rescued spatial learning deficits; electrophysiology: EE treatment counteracted PS effect on LTP and LTD |

| Zhang et al. [ 56 ] | G13–G19 restraint 45 min 3×/day | Neonatal handling: P4–P10 (15 min/day) EE: n = 12, P11 Physical and social enrichment exercise and suspended items | SD rats ♂ P10, P20, P45 (MWM at P45) |

|

PS impaired the spatial learning and memory ability | EE with neonatal handling promoted the spatial learning memory ability of PS rats |

| Zhang et al. [ 57 ] | G13–G19 restraint 45 min 3×/day | n = 12, P10 Physical and social enrichment exercise and suspended items | SD rats ♂ P15, P30, P50 |

|

PS impaired spatial learning and memory | EE enhanced spatial learning and memory compared to controls and PS group |

| Zubedat et al. [ 48 ] | G13–G15 G13: swim stress (5 min) G14: Mirror stress (5 min) G15: restraint stress: 3 × 30 min | n = 8, P30 Physical and social enrichment with exercise (added sandbox in order to diversify the cage texture, enriched diet) | Wistar rats ♂ P95 |

|

PS had an anxiogenic effect; PS increased startle response and immobility in startle reflex test; PS group showed superior performance in a motor learning task; PS impaired selective attention (ORT) as well as partial sustained attention (PPI) | EE had an anxiolytic effect; EE decreased startle response and immobility in startle reflex test; EE increased both PPI and ORT performance; EE group showed superior performance in the motor learning task |

Affective disorders, fear and addiction

Anxiety-like behaviours were measured using open field, elevated plus maze, Y-maze, social behaviour test and the defensive withdrawal task. In all cases, PS had an anxiogenic effect [ 46–48 ], with increased emotionality, as indicated by elevated locomotor activity, increased time spent in closed arms and reduced frequency of age-typical rough and tumble play ( Table 1 ). EE had an anxiolytic effect and lowered emotionality. PS was found to increase depressive-like behaviour as measured using the forced swim task which was restored with EE ( Table 1 ). Moreover, the amount of fear, as measured by the defensive withdrawal task after acute stress was increased in PS rats whereas animals placed in an EE showed no effect [ 49 ]. Lastly, addiction and attention was measured using prepulse inhibition (PPI), object recognition task (ORT) and conditioned place preference (CPP). PS increased addictive behaviour in terms of greater preference for morphine [ 50 ] and impaired selective attention as measured by ORT and impaired partial sustained attention as measured by PPI [ 48 ]. Behavioural measurements of addiction were sex-specific, with females showing decreased PPI due to both PS and EE (including both the EE and PS only groups and PS + EE groups), whereas males showed an increase in PPI only due to EE (EE only and PS + EE groups) [ 51 ].

Learning and memory

Learning and memory measured by the Morris water maze, showed impaired performance due to PS in all included studies [ 52–57 ]. The effects of EE were either restorative, eliminating any impairments, as measured by the time to find platform that was similar in both controls and PS + EE, or were additive, which was reflected by improved learning and memory performance as indicated by a decrease in the time to find the hidden platform compared with controls. In all cases, EE seemed to reverse any adverse effect of PS on learning and memory performance (see Table 1 for overview).

It should also be mentioned that one study used electrophysiology [ 55 ] to study neuroplasticity associated with learning and memory functions. The study reported that long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) were altered by both PS and EE; PS impaired LTP and facilitated LTD in the hippocampus, and EE treatment counteracted the PS effect on LTP and LTD [ 55 ].

Motor skills

Behavioural tests for motor skills in PS- and EE-treated animals included the rotarod (balancing on a rotating rod), string suspension and skilled reaching tasks. PS animals across all studies showed superior performances in motor learning tasks [ 48 , 58 ]. EE however, showed differing effects, with one study showing a negative effect in motor learning tasks and reaching performance [ 58 ], and the other showing superior performance in motor tasks [ 48 ]. The major differences between these two studies were the duration of stress (G13–15 versus G14–21) and the type of stressor, one using restraint and the other using a combination of restraint, swim and mirror strength (see Table 1 ). Notably, EE had a larger benefit when the stress regimen used variable stressors and for a shorter period of time [ 48 ]. The two reports of motor performance both provided full access to exercise with the inclusion of a running wheel within the enriched housing [ 48 , 58 ].

Influence of EE on neuromorphological changes associated with PS

Four of the 15 studies pursued neuromorphological analyses including spine density of granular cells in hippocampus [ 59 ], Purkinje cell morphology (dendritic area and dendritic perimeter) and granule-to-Purkinje cell ratio [ 47 , 58 ] and T 2 relaxometry [ 54 ]. All but one study reported that PS induced neuromorphological changes. Regions of interested included the cerebellum and the hippocampus, in particular CA1 and dentate gyrus. Overall, PS decreased dendritic area and perimeter, spine density, granular cells in the HPC, and these consequences were rescued by EE (see Table 1 ). PS did not affect cerebellar morphology; however, it should be noted that there was no control for the PS condition so any change due to PS could not be measured [ 58 ]. In cerebellum, EE significantly increased the density of granule cells and the granule to Purkinje cell ratio in males. Females showed no significant alterations in cerebellar morphology.

One study used MRI T 2 relaxometry as a measure of neuronal density [ 54 ]. T 2 relaxometry measures free water concentration where an increased T 2 signal implies increased neuronal loss or possibly increased fibre density or anisotropy [ 60 , 61 ]. This study was in agreement with previous reports, showing an increase T 2 signal in the hippocampus, indicating neuronal loss [ 62 , 63 ].

Effects of EE on molecular manifestations of PS

Ten of the 15 studies assessed molecular markers as a function of PS and treatment with EE. In the 10 studies, 14 markers were used including markers of synaptic plasticity and development, neurogenesis and neuronal growth, stress response, immune regulation, attention, and fear-related learning. These changes are summarized in Table 2 and outlined below.

Table 2:

Summary of the molecular markers of prenatal stress and environmental enrichment and related outcomes

| References | Marker | Area of interest | PS | PS + EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic plasticity and development | ||||

| Koo et al. [ 52 ] | NCAM | HPC, cortex | ↓ | ↑ |

| Koo et al. [ 52 ], Li et al. [ 53 ], Lui et al. [ 54 ], Peng et al. [ 59 ] | SYP | HPC, cortex | ↓ | ↑ |

| Lui et al. [ 54 ] | NMDAR | HPC | ↓ | ↑ |

| Lui et al. [ 54 ] | b1-Integrin | HPC | ↓ | - |

| Lui et al. [ 54 ] | tPA | HPC | ↓ | - |

| Neurogenesis and neuronal growth | ||||

| Koo et al. [ 52 ] | BrdU | HPC (DG) | ↓ | ↑ |

| Koo et al. [ 52 ] | BDNF | HPC, cortex | ↓ | ↑ |

| Zhang et al. [ 56 , 57 ] | GAP-43 | HPC (P15 and P30–P50) | P15 ↑ | |

| P30- P50 ↓ | ↑ | |||

| Stress response | ||||

| Emack and Matthews [ 51 ], Laviola et al. [ 46 ], Morley-Fletcher et al. [ 77 ] | CORT | Peripheral | ♂ ↓ | ♂ ↑ ♀ ↑ |

| ↓ | ↑ | |||

| ↑ | ↓ | |||

| Li et al. [ 53 ] | GR | HPC | ↓ | ↑ |

| Immune regulation | ||||

| Laviola et al. [ 46 ] | CD 4, CD8 | Spleen, PFC | ↓ | ↑ |

| Laviola et al. [ 46 ] | IL-1β | Spleen, PFC | ↑ | ↓ |

| Activity and attention | ||||

| Emack and Matthews [ 51 ] | DRD-1 and DRD-2 | NAcc | – | ↓ |

| Fear-related learning | ||||

| Qian et al. [ 49 ] | GRPR | Amygdala | – | ↑ |

HPC, hippocampus; DG, dentate gyrus; PFC, prefrontal cortex; NAcc, nucleus accumbens

Synaptic plasticity and synapse development

Markers of synaptic plasticity in the cortex and hippocampus included neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), synaptophysin (SYP), N -methyl- d -aspartate receptor (NMDAR), b1-integrin and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). NCAM is a reliable index of synaptic density as it plays a role in neuronal plays a pivotal role in neuronal development, regeneration and synaptic plasticity [ 52 ]. SYP is a synaptic vesicle protein that is used as an index of synaptic numbers and density and indirectly as a measure of neuronal transmission [ 64 ]. Integrins are important in early programming [ 65 ] and regulate LTP and synaptic efficacy through the activation of NMDAR and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signalling cascades [ 66 ]. tPA is highly expressed in brain regions involved in learning and memory, fear and anxiety, motor learning and stress response [ 67 ]. Moreover, tPA is thought to increase synaptic strength, as it is elevated after LTP. Overall, markers of synaptic plasticity in the cortex and hippocampus revealed downregulation in PS and upregulation after EE exposure [ 52–54 , 59 ]. One exception, however, showed that a decreased expression of hippocampus b1-integrin and tPA could not be reversed by EE [ 54 ]. Both are associated with learning and memory consolidation in the adult brain, while mediating synaptic stabilization and strength [ 52 ]. These molecular changes support the behavioural findings related to learning and memory.

Neurogenesis and neuronal growth

Markers of neurogenesis and neuronal growth included 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), BDNF and growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43). BrdU is incorporated into the DNA during the cell cycle and is widely used as a mitotic marker during the development and to identify newly generated neurons in the adult brain [ 68 ]. BDNF is a neurotrophic protein which regulates activity-dependent dendritic and axonal neuroplasticity along with synapse generation and transmission [ 69–71 ]. BDNF is a prominent marker of structural and functional changes in neuronal populations. GAP-43 is involved in neurite formation, regeneration and plasticity and has shown to play a key role in stress-induced damage to the hippocampus and to regulate dendritic branching in vitro [ 72 , 73 ]. Overall, markers of neurogenesis and neuronal growth were downregulated due to PS, with the exception of one measurement at P15, where upregulation was found [ 56 ]. In contrast, these markers were upregulated by EE treatment [ 52 , 56 , 57 ].

Components of the stress response

In response to acute and chronic stress, the brain activates many hormonal pathways including the HPA axis. This response leads to the release of corticosteroid hormones from the adrenal glands, which then feedback on the brain by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs). GRs are of primary interest when investigating PS because they are activated by high levels of corticosteroids or cortisol, and they assist in terminating the stress response through negative feedback regulation. Moreover, GRs participate in memory consolidation and various other behavioural responses [ 74 ].

When comparing levels of cortisol in maternal and foetal plasma samples, researchers have shown that foetal concentrations of cortisol are linearly related to maternal concentrations [ 75 , 76 ] indicating a transfer of HPA programming from the mother to her offspring [ 4 , 5 ]. Out of the studies investigated here, only two measured stress-related physiological changes. In these two studies, baseline markers of the stress response, CORT and GR, were downregulated due to PS and upregulated due to EE [ 51 ]. In one case, CORT was upregulated in the PS group, but this occurred after an acute bout of stress, and EE further reversed this effect [ 77 ].

Other relevant measures

Other measures included markers of immune regulation as well as molecular markers linked to fear-related learning, activity and attention. Markers of immune regulation included CD4 and CD8 T Lymphocytes and interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-10 and IL-2 cytokines. These markers show an increase in inflammatory immune activity due to PS and a reversal due to EE. The measure of activity and attention included dopamine receptors (DRD 1 and 2) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1) and D2 (DRD2) are key receptors that regulate growth and differentiation of dopaminergic neurons [ 78 ] and are known to have a decreased expression during stress [ 79 ].

Fear-related learning was also measured using gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) receptors (GRPR). GRP and the GRP receptor (GRPR) are distributed throughout the central nervous system and play an important role in regulating amygdala-dependent fear-related learning [ 80 ]. Previous studies revealed that GRP modulates the expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in the amygdala [ 81 ]. Markers of activity and attention, and fear-related learning were not affected by PS in these studies, but were positively modulated by EE [ 49 ].

Discussion

The present review investigated if EE offers an effective treatment option to reverse adverse behavioural, physiological and neurological consequences associated with early programming by stress in utero . This review provides an aggregated summary of the effect of PS and EE to address the cumulative stress hypothesis, which proposes that EE mitigates adverse consequences of PS, versus the mismatch hypothesis, which proposes that EE is inefficient to reverse adverse foetal programming associated with PS. We reviewed the current findings on PS and postnatal EE to determine if EE provides a suitable treatment option to reverse adverse effects of PS.

Of the initial number of captured studies, 15 were eligible for review. These 15 studies specifically investigated behavioural, physiological, neuromorphological or molecular aspects of PS and postnatal EE therapy. Although there was a limited number of studies conducted on PS and EE, across all studies, EE seems to have overall beneficial effects on animals that were prenatally stressed. This review revealed that EE, for the most part, reverses behavioural, morphological and molecular consequences of PS. The efficacy of EE, however, may depend on the timing and variability of stress and EE exposure, susceptibility and resilience to PS, and is especially dependent on the application of exercise. Thus, the findings of this report support the cumulative stress hypothesis suggesting that EE offsets the cumulative wear and tear induced by PS and subsequent HPA axis programming and elevated stress sensitivity. However, as discussed further below, the mismatch hypothesis and cumulative stress hypothesis may interact and be influential during different critical periods and life circumstances. Overall, it seems as though EE may present an effective and clinically relevant experience-based therapy to treat stress-associated disorders and consequences of early trauma.

The influence of variability, timing, vulnerability and resilience

It is apparent that differences in the nature and intensity of PS affect the severity of symptoms and therefore the effectiveness of enrichment therapy. In terms of timing, one study found that enrichment did not reverse the main effects of PS; however, the stress paradigm used in this study was unpredictable and could be considered severe [ 51 ]. The results of this study suggest that shorter bouts of stress, or acute stress late in pregnancy, may have greater long-term effects on HPA activity and related behaviours. Where stress was unpredictable and variable, enrichment did not improve learning and memory or alter SYP levels in the hippocampus [ 51 ]. On the other hand, another study found that enrichment had a larger positive effect on motor abilities when stress was more variable for an acute time period [ 48 ]. This observation could indicate that the timing and variability may affect behavioural functions and systems differently (motor versus cognitive functions). In terms of severity, the most severe stressor included in this review was 6 h of restraint stress daily for 8 days during late pregnancy [ 54 ]. This study found that EE was not able to reverse the molecular deficits in b1-integrin and tPA in the HPC that were generated by PS.

Another consideration is that individual animals, depending on their sex, species and/or age may respond differently to PS based on transgenerationally programmed stress resilience and stress vulnerability [ 16 , 82 ]. Evidence points to large variations in phenotype observed among PS individuals in a study that suggests differences in vulnerability and resilience to PS [ 83 ]. Stress resilience and vulnerability, according to the mismatch hypothesis, may be related to stress imposed during the prenatal environment as well as to the possible stress induced by enrichment. The stress associated with enrichment may pertain to extensive physical exercise, the encounter of novel objects, the presence of social competitors and larger, open spaces which the animals may perceive as threatening.

Vulnerable individuals may present with a recurrent maladaptive response to stressors and resilient individuals may recognize a stressful situation as minimally threatening enabling the development of a more appropriate, adaptive physiological and psychological response [ 84 ]. Although these changes were not addressed directly by the articles subject to this review and there was limited work that included females, the data suggest a slight sex difference. It seems that PS causes females to become more vulnerable to stress of enrichment, and males to be more affected by the PS itself. For example, one study showed that enrichment had an opposite effect in males and females where enrichment in females diminished the ability of sensorimotor gating in PPI tests. Furthermore, in another study, prenatally stressed females showed no significant alterations in cerebellar morphology indicating greater resilience to stress due to PS [ 47 ]. These results help confirm the role of sex steroids in stress vulnerability and resilience [ 51 ]. However, the number of studies including both males and females was only 3 of 15 articles. It is therefore important to include the underrepresented females in future studies to more thoroughly understand sexual dimorphisms in the response to PS and EE.

It should be noted that although previous animal studies have indicated variability in stress resilience or vulnerability as a function of strain, there were no strain differences noted in the studies included in this review. Studies have suggested that Wistar rats may be more ‘anxious’ compared with the Sprague Dawley strain [ 85 ]. These results could suggest that intra-strain differences may play a role in stress response and the effectiveness of EE. According to the mismatch hypothesis, it is possible that the susceptibly anxious Wistar rats would be less likely to benefit from EE exposure.

The cumulative stress and the mismatch hypotheses may also play variable roles at different time periods in life. Therefore, an important consideration concerns the age of the animals at which they were housed in an EE. It has been suggested that individual differences in early programming and the postnatal environment encountered during critical periods of brain development determine whether the cumulative stress hypothesis or the mismatch hypothesis is more applicable [ 84 ]. In the majority of studies in rats, EE was applied at weaning, on or around postnatal day (P) 21, and measurements were collected approximately in adolescence (at P60). However, one group investigated GAP-43 expression at three time points; pre-weaning, pre-puberty and early adolescence, with EE subjected at P10-P30 [56, 57]. Here, GAP-43 expression increased significantly on P15 and then decreased from P30 to P50. This indicates that during earlier stages, the response to PS may be restorative or protective for the nervous system, and later ages may indicate a rather maladaptive response to PS. Lastly, the timing of enrichment calls for the need to mention the application of maternal enrichment. Although the focus of this review was primarily enrichment in offspring who were subject to PS in utero , it should be noted that enrichment has also been applied during pre-reproductive and prenatal stages to influence offspring stress reactivity later in life [ 86 , 87 ].

Exercise as an essential component in enrichment

Each of the reported studies, except one, involved enrichment paradigms that were designed to stimulate physical exercise. This particular aspect of enrichment may have the largest influence on functional improvements in prenatally stressed animals [ 88 ]. Supporting studies have been designed to measure the effect of the physical exercise component of EE. One such study compared voluntary and forced activity with or without the addition of a learning task in hippocampal neurogenesis of adult mice [ 89 ]. Their results showed that neurogenesis was only increased in mice that had voluntary access to running wheels [ 89 ]. In line with this finding, the one study included in this review that did not result in beneficial effects used an EE that lacked an exercise paradigm [ 51 ]. Thus, the inclusion of an exercise facility in the EE may be vital for its benefit. Moreover, in paradigms that lacked social enrichment, there seemed to be no less beneficial effect of enrichment, further emphasizing the positive benefits of physical enrichment. Recently, a group of researchers proposed a standardized EE design, which may assist in obtaining more consistent results across studies [ 90 ].

Future implications

Enriched environment as a therapy for ancestral stress

Growing evidence indicates that programming by PS not only affects the F1 generation, but also propagates to further generations of offspring [ 13 , 16 , 91 ]. Transgenerational programming by PS or postnatal trauma across two or three filial generations of the paternal and maternal lineages have been suspected to alter stress response [ 91 , 92 ], elevate risk of metabolic disorders [ 93 ] and psychopathologies [ 13 ] and promote pregnancy complications [ 16 ]. Since exposure to ancestral stress is uncontrollable to the filial generations, a vital question is whether EE presents an effective therapy to protect or even reverse adverse health outcomes in a stress lineage. Indeed, our findings suggest that EE is able to restore phenotypic and epigenetic manifestations linked to ancestral PS [ 94 ]. This work supported a central role for epigenetic modifications as one of the primary mechanisms of stress transfer and reversal by EE. Epigenetic changes can be brought on by prenatal experiences prenatally, during development, or be passed on from the parent to the offspring [ 83 , 95 ]. Because epigenetic regulators readily respond to environmental conditions and so allow rapid modifications to a changing environment, these processes may advance the discovery of predictive epigenetic signatures linked to disease and initiate the discovery of new diagnostics and therapeutic interventions for future generations. Due to the implications and seemingly large role of epigenetics in the efficacy of EE, it is also important to consider underlying epigenetic and genetic vulnerabilities, especially when designing and developing interventions for the human population [ 96 ].

Implications for EE therapy in human populations

Although the studies included in this review are limited to animal models, it is likely that the benefits of EE would be seen in similar human populations. However, as mentioned above, animal models of EE may be simulating standard human conditions, whereas control environments may be considered as impoverished. Although this concept is important in all experimental projects using animal models, it is especially important when applying variables to the environment such as enrichment. However, despite this potential difference in translation, the results from this review demonstrate the potential use of enrichment therapies in human populations affected by prenatal or ancestral stress. Surmounting evidence from human epidemiological studies suggest that PS raises risk of metabolic diseases and stress-related psychopathologies [ 97 ]. Earlier reports indicated that a broad range of experiential treatments, such as mindfulness meditation [ 36 ], music lessons [ 37 ] and physical activities [ 38 ] promote a healthy human lifestyle. Although these treatments vary greatly in their delivery, all have shown to act on similar biological and physiological systems, by decreasing cortisol and promoting neurogenesis and neural repair [ 98 , 99 ]. Based on the promising findings from such experiential therapies, it is reasonable to assume that a more complex experiential therapy, which combines aspects of social and physical enrichment, has beneficial effects on health outcomes in prenatally stressed individuals or other populations at risk. For example, strategies that involve Centering Pregnancy ® to form social support groups for prenatal care were proved successful in promoting maternal and newborn health outcomes [ 100 , 101 ]. Community support groups or policies that facilitate access to lifestyle enrichment may be central prerequisites to develop an effective strategy that targets improved health outcomes in communities.

Conclusions

The last decade is highlighted by considerable efforts to unravel the mechanisms of how maternal stress impacts offspring lifetime health trajectories. Although the consequences of maternal stress can be complex and long-lasting, there still is no recognized therapeutic approach to offset the consequences of adverse programming by PS. In this review, the articles included suggest effectiveness of postnatal EE to treat adverse outcomes associated with PS in terms of behavioural, physiological and neural deficit as long as physical exercise is a part of the enrichment paradigm. Differing responses to EE may be dependent on the timing and variability of and postnatal enrichment, the delivery of effective parental care, and the inherent resiliency or vulnerability of the phenotypes to PS. The advanced understanding of the mismatch hypothesis and the vulnerability to postnatal environments may help us understand how EE can be catered towards individuals at risk. We also suggest that studies should be conducted which allow for the consideration of the ‘Differential Susceptibility’ model which indicates that individuals most adversely affected by stress may be the same individuals who acquire the most benefit from EE [ 102 ]. This may also contribute to the knowledge of using EE for higher risk clinical populations.

The present analysis illustrates the relatively small number of studies that addressed EE therapy in the context of PS and recommend cautionary, yet anticipative, conclusions due to the variability in stress and enrichment procedures, and the lack of data in females. Future studies therefore should consider sex differences and also include advanced ‘omics technologies, such as epigenomics, in order to identify potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Since adverse experience linked to PS is reflected by or even causally linked to epigenetic marks, EE may provide a suitable therapy to reverse stress-associated epigenetic changes through beneficial experience. Overall, the present analysis suggests that EE may be a powerful and clinically relevant multi-modal experience-based therapy to treat stress-associated disorders and consequences of early trauma in populations put at risk by limited opportunity and lack of social support.

Methods

In March 2015, Web of Science and Pub Med were searched for ‘Enrichment’ or ‘Enriched Environment’ and ‘Prenatal Stress’ after a qualified librarian helped to provide the most effective search strategy. After the independent captures were merged and duplicates removed, the initial search yielded a total of 183 articles. Eligibility criteria included English articles, non-conference proceedings and research articles. There were no limitations set on the year of publication and all articles were published relatively recently between 2003 and 2015. There were no research-based articles that involved human subjects, so all articles reported in the following pertain to animal studies of PS and EE. Animal models included PS and enrichment in one guinea pig model, one CF-1 mouse model and the remainder were conducted in Sprague Dawley or Wistar rats. A final capture of 15 articles was used for full analysis and data extraction. The limited number of articles was due to the amount of studies specifically investigating PS (as opposed to acute or chronic postnatal stress) and postnatal offspring enrichment (as opposed to maternal enrichment or prenatal enrichment). Studies that focused on multiple treatment groups (i.e. treating an additional group with pharmacological intervention) in addition to PS and offspring enrichment were included, but only the groups of interest were included in the data extraction.

Summarized here are the types of PS and EE used in the studies, and the overall behavioural, morphological and molecular changes induced by PS and EE. Emphasis was placed on studies relating to brain and behaviour, i.e. the effectiveness of EE in reversing behavioural and neuronal deficits due to PS.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions Interdisciplinary Team Grant #200700595 ‘Preterm Birth and Healthy Outcomes’ (G.M.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant #102652 (G.M.), the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada DG #298194-20009 (G.M.) and National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada CREATE to Philippe Teillet #371155 (J.M.).

References

- 1. Woods S, Melville J, Guo Y. et al. . Psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010. ; 202 : e61 – 7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koolhaas J, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B. et al. . Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011. ; 35 : 1291 – 301 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Migeon C, Prystowsky H, Grumbach M. et al. . Placental passage of 17-hydroxycorticosteroids: comparison of the levels in maternal and fetal plasma and effect of ACTH and hydrocortisone administration. J Clin Invest 1956. ; 35 : 488 – 93 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glover V, Bergman K, Sarkar P. et al. . Association between maternal and amniotic fluid cortisol is moderated by maternal anxiety. Psychoneuroendocrino 2009. ; 34 : 430 – 5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bosch O, Musch W, Bredewold R. et al. . Prenatal stress increases HPA axis activity and impairs maternal care in lactating female offspring: implications for postpartum mood disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007. ; 32 : 267 – 78 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Champagne F, Weaver I, Diorio J. et al. . Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology 2006. ; 147 : 2909 – 15 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meaney M. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001. ; 24 : 1161 – 92 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mashoodh R, Franks B, Curley J. et al. . Paternal social enrichment effects on maternal behavior and offspring growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012. ; 109 : 17232 – 8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mychasiuk R, Harker A, Ilnytskyy S. et al. . Paternal stress prior to conception alters DNA methylation and behaviour of developing rat offspring. Neuroscience 2013. ; 241 : 100 – 5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mueller B, Bale T. Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci 2008. ; 28 : 9055 – 65 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oberlander T, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M. et al. . Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics 2008. ; 3 : 97 – 106 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Migicovsky Z, Kovalchuk I. Epigenetic memory in mammals. Front Genet 2011. ; 2 : 28.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Babenko O, Kovalchuk I, Metz G. Stress-induced perinatal and transgenerational epigenetic programming of brain development and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015. ; 48 : 70 – 91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nilsson E, Skinner M. Environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of reproductive disease. Biol Reprod 2015. ; 93 : 145.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glover V. Annual research review: prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011. ; 52 : 356 – 67 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yao Y, Robinson A, Zucchi F. et al. . Ancestral exposure to stress epigenetically programs preterm birth risk and adverse maternal and newborn outcomes. BMC Med 2014. ; 12 : 121.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arck P. Stress and pregnancy loss: role of immune mediators, hormones and neurotransmitters. Am J Reprod Immunol 2001. ; 46 : 117 – 23 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindsay R, Lindsay R, Waddell B. et al. . Prenatal glucocorticoid exposure leads to offspring hyperglycaemia in the rat: studies with the 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor carbenoxolone. Diabetologia 1996. ; 39 : 1299 – 305 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mychasiuk R, Gibb R, Kolb B. Prenatal stress alters dendritic morphology and synaptic connectivity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of developing offspring. Synapse 2012. ; 66 : 308 – 14 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ronald A, Pennell C, Whitehouse A. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Front Psychol 2010. ; 1 : 223.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Charil A, Laplante D, Vaillancourt C. et al. . Prenatal stress and brain development. Brain Res Rev 2010. ; 65 : 56 – 79 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zucchi, Yao Y, Ward I. et al. . Maternal stress induces epigenetic signatures of psychiatric and neurological diseases in the offspring. PLoS One 2013. ; 8 : e56967.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Skinner M. Environmental stress and epigenetic transgenerational inheritance. BMC Med 2014. ; 12 : 153.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hebb DO. The effects of early experience on problem solving at maturity. Am Psychol 1947. ; 2 : 306 – 7 . [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clarke R, Heron W, Fetherstonhaugh M. et al. . Individual differences in dogs: preliminary report on the effects of early experience. Can J Psychol 1951. ; 5 : 150 – 6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenzweig M, Krech D, Bennett EL. et al. . Variation in environmental complexity and brain measures. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1962. ; 55 : 1092 – 5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett EL, Diamond M, Krech D. et al. . Chemical and anatomical plasticity brain. Science 1964. ; 146 : 610 – 9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jung C, Herms J. Structural dynamics of dendritic spines are influenced by an environmental enrichment: an in vivo imaging study. Cereb Cortex 2014. ; 24 : 377 – 84 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Falkenberg T, Mohammed A, Henriksson B. et al. . Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in rat hippocampus is associated with improved spatial memory and enriched environment. Neurosci Lett 1992. ; 138 : 153 – 6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Branchi I, Karpova N, D'Andrea I. et al. . Epigenetic modifications induced by early enrichment are associated with changes in timing of induction of BDNF expression. Neurosci Lett 2011. ; 495 : 168 – 72 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kolb B, Gibb R. Environmental enrichment and cortical injury: behavioral and anatomical consequences of frontal cortex lesions. Cereb Cortex 1991. ; 1 : 189 – 98 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Knieling M, Metz G, Antonow-Schlorke I. et al. . Enriched environment promotes efficiency of compensatory movements after cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience 2009. ; 163 : 759 – 69 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fischer F, Peduzzi J. Functional recovery in rats with chronic spinal cord injuries after exposure to an enriched environment. J Spinal Cord Med 2007. ; 30 : 147 – 55 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jadavji N, Kolb B, Metz G. Enriched environment improves motor function in intact and unilateral dopamine-depleted rats. Neuroscience 2006. ; 140 : 1127 – 38 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jadavji N, Metz G. Both pre- and post-lesion experiential therapy is beneficial in 6-hydroxydopamine dopamine-depleted female rats . Neuroscience 2009. ; 158 : 373 – 86 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lutz A, Slagter H, Dunne J. et al. . Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci 2008. ; 12 : 163 – 9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Metzler M, Saucier D, Metz G. Enriched childhood experiences moderate age-related motor and cognitive decline. Front Behav Neurosci 2013. ; 7 : 1 – 8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anderson E, Shivakumar G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front Psychiatry 2013. ; 4 : 27.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larsson F, Winblad B, Mohammed A. Psychological stress and environmental adaptation in enriched vs. impoverished housed rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2002. ; 73 : 193 – 207 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marashi V, Barnekow A, Ossendorf E. et al. . Effects of different forms of environmental enrichment on behavioral, endocrinological, and immunological parameters in male mice. Horm Behav 2003. ; 43 : 281 – 92 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moncek F, Duncko R, Johansson B. et al. . Effect of environmental enrichment on stress related systems in rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2004. ; 16 : 423 – 31 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nederhof E, Schmidt M. Mismatch or cumulative stress: toward an integrated hypothesis of programming effects. Physiol Behav 2012. ; 106 : 691 – 700 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nederhof E. The mismatch hypothesis of psychiatric disease. Physiol Behav 2012. ; 106 : 689 – 90 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santarelli S, Lesuis S, Wang X. et al. . Evidence supporting the match/mismatch hypothesis of psychiatric disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014. ; 24 : 907 – 18 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Karatsoreos I, McEwen B. Psychobiological allostasis: resistance, resilience and vulnerability. Trends Cogn Sci 2011. ; 15 : 576 – 84 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laviola G, Rea M, Morley-Fletcher S. et al. . Beneficial effects of enriched environment on adolescent rats from stressed pregnancies. Eur J Neurosci 2004. ; 20 : 1655 – 64 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pascual R, Valencia M, Bustamante C. Purkinje cell dendritic atrophy induced by prenatal stress is mitigated by early environmental enrichment. Neuropediatrics 2015. ; 46 : 37 – 43 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zubedat S, Aga-Mizrachi S, Cymerblit-Sabba A. et al. . Methylphenidate and environmental enrichment ameliorate the deleterious effects of prenatal stress on attention functioning. Stress 2015. ; 18 : 1 – 9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Qian J, Zhou D, Pan F. et al. . Effect of environmental enrichment on fearful behavior and gastrin-releasing peptide receptor expression in the amygdala of prenatal stressed rats. J Neurosci Res 2008. ; 86 : 3011 – 7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang J, Li W, Liu X. et al. . Enriched environment treatment counteracts enhanced addictive and depressive-like behavior induced by prenatal chronic stress. Brain Res 2006. ; 1125 : 132 – 7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Emack J, Matthews S. Effects of chronic maternal stress on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) function and behavior: No reversal by environmental enrichment. Horm Behav 2011. ; 60 : 589 – 98 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Koo J, Park C, Choi S. et al. . Postnatal environment can counteract prenatal effects on cognitive ability, cell proliferation, and synaptic protein expression. FASEB J 2003. ; 17 : 1556 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li M, Wang M, Ding S. et al. . Environmental enrichment during gestation improves behavior consequences and synaptic plasticity in hippocampus of prenatal-stressed offspring rats . Acta Histochem Cytochem 2012. ; 45 : 157 – 66 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lui C, Wang J, Tain Y. et al. . Prenatal stress in rat causes long-term spatial memory deficit and hippocampus MRI abnormality: differential effects of postweaning enriched environment. Neurochem Int 2011. ; 58 : 434 – 41 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang J, Hou C, Ma N. et al. . Enriched environment treatment restores impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity and cognitive deficits induced by prenatal chronic stress. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2007. ; 87 : 257 – 63 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Z, Zhang H, Du B. et al. . Enriched environment upregulates growth-associated protein 43 expression in the hippocampus and enhances cognitive abilities in prenatally stressed rat offspring. Neural Regen Res 2012. ; 7 : 1967 – 73 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang Z, Zhang H, Du B. et al. . Neonatal handling and environmental enrichment increase the expression of GAP-43 in the hippocampus and promote cognitive abilities in prenatally stressed rat offspring. Neurosci Lett 2012. ; 522 : 1 – 5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ulupinar E, Erol K, Aya H. et al. . Rearing conditions differently affect the motor performance and cerebellar morphology of prenatally stressed juvenile rats. Behav Brain Res 2015. ; 278 : 235 – 43 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Peng Y, Jian X, Liu L. et al. . Influence of environmental enrichment on hippocampal synapses in adolescent offspring of mothers exposed to prenatal stress. Neural Regen Res 2011. ; 6 : 378 – 82 . [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jansen J, Lemmens E, Strijkers G. et al. . Short- and long-term limbic abnormalities after experimental febrile seizures. Neurobiol Dis 2008. ; 32 : 293 – 301 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. MiotNoirault E, Barantin L, Akoka S. et al. . T2 relaxation time as a marker of brain myelination: Experimental MR study in two neonatal animal models. J Neurosci Methods 1997. ; 72 : 5 – 14 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kalviainen R, Laakso M, Partanen K. et al. . Elevated magnetic-resonance T2 relaxation-time as a marker of Hippocampal pathology in temporal-lobe epilepsy - a comparison to Alzheimers-disease. Neurology 1995. ; 45 : A403 . [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kalviainen R, Partanen K, Aikia M. et al. . MRI-based hippocampal volumetry and T2 relaxometry: correlation to verbal memory performance in newly diagnosed epilepsy patients with left-sided temporal lobe focus. Neurology 1997. ; 48 : 286 – 7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nakamura H, Kobayashi S, Ohashi Y. et al. . Age-changes of brain synapses and synaptic plasticity in response to an enriched environment. J Neurosci Res 1999. ; 56 : 307 – 15 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huang F, Huang K, Wu J. et al. . Environmental enrichment enhances neurogranin expression and hippocampal learning and memory but fails to rescue the impairments of neurogranin null mutant mice. J Neurosci 2006. ; 26 : 6230 – 7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Shi Y, Ethell I. Integrins control dendritic spine plasticity in hippocampal neurons through NMDA receptor and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-mediated actin reorganization. J Neurosci 2006. ; 26 : 1813 – 22 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Melchor J, Strickland S. Tissue plasminogen activator in central nervous system physiology and pathology. Thromb Haemost 2005. ; 93 : 655 – 60 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kolb B, Pedersen B, Ballermann M. et al. . Embryonic and postnatal injections of bromodeoxyuridine produce age-dependent morphological and behavioral abnormalities. J Neurosci 1999. ; 19 : 2337 – 46 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schinder AF, Poo M. The neurotrophin hypothesis for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci 2000. ; 23 : 639 – 45 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and neuronal plasticity. Science 1995. ; 270 : 593 – 8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Levine E, Dreyfus C, Black I. et al. . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rapidly enhances synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons via postsynaptic tyrosine kinase receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995. ; 92 : 8074 – 7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chao H, McEwen B. Glucocorticoids and the expression of mRNAs for neurotrophins, their receptors and GAP-43 in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1994. ; 26 : 271 – 6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gauthier-Campbell C, Bredt D, Murphy T. et al. . Regulation of dendritic branching and filopodia formation in hippocampal neurons by specific acylated protein motifs. Mol Biol Cell 2004. ; 15 : 2205 – 17 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. de Kloet E, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005. ; 6 : 463 – 75 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gitau R, Cameron A, Fisk N. et al. . Fetal exposure to maternal cortisol. Lancet 1998. ; 352 : 707 – 8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gitau R, Fisk N, Teixeira J. et al. . Fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress responses to invasive procedures are independent of maternal responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001. ; 86 : 104 – 9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Morley-Fletcher S, Rea M, Maccari S. et al. . Environmental enrichment during adolescence reverses the effects of prenatal stress on play behaviour and HPA axis reactivity in rats. Eur J Neurosci 2003. ; 18 : 3367 – 3374 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cabib S, Puglisi-Allegra S. The mesoaccumbens dopamine in coping with stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2012. ; 36 : 79 – 89 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Scheggi S, Marchese G, Grappi S. et al. . Cocaine sensitization models an anhedonia-like condition in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011. ; 14 : 333 – 46 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shumyatsky G, Tsvetkov E, Malleret G. et al. . Identification of a signaling network in lateral nucleus of amygdala important for inhibiting memory specifically related to learned fear. Cell 2002. ; 111 : 905 – 18 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kent P, Anisman H, Merali Z. Central bombesin activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Effects on regional levels and release of corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine-vasopressin. Neuroendocrinology 2001. ; 73 : 203 – 214 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Franklin T, Russig H, Weiss I. et al. . Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biol Psychiatry 2010. ; 68 : 408 – 15 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Boersma G, Tamashiro K. Individual differences in the effects of prenatal stress exposure in rodents. Neurobiol Stress 2015. ; 1 : 100 – 8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Franklin T, Saab B, Mansuy I. Neural mechanisms of stress resilience and vulnerability. Neuron 2012. ; 75 : 747 – 61 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rex A, Voigt J, Gustedt C. et al. . Anxiolytic-like profile in Wistar, but not Sprague-Dawley rats in the social interaction test. Psychopharmacol (Berl) 2004. ; 177 : 23 – 34 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Caporali P, Cutuli D, Gelfo F. et al. . Pre-reproductive maternal enrichment influences offspring developmental trajectories: motor behavior and neurotrophin expression. Front Behav Neurosci 2014. ; 8 : 1 – 14 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cymerblit-Sabba A, Lasri T, Gruper M. et al. . Prenatal enriched environment improves emotional and attentional reactivity to adulthood stress. Behav Brain Res 2013. ; 241 : 185 – 90 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Harburger L, Nzerem C, Frick K. : Single enrichment variables differentially reduce age-related memory decline in female mice. Behav Neurosci 2007. ; 121 : 679 – 688 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage F. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci 1999. ; 2 : 266 – 70 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Fares RP,, Kouchi H,, Bezin L. Standardized environmental enrichment for rodents in Marlau cage. Protocol Exchange 2012. . doi: 10.1038/protex.2012.036.

- 91. Zucchi F, Yao Y, Metz G. The secret language of destiny: stress imprinting and transgenerational origins of disease. Front Genet 2012. ; 3 : 96.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Morgan C, Bale T. Prenatal stress and transgenerational epigenetic programming via the paternal lineage. FASEB J 2011. ; 25 : 307.4 . [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yehuda R, Engel S, Brand S. et al. . Transgenerational effects of posttraumatic stress disorder in babies of mothers exposed to the world trade center attacks during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005. ; 90 : 4115 – 8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. McCreary JK,, Erickson ZT,, Babenko A. et al. . Environmental enrichment reverses transgenerational programming by early trauma. In: International Behavioural Neuroscience Society Annual Meeting: 2015; Victoria, Canada , 2015. .

- 95. Meaney M, Szyf M. Maternal care as a model for experience-dependent chromatin plasticity? Trends Neurosci 2005. ; 28 : 456 – 63 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Champagne F. Early adversity and developmental outcomes: interaction between genetics, epigenetics, and social experiences across the life span. Perspect Psychol Sci 2010. ; 5 : 564 – 74 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Entringer S. Impact of stress and stress physiology during pregnancy on child metabolic function and obesity risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2013. ; 16 : 320 – 7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jin P. Efficacy of Tai Chi, brisk walking, meditation, and reading in reducing mental and emotional stress. J Psychosom Res 1992. ; 36 : 361 – 70 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Fukui H, Toyoshima K. Music facilitate the neurogenesis, regeneration and repair of neurons. Med Hypotheses 2008. ; 71 : 765 – 9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Benediktsson I, McDonald S, Vekved M. et al. . Comparing CenteringPregnancy(R) to standard prenatal care plus prenatal education. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013. ; 13(Suppl 1) : S5.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Trotman G, Chhatre G, Darolia R. et al. . The effect of centering pregnancy versus traditional prenatal care models on improved adolescent health behaviors in the perinatal period. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2015. ; 28 : 395 – 401 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull 2009. ; 135 : 885 – 908 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]