Abstract

Mitigating the harmful effects of adverse social conditions is critical to promoting optimal health and development throughout the life course. Many Canadians worry over food access or struggle with household food insecurity. Public policy positions breastfeeding as a step toward eradicating poverty. Breastfeeding fulfills food security criteria by providing the infant access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets dietary needs and food preferences. Unfortunately, a breastfeeding paradox exists where infants of low-income families who would most gain from the health benefits, are least likely to breastfeed. Solving household food insecurity and breastfeeding rates may be best realized at the public policy level. Notably, the health care provider’s competencies as medical expert, professional, communicator and advocate are paramount. Our commentary aims to highlight the critical link between breastfeeding and household food insecurity that may provide opportunities to affect clinical practice, public policy and child health outcomes.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Child health, Food insecurity, Paediatrician, Social paediatrics.

Mitigating the effect of harmful social determinants is critical to promoting optimal child health throughout the life course (1). Many Canadian households worry over food access. Overwhelming evidence links poverty and food insecurity to poor health outcomes. Canadian public policy positions breastfeeding as important to improving household food insecurity (HFI) and a step toward eradicating poverty (2). Sharpening public policy to provide optimal nutrition during sensitive periods of development may be essential to improving child health outcomes. Our commentary aims to highlight the critical link between breastfeeding and HFI. It outlines required competencies of the health care provider (HCP) that may provide opportunities to affect clinical practice, public policy and child health outcomes.

BREASTFEEDING: HEALTH BENEFITS AND THE BREASTFEEDING PARADOX

Breastfeeding provides the ideal infant nourishment. Infants benefit from a reduction in diseases including asthma, diabetes mellitus and obesity. Breastfeeding can improve mental health and promote healthy infant attachment (3). As well, healthy brain development and lifespan effects of intelligence, educational attainment and later income may be better in breastfed than formula-fed infants (4). Breastfeeding offers maternal benefits, such as postpregnancy weight loss, delayed menstruation and may reduce the risk of noncommunicable diseases, including ovarian and breast cancer, diabetes and obesity (5). Societal benefits of breastfeeding include increased human capital, decreased health systems utilization and smaller carbon footprint.

Importantly, breastfeeding can help to reduce health inequalities. A paradoxical link exists between low-income households and low breastfeeding practice, where ‘women who can least afford to buy infant formula, and whose babies are in greatest need of the protection and health-promoting qualities of breast milk, are the least likely to breastfeed’ (6). Ensuring that all newborns are breastfed can act as a small step toward eliminating poverty and to provide infant food security.

HOUSEHOLD FOOD INSECURITY: DEFINITION, RATES, HEALTH RISKS AND INQUIRY

For an active and healthy life, food security is required for household members to access sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets needs and preferences (7). Whereas, HFI encompasses a range of experiences including worrying over food access and various degrees of food deprivation (8). HFI is a serious public health concern, particularly for young children (7). HFI varies dramatically between provinces and territories. Alarmingly, one in six Canadian children live with food insecurity (9).

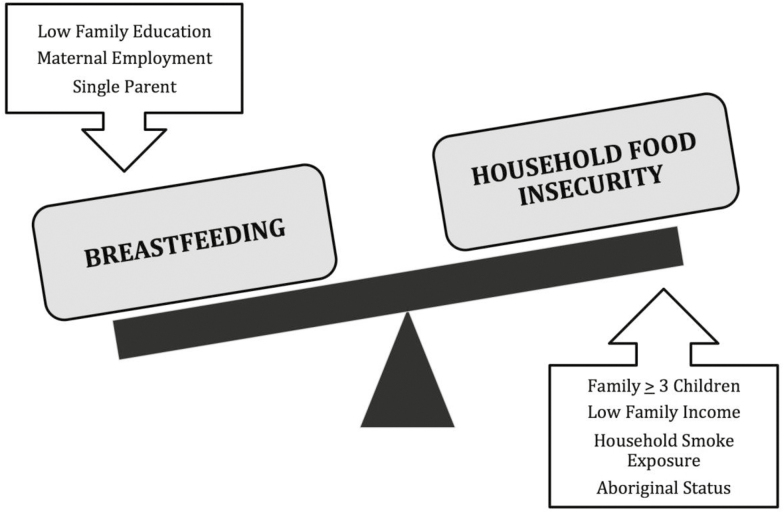

Many Canadian households report food insecurity. In 2014, 12% of Canadian households were food insecure and 3% were severely food insecure with reduced food intake (7). HFI in provinces ranged from 10% in Saskatchewan to 15% in Nova Scotia. In the territories, the prevalence of food insecurity was higher: Northwest Territories (24%) and Nunavut (47%) (9–11). Almost half of low-income families reported HFI. Social assistance recipients were exceptionally vulnerable to HFI with the highest rate in Nova Scotia (above 80%) and the lowest rate in Alberta (62%) (9). Households with single parents, young children, low education, Aboriginal status, household smoke exposure and urban residence were at increased risk (10) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Breastfeeding and household food insecurity: conceptual model.

Children experience adverse health attributed to inadequate quality and quantity of food (7,8,12). They are more likely to report poor health, frequent hospitalizations and suffer from chronic illnesses, such as asthma and obesity, compared to food secure children (12). In addition, food insecurity can impair the child’s ability to concentrate and perform at school (8). Children experience increased mental health concerns, including depression, anxiety, attention deficit disorders and emotional problems. In food insecure households, caregivers have increased depression and poorer self-reported health status, and are less sensitive to children’s needs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Health associations with household food insecurity

| Infant | Weakened parental attachment |

| Child | Poor performance on language comprehension tests |

| Inability to follow directions | |

| Delays in socioemotional, cognitive and motor development | |

| Hyperactivity/inattention and poor memory | |

| Chronic illness and childhood obesity | |

| Youth | Depression and suicidal ideation |

| Mood and substance abuse disorders | |

| Maternal and family | Maternal depression |

| Maternal post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse | |

| Unresponsive caring practices |

Adapted from ref. (21).

Food insecurity is an urgent human right and social justice concern. It requires action at all levels of government. Food banks and soup kitchens offer only temporary relief from hunger, may undermine family dignity and deny the basic right to food. Importantly, food charities do neither resolve HFI nor address the underlying root cause of poverty. The Canadian Paediatric Society supports a poverty reduction strategy (13). A guaranteed family income may be a sustainable approach to addressing the root cause of food insecurity.

THE CONNECTION

The impact of breastfeeding on HFI is undeniable (Figure 1). Breastfeeding provides access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets the dietary needs and food preferences of the infant. It fulfills the criteria for providing adequate food security, which is ideal infant nourishment to maintain a healthy and active life. Among households with a concern of food insecurity, breastfeeding has been used as a food production system, however the main reason for cessation was the worry that breast milk was not sufficient or healthy (14).

Breastfeeding provides food security for families. Family resources can be redirected to secure food for the household. The purchase of breast milk substitutes can use much of the household income and threaten the food security of the entire family. In addition, healthier breastfed infants can save family resources by avoiding health care costs, lost work time and health care visits.

Limited evidence between breastfeeding and HFI from comparable high-income countries is inconsistent. US study data reported no association between breastfeeding and HFI in mother–infant pairs participating in the Special Supplement Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (15). In contrast, a study of Massachusetts WIC mothers found that prenatal HFI was associated with a lower breastfeeding initiation and postpartum HFI was associated with greater breastfeeding duration compared to those who were food secure (16). Whereas, another US study using NHANES data found that mothers with HFI had lower breastfeeding initiation and duration, compared to mothers from food secure households (17). In comparison, the Canadian experience using data from Canadian Community Health Survey showed that mothers with HFI were as likely to initiate breastfeeding but stopped exclusively breastfeeding earlier compared to food secure households (18).

The breastfeeding paradox assumes that infant formula cost and reduced household resources contribute to HFI. On the other hand, countries with inadequate maternity leave, breastfeeding might worsen HFI by preventing maternal employment participation. In high-income countries, access to maternity leave has increased breastfeeding duration in low-income groups. Lower breastfeeding rates were associated with women who were non-managerial employees, lacked job flexibility or experienced psychosocial distress (19).

COMPETENCIES OF THE HCP

Capitalizing on the influential role of the HCP, we examine the following competencies:

Medical expert

Trust and access to families make the HCP’s role unique. The HCP can provide patient-centred care by addressing health goals that reflect the family needs, values and preferences while being sensitive to the risk of stigmatizing mothers who choose not to breastfeed. The medical expert emphasizes the health benefits of breastfeeding, creates the supportive environment and refers to appropriate community resources.

Professional

The HCP can work with local public health units, community agencies and hospitals to provide seamless transition of services, round-the-clock breastfeeding support and innovative community partnerships that reach high-risk families.

Collaborator

The HCP can work with local clinics and hospital to implement the ‘Ten steps to successful breastfeeding’ (Box 1). The key areas are to implement a breastfeeding policy, inform mothers and families about the health benefits of breastfeeding and assist mothers to breastfeed and maintain lactation.

Box 1. Ten steps to successful breastfeeding for the health care provider

Have a written breastfeeding policy that is regularly communicated to staff.

Train all health care staff in skills necessary to implement the breastfeeding policy.

Inform all families about the health benefits of breastfeeding.

Encourage all mothers to initiate breastfeeding within the first half hour after birth.

Encourage and show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation if they are separated from their infant.

Encourage exclusive breastfeeding (no food or drink other than breast milk) unless medically indicated in the first 6 months.

Provide a comfortable space for mothers to breastfeed or pump breast milk.

Encourage breastfeeding on demand.

Give no artificial teats or pacifiers to breastfeeding infants.

Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers.

Adapted from ref. (22).

Communicator

The HCP can recognize the ‘breastfeeding paradox’ and the relationship to HFI and poverty. The communicator can share with families evidence-based concerns of HFI with lifelong health and social consequences. The HCP can adopt universal screening for HFI using a two-question screening tool (20) (Box 2). The HCP can address factors that affect HFI, such as media messaging, food affordability, appropriate food choices and physical access to fresh fruit and vegetables, particularly in low-income neighbourhoods. The HCP can play a central role in connecting families to community resources that enhance food security, such as public health departments, social work organization, faith-based organizations and community health services.

Box 2. Screening tool for identifying household food insecurity

Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more. Response: Yes or No

Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just did not last and we did not have money to get more. Response: Yes or No

Adapted from ref. (20). An affirmative response to both questions increases the likelihood of household food insecurity, however an affirmative response to 1 question often indicates household food insecurity and should prompt further inquiry (sensitivity 97%; specificity 83%).

Scholar

The HCP can enhance the integration of breastfeeding knowledge and HFI screening into medical education. The HCP can support interdisciplinary and participatory action research to strengthen evidence-based strategies to understand breastfeeding decision in HFI.

Health advocate

The HCP can strengthen advocacy at federal, provincial, and local governments levels to: (1) enhance programs that support breastfeeding and promote the World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) ‘Baby Friendly Initiative’, (2) ensure that infant feeding and food security policies are inclusive of breastfeeding promotion and (3) urgently prioritize a basic income guarantee for families.

LIMITATIONS

Our commentary has several limitations. Firstly, breastfeeding and HFI are inextricably linked to social and environmental factors, most strongly that of poverty and low family income. Isolating the effect of breastfeeding on HFI is challenging. Secondly, current research is limited and performed in the USA where breastfeeding barriers and HFI may be different than in Canada. Finally, poverty, low-income and vulnerable populations, such as people with mental health conditions, immigrants, those who are homeless, First Nations or living in remote communities, face cumulative comorbidities that may influence the association of breastfeeding and HFI.

CONCLUSION

A strong relationship exists between household food insecurity and poor child health outcomes. Breastfeeding provides ideal nutrition and food security for infants. However, a breastfeeding paradox exists. Infants of low-income families who will benefit most from the health benefits of breast milk are least likely to breastfeed (6). The role of the HCP will be paramount to realizing solutions to HFI and breastfeeding practice. Understanding this critical link may provide opportunities to affect clinical practice, public policy and child health outcomes.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose from all identified authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Murtala Abdurrahman and Dr Sylvie Bergeron for their helpful comments and Jill Mather and Evelyn Vaccari for their research support.

Funding Sources: There are no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose from all identified authors.

References

- 1. Hertzman C. [Social inequalities in health, early child development and biological embedding]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2013;61Suppl 2:S39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frank L. The breastfeeding paradox: A critique of policy related to infant food insecurity in Canada. Food, Culture & Society 2015;18:107–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jackson DB. The Association Between Breastfeeding Duration and Attachment: A Genetically Informed Analysis. Breastfeeding Medicine 2016. <https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dylan_Jackson/publication/301937556_The_Association_Between_Breastfeeding_Duration_and_Attachment_A_Genetically_Informed_Analysis/links/57b938e608aec9984ff3ca85.pdf> (Accessed August 4, 2016).

- 4. World Health Organization. 55th World Health Assembly. Agenda Item 13.10: Infant and Young Child Nutrition 2002. (cited May 18, 2002). <http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/WHA55.25_iycn_en.pdf>.

- 5. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. ; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murphy E, Parker S, Phipps C. Motherhood, morality, and infant feeding. In: Germov J, Williams L. (eds). Sociology of Food and Nutrition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999:242–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Health Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004): Income-Related Household Food Security in Canada 2007. (cited January 7, 2008). <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/surveill/nutrition/commun/income_food_sec-sec_alim-eng.php>.

- 8. Cook JT, Black M, Chilton M, et al. Are food insecurity’s health impacts underestimated in the U.S. Population? Marginal food security also predicts adverse health outcomes in young U.S. Children and mothers. Adv Nutr 2013;4:51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarasuk VMA, Dachner N. Household Food Insecurity in Canada 2014 2014. (cited April 5, 2016). <http://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Household-Food-Insecurity-in-Canada-2014.pdf>.

- 10. Health Canada. Household Food Insecurity in Canada: Overview (cited July 25, 2012). <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/surveill/nutrition/commun/insecurit/index- eng.php>.

- 11. Fazalullasha F, Taras J, Morinis J, et al. From office tools to community supports: The need for infrastructure to address the social determinants of health in paediatric practice. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19:195–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Canadian Paediatric Society. Are We Doing Enough? A Status Report on Canadian Public Policy and Child and Youth Health 2016. <http://www.cps.ca/uploads/status-report/sr16-en.pdf> (Accessed June 15, 2016).

- 14. Frank L. Exploring infant feeding pratices in food insecure households: What is the real issue? Food and Foodways 2015;23:186–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman AH, Racine AD, Messito MJ. Food insecurity and obesogenic maternal infant feeding styles and practices in low-income families. Pediatrics 2012;130:254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown LS, Colchamiro R, Edelstein S, Metallinos-Katsaras E. Effect of prenatal and postpartum food security status on breastfeeding initiation and duration in Massachusetts WIC participants 2001–2009. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27:1054.13. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zubieta AC, Melgar-Quinonez H, Taylor C. Breastfeeding practices in US households by food security status. The FASEB Journal 2006;20:A1004–A5. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orr SK, Tarasuk V. Breastfeeding and maternal physical and mental health among food insecure families with infants in Canada. The FASEB Journal 2016;30(1 Supplement):lb435–lb. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith JP, McIntyre E, Craig L, Javanparast S, Strazdins L, Mortensen K. Workplace support, breastfeeding and health. Family Matters 2013;19:58. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics 2010;126:e26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ke J, Ford-Jones EL. Food insecurity and hunger: A review of the effects on children's health and behaviour. Paediatrics & Child Health 2015;20:89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization & UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care, 2009. 2012. <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43593/1/9789241594967_eng.pdf>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]