Abstract

Introduction

In June 2012, the government of Canada severely restricted the scope of the Interim Federal Health Program that had hitherto provided coverage for the health care needs of refugee claimants. The Quebec government decided to supplement coverage via the provincial health program. Despite this, we hypothesized that refugee claimant children in Montreal would continue to experience significant difficulties in accessing basic health care.

Objectives

(1) Report the narrative experiences of refugee claimant families who were denied health care services in Montreal following June 2012, (2) describe the predominant barriers to accessing health care services and understanding their impact using thematic analysis and (3) derive concrete recommendations for child health care providers to improve access to care for refugee claimant children.

Methods

Eleven parents recruited from two sites in Montreal participated in semi-structured interviews designed to elicit a narrative account of their experiences seeking health care. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded using NVivo software and subjected to thematic analysis.

Results

Thematic analysis of the data revealed five themes concerning barriers to health care access: lack of continuous health coverage, health care administrators/providers’ lack of understanding of Interim Federal Health Program coverage, refusal of services or fees charged, refugee claimants’ lack of understanding about health care rights and services and language barriers, and four themes concerning the impact of denial of care episodes: potential for adverse health outcomes, psychological distress, financial burden and social stigma.

Conclusion

We propose eight action points for advocacy by Canadian paediatricians to improve access to health care for refugee claimant children in their communities and institutions.

Keywords: Refugees, Asylum seeker, Access to health care, Children

In 1957, the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) was created, providing refugees and refugee claimants with temporary health care coverage comparable to that of Canadian citizens on social assistance. Refugee claimants are individuals who make a claim for refugee status after arriving in Canada, and who undergo a judicial process to determine if they will be granted said status.

On June 30, 2012, the Canadian government drastically restricted the scope of the IFHP, dividing the refugee population into multiple categories according to migratory status and country of origin, each with different, limited coverage. For almost all groups, coverage of medication was eliminated except for diseases threatening public health or safety. For certain groups, coverage of medical services was eliminated unless they presented a risk for public health or safety. This initiative was vehemently opposed nation-wide by many medical associations, including the Canadian Medical Association (1). The IFHP cuts were reversed on April 1, 2016.

During the time of limited IFHP, the Quebec government supplemented health care coverage for refugee claimants. Ontario implemented a similar program in January 2014. Manitoba covered medications for privately sponsored refugees. Certain other provinces adopted more limited measures such as increased funding for refugee clinics. However, Quebec was the only province to institute comprehensive compensatory coverage of medical services and medications for all refugee claimants as soon as the IFHP cuts took effect in June 2012. Unfortunately, confusion abounded among health care providers and patients regarding who was covered and to what extent (2,3).

Our study sought to describe the experiences of refugee claimant children who were denied health services after June 2012, identify barriers to health care access and understand their impact. We anticipated that despite the Quebec government extending health care coverage, refugee claimant families faced difficulties in accessing care. We aimed to derive recommendations for health care providers in Canada to improve access to health care for paediatric refugee claimants.

METHODS

Overview

We conducted a qualitative study using in-depth semi-structured interviews to describe denial of care incidents among paediatric refugee claimants in Montreal, Quebec. This was a sub-study of a multi-site CIHR-funded project documenting accessibility and costs of health care for refugee claimants following changes to the IFHP (MOP-130451). We obtained ethics approval from the Centre de Services de Santé et des Services Sociaux (CSSS) de la Montagne and McGill University Health Centre review boards.

Participants

Between December 2014 and July 2015, we recruited families obtaining services from the Multicultural Clinic at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, a hospital-based clinic for children new to Canada, and two community-based clinics from within the CSSS de la Montagne (including the regional resettlement agency) that provide care to a large population of child and adult refugee claimants in the greater Montreal area. Patients were recruited through letters, advertisements and word-of-mouth. Using purposive sampling with the aim of including patients from each of the three clinics and from various countries of origin, we selected caregivers aged ≥18 years who reported that their child was denied health care services after June 2012 as a refugee claimant. Eligibility was verified at first phone contact with the participant, and again at the time of the interview. Recruitment proceeded until data saturation was reached.

Interviews

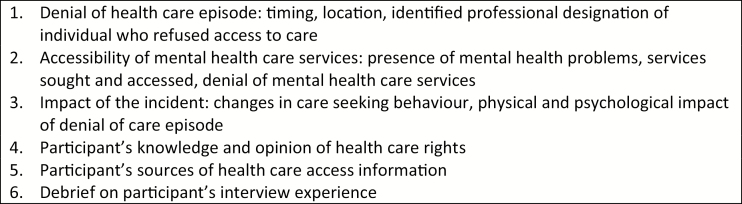

Interviews were conducted by N.R., F.M. and L.C. in French or English with interpreters facilitating interviews as needed in Arabic and Spanish. We obtained written informed consent and collected basic demographic data including participant age, country of origin and status of refugee claim. The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions to elicit a narrative account of participants’ experiences seeking health services (Figure 1). The interviewer took notes during the audio-recorded sessions. Interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes. Families received public transportation tickets and grocery store gift cards as compensation for their time.

Figure 1.

Semi-structured interview guide

Analysis

De-identified transcribed data were imported into NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Version 10), coded and subjected to thematic analysis. N.K. and F.M. generated the coding scheme with broad categories that were then refined through the review process.

RESULTS

We interviewed 11 parents (9 mothers, 2 fathers). The median ages were 33 years for parents (range 18 to 48 years) and 3.75 years for their children (range 3 months to 11 years). The families came from around the world (Caribbean, Africa, Middle East, Southeast Asia, South America) with a median time in Canada of 3 years (range 1 to 8 years). Pseudonyms have been employed throughout to preserve participant anonymity. Thematic analysis of the data revealed that (1) multiple barriers exist in child refugee claimants’ access to health care in Montreal, (2) lack of health care access negatively impacts children and families and engenders potential for adverse health events, (3) individual care providers and institutions may contribute to improving child refugee claimants’ care and (4) refugee claimants perceive that health care is a basic need for all children.

Barriers to health care access

Five themes describing barriers to health care access are illustrated in Table 1 through case vignettes and participant quotes.

Table 1.

Barriers to health care access

| Barriers to health care access | Case vignette | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of continuous health care coverage with IFHP | Mariam, mother of two from North Africa, recounts a denial episode after applying for IFHP renewal. | [Translation] ‘…my daughter got sick while we were waiting to receive the paper. She had fever and so on. She [the receptionist at the clinic] told me: ‘No, your paper is expired, we cannot see you.’ |

| Chris, the father of Kimani, brought his son to Canada so that they could join Kimani’s mother, an accepted refugee claimant. Kimani became sick while waiting for his initial IFHP documents, which took several weeks to arrive. His family was unable to pay the fees of a walk-in clinic. | ‘They couldn’t see the children because they don’t have Medicare (yet)’ | |

| Health care administrators/ providers’ lack of understanding of IFHP coverage | Helen’s son Anthony was referred to a respirologist for his recurrent pneumonias. She was asked to pay for the specialist visit and was told by the receptionist that she would be reimbursed by the provincial health coverage plan (RAMQ). | ‘They told me “You can call RAMQ, they’ll give you back the money” and it’s not true… I spent it and they don’t give me back the money.’ |

| Mariam from Africa recounts how a walk-in clinic close to her house only accepts refugees with urgent or public health problems. Unless Mariam paid, they would not accept to see her 2-year-old daughter Esra for fever that had been going on for 2 weeks because they considered it a chronic problem. | [Translation] ‘There (at the clinic), it’s for an infectious disease… or a very severe illness that they will see you. But if it is for a consultation just like that, they will not see you.’ | |

| Refusal of services or fees charged | Paola recounts through an interpreter her difficulties in consulting a physician for her school-aged daughter’s allergies, cough and fever. | [Translation] ‘We were told that where we showed up at the CLSC [local community health centre], we did not have the right, that there would be other places to receive health care but not here.’ |

| Upon her insistence and ability to advocate for her child, her daughter was finally given medical attention. | [Translation] ‘It took lots and lots of effort, talking with many different people and almost threatening them that ‘we will not leave if you do not take care of my daughter’ because they were refusing to see her and I had shown the paper.’ | |

| Refugee claimant’s lack of information about health care rights and services | When asked whether anyone had taught her about her families’ rights to see a doctor, a Southeast Asian mother replies: | ‘No, I don’t know (...) Sometimes I check the internet but I can’t understand.’ |

| One father describes an incident in which his daughter is brought to the emergency department, only to be turned away because the IFHP document was not brought with her. | ‘We didn’t know that each time we go to the hospital, to bring the big brown (IFHP) paper and present it (…). We had to go back home to get the (IFHP) paper, and all that’ | |

| Language barriers | An Anglophone mother brings her son Philip to the nearest hospital for his severe migraines but does not speak any French. Eventually, she leaves because she is not able to navigate the emergency department. She recounts: | ‘I didn’t see the doctor because I was there sitting and I couldn’t understand what they’re saying on the microphone or the nurses or anything. So then I left ‘cause it was just chaos in my head, I couldn’t understand what was goin’ on?’ |

| Basma, a mother from South East Asia struggles to understand the directives of a clinic receptionist to make an appointment. | ‘I don’t know because I can’t understand… I’m going here and there. First language problem. French I don’t know. English a little bit.’ |

IFHP Interim Federal Health Program

Lack of continuous health insurance with the IFHP

Denial of care occurred for children due to IFHP expiry or delays in receiving the initial or renewed documents (n=4). Families reported being unaware of their document expiry and difficulty accessing and understanding online instructions for renewal.

Health care administrator and provider lack of understanding of IFHP coverage

Participants reported that some administrators and/or physicians were misinformed or unsure about IFHP coverage. They also seemed unaware of the provincial coverage available to refugee claimants during the period of IFHP cuts. Some were told that only urgent problems or those posing a public health risk were covered. Others were told that the IFHP would reimburse the claimant directly for fees paid (n=3). However, the IFHP only reimburses providers, not claimants directly (4).

Refusal of services or fees charged to refugee claimants

All interviewees were at some point refused services for their children or asked to pay for clinic consultations, hospital visits, medications or investigations. Many parents describe the inability to pay the fees (n=7). As a result, they were not seen by the physician (n=4) or did not purchase prescribed medication (n=3). Other families paid the fees for clinic visits (n=4) and paid for their child’s medication (n=7), despite reporting financial strain.

Lack of information regarding health care rights and services

Most of the participants received no or very sparse information from Citizenship and Immigration Canada about their health care rights and how to access health services. Knowledge was primarily acquired by word-of-mouth and social worker assistance. Some families held erroneous beliefs about their rights to access being restricted to urgent care only, based on experiences of denial of care (n=2).

Language barriers

Some participants struggled to navigate the health care system because their French and/or English was limited.

The negative impact of lack of access to health care

Four themes describing the impact of denial of care episodes were identified, as illustrated in Table 2 through case vignettes and quotes.

Table 2.

The negative impact of lack of access to care

| Negative impact of lack of access to care | Case vignettes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Potential for adverse health outcomes | Fatima, who immigrated from West Africa, tries to consult a clinic with her daughter Issa, who is known for difficult-to-treat constipation. | [Translation] ‘...For our little daughter who has a bad case of constipation. Once she almost had an intestinal blockage. So I went … there (to a clinic)… she was sick and they told me no straight out … (in the end) they hospitalized us for 13 days.’ |

| Mariam is on welfare. Her 5-year-old son Ali has advanced caries with a dental abscess. At one point, she was told that dental services were not covered for refugee children anymore. | [Translation] ‘Me... [and my son] do not have the right to have dental care and I do not have the money, that is why I only get one filling [for him] done every 6 month, just until [I] have collected more money’ | |

| Psychological distress | Mariam endures stress when taking her 5- year-old son Ali to the hospital. | [Translation] ‘Every time we go to the hospital, it’s stress, because I wait, I bring my son, and in the last minute we have a negative answer: “You cannot have access to this service because you are not covered.”’ |

| Paola struggles to have her 11-year-old daughter Dalia seen in a clinic for her allergies. | [Translation] ‘Certainly at that very moment there is a lot of stress because there is nothing I can do. We do not have the money to go to a private clinic. If we get refused, it creates stress.’ | |

| Financial burden | Cynthia, a single mother in her mid-thirties from the Caribbean, was charged for an emergency ophthalmology consultation for her son Philip. | ‘I broke down in tears ‘cause […] his eyes […] he couldn’t see, his eyes was getting so bad that I end up and paid the 120 $. I wanted that money so bad to pay the rent.’ |

| Social stigma | Fatima, mother of Issa and Amina, returns to the same optometrist where her daughters had been seen free of charge for her glasses before the 2012 cuts. She is now asked to pay and tells us how the receptionist got very agitated upon her questioning about the reason. | [Translation] ‘That day I was very frustrated, I felt humiliated in my dignity.’ |

| Cynthia and other friends who are refugees feel stigmatized about using the IFHP document. | ‘A lot of people are ashamed to use this paper.’ | |

| Mariam is waiting to see a doctor for her daughter in a local clinic. When she is finally turned away at the desk, she lies to other parents in the waiting room, stating that her own doctor was not available that day and that she would return another time. | [Translation] ‘I was embarrassed. I didn’t want to tell her “Because we don’t have papers like you do, we’re not covered.” I was embarrassed, I left. I couldn’t go home. I walked and walked and walked. My daughter said “Mummy, I’m tired.” “I didn’t even know what I was going to do.”’ |

IFHP Interim Federal Health Program

Potential for adverse health outcomes

No parent reported a significant adverse health outcome. However, delays in seeking or receiving care for children suffering from severe constipation, dental abscess, acute asthma, seizure or prolonged fever caused significant distress and, in some cases, could have been life-threatening. After experiencing denial of care, several parents reported avoiding seeking medical care unless their child became severely ill.

Psychological distress

Families reported stress related to their refugee status and processing of their claim, the uncertainty of their future, difficulties in finding a job, inability to access childcare and language barriers. Episodes of denial of care were described as a source of additional significant stress (n=5).

Financial burden

Though the interview was not designed to address families’ financial status, parents spontaneously mentioned their financial struggles and dependence on social assistance (n=6). When fees were charged for medications or a medical consultation, those who paid were required to sacrifice other basic needs (paying rent, purchasing groceries), sell their possessions, borrow money from friends or accept anonymous donations.

Social stigma

Some refugee claimants expressed feeling stigmatized by the distinct identification and registration process required to access health care in hospitals and clinics (n=5).

Individual institutions and health care providers can do their part

Given that participants were recruited from medical clinics where they ultimately received care, many claimants also had positive experiences with the health care system. They received help from physicians, pharmacists and social workers, and became familiar with clinics and institutions that were amenable to caring for refugee claimants. Several made use of non-governmental organizations that provided free prenatal care, mental health care and social services.

A child’s need for care

Every parent interviewed identified health care as a basic need. Along with many other participants, one mother expressed that while she could delay medical consultation for herself, she could not do so for a child.

[Translation] ‘But it’s very difficult when my children are affected. I thought if I can get in here, I know this country gives a lot of protection to children. At least when we get in I prefer at least they give health cards to the children of refugees, because for us whatever happens to our children affects our dignity… Sometimes we can accept bad things, but not bad things happening to our children.’

Several participants described health care services for children as a basic human right. Paola, a South American mother who suffered psychological distress when her child’s health care resulted in a costly and unaffordable bill, highlighted this as an important message to convey to the government:

[Translation] ‘… tell the government that refugees should have the same rights as others for access to health care services and that we shouldn’t have to fight for the minimum.’

DISCUSSION

Quebec is one of the few Canadian provinces that immediately supplemented health care services cut from the IFHP in June 2012. All refugee claimant children in this study should have been eligible for health care services. Despite this, our results show that difficulties in accessing care persisted in Montreal. The barriers we identified mainly related to administrative hurdles and lack of provider and refugee claimant knowledge regarding the IFHP. Denial of care resulted in the potential for adverse health outcomes and significant psychosocial distress. However, study participants also reported positive experiences with various individuals and institutions that ultimately provided them health care.

Few studies have documented the experiences and outcomes of refugee claimant children and their families following the IFHP cuts. The Wellesley Institute produced two reports exposing the negative impact of the cuts from the health care provider’s perspective, based on qualitative interviews and an online survey developed by Canadian Doctors for Refugee Care. These reports highlighted the following sequelae: (1) negative health outcomes pertaining to lack of drug coverage, (2) reduced health care access, especially for primary care and chronic disease management, (3) avoidable emergency room visits, (4) increased administrative complexity and (5) risks to vulnerable populations including pregnant women and children (2,6). A study at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto demonstrated that the number of emergency visits was significantly decreased while hospital admission rates increased (not significantly) for refugee claimants covered by the IFHP following the cuts. Although the interpretation of these results was limited by the study design, they may reflect important changes in health care access (7).

Our study adds to existing literature suggesting that eligibility for IFHP does not consistently translate to health care access. Prior to the IFHP funding cuts, a study conducted in Toronto and Montreal documented denial of health care to IFHP-insured mothers and their infants (10). As demonstrated through online surveys of health care providers, the 2012 IFHP changes further complicated an already poorly understood process in Quebec and Canada (2,3,6).

The narratives of our study participants highlight opportunities to increase health care accessibility and resolve the difficulties encountered by refugee claimant children and their families. Just as the refugee claimants in the current study, several institutions in Canada recognize health care as a fundamental human right. Accordingly, these institutions have adopted a policy of no denial (7,8). The Liberal government has also followed through on its pledge to fully restore the IFHP (9). The need to renew IFHP documents for refugee claimants whose certificate was issued or expired after April 10, 2016 has also been eliminated. However, refugees who are awaiting their initial certificate or whose coverage expired prior to April 10th may still experience lack of coverage. Access problems are likely to persist unless health care providers and administrators actively seek to make access a reality. Health care providers can sign up for and improve their knowledge of IFHP (4,11–13), as well as that of their trainees and administrative staff, because many of the refugee claimants interviewed were denied access by non-physician members of the health care team.

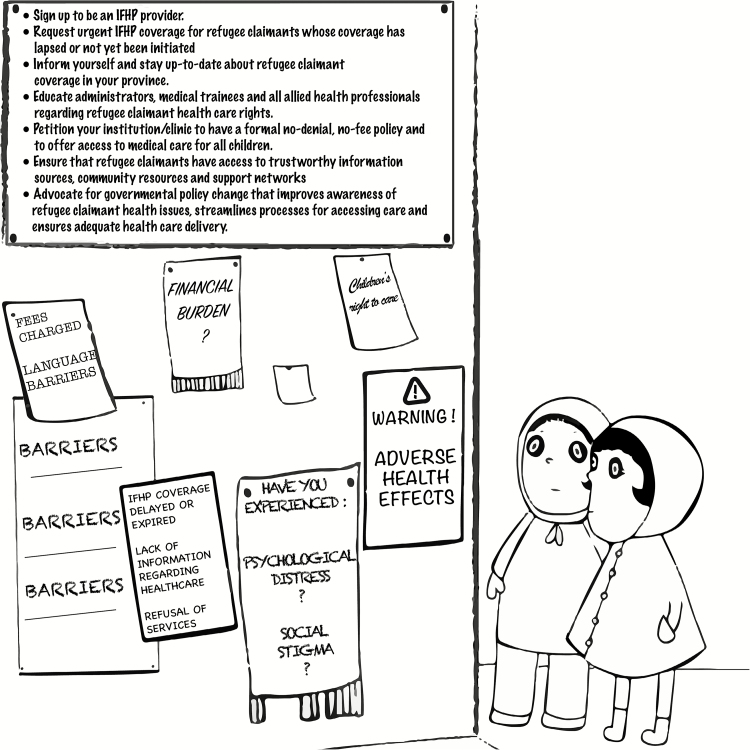

Paediatricians can make use of the CPS recommendations regarding advocacy for immigrant and refugee health needs to address barriers to care (14). We developed potential action points for Canadian paediatricians, based on the themes identified in our study (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Action points for paediatricians to ensure health care insurance and access to refugee claimant children and their families

Paediatricians can petition their institution/clinic to have a formal no-denial, no-fee policy and to offer access to medical care for all children.

Paediatricians can request urgent IFHP coverage for refugee claimants whose coverage expired before April 10, 2016 or who have not yet received their IFHP certificate.

Paediatricians can sign up to be an IFHP provider.

Paediatricians can inform themselves and stay up-to-date about refugee claimant coverage in their province.

Paediatricians can educate administrators, medical trainees and all allied health professionals regarding refugee claimant health care rights.

Paediatricians can ensure that refugee claimants they encounter have access to trustworthy information sources, community resources and support networks.

Paediatricians can advocate for governmental policy changes that improve awareness of refugee claimant health issues, streamline processes for accessing care and ensure adequate health care delivery.

Limitations

Despite our small sample size, data saturation was achieved in our thematic analysis, suggesting that more interviews may not have contributed additional major themes. Selection bias was inherent to the recruitment strategy in that our sample ultimately received care—we do not report the experiences of families who were denied care and never received it. Thus, potential adverse outcomes may have been underestimated in our sample.

CONCLUSION

Although Canada has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, our study adds to existing literature suggesting that we are failing to ‘strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to […] health care services’ (15). The administrative procedures for refugee claimants to obtain valid health care coverage and for physicians to deliver it are marred with obstacles. This places vulnerable families and their children at risk of denial of health care services, delay in seeking and accessing care and lack of preventive services, entailing potential for adverse outcomes. As paediatricians and concerned citizens, we have a critical role in both providing health care services and advocating for changes to existing government policies that create such unnecessary barriers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

P.L. reports salary support from Fonds de la Recherche du Québec–Santé, salary support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research and grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, during the conduct of the study.

Acknowledgements

Fiona Muttalib and Nikki Rink are both first co-authors on this study. The authors would like to acknowledge the important contributions of Dr. Louise Auger and Dr. Claudette Bardin to this study, and Emilie Carbonneau for the design of the graphics in Figure 2.

Funding Sources: This was a sub-study of a multi-site CIHR-funded project documenting accessibility and costs of health care for refugee claimants following changes to the IFHP (MOP-130451). P.L. received salary support from the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec – Santé and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

References

- 1. Canadian Medical Association. Letter to Minister Kenney 2012. <www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Publications/News_Releases/News_Items/kenney vers3 - may2012.pdf>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 2. Barnes S. The Real Cost of Cutting The Interim Federal Health Program The Wellesley Institute, October, 2013. <www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Actual-Health-Impacts-of-IFHP.pdf>. (Accessed August 14, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruiz-Casares M, Cleveland J, Oulhote Y, Dunkley-Hickin C, Rousseau C. Knowledge of healthcare coverage for refugee claimants: Results from a survey of health service providers in Montreal. PLoS ONE 2016;11(1):e0146798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Citizenship and Immigration Canada GoC, Medavie Blue Cross. Interim Federal Health Program: Information Handbook for Healthcare Professionals <https://docs.medaviebc.ca/providers/guides_info/IFHP-Information-Handbook-for-Health-care-Professionals-April-1-2016.pdf>. (Accessed August 14,2017).

- 5. Holcroft C. Pressure Building on Federal Government to Reverse Course on Refugee Health Cuts as Parliament Set to Return 2013. <www.doctorsforrefugeecare.ca/index.html>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 6. Marwah S. Refugee Health Care Cuts in Canada: System Level Costs, Risks and Responses The Wellesley Institute, February 2014. <www.wellesleyinstitute.com/publications/refugee-health-care-cuts-in-canada-system-level-costs-risks-and-responses/>. (Accessed August 14, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evans A, Caudarella A, Ratnapalan S, Chan K. The cost and impact of the interim federal health program cuts on child refugees in Canada. PLoS ONE 2014;9(5):e96902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Council for Refugees. Refugee Health Survey by Province and by Category. February 2015. <http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/ccr-refugee-health-survey-public.pdf>. (Accessed August 14, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Liberal Party of Canada. A New Plan for Canadian Immigration and Economic Opportunity [PDF] [cited December 12, 2015]. Liberal Party Platform 2015. <www.liberal.ca/realchange/refugees/>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 10. Merry LA, Gagnon AJ, Kalim N, Bouris SS. Refugee claimant women and barriers to health and social services post-birth. Can J Public Health 2011;102(4):286–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Medavie Blue Cross. IFHP Provider Portal. <http://web.medavie.bluecross.ca/en/health-professionals/resources>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 12. IFHP Provider Application Form. <http://web.medavie.bluecross.ca/en/health-professionals/register>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 13. Citizenship and Immigration Canada GoC. Interim Federal Health Program: Summary of Benefits [cited November 26, 2015]. 2015. <www.cic.gc.ca/english/refugees/outside/summary-ifhp.asp>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 14. Canadian Paediatric Society. Advocacy for Immigrant and Refugee Health Needs 2015. <http://www.kidsnewtocanada.ca/beyond/advocacy>. (Accessed August 14, 2017).

- 15. United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989. Ann Rev Popul Law 1989;16:95, 485–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]