CASE PRESENTATION

A previously healthy 7-month-old female presented to hospital with multiple raised red papules (3 mm in size) on her left anterior chest, below the clavicle (Figure 1). The lesions were not painful or pruritic, and she was systemically well until later in the evening on the day of presentation when she developed a disseminated maculopapular rash and a low-grade fever.

Figure 1.

Papular lesions on the left anterior chest following travel to Mississippi and Tennessee

She resided in Ontario, with notable travel to Hernando, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee for 10 days approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. While travelling she spent most of the time indoors. She had not traveled elsewhere in the year prior to presentation. She was continuing to breast feed, and had recently begun taking pureed food. There were no sick contacts, or animal exposures.

She was seen in a local emergency department and diagnosed with a viral exanthem. She returned to the same emergency department the following day due to persistent fever. She was hospitalized for suspected dehydration. Complete blood count, liver enzymes, renal function and serum electrolytes were within normal limits. PCR of a lesion swab tested negative for varicella zoster virus.

Within 24 hours of admission, the fever and generalized maculopapular rash resolved. However, the papular lesions on her upper anterior chest persisted. The mother applied breast milk to the papules and within seconds noticed small white thread like objects protruding briefly from the centre of a few of the papules. This was repeated by the nursing staff when sucrose fluid was applied to the papules.

A clinical diagnosis was made and treatment instituted.

DISCUSSION

On close examination of the papules, a single small central pore was noted in each lesion. With the application of Vaseline to each lesion, a thread-like object began protruding through the central pore. This observation is pathognomic for cutaneous myiasis.

Cutaneous myiasis is usually caused by Dermatobia hominis (the human botfly) in the Americas, or Cordylobia anthropophaga (Tumbu fly) in Africa, though many fly species may infest the flesh of humans and animals. The human botfly lays eggs on the underside of blood-feeding insects which then deposit the eggs on the host’s skin (human or livestock) at the time of a blood meal (1). Other species endemic to North America, such as Cuterebra spp., lay their eggs on vegetation with human infection following direct contact with the plant. The Tumbu fly lays eggs on moist clothing put out to dry, coming in contact with the host’s skin when the clothing is worn, translating into predominant lesions in the waistband area, wrists and ankles. Upon hatching, fly larvae penetrate the dermis and burrow into the sub-dermal layer, leaving a breathing hole which often appears as a small black punctum. When this hole is occluded by a liquid or soft substance, such as petroleum jelly, the maggot will typically emerge partially from the hole, enabling definitive diagnosis. When a slab of meat is applied over the punctum, the larva will often burrow into the meat allowing for easy identification and extraction.

The epidemiology of cutaneous myiasis in North America was previously considered to be limited to the southern United States or tropical regions (2). However, 52 cases of furuncular myiasis have been reported in Canada, 8 of which were Cuterebra spp. acquired locally (1). Our patient likely acquired her myiasis during travel to the Southern United States rather than locally.

Our infant’s systemic symptoms (fever and maculopapular rash) were likely unrelated to the presentation and likely contributed to a delay in diagnosis. In older children and adults, a creeping sensation within the lesions can serve as a diagnostic clue. Lesions may be painless due to the local anesthetic effect of the larvae’s secretions. Painless emergence of an immature or mature larva from the lesion can also occur.

Extraction of the larvae by applying lateral physical pressure or less commonly vacuum extraction using a commercial venom extractor is a common treatment method as larvae maturation can be painful or rarely, associated with secondary soft tissue bacterial infection (3). For larvae in later stages of development, surgical excision has been used. Occlusion of the air-hole, for example by applying Vaseline in a pill bottle cap taped to the skin for several hours, is an option if extraction is not feasible or successful, in which case the larvae suffocate and resorb over time.

In our case, an occlusive petroleum jelly dressing was applied after an attempt at worm extraction was unsuccessful. When seen in follow-up, the lesions were greatly reduced in size and had no signs of secondary infection. Although very rare, the family was counselled to watch for signs of infection including purulent drainage, surrounding erythema and pain. Within days, a furuncle formed over one of the lesions and spontaneously drained. A small thread-like maggot was isolated and sent to the Public Health Ontario Laboratory for parasitic identification, which confirmed infection with D. hominis (Figure 2).

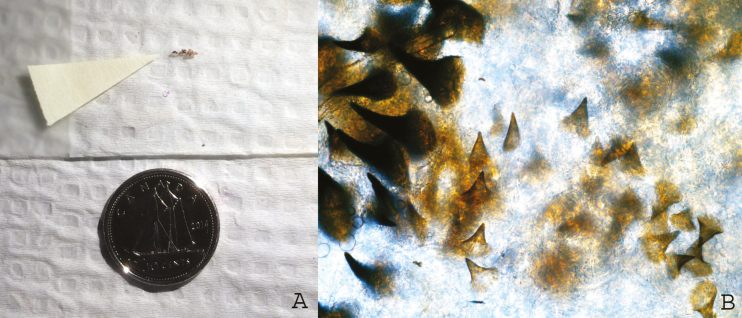

Figure 2.

(A) Gross appearance of an immature Dermatobia hominis larva extracted from a punctate papule on the anterior chest of a 7-month-old traveler to Mississippi and Tennessee. (B) 400× magnification of radial spines of the immature D. hominis larva

CLINICAL PEARLS

Clinical clues to the diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis due to Dermatobia hominis include an intermittent creeping sensation within the lesion, and presence of a central pore that appears like a black punctum and partial emergence of the larvae after applying petroleum jelly (or another occlusive liquid or substance).

Cutaneous myiasis can be acquired both locally and with travel and does not necessarily require significant outdoor exposure.

Simple extraction is the treatment of choice, but if too difficult, occlusion of the pores is also effective. Extracted maggots can be submitted for identification to the local Public Health Laboratory in alcohol or formaldehyde for preservation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Filip Ralevski and Jason Gasgas for assistance with images.

References

- 1. Macfadden DR, Waller B, Wizen G, Boggild AK. Imported and locally acquired human myiasis in Canada: A report of two cases. CMAJ 2015;187:272–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sherman RA. Wound myiasis in urban and suburban United States. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2004–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boggild AK, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Furuncular myiasis: A simple and rapid method for extraction of intact dermatobia hominis larvae. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:336–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]