Abstract

Background

The SQ house dust mite (HDM) SLIT-tablet (ALK, Denmark) addresses the underlying cause of HDM respiratory allergic disease, and a clinical effect has been demonstrated for both HDM allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma. Here, we present pooled safety data from an adult population with HDM respiratory allergy, with particular focus on the impact of asthma on the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet tolerability profile.

Methods

Safety data from 2 randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials were included: MT-04: 834 adults with HDM allergic asthma not well controlled by inhaled corticosteroids and with HDM allergic rhinitis, and MT-06: 992 adults with moderate-to-severe HDM allergic rhinitis despite the use of allergy pharmacotherapy and with or without asthma.

Results

The proportion of subjects experiencing adverse events (AEs) was greater in the active treatment group (12 SQ-HDM; 73% of subjects) compared to placebo (53%). The most common treatment-related AEs were local allergic reactions. No AEs were reported as systemic allergic reactions. Regardless of asthma status, most AEs were mild or moderate (>97% of AEs) and the frequency of serious AEs was low. Subgroup analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the risk of experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs for subjects with asthma compared to subjects without asthma (p = 0.88). In addition, subjects with partly controlled or uncontrolled asthma were no more likely to experience moderate or severe treatment-related AEs than subjects with controlled asthma (p = 0.42).

Conclusion

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is well tolerated, and the safety profile was comparable for subjects with HDM respiratory allergic disease irrespective of asthma status.

Keywords: House dust mite, Allergy immunotherapy, SLIT-tablet, Allergic asthma, Allergic rhinitis, Safety

Introduction

House dust mite (HDM) respiratory allergic disease has 2 main clinical manifestations: allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma [1]. The vast majority of patients with HDM respiratory allergy suffer from allergic rhinitis and almost half have concomitant allergic asthma [2]. Many patients have persistent symptoms all year [3, 4].

In addition to allergy immunotherapy (AIT), current treatment options for HDM respiratory allergic disease include allergen avoidance and allergy pharmacotherapy. However, allergen avoidance is often not sufficient, and studies suggest that a substantial proportion of patients experience inadequate symptomatic control by allergy pharmacotherapy [5, 6, 7]. The AIT treatment effect is generally well established for allergic rhinitis [8], but the use of AIT in allergic asthma is not adequately documented due to a lack of well-designed clinical trials [9, 10].

Consequently, international asthma treatment guidelines have been reluctant to accept AIT as a treatment option for allergic asthma [11]. This reluctance is based on a notion that the available AIT efficacy evidence in allergic asthma is not sufficient for outweighing the risks of AIT, which have been considered to constitute a particular problem in patients with asthma [11]. Deaths have occurred with subcutaneously administered AIT (SCIT) and studies have reported an estimated incidence of fatal reactions in 1 of 2.5 million injections [12, 13]. Most fatal reactions (88%) involved asthmatic patients, and patients with not well-controlled asthma appeared to be at highest risk [13]. Thus, some national treatment guidelines consider uncontrolled and severe asthma to be contraindications for AIT [14, 15].

In the past decade, a number of well-powered clinical trials with sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) have been published, in particular with SLIT-tablets [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25], and 5 SLIT-tablet products (2 grass SLIT-tablets, 2 HDM SLIT-tablets, 1 ragweed SLIT-tablet) are now authorised for at-home treatment of allergic rhinitis in different regions of the world. As the only one, the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet is authorised for treatment of both HDM allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma in a number of countries in Europe and in Australia. While treatment initiation is contraindicated in patients with impaired lung function (FEV1 <70% of predicted value) and in patients who have experienced a severe asthma exacerbation within the last 3 months, the overall picture indicates a safety and tolerability profile of SLIT-tablets which is more benign than that of SCIT [26], on which the concerns regarding asthma were originally based. This is particularly relevant for HDM respiratory allergy patients, about half of whom have allergic asthma [2].

The safety and tolerability of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet were tested in 2 phase I trials [27], and subsequently clinical efficacy in both HDM allergic asthma and HDM allergic rhinitis has been demonstrated in 6 published randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy trials [22, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. The present study reports pooled safety and tolerability data from the 2 phase III trials that formed part of the basis for regulatory approval in several European countries and in Australia; the 2 trials covered a broad European population of adult patients with HDM respiratory allergy. Particular focus is on the impact of allergic asthma on the safety and tolerability profile of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. Data for the dose approved in Europe and Australia (12 SQ-HDM) are presented.

Materials and Methods

MT-04 and MT-06 were both randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials (EudraCT No. 2010-018621-19 and 2011-002277-38, respectively) (Table 1) designed and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, and its amendments and subsequent clarifications) [33] and Good Clinical Practice [34]. The primary objective of MT-04 was to demonstrate effective and tolerable treatment of HDM allergic asthma [24], while the primary objective of MT-06 was to demonstrate effective and tolerable treatment of HDM allergic rhinitis in adults with HDM respiratory allergic disease [25]. FEV1 <70% of predicted value after adequate pharmacological treatment at randomisation and a severe asthma exacerbation within the last 3 months prior to randomisation were exclusion criteria in both trials.

Table 1.

Overview of included trials with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet

| Trial | Treatment | Population | Rhinitis | Asthma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT-04 (phase III) EudraCT: 2010-018621-19 [24] | 6 or 12 SQ-HDM or placebo, 13–19 months of treatment | 834 adults | HDM allergic rhinitis, no requirements for severity or medication use | HDM allergic asthma not well controlled by ICS corresponding to the doses used at GINA medication steps 2–4 |

| MT-06 (phase III) EudraCT: 2011-002277-38 [25] | 6 or 12 SQ-HDM or placebo, 1 year of treatment | 992 adults | Moderate-to-severe HDM allergic rhinitis with a high level of symptoms and impaired quality of life despite frequent medication use | Mild asthma controlled by ICS (GINA medication steps 1–2) allowed but not required |

HDM, house dust mite; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma.

The SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (ALK, Denmark) is a rapidly dissolving freeze-dried tablet containing a 1:1 mixture of allergen extracts from the HDM species Dermatophagoidespteronyssinus and D. farinae. Source material of bodies and faeces makes certain the tablet contains the broadest possible spectrum of major and minor allergens from these HDM species. A highly standardised production process ensures a 1:1:1:1 ratio of the Der p 1, Der f 1, Der p 2, and Der f 2 major allergens [35].

Initial administration of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was performed under physician supervision followed by monitoring for at least 30 min. Pooled data from the 2 trials were used to describe the overall safety profile, most common treatment-related AEs (AEs assessed by the investigator as being related to the treatment), and severe treatment-related AEs. Pooled data were also used to describe the onset and duration of the most common treatment-related AEs. In addition, treatment-related serious adverse events (SAEs, i.e., life-threatening AEs or AEs that resulted in death, hospitalisation, congenital anomaly, disability, or permanent damage, or that required intervention to prevent permanent damage) were described. Further, the safety results were analysed to reveal differences in safety and tolerability that might arise from differences in severity of HDM allergic asthma.

All AEs observed by the investigators or reported by the subjects were recorded. Included in this pooled analysis are all AEs occurring after the first administration of treatment. Investigators assessed the seriousness, severity, and possible relationship to treatment (causality) for all AEs. AEs, including SAEs, were defined according to the ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline E2A [36] and coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). For further details on the recording and classification of AEs, please see the online supplementary material (www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000478699).

In the MT-04 trial, subjects' baseline asthma control was assessed by their Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score and subsequently, a pre-specified translation to Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) control criteria was performed [29, 31].

Results

Trial Population

A table of subject disposition pooled from the 2 trials is found in this article's online supplementary material (online suppl. Table S1). A total of 1,215 adult subjects were included in the analysis: 600 randomised to the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (dose 12 SQ-HDM) and 615 to placebo. The overall proportion of subjects who discontinued the trials was similar in both treatment groups (19% of subjects on active treatment and 18% on placebo). When looking specifically at trial discontinuations due to AEs, the proportion was greater among subjects on active treatment (6% of subjects) compared to placebo (2%).

Both trials were conducted in Europe; 52% of the trial population was male, and more than 99% of subjects were Caucasian. The mean age was 33 years (range 17–83 years). Approximately two-thirds of the subjects were sensitised to other airborne allergens in addition to HDM (e.g., pollen, mould, and dander). All 1,215 subjects had a clinical history of HDM allergic rhinitis, and 863 (71%) also had HDM allergic asthma. The average history of HDM allergic rhinitis was 12 years (median 9 years) and the average history of HDM allergic asthma was 12 years (median 8 years). In the MT-04 trial, in which all subjects were required to have HDM allergic asthma per trial inclusion criteria, the mean FEV1 at randomisation was 93% of the predicted value. In addition, the MT-04 trial population was required to have HDM allergic asthma which was not well-controlled by inhaled corticosteroids (ICS; mean daily ICS dose at randomisation was 588 µg budesonide), as defined by an ACQ score of 1–1.5 (mean ACQ score at randomisation was 1.23) [24]. In the MT-06 trial, in which subjects were only required to have HDM allergic rhinitis, 46% of subjects had mild HDM allergic asthma. Across both trials, mean FEV1 at randomisation was 98% of the predicted value.

Overall, in the pooled population, 559 subjects (46%; from the MT-04 trial) were classified as having uncontrolled or partially controlled asthma (according to GINA control criteria), as characterised by higher mean daily ICS use, higher daytime asthma symptom score, lower FEV1, more nocturnal awakenings, and higher short-acting β-agonist intake at randomisation. This subgroup with uncontrolled/partially controlled HDM allergic asthma was investigated specifically with regard to the safety profile.

Overall Safety Profile

Table 2 provides a summary of AEs reported in the 2 trials. The proportion of subjects experiencing AEs was greater in the active treatment group compared to placebo (73 vs. 53% of subjects, respectively). For AEs assessed as possibly related to treatment, this difference was even more pronounced, with 50% of subjects on active treatment reporting treatment-related AEs compared to 16% of subjects on placebo. A slightly larger proportion of subjects experienced AEs leading to trial discontinuation in the active treatment group (6%) compared to placebo (2%). Numbers were similar in both treatment groups with regard to the severity of AEs (distribution of mild, moderate, and severe AEs) and the frequency of SAEs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall AE summary for adult subjects in the 2 trials

| 12 SQ-HDM (n = 600) |

Placebo (n = 615) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %n | e | %e | n | %n | e | %e | |

| All AEs | 435 | 73 | 1,511 | 100 | 328 | 53 | 835 | 100 |

| Causality | ||||||||

| Possibly | 297 | 50 | 808 | 53 | 98 | 16 | 165 | 20 |

| Unlikely | 305 | 51 | 703 | 47 | 295 | 48 | 670 | 80 |

| Severity | ||||||||

| Mild | 365 | 61 | 1,055 | 70 | 256 | 42 | 550 | 66 |

| Moderate | 203 | 34 | 423 | 28 | 148 | 24 | 258 | 31 |

| Severe | 27 | 5 | 33 | 2 | 24 | 4 | 27 | 3 |

| Seriousness | ||||||||

| Serious | 7 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 19 | 3 | 20 | 2 |

| Not serious | 434 | 72 | 1,501 | 99 | 324 | 53 | 815 | 98 |

AE, adverse event; n, number of subjects with event; %n, percentage of subjects with event; e, number of events; %e, percentage of events.

Safety Profile in Subjects Based on Asthma Status

When comparing the overall safety data for subjects with and without asthma, a number of minor differences were observed, as specified in the following. Among subjects on active treatment, a greater proportion of subjects with asthma (75%) reported AEs compared to subjects without asthma (66%). However, fewer subjects with asthma (48%) reported treatment-related AEs compared to subjects without asthma (53%). Regardless of asthma status, the vast majority of reported AEs were mild or moderate (>97% of AEs in both subgroups) and the frequency of SAEs was low (3% of subjects with asthma experienced SAEs compared to 1% of subjects without asthma).

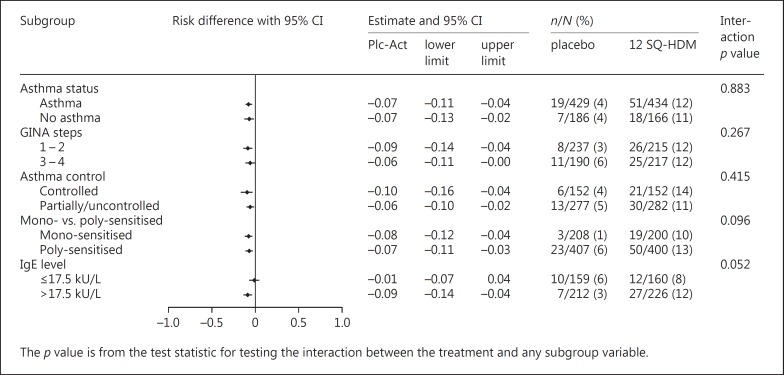

Specific subgroup analyses were conducted to reveal potential differences in the safety profile of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet based on subjects' asthma status. Figure 1 presents a forest plot of the differences between treatment groups in the proportion of subjects experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs in specific subgroups. As expected, based on the overall safety profile, more subjects on active treatment experienced treatment-related AEs compared to the placebo group. As presented in Figure 1, this was the case irrespective of asthma status. Subgroup analysis by asthma status revealed no statistically significant difference in the risk of experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs for subjects with asthma compared to subjects without asthma (Nasthma = 863, Nno asthma = 352; p = 0.88). Among subjects on active treatment, 12% with asthma and 11% without asthma reported events. Likewise, the proportion was 12% regardless of subjects' level of asthma medication (GINA step) at screening, and subgroup analysis based on GINA medication step at screening did not show any statistically significant impact (p = 0.27).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of differences in proportions of subjects with moderate or severe treatment-related adverse events in various subgroups (MT-04 + MT-06 full analysis set). GINA step subgroups include subjects based on level of asthma medication at screening. Mono-sensitised includes subjects sensitised to house dust mite (HDM) only; poly-sensitised includes subjects sensitised to allergens beyond HDM. Plc-Act, placebo-active.

When comparing subjects with uncontrolled or partially controlled asthma at treatment initiation (n = 559) to subjects with controlled asthma (n = 304), overall safety data revealed a greater proportion of subjects reporting AEs among subjects with partly or uncontrolled asthma (70% of subjects) compared to subjects with controlled asthma (57%). Similarly, more subjects with partly or uncontrolled asthma experienced severe AEs (6%) compared to subjects with controlled asthma (2%). In contrast, when looking specifically at AEs related to treatment, the proportion of subjects reporting events was similar for subjects with controlled asthma (52% on 12 SQ-HDM; 11% on placebo) compared to subjects with partly controlled or uncontrolled asthma (46% on 12 SQ-HDM; 17% on placebo). This was supported by specific subgroup analysis of the proportion of subjects experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs (Fig. 1), which showed that subjects with uncontrolled or partially controlled asthma were no more likely to experience moderate or severe treatment-related AEs than subjects with controlled asthma (11 and 14% of subjects on active treatment, respectively). Thus, the risk of experiencing treatment-related AEs was not influenced by asthma control (controlled vs. uncontrolled/partially controlled asthma, p = 0.42) (Fig. 1).

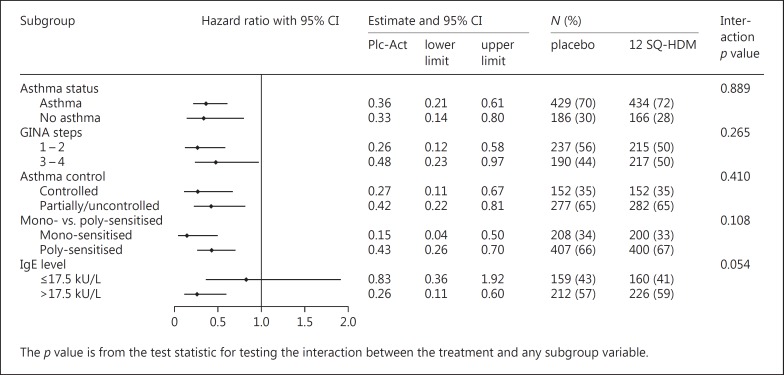

Figure 2 shows the risk of experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs over time, depicted as hazard ratios for the various subgroups. Across all subgroups, hazard ratios were less than 1, indicating an increased risk of treatment-related AEs in the active treatment group compared to placebo. No statistically significant differences were observed between subgroups (asthma vs. no asthma, p = 0.89; GINA step 1–2 vs. step 3–4, p = 0.27; controlled vs. uncontrolled/partially controlled asthma, p = 0.41).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of hazard ratio for subjects with moderate or severe treatment-related adverse events in various subgroups (MT-04 + MT-06 full analysis set). GINA step subgroups include subjects based on level of asthma medication at screening. Mono-sensitised includes subjects sensitised to house dust mite (HDM) only; poly-sensitised includes subjects sensitised to other allergens in addition to HDM. Plc-Act, placebo-active.

Safety Profile in Subjects Based on Sensitisation Status and Specific IgE Level

As presented in Figures 1 and 2, subgroup analyses based on subjects' sensitisation status revealed no significant differences in the risk of experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs between subjects only sensitised to HDM and subjects sensitised to additional allergens (p ≥ 0.1).

When comparing subjects based on serum levels of HDM-specific IgE, the overall proportion of subjects reporting AEs was similar regardless of IgE level (approx. 66%). However, a greater proportion of subjects with high HDM-specific IgE levels (>17.5 kU/L; specific IgE class 4–6) experienced treatment-related AEs compared to subjects with low specific IgE levels (≤17.5 kU/L; specific IgE class 0–3). Specifically, for subjects on active treatment, 56% of subjects with high IgE levels experienced treatment-related AEs compared to 34% of subjects with low IgE levels. This trend was also reflected in the subgroup analyses presented in Figures 1 and 2. While the observed differences did not reach statistical significance, a trend toward a higher risk of experiencing moderate or severe treatment-related AEs with increasing IgE level was observed (p = 0.05).

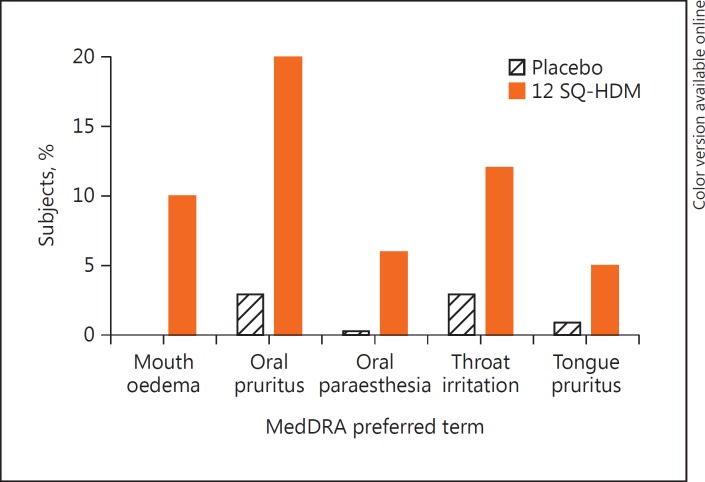

Most Common Treatment-Related AEs

Figure 3 provides an overview of the most common treatment-related AEs in the 2 clinical trials (defined as treatment-related AEs reported by ≥5% of subjects on active treatment). All were local allergic reactions; the most common was oral pruritus, as reported by 20% of subjects on active treatment, followed by throat irritation (12%) and mouth oedema (10%).

Fig. 3.

Most frequent treatment-related adverse events (experienced by ≥5% of subjects) for all adult subjects in the 2 trials (MT-04 + MT-06). MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

The onset and duration of the most common treatment-related AEs were further investigated. In general, the most common treatment-related AEs occurred within the first few days of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet and lasted for approximately 5 min after tablet intake (data not shown).

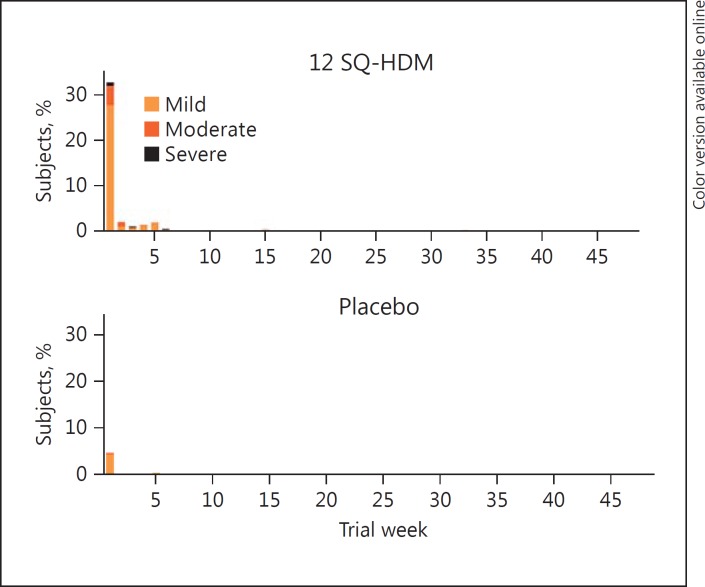

In Figure 4, the first onset of the most common (≥5%) treatment-related AEs is presented as the percentage of subjects experiencing a new AE during each week of the first year of treatment. In both treatment groups, the proportion of subjects experiencing onset of a new AE was greatest during the first week of treatment (approximately 33% of subjects on active treatment, 5% of subjects on placebo). By week 2, the proportions had dropped considerably to fewer than 3% of subjects in both groups. Thus, for most subjects experiencing the most common treatment-related AEs, these local allergic reactions occurred for the first time during the first week of treatment. In contrast, very few subjects experienced one of these reactions for the first time later than 5 weeks after treatment initiation.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of subjects with onset of a new treatment-related adverse event (AE) (the most frequent [≥5%] treatment-related AEs), during each week of the first year of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (pooled data from MT-04 and MT-06).

The median duration (defined as the time from start to stop of each individual AE in a given subject) for the most common treatment-related AEs were as follows: oral pruritus 6 days, throat irritation 9 days, and mouth oedema 21 days (all for subjects on active treatment); 19% of subjects on active treatment had at least 1 of the most common treatment-related AEs ongoing in week 4 of the trial. After 12 and 24 weeks, this proportion was reduced to 14 and 7%, respectively (online suppl. Fig. S1).

Severe Treatment-Related AEs

A summary of all severe treatment-related AEs and treatment-related SAEs experienced by subjects in the groups on 12 SQ-HDM in the 2 trials are listed in Table 3. Most of these cases were local allergic reactions.

Table 3.

Overview of all severe treatment-related AEs and treatment-related SAEs reported by subjects on 12 SQ-HDM in the 2 trials

| Trial | Dose | MedDRA preferred term | Action taken to intervention medication | Day of onset | Duration, days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe treatment-related AEs | |||||

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Submaxillary gland enlargement | Discontinued | 8 | 2 |

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Mouth oedema | Discontinued | 2 | 5 |

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Tongue oedema | Discontinued | 38 | 37 |

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Oral pruritus | Discontinued | 38 | NR |

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Dysphagia | Interrupted | 1 | 153 |

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Asthma | Discontinued | 257 | 16 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Throat irritation | Discontinued | 1 | 83 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Mouth oedema | Discontinued | 15 | 11 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Oral pain | Discontinued | 15 | 11 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Lip oedema | None | 274 | 1 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Throat irritation | None | 1 | 1 |

| MT-06 | 12 SQ-HDM | Oral pruritus | None | 1 | 1 |

| Treatment-related SAEsa | |||||

| MT-04 | 12 SQ-HDM | Asthma exacerbation (moderate) | Discontinued | 1 | 79 |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; NR, not recovered.

Assessed as serious by investigator or sponsor.

One severe treatment-related AE of asthma was reported in the MT-04 trial, 8.5 months after the initial administration of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. The subject developed a severe asthma exacerbation. Initially, the exacerbation was treated with ICS and short-acting β-agonists. Later, oral corticosteroid was added due to lack of efficacy of the initial treatment, and treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet was discontinued 7 days after the onset of the AE. On day 9, an antibiotic was added, and 2 days later the subject was additionally treated with intravenous steroid. The subject recovered on day 16 after the start of the AE.

Treatment-Related SAEs

Table 3 provides an overview of treatment-related SAEs experienced by subjects on active treatment. While no treatment-related SAEs were reported by subjects on 12 SQ-HDM in the MT-06 trial, 1 treatment-related SAE was reported as asthma exacerbation in the MT-04 trial. The subject developed worsening of respiratory symptoms over the first 6 days after the initiation of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (reported as asthma exacerbation and assessed as moderate by the investigator). The event was classified as serious due to hospitalisation of the subject (on day 8). Treatment included systemic and inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonist. The subject was discontinued from the trial on day 6 and recovered fully. The subject had a viral infection in the period prior to initiation of treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. According to the investigator, an alternative aetiology was a recent viral infection.

Adverse Reactions of Special Interest

No deaths or cases of anaphylactic shock were reported in the 2 trials and no events were reported as systemic allergic reactions. No treatment-related AEs involved local allergic swelling compromising the airways.

In the MT-06 trial, a treatment-related AE reported by the investigator as “very mild laryngeal oedema, no vital risk” was treated with adrenaline. This reaction occurred with 12 SQ-HDM upon initial administration of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, which was performed under medical supervision as required by the protocol. The second administration was also performed under medical supervision, and the subject completed the trial with mild oral pruritus as the only subsequently reported treatment-related AE [37].

Discussion

This pooled analysis of safety and tolerability of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (dose 12 SQ-HDM) confirmed that treatment is well tolerated by a broad European population of adult patients with HDM respiratory allergic disease. The safety profile was comparable for subjects with moderate-to-severe HDM allergic rhinitis and subjects with not well-controlled HDM allergic asthma. No unexpected safety concerns emerged from the clinical development programme of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, and the overall safety and tolerability profile was similar to that observed for other SLIT-tablets, including the authorised products GRAZAX/GRASTEK, RAGWITEK, ACTAIR, and ORALAIR [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23].

Since treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet involves administering to patients the allergen causing their allergy symptoms, local allergic reactions are to be expected during treatment. Accordingly, the pooled safety data showed a greater proportion of subjects on active treatment reporting treatment-related AEs compared to placebo. Most reported AEs were mild or moderate local allergic reactions occurring within the first few days of treatment initiation. For most subjects, the local treatment-related AEs were resolved within days to weeks, but a small subset appeared to have more persistent, mild local AEs occurring daily throughout the treatment period. The duration in minutes of these treatment-related AEs was not assessed in the phase III trials but is known from phase I trials to be in the range of minutes to hours [27]. In case a patient experiences significant local adverse reactions due to treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, anti-allergic medication (e.g., antihistamines) is recommended.

In the pooled dataset, approximately one-third of subjects were only sensitised to HDM, whereas most were sensitised to additional allergens. The safety analysis revealed no differences in safety and tolerability of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet based on subjects' sensitisation status.

In the investigated populations, a dose of 12 SQ-HDM had a safety and tolerability profile that supports at-home sublingual administration once the first tablet is tolerated when administered under physician supervision. In addition, the requirement for at least 30 min of monitoring after the initial administration of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet provides an opportunity for discussion and possible treatment of any immediate AEs.

A potential concern with SLIT is the risk of severe local allergic reactions leading to swelling which may compromise the airways. Across the trials included in the present safety analysis, 10% of subjects on active treatment reported the local treatment-related AE mouth oedema, and a small number of severe local treatment-related AEs were reported. No events involving compromised airways were reported and the treatment-related AEs were all manageable. In addition, no AEs were reported as systemic allergic reactions. As such, nothing in the pooled safety data suggests a need for co-prescription of adrenaline auto-injectors during treatment with the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet, as is currently a requirement for initiating SLIT-tablet treatment in the US (but not in Europe or elsewhere).

An important aspect of this safety investigation is the assessment of patients with HDM allergic asthma. Severe uncontrolled asthma is a known risk factor for anaphylaxis [38, 39, 40] and is believed to constitute a risk during AIT, even if AIT is also used to treat allergic asthma [11]. Thus, AIT is often contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled or severe asthma [41]. In this paper, safety data from 2 large trials were analysed to reveal differences in safety and tolerability that might arise from differences in the manifestation and severity of HDM respiratory allergic disease. With regard to treatment-related AEs, no significant differences based on asthma, asthma medication level, or asthma control were observed. The overall comparison (of all AEs, not only those related to the treatment) indicated that subjects with not well-controlled asthma (in both placebo and active groups) experienced more AEs of a higher severity and had more discontinuations due to AEs compared with the population with controlled asthma in general.

Because of the known risk in asthma, patients with FEV1 <70% of the predicted value after adequate pharmacological treatment at randomisation and patients who had experienced a severe asthma exacerbation within the last 3 months prior to randomisation were not investigated in the clinical development programme. Within these safety precautions, the MT-04 trial included a subgroup of subjects with HDM allergic asthma that was uncontrolled at randomisation according to the GINA 2010 definition of uncontrolled asthma [42]. There was no evidence of active treatment affecting this subgroup any differently with respect to treatment-related AEs compared to subjects with controlled asthma.

Although the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet has been shown to improve HDM allergic asthma symptoms, the risk of acute asthma exacerbation remains for patients with risk factors, as observed by the reported treatment-related SAE in the MT-04 trial where a patient with recent viral infection developed a moderate asthma exacerbation within the first week of the trial. Thus, great care should be exercised in assessing patients' asthma status and risk factors (such as ongoing viral infection, recent severe exacerbation, and FEV1 <70%), even though the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet has been shown to be well tolerated in subjects with HDM allergic asthma not well controlled by ICS, regardless of asthma control level according to the GINA 2010 criteria [42].

In conclusion, the presented results from 2 large randomised placebo-controlled trials including 1,215 subjects show that the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (dose 12 SQ-HDM) is well tolerated and suitable for at-home administration in patients with HDM respiratory allergic disease. This includes patients with asthma symptoms not well controlled by allergy pharmacotherapy provided that their lung function allows (FEV1 >70%) and that their asthma status, including risk factors such as recent viral infection, is carefully assessed. Mild-to-moderate local allergic reactions are common and usually occur at treatment initiation and subside with continued treatment.

Disclosure Statement

W. Emminger has been involved in several clinical studies for ALK. M.D. Hernández was a primary investigator in the MT-04 trial and has served on advisory boards for ALK. V. Cardona has received fees as advisor, speaker, or researcher for ALK, Allergopharma, Allergy Therapeutics, Astra, Circassia, HAL, FAES, GSK, LETI, Novartis, Shire, Stallergenes, and Uriach. F. Smeenk was a scientific advisory board member for ALK regarding the MT-04 trial and has received speaking fees from ALK. B.S. Fogh is employed by ALK, the manufacturer of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet. M.A. Calderon has received advisory fees from ALK and Hal Allergy and has received lecture fees from ALK, Allergopharma, Hal Allergy, Merck, and Stallergenes-Greer. F. de Blay has received research support from Chiesi and Stallergenes and consultancy fees from ALK, Mundipharma, and Novartis, and has served as a board member for ALK, Boehringer, Medapharma, Mundipharma, Novartis, and Stallergenes. V. Backer has been involved in several clinical studies for ALK and has received investigator fees and patient fees.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

The authors present this publication on behalf of all the involved investigators from the 2 trials. The authors would like to thank all investigators and especially the principal investigators of the 2 trials, Dr. Johann Christian Virchow (MT-04) and Dr. Pascal Demoly (MT-06). The trials were funded by ALK. In this context, the authors would like to thank the clinical trial teams at ALK for clinical project management, operational oversight, safety monitoring, data management, and statistical analyses. Medical writers Brian Sonne Stage and Ida Mosbech Smith, ALK, were responsible for medical writing, editorial, and journal submission assistance for this manuscript.

References

- 1.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, Aria Workshop Group; World Health Organization Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S147–S334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linneberg A, Henrik Nielsen N, Frolund L, Madsen F, Dirksen A, Jorgensen T. The link between allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma: a prospective population-based study. The Copenhagen Allergy Study. Allergy. 2002;57:1048–1052. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.23664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA2LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008;63((suppl 86)):8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauchau V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:758–764. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00013904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. House dust mite control measures for asthma: systematic review. Allergy. 2008;63:646–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valovirta E, Myrseth SE, Palkonen S. The voice of the patients: allergic rhinitis is not a trivial disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:1–9. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282f3f42f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canonica GW, Tarantini F, Complati E, Penagos M. Efficacy of desloratadine in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. Allergy. 2007;62:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radulovic S, Calderon MA, Wilson D, Durham S. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12:CD002893. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002893.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creticos PS, Reed CE, Norman PS, et al. Ragweed immunotherapy in adult asthma. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:501–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602223340804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compalati E, Passalacqua G, Bonini M, Canonica GW. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy for house dust mites respiratory allergy: results of a GA2LEN meta-analysis. Allergy. 2009;64:1570–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GINA Executive Committee, Global Initiative for Asthma . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin HS, Liss GM, Bernstein DI. Evaluation of near-fatal reactions to allergen immunotherapy injections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein DI, Wanner M, Borish L, Liss GM, Immunotherapy Committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and skin testing: 1990–2001. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:S1–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfaar O, Bachert C, Bufe A, et al. Guideline on allergen-specific immunotherapy in IgE-mediated allergic diseases. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:282–319. doi: 10.1007/s40629-014-0032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmann K, Worm M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual tablets of house dust mites allergen extracts in adults with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1608–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaiss M, Maloney J, Nolte H, Gawchik S, Yao R, Skoner DP. Efficacy and safety of timothy grass allergy immunotherapy tablets in North American children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox LS, Casale TB, Nayak AS, et al. Clinical efficacy of 300IR 5-grass pollen sublingual tablet in a US study: the importance of allergen-specific serum IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1327–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creticos PS, Maloney J, Bernstein DI, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a ragweed allergy immunotherapy tablet in North American and European adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1342–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durham SR, Yang WH, Pedersen MR, Johansen N, Rak S. Sublingual immunotherapy with once-daily grass allergen tablets: a randomized controlled trial in seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maloney J, Bernstein DI, Nelson H, et al. Efficacy and safety of grass sublingual immunotherapy tablet, MK-7243: a large randomized controlled trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosbech H, Canonica GW, Backer V, et al. SQ house dust mite sublingually administered immunotherapy tablet (ALK) improves allergic rhinitis in patients with house dust mite allergic asthma and rhinitis symptoms. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson HS, Nolte H, Creticos P, Maloney J, Wu J, Bernstein DI. Efficacy and safety of timothy grass allergy immunotherapy tablet treatment in North American adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virchow JC, Backer V, Kuna P, et al. Efficacy of a house dust mite sublingual allergen immunotherapy tablet in adults with allergic asthma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1715–1725. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demoly P, Emminger W, Rehm D, Backer V, Tommerup L, Kleine-Tebbe J. Effective treatment of house dust mite-induced allergic rhinitis with 2 doses of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet: results from a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Incorvaia C, Masieri S, Berto P, Scurati S, Frati F. Specific immunotherapy by the sublingual route for respiratory allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corzo JL, Carrillo T, Pedemonte C, et al. Tolerability during double-blinded randomised phase I trials with the house dust mite allergy immunotherapy tablet in adults and children. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okubo K, Masuyama K, Imai T, et al. Efficacy and safety of the SQ house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet in Japanese adults and adolescents with house dust mite-induced allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1840–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Blay F, Kuna P, Prieto L, et al. SQ HDM SLIT-tablet (ALK) in treatment of asthma - post hoc results from a randomised trial. Respir Med. 2014;108:1430–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolte H, Bernstein DI, Nelson HS, et al. Efficacy of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet in North American adolescents and adults in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1631–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosbech H, Deckelmann R, de BF, et al. Standardized quality (SQ) house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablet (ALK) reduces inhaled corticosteroid use while maintaining asthma control: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolte H, Maloney J, Nelson HS, et al. Onset and dose-related efficacy of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy tablets in an environmental exposure chamber. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1494–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Adopted by the WMA General Assembly in Helsinki (1964) and as amended by the WMA General Assembly, 2008.

- 34.International Conference on Harmonization ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Topic E6(R1): Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. 1996.

- 35.Henmar H, Frisenette SM, Grosch K, et al. Fractionation of source materials leads to a high reproducibility of the SQ house dust mite SLIT-tablets. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;169:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000444016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.International Conference on Harmonization ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline Topic E2A. Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demoly P, Emminger W, Rehm D, Backer V, Tommerup L, Kleine-Tebbe J. Effective treatment of house dust mite-induced allergic rhinitis with 2 doses of the SQ HDM SLIT-tablet: results from a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, et al. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:477–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, et al. Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2014;69:1026–1045. doi: 10.1111/all.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Bilo MB, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines: summary. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ALK-Abelló A/S GRAZAX Summary of Product Characteristics. 2015.

- 42.GINA Executive Committee, Global Initiative for Asthma . Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Bethesda: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data