Abstract.

The function of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in liver injury resulted by dengue virus (DENV) infection have not yet been explored. The differential expression profiles of lncRNAs (as well as mRNAs) in the L-02 liver cells infected by DENV1, DENV2, or uninfected were compared and analyzed after a high throughput RNA seq. The significantly up-regulated and down-regulated lncRNAs (or mRNAs) resulted by DENV infection were identified with a cutoff value at log2 (ratio) ≥ 1.5 and log2 (ratio) ≤ −1.5 (ratio = the reads of the lncRNAs or mRNAs from the infection groups divided by the reads from the control group). Several differentially expressed lncRNAs were verified with reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Target gene analysis, pre-miRNA prediction, and the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network construction were performed to predict the function of the differentially expressed lncRNAs. The differentially expressed lncRNAs were associated with biosynthesis, DNA/RNA related processes, inhibition of estrogen signaling pathway, sterol biosynthetic process, protein dimerization activity, vesicular fraction in DENV1 infection group; and with protein secretion, methyltransferase process, host cell cytoskeleton reorganization and the small GTPase Ras superfamily, inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis in DENV2 infection. LncRNAs might be novel diagnostic markers and targets for further researches on dengue infection and liver injury resulted by dengue virus.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue is one of the most infectious human viral diseases transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. It is caused by dengue virus (DENV), a single stranded RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, which has four antigenically distinct serotypes (DENV1–4).1 DENV infection in humans causes a broad spectrum of illnesses including asymptomatic infection, undifferentiated fever (dengue fever [DF]), and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome.2 It is estimated that 390 million dengue infections occur annually, among which nearly 100 million show manifestations at various severity. Whereas the actual number of infection is three times more than the dengue burden estimated by the World Health Organization.3

Liver cells are a prime target for DENV infection, which has been confirmed in the biopsies or autopsies of some cases.4–6 DENV infection causes an intense immune activation, leading to direct or indirect liver damage or hepatitis. Elevated levels of serum transaminases were found in dengue patients and being correlated with hemorrhagic symptoms.7–9 The proportion of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevation was approximately 80% in DHF patients and 75% in DF patients, whereas the proportion of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation was approximately 54% in DHF patients and 52% in DF patients.10 The pathogenesis of liver injury in dengue patients is believed to be direct pathological damage caused by virus infection or an indirect immune pathological injury resulting from immune responses.7 An eventual outcome of hepatocyte infection by DENV is cellular apoptosis.11 However, the exact mechanism through which the host immunity damages the liver is still unknown.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts longer than 200 nt, which have been gradually recognized to exert a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression. Recently, researchers have started to explore the implications of lncRNAs alteration in hepatic pathophysiology.12,13 Several studies have reported that lncRNAs expression in the liver may contribute to liver pathology or is associated with specific liver diseases.14–16 The lncRNAs have been increasingly recognized to function in many biological processes or the pathogenesis through diverse mechanisms. LncRNA provides us a new resource to identify disease-associated biomarkers or molecular targets for therapy, as well as for DENV infection.

In this research, we aimed to identify the expression profiles of lncRNAs for L-02 cells infected with DENV1 and DENV2, which were the predominant serotypes in local populations in mainland China, and to explore their potential functions on gene transcription regulation and signaling transduction relevant to liver damage.17,18

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, virus harvesting, and titer detection.

C6/36 insect cells (bought from ATCC) were grown in RPMI medium 1640 (RPMI-1640) (Life Technologies, Camarillo, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Penicillin (200 U/mL), and Streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 28°C. L-02 cells (bought from ATCC, a normal liver cell line keeping the morphological and genetic characteristics of normal liver cells) were cultured with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin (200 U/mL), and Streptomycin (100 μg/mL) in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

The viruses used in this study, DENV1 (strain Hawaii) and DENV2 (strain New Guinea C) were sustained with C6/36 cells in RPMI-1640 medium containing 2% FBS; the medium containing the virus particles was harvested 5 days after infection, cell debris was precipitated by 800 rpm centrifugation, and aliquots of the supernatant were stored at −80°C.

The titers of the harvested dengue virus particles were determined with the method reported by Ramakrishnan.19 The viral titer was evaluated as the tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) per milliliter, and then, the TCID50 was converted to plaque forming units by multiplying by 0.7.20

The confirmation of DENV infection.

L-02 cells were seeded into the wells containing coverslips in a 12-well plate and cultured for 24 hours. The cells in each well were infected with DENV1 or DENV2 stock at a mulplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0, respectively. At the time of 24, 48, and 72 hours after infection, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, then permeablized with 0.5% TritonX-100/PBS for 20 minutes and blocked with 10% FBS/PBS for 1 hour. The cells were then incubated for 2 hours with the primary rat monoclonal antibody specific to the nonstructural glycoprotein-1 (NS1) of DENV1 or DENV2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX) in 1:200 dilution. After washed with PBS for three times and 5 minutes for each with gentle shaking, the cells were incubated for 1 hour with a red fluorescence–labeled secondary goat anti-rat antibody (Santa) in 1:500 dilution. The cells were then washed with PBS as mentioned previously. The coverslips were taken out of the wells and rinsed with ddH2O, air-dried, and mounted with the mounting oil containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to stain the nuclei. The virus particles stained with red fluorescence in the cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

The optimization of infection condition.

The method reported by Pattanakitsakul et al.21 was followed for investigation of the optimal infection condition which resulted in the most significant pathogenesis, including MOI, infection time, and postinfection duration. In DENV1 or DENV2 infection simulation in vitro, the 100% confluent monolayer of L-02 cells in each well of the 6-well plate, containing approximately 1 × 106 cells, was infected with DENV1 or DENV2 for 2 hours at 37°C at an MOI of 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0, respectively. The viruses for infection at various MOI were diluted to a final volume of 1 mL with complete RPMI medium. When the infection finished, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any unbounded virus particles; then, 2 mL maintenance medium was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 24, 48, and 72 hours. The supernatant was collected at each time point and kept for AST and ALT detection. The AST and ALT levels of the cell culture medium from each well with different infection conditions were detected using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (MLBIO, Shanghai, China, ml027133). The infection condition with the highest AST and ALT titer was selected as the optimized condition.

RNA sequencing and differential expression identification.

In accordance with the optimized infection condition, the L-02 cells of the control, DENV1 infection, and DENV2 infection were prepared in triplicate and harvested separately. The samples were delivered to the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) for RNA sequencing. The three replicates of each group were sequenced separately and the mean reads of lncRNA and mRNA were used as the final reads. RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent (15596-026; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) from each sample. A RNA-sequencing quantification library was constructed by the BGI. Paired-end sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

The alignment of the sequences was performed on the human genome version UCSC hg19 and lncRNAs version NONCODE V3.0, and the calculation was performed based on FPKM (Fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments). Bioinformatics processing of raw data was performed by the BGI. The differential expression level of the specific lncRNAs or mRNAs were analyzed with Cuffdiff software, using the reads of DENV1 infection, and DENV2 infection divided by the reads of the control group, with a cutoff value of log2 (ratio) (ratio = DENV1/control, DENV2/control). If the log2 (ratio) ≥ 1.5, the expression was defined as upregulation; otherwise, if the log2 (ratio) ≤ −1.5, the expression was defined as downregulation.22,23

Annotation and prediction for the potential target genes of the lncRNAs.

The transcripts alignment software TopHat2 was used to map the differentially expressed lncRNAs to the reference genome.24 Then, Bowtie software was used to break the reads of those not mapped and mapping was repeated.25 By doing this, the mapped location of the lncRNA in the upstream (promoter region) or downstream (3′ untranscribed region) of a gene, which was defined as a potential target gene, could be inferred. If the lncRNA was mapped in the upstream or downstream of a gene, it may have a chance to overlap with a cis-regulation element probably involved in transcriptional regulation. The function information of the target genes was searched in PubMed database.

Pre-miRNA prediction for the differentially expressed lncRNAs in the different treatment groups.

Mature miRNAs recognize the target mRNA through imperfect base pairing and most commonly result in translational inhibition or destabilization of the target mRNA.26,27 A lncRNA may be the precursor of a miRNA and have a unique function.28,29 Therefore, the lncRNAs were aligned with the miRNAs in the miRBase to identify the potential pre-miRNA. The function of pre-miRNA was searched in HMDD v2.0: the Human microRNA Disease Database version 2.0 (http://www.cuilab.cn/hmdd).

Verification of the differential expression of the lncRNAs with RT-qPCR.

The total RNAs were extracted with a Trizol reagent (15596-026; Invitrogen) from the L-02 cells of the DENV1 infection, DENV2 infection, and control. Transcription in each sample was conducted using the GoscriptTM Reverse Transcription System (A5000; Promega, Beijing, China). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers of the differentially expressed lncRNAs were designed with DNAstar. A total of 1 μg of cDNA in a final volume of 50 μL was used for amplification with SYBR Green RT-qPCR Master Mix-SYBR Advantage (639676; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) on the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The lncRNAs expression levels were evaluated by ΔCt (threshold cycle difference, ΔCt = mean Ct value of lncRNA−mean Ct value of reference β-actin mRNA). The relative expression of the lncRNAs was evaluated by the value of 2−ΔCt.30 The detection of the lncRNAs’ expression was repeated for three times, and the relative expression difference between the treatment group and the control group was analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) method by using SPSS19.0. A statistically significant difference was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Analysis of the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network.

The differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in the comparative groups were extracted to form a union dataset. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated using R software (Wolfgang Viechtbauer, 2015), and the threshold value of the correlation coefficient was set at “≥ 0.80”; the positive correlation coefficient represented a positive correlation, and the negative correlation coefficient represented a negative correlation. Then, the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network was built and exported based on the correlation between the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs using Cytoscape software (the Cytoscape Consortium, San Diego, CA). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and gene ontology (GO) enrichment for the differentially expressed mRNAs, which interacting with lncRNAs, in co-expression networks were performed using DAVID database (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).31

RESULTS

The optimization of infection condition by detecting AST and ALT levels with ELISA.

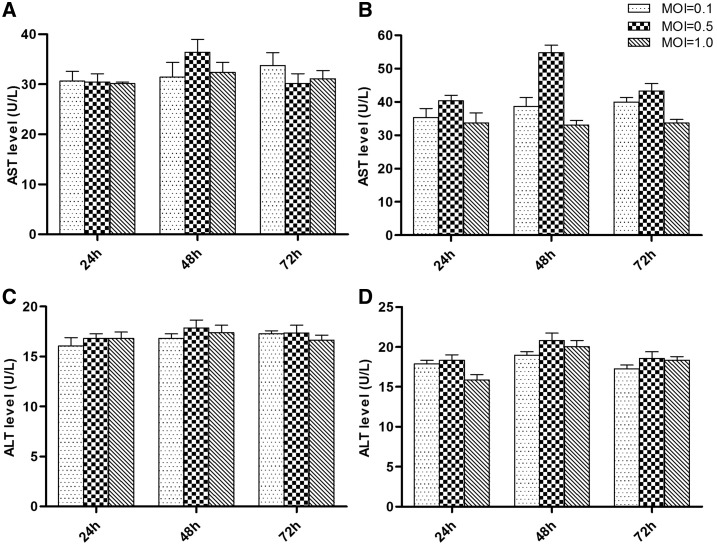

DENV1 and DENV2 infection was confirmed by using immunofluorescence microscopy, which was shown in Supplemental File 1. The highest titer of AST or ALT was both detected in the cell culture medium of L-02 infected with DENV1 or DENV2 for 2 hours at an MOI of 0.5 and with 48 hours postinfection duration. The results were shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Detection of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level in L-02 cells infected by DENV1 and DENV2. The y axis represented the level (U/L) of AST or ALT. Each bar showed the value of the mean ± SD of different mulplicity of infections (MOIs) and different times after infection. The level of AST was higher than that of ALT at all infection condition, and the highest level of AST and ALT was found at the MOI of 0.5 with 48 hours infection by DENV1 or DENV2. (A) The level of AST in L-02 cells infected by DENV1; (B) The level of AST in L-02 cells infected by DENV2; (C) The level of ALT in L-02 cells infected by DENV1; (D) The level of ALT in L-02 cells infected by DENV2. DENV = dengue virus.

The profiles of differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs.

In this research, the differentially expressed lncRNAs were selected using Cuffdiff software. Compared with the control group, 107 differentially expressed lncRNAs, including 74 upregulated and 33 downregulated, were found in the DENV1 infection group; 36 differentially expressed lncRNAs, including 15 upregulated and 21 downregulated, were found in the DENV2 infection group. As for mRNAs, compared with the control, 79 differentially expressed mRNAs, including 39 upregulated and 40 downregulated, were found in the DENV1 infection group; and 31 differentially expressed mRNAs, including 15 upregulated and 16 downregulated, were found in the DENV2 infection group.

The target genes of differentially expressed lncRNAs.

In annotation for the differentially expressed lncRNAs, its complementary sequence on a gene was analyzed. If the complementary sequence was in the upstream or downstream of a gene, it may have a chance to overlap with cis-regulation elements and probably involves in transcriptional regulation. The complementary position of the known differentially expressed lncRNAs in the up or down stream of a potential target gene was shown in Table 1, and the related information of the novel lncRNAs was shown in Table 2. The function information of the target genes was searched in PubMed database, and the results were summarized in Table 3. In DENV1 infection, compared with the control, functions of the predicted target genes were characterized by biosynthesis, such as Gene 7167 (Gene ID) involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, Gene 2222 involved in mevalonate pathway; and DNA/RNA related enzymes such as Gene 11044 encoding a DNA polymerase, Gene 246243 encoding an endonuclease, and Gene 5488 encoding a methyltransferase. In DENV2 infection, compared with the control group, the target gene prediction found Gene 8492 involved in structural reorganizations associated with learning and memory, and Gene 6371 involved in targeting of secretory protein to the endoplasmic reticulum.

Table 1.

The differentially expressed known long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the up or down stream of a target gene

| lncRNA id | Gene id | Up or down stream | Group | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n372943 | 7167 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| n338527 | 115708 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| n372894 | 7167 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| n370000 | 55904 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| n385519 | 253650 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| n379481 | 8492 | downstream_2k | DENV2 | Down |

| n370000 | 55904 | upstream_2k | DENV2 | Up |

DENV = dengue virus.

Table 2.

The differentially expressed novel long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the up or down stream of a target gene

| lncRNA id | Gene id | Up or down stream | Group | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XLOC038199 | 100316904 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC032293 | 11044 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC037587 | 728194 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC008742 | 2900 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC023418 | 246243 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC033626 | 54888 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC019652 | 2015 | downstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC043236 | 25920 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC023862 | 112942 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC034320 | 3308 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC035124 | 10473 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Up |

| XLOC039796 | 2222 | upstream_2k | DENV1 | Down |

| XLOC031703 | 6731 | upstream_2k | DENV2 | Up |

| XLOC041701 | 10927 | upstream_2k | DENV2 | Down |

DENV = dengue virus.

Table 3.

Annotation for target genes of differentially expressed long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) from each infection group compared with the control

| Gene id | Annotation | Group |

|---|---|---|

| 2222 | Encodes a membrane-associated enzyme located at a branch point in the mevalonate pathway | DENV1 |

| 7167 | Impacts on glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | DENV1 |

| 11044 | Encodes a DNA polymerase that is likely involved in DNA repair | DENV1 |

| 2900 | Encodes a protein that belongs to the glutamate-gated ionic channel family | DENV1 |

| 246243 | Encodes an endonuclease that specifically degrades the RNA of RNA-DNA hybrids | DENV1 |

| 54888 | Encodes a methyltransferase that catalyzes the methylation of cytosine to 5-methylcytosine | DENV1 |

| 2015 | Encodes a protein that has a domain resembling seven transmembrane G protein-coupled hormone receptors | DENV1 |

| 10473 | Encodes a member of the HMGN protein family to reduce the compactness of the chromatin fiber | DENV1 |

| 55904 | Inhibits cell cycle progression | DENV2 |

| 8492 | May be involved in structural reorganizations associated with learning and memory | DENV2 |

| 6731 | Encodes a ribonucleoprotein complex that mediates the target of secretory protein to the endoplasmic reticulum | DENV2 |

DENV = dengue virus.

Pre-miRNA prediction for the differentially expressed lncRNAs.

Based on the complementarity between lncRNAs and pre-miRNA, the known lncRNAs predicted to be a potential miRNA precursor were shown in Table 4. The function of predicted pre-miRNAs in different infection group was shown as follows: Hsa-mir-22 (miRNA ID) found in DENV1 infection group could inhibit estrogen signaling by directly targeting at the estrogen receptor alpha mRNA; Hsa-mir-29b-2 found in DENV2 infection was a potential noninvasive biomarker in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Alzheimer’s disease; downregulation of hsa-mir-29c, which was found in DENV2 infection, would lead to derepression of its target DNA (methyltransferase 3a) transcription, promote ischemic brain damage, inhibit cell proliferation, and induce apoptosis in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 4.

The pre-miRNA prediction for differentially expressed long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) from each infection group compared with the control

| lncRNA id | miRNA id | Length | Q value | Regulation | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n345423 | hsa-mir-29b-2 | 81 | 2.0E-41 | Down | DENV2 |

| n345423 | hsa-mir-29c | 88 | 1.0E-45 | Down | DENV2 |

| n408292 | hsa-mir-22 | 85 | 8.0E-44 | Down | DENV1 |

| XLOC011870 | hsa-mir-1268a | 52 | 8.0E-15 | Down | DENV1 |

| XLOC026695 | hsa-mir-3648 | 180 | 1.0E-100 | Down | DENV2 |

DENV = dengue virus.

Verification of the differential expression of the lncRNAs with RT-qPCR.

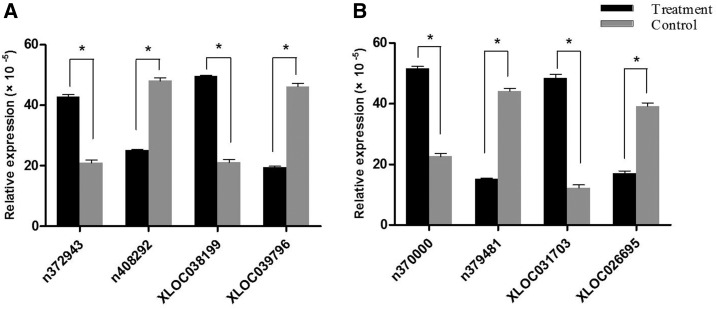

To validate our results independently and determine the role of lncRNAs in DENV infection, several differentially expressed lncRNAs were selected for expression detection with RT-qPCR. The PCR primers of β-actin (internal control) and the lncRNAs were listed in Table 5. The relative expression level (2−ΔCt) of each lncRNAs displayed in Supplemental File 2 was shown in the histograms in Figure 2. The differential expression of the lncRNAs in comparative groups evaluated by the 2−ΔCt values in quantitative real-time PCR was consistent with the RNA-seq relative expression level evaluated by log2 (ratio). The expression of n372943 and XLOC038199 in DENV1 infection group compared with the control, n370000 and XLOC031703 in DENV2 infection group compared with the control were upregulated; the expression of n408292 and XLOC039796 in DENV1 infection group compared with the control, n379481 and XLOC026695 in DENV2 infection group compared with the control were downregulated.

Table 5.

The primers sequences of differentially expressed long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs)

| lncRNA id | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TTCACCACCACAGCCGAAAG | AACGCTCATTGCCGATGGTG- 3 |

| n372943 | GCGGAATGGCAAGGAATCAG | CACCACCCAGCAAGTTTCCAAG |

| n408292 | AGGTTGACGTGGCAGAGAAG | TCGCTTTGGCTTCGGCTTTAG |

| n370000 | GTGCAGCTGTTGGAGTCTGG | CCTTCACGGAGTCTGCGTAG |

| n379481 | TTTGGTTTCCTGCTCTCCTGTC | GTCTCACCAGGGTACCTACAAAG |

| XLOC038199 | TGGCTGAGCCATCCTGAAAG | GACCACTCTTCCCTCCTCTC |

| XLOC039796 | ATGCTTTCTGCCAGCCAGAG | AGTTGGACACTGGGTACTGTAG |

| XLOC031703 | AGTGCGGGAAGACATTCTGG | TCCAGCTTATTGCCGACTGC |

| XLOC026695 | ACAATGATTTACTTCATTTGCTCAATC | AAACTGCCCTCATGCACACC |

Figure 2.

Verification of the differential expression of the long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) with reverse transcription quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The y axis represented the relative expression level (2−ΔCt) of each lncRNAs. The dark bar showed the value of the infection group and the gray bar showed the value of the control group. The relative expression level (2−ΔCt) of each lncRNAs displayed in histograms was expressed as the mean ± SD *statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05). (A) DENV1 infection group compared with the control group, the relative expression of n372943 and XLOC038199 was significantly upregulated, and which of n408292 and XLOC039796 was significantly down-regulated. (B) DENV2 group compared with the control group, the relative expression of n370000 and XLOC031703 was significantly upregulated, and which of n379481 and XLOC026695 was significantly downregulated. DENV = dengue virus.

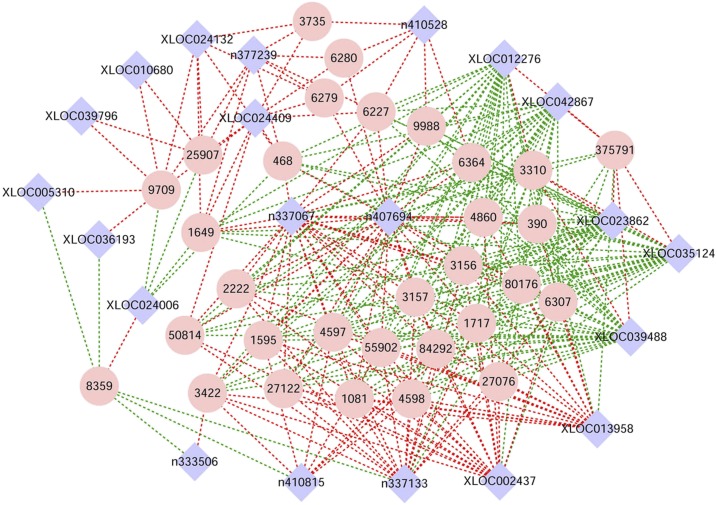

The co-expression network of lncRNA-mRNA.

The co-expression networks cited here were constructed based on the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in the groups of DENV1, DENV2 infection compared with the control group. A total of 68 interacting nodes (shown with red or green lines) were identified in the DENV1 group compared with the control group; two significant nodes were found in n337067 interacting with 25 mRNAs, and n407694 interacting with 25 mRNAs (Figure 3, Supplemental File 3). Furthermore, two same KEGG pathways were identified from the mRNAs within the two interacting nodes, respectively, including the pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (KEGG term: hsa00900) and steroid biosynthesis (hsa00100). The GO enrichment on the mRNAs within these two nodes showed the sterol biosynthetic process (GO term: 0016126) in biological process, protein dimerization activity (GO term: 0046983) in molecular function, and vesicular fraction (GO term: 0042598) in cellular component.

Figure 3.

The long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)-mRNA co-expression network in DENV1 infection group compared with the control. A pink circle represented an mRNA, and a blue diamond represented an lncRNA; a red dashed line indicated a positive correlation, and a green dashed line indicated a negative correlation. The lncRNA shown in the blue diamond potentially interacted with the mRNA in the pink circle connected by a dashed line. A total of 68 interacting nodes (shown with red or green lines) were identified in the DENV1 group compared with the control group. Two significant nodes were found in n337067 interacting with 25 mRNAs, and n407694 interacting with 25 mRNAs (Supplemental File 3). Two same kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathways were identified from the mRNAs within the two interacting nodes, respectively, including the pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (KEGG term: hsa00900) and steroid biosynthesis (hsa00100). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment on the mRNAs within these two nodes showed the sterol biosynthetic process (GO term: 0016126) in biological process, protein dimerization activity (GO term: 0046983) in molecular function, and vesicular fraction (GO term: 0042598) in cellular component. DENV = dengue virus. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Fifty interacting nodes were found in the DENV2 group compared with the control, in which two significant nodes were found in the positive correlations of 25 lncRNAs (two known lncRNAs and 23 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 51655) of small GTPase Ras superfamily, and 25 lncRNAs (five known lncRNAs and 20 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 90120) of chromosome 9 open reading frame 69. A significant node was found in the negative correlations of 22 lncRNAs (three known lncRNAs and 19 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 8359) of the nucleosome structure of the chromosomal fiber in eukaryotes (Figure 4, Supplemental File 4).

Figure 4.

The long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)-mRNA co-expression network in DENV2 infection group compared with the control. The information about the pink circles, blue diamonds, red dashed lines, and green dashed lines was the same as that in Figure 2 legend. Fifty interacting nodes were found in the DENV2 group compared with the control, in which two significant nodes were found in the positive correlations of 25 lncRNAs (two known lncRNAs and 23 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 51655) of small GTPase Ras superfamily, and 25 lncRNAs (five known lncRNAs and 20 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 90120) of chromosome 9 open reading frame 69. A significant node was found in the negative correlations of 22 lncRNAs (three known lncRNAs and 19 novel lncRNAs) interacting with one mRNA (Gene ID: 8359) of the nucleosome structure of the chromosomal fiber in eukaryotes (Supplemental File 4). DENV = dengue virus. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

DISCUSSION

Recently, lncRNAs have been identified to be specifically expressed or function in the infection of HBV, influenza virus, HIV, and enterovirus 71.32–35 There is evidence to show that dynamic changes in chromatin, chromosomes, and nuclear architecture are regulated by lncRNAs.36 Recent studies have shown that the expression levels of host lncRNAs are changed in response to virus infection.37,38

Clinical features have suggested that the liver is the most common organ to be involved in DENV infection.39 Hepatic injury results from either direct viral damage or a dysregulated immune-pathological reaction in response to DENV infection.40 The level of transaminases released from the liver cells may represent the extent of liver injury.

The differential expression of lncRNAs was observed in rhabdomyosarcoma cells in response to enterovirus 71 infection.35 LncRNAs function as a key regulator of negative regulation in the antiviral response and inflammatory response.41,42 Host lncRNAs are involved in the replication of HIV-1,38 regulating host innate immune response.34 In turn, viral source antisense lncRNAs are involved in modulating virus gene expression and lead to an alteration in the epigenetic landscape at the viral promoter or can promote viral replication and suppress antiviral immunity to allow its escape from cytosolic surveillance.43,44 This study showed that some lncRNAs expression was specifically upregulated or downregulated in L-02 cells infected by dengue virus.

Based on their distribution and sequence similarity, the lncRNAs may serve as precursors of the miRNAs and function to regulate endogenous expression of the miRNAs.28 Because mature miRNA is related to the RNA-induced translation repression or gene silencing, the finding of these lncRNAs potentially to be precursors of the miRNAs and the identification of their targets may help to understand the lncRNA’s function in transcription regulation. The interaction between lncRNAs and miRNAs will provide new insight and perspectives in this research field.12 The functions of the predicted pre-miRNAs found in different treatment groups were distinguished for inhibiting estrogen signaling in DENV1 infection, and methyltransferase process, inhibition of cell proliferation, and induce of apoptosis in DENV2 infection.

Four significantly regulated known lncRNAs found in the DENV1 infection, and DENV2 infection groups compared with the control group were verified with RT-qPCR and showed the same trend of regulation as the sequencing result: n372943 and n370000 were significantly upregulated; n408292 and n379481 were significantly downregulated. Four significantly regulated novel lncRNAs found in the DENV1 infection, and DENV2 infection groups compared with the control group were also verified with RT-qPCR and showed the same trend as the sequencing result:XLOC038199 and XLOC031703 were significantly upregulated; XLOC039796 and XLOC026695 were significantly downregulated. These findings were highly consistent with our RNA-sequencing analysis for the differentially expressed lncRNAs.

The co-expression network for the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs between the infection group (DENV1, DENV2) and the control group represented a potential interaction of the correlated lncRNAs and mRNAs. In DENV1 infection group compared with the control, two significant nodes were found and two same KEGG pathways were identified from the mRNAs within the two interacting nodes respectively, including the pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (KEGG term: hsa00900) and steroid biosynthesis (KEGG term: hsa00100). The GO enrichment on the mRNAs within these two nodes showed the sterol biosynthetic process (GO term: 0016126) in biological process, protein dimerization activity (GO term: 0046983) in molecular function, and vesicular fraction (GO term: 0042598) in cellular component. These findings implied a characteristic regulation of the lncRNA on host cell biosynthesis in DENV1 infection. In DENV2 infection group, compared with the control, two significant nodes were found in the positive correlations including 25 lncRNAs interacting with a mRNA of small GTPase Ras superfamily. One significant node was found in the negative correlations composed of 22 lncRNAs interacting with the mRNA (Gene ID: 8359) of the nucleosome structure of the chromosomal fiber in eukaryotes. These findings implied a characteristic regulation of the lncRNA on the host cell cytoskeleton reorganization in DENV2 infection.

These findings about the lncRNAs and the correlation with mRNAs expression may provide basic mechanistic information and possible biomarkers for the L-02 hepatic cells infected by dengue virus. The differentially expressed lncRNAs may be regulation products produced by virus invasion, host cell antiviral immunity, and apoptosis, and could be used as novel disease biomarkers or potential targets for therapy.

CONCLUSION

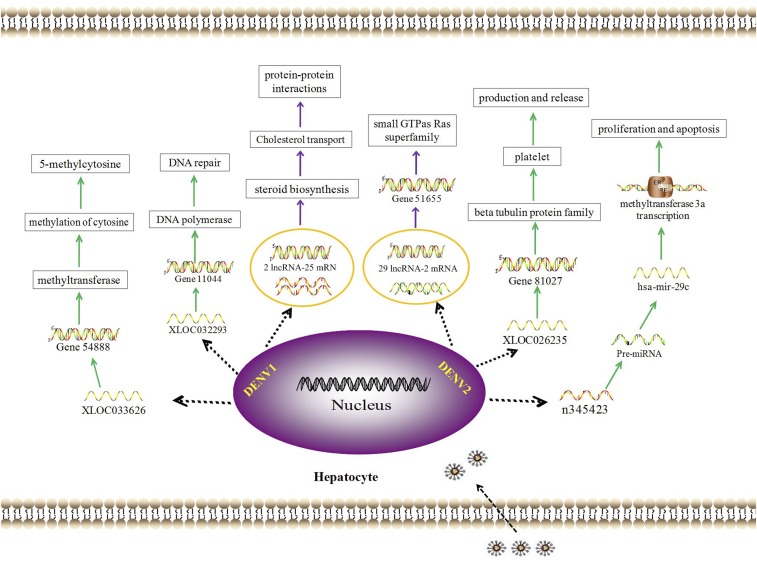

The differentially expressed lncRNAs were comprehensively analyzed by taking advantages of the L-02 cells model for DENV1 and DENV2 infection, RNA sequencing, and the integrated analyses including target gene prediction, pre-miRNA prediction, and co-expression network of lncRNA-mRNA. The predicted functions of the differentially expressed lncRNAs dominated in biosynthesis, DNA/RNA related processes, estrogen signaling, sterol biosynthetic process, protein dimerization activity, vesicular fraction in DENV1 infected L-02 cells; while in DENV2 infection group, they are dominant in protein secretion, methyltransferase process, regulation on host cell cytoskeleton reorganization, small GTPase Ras family, inhibition of cell proliferation, and induction of apoptosis (details were shown in Figure 5). LncRNAs will provide new insights and perspectives for further researches on the mechanism of dengue infection and liver injury resulted by dengue virus.

Figure 5.

Biological function of differentially expressed lncRNA in L-02 cells infected by dengue virus (DENV). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Supplementary Material

Note: Supplemental files appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guzmán MG, Kourí G, 2002. Dengue: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra G, Jain A, Prakash O, Prakash S, Kumar R, Garg RK, Pandey N, Singh M, 2015. Molecular characterization of dengue viruses circulating during 2009–2012 in Uttar Pradesh, India. J Med Virol 87: 68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt S, et al. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496: 504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thongtan T, Panyim S, Smith DR, 2004. Apoptosis in dengue virus infected liver cell lines HepG2 and Hep3B. J Med Virol 72: 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seneviratne SL, Malavige GN, de Silva HJ, 2006. Pathogenesis of liver involvement during dengue viral infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100: 608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huerre MR, et al. 2001. Liver histopathology and biological correlates in five cases of fatal dengue fever in Vietnamese children. Virchows Arch 438: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samanta J, Sharma V, 2015. Dengue and its effects on liver. World J Clin Cases 3: 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy A, Sarkar D, Chakraborty S, Chaudhuri J, Ghosh P, Chakraborty S, 2013. Profile of hepatic involvement by dengue virus in dengue infected children. N Am J Med Sci 5: 480–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan B, Patwari AK, Anand VK, 2000. Hepatic dysfunction in childhood dengue infection. J Trop Pediatr 46: 40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang XJ, Wei HX, Jiang SC, He C, Xu XJ, Peng HJ, 2016. Evaluation of aminotransferase abnormality in dengue patients: a meta analysis. Acta Trop 156: 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couvelard A, Marianneau P, Bedel C, Drouet MT, Vachon F, Hénin D, Deubel V, 1999. Report of a fatal case of dengue infection with hepatitis: demonstration of dengue antigens in hepatocytes and liver apoptosis. Hum Pathol 30: 1106–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quagliata L, Terracciano LM, 2014. Liver diseases and long non-coding RNAs: new insight and perspective. Front Med (Lausanne) 1: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerrieri F, 2015. Long non-coding RNAs era in liver cancer. World J Hepatol 7: 1971–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tripathi V, et al. 2010. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol Cell 39: 925–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan YF, Qin T, Feng L, Yu ZJ, 2013. Expression profile of altered long non-coding RNAs in patients with HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 33: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D, Yang F, Yuan JH, Zhang L, Bi HS, Zhou CC, Liu F, Wang F, Sun SH, 2013. Long noncoding RNAs associated with liver regeneration 1 accelerates hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Hepatology 58: 739–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo RN, Lin JY, Li LH, Ke CW, He JF, Zhong HJ, Zhou HQ, Peng ZQ, Yang F, Liang WJ, 2014. The prevalence and endemic nature of dengue infections in Guangdong, south China: an epidemiological, serological, and etiological study from 2005–2011. PLoS One 9: e85596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo L, Liang HY, Hu YS, Liu WJ, Wang YL, Jing QL, Zheng XL, Yang ZC, 2012. Epidemiological, virological, and entomological characteristics of dengue from 1978 to 2009 in Guangzhou, China. J Vector Ecol 37: 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramakrishnan MA, 2016. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J Virol 5: 85–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groves IJ, Reeves MB, Sinclair JH, 2009. Lytic infection of permissive cells with human cytomegalovirus is regulated by an intrinsic ‘pre-immediate-early’ repression of viral gene expression mediated by histone post-translational modification. J Gen Virol 90: 2364–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pattanakitsakul SN, Rungrojcharoenkit K, Kanlaya R, Sinchaikul S, Noisakran S, Chen ST, Malasit P, Thongboonkerd V, 2007. Proteomic analysis of host responses in HepG2 cells during dengue virus infection. J Proteome Res 6: 4592–4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung KH, Das A, Chai JC, Kim SH, Morya N, Park KS, Lee YS, Chai YG, 2015. RNA sequencing reveals distinct mechanisms underlying BET inhibitor JQ1-mediated modulation of the LPS-induced activation of BV-2 microglial cells. J Neuroinflammation 12: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Keeffe G, Hammel S, Owens RA, Keane TM, Fitzpatrick DA, Jones GW, Doyle S, 2014. RNA-seq reveals the pan-transcriptomic impact of attenuating the gliotoxin self-protection mechanism in Aspergillus fumigatus. BMC Genomics 15: 894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL, 2013. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL, 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yusuf NH, Ong WD, Redwan RM, Latip MA, Kumar SV, 2015. Discovery of precursor and mature microRNAs and their putative gene targets using high-throughput sequencing in pineapple (Ananas comosus var. comosus). Gene 571: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farazi TA, Hoell JI, Morozov P, Tuschl T, 2013. MicroRNAs in human cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 774: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai X, Cullen BR, 2007. The imprinted H19 noncoding RNA is a primary microRNA precursor. RNA 13: 313–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL, 2009. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev 23: 1494–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiong Y, Chen S, Liu L, Zhao Y, Lin W, Ni J, 2013. Increased serum microRNA-155 level associated with nonresponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20: 1089–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherman BT, Huang da W, Tan Q, Guo Y, Bour S, Liu D, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA, 2007. DAVID knowledgebase: a gene-centered database integrating heterogeneous gene annotation resources to facilitate high-throughput gene functional analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 8: 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Guo WX, Li N, Gao CF, Shi J, Tang YF, Shen F, Wu MC, Liu SR, Cheng SQ, 2015. Serum LncRNAs profiles serve as novel potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 10: e0144934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landeras-Bueno S, Ortín J, 2016. Regulation of influenza virus infection by long non-coding RNAs. Virus Res 212: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Chen CY, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT, 2013. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA and paraspeckle bodies modulate HIV-1 posttranscriptional expression. MBio 4: e00596–e00612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin Z, Guan D, Fan Q, Su J, Zheng W, Ma W, Ke C, 2013. lncRNAs expression signatures in response to enterovirus 71 infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430: 629–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mehler MF, 2009. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. BioEssays 31: 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahanda ML, Ruby T, Wittzell H, Bed’Hom B, Chaussé AM, Morin V, Oudin A, Chevalier C, Young JR, Zoorob R, 2009. Non-coding RNAs revealed during identification of genes involved in chicken immune responses. Immunogenetics 61: 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng X, et al. 2010. Unique signatures of long noncoding RNA expression in response to virus infection and altered innate immune signaling. MBio 1: e00206–e00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee LK, Gan VC, Lee VJ, Tan AS, Leo YS, Lye DC, 2012. Clinical relevance and discriminatory value of elevated liver aminotransferase levels for dengue severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martina BE, Koraka P, Osterhaus AD, 2009. Dengue virus pathogenesis: an integrated view. Clin Microbiol Rev 22: 564–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouyang J, et al. 2014. NRAV, a long noncoding RNA, modulates antiviral responses through suppression of interferon-stimulated gene transcription. Cell Host Microbe 16: 616–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter S, et al. 2013. A long noncoding RNA mediates both activation and repression of immune response genes. Science 341: 789–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saayman S, Ackley A, Turner AW, Famiglietti M, Bosque A, Clemson M, Planelles V, Morris KV, 2014. An HIV-encoded antisense long noncoding RNA epigenetically regulates viral transcription. Mol Ther 22: 1164–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding YZ, Zhang ZW, Liu YL, Shi CX, Zhang J, Zhang YG, 2016. Relationship of long noncoding RNA and viruses. Genomics 107: 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.