Abstract

5-Methylcytosine (MeC) is an endogenous modification of DNA that plays a crucial role in DNA-protein interactions, chromatin structure, epigenetic regulation, and DNA repair. MeC is produced via enzymatic methylation of C-5 position of cytosine by DNA-methyltransferases (DNMT) which use S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a cofactor. Hemimethylated CG dinucleotides generated as a result of DNA replication are specifically recognized and methylated by maintenance DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1). The accuracy of DNMT1-mediated methylation is essential for preserving tissue-specific DNA methylation and thus gene expression patterns. In the present study, we synthesized DNA duplexes containing MeC analogues with modified C-5 side chain and examined their ability to guide cytosine methylation by human DNMT1 protein. We found that the ability of 5-alkylcytosines to direct cytosine methylation decreased with increased alkyl chain length and rigidity (Methyl> Ethyl > Propyl ~ Vinyl). Molecular modeling studies indicated that this loss of activity may be caused by distorted geometry of the DNA-protein complex in the presence of unnatural alkylcytosines.

5-Methylcytosine (MeC) is the most abundant endogenous modification of DNA known to date, with approximately 5% of all cytosine bases carrying the C-5 methyl group.1 The majority of MeC residues are found within 5′-CG-3′ dinucleotides (CpG sites), where both cytidine nucleotides are methylated. Methylated CpG sites are recognized by methyl-CpG binding proteins (MBP),2 which in turn recruit histone-modifying proteins, ultimately leading to chromatin remodeling and gene silencing.3, 4

Methylation status of gene promoter regions largely determines which groups of genes are actively expressed in a given tissue.5 Cytosine methylation patterns are stable in adult cells for many generations and are transmitted to progeny cells upon cell division.6 The hemi-methylated 5′-CG-3′ sequences arising as a result of semiconservative replication are recognized by maintenance DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1), which places a methyl group on the C-5 position of cytosine of the newly synthesized strand opposite MeCG of the template strand, thereby preserving DNA methylation patterns.3 Any errors in DNMT1 action would lead to aberrant gene expression, which in turn can contribute to malignant transformation.7

It has been shown that DNMT1 fidelity can be compromised by structural modifications within 5′-CpG-3′ sites.8, 9 For example, 5-halogenated cytosines mimic 5-methylcytosine, leading to erroneous methylation of CpG sites by DNMT1.8-10 In contrast, oxidation of the C-5 methyl group of MeC to 5-hydroxymethyl-dC, 5-formyl-dC, and 5-carboxy-dC interferes with DNMT1 mediated methylation of the cytosine in the opposite strand, ultimately resulting in the removal of DNA methylation marks.11

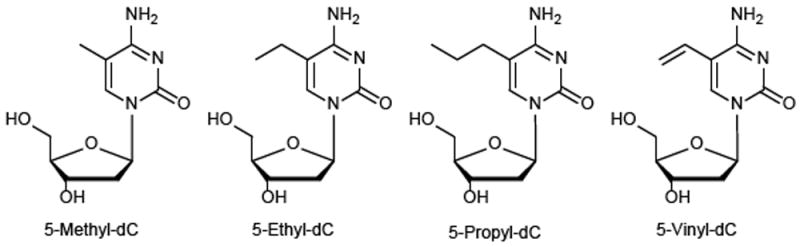

The goal of the present work was to probe the ability of C5-alkylated cytosines with extended side chain to direct DNMT1-catalyzed DNA methylation. The novel C5-alkyl-cytosine analogs (5-ethyl-dC, 5-propyl-dC, and 5-vinyl-dC, Scheme 1) were placed within a CpG site representing codon 157 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene, and the resulting synthetic DNA duplexes were incubated with human recombinant DNMT1 protein. A mass spectrometry based assay was used to study the kinetics of cytosine methylation in the presence of native MeC and its homologues with extended C5 alkyl chain. DNMT1 complexes with structurally modified DNA were investigated using molecular modeling.

Scheme 1.

Structures of MedC, EthyldC, PropyldC and VinyldC

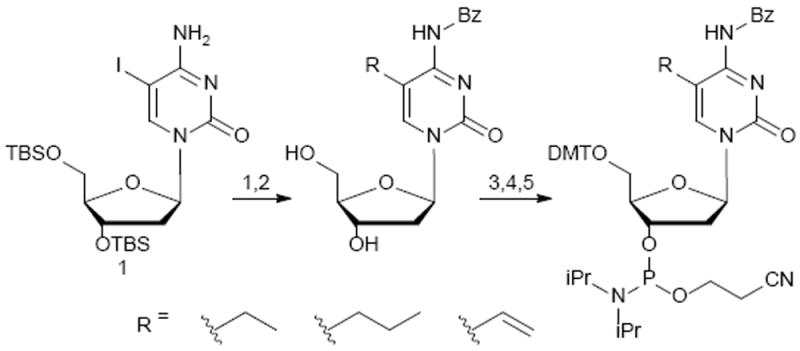

In order to incorporate 5-ethyl-dC, 5-propyl-dC, and 5-vinyl-dC into DNA strands, the corresponding nucleoside phosphoramidites were synthesized. The key starting material for the synthesis of these phosphoramidites was TBS-protected-5-iodo-dC (5-I-dC, 1 in Scheme 2).12, 13 5-I-dC was subjected to Sonogashira and Stille cross- coupling reactions to introduce ethyl, propyl, or vinyl groups at the C-5 of dC (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of nucleoside phosphoramidites of EthyldC, PropyldC and VinyldC. 1. Ethyl(i) TMS acetylene, Pd(PPh3)4, CuI, anh. DMF, 48h r.t. (ii) 1 N KOH, anh. MeOH, 3 hrs r.t. (iii) 10% Pd-C, H2 (1atm), 24 hrs at r.t. Propyl(i) propyne (5 psi), Pd(PPh3)4, eq CuI, anh. DMF, 24 h at r.t. (ii) 10% Pd-C, anh. MeOH, H2 (1 atm), 24 hrs at r.t. Vinyl(i) tributylvinyl tin, Pd2(dba)3, tri(2-furanyl)phosphine, anh. 1-methyl-2-pyrolidinone, 24 hrs 60 °C 2. PhCOCl, anh. pyridine, overnight, r.t. 3. Et3N•3HF, anh. DCM, 16h 4. DMTrCl, anh. pyridine, 16h 5. 2-Cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchloro phosphoramidite, DIPEA, anh. DCM, 16h, r.t.

C5-ethyl and propyl groups on cytidine were introduced by Sonogashira cross-coupling of compound 1 with TMS-protected acetylene or propyne gas, respectively (Scheme 2 and ESI for details). The reactions were conducted in the presence of tetrakis(triphenyl-phosphine)palladium(0) at room temperature.14, 15 The C-5 vinyl group was introduced via Stille coupling between 1 and tributylvinyltin in presence of palladium catalyst (Scheme 2). TBS-protected 5-ethyl-dC, 5-propyl-dC, and 5-vinyl-dC nucleosides were converted to the corresponding phosphoramidites to enable their incorporation into DNA strands (Scheme 2). All intermediates and final compounds were structurally characterized by a combination of 1H,13C,31P-NMR, HRMS, and MS/MS (see ESI, Figures S1-S18).

The novel C5-functionalized dC phosphoramidites were used in solid phase synthesis to generate oligodeoxynucleotide 19-mers 5′-CGCGGA[alkyl-C]GCGGGT GCCGGG-3′ representing codons 155-160 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene (Table S1). In the resulting DNA duplexes (Table S2), structurally modified cytosine is base paired with guanine at the first position of p53 codon 157, a prominent mutational “hotspot” in cancer.16 All DNA strands were purified by reverse phase HPLC and characterized by ESI--MS (Table S1 and Figures S19-S21).17, 18

To obtain double stranded DNA, synthetic strands containing MedC analogues were annealed to their compliments (Table S2). The duplexes were characterized by circular dichroism spectroscopy and thermal melting curves (Figure S21 and Table S2).18-20 These data indicated that the presence of the C5-alkylated cytidine analogs did not alter the overall secondary structure of the DNA duplexes.

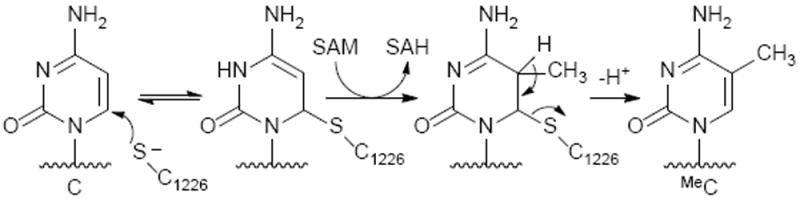

In cells, 5-methyl-dC at a hemimethylated CpG sites directs DNMT1 mediated DNA methylation of cytosine in the opposite strand. Following DNMT1 binding to hemimethylated DNA via the target recognition domain (TRD) of the protein, the cytidine to be methylated is flipped out of the duplex to enter the protein active site. The thiolate of the active site cysteine (C1226) forms a covalent bond with C-6, thereby activating the C5 position for methyl transfer from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). Base catalyzed removal of the C5 proton allows for re-aromatization and the release of the newly formed MeC (Scheme 3).21, 22

Scheme 3.

DNMT1 reaction mechanism.

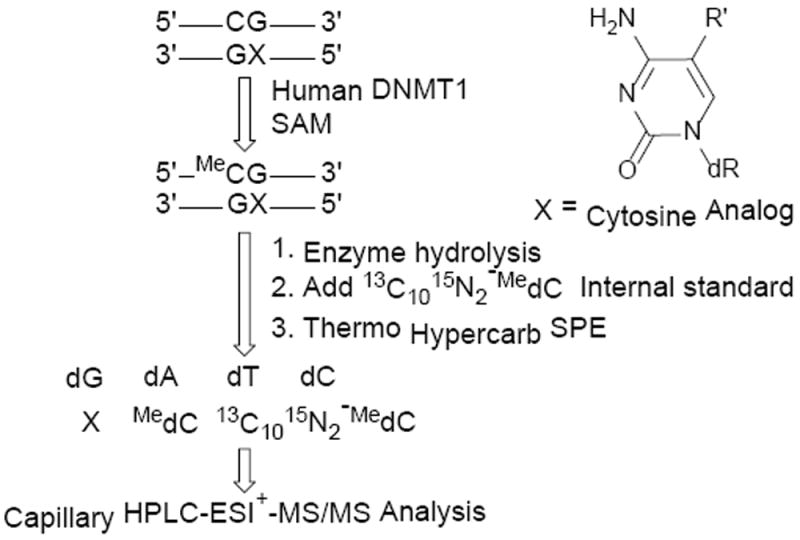

To determine whether C-5 alkylcytosines with extended alkyl chain length are able to direct DNMT1 mediated cytosine methylation, DNA methylation assays were conducted with recombinant human DNMT1 and structurally modified duplexes containing 5-ethyl-dC, 5-propyl-dC, and 5-vinyl-dC in a CpG sequence opposite unsubstituted dC (Scheme 4). 5-methyl-dC was employed as a positive control, while dC served as a negative control. Following incubation of DNMT1 and DNA duplexes with SAM and DNMT buffer, isotope dilution HPLC-ESI-ESI-MS/MS assay developed in our laboratory (Scheme 4) was employed to quantify the extent of DNMT1-mediated methyl transfer.

Scheme 4.

Mass spectrometry based assay to quantify DNMT1-mediated methyl transfer.

To quantify DNA methylation amounts, DNA was enzymatically digested to the corresponding 2′-deoxy-nucleosides and spiked with 13C1015N2-MedC internal standard, followed by solid phase extraction (SPE) (Scheme 4). MedC was quantified by isotope dilution HPLC ESI+-MS/MS using selected reaction monitoring of m/z 242.1 [M + H+] → m/z 126.1 [M – deoxyribose + H+] for MeC and m/z 254.1 [M + H+] → m/z 133.2 [M − deoxyribose + H+] for 13C1015N2-MedC internal standard (Figure 1). The amounts of newly formed MeC were calculated from HPLC ESI+-MS/MS peak areas amounts, followed by subtraction of the background values present in no enzyme controls.

Figure 1.

HPLC-ESI-MS/MS detection of 5-methyl-dC.

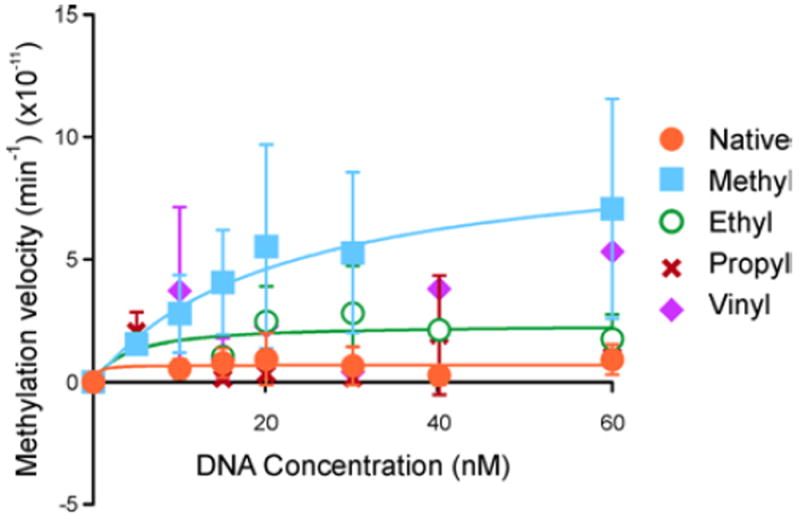

Data were fitted into Michaelis-Menten curves to allow for kinetic analyses (Figure 2). The Vmax and Km values were determined via nonlinear regression using data from three or more individual points.23 As anticipated, no DNMT1 mediated methylation was observed for DNA duplexes containing unmodified C:G base pair, while 5-MedC containing DNA was efficiently methylated (Figure 2). 5-ethyl-dC containing DNA was recognized as a DNMT1 substrate, although the Vmax value was significantly reduced as compared to the native substrate (2.4 × 10-2 nM/min vs 9.6 × 10-2 nM/min, respectively, p = 0.017) (Figure 2, Table S3). The corresponding Km values were 21.8 ± 13.7 and 3.90 ± 6.42 nM, for 5-methyl-dC and 5-ethyl-dC, respectively. In contrast, neither PropylC nor vinylC were able to direct DNA methylation under the conditions tested (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Michaelis-Menten plots showing activity of human DNMT1 toward DNA containing 5-alkyl-dC analogs (Sequence: 5′-CGCGGA[alkyl-C]GCGGGTGCCGGG-3′). The error bars represent the standard deviation of at least N = 3 repeats.

Overall, our data suggests that the increase in steric bulk at C-5 by extending the alkyl chain length hinders DNMT1 enzyme activity. Although DNMT1 is able to recognize and methylate the DNA sequence containing 5-ethyl-dC, duplexes containing 5-propyl-dC are poor DNMT1 substrates (Figure 2). Valinluck et al. previously reported that DNMT1 was capable of accommodating DNA duplexes containing 5-chloro-dC, 5-bromo-dC, and iodo-dC.8 In contrast, oxidation of MeC to 5-hydroxymethyl-dC, 5-formyl-dC, and 5-carboxyl-dC hindered DNMT1 activity.11 In addition, 5-vinyl-dC containing duplex was not a substrate for DNMT1 (Figure 2).

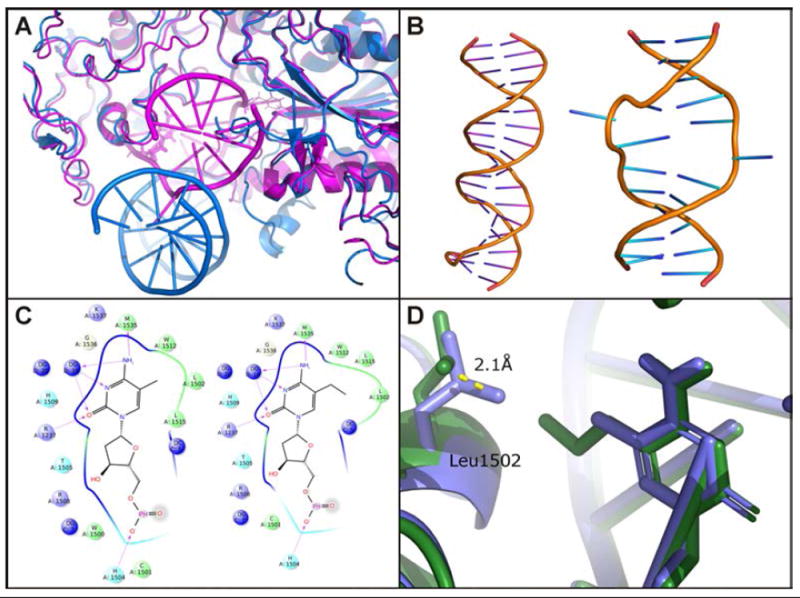

To determine whether the observed decrease in DNMT1 activity is associated with altered protein binding to structurally modified DNA, molecular modeling studies were conducted. Published crystal structures reveal two distinct modes of DNMT1 binding to DNA: the inactive one corresponding to protein complex with unmethylated (PDB: 3PTA) and the active DNMT1 complex with hemi-methylated (PDB: 4DA4) (Figure 3A).21, 24 The catalytically productive DNMT1-DNA complex is characterized by a large helical distortion around the central hemi-mCpG site, leading to duplex opening and nucleotide flipping (Figure 3B). To understand the effects of increasing C5-alkyl chain length on DNMT1 activity, homology models of the productive hDNMT1 complex with hemi-methylated DNA or its extended chain homologues was created.25, 26 A localized energy minimization encompassing all amino acid residues within 15 Å of the modified bases was performed to determine how the increased length of the alkyl chain influences the recognition of hemi-methylated CpG sites in DNA by the methylase.

Figure 3.

A. Crystal structures of DNMT1 bound to methylated DNA (magenta)21 or unmethylated DNA (blue)24 reveal two distinctive binding orientations. B. Hemi-methylated DNA in the productive DNMT1 complex undergoes a large helical distortion. C. Excessive steric bulk from growing C5 alkyl chain distorts the MeC recognition pocket. D. PropylC causes a 2.1 Å shift in the position of L1502.

Within the productive hDNMT1-DNA complex, the target recognition domain (TRD) consists of a hydrophobic concave surface consisting of C1505, L1502, L1515, and M1535.21 This pocket harbors the 5-methyl group of MeC and is involved in the recognition of the hemi-methylated MeCpG. We found that extension of the C5-alkyl chain disrupts DNA binding within the shallow hydrophobic pocket of the TRD due to the added steric bulk (Figure 3C). This distortion leads to a 2.1 Å displacement of L1502 in the case of 5-propyl-dC (Figure 3D) and 1.4 Å for 5-ethyl-dC. Although the degree of L1502 displacement in the presence of 5-vinyl-dC (1.4 Å) is similar to that of EthylC, the reduced DNMT1 activity in the case of VinylC can be explained by the loss of rotational freedom in the presence of the unsaturated bond within the C5 substituent on cytosine.

Our model supports the kinetic data shown in Figure 2 and Table S3, with the Km values reflecting either a productive or unproductive mode of DNMT1 binding. The lowest Km value (0.450 nM, Table S3) is observed for DNA containing unsubstituted cytosine, suggesting tighter binding within an unproductive DNMT1-DNA complex. In contrast, the productive DNMT1-DNA complex is hallmarked by a large distortion in the DNA duplex and mode of binding, resulting in a lower Km value (21.8 nM for MeC, see Table S3). As the length of the C5-alkyl chain increases, structural disruption in the target recognition domain (TRD) forces the enzyme to adopt an unproductive mode binding characterized by a lower Km value.

In summary, we have synthesized DNA duplexes containing a range of 5-alkyl-dC analogues with extended side chain. These unnatural DNA substrates were used to explore the ability of DNMT1 protein to recognize and methylate CpG sequences containing C5-alkylcytosine modifications with extended alkyl chain. The enzyme was capable of recognizing and methylating DNA duplexes containing MeC and EthylC with similar efficiencies, indicating that the ethyl group can be tolerated. In contrast, DNMT1 showed no enzymatic activity towards VinylC and PropylC containing duplexes under the conditions tested (Figure 3). We hypothesize that DNMT1 can bind to DNA to form two distinct complexes: an inactive conformation characterized by tighter binding and a lower affinity active conformation. Moreover, molecular models of DNMT1-DNA interactions indicate that the presence of larger C-5 alkyl chains at dC disrupt the integrity of the DNA recognition pocket, with PropylC pushing DNMT1 conformation toward the inactive protein-DNA complex. Although EthylC and VinylC cause a similar disruption of the DNA recognition pocket, only EthylC containing duplex is a substrate for DNMT1-catalized methylation, suggesting that the presence of a C-5 vinyl group on cytosine affects other steps within the DNMT1 catalytic cycle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Cancer Institute (R01 CA095039-02). J.F. was partially supported by the NIH Chemical Biology Interface Training Grant (5 T32 GM 8700-18).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details for chemical synthesis, kinetic determination, molecular modelling, and HPLC and MS data and spectra. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

The authors attest there are no conflicts of interest.

Notes and references

- 1.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrich B, Bird A. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6538–6547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klose RJ, Bird AP. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylin SB, Jones PA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goll MG, Bestor TH. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacinto FV, Esteller M. Mutagenesis. 2007;22:247–253. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gem009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valinluck V, Sowers LC. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5583–5586. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valinluck V, Sowers LC. Cancer Res. 2007;67:946–950. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valinluck V, Liu P, Kang JI, Jr, Burdzy A, Sowers LC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3057–3064. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji D, Lin K, Song J, Wang Y. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:1749–1752. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00150h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robins MJ, Barr PJ, Giziewicz J. Can J Chem. 1982;60:554–557. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins MJ, Barr PJ. J Org Chem. 1983;48:1854–1862. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonogashira K. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2002;653:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Tetrahed Lett. 1975;16:4467–4470. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denissenko MF, Chen JX, Tang MS, Pfeifer GP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3893–3898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matter B, Wang G, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:731–741. doi: 10.1021/tx049974l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Upadhyaya P, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Biochemistry. 2004;43:540–549. doi: 10.1021/bi035259j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegel R, Shallop A, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:541–550. doi: 10.1021/tx025619o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tretyakova N, Matter B, Jones R, Shallop A. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9535–9544. doi: 10.1021/bi025540i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song J, Teplova M, Ishibe-Murakami S, Patel DJ. Science. 2012;335:709–712. doi: 10.1126/science.1214453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Lior-Hoffmann L, Wang S, Zhang Y, Broyde S. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2828–2838. doi: 10.1021/bi400163k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gromova ES, Subach OM, Baskunov VB, Geacintov N. In: Structural Biology of DNA Damage and Repair. Stone MP, editor. ch. 7. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2010. pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song J, Rechkoblit O, Bestor TH, Patel DJ. Science. 2011;331:1036–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1195380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickramaratne S, Ji S, Mukherjee S, Su Y, Pence MG, Lior-Hoffmann L, Fu I, Broyde S, Guengerich FP, Distefano M, Scharer OD, Sham YY, Tretyakova N. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:23589–23603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.745257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Maddali K, Pommier Y, Sham YY, Wang Z. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3275–3279. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.