Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a world-wide healthcare problem, resulting in increased cardiovascular mortality and often leading to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) where patients require kidney replacement therapies such as hemodialysis or kidney transplantation. Loss of functional nephrons contributes to the progression of CKD, which can be attenuated but not reversed due to inability to generate new nephrons in human adult kidneys. Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), by virtue of their unlimited self-renewal and ability to differentiate into cells of all three embryonic germ layers, are attractive sources for kidney regenerative therapies. Recent advances in stem cell biology have identified key signals necessary to maintain stemness of human nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) in vitro, and led to establishment of protocols to generate NPCs and nephron epithelial cells from human fetal kidneys and hPSCs. Effective production of large amounts of human NPCs and kidney organoids will facilitate elucidation of developmental and pathobiological pathways, kidney disease modeling and drug screening as well as kidney regenerative therapies. We summarize the recent studies to induce NPCs and kidney cells from hPSCs, studies of NPC expansion from mouse and human embryonic kidneys, and discuss possible approaches in vivo to regenerate kidneys with cell therapies and the development of bioengineered kidneys.

Keywords: pluripotent stem cell, kidney, organoid, nephron, regenerative medicine, differentiation

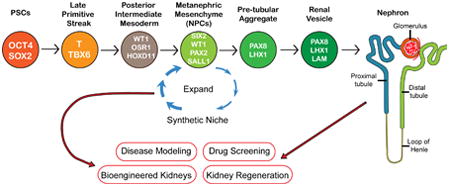

Graphical abstract

Recent advances in stem cell biology have identified key signals necessary to maintain stemness of human nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) in vitro, and led to establishment of protocols to generate NPCs and nephron epithelial cells from hPSCs. Effective production of human NPCs will facilitate elucidation of developmental pathways, kidney disease modeling and drug screening as well as kidney regenerative therapies.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 9-14% of the U.S. adult population [1]. CKD is one of the most important independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease [2, 3]. Loss of functional nephrons and the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis contribute to the progression of CKD, which can be attenuated but not reversed. While adult kidneys possess an intrinsic capacity to self-repair following injury [4], the process of nephrogenesis, the formation of new nephrons, is limited to the period of embryonic development in humans. Thus, the loss of nephrons is permanent and ultimately often leads to end stage renal disease (ESRD) where patients require renal replacement therapies such as hemodialysis associated with significantly increased mortality and morbidity [5]. In addition the paucity of disease models using human tissue has likely contributed to the paucity of therapeutics for acute and chronic kidney diseases.

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), by virtue of their unlimited self-renewal and ability to generate cells of all three germ layers of the embryo [6, 7], are ideally suited for the derivation of nephron progenitor cells (NPCs), functional human kidney cells and tissues. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be readily generated from patients with kidney disease [7, 8], enabling the development of immunocompatible tissues as well as patient-specific models of disease. However, the protocol for differentiation into kidney lineage cells has eluded many investigators over the years.

Significant advances have been made within the past decade that have drawn upon our knowledge of kidney development to differentiate mouse and human PSCs into cells of kidney lineages [6, 9-21]. Directed differentiation approaches mimicking kidney development in vivo have resulted in generation of NPCs and kidney-like tissue (kidney organoids) from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and hiPSCs [6, 15-19]. These advances represent novel approaches toward establishment of kidney regenerative therapies and disease modeling.

In this review, we summarize the current literature dealing with the differentiation of PSCs into NPCs and kidney organoids. We also review current methodologies to expand NPCs derived from embryonic kidneys of mice and humans, or hPSCs, in order to obtain sufficient number of cells. In addition, we discuss potential approaches to use of these cells.

Generation of Nephron Progenitor Cells

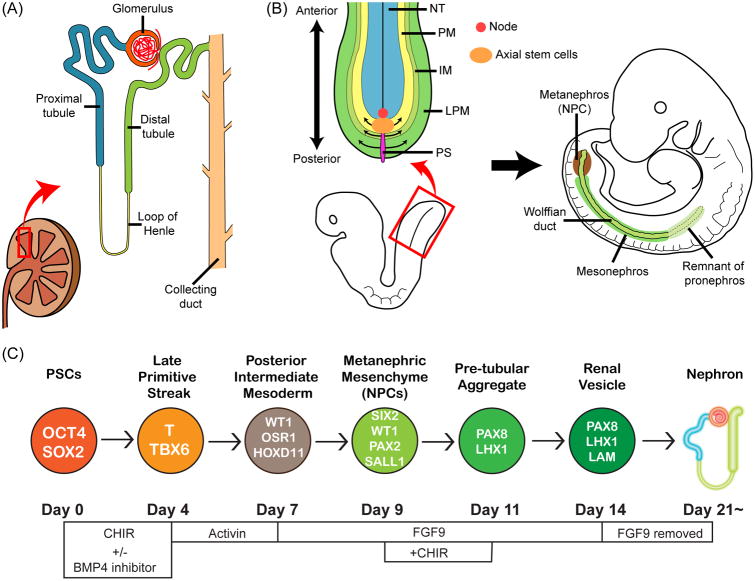

The kidney consists of many different cell types including various components of the nephron, vasculature and interstitial stromal cells. In the normal kidney nephron epithelial cells occupy >90% of kidney cortex. The nephron is the functional unit of the kidney, and consists of a structure responsible for filtration (a glomerulus) and a multi-segmented tubule which is responsible for selective reabsorption and secretion of a large number of solutes (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A differentiation protocol of hPSCs into NPCs and kidney organoids.(A) An illustration showing structures of a kidney. (B) A schematic illustration showing mesoderm formation from primitive streak (PS). Primitive streak cells differentiate into paraxial mesoderm (PM), intermediate mesoderm (IM), and lateral plate mesoderm (LPM). NT: neural tube. (C) A schematic illustration showing the differentiation protocol into NPCs (nephron progenitor cells) and kidney organoids that we have published [19, 42]. At each stage proteins that identify that stage are identified in the circles: OCT4: POU class 5 homeobox 1. SOX2: SRY-box 2. T: brachyury. WT1: Wilms tumor 1. OSR1: odd-skipped related transcription factor 1. HOXD11: homeobox D11. SIX2: SIX2 homeobox 2. PAX2: paired box 2. SALL1: spalt like transcription factor 1. PAX8: paired box 8. LHX1: LIM homeobox 1. LAM: laminin.

NPCs can be identified by the expression of a transcriptional factor, Six2, in mouse embryos [22]. Six2+ NPCs are multipotent and can differentiate into multi-segmented nephron epithelial cells including podocytes and parietal epithelial cells of the glomerulus, and epithelial cells of the proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules. Six2+ NPCs also possess the ability to self-renew in their cap mesenchyme niche in embryonic kidneys [22]. NPCs can be an attractive source for kidney regenerative medicine as well as kidney disease modeling in vitro. There are currently two major approaches to obtain human NPCs. The first approach is to purify NPCs from human fetal kidneys using cell surface markers. Dekel and colleagues characterized stem cell markers in human fetal kidneys and identified nephron progenitor cell surface markers, namely NCAM1 and FZD7, which enabled the purification of an enriched cell population of human NPCs [23, 24]. Dekel et al. also demonstrated that purified NCAM1+/CD133- cells cultured in serum-free media were enriched for SIX2+ NPCs, though those cells quickly differentiated in serum-free media within a week [25]. A recent study from the same group showed at single-cell resolution a preservation of uninduced and induced cap mesenchyme as well as a transitioning mesenchymal-epithelial state by dissection of NCAM+/CD133- progenitor cells according to EpCAM expression levels [26]. In addition, Dekel et al. demonstrated that NCAM+ cells derived from human fetal kidneys can differentiate into kidney tubular structures and halt the deterioration of kidney function when administered to mice that had undegone 5/6 nephrectomy [27].

The second approach to the generation of human NPCs is direct differentiation of hPSCs. Although Six2 identifies NPCs in embryonic kidneys, Six2 expression was also detected in the developing head, ear, and limb [22, 28]. Since hPSCs can differentiate into any type of tissues, one approach to the generation of kidney tissue is directed differentiation in vitro guided by characteristics of kidney development in vivo in order to achieve specific differentiation into SIX2+ NPCs without contamination of other lineage cells.

Kidneys arise from the intermediate mesoderm; however, the precise site of origin of functional kidneys, the metanephros, has not been clearly defined in the intermediate mesoderm due to complexity of kidney development in humans. Three different kidney tissues, namely pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros develop during mammalian embryonic development (Fig. 1B). Although pronephros and mesonephros form primitive nephrons, the metanephros becomes the functional kidney while the pronephros and mesonephros degrade during embryonic development. Taguchi et al. used lineage tracing techniques in mice to identify the precise origin of the metanephros, and found that the metanephros originated from the posterior area of the intermediate mesoderm where Pax2 and Lim1 (LHX1 in humans) were not expressed [16]. WhilePax2 and Lim1 have been used to identify the intermediate mesoderm in mouse embryos [29, 30] and have been used as markers of progenitors of kidney lineages in published studies where kidney tubular-like cells were generated from hPSCs [15, 17, 31] this Pax2+Lim1+ population did not yield a high percentage of Six2+ cells. Xia et al. demonstrated that induction of PAX2+LHX1+ intermediate mesoderm cells from hPSCs resulted in an enrichment of ureteric bud progenitor-like cells, but not NPCs [31]. Studies of Takasato and our group generated lotus tetragonolobus lectin (LTL)-positive proximal tubular-like cells from hPSCs via induction of PAX2+LHX1+ intermediate mesoderm cells; however, the induction efficiency of SIX2+ nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) from those PAX2+LHX1+ cells was low (∼20%) [15, 17]. These findings were consistent with the Taguchi et al. study which redefined the origin of metanephros in Osr1+Wt1+Pax2-Lim1- posterior intermediate mesoderm in mice. We extrapolated from this important study that the directed differentiation of hPSCs to OSR1+WT1+PAX2-LHX1- posterior intermediate mesoderm cells would facilitate their differentiation into NPCs, which do express PAX2, and subsequently further differentiate into metanephros tissue.

Mesoderm tissues, including the intermediate mesoderm, arise from the primitive streak [32]. The primitive streak is a structure that forms in the blastula during early stages of mammalian embryos, and appears as an elongating groove at the caudal (or posterior) end of the embryo [33]. The cells migrate from the primitive streak anteriorly and form mesoderm tissues from the paraxial to lateral plate mesoderm. Importantly, the cell locations in the primitive streak define the subsequent differentiation into paraxial or lateral plate mesoderm (Fig. 1B) [34, 35]. Indeed, the cells located at the anterior part of the primitive streak differentiate into paraxial mesoderm while the posterior cells in the primitive streak become the lateral plate mesoderm. The intermediate mesoderm lies between the paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm, and its progenitor cells are located at the central region of the primitive streak.

Cells migrate from the primitive streak anteriorly, and form mesoderm tissues from the anterior part of embryos towards the posterior (Fig. 1B) [36]. Thus, the cells that migrate from the primitive streak at earlier stages of embryonic development subsequently differentiate into the more anterior mesoderm and those that migrate from the late stage of the primitive streak subsequently form the posterior mesoderm. Taguchi et al. also showed consistent results using lineage tracing techniques to track the subsequent differentiation of Brachyury (T)+ primitive streak cells at different stages of embryonic development [16]. They found that T+ primitive streak cells at E7.5 of mouse embryos form the anterior intermediate mesoderm and subsequently differentiate into Wolffian ducts while T+ primitive streak cells at E8.5 form the posterior intermediate mesoderm and differentiate into the metanephric mesenchyme (NPCs). Hence, to induce the posterior intermediate mesoderm, it would be the most efficient to induce the cells located at the central region of the late-stage primitive streak.

The gradient of Wnt3a and BMP4 patterns the anterior-posterior axis of the primitive streak. Higher levels of BMP4 induce the posterior primitive streak in chickens and mice [37, 38]; thus, adjusting the BMP4 signal level during the directed differentiation of hPSCs is important to induce cells mimicking those at the central region of the primitive streak, the origin of the intermediate mesoderm. Since there are no specific markers to identify those late-stage mid primitive streak cells during the directed differentiation of hPSCs in vitro, we tested for the best timing and treatment with WNT and BMP4 modulators by examining the subsequent differentiation into WT1+HOXD11+ posterior intermediate mesoderm cells from hPSCs [6, 19]. HOXD11, however, is also abundantly expressed in the lateral plate mesoderm [39]; therefore, we used co-expression of WT1, OSR1 and HOXD11 to specify the posterior intermediate mesoderm [19]. From our initial screening experiments, we found that longer treatment of hiPSCs with CHIR99021 (CHIR, a WNT activator) followed by differentiation with activin A is more effective in inducing HOXD11 expression. This finding was consistent with developmental studies using mice and chickens, as we discussed previously. The longer treatment with CHIR induced the later stage of primitive streak cells which subsequently form the posterior mesoderm, a sequence that mimics the anterior-posterior patterning of mesoderm in embryonic development in vivo.

Barak et al. demonstrated the important role of FGF9 and FGF20 in maintenance of the “stemness” of NPCs in mice and humans [40], and reciprocal interactions of the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric buds are key components of kidney development [41]. Both the metanephric mesenchyme and ureteric buds produce growth factors and promote the differentiation of each other. Barak et al. reported that reduction of FGF9 and FGF20 levels lead to loss of NPCs in mice. This study indicated critical roles of FGF signals in NPC differentiation and maintenance. FGF9 is produced by ureteric buds while FGF20 is produced in NPCs. This suggested that treatment with FGF9 might be required to induce NPCs from the posterior intermediate mesoderm cells derived from hPSCs, unless ureteric bud cells are simultaneously induced by the directed differentiation protocol and can generate FGF9. In our recent study, we used a low dose of FGF9 (10 ng/ml) to induce SIX2+SALL1+WT1+PAX2+ NPCs from WT1+HOXD11+ posterior intermediate mesoderm cells that had been derived from hPSCs [19]. Addition of FGF20 was not required, consistent with the Barak et al. study that showed FGF20 was produced by NPCs [40]. Efficient production of NPCs derived from hPSCs would facilitate cell therapies and development of bioengineered kidneys. In our published studies, we evaluated the induction efficiency at each step of differentiation with assays of multiple protein markers by immunostaining in order to follow in vivo kidney development through the posterior intermediate mesoderm induction. This resulted in a highly efficient (SIX2+ cells: up to 80-90%) and rapid (∼9 days) differentiation protocol from both hESCs and hiPSCs into SIX2+SALL1+WT1+PAX2+ NPCs (Fig. 1C) [6, 19]. These NPCs derived from hPSCs proved their multipotency by differentiating into multi-segmented nephron structures with characteristics of podocytes, proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and distal tubules. There are currently four different protocols to generate kidney organoids from hPSCs [16, 18, 19, 42, 43]. For discussion about differentiation markers and differences of generation approaches and organoid characteristics, see our recent reviews [21, 44]. Published studies characterized cells in kidney organoids at some level, yet further studies will be required to fully understand the functionalities of kidney organoids generated with different approaches.

Expansion of Nephron Progenitor Cells

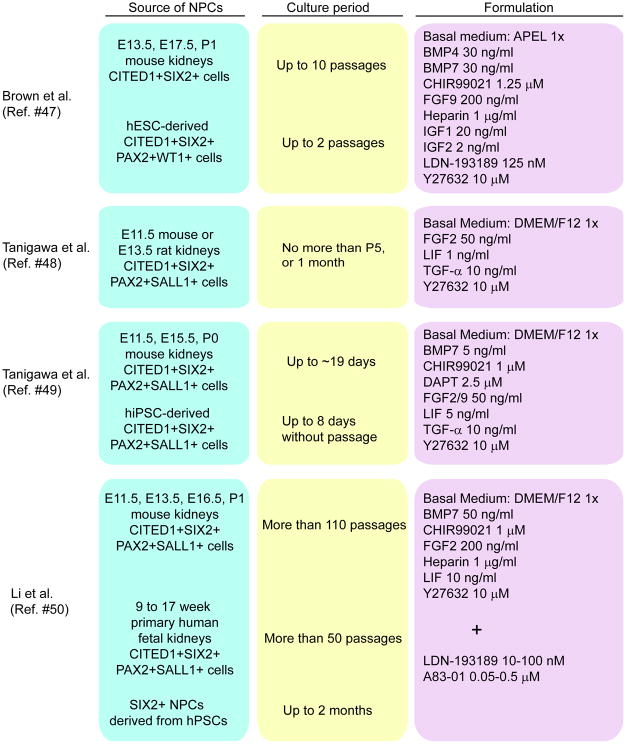

It is important to establish methods to expand NPCs for potential medical applications including cell therapy, disease modeling, drug screening, and reconstitution of the kidney where large numbers of cells are required [45]. The mammalian kidney develops by radial addition of new nephrons that form at the outermost cortex within a progenitor cell niche known as the nephrogenic zone [46]. Recently, other groups reported methods to maintain stemness of NPCs by creating a synthetic niche. These groups used mouse or rat embryonic kidneys as a source of NPCs [47-50] (Fig. 2). Brown et al. isolated Cited1+ NPCs by flow sorting after dissociation of embryonic kidneys of the Cited1creERT2-EGFP mouse strain [47]. On the other hand, Tanigawa et al. and Li et al. purified Six2-GFP+ cells as NPCs by FACS after dissociation of embryonic kidneys of the Six2tm3(EGFP/cre/ERT2)Amc transgenic mouse [48-50].

Figure 2.

Methods to expand NPCs isolated from mouse and human embryonic kidneys or generated from hPSCs. Sources of NPCs, culture period, and formulation of media are listed. CITED1: Cbp/p300 interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp rich carboxy-terminal domain 1. SIX2: SIX2 homeobox 2. PAX2: paired box 2. WT1: Wilms tumor 1. SALL1: spalt like transcription factor 1. BMP: bone morphogenetic protein. FGF: fibroblast growth factor. IGF: insulin0like growth factor. LDN-193189: 4-[6-[4-(1-Piperazinyl)phenyl]pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]-quinoline hydrochloride. Y27632: (R)-(+)-trans-4-(1-Aminoethyl)-N-(4-Pyridyl) cyclohexanecarboxamide dihydrochloride. LIF: leukemia inhibitory factor. TGF: transforming growth factor. CHIR99021: 6-[[2-[[4-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-5-(5-methyl-1H-imidazol-2-yl)-2-pyrimidinyl]amino]ethyl]amino]-3-pyridinecarbonitrile. DAPT: N-[(3,5-Difluorophenyl)acetyl]-L-alanyl-2-phenyl]glycine-1,1-dimethylethyl ester. A83-01: 3-(6-Methyl-2-pyridinyl)-N-phenyl-4-(4-quinolinyl)-1H-pyrazole-1-carbothioamide.

These groups also generated NPCs from hPSCs or isolated NPCs from human fetal kidneys in an attempt to maintain their stemness in their synthetic niche environments [47, 49, 50]. Brown et al. used BMP4, BMP7, CHIR99021, FGF9, IGF1/2 and Y27632 (a selective p160ROCK inhibitor), and Tanigawa et al. used BMP7, CHIR99021, DAPT (N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]- S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester, a Notch inhibitor). FGF2/9, LIF, transforming growth factor (TGF)-α and Y27632 were used as in vitro niche signaling factors [47, 49]. These NPCs derived from hPSCs expressed Cited1, Six2, Pax2 and Sall1 as NPCs-specific marker genes and fulfilled functional criteria such as in vitro differentiation into multi-segmented nephron epithelial cells. However, these groups reported only limited expansion (2 passages or 8 days culture) of these NPCs. Therefore it is difficult to use these NPCs for potential medical applications because culture conditions for long-term self-renewal of NPCs have yet to be achieved. A recent study from Li et al. used BMP7, CHIR99021, FGF2, LIF and Y27632 as in vitro niche signaling factors [50]. NPCs generated by this group expressed NPC-specific marker genes (Cited1, Six2, Pax2 and Sall1), had in vitro differentiation abilities, and were able to be cultured for long periods of time (>50 passages) in 3D culture. However, in contrast to the other two groups, this group used human fetal kidneys as a source of NPCs. Pode-Shakked et al. prospectively isolated NPCs from human fetal kidneys grown in culture [26]. This group initially used a similar medium as Brown et al. to culture human fetal kidneys. Following expansion of human fetal kidneys they used a cell surface marker combination comprised of NCAM, EpCAM and CD133 to sort out cell fractions from expanded human fetal kidney cultures and showed at single-cell resolution a preservation of uninduced and induced cap mesenchyme (NCAM+CD133-EpCAM- cells) as well as a transitioning mesenchymal-epithelial state that emerges as NCAM+CD133-EpCAMdim cells [26, 50]. Li et al. also attempted to derive human NPCs from hiPSCs. They could not induce NPCs with high efficiency; however, SIX2+ NPCs were successfully purified from a SIX2-GFP reporter line after differentiation with a previously published protocol [50]. Although co-culture with mouse embryonic spinal cord was required to differentiate NPCs into nephron epithelial cells, their combination of growth factors and small molecules allowed them to maintain SIX2+ NPCs derived from hiPSCs for 2 months in 3D culture. Of note, addition of SMAD inhibitors, LDN193189 and A83-01, was required when authors expanded human NPCs rather than mouse NPCs, suggesting there are important differences between human and mouse differentiation factors [50].

Protocols that require co-cultures with mouse embryonic spinal cord to generate kidney organoids may hinder medical applications involving cell therapy, drug screening and reconstitution of the kidney because the number of samples will be limited due to the need to collect mouse embryonic spinal cord. Moreover, the use of mouse embryonic spinal cords with their undefined components (such as growth factors) represents a limitation in disease modeling and mechanistic analysis. Indeed, these undefined components might affect disease phenotypes in kidney organoids derived from patients with genetic kidney disease. Despite these limitations, these recent studies to expand NPCs will inform the development of methods which will hopefully lead to the generation of large amounts of NPCs for studies of drug screening, kidney regeneration and/or development of kidney function replacement devices.

Cell Therapies with Nephron Progenitor Cells

NPCs derived from hPSCs would be attractive sources for cell therapies. There have been few published reports, however, that demonstrate therapeutic efficacy of cell therapy with NPCs generated from hiPSCs. Toyohara et al. have reported that cell therapy using OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs derived from hiPSCs ameliorates acute kidney injury (AKI) induced by ischemia/reperfusion in mice [51]. AKI is a syndrome characterized by the rapid loss of the kidney's excretory function and is typically diagnosed by the accumulation of end products of nitrogen metabolism (urea and creatinine) or decreased urine output. AKI can progress to CKD [52, 53]. Toyohara et al. established a multistep protocol for differentiating hiPSCs into OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs. First, the authors induced mesendoderm cells from hPSCs using a combination of 100 ng/ml activin A and 1 μM CHIR99021 for 2 days [13]. To differentiate mesendoderm cells toward the intermediate mesoderm, mesendoderm cells were then cultured with a medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml recombinant human BMP7 and 1 μM CHIR99021. After 3 days, the medium was changed to the medium supplemented with 1 μM TTNPB and 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. After 5 days, the medium was switched to the medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 and 0.5 μM dorsomorphin homolog (DMH) 1 to differentiate intermediate mesoderm cells to OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs. These OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs derived from hiPSC cells were capable of reconstituting three-dimensional proximal renal tubule-like structures.

Some OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs integrated into the host kidneys and then assumed some characteristics of proximal tubular cells when OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs were transplanted into the kidney parenchyma of mice with AKI induced by ischemia/reperfusion. However, this engraftment did not result in any obvious improvement of kidney function. On the other hand, transplantation of OSR1+SIX2+ NPCs into the renal capsule in the AKI mice model resulted in beneficial effects on renal function, with reduction in the elevation of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels and attenuated histopathological changes, such as tubular necrosis, tubule dilatation with casts, and interstitial fibrosis although there was no evidence of new nephron formation from transplanted NPCs [51]. Therefore, the improvement of kidney function was thought due to paracrine effects of renoprotective factors produced by transplanted NPCs. This is similar to findings in other cell therapy studies using mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), where renoprotective effects of intravenous cell infusion were described in animal models of kidney injury [54-58]. In fact, a recent phase 1/2A clinical study in humans showed some beneficial effects of MSCs infusion on kidneys in various clinical settings including transplantation with beneficial effects often attributed to immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory paracrine actions [59, 60]. By contrast, other studies in humans have found no beneficial effects (http://celltrials.info/2015/01/04/failures-2014/). It is possible that cell therapy using NPCs might generate renoprotective factors but a significant amount of further studies are required to develop cell therapy approaches that would be effective in generation of new nephrons or expansion of tubule compartments in kidneys in vivo. In addition, careful attention to quality control and robust reproducibility and genetic stability of NPCs must be attributes of protocols which could result in safe cellular sources for clinical use. A warning along these lines has been published in recent studies demonstrated P53 mutations in hPSCs [61, 62].

Future Directions Toward Kidney Regeneration

There are many challenges to using organoids to generate functional bioengineered kidney tissues [63], and one of the challenges relates to vascularization. Vascularization of kidney organoids needs to be induced in an organized way to direct blood flow from arteries and then drain into venous structures. In one study, the authors generated kidney buds by mixing human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), MSCs, and mouse embryonic kidney cells [64]. Kidney buds were then transplanted into a preformed cranial window of non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, and vascularized glomerular structures were observed with outgrowth of host mouse endothelial cells. Another study demonstrated vascularization of glomeruli when hPSC-derived podocytes were transplanted into mouse kidney subcapsular spaces [65]. Outgrowth of host mouse endothelial cells into the region of transplanted human podocytes was observed. However, capillary loops, an important structure of glomeruli facilitating blood filtration, were rarely formed. These transplantation experiments in vivo are encouraging; however, further studies to incorporate vascular systems into kidney organoids in vitro and/or in vivo will be required. Another challenge with organoids is the establishment of an effective drainage system for removal of blood filtrate after passage and processing through the tubule system.

Embryonic human and porcine kidney rudiments were previously explored as potential sources for kidney transplantation, yet functional maturation was not obtained in the mouse model [66]. Recently, blastocyst complementation has been applied to generate functional organs [67]. Blastocyst complementation is a technique in which the whole organs can be generated from donor PSCs using their chimera-forming ability to complement host animals which are deficient in organ development [68]. Usui et al. generated PSC-derived donor kidneys using Sall1-/- mice, which normally die soon after birth because of kidney agenesis of severe dysgenesis [69].

Another possible approach might be to use decellularized kidneys and then repopulate these cell-free structures to generate functional kidneys [70]. A method was developed to decellularize whole kidneys from rats, swine, and humans by perfusing detergent into the renal artery [71]. Decellularized rat kidney scaffolds were seeded with rat neonatal kidney cells (NKC) injected into the ureter, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) injected into the renal artery. Grafts produced rudimentary urine in vitro when perfused through their intrinsic vascular bed. The authors also transplanted the graft in an orthotopic position in rat, and reported production of urine through the ureteral conduit in vivo. Translation of this approach will clearly require further optimization of seeding methods to human-sized scaffolds as well as the establishment of protocols to ensure that the cells are delivered to the entire nephron.

3D bioprinting techniques would also be a potential approach to generate functional bioengineered kidneys. The Lewis lab has developed a bioprinting method to construct 3D tissues replete with vasculature, multiple cells types including proximal tubular cells, and an extracellular matrix [72, 73]. The 3D-printed tubular structure allows for perfusion of liquid into lumens lined with vascular or tubular cells [72-74]. This system can mimic blood flow and intratubular flow in vascular and tubular channels and can mimic the complex 3D structure of the proximal tubule.

Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip technology has been used to an in vitro model of the human kidney glomerulus. Musah et al. generated functional podocytes derived from hiPSCs, and developed a functional organ-on-chip microfluidic device that mimics the tissue–tissue interface and molecular filtration properties of the glomerular capillary wall by culturing hiPSCs-derived podocytes on one side of a porous flexible elastomer membrane lined with laminin with human kidney glomerular endothelial cells on the other side of the membrane in a microfluidic device [75]. Thus there are a large number of in vivo and in vitro models which may facilitate kidney disease modeling and drug screening as well as kidney regenerative therapies.

Conclusion

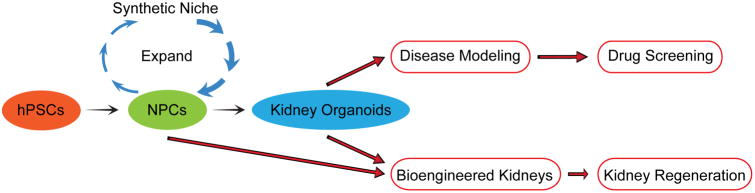

Significant advances have been made to develop novel sources to generate nephron progenitor cells and kidney organoids. Rapid and efficient differentiation protocols have been established to derive human NPCs from both hESCs and hiPSCs. This technology allows for the conversion of human somatic cells into human NPCs and kidney tissue, which will potentially lead to development of personalized medicine for kidney regeneration and creation of novel disease model systems using human tissue. Success in reliable and efficient expansion of human NPCs will contribute to development of methods for mass production of human NPCs, which can be then used for kidney disease modeling and high-throughput drug screening as well as kidney regenerative medicine (Fig. 3). In addition to approaches using NPCs many other novel approaches are being explored to create functional kidney tissue which can potentially replace current inadequate dialysis methods to treat the growing number of patients with end-stage kidney disease worldwide. Furthermore these approaches can provide human tissue models for disease so that new therapies can be developed to prevent and treat kidney diseases before they become very advanced.

Figure 3.

Future applications of NPCs and kidney organoids for drug screening and kidney regeneration. hPSCs: human pluripotent stem cells. NPCs: nephron progenitor cells.

Significance Statement.

Currently, there is no established treatment to regenerate nephrons in patients with CKD and ESKD. Recent studies have demonstrated the induction of nephron progenitor cells (NPCs) and differentiated kidney cells from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), providing novel sources for human disease modeling and potential kidney regeneration. Additionally, key signals important to expand NPCs from mouse embryonic kidneys have led to new insights into establishment of methods to create a synthetic niche for human NPCs. In this review, we summarize current protocols to generate and maintain NPCs from rodent and human PSCs and discuss development of a synthetic niche for NPCs and potential future applications of hPSCs to better understand acute and chronic kidney disease and develop new therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37 DK039773 and R01 DK072381 (to J.V.B.), the Uehara Memorial Foundation Research Fellowship for Research Abroad (to R.M.), a Grant-in-Aid for a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (to R.M.), a ReproCELL Stem Cell Research grant (to R.M.), a Brigham and Women's Hospital Research Excellence Award (to R.M.), a Brigham and Women's Hospital Faculty Career Development Award (to R.M.) a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Seed Grant (to R.M.), AJINOMOTO Co., Inc. (to R.M.), and Toray Industries, Inc. (to R.M.)

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: R.M., T.M. and J.V.B. wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interests: J.V.B. is a co-inventor on KIM-1 patents that have been licensed by Partners Healthcare to several companies. He has received royalty income from Partners Healthcare. J.V.B. and R.M. are co-inventors on patents (PCT/US16/52350) on organoid technologies that are assigned to Partners Healthcare. J.V.B. is a co-founder, consultant to, and owns equity in, Goldfinch Bio.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. Jama. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock JS, Gottlieb SS. Cardiorenal syndrome: new perspectives. Circulation. 2010;121:2592–2600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013;382:339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphreys BD, Valerius MT, Kobayashi A, et al. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. Excerpts from the US Renal Data System 2009 Annual Data Report. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010;55:S1–420. A426–427. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman BS, Lam AQ, Sundsbak JL, et al. Reduced ciliary polycystin-2 in induced pluripotent stem cells from polycystic kidney disease patients with PKD1 mutations. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:1571–1586. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D, Dressler GR. Nephrogenic factors promote differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into renal epithelia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2005;16:3527–3534. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce SJ, Rea RW, Steptoe AL, et al. In vitro differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells toward a renal lineage. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2007;75:337–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigneau C, Polgar K, Striker G, et al. Mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies generate progenitors that integrate long term into renal proximal tubules in vivo. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2007;18:1709–1720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morizane R, Monkawa T, Itoh H. Differentiation of murine embryonic stem and induced pluripotent stem cells to renal lineage in vitro. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;390:1334–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mae S, Shono A, Shiota F, et al. Monitoring and robust induction of nephrogenic intermediate mesoderm from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature communications. 2013;4:1367. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morizane R, Monkawa T, Fujii S, et al. Kidney specific protein-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells reproduce tubular structures in vitro and differentiate into renal tubular cells. PloS one. 2014;8:e64843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takasato M, Er PX, Becroft M, et al. Directing human embryonic stem cell differentiation towards a renal lineage generates a self-organizing kidney. Nature cell biology. 2014;16:118–126. doi: 10.1038/ncb2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taguchi A, Kaku Y, Ohmori T, et al. Redefining the in vivo origin of metanephric nephron progenitors enables generation of complex kidney structures from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam AQ, Freedman BS, Morizane R, et al. Rapid and efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intermediate mesoderm that forms tubules expressing kidney proximal tubular markers. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25:1211–1225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takasato M, Er PX, Chiu HS, et al. Kidney organoids from human iPS cells contain multiple lineages and model human nephrogenesis. Nature. 2015;526:564–568. doi: 10.1038/nature15695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morizane R, Lam AQ, Freedman BS, et al. Nephron organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells model kidney development and injury. Nature biotechnology. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nbt.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi S, Morizane R, Homma K, et al. Generation of kidney tubular organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Scientific reports. 2016;6:38353. doi: 10.1038/srep38353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morizane R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Organoids: A Translational Journey. Trends in molecular medicine. 2017;23:246–263. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi A, Valerius MT, Mugford JW, et al. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metsuyanim S, Harari-Steinberg O, Buzhor E, et al. Expression of stem cell markers in the human fetal kidney. PloS one. 2009;4:e6709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dekel B, Metsuyanim S, Schmidt-Ott KM, et al. Multiple imprinted and stemness genes provide a link between normal and tumor progenitor cells of the developing human kidney. Cancer research. 2006;66:6040–6049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pode-Shakked N, Pleniceanu O, Gershon R, et al. Dissecting Stages of Human Kidney Development and Tumorigenesis with Surface Markers Affords Simple Prospective Purification of Nephron Stem Cells. Scientific reports. 2016;6:23562. doi: 10.1038/srep23562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pode-Shakked N, Gershon R, Tam G, et al. Evidence of In Vitro Preservation of Human Nephrogenesis at the Single-Cell Level. Stem cell reports. 2017;9:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harari-Steinberg O, Metsuyanim S, Omer D, et al. Identification of human nephron progenitors capable of generation of kidney structures and functional repair of chronic renal disease. EMBO molecular medicine. 2013;5:1556–1568. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver G, Wehr R, Jenkins NA, et al. Homeobox genes and connective tissue patterning. Development. 1995;121:693–705. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsang TE, Shawlot W, Kinder SJ, et al. Lim1 activity is required for intermediate mesoderm differentiation in the mouse embryo. Developmental biology. 2000;223:77–90. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouchard M, Souabni A, Mandler M, et al. Nephric lineage specification by Pax2 and Pax8. Genes & development. 2002;16:2958–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia Y, Nivet E, Sancho-Martinez I, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent cells to ureteric bud kidney progenitor-like cells. Nature cell biology. 2013;15:1507–1515. doi: 10.1038/ncb2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikawa T, Poh AM, Kelly KA, et al. Induction and patterning of the primitive streak, an organizing center of gastrulation in the amniote. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2004;229:422–432. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Downs KM. The enigmatic primitive streak: prevailing notions and challenges concerning the body axis of mammals. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2009;31:892–902. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iimura T, Pourquie O. Collinear activation of Hoxb genes during gastrulation is linked to mesoderm cell ingression. Nature. 2006;442:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature04838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweetman D, Wagstaff L, Cooper O, et al. The migration of paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm cells emerging from the late primitive streak is controlled by different Wnt signals. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deschamps J, van Nes J. Developmental regulation of the Hox genes during axial morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:2931–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.01897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lengerke C, Schmitt S, Bowman TV, et al. BMP and Wnt specify hematopoietic fate by activation of the Cdx-Hox pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu P, Wakamiya M, Shea MJ, et al. Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation. Nature genetics. 1999;22:361–365. doi: 10.1038/11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson LT, Pembaur M, Potter SS. Hoxa11 and Hoxd11 regulate branching morphogenesis of the ureteric bud in the developing kidney. Development. 2001;128:2153–2161. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barak H, Huh SH, Chen S, et al. FGF9 and FGF20 maintain the stemness of nephron progenitors in mice and man. Developmental cell. 2012;22:1191–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Majumdar A, Vainio S, Kispert A, et al. Wnt11 and Ret/Gdnf pathways cooperate in regulating ureteric branching during metanephric kidney development. Development. 2003;130:3175–3185. doi: 10.1242/dev.00520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morizane R, Bonventre JV. Generation of nephron progenitor cells and kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature protocols. 2017;12:195–207. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freedman BS, Brooks CR, Lam AQ, et al. Modelling kidney disease with CRISPR-mutant kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent epiblast spheroids. Nature communications. 2015;6:8715. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morizane R, Lam AQ. Directed Differentiation of Pluripotent Stem Cells into Kidney. Biomarker insights. 2015;10:147–152. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S20055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanigawa S, Nishinakamura R. Expanding nephron progenitors in vitro: a step toward regenerative medicine in nephrology. Kidney international. 2016;90:925–927. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisenbrandt DL, Phemister RD. Radiation injury in the neonatal canine kidney. I. Pathogenesis. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1977;37:437–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown AC, Muthukrishnan SD, Oxburgh L. A synthetic niche for nephron progenitor cells. Developmental cell. 2015;34:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanigawa S, Sharma N, Hall MD, et al. Preferential Propagation of Competent SIX2+ Nephronic Progenitors by LIF/ROCKi Treatment of the Metanephric Mesenchyme. Stem cell reports. 2015;5:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanigawa S, Taguchi A, Sharma N, et al. Selective In Vitro Propagation of Nephron Progenitors Derived from Embryos and Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell reports. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Z, Araoka T, Wu J, et al. 3D Culture Supports Long-Term Expansion of Mouse and Human Nephrogenic Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:516–529. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toyohara T, Mae S, Sueta S, et al. Cell Therapy Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Renal Progenitors Ameliorates Acute Kidney Injury in Mice. Stem cells translational medicine. 2015;4:980–992. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012;380:756–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, et al. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371:58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xing L, Cui R, Peng L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells, not conditioned medium, contribute to kidney repair after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stem cell research & therapy. 2014;5:101. doi: 10.1186/scrt489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eirin A, Zhu XY, Krier JD, et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve revascularization outcomes to restore renal function in swine atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Stem cells. 2012;30:1030–1041. doi: 10.1002/stem.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliveira-Sales EB, Boim MA. Mesenchymal stem cells and chronic renal artery stenosis. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2016;310:F6–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00341.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duffield JS, Park KM, Hsiao LL, et al. Restoration of tubular epithelial cells during repair of the postischemic kidney occurs independently of bone marrow-derived stem cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:1743–1755. doi: 10.1172/JCI22593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Togel FE, Bonventre JV. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells protect against kidney injury. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:629–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saad A, Dietz AB, Herrmann SMS, et al. Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Increase Cortical Perfusion in Renovascular Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017020151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen C, Hou J. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy in kidney transplantation. Stem cell research & therapy. 2016;7:16. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0283-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bar S, Schachter M, Eldar-Geva T, et al. Large-Scale Analysis of Loss of Imprinting in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell reports. 2017;19:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merkle FT, Ghosh S, Kamitaki N, et al. Human pluripotent stem cells recurrently acquire and expand dominant negative P53 mutations. Nature. 2017;545:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature22312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dekel B. The Ever-Expanding Kidney Repair Shop. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2016;27:1579–1581. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takebe T, Enomura M, Yoshizawa E, et al. Vascularized and Complex Organ Buds from Diverse Tissues via Mesenchymal Cell-Driven Condensation. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharmin S, Taguchi A, Kaku Y, et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dekel B, Burakova T, Arditti FD, et al. Human and porcine early kidney precursors as a new source for transplantation. Nature medicine. 2003;9:53–60. doi: 10.1038/nm812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamaguchi T, Sato H, Kato-Itoh M, et al. Interspecies organogenesis generates autologous functional islets. Nature. 2017;542:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature21070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, Hamanaka S, et al. Generation of rat pancreas in mouse by interspecific blastocyst injection of pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;142:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Usui J, Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Generation of kidney from pluripotent stem cells via blastocyst complementation. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180:2417–2426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Caralt M, Uzarski JS, Iacob S, et al. Optimization and critical evaluation of decellularization strategies to develop renal extracellular matrix scaffolds as biological templates for organ engineering and transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2015;15:64–75. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song JJ, Guyette JP, Gilpin SE, et al. Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nature medicine. 2013;19:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nm.3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kolesky DB, Truby RL, Gladman AS, et al. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Advanced materials. 2014;26:3124–3130. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Homan KA, Kolesky DB, Skylar-Scott MA, et al. Bioprinting of 3D Convoluted Renal Proximal Tubules on Perfusable Chips. Scientific reports. 2016;6:34845. doi: 10.1038/srep34845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolesky DB, Homan KA, Skylar-Scott MA, et al. Three-dimensional bioprinting of thick vascularized tissues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:3179–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521342113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Musah S, Mammoto A, Ferrante TC, et al. Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip. 2017;1:0069. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]