Abstract

Purpose of Review

There are a limited number of studies investigating the association between the microbiome and HIV. Although the majority of these published investigations have focused on the role of the bacterial community (bacteriome) in this setting, a handful of studies have also characterized the role of the mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals. This review will summarize the most recent reports pertaining to the role of the fungal community in HIV.

Recent findings

Differences in the composition of the oral and respiratory mycobiome in HIV-infected individuals compared to uninfected individuals have been reported.

Summary

Our review shows that studies investigating the role of the mycobiome in the setting of HIV are severely lacking. With recent advances in our understanding of the composition of the human microbiome, investigations into the role of the bacteria and fungus comprising the overall microbiota and how the two interact to influence each other and the host is crucial.

Keywords: Mycobiome, HIV, Candida

Introduction

With the recent advances in next-generation sequencing, analysis and identification of the multitude of microrganisms comprising the human microbiome has become one of the most heavily studied areas in both health and disease. The majority of studies have focused primarily on the bacterial community of the microbiome, known as the bacteriome. Bacteria have long been proven to be a major source of infection, as well as initiators in the perpetuation of several different autoimmune disorders. However, the fungal portion of the microbiome (mycobiome) has long been excluded from this analysis, despite the fact that fungi are known to be associated with particular diseases (Candida in oral disease and Cryptococcus in cryptococcal meningitis). Moreover, before the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART), Candida was globally an HIV-defining illness. Fortunately, a number of studies have recently been published describing the diversity and alterations of the microbiome in the setting of HIV. The following is a summary of their findings.

The Oral Mycobiome in HIV

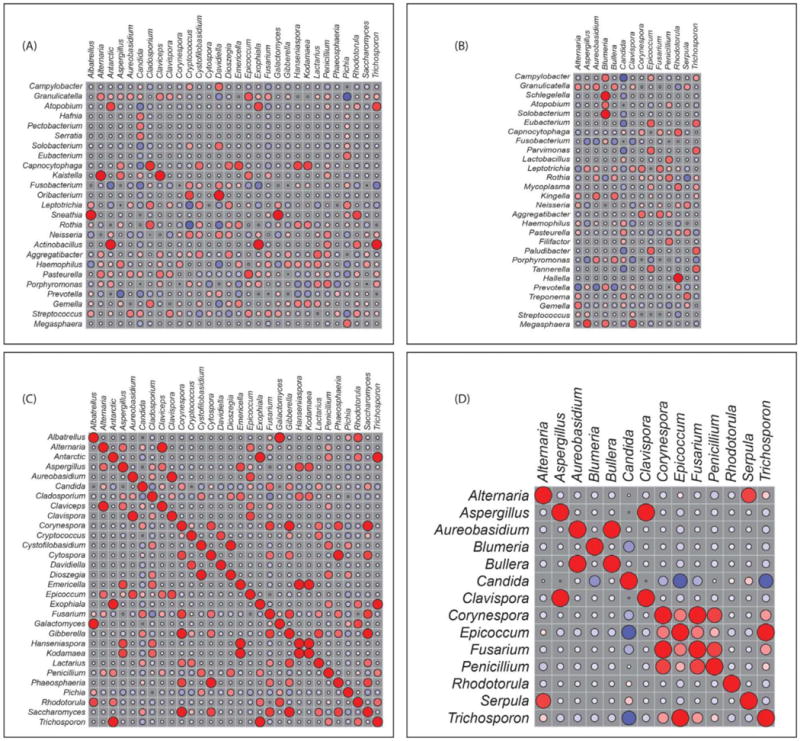

The first study to characterize the role of the mycobiome and bacteriome in HIV-infected patients was published by our group [1]. We used next generation sequencing approach and analyzed oral rinse samples from a total of 24 subjects, 12 HIV-infected and 12 uninfected. Our data showed that the oral bacteriome of HIV-infected individuals was similar to that of uninfected participants with very few differences between the two profiles. Conversely, the oral mycobiome of HIV-infected individuals was different compared to uninfected subjects. More specifically, the most common genera in HIV-infected individuals were Candida, Epicoccum, and Alternaria (present in 92%, 33%, and 25%, respectively), while the most abundant genera present in uninfected participants were Candida, Pichia, and Fusarium (58%, 33%, and 33%, respectively). The core oral mycobiome (COM) of HIV-infected and uninfected individuals consisted of five fungal genera; of these, Candida and Penicillium were common between the two groups. These findings demonstrate that the COM of HIV-infected individuals differs from that of age- and sex-matched uninfected controls. This study clearly shows that HIV impacts the fungal community and should be taken into consideration in studies investigating the impact of the microbiota in HIV. Additionally, the correlation between bacteria and fungi was conducted to determine the inter-kingdom interactions (See Figure 1). This analysis showed significant correlation between 15 bacterial-fungal pairs in noninfected study participants. Among them, two pairs (Rothia-Cladosporium and Granulicatella-Cryptococcus) were negatively correlated, while the remaining 13 pairs exhibited positive correlation. In comparison, there were 12 significant bacterial-fungal pairs in HIV-infected patients, with 11 positive and one negative correlations.

Fig 1.

Correlation of bacteriome and mycobiome: bacterial-fungal interactions in (A) uninfected and (B) HIV-infected study participants. Fungal-fungal interactions among different fungi in (C) uninfected and (D) HIV-infected study participants. Red: Positive correlation; Blue: negative correlation; diameter of circles represents the absolute value of correlation for each pair of the microbe-microbe matrix. Reproduced from [1]

The Respiratory Tract Mycobiome in HIV

A study published by Cui et al. [2] characterized the profile of the fungal community residing in the respiratory tract of HIV-infected individuals compared to uninfected controls. These researchers analyzed the microbiota in oral wash, induced sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage samples collected from 56 subjects (32 HIV-infected and 24 uninfected). Principle component analysis (PCA) showed that fungi present in bronchoalveolar lavage samples clustered together with those in oral wash samples. Interestingly, induced sputum samples clustered partially with oral wash samples, but not with bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. These clustering patterns indicate that there are shared and unique taxa present at different levels of the respiratory tract. Moreover, the overlap of fungal communities in oral wash and bronchoalveolar lavage samples suggests that some microbes present in the lungs may originate from the mouth, most likely from microaspiration of organisms from the mouth into the lungs. In the same study, these authors showed that the genus Candida, which comprised more than 90% of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) reads, was dominant in oral wash compared to bronchoalveolar lavage samples, suggesting that Candida is the most common species in the mouth, while Saccharomyces was overrepresented in the lung. This data is in agreement with our earlier findings described above [1].

Importantly, Cui et al. showed that there is significant alteration in the fungal community of the lung between HIV-infected individuals with low CD4 counts and uninfected subjects. In this regard, 9 fungal species were overrepresented in the bronchoalveolar lavage of HIV-infected individuals compared to uninfected subjects (Pneumocystis jirovecii, Junghuhnia nitida, Phlebia tremellosa, Oxyporus latemarginatus, Sebacina incrustans, Ceriporia lacerata, Pezizella discrete, Trametes hirsute, and Daedaleopsis confragosa). Two of these species (Pneumocystis jirovecii and Ceriporia lacerata) are known lung pathogens that are associated with immunosuppression. Additionally, P. jirovecii is a leading cause of pneumonia in HIV-infected and other immunocompromised individuals.

The Gastrointestinal Mycobiome in HIV

Perhaps the most influential portion of the mycobiome and microbiome in general lies in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In recent years, several studies have analyzed the mycobiome comprising the GI tract, in both health and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, very few studies have sought out a link between the mycobiome of the GI tract and its role in HIV. Instead, studies have mainly focused on the bacterial population, excluding the fungal species. A review by Gouba et al. [3] provided an overview of fungal species in the human digestive tract and the differences between healthy individuals and patients with diseases, including HIV. In their analysis, they showed that Candida spp. were significantly more prevalent in the intestinal mycobiota of HIV-infected patients compared to healthy controls, findings similar to that reported in the oral cavity of HIV-infected individuals. Their review showed that there is a decrease in fungal species diversity in HIV-infected patients. Moreover, Candida spp. were significantly more prevalent in HIV-infected patients in cases of diarrhea and a recent antibiotic treatment, compared to healthy controls. The observation that similar mycobiome profiles are seen in the oral cavity and the gut is not surprising. However, studies that compare the oral and GI microbiota in the same individuals along the line of the study of Cui et al. will provide insight into whether the gut microbiome is seeded through the mouth.

Conclusion

Our review clearly shows that there is a dearth of information on the association of the mycobiome with HIV infection. Thus, it is highly critical that more studies are conducted in this area. Moreover, recent discoveries have shown that bacteria and fungi cooperate in a strategic evolutionary manner to effect disease states including Crohn’s disease and diabetic wound infection [4]. In this regard, potential studies regarding the role of the mycobiome in HIV could be modeled upon our recent findings in Crohn’s patients. We identified a positive correlation between bacteria and fungi, wherein Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, and the fungus Candida tropicalis were elevated in the GI tract of patients with CD compared to their non-Crohn’s healthy relatives. Subsequently, we studied these three organisms in vitro to determine interactions among them. Interestingly, we found that they cooperate in such a way as to form large, robust biofilms capable of activating the host immune response. Thus, once the mycobiome and the bacteriome are identified in HIV-infected patients, bacterial-bacterial, fungal-fungal, and fungal-bacterial, as well as microbial-host interactions should be undertaken. Such studies will open the way to mechanistic investigations. It is critical that future studies investigate the polymicrobial interactions in the HIV setting. Focusing on the bacterial or fungal community alone is myopic.

Another area that has been understudied is the role of the mycobiome in leaky gut syndrome. Only one study is available that looked at anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) in HIV-infected patients [5]. This study showed that ASCA serological markers may provide a non-invasive approach to monitor HIV-related inflammatory gut disease. Further studies to investigate their clinical significance in HIV-infected individuals are warranted. Additionally, longitudinal studies are needed to identify specific host-microbe/microbe-microbe interactions that modulate immune status in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Such studies could lead to the development of targeted immune-based therapies. With the completion of the phase I of the human microbiome project (HMP), studies aimed at harnessing the plethora of generated information should be encouraged. Particularly, investigations into novel approaches (i.e. diet, probiotics, and therapeutics) to manipulate the microbiota, both bacteria and fungi, to restore the microbial balance in the GI tract is crucial. For example, to address the imbalance in the microbiota, it may be possible to use antifungals together with probiotics. Antifungals will control the overgrowth of fungi, while probiotics can help restore and maintain the balance of the microbiota. Finally, there is a need to conduct studies in HIV-infected patients that use a comprehensive systems biology approach so as to identify the link between the mycobiome, bacteriome, virome, and their metabolites. This all encompassing approach should be encouraged.

Key Points.

Limited studies have been done to gain insight into the role of the mycobiome in HIV.

Researchers should be encouraged to investigate the inter-kingdom interaction (mycobiome and bacteriome) and how these interactions influence GI disease in HIV.

Identifying fungal biomarkers may provide non-invasive approaches for gut health in HIV.

Concerted efforts should be directed to the development of dietary/probiotic and therapeutics aimed at manipulating the gut microbiota to maintain microbial balance.

Systems biology approach that link the microbiota, their metabolites, and host immunity is badly needed

Studies into whether the microbiota plays a role in Immune failure patients (CD4 T cells <350/μL and immune success patients (CD4 T cells >500/μL) in spite of antiretroviral therapy is warranted.

Acknowledgments

None

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding support is acknowledged from the National Institutes of Health Grants number: R01DE024228 and U01 AI105937-01.

Financial support and sponsorship

None

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- 1*.Mukherjee PK, Chandra J, Retuerto M, et al. Oral Mycobiome Analysis of HIV-Infected Patients: Identification of Pichia as an Antagonist of Opportunistic Fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(3):e1003996. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003996. This is the first study to identify the oral mycobiome in HIV-infected patients. This article highlights the important role that the mycobiome plays in the setting of HIV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2**.Cui L, Lucht L, Tipton L, et al. Topographic Diversity of the Respiratory Tract Mycobiome and Alteration in HIV and Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:932–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1583OC. This study is one of the first to characterize the respiratory tract mycobiome and link the changes in fungal communities seen in HIV-infected patients with lung disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gouba N, Drancourt M. Digestive tract mycobiota: A source of Infection. Médecine et maladies infectieuses. 2015;45:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4*.Ghannoum M. Cooperative Evolutionary Strategy between the Bacteriome and Mycobiome. mBio. 2016;7(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01951-16. mBio.01951-16. This commentary provides great insight into the strategic cooperation between the bacteriome and mycobiome, and its influence on disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamat A, Ancuta P, Blumberg RS, Gabuzda D. Serological Markers for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in AIDS Patients with Evidence of Microbial Translocation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]