Abstract

We analyzed China’s current use of and microbial resistance to antibiotics, and possible means of reducing antimicrobial resistance. Interventions like executive orders within clinical settings and educational approach with vertical approaches rather than an integrated strategy to curb the use of antimicrobials remain limited. An underlying problem is the system of incentives that has resulted in the intensification of inappropriate use by health professionals and patients. There is an urgent need to explore the relationship between financial and non-financial incentives for providers and patients, to eliminate inappropriate incentives. China’s national health reforms have created an opportunity to contain inappropriate use of antibiotics through more comprehensive and integrated strategies. Containment of microbial resistance may be achieved by strengthening surveillance at national, regional and hospital levels; eliminating detrimental incentives within the health system; and changing prescribing behaviors to a wider health systems approach, to achieve long-term, equitable and sustainable results and coordinate stakeholders’ actions through transparent sharing of information.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, containment, appropriate use

Introduction

On April 30, 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) released its first surveillance report on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in 114 countries.1 According to the report, resistance to a wide range of anti-infective agents is a worldwide public health threat that continues to grow, and its prevalence is closely related to the overuse of antibiotics. This is of particular concern in the developing world, where bacterial infection remains one of the major precursors of disease. There, antimicrobial agents play a critical role in healthcare; thus, the increasing rates of AMR pose a serious threat to infection control. Overprescription of antimicrobials not only wastes limited health resources but also creates substantial financial burdens and poor health outcomes for both individuals and countries. Because China’s population accounts for one-fifth of the world’s population, its efforts and contributions to controlling AMR are critical to overall global health.

Antimicrobial resistance in China

From 1999 and 2001, the mean prevalence of microbial resistance among hospital-acquired infections in China reached 41% (range, 23%–77%), and community-acquired infections rose to 26% (range, 15%–39%).2 This, coupled with China’s high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), has created a major healthcare problem. In fact, from 2006 to 2010, the isolation rate of MRSA in clinical settings was between 55% and 63%, with resistance rates at tertiary hospitals in large cities higher than those in lower-level hospitals. The CHINET AMR surveillance network reported that in these tertiary hospitals, the average MRSA isolation rate ranged from 29.1% to 74.2% in 2014, with an average of 44.6%. There are also significant geographical differences reported across China. For example, eastern China has the highest prevalence of MRSA at 76.9%, and the prevalence in large cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou are higher than those of smaller cities.3–4 It has been reported that 32.7% of S. aureus isolated from pediatric patients is MRSA, which is about half that seen in adult patients.5

Moreover, MRSA’s antimicrobial resistance spectrum is broad, with resistance rates of up to 50% for macrolides, clindamycin, aminoglycosides and quinolones.6,7 Among gram-negative bacteria, resistance rates of non-fermentative bacteria were the lowest. The resistance rates of Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter and Stenotrophornonas to cefoperazone/sulbactam were 28.86%, 18.53% and 20.85%, respectively. Resistance rates of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter to imipenem were 33.81% and 22.86%.8 Since the initial reports of the 1990s, and particularly since 2000, extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae have spread rapidly across China. The prevalence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli strains varies across regions. Even carbapenems, once regarded the treatment of last resort against serious gram-negative bacterial infections, have begun to lose efficacy as carbapenem-resistant bacteria emerge and quickly spread.

The resistance rates of nosocomial infections are on the rise, and most are multidrug resistant. Antimicrobial agents with enzyme inhibitors are more sensitive than non-enzyme inhibitors. Resistance has a tendency to increase, especially in Acinetobacter baumannii and to third-generation cephalosporins (Table 1).

Table 1.

National resistance rates of common bacterial pathogens.

| Bacterial pathogen | Antimicrobials | Resistance rate (%) | No. tested isolates | Type of surveillance, population, or sampling | Year data collected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | fluoroquinolones | levofloxacin | 53.2 | 129,240 | Comprehensive | 2012 |

| ciprofloxacin | 56.9 | 135, 736 | ||||

| 3rd-generation cephalosporins | ceftazidime | 31.3 | 146,497 | |||

| ceftriaxone | 65.6 | 113,892 | ||||

| cefotaxime | 70 | 79,906 | ||||

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 3rd-generation cephalosporins | ceftazidime | 25.1 | 102,420 | 2012 | |

| ceftriaxone | 44.4 | 81,541 | ||||

| efotaxime | 52.5 | 55,433 | ||||

| carbapenems | meropenem | 7.1 | 54 6,100 | |||

| imipenem | 7.7 | 80,571 | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | methicillin | oxacillin | 37.1 | 57,294 | 2012 | |

| cefoxitin | 41.1 | 25,636 | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumonia | penicillin | 1.9 | 420 | Targeted | 2010 | |

| non-Typhi Salmonella (NTS) | fluoroquinolones | 11.9 | 177 | 2011 | ||

| Shigella | fluoroquinolones | ciprofloxacin | 27.9 | 308 | Comprehensive | 2011 |

| levofloxacin | 9.7 | |||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 3rd-generation cephalosporins | 21 (mainland) 1.6 (HKSAR) | 1349 (mainland) 1225 (HKSAR) | Reported to Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme | 2011 | |

Source: World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance. 2014. Geneva: WHO.

Overall resistance rates have remained stable since 2011 when the Chinese government initiated nationwide interventions to reduce the overuse of antimicrobials. However, resistance to carbapenems continues to increase rapidly.

Antimicrobial use in China

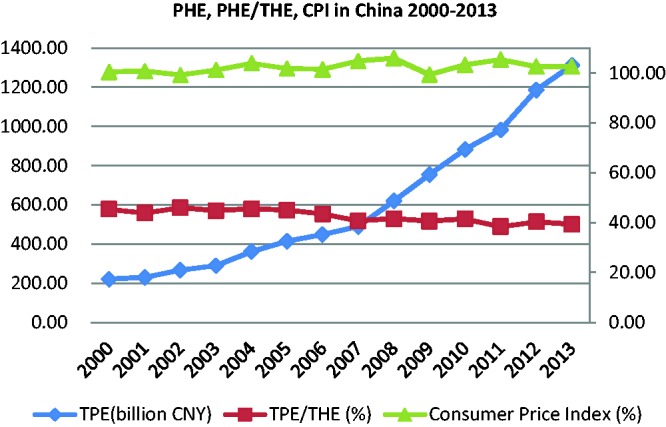

The increasing prevalence of AMR is closely related to the overuse of antimicrobial agents. As Figure 1 shows, since the early 2000s, total pharmaceutical expenditure (TPE) in China has been between 40% and 50% of the national total health expenditure (THE).9,10 During the period 2000–2013, the TPE surged even though the consumer price index remained stable. In 2006, TPE reached 43.5%, much higher than the median in low-income countries (29.5%) and twice the global median (23.1%). Thirty to fifty percent of the medicines consumed in hospitals are antimicrobial agents, and around 70% of inpatients are treated with antimicrobials. China’s consumption of antimicrobials and antimicrobial infusions per capita is far higher than that of high income countries (HICs), and the level of inappropriate use of medicines is even higher than that of some low-income countries.11 The situation in primary care is even more challenging. In 2008, 57% of prescriptions from primary care facilities included antimicrobials, and 39% included antimicrobial infusions; the average number of medicines per prescription was 3.1.12 These numbers exceed the global medians obtained by the 1990–2009 WHO survey of primary care facilities worldwide. The survey looked at high-, upper and lower middle-, and low-income countries to determine the median proportions of prescriptions for antimicrobials and infusions, as well as the average number of medicines per prescription. The medians of prescriptions for antimicrobials in these countries were 38.2%, 42.8% and 48.7%, respectively. For infusions and average number of medicines per prescription, these proportions were 11%, 15% and 23.2% and 2.3, 2.6 and 2.5, respectively.13 By comparison, China’s pharmaceutical expenditures are exorbitant, and patients bear much of the financial burden. For example, the 2011 THE per capita in China represents USD 265 of purchasing power parity, less than both the global median (USD 442) and the global average (USD 899). This figure is only one-third of the average in upper-middle-income countries (USD 830) and 6% of the average in HICs (USD 4,246).14 Despite these financial disparities, annual antibiotic consumption per person in China was about 138 g, which is 10 times that of the United States.15 In 2006, China produced an estimated 210,000 tons of antibiotics, of which only 30,000 tons were exported; the remaining 180,000 tons were consumed domestically. Many studies have also demonstrated that Chinese hospitals prescribe antibiotics at extremely high rates and that those most commonly used for inpatient care are broad-spectrum antibiotics.5,16–19

Figure 1.

TPE, TPE/THE and CPI in China, 2000–2013.

Abbreviations: TPE, total pharmaceutical expenditure; THE, total health expenditure; CPI, consumer price index.

Antibiotics have been less frequently prescribed in Chinese hospitals since 2008 owing to continued government efforts to strengthen their regulation, especially the 2011 nationwide initiative to reduce antibiotics use. The level of total consumption of antibiotics, measured as defined daily dose (DDD), among inpatients has dropped from a maximum of 910 DDD/1,000 patient days in 2008 to 473 DDD/1,000 patient days in 2012. However, 50% of hospitalized patients were still given antibiotics in 2012, the majority of whom received broad-spectrum antibiotics. However, the proportion of penicillins (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System code J01C), which has continuously decreased since 2008, was only 11%.20

As mentioned above, the inappropriate use of medicines wastes limited health resources. This not only places a huge financial burden on the government, society and individuals but also carries certain health risks.15 In 2005, a study entitled Public Security Concerns of Irrational Use of Antibiotics looked at several possible outcomes resulting from the aforementioned waste. The study estimated that the costs for additional hospital medicines were CNY 21.8 billion (USD 2.7 billion, exchange rate = 8.1) and those for additional hospitalizations were CNY 42.0 billion (USD 5.2 billion). Further, the additional pharmaceutical and hospitalization costs resulting from drug resistance were CNY 3.7 billion (USD 0.5 billion) and 1.3 billion (USD 0.2 billion), respectively. In that study, after adjusting for multiple factors, the hospitalization costs for patients with resistant infections were 1.5 times those of patients with antibiotic-sensitive (non-resistant) infections. Based on the actual mortality rate for patients with resistant bacterial infections (11.7%) and the average mortality rate for those with general infections (5.4%), the additional deaths attributable to AMR cost approximately CNY 489,000 per year for the country as a whole. In addition, the loss in productivity is estimated at CNY 4.7 billion (USD 0.6 billion) and the annual medical costs associated with drug reactions owing to AMR are estimated at CNY 1.9–9.1 billion (USD 0.2–1.1 billion). These costs would tax the healthcare budgets of even the wealthiest countries,

Current policies to improve antibiotics prescription and reduce antimicrobial resistance

In China, two main government agencies regulate the use of antibiotics: the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) is responsible for registering, producing and distributing medicines; and the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) oversees their clinical use, in addition to pharmacies and infection control in health facilities. To encourage the appropriate use of medicines, these agencies have implemented a series of regulations and strategies, which include requesting retail pharmacies to sell antimicrobials with prescriptions in 200321 and developing clinical pathways, standard treatment guidelines and clinical use guidelines for antibiotics and other medicines in 2004.22 National antimicrobial clinical use and resistance surveillance networks were created in 2005 to collect, analyze and report routine data from hospitals.23 Prescriptions were formally regulated in 2007,24 and pharmacy administration in health facilities was further strengthened in 2011.25 A national medicines use surveillance network (for general medicines, not specifically for antimicrobials) was set up in 2009 to collect medicines use data from health facilities and to recommend interventions for improving the use of medicines.26 In 2012, antimicrobials stocked and used in different types of health facilities were clearly delineated, and national targets for the clinical use of antimicrobials were set.27 The National Action Plan to Contain Antimicrobial Resistance (2016–2020) was published in 2016.28

Despite the implementation of numerous policies, nationwide use of surveillance networks and a national oversight committee, the inappropriate use of medicines continues in China. According to the National Surveillance Report of Adverse Drug Reactions in 2015, allopathic (Western) medicines accounted for 81.2% of the total adverse drug reaction reports, among which 44.9% were anti-infectives and 61.3% were antimicrobial infusions.29 These reports indicate that a serious problem persists. In 2012, the proportion of total pharmaceutical expenditure remained unacceptably high at 40% of THE,10 and the average proportion of costs for outpatient and inpatient medicines remained at respectively 50% and 40% of average hospital expenditures per patient.30 It is clear that more must be done to ameliorate this situation.

The main reason for the lack of success in this regard is that intervention strategies have remained limited to executive orders and one-time inspections, within the scope of clinical educational interventions. The pharmaceutical sector is complex and involves many stakeholders and divergent interests. Policy interventions to improve medicines use by any one actor will impact the behavior of the rest. Because of the special nature of this sector, case-by-case solutions that only target an individual problem often fail to achieve the expected results because the goals of individual policies may be inconsistent with or even diametrically opposed to other policies. Moreover, the interests of different entities often interfere with those of other bodies. An example is the national health system’s incentive structure, which adversely influences health professionals and intensifies the problem. Adding to these obstacles are the lack of suitable, integrated strategies, lack of interaction between clinical and social science professionals and lack of acknowledgment of prescriber and patient behaviors. Until all these obstacles are overcome, the inappropriate use of medicines can never be effectively and sustainably controlled. A wider, systemic approach is needed to achieve long-term, equitable and sustainable results. Further research that explores the relationship between appropriate incentives (including financial and non-financial approaches) and the behaviors of providers and patients are needed to effect lasting change.

Challenges to reducing antimicrobial resistance

According to one study of global antibiotic consumption,31 worldwide use between 2000 and 2010 rose a staggering 36%, from 54,083,964,813 to 73,620,748,816 standard units. BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), with 41% of the world’s population in 2010,32 are responsible for more than three-quarters of that surge. China was the second largest consumer of antibiotics in the world in 2010, accounting for 57% of the increase in the hospital sector of BRICS countries. One reason for this is the rapid economic growth that has enabled China to achieve universal health coverage in 2012.33 While this situation has secured much greater access to medicines (including antibiotics), it has also meant that many broad-spectrum antibiotics have been sold over-the-counter without a documented clinical need. Official regulations addressing this have in fact been issued; however, they have not been rigorously implemented in some areas of the country. Moreover, official guidelines for the clinical use of antimicrobials in China have only recently been developed, and evidence-based use has not yet been widely accepted by health professionals, who generally adopt the opinions of their senior colleagues.34

Compared with hospital care in urban areas, primary care in rural areas faces even greater challenges because of the lack of qualified health professionals and poor access to information, as well as lower economic development. Problems of irrational use of antibiotics at primary care facilities in rural areas may lead to an increasing number of resistance problems at higher levels of care. In addition, the increase in travel and migration that has accompanied China’s rapid economic development has also contributed to the growth of the nation’s AMR problem.

Most importantly, the Chinese health system has been burdened by detrimental financial incentives, which have intensified the overuse of antimicrobial drugs. These incentives include 1) inappropriate government subsidies whereby limited resources are focused on tertiary hospitals and infrastructure construction, and most other public health facilities depend on the sale of medicines to generate funding,35 and 2) distorted pricing policies whereby the government sets the prices for medical services far below the real cost whereas prices for large-scale medical equipment, diagnostic tests, medical supplies and brand name medicines are set much higher than the actual cost, which induces health providers to overprescribe expensive medicines and diagnostic tests rather than provide quality care that is cost-effective.36 Other major problems include the conflict between insufficient public resources and the resource-exhausted fee-for-service provider payment mechanism,37 unsound medicine procurement mechanisms with no appropriate incentives for facilities to procure low-priced medicines, and “reverse-proof” responsibility for medical disputes that encourages a defensive, prescription-oriented attitude among physicians.38

A fourfold path to future reduction of AMR in China

Strengthening surveillance at all levels

National level

In response to World Health Assembly resolutions urging member states to formulate measures to promote the proper and cost-effective use of antibiotics,39 China’s NHFPC—formerly known as the Ministry of Health (MoH)—committed to increasing its scrutiny of antimicrobial use and resistance. Two national surveillance networks were established in 2005 by the MoH for the above purpose. Initially, 35 tertiary hospitals joined the networks, and this had expanded to 1,427 hospitals (including both tertiary and secondary hospitals) by the end of 2014. These networks regularly collect, consolidate, summarize and analyze data on clinical antimicrobial use and resistance. They have also established national databases for routine surveillance and evaluation, provided feedback to member hospitals and have periodically reported to the MoH. The networks also developed a set of standardized indicators and methods for data collection as well as an electronic data reporting system that enables hospitals to report online. These networks also disseminate standardized data collection and reporting methods at the local level and act as a clearinghouse to share information across all levels of surveillance and evaluation.

Regional level

Until the end of 2014, each province had its own surveillance network. Some regions had also set up intercity networks, which greatly strengthened surveillance and evaluation and informed policy at the local level.

Hospital level

According to the national campaign,23 all tertiary and secondary hospitals are required to monitor and evaluate antimicrobial clinical use and resistance at their facility. The NHFPC also created a set of national targets for all participating hospitals, intended to decrease the number of prescriptions that included antibiotics to < 20% and < 60% for outpatients and inpatients, respectively. Prophylactic antibiotics are to be given before surgical incision (except cesarean), and the general duration of prophylaxis is to be < 24 hours (except under specific conditions). Hospitals are required to maintain total inpatient consumption of antibiotics for systemic use (ATC code J01) at < 400 DDD/1,000 inpatient days. At each of the hospitals involved, training is provided to help staff clearly understand the new program’s requirements and goals, as well as to learn strategies for achieving the targets.

Elimination of inappropriate financial incentives

Ongoing health system reforms in China have created an opportunity to address the issue of incentives within the healthcare system. The problem stems from an illogical financing model in which hospital revenue is generated by mark-up of medicines. As top decision makers work to improve the system, this model is giving way to a financing model in which revenue is instead generated by providing quality services through allowing market competition. The distorted pricing system of medical services and medicinal products has been changing towards a value-based pricing and price negotiation mechanism, to replace the former cost plus price setting methods. Health insurance programs are required to develop innovative strategies to create incentives for the appropriate use of medicines. These measures include expanding coverage for both inpatient and outpatient services; increasing diagnostic, treatment and dispensing fees to make up for lost revenues from medicines sales; changing payment methods from retrospective fee-for-service to prospective capitation-based and case-based mixed payments; and supporting polices to secure the quality of care, including the appropriate use of medicines.

Prescription behavior changes

Prescription behavior is determined by a variety of internal, external, social, economic and cultural factors. The effectiveness of interventions to improve prescribing behavior depends to a large degree on the content, delivery mechanism, intensity, context and implementation environment. Medicine interventions can be categorized by type of measure, including clinical, educational, managerial, financial and regulatory.40,41 Effective interventions are always broad-based, multidimensional programs that are adapted to the particular situation and address local barriers to change. No single intervention can modify all behaviors in any given setting.42–45 Thus, simply restricting the use of antibiotics does not lead to a desirable, scientifically sound and cost-effective outcome. One reason is that medical professionals have a seemingly deep-rooted dislike of inexpensive, basic antibiotics such as penicillins and other narrow spectrum antibiotics.20 Therefore, clinical educational interventions, even those linked to managerial measures, have failed to counteract these negative perceptions. Rather than simply restricting use, more sophisticated and comprehensive policies are needed, especially when hospital financing is heavily dependent on the sale of medicines and prescribers themselves can earn additional income from dispensing or selling medicines.

The ways in which healthcare is financed and how healthcare providers are paid greatly affect treatment decisions because financing mechanisms create different incentives for providers.46 In many resource-poor low- and middle-income countries, for instance, health systems are not appropriately funded and regulated.47 Consequently, economic factors can be important barriers to guideline compliance.48 New and more sophisticated financing mechanisms are needed, with units of payment becoming broader and prices for bundled services set on a prospective basis.49,50

Coordination of stakeholders and information sharing

Coordination and information sharing could provide an up-to-date overview of the present situation of AMR. Increased collaboration between networks will make it increasingly important to share experiences and form a basis of coordinated collaboration to change behaviors. In addition, surveillance systems must be flexible and able to adapt to emerging microbial resistance and not focus on what is already known. Surveillance systems should also be able to promptly deliver information to avoid delays in public health actions at both local and national levels.

Conclusion

The use of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance is a great challenge for China. Fortunately, ongoing health system reforms have created opportunities to address this challenge using more comprehensive and integrated strategies so as to fundamentally change the incentives for use of antibiotics and to contain resistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those who provided assistance with the data collection and editing of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.The World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 2.Zhang R, Eggleston K, Rotimi V, et al. Antibiotic resistance as a global threat: evidence from China, Kuwait and the United States. Global Health 2006; 2: 6–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun HL, Wang H, Chen MJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistant surveillance of gram-positve cocci isolated from 12 teaching hospitals in China in 2009. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2010; 49: 735–740. [in Chinese, English Abstract]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu X, Zhang P, Fan X, et al. Mohnarin 2008 report: results of Staphylococcus and enterococcus resistance. Chin J Antibiot 2010; 35: 536–543. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZKSS201007013.htm (accessed 16 January 2017). [in Chinese, English Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu W, Chen L, Li H, et al. Novel CTX-M {beta}-lactamase genotype distribution and spread into multiple species of Enterobacteriaceae in Changsha, Southern China. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 63: 895–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CHINET Annual Report 2014. http://www.clinphar.cn/thread-325066-1-1.html (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 7.Xiao Y, Giske CG, Wei ZQ, et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of antimicrobial resistance in China. Drug Resist Updat 2011; 14: 236–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen X, Ren N, Wu A, et al. Antimicrobiai resistance of bacteria and changing trend in China Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System. Chin Infect Control 2009; 8: 389–396,408. [Google Scholar]

- 9.China National Health Development Research Center. China national health accounts report. Beijing, CNHDRC; 2015.

- 10.National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical yearbook, Beijing: China Statistics Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The World Health Organization. The world medicines situation 2011-expenditures, Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Health Statistics and Information, MoH, P.R.China. Research on health service of primary health care facilities in China, Beijing: China Medical Union University Publishing House, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway KA et al. Progress in Standard Indicators of Medicines Use Over 20 Years. Abstract 337 of the 3rd International Conference of International Use of Medicines. 2011. http://www.inrud.org/ICIUM/ConferenceMaterials/default_015.html (accessed 8 November 2015).

- 14.The World Health Organization. World health statistics 2011, Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, et al. Report of public security concerns of irrational use of antibiotics, Beijing: Chinese Science and Technology Association, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang J, et al. Minutes of the national seminar on promoting rational use of medicines. National Medical Journal of China 1985; 65: 258–263. http://zhyxzz.yiigle.com/CN112137198505/850875.htm (accessed 16 January 2017). [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YH, Fu SG, Peng H, et al. Abuse of antibiotics in China and its potential interference in determining the etiology of pediatric bacterial diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993; 12: 986–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Health Statistics and Information, MoH, P.R.China. Research on Health Service of Primary Health Care Facilities in China, Beijing: China Medical Union University Publishing House, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO-China 2008-9 project report on improving prophylaxis antibiotics for clean surgery. WP/2008/CHN, PE: 04.07.

- 20.Sun J, Shen X, Li M, et al. Changes of patterns in antibiotic use in Chinese public hospitals (2005–2012) and a benchmark comparison with Sweden in 2012. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2015; 3: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.State Food and Drug Administration, P.R.China. The announcement of strengthening the supervision of antimicrobials distribution in the retail pharmacies. Document No. 289 of 2003. http://www.sfda.gov.cn/WS01/CL0844/10126.html (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 22.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Clinical guidelines for antimicrobials clinical use. Document 285 of 2004.

- 23.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Announcement of setting up the monitoring network for antimicrobials clinical use and resistance. 2005. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/zhuzhan/zcjd/201304/b0da0ebfc7b3428f98d435a29cfa4250.shtml (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 24.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Prescription Administration. Document No. 53 of 2006. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/mohyzs/s3572/200804/29279.shtml (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 25.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Pharmacy administration in health facilities. Document No. 11 of 2011. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3593/201103/4119b5de252d45ac916d420e0d30fda7.shtml (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 26.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Announcement of strengthening monitoring of medicines use. Document No. 13 of 2009. http://govinfo.nlc.gov.cn/gtfz/zfgb/wsb/20095070/201010/t20101011_446876.html# (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 27.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. Regulation on antimicrobials clinical use. Ministerial Order No. 84 of 2012. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/zhuzhan/wsbmgzl/201205/347e8d20a6d442ddab626312378311b4.shtml (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 28.National Health and Family Planning Commission. National Action Plan to Contain Antimicrobial Resistance (2016–2020). http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3593/201608/f1ed26a0c8774e1c8fc89dd481ec84d7.shtml (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 29.China Food and Drug Administration. ADR monitoring annual report 2015.http://www.sda.gov.cn/WS01/CL0051/60952.html (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 30.Ministry of Health, P.R.China. China Health Statistics Yearbook 2013. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2013/index2013.html (accessed 1 July 2016).

- 31.Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository. World health statistics, WHO: Geneva, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Health system reform office of the State Council. Three year summary report of deepening the health system reform. Unpublished report, Beijing: National Development and Reform Commission, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun J. Systematic review of interventions on antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery in Chinese hospitals during 2000–2012. J Evid Based Med 2013; 6: 126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The World Bank. Fixing the Public Hospital System in China. China Health Policy Notes No.2, Washington DC: The World Bank, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The World Health Organization. Pharmaceutical Policy in China: Issues and Problems Report prepared for the Chinese government for the national health system reform. WHO Archives. http://archives.who.int/tbs/ChinesePharmaceuticalPolicy/English_Background_Documents/summarypapers/PPChinaIssuesProblemsShenglan.doc (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 37.Yip WC, Hsiao W, Meng Q, et al. Realignment of incentives for health-care providers in China. Lancet 2010; 375: 1120–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun J. International updates for improving use of medicines. China Pharmacy 2012; 23: 1249–1252. http://mall.cnki.net/magazine/Article/ZGYA201214003.htm (accessed 16 January 2017). [in Chinese, English Abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Assembly Resolutions 51.17. Emerging and other communicable diseases: antimicrobial resistance. 1998; 58.27, Improving the containment of antimicrobial resistance. 2005; 60.16, Progress in the rational use of medicines, including better medicines for children. Geneva: WHO, 2007.

- 40.Holloway KA. Combating in-appropriate use of medicines. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011; 4: 335–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.le Grand A, Hogerzeil HV, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Intervention research in rational use of drugs: a review. Health Policy Plann 1999; 14: 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005, pp. CD003539–CD003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sketris IS, Langille Ingram EM, Lummis HL. Strategic opportunities for effective optimal prescribing and medication management. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 16: e103–e125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, pp. CD005470–CD005470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. WHO Medicines Use in Primary Care in Developing and Transitional Countries. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s16073e/s16073e.pdf (accessed 21 November 2016).

- 46.Yip W, Hsiao W. Harnessing the privatization of China’s fragmented health-care delivery. Lancet 2014; 384: 805–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mills A. Health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. WHO policy perspectives on medicines — promoting rational use of medicines: core components, Geneva: WHO, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno-Serra R. The impact of cost-containment policies on health expenditure: Evidence from recent OECD experiences. OECD Journal on Budgeting 2014; 13: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dusheiko M, Gravelle H, Jacobs R, et al. The effect of financial incentives on gatekeeping doctors. evidence from a natural experiment. J Health Econ 2006; 25: 449–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]