Short abstract

Objective

To evaluate the radiosensitivity effect of CpG oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ODN) 7909 on human epidermoid cancer strain-2 (Hep-2) cells in vitro and discuss the potential for improved radiotherapy treatment in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 expression was assessed in Hep-2 cells using Western blots and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Cell Counting Kit-8 was used to detect Hep-2 cell viability at 24 and 48 h following treatment with different CpG ODN7909 concentrations. Cellular colonization was evaluated using microscopy. Cell cycle distribution and apoptosis rate was determined with flow cytometry. Interleukin (IL)-12 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α concentrations were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

Hep-2 cells were found to express TLR9, and CpG ODN7909 treatment suppressed Hep-2 cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Cell survival curve analyses revealed a sensitivity enhancement ratio of the mean death dose of 1.225 for CpG ODN7909 plus irradiation versus irradiation alone. Furthermore, the population of Gap 2/mitotic-phase cells, apoptosis rate and secreted IL-12 and TNF-α levels were significantly increased in Hep-2 cells treated with CpG ODN7909 plus irradiation versus IR alone.

Conclusion

CpG ODN7909 enhanced the radiosensitivity of Hep-2 cells in vitro.

Keywords: CpG ODNs, radiosensitivity, Hep-2 cells, toll-like receptor 9, cell cycle, apoptosis

Introduction

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), a highly aggressive malignancy with 5-year overall survival of approximately 61%, is one of the most common malignant otolaryngology tumours and ranks second among cancers derived from epithelial cells in the head and neck.1–3 Radiotherapy is a clinically important treatment method for patients with LSCC, however, the mode of LSCC treatment is changing and increasing numbers of clinicians focus on how to preserve the function and original structure of the larynx. Recent years have seen a trend toward improved post-treatment voice quality in patients with early-stage LSCC treated with external radiation.4–7

Radiotherapy is not only an adjuvant treatment following surgery, but also an important treatment for patients with locally advanced LSCC who can’t undergo surgical resection or who have a strong desire to protect the larynx.8,9 Various studies have shown that irradiation (IR) combined with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu), may achieve better results compared with IR alone.10–13 Nevertheless, there remains a risk of recurrence and metastasis in some patients with LSCC, for whom the efficacy of re-irradiation is poor and radiation resistance is prone to occur, resulting in reduced quality of life and shorter life span.14 Hence, there is an urgent need to explore an effective radiosensitizer in the treatment of the patients with LSCC.

Recent studies have indicated that synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides containing unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motifs (CpG ODNs) may induce anti-tumour responses as immunoadjuvants in combination with other therapies, via interacting with toll-like receptors (TLRs) that play a fundamental role in the innate immune system.15–17 Moreover, a previous study by the present authors suggested that TLR9, recognized by CpG ODN7909, is also expressed in human non-small cell lung cancer (A549) cells, and CpG ODN7909 was shown to potentiate X-ray-induced inhibition of proliferation in this cell line.18 Nevertheless, the role of CpG ODN7909 on the radiosensitivity of human epidermoid cancer strain 2 (Hep-2) cells, a human laryngeal carcinoma-derived cell line, remains unclear.

In the present study, TLR9 expression, and the role of CpG ODN7909 on Hep-2 cell radiosensitivity, was assessed. The effects of CpG ODN7909 on cytokine secretion, cellular proliferation, cell cycle distribution and apoptosis was also investigated in the Hep-2 cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and CpG ODN7909

Hep-2 cells purchased from the Chinese Type Culture Collection (CTCC; Wuhan, China) were maintained in the following culture medium: Minimum essential medium (MEM; BioWest, Loire Valley, France) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin G, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. CpG ODN7909 (5′-TCGTCGTTTTGTCGTTTTGTCGTT-3′) was obtained from Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Services Limited Company (Sangon, Shanghai, China), dissolved in phosphate buffer saline (PBS; 0.01 M, pH 7.4) and maintained at –20°C until use.

Western blotting

Whole cells were lysed in protein lysis buffer with 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride. Total proteins were harvested by centrifugation (14 000 g for 15 min at 4°C), and protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford Assay. Briefly, equal amounts of proteins (50 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with monoclonal mouse anti-TLR9 antibody (1:1 000 dilution; Cell Signalling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase primary antibody (GAPDH;1:5 000 dilution; Cell Signalling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). After three washes with Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBS-T; pH 7.6; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1 % Tween 20), the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5 000 dilution; Kaiji, Jiangsu China) at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was finally washed three times with TBS-T. TLR9 protein levels were expressed as the optical density value of the target protein/GAPDH using a G:BOX ChemiXR5 gel doc system with Gel-Pro32 software (Syngene, Cambridge, UK).

Reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from 5 × 106 Hep-2 cells using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), then reverse transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturers' instructions. The cDNA was then amplified using the following TLR9 primer sequences: 5′-GCAAAGTGGGCG AGATGAGGAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GA GTGAGCGGAAG AAGATGC-3′ (reverse), with AccuPower® 2X Greenstar™ qPCR Master Mix (Bioneer Corporation, Daejeon, South Korea). PCR was preformed using the LightCycler® 480 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) with the following thermal-cycling conditions: 5 min at 95°C for pre-denaturation, followed by 32 cycles of 30 s at 95°C for denaturation, 30 s at 56°C for annealing, 45 s at 72°C for elongation, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The 578 bp reaction product was resolved by electrophoresis using a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed using an ultraviolet transilluminator.

Radiation exposure

Hep-2 cells were exposed to 6 MV X-rays using a linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) under the source-to-skin distance of 100 cm, with a dose rate of 2.0 Gy/min. Graded irradiated doses, ranging from 0 to 10 Gy, were used in Hep-2 clonogenic survival assays. For all other experiments, 10 Gy radiation was employed.

Detection of cell viability via cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8)

Each well of 96-well plates were seeded with 6 × 103 Hep-2 cells in 100 μl of culture medium. Various concentrations of CpG ODN7909 (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60 μg/ml) were added, and the cells incubated for 24 or 48 h at 37°C. Following CpG ODN7909 treatment, 10 μl of CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo Laboratories, Kami Mashiki-gun, Japan) was added to each well, and the cells incubated for a further 3 h at 37°C in the dark. Optical densities were then measured at 450 nm, and cell viability of CpG-treated cells was calculated as a proportion of the untreated cells, as follows: absorbance of CpG-treated cells/absorbance of untreated cells (0 μg/ml CpG ODN7909) × 100. Hep-2 cells were then seeded as before, and equally randomized into four groups, comprising: control group, CpG ODN7909-treated group (CpG group), irradiation group (IR group), and CpG ODN7909 + irradiation group (CpG + IR group). Based on the initial cell viability results, Hep-2 cells in the CpG and CpG + IR groups were treated with CpG ODN7909 at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and cells in all groups were cultured for 24 h. Following 24 h culture at 37°C, cells in the IR and CpG + IR groups were then exposed to 10 Gy radiation. A further 24 or 48 h following irradiation, cell viability was determined in all cells using the CCK-8 assay. All experiments were performed three times for each condition.

Clonogenic survival assay

Hep-2 cells were divided into two treatment groups and incubated for 24 h with or without CpG ODN7909 at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Cells were then irradiated with varying IR doses of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 Gy, and harvested using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution for 1–2 min at 37°C. Cells were then re-seeded into 60 mm dishes at 500–3 000 cells per dish, as previously described,19 in triplicate. Following incubation for 14 days, colonies were stained with crystal violet and fixed in methanol. The number of stained colonies (not less than 50 cells) was imaged and counted manually under a microscope. The clonogenic survival fraction (%) was calculated as follows: (irradiated cell colony numbers/unirradiated cell colony numbers) × 100. The radiobiological parameters (D0, N, Dq) were analysed with a single-hit multi-target model. D0 is the radiation dose that can reduce survival by a factor of 1/e in the exponential region of the curve, N is the extrapolation number or zero-dose extrapolate, Dq is the quasithreshold dose, Dq = D0 × ln N.20

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysed by flow cytometry

Hep-2 cells, growing in logarithmic phase in six-well plates, were divided into four treatment groups (control group, CpG group, IR group, and CpG + IR group) as above. After 24 and 48 h exposure to 10 Gy radiation (IR groups only), cells of each group were harvested. The cell cycle distribution (proportion of cells in Gap 2/Mitotic phase [G2/M]) was detected by measuring the DNA content stained with propidium iodide (PI; BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) in the presence of RNase, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, at 24 or 48 h post irradiation, Hep-2 cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA and centrifuged at 233 g at room temperature for 5 min. The cells were then fixed with 70% cold ethanol overnight at –20°C, then incubated with 500 μl of staining solution (containing 200 μl of RNase/PI) at room temperature for 15 min in the dark prior to flow cytometry. The proportion of apoptotic cells was determined using an annexin V fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA). Briefly, harvested cell pellets were resuspended in 190 μl binding buffer and stained with 5 μl of annexin V FITC and 5 μl of PI staining solution for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Cell cycle and apoptosis were evaluated by flow cytometry using a FACScan™ system with CellQuest™ software, version 3.3 (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The proportion of cells in G2/M phase was calculated as: (number of cells in G2/M phase/total number of cells) × 100. Apoptosis rate (%) was calculated as previously described:21 (number of apoptotic cells/total number of cells) × 100.

Measurement of interleukin (IL)-12 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α release

Hep-2 cells divided into four treatment groups were cultured in six-well plates and treated as above. At 24 or 48 h post-radiation, the cell culture supernatants were collected and stored at –80°C. Human IL-12 Valukine™ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit and Human TNF-alpha Valukine™ ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used to measure secreted IL-12 and TNF-α levels, respectively.

Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for data analyses and graph production. All data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. A single-hit multi-target model was used to fit colony counts to a clonogenic survival curve. Differences in cell viability, flow cytometric analyses or secreted cytokine levels between the treatment groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) multiple comparisons test. The two treatment groups in the clonogenic survival assay were analysed using Student’s t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of TLR9 in Hep-2 cells

Western blots and RT-PCR results showed that TLR9 was expressed in Hep-2 cells. The optical density value of TLR9/GAPDH was 0.55 (Figure 1a), and RT-PCR revealed a product of 578 bp, which corresponded to the expected TLR9 fragment size (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Expression of TLR9 in Hep-2 cells. (a) Representative image showing positive Western blot signal for TLR9 protein, with GAPDH as the loading control; and (b) Representative agarose gel image showing the TLR9 DNA fragment (approximately 578 bp) amplified using reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. TLR9, toll-like receptor 9; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Cell viability

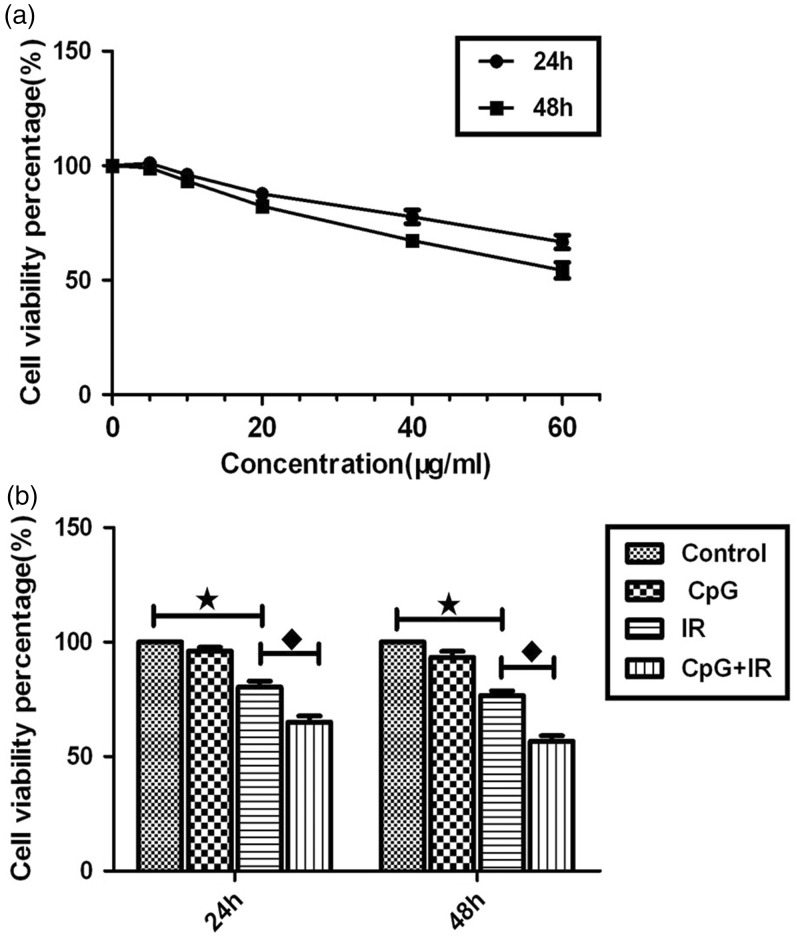

In Hep-2 cells treated with CpG ODN7909 at 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60 μg/ml, cell viability was shown to be inhibited in a dose-and time-dependent manner (P <0.01), displayed by a gradually increasing inhibitory effect with increasing CpG ODN7909 concentrations and lower cell viability at the higher concentrations between 24 and 48 h (Figure 2a). In Hep-2 cells with or without CpG ODN7909 treatment at 10 μg/ml, and with or without 10 Gy irradiation, cell viability decreased progressively with a statistically significant difference between the groups (F = 60.980, P <0.01 at 24 h and F = 80.159, P <0.01 at 48 h; Figure 2b). Compared with the control group, cell viability in the IR group was significantly lower (P <0.01 at both 24 and 48 h). Cell viability was also significantly lower in the CpG + IR group compared with IR alone (P <0.01 at both 24 and 48 h). There was no statistically significant difference in cell viability between the control group and Hep-2 cells treated with CpG ODN7909 alone (P = 0.205 at 24 h and P = 0.061 at 48 h; Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Effects of CpG ODN7909 (CpG) and irradiation (IR) on cell viability of Hep-2 cells quantified using cell counting kit-8 assays. (a) Cells were treated with CpG ODN7909 at concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60µg/ml and CCK-8 was added at 24 and 48 h following treatment; and (b) cell viability in different treatment groups (control, 10 µg/ml CpG ODN7909 only, 10 Gy irradiation at only, or 10 µg/ml CpG ODN7909 with 10 Gy irradiation). Data presented as mean ± SD; ★P <0.01, control group versus IR group; ♦P <0.01, IR group versus CpG + IR group (one-way analysis of variance using Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons test); CpG ODN, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides

Clonogenic survival analysis

Hep-2 cell dose-survival curves were fitted using a single-hit multi-target model (Figure 3). In Hep-2 cells treated with CpG ODN7909 plus IR, there were markedly lower values (P <0.05) for mean death dose (D0), quasi field dose (Dq), extrapolation number (N) and a narrower initial shoulder than in cells treated with IR alone, and the sensitivity enhancement ratio (SER)D0 was 1.225. These results suggest that CpG ODN7909 has radiation-enhancing effects in Hep-2 cells (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Dose-survival curves fitted using a multi-target single-hitting model to demonstrate the impact of CpG ODN 7909 on irradiation (IR) of Hep-2 cells. Hep-2 cells were irradiated with 6 MV X-rays at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 Gy with or without CpG ODN 7909 at 10 µg/ml (CpG + IR group). CpG + IR showed decreased clonogenic survival compared with IR alone (P <0.05; Student’s t-test). CpG ODN, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides

Table 1.

Comparison of radiosensitivity in Hep-2 cells treated with irradiation (IR) alone (6 MV X-rays at 10 Gy; IR group), or with irradiation plus unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides (CpG ODN)7909 (CpG + IR group)

| Group | N | D0 | Dq | SERD0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 4.394 | 1.892 | 2.801 | – |

| CpG + IR | 2.112 | 1.545 | 1.155 | 1.225 |

| Statistical significance | P <0.001 | P = 0.026 | P <0.001 | – |

The N, D0, and Dq values were significantly decreased relative in the CpG + IR group than in the IR group (all P <0.05; Student’s t-test).

N, extrapolation number; D0, mean death dose; Dq, quasi field dose; SER, sensitivity enhancement ratio.

Cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase

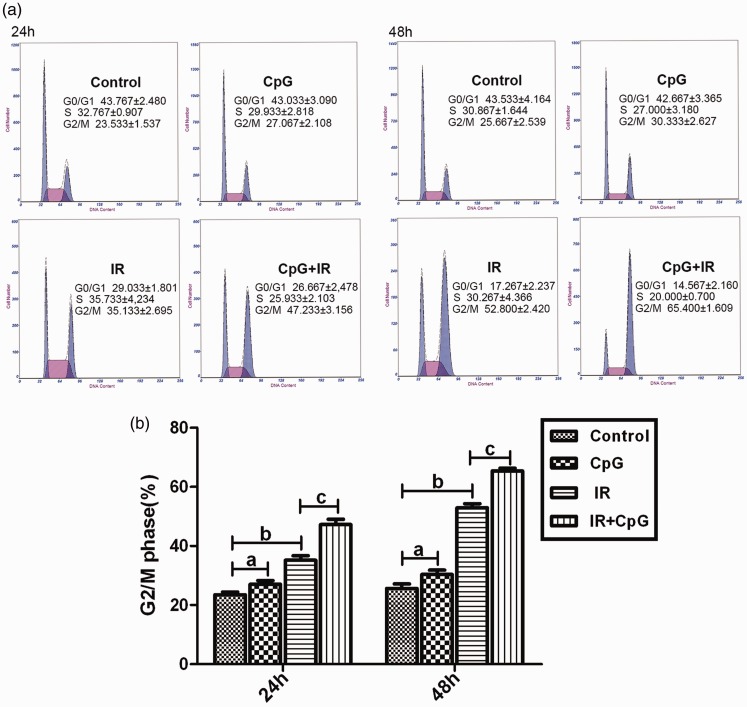

Proportions of Hep-2 cells in G2/M phase cell cycle arrest were significantly different between the four treatment groups (untreated control, CpG ODN 7909 only, IR only, or CpG ODN 7909 plus IR; F = 55.211, P <0.01 at 24 h and F = 191.341, P <0.01 at 48 h; Figure 4a and b). Compared with the control group, a significant increase in the percentage of Hep-2 cells in the G2/M phase was observed in the CpG group (P <0.05 at both 24 and 48 h) and the IR group (P <0.05 and P <0.01 at both 24 and 48 h). Moreover, at 24 and 48 h following IR, the percentage of cells in G2/M phase was significantly higher in the CpG + IR group than in the IR alone group (P <0.01 at both 24 and 48 h; Figure 4a and b).

Figure 4.

Hep-2 cell cycle assessment by flow cytometry, showing: (a) Representative flow cytometry results at 24 and 48 h following no treatment (control) or treatment with CpG ODN7909 alone (CpG group), irradiation alone (IR group) or CpG plus IR; (b) The proportion of cells in G2/M phase in the four treatment groups. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments, and are presented as mean ± SD; aP >0.05, control group versus CpG group; bP <0.01, control group versus IR group; cP <0.01, IR group versus CpG + IR group (one-way analysis of variance using Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons test); G0, stationary phase; G1, first gap; M, mitosis; G2, second gap; IR, irradiation; CpG ODN, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides

Increase of IR-induced cellular apoptosis

Significant differences were observed in Hep-2 cell apoptosis index between the four treatment groups (F = 454.198, P <0.01 at 24 h and F = 301.354, P <0.01 at 48 h; Figure 5a and b). Compared with the control group, the Hep-2 cell apoptosis index was significantly increased in the IR group (P <0.01 at 24 and 48 h) and the CpG + IR group (P <0.01 at 24 and 48 h). Moreover, the proportion of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in Hep-2 cells treated with CpG ODN 7909 plus IR versus IR alone (P <0.01 at 24 and 48 h). The cellular apoptosis index remained similar between the control group and cells treated with CpG ODN 7909 alone (P = 0.468 at 24 h and P = 0.847 at 48 h; Figure 5a and b).

Figure 5.

Analysis of apoptotic Hep-2 cells using annexin V/PI and flow cytometry: (a) Representative flow cytometry results at 24 and 48 h following no treatment (control) or treatment with CpG ODN7909 alone (CpG group), irradiation alone (IR group) or CpG plus IR showing B1, dead cells; B2, late apoptosis; B3, viable cells; and B4, early apoptotic cells; (b) Apoptotic fraction of cells in the four different treatment groups; Data presented as mean ± SD; ano statistically significant difference (P >0.05), control group versus CpG group; bP <0.01, control group versus IR group; cP <0.01, IR group versus CpG + IR group (one-way analysis of variance using Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons test); PI, propidium iodide; CpG ODN, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides

Release of IL-12 and TNF-α

A significant difference was observed in IL-12 concentration between the four treatment groups (F = 13.166, P <0.01 at 24 h and F = 16.047, P<0.01 at 48 h). Compared with the control group, secreted IL-12 concentration was higher in the CpG group (21.181 ± 0.647 pg/ml versus 18.842±0.981 pg/ml at 24 h, P <0.05; and 19.420 ± 1.165 pg/ml versus 16.165 ± 0.931 pg/ml at 48 h, P <0.05). In addition, IL-12 concentration was significantly higher in the CpG + IR group verses IR alone (24.501 ± 1.490 pg/ml versus 18.936 ± 1.394 pg/ml at 24 h, P <0.01; and 21.616 ± 0.780 pg/ml versus 17.557 ± 1.218 pg/ml at 48 h, P <0.01; Figure 6a). A significant difference was also observed in the TNF-α concentration between the four treatment groups (F = 18,843, P <0.01 at 24 h and F = 21.574, P <0.01 at 48 h). Compared with the control group, secreted TNF-α concentration was higher in the CpG group (28.340 ± 0.993 pg/ml versus 24.456 ± 1.440 pg/ml at 24 h, P <0.05; and 23.303 ± 0.975 pg/ml versus 20.079 ± 0.927 pg/ml at 48 h, P <0.05). Secreted TNF-α concentration was also significantly higher in the CpG + IR group versus IR alone (32.035 ± 1.714 pg/ml versus 25.638 ± 1.109 pg/ml at 24 h, P <0.01; and 25.923 ± 1.011 pg/ml versus 20.667 ± 1.081 pg/ml at 48 h, P<0.01; Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Interleukin (IL)-12 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α release by Hep-2 cells measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: (a) Cell culture supernatant IL-12 concentrations in four groups at 24 and 48 h following no treatment (control) or treatment with CpG ODN7909 alone (CpG group), irradiation alone (IR group) or CpG plus IR; (b) Cell culture supernatant TNF-α concentrations in the four treatment groups; Data presented as mean ± SD; ⋆P <0.05, control group versus CpG group; ⋄P <0.01, IR group versus CpG + IR group (one-way analysis of variance using Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons test); CpG ODN, unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motif oligodeoxyribonucleotides

Discussion

The application of CpG ODNs, which recognize TLR9, has shown a remarkable degree of synergy with conventional remedies for malignant tumours.22–25 In the past, TLR9 was mainly reported to be expressed in various immune cells, including dendritic cells.26 More recently, increasing evidence has shown that TLR9 is also expressed in tumour tissues, which display higher levels of TLR9 than normal tissues.27,28 For example, TLR9 mRNA expression was found to be higher in non-small cell lung carcinoma than in normal lung tissue,29 and TLR9 expression was higher in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma tumour tissue compared with adjacent normal tissues at the gene and protein level.30 Furthermore, this change in TLR9 was positively correlated with clinical stage.30 The presence of TLR9 has also been reported at the mRNA and protein level in Hep-2 cell lines by means of RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry.31 Similarly, the present study also showed that TLR9 was expressed in Hep-2 cells, which might be involved in enhancing the radiosensitivity shown in the present study, possibly via mediation of CpG ODN7909 intracellular signal transduction.

The occurrence, infiltration and metastases of tumours is related to cell proliferation, and CCK-8 can be used to evaluate cell proliferation dynamics.32 The present results showed a decrease in CCK-8 after Hep-2 cells were exposed to CpG ODN7909 for 24 and 48 h, indicating that cellular viability was inhibited, and this inhibition was shown to be in a dose-dependent with increasing CpG ODN7909 concentrations. In addition, the subtoxic dose of CpG ODN7909 (at 10 μg/ml) combined with 10 Gy X-ray radiation was shown to significantly enhance the decrease in cell viability compared with 10 Gy X-ray radiation alone. Consistent with the present results, the authors previously published study demonstrated that CpG ODN1826 alone could delay the growth of Lewis lung carcinoma in mice, and the combined inhibitory effect of CpG ODN1826 and X-ray on Lewis lung cancer was greater than X-ray radiation alone.33 The present study also employed clonogenic survival analysis to investigate the role of CpG ODN7909 on radiation sensitivity in Hep-2 cells, and showed that CpG ODN7909 combined with radiation was able to significantly inhibit Hep-2 cell colony formation. Compared with the IR group, D0 of the combined treatment group was 1.545 Gy versus 1.892 Gy, the N value was 2.112 versus 4.394, and Dq value was 1.155 versus 2.801, indicating that CpG ODN7909 could enhance the in vitro sensitivity of Hep-2 cells to X-rays.

Cell cycle distribution is well documented to relate to radiosensitivity, with cells being the most sensitive to radiation during the G2/M phase and the least sensitive at the end of S phase.34 Therefore, mediating cell cycle progression into G2/M phase would be an effective approach to increase the radiosensitivity of tumours. CpG ODN has been reported to directly act on the human lung carcinoma cell line 95D by promoting cancer cells to move into the G2/M phase, and the signalling pathway was shown to be mediated by TLR9.35 Consistent with these results, the present study showed that CpG ODN7909 significantly potentiated X-ray induced cell-cycle arrest, and the number of cells arrested at G2/M phase was significantly increased in cells treated with CpG ODN7909 and X-ray combined, compared with X-ray alone.

Apoptosis induced by irradiation is vital in the use of X-rays to eliminate tumour cells, and it is widely recognized that irradiation-induced apoptosis may be used for assessing the sensitivity of tumour cells to irradiation, with an increased apoptotic rate indicating higher tumour cell radiosensitivity.36 In the present study, CpG ODN7909 alone at 10 μg/ml could not directly induce cellular apoptosis, but the apoptotic index was significantly increased when CpG ODN7909 was combined with radiation. The mechanism may be that CpG ODN7909 combined with radiation altered the cell cycle distribution, with cell arrest at G2/M phase, in which the cells were more sensitive to radiation and were more likely to enter the apoptotic pathway.

Furthermore, the present study showed that at 24 and 48 h following irradiation, IL-12 and TNF-α secretion by Hep-2 cells was significantly increased in cells treated with CpG ODN7909 and X-rays combined compared with X-rays alone. IL-12 is known to play a significant role in inhibiting tumour development and metastasis,37 and TNF-α is a cell factor with strong direct antitumour activity, that is reported to be closely involved with radiation sensitivity.38 TNF-α has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of various tumour cells, and to induce apoptosis.39,40 One study showed that IL-12 and TNF-α could be up-regulated in the human glioma cell line (CHG-5) when these cells were treated with a combination of CpG ODN and ß-rays, which apparently inhibited cell clonogenic survival.41 Similarly, the present results showed that secretion of IL-12 and TNF-α had an increasing trend following treatment with CpG ODN7909. The secretion of IL-12 and TNF-α was increased more significantly following treatment with CpG ODN7909 and X-rays combined. The present authors hypothesize that Hep-2 cells can secrete these factors through autocrine mechanisms, and these factors may participate in improving the roles of CpG ODN7909 on radiosensitivity of tumour cells.

In conclusion, the present results showed that CpG ODN7909 combined with X-ray radiation decreased cellular clonogenic survival and increased cellular apoptosis, percentage of cells at G2/M phase and secretion of specific cytokines, compared with X-ray radiation alone, suggesting that CpG ODN7909 could enhance the radiosensitivity of Hep-2 cells in vitro. These results may provide a clinical perspective for improvement of radiotherapy treatment effects in patients with LSCC. However, the precise mechanisms by which TLR9 may mediate signal transduction pathways related to radiosensitivity remain unclear, and require further studies.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the Jinshan District Health and Family Planning Commission Project (No. JSKJ-KTQN-2014-01).

References

- 1.Rudolph E, Dyckhoff G, Becher H, et al. Effects of tumour stage, comorbidity and therapy on survival of laryngeal cancer patients: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2011; 268: 165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 1921–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habbous S, Harland LT, La Delfa A, et al. Comorbidity and prognosis in head and neck cancers: Differences by subsite, stage, and human papillomavirus status. Head Neck 2014; 36: 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins KM, Shah MD, Ogaick MJ, et al. Treatment of early-stage glottic cancer: meta-analysis comparison of laser excision versus radiotherapy. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 38: 603–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng Z, Li Y, Jin L, et al. Retrospective analysis of therapeutic effect and prognostic factors on early glottic carcinoma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2016; 15: 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greulich MT, Parker NP, Lee P, et al. Voice outcomes following radiation versus laser microsurgery for T1 glottic carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 152: 811–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdurehim Y, Hua Z, Yasin Y, et al. Transoral laser surgery versus radiotherapy: systematic review and meta-analysis for treatment options of T1a glottic cancer. Head Neck 2012; 34: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forastiere AA Weber RS andTrotti. A. Organ preservation for advanced larynx cancer: issues and outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3262–3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grover S, Swisher-McClure S, Mitra N, et al. Total laryngectomy versus larynx preservation for T4a larynx cancer: patterns of care and survival outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015; 92: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper JS, Zhang Q, Pajak TF, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/intergroup phase III trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 84:1198–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason KA, Ariga H, Neal R, et al. Targeting toll-like receptor 9 with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhances tumor response to fractionated radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehm A, Lindner F, Wichmann G, et al. Impact of indication-shift of primary and adjuvant chemo radiation in advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2015; 272: 2017–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popovtzer A, Burnstein H, Stemmer S, et al. Phase II organ-preservation trial: concurrent cisplatin and radiotherapy for advanced laryngeal cancer after response to docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil-based induction chemotherapy. Head Neck 2017; 39: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen AM Phillips TL andLee NY.. Practical considerations in the re-irradiation of recurrent and second primary head-and-neck cancer: who, why, how, and how much? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 81:1211–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin P, Liu X, Mansfield AS, et al. CpG-induced antitumor immunity requires IL-12 in expansion of effector cells and down-regulation of PD-1. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 70223–70231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia Y, Gupta GK, Castano AP, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide as immune adjuvant enhances photodynamic therapy response in murine metastatic breast cancer. J Biophotonics 2014; 7: 897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruan M, Thorn K, Liu S, et al. The secretion of IL-6 by CpG-ODN- treated cancer cells promotes T-cell immune responses partly through the TLR-9/AP-1 pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2014; 44: 2103–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zha L, Qiao T, Yuan S, et al. Enhancement of radiosensitivity by CpG- oligodeoxyribonucleotide-7909 in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2010; 25: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Short SC, Giampieri S, Worku M, et al. Rad51 inhibition is an effective means of targeting DNA repair in glioma models and CD133+ tumor-derived cells. Neuro Oncol 2011; 13: 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shipley WU, Stanley JA, Courtenay VD, et al. Repair of radiation damage in lewis lung carcinoma cells following in situ treatment with fast neutrons and γ-rays. Cancer Res 1975; 35: 932–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou HB, Chen JM, Cai JT, et al. Anticancer activity of genistein on implanted tumor of human SG7901 cells in nude mice. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen W, Liu X, Qiao T, et al. Impact of CHK2-small interfering RNA on CpG ODN7909-enhanced radiosensitivity in lung cancer A549 cells. Onco Targets Ther 2012; 5:425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan L, Xu G, Qiao T, et al. CpG-ODN 7909 increases radiation sensitivity of radiation-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cell line by overexpression of toll-like receptor 9. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2013; 28: 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason KA, Ariga H, Neal R, et al. Targeting toll-like receptor 9 with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhances tumor response to fractionated radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrangolini G Tortoreto M andPerego P.. Combination of metronomic gimatecan and CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides against an orthotopic pancreatic cancer xenograft. Cancer Biol Ther 2008; 7: 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer S andWagner H.. Bacterial CpG-DNA licenses TLR9. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2002; 270: 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka J, Sugimoto K, Shiraki K, et al. Functional cell surface expression of toll-like receptor 9 promotes cell proliferation and survival in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Int J Oncol 2010; 37: 805–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrell MA Ilvesaro JM andLehtonen N.. Toll-like receptor 9 agonists promote cellular invasion by increasing matrix metalloproteinase activity. Mol Cancer Res 2006; 4: 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samara KD, Antoniou KM, Karagiannis K, et al. Expression profiles of Toll-like receptors in non-small cell lung cancer and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Oncol 2012; 40: 1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L Zhu D andDong Z.. Expression and Clinical value of Toll-like receptor 9 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Zhongguo Lao Nian Xue Za Zhi 2008; 28: 661–664. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sikora J, Frydrychowicz M, Kaczmarek M, et al. TLR receptors in laryngeal carcinoma - immunophenotypic, molecular and functional studies. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2010; 48: 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu T, Zhong L, Gan L, et al. Effects of LG268 on cell proliferation and apoptosis of NB4 cells. Int J Med Sci 2016; 13: 517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuang X, Qiao T, Yuan S, et al. Dose-effect relationship of CpG oligodeoxyribonucleotide 1826 in murine Lewis lung cancer treated with irradiation. Onco Targets Ther 2013; 6: 549–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biade S Stobbe CC andChapman JD.. The intrinsic radiosensitivity of some human tumor cells throughout their cell cycles. Radiat Res 1997; 147: 416–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Wang C, Wen Z, et al. Selective up-regulation of CDK2 is critical for TLR9 signaling stimulated proliferation of human lung cancer cell. Immunol Lett 2010; 127: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan S Qiao T andChen W.. CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 1826 enhances the Lewis lung cancer response to radiotherapy in murine tumor. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2011; 26: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuzhalin AE andKutikhin AG.. Interleukin-12: clinical usage and molecular markers of cancer susceptibility. Growth Factors 2012; 30: 176–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi JY, Jung YJ, Choi SS, et al. TNF-alpha downregulates E-cadherin and sensitizes response to gamma-irradiation in Caco-2 cells. Cancer Res Treat 2009; 41: 164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wajant H. The role of TNF in cancer. Results Probl Cell Differ 2009; 49: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kianmanesh A, Hackett NR, Lee JM, et al. Intratumoral administration of low doses of an adenovirus vector encoding tumor necrosis factor alpha together with naive dendritic cells elicits significant suppression of tumor growth without toxicity. Hum Gene Ther 2001; 12: 2035–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan W, Ding F, Li B, et al. Study of CpG ODN107 on the radiosensitivity of human glioma cell line CHG-5. Zhong Hua Zhong Liu Fang Zhi Za Zhi 2007; 14: 481–484. [Google Scholar]