SUMMARY

Functional and anatomical sexual dimorphisms in the brain are either the result of cells that are generated only in one sex, or a manifestation of sex-specific differentiation of neurons present in both sexes. The PHC neurons of the nematode C. elegans differentiate in a strikingly sex-specific manner. While in hermaphrodites the PHC neurons display a canonical pattern of synaptic connectivity similar to that of other sensory neurons, PHC differentiates into a densely connected hub sensory/interneuron in males, integrating a large number of male-specific synaptic inputs and conveying them to both male-specific and sex-shared circuitry. We show that the differentiation into such a hub neuron involves the sex-specific scaling of several components of the synaptic vesicle machinery, including the vesicular glutamate transporter eat-4/VGLUT, induction of neuropeptide expression, changes in axonal projection morphology and a switch in neuronal function. We demonstrate that these molecular and anatomical remodeling events are controlled cell-autonomously by the phylogenetically conserved Doublesex homolog dmd-3, which is both required and sufficient for sex-specific PHC differentiation. Cellular specificity of dmd-3 action is ensured by its collaboration with non-sex specific terminal selector-type transcription factors whereas sex-specificity of dmd-3 action is ensured by the hermaphrodite-specific, transcriptional master regulator of hermaphroditic cell identity, tra-1, which represses transcription of dmd-3 in hermaphrodite PHC. Taken together, our studies provide mechanistic insights into how neurons are specified in a sexually dimorphic manner.

INTRODUCTION

Male and female brains display sexual dimorphisms on the level of function, anatomy and gene expression. In theory, such dimorphisms can be a reflection of two distinct scenarios, one in which dimorphisms are the result of the presence of neurons exclusively in one sex but not the other, and another in which neurons are present in both sexes (“sex-shared neurons”) but acquire sex-specific features [1, 2]. These scenarios are hard to untangle in vertebrate nervous systems, since their cellular complexity confounds the visualization and systematic comparison of individual neuron types between the two sexes. In contrast, clear evidence exists for both scenarios in the Drosophila nervous system, that is, both sex-specific neurons, as well as sex-specific anatomical features of sex-shared neurons have been unambiguously mapped [1–5]. However, dimorphic features of shared neurons have so far been only studied on a relatively coarse level and, aside from the well-characterized sex-specific regulatory factors Fruitless and Doublesex [2], there are relatively few molecular and functional features that have been mapped onto sex-shared, but sexually dimorphic neurons.

In the nematode C. elegans, sexually dimorphic features have been analyzed with unprecedented anatomical and molecular resolution. Like in other organisms, the C. elegans nervous system contains sex-specific neurons found exclusively in either the male or the hermaphrodite (a somatic female)[6, 7]. Moreover, there are neurons present in both sexes that share an identical lineage history, position, molecular features and overall appearance but that display sexually dimorphic synaptic connectivity patterns [8, 9]. In one set of striking examples, the sex-shared phasmid neurons PHA and PHB connect in a sexually dimorphic manner to distinct downstream interneurons which are also sex-shared [8, 9].

Apart from sexual dimorphisms of synaptic connectivity between sex-shared neurons, there are also sexually dimorphic synaptic connections between sex-shared neurons and sex-specific neurons [8]. Relatively few sex-shared neurons receive synapses from sex-specific neurons and these neurons can be considered “hub neurons” since they connect sex-specific network modules to the shared and non-sex specific “core nervous system” [8]. The most remarkable examples of such hub neurons are the PHC sensory neuron, and the DD6 and PDB motorneurons. All three neurons are sex-shared and receive a tremendous amount of additional synapses from male-specific neurons [8]. PHC stands out among those, because unlike DD6 and PDB, it is not a motor neuron that directly connects male-specific sensory inputs into muscle. As schematically diagrammed in Fig. 1A, PHC rather connects in a sexually dimorphic manner to a diverse set of inter- and motorneurons and of all neurons in the animal, it is the neuron that receives the most male-specific synaptic inputs from a variety of different sensory neurons. This is in notable contrast to the synaptic connectivity of PHC in hermaphrodites, where PHC appears to be a canonical sensory neuron receiving few synaptic inputs and generating modest outputs on a number of interneurons (Fig. 1A)[9]. Taken together, PHC undergoes a sexual differentiation process in males that transforms this neuron from a conventional sensory neuron to a hub neuron with sensory and interneuron properties. In this manuscript we assign sex-specific functions to PHC, describe a number of distinct molecular features of the PHC neurons, which parallel its differentiation into a hub neuron and identify a transcription factor required and sufficient for male-specific differentiation of PHC into a hub neuron.

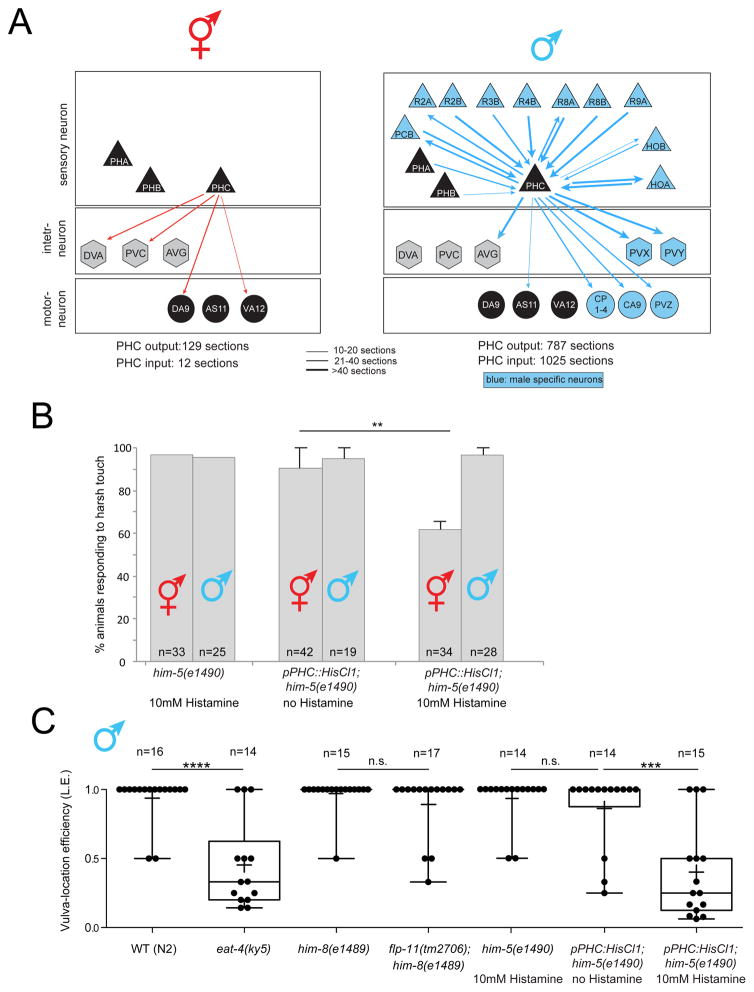

Fig. 1. Dimorphic synaptic connectivity and function of PHC.

A: Schematic synaptic connectivity. Edge weights were collected from www.wormwiring.org [8]. Only connections that directly involve PHC are shown.

B: PHC is required in hermaphrodites for response to harsh (picking-force) touch to the tail. Bar graph indicates the mean percentage of animals responding to harsh touch, with error bars indicating the minimum and maximum from two experimental replicates. Significance was calculated using Fisher’s exact test. ** p<0.01, n.s. p>0.05. “n” in each column indicates the total number of animals assayed.

C: PHC is required for a specific step of the male mating behavior, vulva search behavior. Mutant and Histamine-silenced animals tested for the male’s vulva location efficiency. Box plot representation of the data is shown, with whiskers pointing from min to max. Median and mean values are indicated by horizontal line and “+”, respectively. Statistics was calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.0005. “n” above graphs indicates the total number of animals assayed.

RESULTS

Sex-specific differences in PHC neuron function

We first set out to define a behavioral consequence of the sex-specific wiring of the PHC neuron. We generated transgenic animals in which the PHC neurons can be silenced in an inducible manner with a histamine-gated chloride channel [10]. Based on its direct innervation of command interneurons, a unique feature of several, previously described nociceptive neurons [9, 11], we tested the response of these transgenic animals to nociceptive stimuli and found that silencing of PHC results in defects in the response to harsh touch applied to the tail of the hermaphrodite (Fig. 1B). In contrast, silencing of PHC in males has no effect on the tail harsh touch response, suggesting that another neuron is now responsible for this response in the male tail and consistent with the absence of PHC innervation of command interneurons in males (Fig. 1A).

We found that male PHC becomes repurposed for male mating behavior since PHC silenced males show profound defects in vulva location behavior. Instead of stopping when the male tail has reached the vulva, PHC-silenced animals continue to search for the vulva (Fig. 1C). This phenotypic defect is consistent with the male-specific PHC wiring pattern: two sensory neurons that innervate PHC (PHB and HOA), as well as an interneuron (AVG) innervated by all three of these sensory neurons were previously shown to be involved in the same vulval stop behavior [12, 13]. Similar defects can be observed upon genetically disrupting the neurotransmitter system, glutamate, used by all these neurons (PHB, PHC, HOA) (Fig. 1C).

Sex-specific, cell-autonomous morphological differentiation of the PHC neurons

Having established a sex-specific function of PHC, we set out to define the sex-specific differentiation program of PHC in more detail. The electron micrographic analysis of two adult hermaphrodite tails and one adult male tail indicates that apart from their notably distinct synaptic connectivity patterns, the PHC neurons display different axon and dendrite lengths [8, 9, 14]. We used a reporter transgene to visualize the sexually dimorphic morphology of PHC in a larger cohort of animals, and we examined its previously undocumented dynamic differentiation during larval stages (Fig. 2A). We find that before sexual maturation, up until the L3 stage, the PHC dendrite extends into the tail tip of both sexes (Fig. 2A, purple arrow). During retraction and remodeling of the male tail hypodermis, the PHC dendrite then retracts and meanders (Fig. 2A). The PHC axons extend initially only into the pre-anal ganglion of both sexes. However, beginning at L4 stage, when male-specific neurons are generated and start to differentiate, the axon of male but not hermaphrodite PHC extends significantly beyond the pre-anal ganglion into the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 2A, B), to gather synaptic inputs from male-specific neurons and innervate newly generated male-specific motor neurons as well as sex-shared neurons (Fig. 1A)[8].

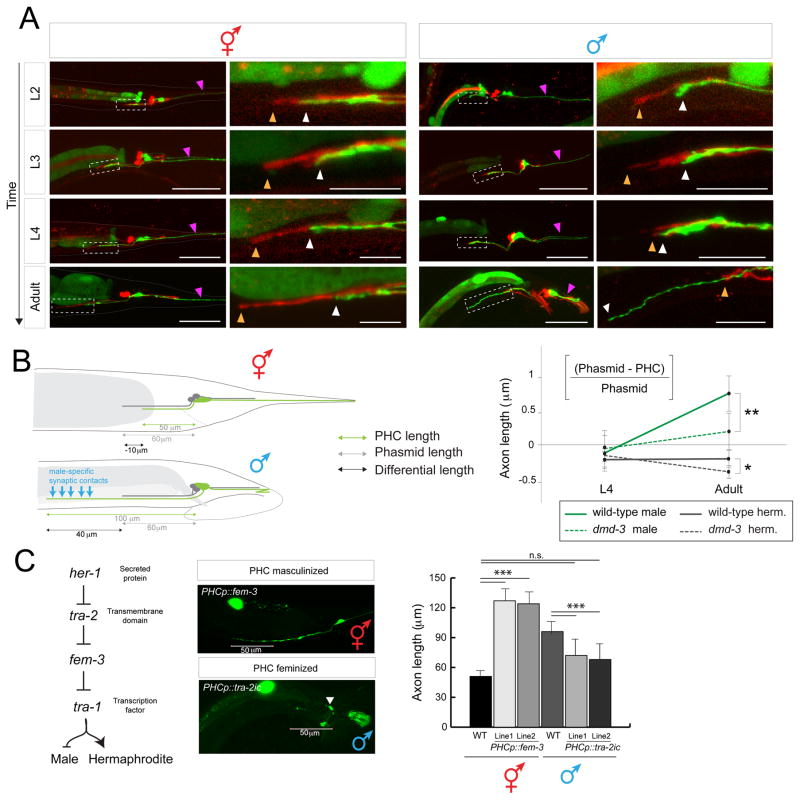

Fig. 2. Sexually dimorphic extension of the PHC axon.

A: PHC axon and dendrite morphology at different developmental stages. PHC was visualized with the transgene otEx6776, which expresses gfp under the control of the eat-4prom11Δ12 driver, which expresses in PHC of both males and hermaphrodites (described in more detail in Fig. 5). As landmark, the PHA and PHB neurons, which do not noticeably change morphology between the sexes, are filled with DiD (termination point of PHA/B marked with orange arrowhead, PHC with white arrowhead). PHC dendrites are marked with purple arrowhead. Scale bar: 50 μm. Dashed box indicates the area that is magnified in the right column. Scale bar in magnified panels: 10 μm.

B: Summary of PHC axon extension. Male specific synaptic contacts (referring to both inputs and outputs) are schematically indicated with blue arrows.

C: Male-specific axon extension is controlled cell-autonomously as determined by cell-specific sex change via manipulation of the sex-determination pathway. Transgenic array names: otIs520 (eat-4prom11::gfp) was crossed with PHCp::fem-3 (lines otEx6879 and otEx6980) and PHCp::tra-2ic (lines otEx6881 and oEx6882) strains. PHCp = eat-4prom11Δ11 driver (Fig. 5B). Significance was calculated using student t-test, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005 and *P < 0.01. n.s. >0.1

We asked whether this sex-specific extension of the PHC axons depends on male-specific synaptic targets which may secrete attractive cue(s) or on any other male-specific structure or whether sex-specific PHC axon extension is controlled in a cell-autonomous manner. To this end, we altered the sex of PHC in a cell-autonomous manner through manipulation of the activity of the Gli transcription factor TRA-1, the master regulator of sexual differentiation [15, 16]. TRA-1 is expressed in all hermaphroditic cells and required autonomously to promote hermaphroditic cellular identities and repress male identities [17]. In males, TRA-1 is downregulated via protein degradation (Fig. 2C)[18, 19]. We feminized male PHC through PHC-specific expression (eat-4prom11Δ11 driver, from now on called PHCp) of the intracellular domain of TRA-2, tra-2ic, which constitutively signals to prevent TRA-1 downregulation by FEM-3 and other factors [20, 21]. We find that in otherwise male animals this cell-autonomous feminization results in a failure of the PHC axon to undergo its characteristic extension through the pre-anal ganglion (Fig. 2C). Conversely, masculinization of PHC via fem-3-mediated degradation of TRA-1 protein in otherwise hermaphroditic animals results in a male-like extension of the PHC axon (Fig. 2C). These sex-reversal experiments confirm cell autonomy but also suggest that (1) the TRA-1 transcription factor represses a male morphological differentiation program in PHC and (2) that TRA-1 is both required and sufficient to control the male-specific features of PHC.

Transcriptional scaling of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the male PHC neuron

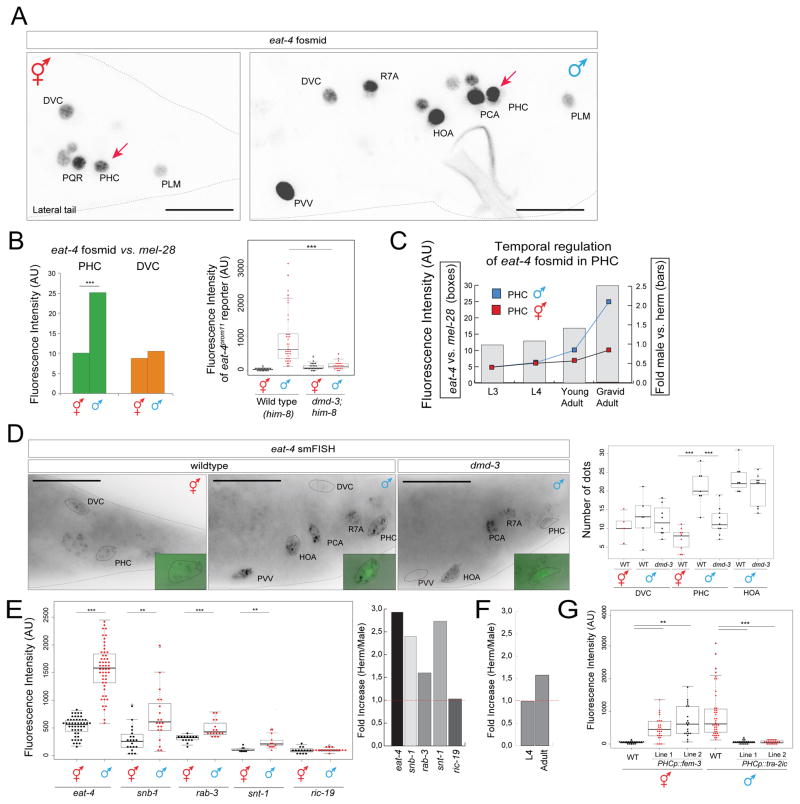

We find that sex-specific morphological changes of the PHC neurons are paralleled by a change in a number of molecular features. Specifically, the expression of the vesicular glutamate transporter eat-4/VGLUT is strongly upregulated in PHC, as assessed with a fosmid reporter construct (Fig. 3A). We quantified this upregulation through normalization of eat-4/VGLUT expression relative to eat-4/VGLUT expression in other neurons, and also relative to a ubiquitously expressed nuclear envelope protein-encoding gene, mel-28 (Fig. 3B). We independently validated this upregulation using quantitative single mRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH)(Fig. 3D). Both reporter gene and smFISH analysis indicate a three-fold upregulation in eat-4/VGLUT expression in male PHCs (Fig. 3). This upregulation begins at the late L4/young adult stage (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Scaling of synaptic vesicle components in PHC.

A: eat-4/VGLUT fosmid reporter expression (otIs518) in the adult male tail. The complete set of all male-specific, eat-4/VGLUT-expressing neurons will be reported elsewhere. Scale bar: 20μm.

B: eat-4/VGLUT fosmid (otIs518) reporter expression measured by absolute fluorescence (right panel) and normalized to expression of the mel-28 nuclear envelope protein (bq5). otIs520 reporter expression measured by absolute fluorescence in him-8(e1489) background and dmd-3(tm2863);him-8(e1489) (left panel).

C: Temporal dynamics of scaling of eat-4/VGLUT fosmid (otIs518) reporter expression.

D: smFISH analysis of endogenous eat-4/VGLUT expression in young adult animals. PHC was marked with otIs520 (green). See Fig. S2 for eat-4 smFISH probe specificity. Scale bar: 20μm.

E,F: Scaling of transcription of other vesicular markers, as assessed by SL2-based fosmid reporter expression [33]. Temporal dynamic of rab-3 fosmid (otIs498) expression in L4 vs. adult animals (F).

G: eat-4/VGLUT scaling is controlled cell-autonomously as shown by masculinization and feminization experiments. otIs520 (eat-4prom11::gfp) was crossed with PHCp::fem-3 (lines otEx6879 and otEx6980) and with PHCp::tra-2ic (lines otEx6881 and oEx6882) strains. PHCp (eat-4prom11Δ11 driver). Wildtype data showing in this plot is same as in panel B (left panel), genotypes were scored in parallel. Significance was calculated using student t-test, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. See Fig. S1 for more regulators of eat-4 expression.

The increase in eat-4/VGLUT expression and synaptic output is accompanied by the male-specific transcriptional upregulation of other synaptic proteins including synaptotagmin (snt-1), synaptobrevin (snb-1) and Rab-3 (rab-3) (Fig. 3E,F). ric-19/ICA69, a gene involved in dense core vesicle mediated secretion, is not upregulated (Fig. 3E). Taken together, we define here a previously unrecognized transcriptional scaling phenomenon in which the generation of novel synaptic contact is mirrored by a neuron-type specific transcriptional upregulation of vesicular proteins.

We again used cell-specific sex reversal experiments to test whether the scaling of synaptic vesicle machinery requires the presence of the entire male-specific circuitry that PHC becomes wired into or whether it is controlled cell autonomously, like PHC axon extension. We find that masculinization of PHC via fem-3-mediated degradation of TRA-1 in otherwise hermaphroditic animals results in scaling of eat-4/VGLUT expression (Fig. 3G). Conversely, feminization of PHC in otherwise male animals using the intracellular domain of TRA-2, tra-2ic, expressed specifically in PHC, results in a failure to upregulate eat-4/VGLUT expression (Fig. 3G).

Sexually dimorphic neuropeptide expression in PHC

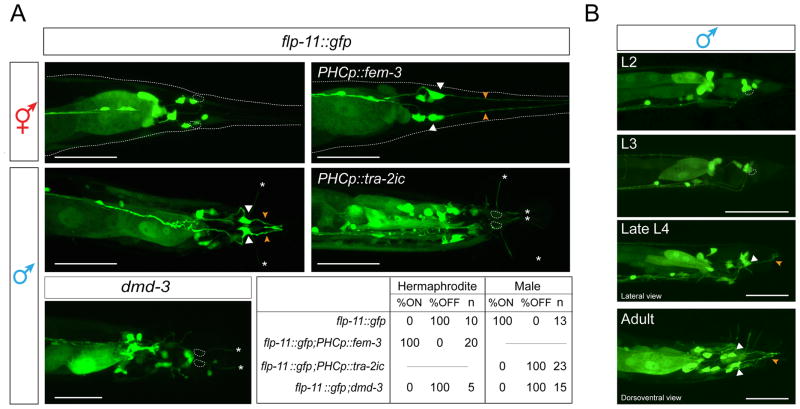

Fast synaptic transmission machinery is not the only neurotransmission-related feature that becomes modulated in male PHC. We found that a FMRFamide neuropeptide-encoding gene, flp-11 (which encodes at least four different phylogenetically conserved peptides [22]) is expressed exclusively in PHC in adult males (Fig. 4A). flp-11 is not expressed in either sex in early larval stages (L2, L3), after the birth of PHC in the L1 stage and before sexual maturation, but it becomes activated specifically in PHC in L4 males (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Sexually dimorphic neuropeptide expression in PHC.

A: flp-11 reporter expression (ynIs40) in wildtype hermaphrodites and males, in animals in which the sex of PHC was changed via fem-3 or tra-2ic expression and in dmd-3(tm2863) mutants. The table indicates the percentage of neurons that show expression of the flp-11 reporter in the different conditions assayed. N=number of animals. Scale bar: 50 μm.

B: Temporal dynamics of flp-11 reporter gene expression in larval and adult male stages. Cell bodies are labeled with white arrow, dendritic projections with orange arrow. White asterisks indicate ray projections. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Like PHC axon extension and scaling of synaptic vesicle machinery, the male-specific induction of flp-11 expression is controlled cell-autonomously. Masculinization of PHC via fem-3-mediated degradation of TRA-1 in otherwise hermaphroditic animals results in induction of flp-11 expression (Fig. 4A) and, conversely, feminization of PHC in otherwise male animals using the intracellular domain of TRA-2, tra-2ic, expressed specifically in PHC, results in a failure to induce flp-11 expression (Fig. 4A).

flp-11 mutants do not display defects in the vulva location behavior controlled by PHC (Fig. 1C), suggesting either redundancy of flp-11 function with other neuropeptides or flp-11-dependent PHC involvement in the regulation of as yet unknown male-specific behaviors.

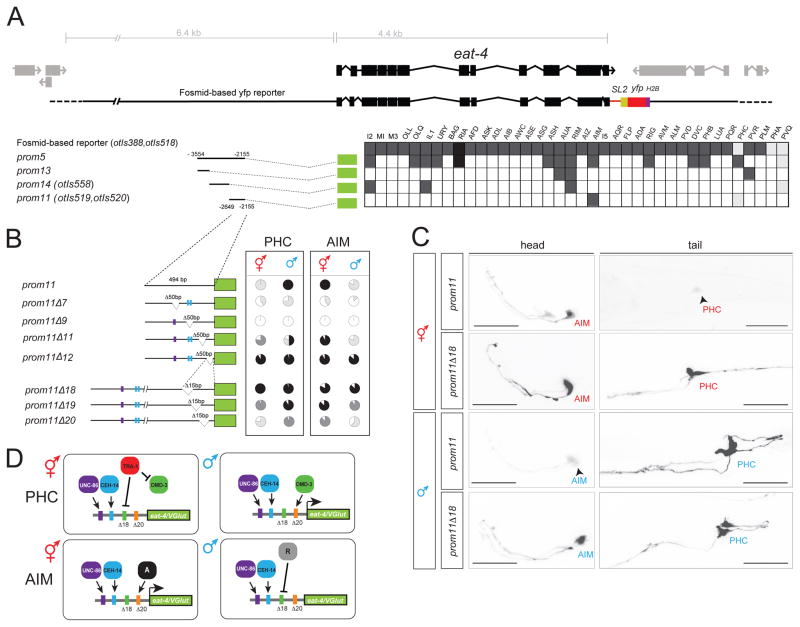

The eat-4/VGLUT locus contains cis-regulatory modules that confer sexually dimorphic expression

As a starting point to dissect the mechanistic basis of PHC remodeling, we turned to the eat-4/VGLUT locus and asked how its sex-specific scaling is controlled. The eat-4/VGLUT locus contains modular cis-regulatory elements that drive eat-4/VGLUT expression, and hence glutamatergic identity, in distinct glutamatergic neuron types of the hermaphrodite nervous system [23]. One module (“prom5”) drives expression in PHC as well as multiple other glutamatergic neurons [23](Fig. 5A). We narrowed down this module to a 494bp region (“prom11”) that not only recapitulates the sex-specific scaling of the endogenous eat-4/VGLUT locus in PHC during sexual maturation, but also shows sexually dimorphic expression in a single pair of head interneurons, the AIM neurons (Fig. 5C). In males, these neurons switch their neurotransmitter usage from glutamate (eat-4/VGLUT expression) to acetylcholine [24].

Fig. 5. Analysis of the cis-regulatory control elements of the eat-4 locus.

A: Dissection of the eat-4prom5 promoter. In the analysis of expression between two and three lines (n > 10) were scored for expression. The different shades of gray indicate the relative fluorescence intensity.

B: Deletion analysis of the eat-4prom11 promoter. The pie charts indicate the percentage of neurons that express the array with the four different shades denoting the overall fluorescence intensity in AIM and PHC in both sexes (white: no expression; black: strongest expression observed in any construct; light and dark grey: intermediate levels that are clearly distinct from each other and from maximum or no expression). At least two lines were analyzed for each deletion construct. Color bars in the promoters refer to putative homeodomain binding sites: blue bar indicates the CEH-14 binding site according to the ModEncode consortium; purple bar indicates the putative UNC-86 binding site. See Methods for sequences. See Fig. S1 for effect of CEH-14 and UNC-86 on eat-4 expression.

C: eat-4prom11 and eat-4prom11Δ18 reporter expression in the head and tail of young adults. Scale bar: 25 μm.

D: Summary schematic of eat-4/VGLUT regulatory logic. The same elements are required to achieve activator and repressor effects in the PHC and AIM neurons, but with opposite sexual specificity. In the AIM neurons, unknown factors “A” (for activator) and “R” (for repressor) may be different DMD transcription factors.

How is the expression of this prom11 module controlled? Terminal differentiation of both the AIM and PHC neurons in hermaphrodites requires the LIM homeobox gene ceh-14, the C. elegans ortholog of vertebrate Lhx3/4 and its presumptive partner, the Brn3-like POU homeobox gene unc-86 [23]. ceh-14 and unc-86 not only control eat-4/VGLUT expression in hermaphrodite PHC [24] but are also required for eat-4/VGLUT expression and scaling in males (Fig. S1). Predicted binding sites for UNC-86 and CEH-14 in the eat-4prom11 element are necessary for expression of the prom11 module in both AIM and PHC (Fig. 5B). The authenticity of the CEH-14 binding site is corroborated by the ModEncode consortium, which mapped a CEH-14 binding peak to the location of the prom11 element [25].

To decipher the cis-regulatory logic of sex-specific modulation of eat-4/VGLUT expression in PHC, we further dissected the prom11 module. We expected to either define sex-specific repressor elements that may counteract the non-sex specific activity of unc-86 and ceh-14 (deletion of such repressor elements should result in depression of eat-4prom11 expression in hermaphrodites) or to define sex-specific activator element(s) that may assist unc-86 and ceh-14 to provide sex-specific upregulation of eat-4/VGLUT expression (deletion of such elements should result in a failure to scale reporter gene expression). Through the introduction of deletions in the prom11 module we found evidence for both mechanisms; beside the presumptive UNC-86 and CEH-14 binding sites, we mapped a 15bp repressor element whose deletion resulted in derepression of reporter expression in the PHC neurons of hermaphrodites (prom11Δ18; Fig. 5B,C). The hermaphrodite-specific TRA-1 protein mentioned above, commonly thought to be a repressor protein [26], may act through this cis-regulatory element (however, we could not find any canonical TRA-1 binding site contained in prom11). Notably, the Δ18 deletion in prom11 also results in derepression of reporter gene expression in the AIM head neuron, but with opposite sex-specificity. While the prom11 construct is only expressed in AIM in hermaphrodites, the Δ18 deletion results in derepression in males (Fig. 5B,C).

In addition to the negative regulatory element that prevents the prom11 module from being expressed in hermaphrodite PHC, we also identified an element that is required, in addition to the CEH-14 and UNC-86 sites, for the full extent of eat-4/VGLUT scaling in PHC in males (Fig. 5B,C; Δ20). Like the repressor element Δ18 described above, the Δ20 activator element also has an activating effect in AIM, but again with the opposite sexual specificity since the Δ20 deletion results in a failure to activate reporter gene expression in hermaphrodite AIM (Fig. 5B,C).

In conclusion, these findings suggest that sex-specificity of eat-4/VGLUT scaling in PHC is achieved by combination of (a) non-sex specific activation, (b) specific repression in hermaphrodites (possibly via TRA-1) and (c) sex-specific activation in males (Fig. 5D). A similar activator/repressor logic operates in the AIM neurons, but with opposite sexual specificity (Fig. 5D).

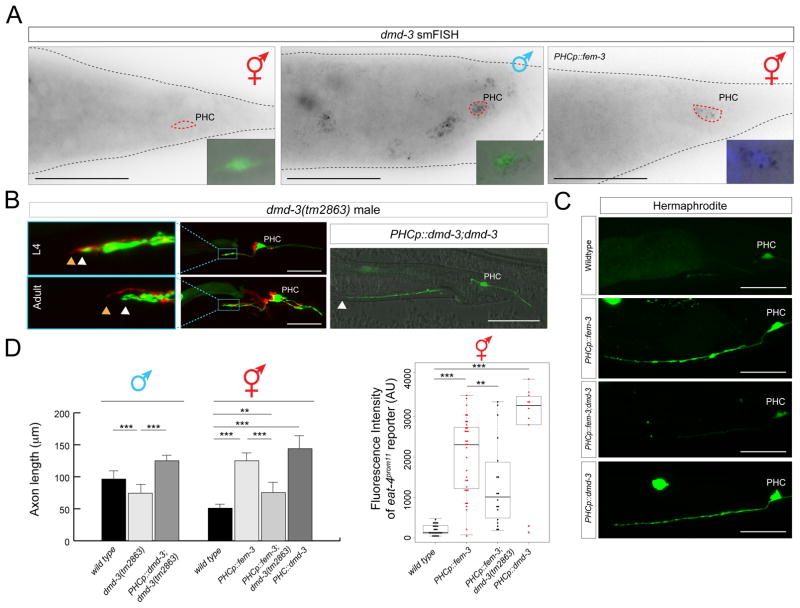

dmd-3 is required and sufficient to cell-autonomously control male-specific PHC differentiation

To identify trans-acting factors that may control the male-specific upregulation of the cis-regulatory module of the eat-4/VGLUT locus mentioned above, we turned to the phylogenetically conserved family of Doublesex/DMRT transcription factors, of which there are 11 homologs encoded in the C. elegans genome. Sexually dimorphic, male-specific functions have been identified for five of these genes so far (mab-3, mab-23, dmd-3, dmd-5, dmd-11)[12, 27]. We analyzed mutants of most dmd genes and found that loss of dmd-3 results in a failure to scale eat-4/VGLUT expression in PHC (Fig. 3B,D). This effect matches the Δ20 deletion within the prom11 module, suggesting that DMD-3 may act directly or indirectly through this module.

We next tested whether the activity of dmd-3 is restricted to scaling eat-4/VGLUT expression, or whether dmd-3 may be a “master regulator” of all PHC remodeling events that we described above. We find that in dmd-3 mutants, the male-specific axon extension of PHC neurons fails to occur (Fig. 2B, Fig. 6B). Moreover, expression of the FMRFamides encoded by the flp-11 locus does not become induced in PHC during sexual maturation of the male (Fig. 4A). We conclude that dmd-3 affects all currently measurable aspects of male-specific PHC differentiation.

Fig. 6. dmd-3 expression and function.

A: smFISH analysis of endogenous dmd-3 expression in young adult animals. No expression is observed in hermaphrodites; in males, expression is observed in multiple cells including PHC, marked with the transgenic array otIs520. Masculinization of PHC (via PHCp::fem-3) in otherwise hermaphroditic animals activates dmd-3 transcription. The inset shows the PHC nucleus stained with DAPI. More than 10 animals were scored for presence of dots in each condition and all animals showed similar staining patterns relative to one another. See Fig. S2 for dmd-3 smFISH probe specificity. Scale bar: 50 μm.

B: PHC axons fail to extend in dmd-3(tm2863) mutant males and these defects are rescued by PHC-specific expression of dmd-3 [oExt6908 (eat-4p11Δ11::dmd-3)]. Scale bars: 50 μm. Wildtype and PHCp::fem-3 data showing in this plot is the same as in Fig. 2B for the adult stage. See panel D for quantification.

C: Ectopic expression of dmd-3 in PHC of hermaphrodites is sufficient to scale eat-4/VGLUT expression (4th panel) and dmd-3 is required in hermaphrodites for the axon extension conferred by masculinization of PHC (2nd and 3rd panel). Transgenic array names: otEx6879, otEx6880 (eat-4p11Δ11::fem-3); otEx6908(eat-4p11Δ11::dmd-3). See panel D for quantification.

D: Quantification of the axon extension and eat-4/VGLUT scaling in the different conditions showed in previous panels. Significance was calculated using student t-test, ***P < 0.005, **P < 0.05.

Upon sexual maturation, male tail hypodermis undergoes remodeling to form a copulatory structure and this remodeling requires hypodermally expressed dmd-3 [28–30]. To examine the focus of dmd-3 action, we first examined the previously uncharacterized neuronal expression pattern of dmd-3. Single molecule in situ hybridization demonstrates that dmd-3 is expressed in a sex-specific manner not only in the male hypodermis, as previously reported [29, 30], but also in the PHC neurons. PHC expression is only observed in males, but not hermaphrodites (Fig. 6A). Male-specificity is controlled cell-autonomously by tra-1, because masculinization of PHC using fem-3 expression results in the induction of dmd-3 expression in the PHC of hermaphrodites (Fig. 6A). This derepression is functionally relevant, since both the axon extension and eat-4/VGLUT scaling observed in transgenic hermaphrodites in which we masculinized PHC via fem-3 expression requires dmd-3 (Fig. 6C,D).

To corroborate that dmd-3 acts in PHC, we generated transgenic animals in which dmd-3 is expressed under control of the PHC (and AIM)-specific fragment of the eat-4/VGLUT locus. This construct rescues the axon extension defect of the PHC neurons in dmd-3 mutant males (Fig. 6B) as well as the eat-4/VGLUT scaling defects of dmd-3 mutants (Fig. 6D). Since the rescuing driver is active in both sexes, we could also assess whether ectopic expression of dmd-3 in hermaphrodites is sufficient for axon extension of PHC and scaling of eat-4/VGLUT expression in a hermaphrodite. We indeed find that dmd-3 is sufficient to induce these PHC features in hermaphrodites (Fig. 6C,D). We conclude that dmd-3 is both required and sufficient to autonomously specify the male-specific identity differentiation program of PHC and that its sex-specificity is controlled by sex-specific repression via TRA-1.

DISCUSSION

While sexually dimorphic neuronal projection patterns have been observed in many different species from flies to humans [3, 4, 31], the simplicity and well-described nature of the C. elegans nervous system reveals neuronal sexual dimorphisms with unrivaled anatomical, cellular and molecular resolution. The case of the PHC neurons particularly stands out because among sex-shared neurons, PHC displays the largest extent of sexually dimorphic connectivity [8]. Other sensory neurons, like PHA or PHB, also switch synaptic partners between the different sexes [8], but they do not differentiate into a densely connected hub neuron as PHC does. Differentiation into a sex-specific hub neuron is not only characterized by changes of en passant synaptic target choices, but apparently requires the coordination of a multitude of anatomical and molecular processes. These include the sex-specific extension of the PHC axon, changes in neuropeptide usage and a transcriptional scaling phenomenon that affects the synaptic vesicle machinery. Cellular differentiation is often accompanied by the scaling of specific subcellular structures and their molecular components in order to adapt to the specialized needs of a cell [32], but such scaling phenomena have not previously been described in the context of the synaptic vesicle machinery. To the contrary, the expression levels of synaptic vesicle components are particularly resilient to genetic perturbations, a robustness that is ensured by their control through multiple redundant cis-regulatory elements [33].

Two remarkable aspects of the sex-specific differentiation process of PHC into a hub neuron are (a) its cellular autonomy and hence independence from other cellular network components and (b) the apparent coordination of different aspects of this sex-specific differentiation process by a single transcription factor, dmd-3. dmd-3 is required and sufficient to trigger the male-specific program of this neuron, including the scaling of the synaptic machinery. dmd-3 operates in a highly context-dependent manner. As previously shown, dmd-3 is required in skin cells for their remodeling during male tail morphogenesis [29, 30], in male-specific cholinergic ray neurons for their differentiation [34] and, as we have shown here, is independently required in a sex-shared neuron to remodel specific anatomical and molecular features. The specificity of action of dmd-3 is determined by cell type-specific combinations of cofactors. In the case of the hypodermis and male-specific cholinergic neurons, DMD-3 interacts with another DMD factor (MAB-23)[29, 34], while in PHC dmd-3 cooperates with the unc-86 and ceh-14 homeobox genes. For dmd-3 to exert its effect on eat-4/VGLUT scaling, unc-86 and ceh-14 are required as permissive co-factors. One unanticipated conclusion from the cis-regulatory analysis of the synaptic scaling process is that the sex-specificity of this transcriptional regulatory phenomenon is not merely assured by one sex-specific regulatory factor that operates in one sex to either activate or repress a specific gene (Fig. 5D). Rather, sex-specific eat-4/VGLUT expression requires sex-specific repression in one sex (mediated by a specific cis-regulatory element that may be directly or indirectly controlled by TRA-1) and sex-specific activation in the opposite sex (mediated by a specific cis-regulatory element that may be directly or indirectly controlled by DMD-3).

The C. elegans genome encodes eleven predicted DM domain proteins, most of them uncharacterized. We hypothesize that these DM proteins may also intersect with other non-sex-specific differentiation programs to control sex-specific features in the nervous system, such as dimorphisms in synaptic wiring or the hermaphrodite-specific neurotransmitter switch of the AIM interneurons (Fig. 5D). Vertebrate genomes also encode multiple DM domain proteins [27] but their function in sexually dimorphic brain development awaits characterization. In the context of gonad development, DM domain proteins represent the only unifying theme of the otherwise very divergent regulatory mechanisms of sex determination and sexual differentiation throughout the animal kingdom [27].

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Transgenes and DNA

A list of transgenes and information on DNA constructs used to generate transgenic lines can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Male mating assay

Mating assays were done as described previously [12, 13, 35]. Early L4-stage males were transferred to a fresh plates and kept apart from hermaphrodites until they reach sexual maturation (24 hours). Single virgin males were assayed for their mating behavior in the presence of 10–15 adult unc-31(e928) hermaphrodites on a plate covered with a thin fresh OP50 lawn. unc-31 hermaphrodites move very little, allowing for an easy recording of male behavior. Mating behavior was scored within a 15 min time window or until the male ejaculated, whichever occurred first. Males were tested for their ability to locate vulva in a mating assay, calculated as location efficiency (L.E.)[36]. The number of passes or hesitations at the vulva until the male first stops at the vulva were counted. Location Efficiency = 1 / # encounters to stop. PHCp::HisCl1 transgenic animals were transferred to NGM plates containing 10mM histamine a day prior to the mating assay [10, 12].

Harsh touch assay

Harsh touch assays were done as previously described [37]. L4 animals were separated by sex and transferred to either NGM plates or NGM plates containing 10mM histamine (both seeded with OP50) and allowed to mature to adulthood (24 hours). For the assay, adults were transferred to NGM or NGM plus histamine plates seeded with a thin fresh OP50 lawn. Harsh touch stimulus was administered to the anus of the worm using a platinum wire pick while the worm was stationary. An animal that initiated abrupt forward locomotion in response to harsh touch was considered “responding.” Each animal was only assayed one time.

Single molecule FISH

smFISH was done as previously described [38]. Young adult animals were incubated over night at 37°C during the hybridization step. dmd-3 and eat-4 probes were designed by using the Stellaris RNA FISH probe designer and were obtained already conjugated with Quasar 670 and purified from Biosearch Technologies. Both probes were used at a final concentration of 0.25 μM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Qi Chen for generating transgenic strains and member of the Hobert lab for comments on the manuscript. Strains were provided by the CGC. This work was supported by the NIH (2R37NS039996) and the HHMI. M.O. received postdoctoral fellowship support from the EMBL and the HFSPO. E.A.B. received predoctoral fellowship support from the NIH (1F31NS096863-01).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.S.-S. performed all experiments except the behavioral experiments which were performed by M.O.-S. (mating) and E.B. (touch). E.S.-S. and O.H. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Yang CF, Shah NM. Representing sex in the brain, one module at a time. Neuron. 2014;82:261–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto D. Male Fruit Fly’s Courtship and Its Double Control by the Fruitless and Doublesex Genes. In: Gewirtz JC, Kim Y-K, editors. Animal Models of Behavior Genetics. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2016. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu JY, Kanai MI, Demir E, Jefferis GS, Dickson BJ. Cellular organization of the neural circuit that drives Drosophila courtship behavior. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1602–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohl J, Ostrovsky AD, Frechter S, Jefferis GS. A bidirectional circuit switch reroutes pheromone signals in male and female brains. Cell. 2013;155:1610–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cachero S, Ostrovsky AD, Yu JY, Dickson BJ, Jefferis GS. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulston JE, Albertson DG, Thomson JN. The Caenorhabditis elegans male: postembryonic development of nongonadal structures. Dev Biol. 1980;78:542–576. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarrell TA, Wang Y, Bloniarz AE, Brittin CA, Xu M, Thomson JN, Albertson DG, Hall DH, Emmons SW. The connectome of a decision-making neural network. Science. 2012;337:437–444. doi: 10.1126/science.1221762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. Biological Sciences. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pokala N, Liu Q, Gordus A, Bargmann CI. Inducible and titratable silencing of Caenorhabditis elegans neurons in vivo with histamine-gated chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2770–2775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400615111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bargmann CI. WormBook. 2006. Chemosensation in C. elegans; pp. 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oren-Suissa M, Bayer Ea, Hobert O. Sex-specific pruning of neuronal synapses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nature17977. in press (Article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu KS, Sternberg PW. Sensory regulation of male mating behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron. 1995;14:79–89. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall DH, Russell RL. The posterior nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: serial reconstruction of identified neurons and complete pattern of synaptic interactions. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00001.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodgkin J. A genetic analysis of the sex-determining gene, tra-1, in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1987;1:731–745. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.7.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarkower D, Hodgkin J. Molecular analysis of the C. elegans sex-determining gene tra-1: a gene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Cell. 1992;70:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter CP, Wood WB. The tra-1 gene determines sexual phenotype cell-autonomously in C. elegans. Cell. 1990;63:1193–1204. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90415-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schvarzstein M, Spence AM. The C. elegans sex-determining GLI protein TRA-1A is regulated by sex-specific proteolysis. Dev Cell. 2006;11:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starostina NG, Lim JM, Schvarzstein M, Wells L, Spence AM, Kipreos ET. A CUL-2 ubiquitin ligase containing three FEM proteins degrades TRA-1 to regulate C. elegans sex determination. Dev Cell. 2007;13:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehra A, Gaudet J, Heck L, Kuwabara PE, Spence AM. Negative regulation of male development in Caenorhabditis elegans by a protein-protein interaction between TRA-2A and FEM-3. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1453–1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mowrey WR, Bennett JR, Portman DS. Distributed effects of biological sex define sex-typical motor behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2014;34:1579–1591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4352-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Kim K. Neuropeptide Gene Families in Caenorhabditis elegans. In: Geary TG, editor. Neuropeptide Systems as Targets for Parasite and Pest Control. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serrano-Saiz E, Poole RJ, Felton T, Zhang F, de la Cruz ED, Hobert O. Modular Control of Glutamatergic Neuronal Identity in C. elegans by Distinct Homeodomain Proteins. Cell. 2013;155:659–673. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira L, Kratsios P, Serrano-Saiz E, Sheftel H, Mayo AE, Hall DH, White JG, LeBoeuf B, Garcia LR, Alon U, et al. A cellular and regulatory map of the cholinergic nervous system of C. elegans. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu W, Lu ZJ, Zhong M, Sarov M, Murray JI, Brdlik CM, Janette J, Chen C, Alves P, Preston E, et al. Diverse transcription factor binding features revealed by genome-wide ChIP-seq in C. elegans. Genome Res. 2011;21:245–254. doi: 10.1101/gr.114587.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berkseth M, Ikegami K, Arur S, Lieb JD, Zarkower D. TRA-1 ChIP-seq reveals regulators of sexual differentiation and multilevel feedback in nematode sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16033–16038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312087110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matson CK, Zarkower D. Sex and the singular DM domain: insights into sexual regulation, evolution and plasticity. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:163–174. doi: 10.1038/nrg3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen CQ, Hall DH, Yang Y, Fitch DH. Morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans male tail tip. Dev Biol. 1999;207:86–106. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason DA, Rabinowitz JS, Portman DS. dmd-3, a doublesex-related gene regulated by tra-1, governs sex-specific morphogenesis in C. elegans. Development. 2008;135:2373–2382. doi: 10.1242/dev.017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson MD, Zhou E, Kiontke K, Fradin H, Maldonado G, Martin D, Shah K, Fitch DH. A bow-tie genetic architecture for morphogenesis suggested by a genome-wide RNAi screen in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, Satterthwaite TD, Elliott MA, Ruparel K, Hakonarson H, Gur RE, Gur RC, Verma R. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:823–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills JC, Taghert PH. Scaling factors: transcription factors regulating subcellular domains. Bioessays. 2012;34:10–16. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefanakis N, Carrera I, Hobert O. Regulatory Logic of Pan-Neuronal Gene Expression in C. elegans. Neuron. 2015;87:733–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siehr MS, Koo PK, Sherlekar AL, Bian X, Bunkers MR, Miller RM, Portman DS, Lints R. Multiple doublesex-related genes specify critical cell fates in a C. elegans male neural circuit. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia LR, LeBoeuf B, Koo P. Diversity in mating behavior of hermaphroditic and male-female Caenorhabditis nematodes. Genetics. 2007;175:1761–1771. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peden EM, Barr MM. The KLP-6 kinesin is required for male mating behaviors and polycystin localization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2005;15:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Kang L, Piggott BJ, Feng Z, Xu XZ. The neural circuits and sensory channels mediating harsh touch sensation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2011;2:315. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji N, van Oudenaarden A. Single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) of C. elegans worms and embryos. WormBook. 2012:1–16. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.153.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.