Abstract

Objective

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) plays an important role in lipoprotein metabolism; however, whether inhibition of CETP activity can prevent cardiovascular disease remains controversial.

Approach and Results

We generated CETP knockout (KO) rabbits by zinc finger nuclease gene editing and compared their susceptibility to cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis to that of wild-type (WT) rabbits. On a chow diet, KO rabbits showed higher plasma levels of HDL-C than WT controls, and HDL particles of KO rabbits were essentially rich in apoAI and apoE contents. When challenged with a cholesterol-rich diet for 18 weeks, KO rabbits not only had higher HDL-C levels but also lower total cholesterol levels than WT rabbits. Analysis of plasma lipoproteins revealed that reduced plasma total cholesterol in KO rabbits was attributable to decreased apoB-containing particles while HDLs remained higher than that in WT rabbits. Both aortic and coronary atherosclerosis was significantly reduced in KO rabbits compared to WT rabbits. ApoB-depleted plasma isolated from CETP KO rabbits showed significantly higher capacity for cholesterol efflux from macrophages than that from WT rabbits. Furthermore, HDLs isolated from CETP KO rabbits suppressed TNFα-induced VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression in cultured endothelial cells.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence that genetic ablation of CETP activity protects against cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis in rabbits.

It is well-known that high levels of plasma HDL-C are inversely correlated with low risk of cardiovascular disease1. Elevation of plasma HDL-C has been considered as a new strategy for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease2. One of the therapeutic strategies to raise plasma HDL-C is the inhibition of plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)3, 4. CETP is a hydrophobic glycoprotein synthesized mainly in the liver and circulates in blood in association with HDL. CETP transfers cholesteryl esters, triglycerides, and phospholipids among lipoproteins therefore playing an important role in the metabolism of lipoproteins and the reverse cholesterol transport from the peripheral tissues to the liver3. Patients genetically deficient for the CETP gene showed low or no CETP activity along with hyper-HDL-cholesterolemia5, 6. Patients deficient for CETP have a low incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) if their plasma HDL-C levels >80mg/dl7, 8, whereas those carrying CETP mutations such as D442G are found to have low HDL-C and high levels of triglycerides, which are associated with high prevalence of CHD9. In spite of this complexity, inhibition of CETP was considered a promising way to treat cardiovascular disease through elevation plasma HDL-C10. This notion was initially supported by the finding that inhibition of CETP activity by vaccine11, antisense12 or therapeutic inhibitors13–15 in cholesterol-fed rabbits raised plasma HDL-C and attenuated atherosclerosis. Unfortunately, other studies failed to demonstrate atheroprotective effects from inhibiting CETP (either by vaccine or CETP inhibitors) in cholesterol-fed rabbits16, 17. Transgenic expression of the simian CETP gene in mice, a species without endogenous CETP gene, resulted in severe atherosclerosis18. In the meantime, human clinical trials of CETP inhibitors were generally unsuccessful, due to off target side effects (torcetrapib), or lack of efficacy (dalcetrapib and evacetrapib)19–22. Currently, Merck’s anacetrapib is ongoing a Phase III clinical trial, which is expected to be completed by 2017. This conflicting landscape underscores the need for further studies on CETP roles and its value as a therapeutic target. In this study, we generated CETP KO rabbits by Zinc Finger Nuclease (ZFN) mediated gene targeting to clarify the pathophysiological functions of CETP in atherosclerosis. Rabbits are sensitive to cholesterol diet challenge and have been widely used as a classical model system to study hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis23. Importantly, wild type (WT) rabbits have the CETP gene and show high plasma CETP activity. Our current study showed that deletion of the CETP gene in rabbits protects against cholesterol diet-induced atherosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

Generation and characterization of CETP KO rabbits

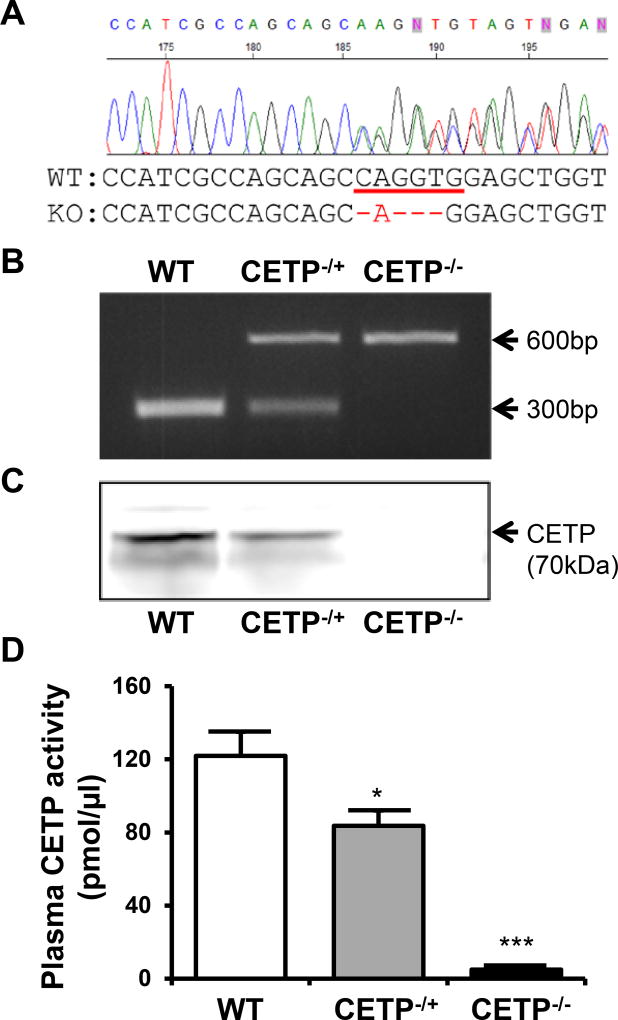

We used three ZFN pairs designed by the SAGE Labs (St. Louis, MO) for rabbit CETP gene targeting. ZFN activity was measured by the yeast MEL-1 assay24. Based on the results, we choose the ZFN pair 1 (ZFN-1) for CETP gene targeting in rabbit embryos. The ZFN-1 target sequence is ctgtccatcgccagcagcCAGGTGgagctggtggacgccaag, and is located in exon 3 of the rabbit CETP gene. ZFN-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) stimulate error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) at specific genomic locations. NHEJ typically leads to the introduction of small insertions or deletions (indels) at the site of the break, often inducing frame-shifts that knockout target gene functions. A total of 188 embryos were injected with ZFN-1 mRNA and transferred to 11 pseudo-pregnant recipient rabbits (16–18 embryos per recipient). After 1-month gestation, six (54.5%) recipients gave birth to 30 live kits (5 kits/Litter), out of which 3 were identified as positive KO founders after an initial T7 endonuclease assay and final confirmation by PCR and sequencing. One founder rabbit had a 4bp deletion that introduced an early stop codon into the CETP gene and this rabbit was used for breeding heterozygous and homozygous KO rabbits (Figure 1A) for this study. Genotyping of the CETP KO hetero- and homozygous rabbits was conducted by PCR and homozygous KO rabbits showed no CETP proteins in the plasma while CETP activity was almost undetectable compared to the WT littermates (Figure 1B–D).

Figure 1. Generation of CETP KO rabbits by ZFN genome editing.

A. Sequencing analysis revealed 4bp deletion that introduces an early stop codon into the CETP gene. The 4 bp deletion also causes the loss of an XcmI restriction enzyme recognition site. B. PCR for the genotyping of rabbits WT, hetero and homozygous for the CETP gene was conducted with the primers caccgccagcaccccgcacacc (Forward) and tcaaccccagaagccccgaggacact (Reverse) which result in a 608bp and 604bp amplicon from WT and homozygous CETP knockout allele, respectively. Subsequent XcmI enzyme digestion brings the WT amplicon to 293 and 315bp, as evidenced by agarose gel electrophoresis. C. Plasma CETP protein was detected by Western blotting using a monoclonal antibody against rabbit CETP. One microliter of plasma was loaded in each lane. D. Plasma CETP activity was measured by Roar CETP activity assay kit as described in the materials and methods. N=8–14 for each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, *** P<0.001 vs. the WT control group.

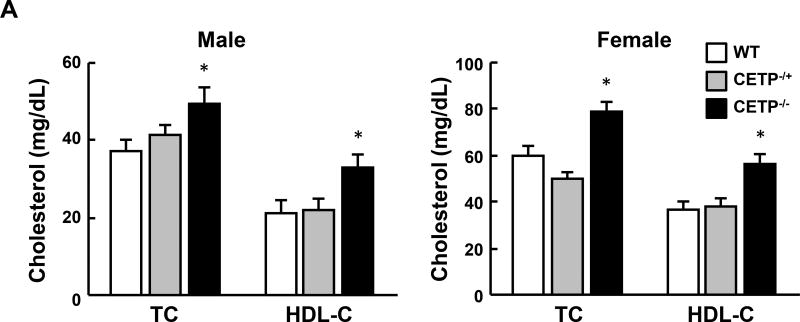

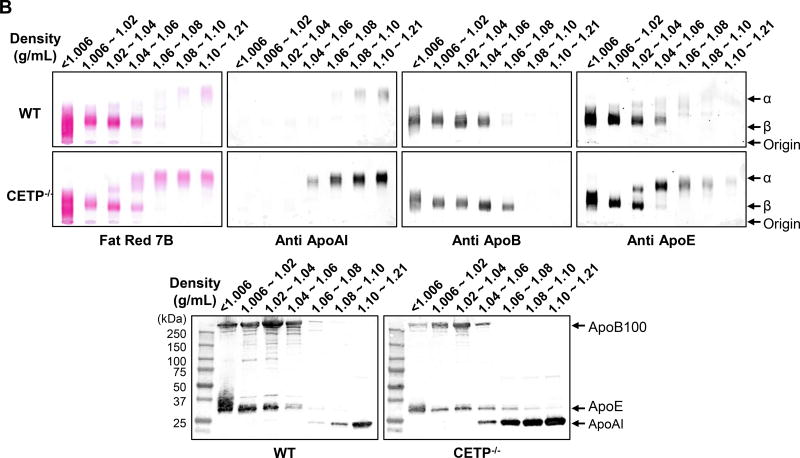

CETP KO rabbits showed no apparent abnormalities in terms of body weight and autopsy examination did not reveal any changes in lung, heart, kidneys, liver and other organs (data not shown). On a chow diet, both male and female homozygous (but not heterozygous) KO rabbits showed significantly higher levels of plasma TC (34% and 32% increase over the control, respectively), which is mainly due to increased HDL-C levels (52% and 54% increase over the control, respectively) (Figure 2A), while TG levels were unchanged (data not shown). Analysis of plasma lipoproteins showed that all HDL particles (HDL1-HDL3, with a density range from 1.04 to 1.21 g/ml) in homozygous KO rabbits were increased along with enrichment of apoAI and apoE contents while apoB-containing particles were unchanged compared with control rabbits (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Analysis of plasma lipid profiles from rabbits fed a chow diet.

A. Total cholesterol (TC) and HDL-C levels in plasma from CETP KO and WT rabbits. B. Plasma lipoproteins of rabbits fed a chow diet. Top panels. Plasma lipoproteins were separated by sequential density ultracentrifugation according to the density ranges shown above the gels. An equal volume of each fraction was resolved by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. Lipoproteins were visualized using Fat red 7B staining, and apolipoproteins were identified by immunoblotting with specific antibodies against apoB, apoE, and apoAI. α and β indicate electrophoretic mobility. Bottom panels. These fractions were further analyzed using 5~20% SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies against apoB, apoE, and apoAI. N=8–14 for each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. All rabbits are in the range between 3 to 4 month old. *P<0.05 vs. the WT control group.

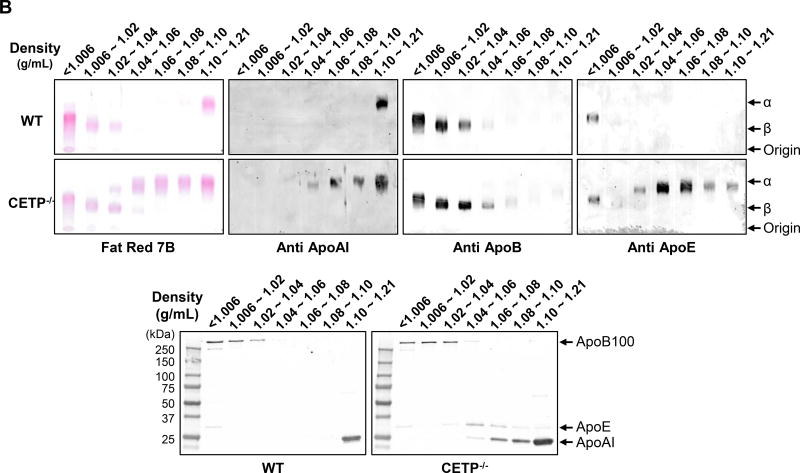

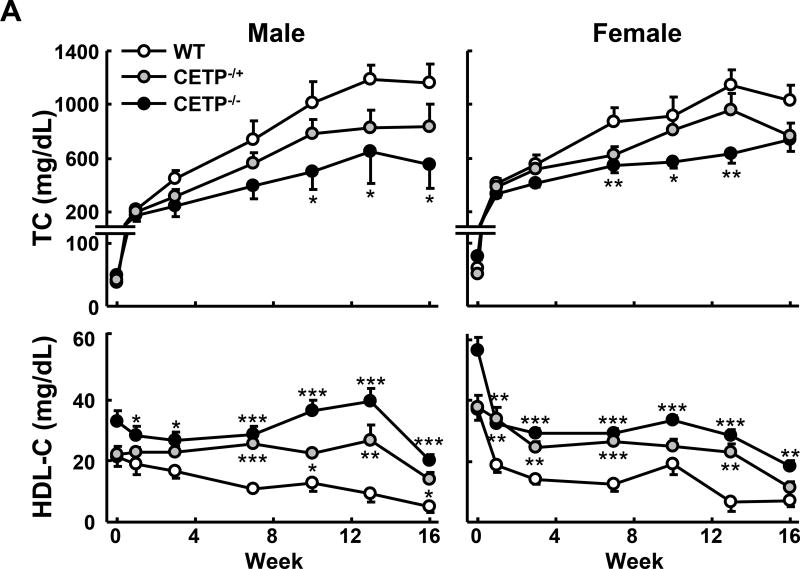

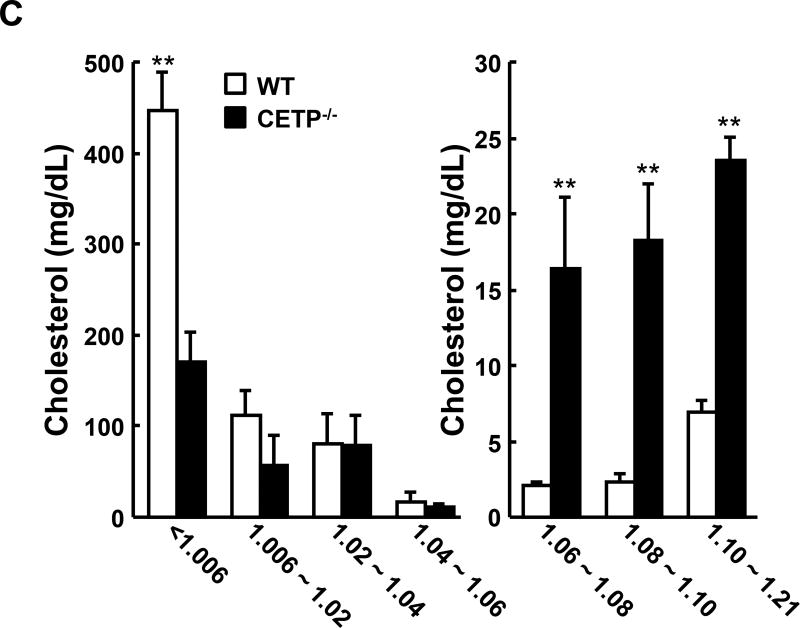

Next we examined the response of CETP KO rabbits to a cholesterol-rich diet (Figure 3). At baseline (Week 0) TC levels were as follows: for the male rabbits, 37±3, 41±3 and 50±4 mg/dL (mean ± SEM) for wild type, heterozygous and homozygous CETP knockout rabbits, respectively; for the female rabbits, they were 60±4, 30±3 and 79±5 mg/dL (mean ± SEM) for wild type, heterozygous and homozygous KO rabbits, respectively. As shown in Figure 3A, both hetero- and homozygous CETP KO rabbits exhibited lower hypercholesterolemia compared with WT rabbits throughout the experimental period. This trend was seen in both male and female rabbits carrying the KO allele but statistical significance was only achieved in homozygous KO rabbits. In spite of this, HDL-C levels in both hetero- and homozygous KO rabbits remained consistently higher than in WT rabbits. On the other hand, cholesterol feeding did not significantly change TG levels and there was no significant difference between KO and WT rabbits (data not shown). Analysis of plasma lipoproteins showed that there were two striking features in cholesterol-fed KO rabbits compared with controls. First, apoB-containing particles (β-VLDL) were remarkably reduced in KO rabbits (Figure 3B–C). Second, HDL1–3 was increased with enrichment of apoAI and apoE in KO rabbits compared to WT rabbits (Figure 3B–C).

Figure 3. Analysis of plasma lipid profiles from rabbits fed a cholesterol-rich diet.

A. The plasma lipid profile was monitored during the 16 weeks of cholesterol-rich diet treatment. N=8–14 for each group. B. Plasma lipoproteins were separated by sequential density ultracentrifugation and analyzed as in figure 2B. C. Cholesterol contents of each lipoprotein fraction were quantified using the Wako total Cholesterol assay kit. The combined recovery for each animal averaged ~80% of the total amount in plasma. N=3 for each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01 or *P<0.05 vs. WT control group.

Quantification of aortic and coronary atherosclerosis

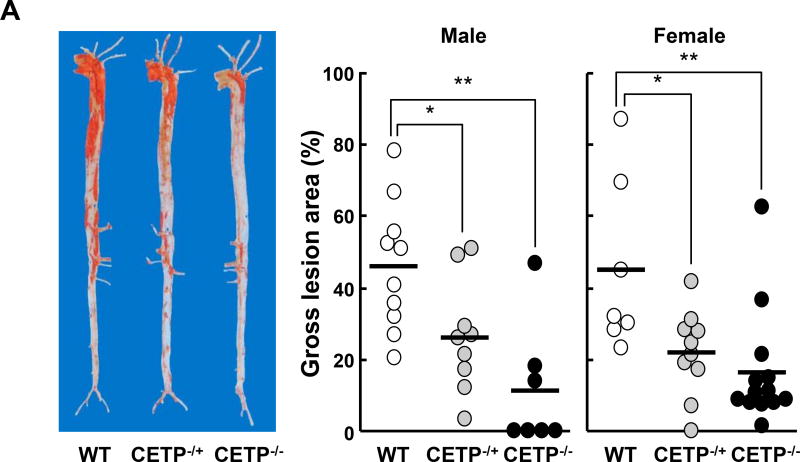

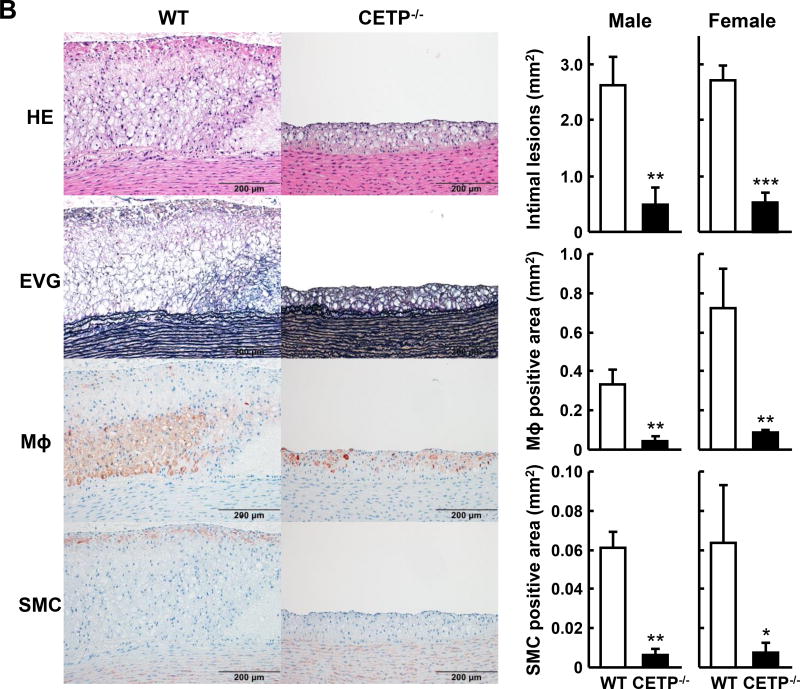

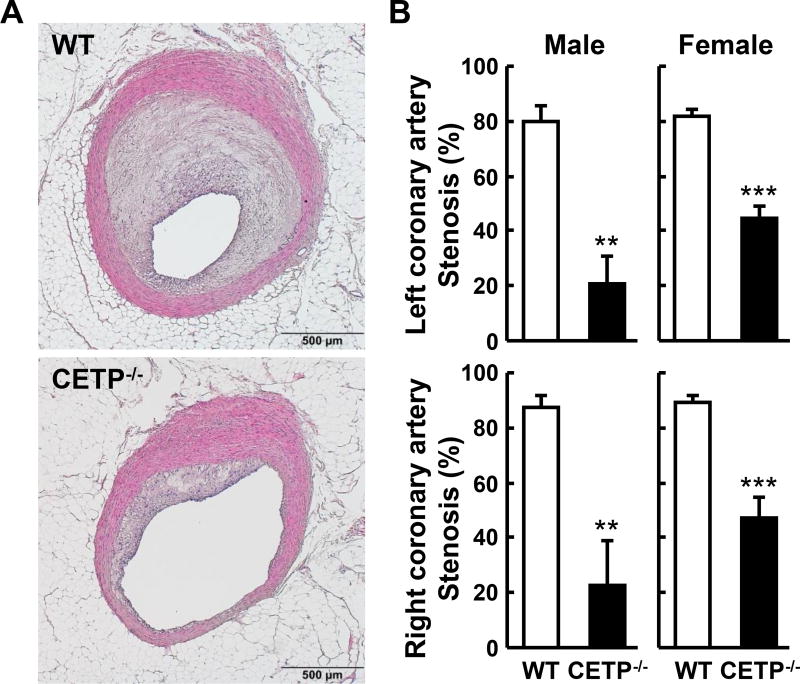

Analysis of en face aortic lesion area revealed that KO rabbits had significantly smaller aortic atherosclerotic lesions than WT rabbits (Figure 4A). In KO males, there was a 43% reduction (p<0.05) in heterozygous and a 75% reduction (p<0.01) in homozygous KO rabbits over the WT controls. In KO females, there was a 52% reduction (p<0.05) in heterozygous and a 64% reduction (p<0.01) in homozygous KO rabbits over the respective WT controls. Microscopic examination of lesions also showed prominent reduction of intimal lesion size with 82% and 81% reduction in male and female homozygous KO rabbits, respectively, compared with WT littermate controls. The aortic lesions of KO rabbits were characterized by reduced macrophage staining by 88% in males and 86% in females over the respective WT controls and smooth muscle cells by 90% in males and 88% in females over the respective WT controls (Figure 4B). We also measured coronary atherosclerosis and found that coronary stenosis was significantly reduced by 74% in male KO rabbits and 47% in female KO rabbits compared with the corresponding WT controls (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 4. Quantification of aortic atherosclerosis at 16 weeks of cholesterol-rich diet feeding.

A. Representative pictures of aortas stained with Sudan IV are shown on the left. The lesion area (defined by sudanophilic staining as red) was quantified using an image analysis system (right). Each dot represents the lesion area of an individual animal. Horizontal bar represents the mean for each genotype. N=7–13 for each group. B. Representative micrographs of the aortic arch lesions from each group. Serial cuts from paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and elastica van Gieson (EVG) or immunohistochemically stained with monoclonal antibodies against macrophages (Mϕ) or α-smooth muscle actin for smooth muscle cells (SMCs). The lesions are characterized by intimal accumulation of macrophage-derived foam cells intermingled with smooth muscle cells (left panels). Scale bars represent 200µm. The right panel shows the quantification of the lesions of different parts of aortas. The intimal lesion area and the area with positive immunostaining for macrophages and SMCs were quantified using an image analysis system as described in the Materials and Methods. N=5–14 for each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01 or *P<0.05 vs. WT control group.

Figure 5. Quantification of coronary atherosclerotic lesions.

A. Representative micrographs of the left coronary atherosclerotic lesions from each group (HE staining). B. The lesion size (expressed as stenosis %) of both right and left coronary arteries is shown. N=5–12 for each group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. **P<0.01 or *P<0.05 vs. WT control group.

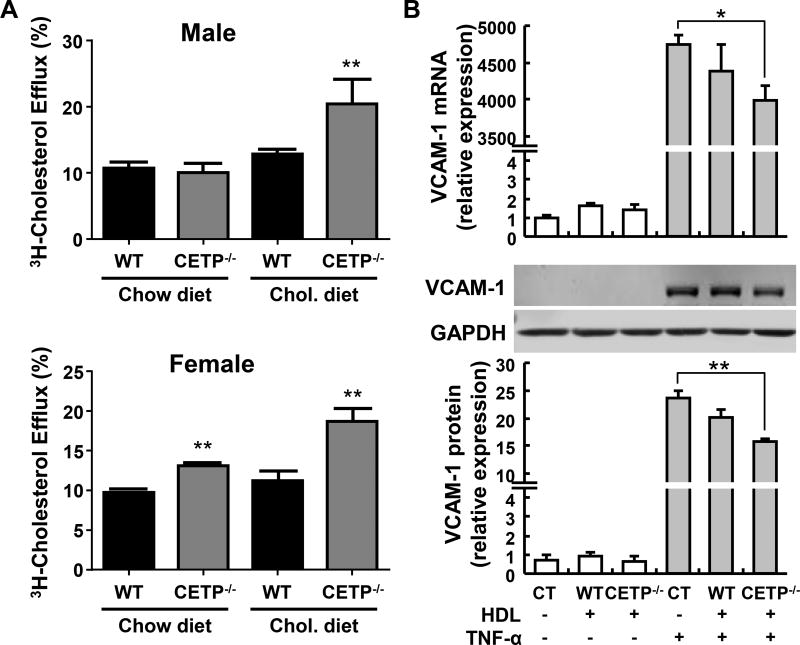

Cholesterol efflux capacity assay

We examined whether there was any functional difference between HDLs of WT and CETP KO rabbits by cholesterol efflux assay. As shown in Figure 6A, apoB-depleted plasma from chow-fed female (but not male) CETP KO rabbits exhibited a significant increase in cholesterol efflux activity. After being fed a cholesterol-rich diet for 10 weeks, we repeated the cholesterol efflux assay and found that ApoB-depleted plasma from both male and female KO rabbits shows significant increase in cholesterol efflux capacity compared to that of the corresponding WT rabbit controls.

Figure 6. Improved HDL function in CETP KO rabbits.

A. Cholesterol efflux capacity assay. A. ApoB depleted plasma from CETP KO rabbits shows significantly higher cholesterol efflux capacity compared with plasma from WT rabbits, especially after cholesterol rich diet feeding. Plasma was collected from male and female rabbits, respectively, fed with normal chow or cholesterol-rich diet for 10 weeks. ApoB-depleted plasma was obtained by PEG precipitation as described in the methods section. B. Anti-inflammatory activity of HDL. HDL3 isolated from CETP KO rabbits shows increased anti-inflammatory in cultured endothelial cells effect than that from WT rabbits. HDL3 was isolated by sequential density ultracentrifugation as described in Figure 2B. HUVECs were pre-treated with rabbit HDL3 (5 µg protein/ml, N=6) for 1hr and then stimulated with TNF-α (1 ng/ml) for 4 h. The expression of the proinflammatory adhesion molecule VCAM-1 was determined by qRT-PCR (upper panel). The protein levels of VCAM-1 were detected by Western blotting (middle and lower panel). Quantitative data were generated with Image Studio (LI-COR) from three independent Western blot experiments. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM *P<0.05 vs. WT group.

Anti-inflammatory effects of HDL

Our finding that CETP KO rabbits had higher HDL levels and those HDLs were enriched in apoAI and apoE, prompted us to examine whether these changes in HDLs affected their anti-inflammatory function. HUVECs were pretreated with HDL3 isolated from either wild type or CETP KO rabbits at the same concentration (5 µg protein/ml) for 1 hour and then stimulated by TNFα for an additional 4 hours. We found that although both HDLs suppressed the expression of VCAM-1 and E-selectin induced by TNFα at both mRNA and protein levels (Figure 6B and Supplemental figure I), the HDLs isolated from CETP KO rabbits showed a tendency to exert stronger inhibitory effects than HDLs isolated from WT rabbits. These findings suggest that an improvement in the anti-inflammatory effect of HDL may also contribute to reduce atherogenesis in CETP KO rabbits.

Discussion

In the current study, we generated CETP KO rabbits by gene editing using a ZFN approach and characterized their lipid and lipoprotein profiles and their susceptibility to cholesterol rich diet-induced atherosclerosis. On a chow diet, and at 4 months of age, only homozygous (but not in heterozygous) KO rabbits showed elevated plasma levels of HDL-C compared with control rabbits. This may suggest that half the amount of CETP protein and activity (as in the heterozygous KO rabbits, Figure 1) is sufficient to maintain plasma HDL-C homeostasis. CETP KO rabbits, with significantly elevated HDL-C, appeared overall healthy and did not show any signs of other abnormalities. It is well known that rabbits develop hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis rapidly when fed a cholesterol-rich diet23. The major lipoproteins in cholesterol-fed rabbits were those of hepatic- and intestinal-derived remnant lipoproteins, called β-VLDLs. β-VLDLs are atherogenic lipoproteins because they are rich in cholesteryl esters (CE) along with apoB-100 and apoE. Both hetero- and homozygous CETP KO rabbits showed lower hypercholesterolemia when compared with WT littermate controls fed a cholesterol-rich diet, suggesting that deficiency of CETP attenuates hypercholesterolemia induced by cholesterol feeding. The molecular mechanisms for this phenomenon remain unknown but it is possible that with lower CETP (as in heterozygous KO rabbits) or absence of CETP activity (as in homozygous KO rabbits) the exchange of CE in HDLs and TG in apoB-containing particles was diminished, thus resulting in less apoB-containing particles or that the apoB-containing particles with less CE could be catabolized faster by the liver. It is not clear whether CETP deficiency has any effects on hepatic LDL receptor activity because hepatic LDL receptor function in cholesterol-fed rabbits is saturated25, 26. In the current study, we did not find significant changes in the expression of LDL receptor and scavenger receptor class B member 1 (SCARB1) in the CETP KO rabbit liver tissue after cholesterol-rich diet feeding for 16 weeks (Supplemental figure II). In a recent report, Miyosawa et al. showed that the CETP inhibitor K-312 mediates LDL cholesterol metabolism by reducing PCSK9 expression15. In human studies, CETP deficiency is associated with low LDL-C levels8 but is insufficient to prevent coronary heart disease in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia because of LDL receptor deficiency27. In addition, CETP inhibitors could also lower the plasma LDL-C in human patients in a recent clinical trial28. Whether this LDL-C lowering effect leads to a reduction of cardiovascular events in humans should be answered in follow up outcome studies.

As predicted, CETP KO rabbits showed significantly higher plasma HDL-C levels than the control rabbits. There is a clear correlation between CETP activity and plasma levels of HDL-C: homozygous KO rabbits >heterozygous KO rabbits >WT rabbits. This finding is consistent with the reports using a CETP vaccine11, antisense12, or inhibitors13–15 in rabbits.

The key question is whether increased HDLs levels in CETP KO rabbits show normal or improved functions. As shown in Figure 6, apoB-depleted plasma isolated from cholesterol-fed CETP KO rabbits exhibited increased cholesterol efflux capacity from cholesterol-loaded macrophages than the plasma from WT rabbits in vitro, which is consistent with CETP inhibitor studies14, 15. Increased HDL particle number in CETP KO rabbits may be responsible for enhancement of cholesterol efflux. In addition, HDL3 isolated from CETP KO rabbits showed potent anti-inflammatory activity. Therefore, increased HDL particles caused by CETP genetic deficiency result in enhancement of HDL functions with no noticeable abnormalities in rabbits.

Both hetero and homozygous CETP KO rabbits are protected against aortic and coronary atherosclerosis compared to WT control rabbits, albeit the reduction in median lesion area was more prominent in homozygous KO rabbits than in heterozygous KO rabbits (even though there was not statistically significance between those two genotypes). Increased resistance to atherosclerosis may result from lower plasma β-VLDL and higher HDL-C levels in the homozygous KO rabbits. It should be noted that the lesions of KO rabbits were characterized by having less macrophages and smooth muscle cells than those of control rabbits. Although CETP deficiency did not affect the specific cell types in the lesions, it is not known whether CETP may have other direct roles in atherosclerotic plaque initiation or progression since lesion macrophages also express CETP29.

In conclusion, we have successfully generated CETP KO rabbits using ZFN genome editing. CETP KO rabbits are protected against cholesterol rich diet-induced atherosclerosis, likely due to lower β-VLDL and higher HDL- levels and functionality. These results support the need for continuing efforts to inhibit CETP for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis and warrant future studies to dissect the roles of CETP in a tissue specific context.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We generated a CETP KO rabbit model by zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) genome editing technology.

CETP KO rabbits show reduced plasma total cholesterol with increased HDL-C levels and functionality compared to wild type rabbits.

Both aortic and coronary atherosclerosis was significantly reduced in CETP KO rabbits compared to wild type controls.

These results indicate that genetic ablation of CETP protects against cholesterol diet-induced atherogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xiancheng Jiang, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, for providing the CETP monoclonal antibody; and Nakagawa Y for her technical assistance in processing pathological specimens.

Sources of funding

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Technology, Japan (22390068, 25670190 and 15H04718 to JF) and NIH grant (R01HL117491 and R01HL129778 to YEC).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ZFN

Zinc finger nuclease

- CETP

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- KO

Knockout

- WT

Wild type

- VLDL

Very low density lipoprotein

- IDL

Intermediate density lipoprotein

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- ApoB

Apolipoprotein B

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Footnotes

Disclosure

None

References

- 1.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High-density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart-disease - framingham study. Am J Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degoma EM, Rader DJ. Novel hdl-directed pharmacotherapeutic strategies. Nature reviews. Cardiology. 2011;8:266–277. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tall AR. Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Journal of lipid research. 1993;34:1255–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barter PJ, Nicholls SJ, Kastelein JJ, Rye KA. Is cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibition an effective strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk? Cetp inhibition as a strategy to reduce cardiovascular risk: The pro case. Circulation. 2015;132:423–432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown ML, Inazu A, Hesler CB, Agellon LB, Mann C, Whitlock ME, Marcel YL, Milne RW, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Takeda R, Tall AR. Molecular basis of lipid transfer protein deficiency in a family with increased high-density lipoproteins. Nature. 1989;342:448–451. doi: 10.1038/342448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita S, Sprecher DL, Sakai N, Matsuzawa Y, Tarui S, Hui DY. Accumulation of apolipoprotein e-rich high density lipoproteins in hyperalphalipoproteinemic human subjects with plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1990;86:688–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI114764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriyama Y, Okamura T, Inazu A, Doi M, Iso H, Mouri Y, Ishikawa Y, Suzuki H, Iida M, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Komachi Y. A low prevalence of coronary heart disease among subjects with increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, including those with plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency. Preventive medicine. 1998;27:659–667. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inazu A, Brown ML, Hesler CB, Agellon LB, Koizumi J, Takata K, Maruhama Y, Mabuchi H, Tall AR. Increased high-density lipoprotein levels caused by a common cholesteryl-ester transfer protein gene mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 1990;323:1234–1238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong S, Sharp DS, Grove JS, Bruce C, Yano K, Curb JD, Tall AR. Increased coronary heart disease in japanese-american men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased hdl levels. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1996;97:2917–2923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barter P. Cetp and atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000;20:2029–2031. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.9.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rittershaus CW, Miller DP, Thomas LJ, Picard MD, Honan CM, Emmett CD, Pettey CL, Adari H, Hammond RA, Beattie DT, Callow AD, Marsh HC, Ryan US. Vaccine-induced antibodies inhibit cetp activity in vivo and reduce aortic lesions in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000;20:2106–2112. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.9.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugano M, Makino N, Sawada S, Otsuka S, Watanabe M, Okamoto H, Kamada M, Mizushima A. Effect of antisense oligonucleotides against cholesteryl ester transfer protein on the development of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:5033–5036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto H, Yonemori F, Wakitani K, Minowa T, Maeda K, Shinkai H. A cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor attenuates atherosclerosis in rabbits. Nature. 2000;406:203–207. doi: 10.1038/35018119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morehouse LA, Sugarman ED, Bourassa PA, Sand TM, Zimetti F, Gao F, Rothblat GH, Milici AJ. Inhibition of cetp activity by torcetrapib reduces susceptibility to diet-induced atherosclerosis in new zealand white rabbits. Journal of lipid research. 2007;48:1263–1272. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600332-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyosawa K, Watanabe Y, Murakami K, Murakami T, Shibata H, Iwashita M, Yamazaki H, Yamazaki K, Ohgiya T, Shibuya K, Mizuno K, Tanabe S, Singh SA, Aikawa M. New cetp inhibitor k-312 reduces pcsk9 expression: A potential effect on ldl cholesterol metabolism. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;309:177–190. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00528.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghebati T, Badiee A, Mohammadpour AH, Afshar M, Jaafari MR, Abnous K, Issazadeh S, Hashemzadeh S, Zareh M, Hashemizadeh H, Nazemi S. Anti-atherosclerosis effect of different doses of cetp vaccine in rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2016;81:468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Z, Inazu A, Nohara A, Higashikata T, Mabuchi H. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor (jtt-705) and the development of atherosclerosis in rabbits with severe hypercholesterolaemia. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:587–594. doi: 10.1042/cs1030587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marotti KR, Castle CK, Boyle TP, Lin AH, Murray RW, Melchior GW. Severe atherosclerosis in transgenic mice expressing simian cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Nature. 1993;364:73–75. doi: 10.1038/364073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barter PJ, Caulfield M, Eriksson M, et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;357:2109–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nissen SE, Tardif JC, Nicholls SJ, Revkin JH, Shear CL, Duggan WT, Ruzyllo W, Bachinsky WB, Lasala GP, Tuzcu EM. Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:1304–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:2089–2099. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLain JH, Alsterda AJ, Arora RR. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors: Trials and tribulations. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1074248416662349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan J, Kitajima S, Watanabe T, Xu J, Zhang J, Liu E, Chen YE. Rabbit models for the study of human atherosclerosis: From pathophysiological mechanisms to translational medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;146:104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyon Y, McCammon JM, Miller JC, Faraji F, Ngo C, Katibah GE, Amora R, Hocking TD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Amacher SL. Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:702–708. doi: 10.1038/nbt1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovanen PT, Brown MS, Basu SK, Bilheimer DW, Goldstein JL. Saturation and suppression of hepatic lipoprotein receptors: A mechanism for the hypercholesterolemia of cholesterol-fed rabbits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78:1396–1400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu G, Salen G, Shefer S, Ness GC, Nguyen LB, Parker TS, Chen TS, Zhao Z, Donnelly TM, Tint GS. Unexpected inhibition of cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase by cholesterol in new zealand white and watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1995;95:1497–1504. doi: 10.1172/JCI117821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haraki T, Inazu A, Yagi K, Kajinami K, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H. Clinical characteristics of double heterozygotes with familial hypercholesterolemia and cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency. Atherosclerosis. 1997;132:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kastelein JJ, Besseling J, Shah S, Bergeron J, Langslet G, Hovingh GK, Al-Saady N, Koeijvoets M, Hunter J, Johnson-Levonas AO, Fable J, Sapre A, Mitchel Y. Anacetrapib as lipid-modifying therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (realize): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;385:2153–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Yamashita S, Hirano K, Nakagawa-Toyama Y, Matsuyama A, Nishida M, Sakai N, Fukasawa M, Arai H, Miyagawa J, Matsuzawa Y. Expression of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in human atherosclerotic lesions and its implication in reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 2001;159:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.