Abstract

It has been shown that real-life implementation studies for the prevention of type 2 diabetes (DM2) performed in different settings and populations can be effective. However, not enough information is available on factors influencing the reach of DM2 prevention programmes. This study examines the predictors of completing an intervention programme targeted at people at high risk of DM2 in Krakow, Poland as part of the DE-PLAN project.

A total of 262 middle-aged people, everyday patients of 9 general practitioners’ (GP) practices, at high risk of DM2 (Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISK) >14) agreed to participate in the lifestyle intervention to prevent DM2. Intervention consisted of 11 lifestyle counseling sessions, organized physical activity sessions followed by motivational phone calls and letters. Measurements were performed at baseline and 1 year after the initiation of the intervention.

Seventy percent of the study participants enrolled completed the core curriculum (n = 184), 22% were men. When compared to noncompleters, completers had a healthier baseline diabetes risk profile (P <.05). People who completed the intervention were less frequently employed versus noncompleters (P = .037), less often had hypertension (P = .043), and more frequently consumed vegetables and fruit daily (P = .055).

In multiple logistic regression model, employment reduced the likelihood of completing the intervention 2 times (odds ratio [OR] 0.45, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.25–0.81). Higher glucose 2 hours after glucose load and hypertension were the independent factors decreasing the chance to participate in the intervention (OR 0.79, 95% 0.69–0.92 and OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.27–0.99, respectively). Daily consumption of vegetables and fruits increased the likelihood of completing the intervention (OR 1.86, 95% 1.01–3.41).

In conclusion, people with healthier behavior and risk profile are more predisposed to complete diabetes prevention interventions. Male, those who work and those with a worse health profile, are less likely to participate and complete interventions. Targeted strategies are needed in real-life diabetes prevention interventions to improve male participation and to reach those who are working as well as people with a higher risk profile.

Keywords: completion the intervention, diabetes type 2, high diabetes risk, lifestyle prevention

1. Introduction

The vivid increase of type 2 diabetes (DM2) prevalence and its complications observed worldwide call for an intensified search for strategies aimed at reducing the disease burden. Lifestyle interventions through dietary and physical changes have proved to be very effective in DM2 prevention and, as demonstrated in several randomized controlled trials (RCTs), they reduce DM2 incidence up to 60%.[1–3] There are also very promising results of real-life implementation studies performed in different settings and populations, which have proved that less-intensive, lower budget lifestyle interventions can also be effective and can result in long-term beneficial outcomes.[4–16]

Nevertheless, there are still many challenges in the field of DM2 prevention. As the main focus is to achieve health benefits at the population level, improvement of the reach and efficacy of the programmes are one of the most important public health burdens. Recruitment rates in RCTs are known to be very low, but this highly controlled clinical situation cannot be compared with real-life setting.[2] However, among randomized patients, completion of the programme was high, which suggests that people participating in RCTs are a very selective, highly motivated group.[2] The data on participation rates and completion of interventions in implementation studies are very scarce. Also, very little is known about the factors affecting completion of intervention and attendance. In some studies, age, education, health, and economic status as well as the level of psychological distress were related to the participation in the programmes.[6,7,11,17,18] There are also very important practical external obstacles like work commitments, accessibility, affordability, and practicality of the interventions, as well as factors related to the quality of intervention provided, which may influence the uptake of the prevention programmes.[17–19] The DE-PLAN project (Diabetes in Europe: Prevention Using Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Nutritional Intervention) was an EU-initiated and sponsored real-life implementation study aiming to assess the reach, adoption, and implementation of the programme in diverse real-life settings in 17 countries in Europe, but also to create a network of trained and experienced professionals to continue DM2 prevention across Europe.[4,5,10,11,20]

The aim of this study was to investigate the predictors of completing an intervention programme within primary healthcare targeted at people at high risk of DM2 in Krakow, Poland within the framework of the DE-PLAN project.

2. Materials and methods

The DE-PLAN project was based on the principles of the Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS)[1] and examined the intervention implementation in real-life settings and hence the design of the study was not randomized.

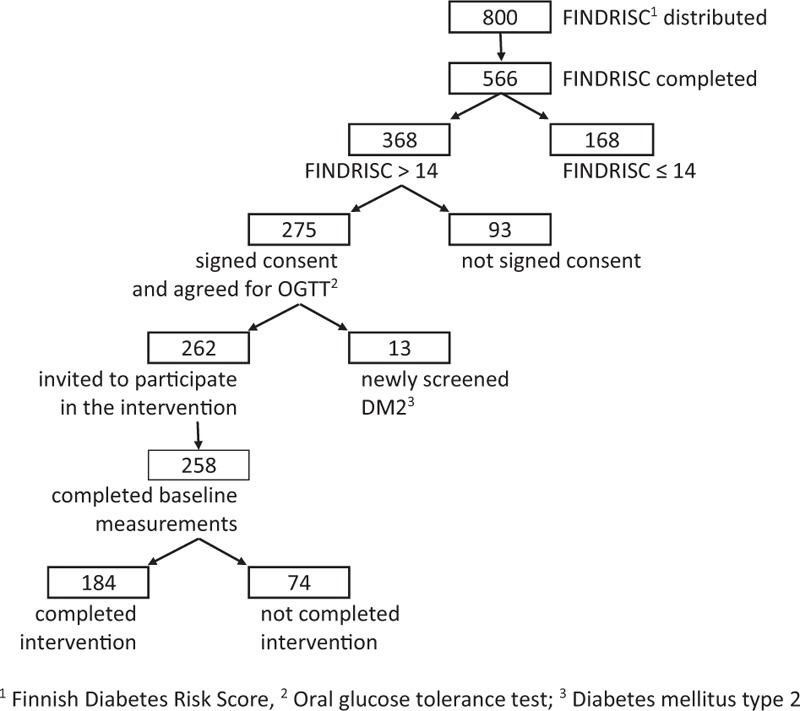

A detailed description of the programme has been published previously.[7,8] The study was performed in 9 independent primary healthcare general practitioners’ (GP) practices in Krakow and entailed city inhabitants aged >25 years who met inclusion criterion of high diabetes risk assessed with the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISK) >14) (33% chance of developing DM2 within 10 years). Information about the study and the leaflets with FINDRISK questionnaire were distributed in co-operating practices. Patients with known risk factors were directly approached by nurses and medical staff. Out of 800 FINDRISK questionnaires distributed, 566 were completed, 368 respondents scored FINDRISK >14 (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

The flow chart: study participants, completers, and noncompleters.

Subsequently, 275 people signed informed consent and agreed to undergo oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) examination. Out of these, 262 (258 with all measurements done) were invited to participate in the intervention. A total 184 participants completed the intervention (completers). Among completers, the number of completed counseling sessions was from 8 to 11 (9 participants completed all sessions but not the final examination after 1 year). Around 74 of eligible participants who completed all baseline examination and agreed to participate in the study did not eventually participate in the intervention (noncompleters). Among noncompleters, the number of completed counseling sessions was from 0 to 3.

This study followed the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. The study protocol was approved by the Jagiellonian University Ethics Committee. The committee's reference number is KBET/43/L/2006. All study participants gave their written informed consent before the participation in the study.

Two nurses in each of the participating practices have been trained to act as diabetes prevention managers and deliver intervention. The intervention consisted of reinforced behavior modification with a special focus on the following lifestyle goals: weight loss of initial body mass, reduced intake of total fat, reduced intake of saturated fat, increased consumption of fiber (from fruit, vegetables, and cereal), and increased physical activity.[1,4,5,20]

The intervention lasted 10 months and consisted of 1 individual session and 10 group sessions (10–14 people) followed by 6 motivational telephone calls and 2 motivational letters.[1,4,5,20] From week 4 of the initiation of the intervention, patients were offered free of charge physical activity sessions 2 times a week. In case of a patient's cancellation or no-show for a scheduled appointment, the staff called the patient to reschedule and provide motivation to continue the study. In case of logistic problems to continue counseling with the initial group, the patient was offered participation in another group (with more convenient location and timetable of sessions). In the course of the intervention, 6 meetings were organized for prevention managers to discuss the problems and share their experience, as well as to allow them to consult any issues concerning physical activity, diet, and motivation techniques. In case of nonparticipation, the nurses were asked to provide the reasons explaining the patients’ decision. Prevention managers could also consult a dietitian and physical activity specialist over the telephone.[4,5]

2.1. Measurements and predictors

The baseline examination procedure included: questionnaires (FINDRISK, baseline, clinical, and lifestyle and quality of life) and biochemical tests such as: fasting and 120′OGTT glucose, serum triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, and total cholesterol. Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) was defined as fasting plasma glucose concentration of 6.1 to 7.0 mmol/L. Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was defined as glucose plasma concentration of 7.80 to 11.0 mmol/L after oral administration of 75 g of glucose (OGTT). Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting glucose concentration of >7.0 mmol/L or glucose concentration of >11.1 mmol/L at 2 hours of OGTT (120′ OGTT).[4,5] Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in light indoor clothes, kg) divided by height squared (m2); waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and iliac crest; diastolic and systolic blood pressures were taken while sitting after 10-minute rest.

Data on education, marital status, employment status, history of increased blood glucose, family history of diabetes, Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISK), smoking status, history of hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, and depression were taken with the of self-reported questionnaire.

Lifestyle was explored with the use of simple self-reported questions on physical activity and consumption of vegetables and fruit. The following questions were asked: “Do you perform at least 30 minutes of physical activity at work and/or during leisure time (including normal daily activity each day)” or “Do you eat fruit or vegetables daily?” Measurements were performed at baseline and then repeated after 1 and after 3 years from the initiation of the intervention.[5]

2.2. Statistical analyses

The descriptive analyses are given as percentages (for categorical variables) and means with standard deviations (for continuous variables). Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous ones were applied to compare the distribution between the potential predictors according to whether the participants completed the intervention or not. Stepwise logistic regression models were used to assess the association between the different predictors and outcome variable. The odds ratios (ORs) and the respective 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. A P-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

The data were analyzed using STATISTICA version 12 (StatSoft, Inc, 2014, www.statsoft.com).

3. Results

Out of 368 respondents eligible to participate in the study (FINDRISK > 14), 275 (75%) agreed to undergo OGTT examination and subsequently 262 (71%) agreed to participate in the study (258 with complete baseline examination). A total of 184 (70% of all who agreed) completed the core curriculum while 74 (30% of all who agreed) did not eventually complete the intervention.

Out of those who agreed to participate in the study, 24% were men, while the percentage of men among completers was 22% and among noncompleters was 30% (ns).

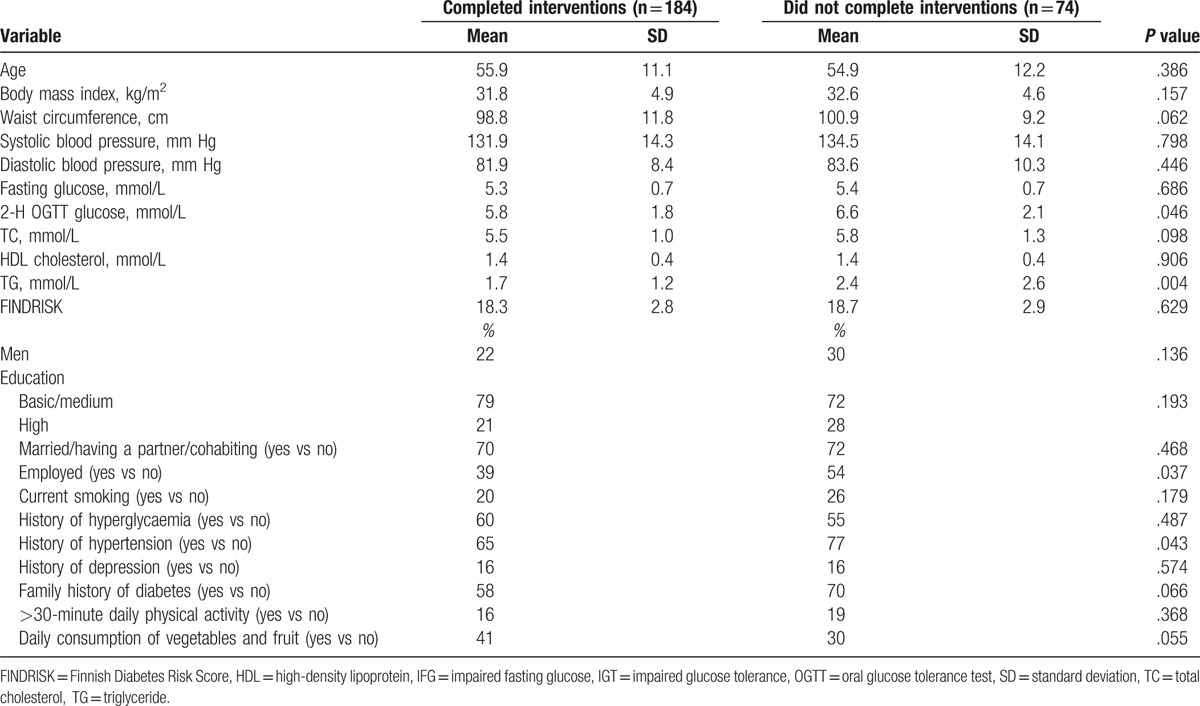

Baseline data of completers and noncompleters are presented in Table 1. Noncompleters had higher 120′ OGTT glucose and triglycerides (P = .046, P = .004) in comparison with completers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of people enrolled in the study according to participation in the intervention.

IFG or IGT was more frequent among noncompleters versus completers (36% vs 25%, P = .069). Those who did not complete the intervention were more frequently employed versus completers (P = .037), more often had a family history of diabetes (P = .066) and hypertension (P = .043). There were no differences in education, marital status, smoking, and frequency of depression between completers and noncompleters. As far as lifestyle factors are concerned, completers more frequently consumed vegetables and fruit every day versus noncompleters (41% versus 30%, P = .055). There were no other baseline differences between completers and noncompleters.

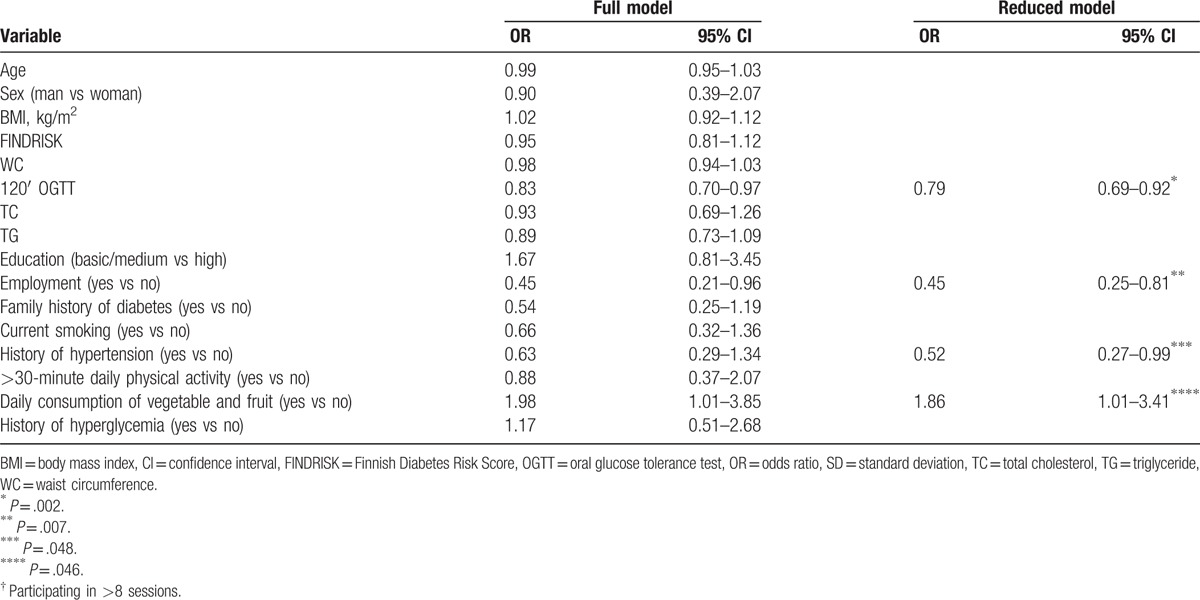

In multiple logistic regression model the status of being employed decreased the likelihood of completing the intervention 2 times (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25–0.81). Patients with higher 120′ OGTT glucose and hypertension were found to have lower completion rate (OR 0.79, 95% 0.69–0.92 and OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.27–0.99, respectively). Daily consumption of vegetables and fruits increased the likelihood of completing the intervention (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.01–3.41) (Table 2). Thirty percent of noncompleters gave the reason of nonparticipation in the intervention, the most commonly declared reasons were: “shortage of time” and “inability to continue time-consuming programme,” “working commitments,” and other commitments like “taking care of children, grandchildren, or elderly parents.”

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of predictors of completing† the lifestyle interventions programme in primary healthcare in Krakow, Poland.

4. Discussion

Results of real-life implementation studies performed in different settings and populations proved that lifestyle DM2 prevention interventions, however less-intensive and less costly than RCTs, can be effective, and that beneficial outcomes can last for a longer time.[7–19] However, in order to achieve health benefits at population level, the reach and efficacy of the programmes should be improved. Therefore, the present study investigates the factors influencing the completion of the DE-PLAN programme designed as a real-life, real-setting, lifestyle DM2 prevention intervention.

In our study, 30% of those who completed all baseline examinations and initially agreed to participate did not eventually complete the intervention. Noncompleters had worse health profile versus completers. People who did not complete the intervention were more frequently employed as compared to completers and more often had hypertension. Completers more frequently consumed vegetables and fruit on a daily basis when compared to noncompleters. Employment was an independent noncompletion factor and it decreased the probability to complete the intervention 2 times. Also, hypertension was an independent factor decreasing the chance to complete the study 2 times, while daily consumption of vegetables and fruit was increasing the chance to complete the study.

In the similar prevention study performed in occupational setting in Finland, out of 657 people (airline employees) with baseline increased DM2 risk invited to the intervention, 53% agreed to participate.[6] Unlike in our study where only 22% of participants were men, in Finland men and women attended the intervention equally. FINDRISK score, waist circumference, BMI, sedentary lifestyle, depression, sleeping problems, and stress affecting work ability increased participation in both sexes.[6] In another DE-PLAN study run in Greece, where patients were recruited through primary healthcare centers and workplace, out of 620 high-risk individuals, 191 agreed to participate in the study and 125 fully completed the programme.[11] In this study, glucose intolerance and the site of recruitment was independently associated with participation in the programme.[11]

In the Sydney Diabetes Prevention Program (Sydney DPP),[18] one-third of eligible patients did not participate in the programme despite undergoing the initial screening process. In this study, people with family history of diabetes and history of high blood glucose, physically inactive were significantly more likely to enroll in the study, while high-risk individuals who smoked, were born in a high diabetes risk region, took blood pressure-lowering medications and consumed little fruit and vegetables were significantly less likely to take up the programme.[18] Low participation in the prevention programmes is observed even among patients with much higher DM2 risk like, for example, in the DM2 prevention trial among women with gestational diabetes.[19] In this study, recruitment was more challenging than anticipated with only 89 out of 410 (22%) women agreeing to participate in the programme.[19] In our study, employment was an independent factor decreasing the likelihood of participation 2 times. This is in concordance with the Health Improvement and Prevention Study (HIPS), where mixed and complex method to assess the factors influencing attendance was used.[17] In this study, people who were older, did not work, and had higher levels of psychological distress were significantly more likely to attend. Working commitments and problems with accessing the programme were described as important obstacles.[17] Attendance was promoted by providing sessions outside working hours. Similarly to our study, in the HIPS, the lifestyle modification programme was taken up mainly by nonworking participants.[17] Also, as reported by Gucciardi et al, conflict with working hours schedule could be the main obstacle in an uptake of DM2 education services.[21] In Finland, in the prevention study among airline company employees, the uptake of the group intervention was so low that group intervention was discontinued.[6] Instead, a diabetes prevention website was created, with good uptake measured as the number of visits per year.[6] In another DPS implementation study run in Finland—FIN-D2D—project with similar uptake of the programme being unemployed and undereducated was related to active participation in the intervention but only in men.[9] In the Greek DE-PLAN study, recruitment through workplace was the most successful strategy in identifying high-risk individuals, enrolling, and maintaining them in the study.[11] Therefore, to improve the reach and attendance of working people it seems essential to develop strategies targeted towards providing convenient and accessible services. In fact, several new strategies are being investigated like for instance internet-based interventions, telephone counseling, mobile apps, or workplace-run interventions.[22–28]

In our study, similarly to the Sydney DPP healthier behaviors like more frequent consumption of vegetables and fruit was observed among completers. In baseline characteristics people who participated in the study also had a better health profile; higher 120′ OGTT glucose was an independent factor decreasing the chance to participate in the intervention. These findings might point out to a higher awareness and motivation among people participating in lifestyle intervention studies and are concordant with previous studies where people participating in epidemiological studies had a healthier profile than general population.[7,8,29,30] This is also in line with some other studies, where participation in the RCTs was high, which suggests that people participating in intervention studies are a very selective and highly motivated group.[2] In our study also people with hypertension were less likely to complete the intervention. This association, also present in the Sydney DPP, is not clear but might be in line with observations that people with a worse health profile are less likely to participate in prevention initiatives.[18]

In our study, there were no particular socioeconomic differences between completers and noncompleters but in previously published research low socioeconomic status was related to less frequent use of health care services despite poorer health status.[30,31] Our findings underline the need of further research to improve the completion of the prevention programmes among high-risk individuals. The lack of association between age and completion of the intervention might result from the narrow age range for this study and small sample size.

Some strengths and limitations of our study need to be discussed. This is one of the first real-life, real-setting studies investigating factors influencing completion of diabetes prevention lifestyle intervention among high diabetes risk individuals without diabetes. The participants in our study were volunteers, and, similarly to many other studies, this one predominantly attracted women. Around 22% out of those who completed the study were men, while among noncompleters the percentage of men was 30%. Very low uptake of the intervention by men suggests that the results of the study might not be generalized to both sexes and implies the need for further studies on sex-specific mechanism of completion of real-life lifestyle interventions. There are also important psychological factors influencing completion and attrition rates in lifestyle prevention programmes which were not studied in our project which further implies the need for continued investigation separately for both sexes.[9,31,32] We should also interpret lifestyle data with caution as the measure of vegetables and fruit consumption frequency and physical activity was very crude.

Furthermore, there are very important practical barriers like work commitments, accessibility, affordability, and practicality of the interventions[17–19] as well as factors related to the quality of intervention given by GPs and prevention officers which were not investigated in our study and, as indicated by other research, might be very important in diabetes prevention programme uptake.[17,18] In our study, some of noncompleters reported also other than working commitments like “taking care of children,” “taking care of grandchildren,” or “taking care of elderly parents” as the reason of the drop out. However, the total number of people who gave any reason of nonparticipation in the intervention was low.

These observations highlight the need to develop lifestyle interventions further in order to increase completion of the programmes by males, particularly those who are working and those at high risk. Results and experience of the DE-PLAN programme were used in the preparation of the European guidelines and the toolkit for the Diabetes Prevention in Europe where some strategies for the reach of focus population have been described.[33,34] The study is being continued in the city of Krakow as a self-government-sponsored initiative.

In conclusion, further insight into the determinants of completion of real-life diabetes type 2 prevention interventions is needed to learn about the barriers as well as to improve the reach and attendance of target population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the nurses—diabetes prevention managers, dietitian, physical activity specialist, and psychologist without whom this work would not have been possible. They are very grateful for the time and expertise they devoted to the performance of the DE-PLAN study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, CVD = cardiovascular disease, DE-PLAN = Diabetes in Europe: Prevention Using Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Nutritional Intervention, DM2 = type 2 diabetes, DPS = Diabetes Prevention Study, FINDRISK = Finnish Diabetes Risk Score, GP = general practitioner, HIPS = the Health Improvement and Prevention Study, IFG = impaired fasting glucose, IGT = impaired glucose tolerance, OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test, RCT = randomized controlled trial, Sydney DPP = Sydney Diabetes Prevention Program.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lindström J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, et al. Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care 2003;26:3230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gilis-Januszewska A, Szybiński Z, Kissimova- Skarbek K, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention in primary health care setting in Poland: Diabetes in Europe Prevention using Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Nutritional Intervention (DE-PLAN) project. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2011;11:1988. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gilis-Januszewska A, Lindström J, Tuomilehto J, et al. Sustained diabetes risk reduction after real life and primary health care setting implementation of the diabetes in Europe prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional intervention (DE-PLAN) project. BMC Public Health 2017;17:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Viitasalo K, Hemiö K, Puttonen S, et al. Prevention of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in occupational health care: feasibility and effectiveness. Prim Care Diabetes 2015;9:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Absetz P, Valve R, Oldenburg B, et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention in the ‘real world’: one-year results of the GOAL Implementation Trial. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Laatikainen T, Dunbar JA, Chapman A, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention in an Australian primary health care setting: Greater Green Triangle (GGT) Diabetes Prevention Project. BMC Public Health 2007;7:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rautio N, Jokelainen F, Oksa H, et al. Participation, socioeconomic status and group or individual counselling intervention in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes: one-year follow-up study of the FIN-D2D-project. Prim Care Diabetes 2012;6:277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Costa B, Barrio F, Cabré JJ, et al. DE-PLAN-CAT Research Group. Delaying progression to type 2 diabetes among high-risk Spanish individuals is feasible in real-life primary healthcare settings using intensive lifestyle intervention. Diabetologia 2012;55:1319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Makrilakis K, Liatis S, Grammatikou S, et al. Implementation and effectiveness of the first community lifestyle intervention programme to prevent Type 2 diabetes in Greece. The DE-PLAN study. Diabet Med 2010;27:459–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vita P, Cardona-Morrell M, Bauman A. Type 2 diabetes prevention in the community: 12-Month outcomes from the Sydney Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016;112:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schwarz PE, Gilis-Januszewska A. Bergman M. Real life diabetes prevention in Europe. Global 378 Health Perspectives in Prediabetes, Diabetes Prevention. Singapore: World Scientific; 2014. 233–57. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yoon U, Kwok LL, Magkidis A. Efficacy of lifestyle interventions in reducing diabetes incidence in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Metabolism 2013;62:303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Johnson M, Jones R, Freeman C, et al. Can diabetes prevention programmes be translated effectively into real-world settings and still deliver improved outcomes? A synthesis of evidence. Diabet Med 2013;30:632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dunkley AJ, Bodicoat DH, Greaves CJ, et al. Diabetes prevention in the real world: effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and of the impact of adherence to guideline recommendations. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2014;37:922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Laws RA, Fanajan M, Javasinghe UW, et al. Factors influencing participation in a vascular disease prevention lifestyle program among participants in a cluster randomized trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Laws RA, Vita P, Venugopal K, et al. Factors influencing participant enrolment in a diabetes prevention program in general practice: lessons from the Sydney diabetes prevention program. BMC Public Health 2012;12:822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Infanti J, O’Dea A, Gibson I, et al. Reasons for participation and non-participation in a diabetes prevention trial among women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). BMC Med Rese Methodol 2014;14:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schwarz PE, Lindström J, Kissimova-Scarbeck K, et al. DE-PLAN project. The European perspective of type 2 diabetes prevention: diabetes in Europe–prevention using lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional intervention (DE-PLAN) project. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2008;116:167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gucciardi E, Demelo M, Offenheim A, et al. Factors contributing to attrition behavior in diabetes self-management programs: A mixed method approach. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eakin E, Reeves M, Lawler S, et al. Telephone counselling for physical activity and diet in primary care patients. Am J Prev Med 2009;26:142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sepah S, Jiang L, Peters AL, et al. Long-term outcomes of a web-based diabetes prevention program: 2-year results of a single-arm longitudinal study. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Neville L, O’Hara B, Milat A. Computer-tailored dietary behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Health Educ Res 2009;24:699–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lawler S, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:419–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Groeneveld I, Proper K, van der Beek A, et al. Lifestyle-focused interventions at the workplace to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease—a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:202–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Weinstein PK. A review of weight loss programs delivered via the Internet. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2007;21:251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Anderson LM, Quinn TA, Glanz K, et al. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:340–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Edelstein SL, Knowler WC, Bain RP, et al. Predictors of progression from impaired glucose tolerance to NIDDM: An analysis of six prospective studies. Diabetes 1997;46:701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lantz PM. Smelser NJ, Baltes PB. Socioeconomic status and health care. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Oxford: Elsevier Science; 2001. 14558–62. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chang M, Niaura R, King T, et al. Depression, smoking, activity level, and health status: pretreatment predictors of attrition in obesity treatment. Addict Behav 1996;21:509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Sardinha LB, et al. A review of psychosocial pre-treatment predictors of weight control. Obes Rev 2005;6:43–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Paulweber B, Valensi P, Lindström J, et al. A European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 2010;42(suppl 1):S3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lindström J, Neumann A, Sheppard KE, et al. Take action to prevent diabetes-the IMAGE toolkit for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Europe. Horm Metab Res 2010;42(suppl 1):S37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]