INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is rising at an alarming rate, affecting 415 million people worldwide and approximately 30 million people in the United States in 2015.1 Approximately half a million patients undergo coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) each year in the United States.2 Nearly 30% to 40% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery have a history of diabetes3,4 and approximately 60% of patients without diabetes develop stress hyperglycemia, defined as a blood glucose greater than 140 mg/dL.5–7

Numerous studies have reported that, in critically ill and cardiac surgery patients, those who develop hyperglycemia are at increased risk for morbidity and mortality.7–16 Perioperative hyperglycemia, in patients with and without diabetes, is associated with higher rates of wound infections, acute renal failure, longer hospital stay, and higher perioperative mortality compared with those without hyperglycemia.8–13 Patients without diabetes who develop stress hyperglycemia during CABG surgery14 or during intensive care unit (ICU) stay15 have worse outcomes compared with those with previous history of diabetes.

Stress hyperglycemia in patients without diabetes undergoing surgery has been associated with up to a 4-fold increase in complications and a 2-fold increase in death compared with patients with normoglycemia16–18 and to subjects with diabetes.16,19–24 Stress mediators, namely stress hormones and cytokines, and the central nervous system interfere with insulin secretion and action leading to increased hepatic glucose production and reduced glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.25,26 The adverse outcomes associated with hyperglycemia may be attributed to hyperglycemia-induced inflammatory and oxidative stress as well as its prothrombotic and vascular abnormalities. This article discusses the pathophysiology of stress-induced hyperglycemia, the impact of hyperglycemia on clinical outcomes, and strategies for the management of hyperglycemia and diabetes in cardiac surgery patients with and without a history of diabetes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF STRESS HYPERGLYCEMIA

Hyperglycemia, defined as a blood glucose level greater than 140 mg/dL, is common in critically ill and cardiac surgery patients, reported in 60% to 80% of cardiac surgery patients5–7 and in and 40% to 60% of general ICU patients.24,27–29 Most critically ill and cardiac surgery patients with hyperglycemia have a previous diagnosis of diabetes.12,24 Most patients with diabetes experience worsening glycemic control due to the stress of surgery and anesthesia or the use of corticosteroids and nutritional support.30 40% to 60% of patients without a history of diabetes experience transient hyperglycemia due to the stress of surgery,31–33 which resolves in many patients at the time of discharge. A third group of patients with inpatient hyperglycemia includes those who are newly diagnosed during hospitalization.33–36 Thus, all patients admitted to the hospital should undergo laboratory glucose testing. Subjects without a history of diabetes with blood glucose greater than 140 mg/dL should have bedside point-of-care glucose testing.37–39 In patients with hyperglycemia, measurement of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) differentiates stress hyperglycemia from diabetes in those who were previously undiagnosed.32,33 The American Diabetes Association and Endocrine Society guidelines indicate that patients with hyperglycemia and an HbA1c of 6.5% or higher can be classified as having diabetes.37 It is important to emphasize, however, that despite a high specificity (100%), the HbA1c cutoff of greater than 6.5% has a poor sensitivity (57%)32 and its use is limited in patients with hemoglobinopathies, recent blood transfusion, severe kidney or liver disease, high-dose of salicylates, pregnancy, and iron deficiency anemia.40 It is important to identify and track patients with stress hyperglycemia, because up to 60% of patients may have confirmed diabetes after 1 year of follow-up.32

REGULATION OF BLOOD GLUCOSE IN HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS AND DURING STRESS

Maintenance of normoglycemia is essential for normal physiology in the body and is maintained by dynamic, minute-to-minute regulation of endogenous glucose production from the liver and kidneys and of glucose utilization by peripheral tissues.25,30,31,41 Glucose production is accomplished by gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Insulin as the main regulatory hormone inhibits hepatic glucose production and stimulates glucose uptake by peripheral tissues (Fig. 1). During prolonged fasting, a reduction in insulin concentration leads to increased lipolysis (fat breakdown) releasing glycerol and to proteolysis (protein breakdown) releasing lactate and amino acids (alanine) that serve as the most important gluconeogenesis precursors.41 Excess glucose is polymerized to glycogen, which is mainly stored in the liver and muscle. Glycogenolysis, mediated primarily by glucagon, breaks down glycogen to the individual glucose units for mobilization during times of metabolic need. These steps are dependent on the interaction between insulin and counter-regulatory hormones.25

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of stress hyperglycemia and its complications in surgical patients.

During stress, the release of counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, and growth hormone) antagonizes the action of insulin, leading to increased gluconeogenesis in the liver and impaired insulin action in peripheral tissues resulting in hyperglycemia. Glucagon excess counteracts the action of insulin on glucose metabolism by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.42 Furthermore, catecholamines stimulate glucagon secretion and inhibit insulin release by pancreatic ß-cells as well as suppression of glucose uptake in peripheral tissues.43 High levels of circulating corticosteroids have been shown to increase gluconeogenesis and lipolysis and to inhibit insulin release.44 Growth hormone increases hepatic glucose production and is known to cause insulin resistance in humans; however, its role during stress is less understood.44

The normal response to stress is associated with activation of central nervous system and neuroendocrine axes with subsequent release of counter-regulatory hormones. These hormones modify the inflammatory response, especially cytokine release that results in several alterations in carbohydrate metabolism, including insulin resistance, increased hepatic glucose production, impaired peripheral glucose utilization, and relative insulin deficiency. Acute stress increases proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1, resulting in increased insulin resistance by interfering with insulin signaling.45 Thus, stress adversely affects multiple biological processes, resulting in diminished insulin action, and if the pancreas is unable to compensate by increasing insulin production, the result is the development of hyperglycemia. Furthermore, in the presence of hyperglycemia, the pancreatic ß-cells develop desensitization (glucose toxicity) that results in further blunting of insulin secretion and increasing serum glucose levels.46

Increasing evidence indicates that development of hyperglycemia leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which affect different biological signaling pathways.47 ROS are formed from the reduction of molecular oxygen or by oxidation of water to yield products, such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical. The mitochondria and NADPH oxidase system are the major sources of ROS production.48 In moderate amounts, ROS are involved in several physiologic processes that produce desired cellular responses. Large quantities of ROS, however, can lead to cellular damage of lipids, membranes, proteins, and DNA. In addition, oxidative stress has also been implicated as a contributor to ß-cell dysfunction and mitochondrial dysfunction, which can lead to the development and worsening of hyperglycemia.49

CONSEQUENCES OF HYPERGLYCEMIA IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

Although the underlying causes have not been completed elucidated, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the higher risk of complications and mortality of hyperglycemia in critically ill patients (see Fig. 1). Severe hyperglycemia causes osmotic diuresis that leads to hypovolemia, decreased glomerular filtration rate, and pre-renal azotemia. Hyperglycemia has been shown to increase rates of hospital infections and to impair collagen synthesis and wound healing among patients with poorly controlled diabetes.25,40,50 It is also associated with impaired leukocyte function, including decreased phagocytosis, impaired bacterial killing, and chemotaxis. In addition, acute hyperglycemia results in nuclear factor kB (NF-κB) activation and production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which cause increased vascular permeability and leukocyte and platelet activation.51 Furthermore, high glucose concentrations have deleterious effects on endothelial function by suppressing formation of nitric oxide and impairing endothelium-dependent flow-mediated dilation as well as abnormalities in hemostasis, including: increased platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation and; reduced plasma fibrinolytic activity.52 Adding to the effects of hyperglycemia in acute coronary syndrome, high free fatty acid levels seen in diabetes and stress can also aggravate ischemia/reperfusion damage by limiting the ability of cardiac muscle to uptake glucose for anaerobic metabolism.25,53

Several studies have shown that the hormonal and proinflammatory aberrations associated with stress hyperglycemia return to normal after treatment with insulin and resolution of hyperglycemia.45 The anti-inflammatory and antihyperglycemic effects of insulin are well established.54,55 Insulin acts to suppress counter-regulatory hormones and proinflammatory transcription factors and may even suppress the formation of reactive oxidation species.56 Insulin suppresses major proinflammatory transcription factors: NF-κB, , activator protein 1, and early growth response 1. Correction of hyperglycemia has been shown to improve the inflammatory response and to reduce generation of ROS (including superoxide radical) generation.56,57 In addition, insulin induces vasodilation and inhibits lipolysis and platelet aggregation. The vasodilation that accompanies insulin administration may be attributed to its ability to stimulate nitric oxide release and induce the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase.58 The impaired lipolysis and reduction in free fatty acids that accompany insulin administration may be associated with decreases in thrombosis and inflammation.53

EVIDENCE FOR CONTROLLING PERIOPERATIVE HYPERGLYCEMIA IN CARDIAC SURGERY PATIENTS

The negative impact of hyperglycemia in patients admitted for cardiac surgery merits a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach. This plan should include dietary modifications, glucose monitoring, personalized glycemic targets to improve hyperglycemia while preventing hypoglycemia, a safe transitioning plan from the ICU to the regular floors and/or home, and proper outpatient follow-up.39,59,60

Intraoperative Period

In a retrospective study of 409 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, Gandhi and colleagues61 reported that for each incremental increase in intraoperative glucose by 20 mg/dL above 100 mg/dL, there was a 30% increase in occurrence of adverse events, including pulmonary and renal complications and death. In contrast to this retrospective study, a randomized controlled trial of 400 diabetic and nondiabetic surgery patients assigned to receive continuous insulin infusion (CII) to maintain intraoperative glucose level between 80 mg/dL and 100 mg/dL versus a glucose target less than 200 mg/dL reported no improvement in clinical outcome or complications.62 A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials in 706 cardiac surgery patients reported that rigorous intraoperative glycemic control decreased the infection rate compared with the conventional therapy but did not decrease mortality.63

Postoperative Period

Several randomized controlled trials in cardiac surgery patients have evaluated the impact of hyperglycemia and ideal blood glucose target during the postoperative period to optimize outcomes.14,64–68 Desai and colleagues64 randomized 189 patients to an intensive target of 90 mg/dL to 120 mg/dL and to a conventional target between 121 mg/dL and 180 mg/dL in first-time CABG surgery patients. They reported no differences in deep sternal wound infection, pneumonia, perioperative renal failure, or mortality. Similarly, Pezzella and colleagues67 and Lazar and colleagues65 reported no differences in perioperative complications, hospital length of stay, and mortality between intensive insulin targeting glucose of 90 mg/dL to 120 mg/dL versus 120 mg/dL to 180 mg/dL. In a recent study, Umpierrez and colleagues14 aimed to determine if the lower end of the recommended glucose target can reduce hospital complications in patients undergoing CABG surgery randomized patients with hyperglycemia to an intensive insulin therapy aimed to maintain a blood glucose between 100 mg/dL and 140 mg/dL or to a conservative therapy aimed to maintain a glucose value between 141 mg/dL and 180 mg/dL in an ICU.14 The primary outcome of this trial was to determine differences between a composite of complications, including wound infection, pneumonia, bacteremia, acute kidney injury, major adverse cardiovascular events, and mortality. The authors found no differences in a composite of complications (42% vs 52%, P = .08).The authors observed, however, heterogeneity in treatment effect according to diabetes status, with no differences in complications among patients with prior history of diabetes treated with intensive or conservative regimens (49% vs 48%, P = .87) but a significantly lower rate of complications in patients without diabetes treated with an intensive treatment regimen compared with the conservative treatment regimen (34% vs 55%, P = .008). In agreement with these findings, a recent study by Blaha and colleagues68 in 2383 cardiac surgery patients treated to a target glucose range between 80 mg/dL and 110 mg/dL reported a reduction in postoperative complications only in nondiabetic patients (21% vs 33%; relative risk, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74), whereas no significant benefit of intensive therapy was seen in patients with diabetes. Moreover, a subgroup analysis by Van den Berghe and colleagues69 of surgical and medical ICU patients reported that whereas glucose lowering effectively reduced mortality in those without a previous history of diabetes, no significant benefit from treatment was observed in patients with diabetes.

Clinical guidelines on inpatient management of hyperglycemia recommend the use of IV CII in critically ill and in cardiac surgery patients with and without a history of diabetes.37,39,60,70,71 Several cohort and randomized controlled trials in cardiac surgery patients have reported that improvement in glycemic control can reduce short-term and long-term complications and hospital mortality.14,68,72,73 A target glucose level between 140 mg/dL and 180 mg/dL is recommended for most ICU and cardiac surgery patients with hyperglycemia and diabetes, but lower targets between 110 mg/dL and 140 mg/dL could be appropriate in a select group of ICU patients (ie, centers with extensive experience and cardiac surgical patients).39 Recent studies in mixed ICU populations and in cardiac surgery patients have shown that intensive insulin therapy (glucose target <110 mg/dL) does not reduce complications compared with conventional control but increases the risk of hypoglycemia.65,74

Table 1 presents a comprehensive review of observational and prospective randomized trials addressing intensive glycemic control in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.14,62,64–68,72,73,75–78 Although the readers should use caution with extrapolating data from the medical or surgical ICUs and combined trials into the cardiothoracic ICU practice, the overall consensus is that hyperglycemia management, targeting less stringent goals (140–180 mg/dL), represents the standard of care in hospitalized patients.38,39,59,60,79

Table 1.

Studies of intensive glycemic control in cardiac surgery populations

| Study | Patients | Population | Target Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furnary et al,76 1999 | N = 2467 | DM | I: 150–200 | 65% reduction in risk of deep sternal wound infections |

| Cardiac surgery | C: >200 | |||

| I: 1499 (CII) | ||||

| C: 968 (subcutaneous) | 85% CABG | |||

|

| ||||

| Van den Berghe et al,72 2001 | N = 1548 | DM and no-DM | I: 80–110 | 32% reduction in adjusted mortality risk |

| I: 544 | 62% cardiac surgery | C: 180–200 | ||

| C: 557 | 57% CABG | |||

| 13% DM | ||||

|

| ||||

| Furnary et al,73 2003 | N = 3554 | DM | Variable: <200 before 1991, 150–200 between 1991–1998, 125–175 between 1999 and 2001 and between 100 and 150 after 2001 | 50% reduction in adjusted mortality risk |

| CABG | ||||

| I: 2612 | ||||

| C: 942 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Lazar et al,66 2004 | N = 141 | DM | I: 125–200 | 60% reduction in postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| CABG | C: <250 | |||

| I: 72 | ||||

| C: 69 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ingels et al,77 2006 | N = 970 | DM and no-DM | I: <110 | 41% reduction in unadjusted mortality risk at 2 y and 22% at 3 y No significant (12.7%) reduction at 4 y |

| Cardiac surgery | C: <220 | |||

| C: 477 | ||||

| I: 493 | <20% DM | |||

|

| ||||

| Li et al,78 2006 | N = 93 | DM | I: 150–200 | No differences in mortality, wound infections, or ICU LOS |

| CABG | C: 150–200 | |||

| C: 42 | ||||

| I: 51 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gandhi et al,62 2007 | N = 371 | DM and no-DM, | I: 80–100 | No significant differences in mortality or morbidity |

| Cardiac surgery | C: <200 | |||

| C: 185 | ||||

| I: 186 | Approximately 20% DM | |||

|

| ||||

| Chan et al,75 2009 | N = 99 | DM and no-DM, | I: 80–130 | No differences in 30-d mortality |

| Cardiac surgery | C: 160–200 | |||

| C: 55 | ||||

| I: 54 | Approximately 30% DM | |||

| Approximately 34% CABG | ||||

|

| ||||

| Lazar et al,65 2011 | N = 82 | DM | I: 90–120 | No differences in 30-d mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, infection, atrial fibrillation, ventilator time, ICU LOS |

| CABG | C: 120–180 | |||

| C: 42 | ||||

| I: 40 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Desai et al,64 2012 | N = 189 | DM and no-DM | I: 90–120 | No differences in deep sternal wound infections, pneumonia, renal failure, or mortality |

| CABG | C: 121–180 | |||

| C: 82 | ||||

| I: 107 | Approximately 41%–45% DM | |||

|

| ||||

| Pezzella et al,67 2014 | N = 189 | DM and no-DM | I: 90–120 | No differences in perioperative complications |

| CABG | C: 121–180 | |||

| C: 98 | No differences in mortality at 40 mo of follow-up | |||

| I: 91 | Approximately 41%–45% DM | |||

|

| ||||

| Blaha et al,68 2015 | N = 2383 | DM and no-DM | I: 80–110 | 37% reduction in risk of postoperative complications in no-DM |

| Cardiac surgery | C: 80–150 | |||

| C: 1134 | No differences in complications in DM | |||

| I: 1249 | Approximately 70% CABG | |||

| Approximately 23%–27% DM | ||||

|

| ||||

| Umpierrez et al,14 2015 | N = 338 | DM and no-DM | I: 100–140 | 62% reduction in risk of postoperative complications in no-DM |

| CABG | C: 141–180 | |||

| C: 151 | No difference in complications in DM | |||

| I: 151 | 50% DM | |||

Abbreviations: BG, blood glucose; C, control/conventional treatment group; DM, diabetes mellitus; I, intervention/intensive treatment group; LOS, length of stay; N, number of patients; no-DM, no history of DM.

MANAGEMENT OF PERIOPERATIVE HYPERGLYCEMIA DURING CARDIAC SURGERY

Management of Hyperglycemia in Intensive Care Unit Settings

Insulin therapy is effective in achieving and maintaining glycemic control in patients with diabetes and with stress hyperglycemia in an ICU.25,38,39,60 Several protocols have been published, both nursing-driven and computer-generated algorithms, which have been validated for their safety and efficacy.80–82

There is no ideal protocol for the management of hyperglycemia in the critical patient. In addition, there is no clear evidence demonstrating the benefit of one protocol/algorithm versus another. Most institutions have standard nursing-driven protocols to facilitate insulin titration and to avoid errors in insulin dosing. Essential elements that increase protocol success are (1) rate adjustment that considers the current and previous glucose values and the current rate of insulin infusion, (2) rate adjustment that considers the rate of change (or lack of change) from the previous reading, and (3) frequent glucose monitoring (hourly until stable glycemia is established and then every 2–3 hours). Several computer-based algorithms aiming at directing the nursing staff adjusting insulin infusion rate have become commercially available (Glucommander [Glytec, Greenville, South Carolina], EndoTool System [MD Scientific, Charlotte, North Carolina], GlucoStabilizer [Medical Decision Network, Charlottesville, Virginia], and GlucoTab [Joanneum Research, Graz, Austria, and Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria]).83 These devices may be especially useful in hospitals with no diabetes management teams or diabetes experts on staff; however, some come at a considerable financial cost to institutions. Table 2 shows an example of the authors’ paper-based IV insulin infusion and hypoglycemia protocol. This protocol was specifically developed to be used in cardiac surgery ICU patients in the authors’ hospitals.

Table 2.

Emory healthcare protocol for intravenous insulin infusion in critically ill patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery with hyperglycemia

| Initiating the insulin drip | |||

| History of diabetes or HbA1c >6.5%: begin insulin drip with first BG >180 mg/dL | |||

| No history of diabetes and HbA1c <6.5%: begin if BG >180 mg/dL × 2 consecutive occasions | |||

|

| |||

| Calculating initial IV insulin infusion rate | |||

| BG/100 = U/h (round to the nearest 0.1; U/h = mL/h) | |||

|

| |||

| Target range: 110–140 mg/dL | |||

|

| |||

| Adjusting the insulin drip | |||

|

| |||

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Any increase in blood glucose from prior blood glucose | Blood glucose decrease less than 30 mg/dL from prior blood glucose | Blood glucose decrease greater than 30 mg/dL from prior blood glucose |

|

| |||

| >241 | Increase rate by 3 U/h | Increase rate by 3 U/h | No change |

|

| |||

| 211–240 | Increase rate by 2 U/h | Increase rate by 2 U/h | No change |

|

| |||

| 181–210 | Increase rate by 1 U/h | Increase rate by 1 U/h | No change |

|

| |||

| 141–180 | Increase rate by 0.5 U/h | Increase rate by 0.5 U/h | No change |

|

| |||

| 110–140 | No change | No change | Decrease rate by 50% |

|

| |||

| 91–109 | Decrease rate by 50% | Decrease rate by 50% |

|

|

| |||

| 71–90 |

|

||

|

| |||

| 70 or less |

|

||

It has been shown that glucose targets are usually achieved with most protocols within approximately 4 hours.84 The onset of regular insulin after IV administration is within 15 minutes to 30 minutes, with a half-life of approximately 9 minutes and duration of action between 30 minutes and 60 minutes. These features allow a rapid up-titration or down-titration of insulin rate in anticipated (ie, rapid decline of blood glucose and use of vasopressors) or unanticipated (ie, acute clinical status deteriorations and hypoglycemia) situations.60,81,82 Insulin infusion requirements are usually higher during the first few hours of infusion in patients with severe hyperglycemia. Postoperative stress, pain, presence of infection or administration of pressors are factors that have an impact on on insulin requirements.82 Thus, it is recommended to monitor glucose values every 1 hours to 2 hours and to adjust insulin infusion rates accordingly.85 Insulin infusion should be continued until clinical and hemodynamic stability has been achieved, until patients are tolerating oral intake or receiving nutritional support, and after several hours of stable glycemic control.

Management of Hyperglycemia in Non-intensive Care Unit Settings

Subcutaneous insulin is the preferred therapeutic agent for glucose control in cardiac surgery patients after stopping CII or after transition to non-ICU areas. Transition to subcutaneous insulin should be considered in hemodynamically stable patients who are off pressors and are tolerating oral intake.82 Use of protocols for insulin transition leads to better glucose control than nonprotocol therapy, with lower rates of complications and hypoglycemia. A protocol-based transition to a subcutaneous regimen, using basal insulin early after initiation of CII, has also been shown to decrease rebound hyperglycemia after infusion discontinuation.86

The basal-bolus (or basal-prandial) insulin regimen is considered the physiologic approach because it addresses the 3 components of insulin requirement: basal (required in the fasting state), nutritional (required for peripheral glucose disposal following a meal), and supplemental (required for unexpected glucose elevations or for disposal of glucose in hyperglycemia).37,39,60 In insulin-naïve patients, the calculation of basal and bolus insulin dosing requirements should be based on a patient’s previous rate of IV insulin infusion and carbohydrate intake.82,85 Due to the short IV insulin half-life, administration of the initial subcutaneous basal dose is recommended at least 2 hours to 4 hours before stopping the insulin infusion to prevent rebound hyperglycemia.

Most nondiabetic patients with stress hyperglycemia requiring less than 1 U/h to 2 U/h frequently do not require transition to scheduled subcutaneous basal-bolus therapy but rather just correctional insulin scale. Those requiring insulin infusion at a rate of greater than 2 U/h can be started to at 50% of the calculated 24-hour insulin requirements. Most patients with a history of diabetes, however, require transition to subcutaneous insulin therapy. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus can be started at 80% of the calculated daily IV insulin requirements.87–89 The total insulin dose is given 50% as basal and 50% as bolus (prandial) insulin.82,85,90–92

Several randomized controlled trials using subcutaneous basal or basal-bolus insulin regimens have been shown successful and are preferred over the use of sliding-scale insulin alone in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.93–95 Basal insulin analogs, such as glargine and detemir, are generally preferred over NPH insulin or premixed insulin, because the latter has been associated with lower glycemic variability and less severe hypoglycemia.96,97 Recently, a study comparing the 2 most commonly used basal insulins, glargine and detemir, in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia and diabetes reported similar efficacy in glycemic control and hypoglycemia rates between these 2 insulin formulations.98 Renal dysfunction, a common complication in hospitalized patients, increases the risk of insulin and non–insulin-related hypoglycemia.99 Baldwin and colleagues100 studied 2 basal-bolus (glargine-glulisine) insulin-dosing regimens in hospitalized patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min). The investigators found that a weight-based insulin regimen of 0.25 U/kg/d was associated with 50% less hypoglycemia (15.8% vs 30%, P = .08) compared with a traditional approach of a total daily dose of 0.5 U/kg. In patients with reduced oral intake, the administration of a single dose of basal once-daily dose plus correctional premeal doses of rapid-acting insulin per sliding scale (basal-plus approach) may be an alternative to basal-bolus regimen.101

GLUCOSE MONITORING DURING THE PERIOPERATIVE PERIOD

All patients with a diagnosis of diabetes and those with newly discovered hyperglycemia should be monitor closely during the perioperative period. The frequency of monitoring and the schedule of the blood glucose checks are dependent on the nutritional intake, patient treatment, and schedule of insulin. Current guidelines recommend glucose monitoring every 1 hour to 2 hours in critically ill patients receiving IV insulin administration.60 There is some controversy regarding the best method to monitor blood glucose. A recent international consensus meeting recommended against relying solely on the use of capillary blood glucose, given the poor reliability of meters in critically ill patients.102 In patients with permanent vascular access (arterial and/or venous), samples for glucose monitoring could be easily drawn after standard safety precautions. Arterial catheters may be preferred in patients with shock, severe peripheral edema, and/or on vasopressor therapy.102 Considering the convenience and wide availability, however, capillary point-of-care testing is the most widely used approach in the hospital setting. When using point-of-care testing, clinicians should account for conditions that might alter the meter accuracy of glucose measurement, such as hemoglobin level, perfusion, and medications. In addition, safety standards should be established for blood glucose monitoring that prohibits the sharing of finger-stick lancing devices, lancets, and needles.30

The use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has been proposed as an alternative to capillary glucose testing in the hospital setting.103–107 CGM provides frequent measurements of glucose levels as well as direction and magnitude of glucose trends facilitating short and long-term therapy adjustments and limiting glycemic excursions. CGM devices can sample glucose intravascularly (venous or arterial blood) or subcutaneously by way of interstitial fluid.104 CGM devices can be highly invasive (intravascular devices), minimally invasive (subcutaneous), or even noninvasive (transdermal). Sampling and measurement frequencies typically range from 1 minute to 15 minutes, but most commonly are done every 5 minutes. There are currently 5 CGMs approved for use in Europe and 1 CGM system approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in US hospitals.104 Although the use of CGM in the ICU population has the potential for improving glucose control from an accuracy standpoint, there are several concerns. Technological limitations that impede accuracy of CGMs include buildup of tissue deposits (biofilm), the need for regular calibration due to sensor drift, measurement lag, and substance interference (acetaminophen, maltose, ascorbic acid, dopamine, mannitol, heparin, uric acid, and salicylic acid). In addition, the intravascular CGM devices carry the risk of thrombus formation, catheter occlusion, and catheter-related infections.108

HYPOGLYCEMIA AND OUTCOMES IN PATIENTS HOSPITALIZED WITH CARDIAC CONDITIONS

Hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) is the most common adverse event associated with insulin administration99,109–111 and has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and higher mortality.74,112 Hypoglycemia is associated with increased risk of arrhythmias, ranging from bradycardia to ventricular ectopic beats and QT prolongation, mostly because of sympathetic and adrenal activation.113 The relationship between mortality and glycemic control in hospitalized patients with acute cardiovascular disease follows a U-shape curve,114–116 with a 2-fold increase in mortality in patients with hypoglycemia.74 In the NICE-SUGAR (The Normoglycemia in Intensive Care Evaluation–Survival Using Glucose Algorithm Regulation) trial, the adjusted hazard ratios for death among patients with moderate (<70 mg/dL) or severe (<40 mg/dL) hypoglycemia, compared with those without hypoglycemia, were 1.41 (95% CI, 1.21–1.62; P<.001) and 2.10 (95% CI, 1.59–2.77; P<.001), respectively. Several studies have reported that spontaneous hypoglycemia is associated with worse outcomes and higher mortality than iatrogenic hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients,110,111,114 suggesting that spontaneous hypoglycemia may be a marker of disease severity. Because hypoglycemia may go unrecognized in patients under anesthesia or those who are critically ill,30 frequent glucose monitoring, conservative glucose targets, excellent perioperative provider communication, and treatment algorithms are needed to reduce the risk of intraoperative and postoperative hypoglycemia.

MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES AFTER HOSPITAL DISCHARGE

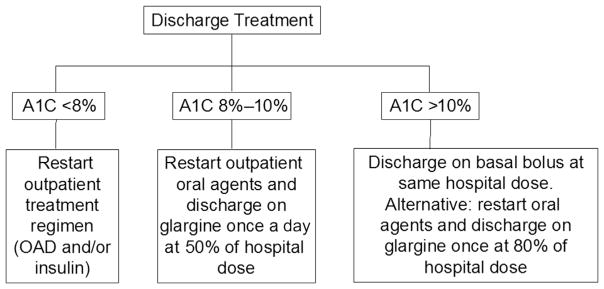

The transition of care from inpatient to the outpatient settings has been determined as a national priority in patients with diabetes.117 The Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals document includes goals and requirements for hospital discharge planning and transitional care. Hospital discharge represents an opportune time to address glycemic control and to adjust home diabetes therapy if necessary. Few studies, however, have focused on the optimal management of hyperglycemia and diabetes after hospital discharge. Clinical guidelines have recommended that patients with diabetes and hyperglycemia have an HbA1c measured to assess preadmission glycemic control and to tailor treatment regimen at discharge. In a recent randomized control trial, the authors’ group validated a discharged patient algorithm based on admission HbA1c, as shown in Fig. 2. Patients with acceptable diabetes control (HbA1c <8%) may be discharged on their prehospitalization treatment regimen (oral agents and/or insulin therapy). Patients with suboptimal glucose control and HbA1c between 8% and 10% should have intensification of therapy, either by adding or increasing the dose of oral agents or by adjusting the dose of basal insulin (approximately 50%). Those with HbA1c greater than 10% should be considered candidates for insulin therapy alone (basal-bolus) or in combination to oral agents.118 When a patient is discharged from the hospital with poorly controlled diabetes or with insulin therapy, a clear strategy for the management of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, and a titration of therapy should be communicated to the community diabetes team and/or primary care team.

Fig. 2.

Hospital discharge algorithm based on admission HbA1c (A1C). OAD, oral antidiabetic drugs. (Adapted from Umpierrez GE, Reyes D, Smiley D, et al. Hospital discharge algorithm based on admission HbA1c for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37(11):2934–9; with permission.)

KEY POINTS.

Perioperative hyperglycemia is common after cardiac surgery and is associated with higher health care resource utilization, longer length of stay, and greater perioperative mortality.

Improvement in glycemic control, in patients with stress hyperglycemia and diabetes, has a positive impact on morbidity and mortality.

A target blood glucose level between 140 mg/dL and 180 mg/dL is recommended for most patients during the perioperative period.

Insulin given by continuous insulin infusion is the preferred regimen for treating hypergly-cemia in critically ill patients.

Subcutaneous administration of basal bolus or basal plus correctional bolus is the preferred treatment of non–critically ill patients.

Footnotes

Disclosure: G.E.U. is partly supported by research grants NIH/NATS UL1 TR002378 from Clinical and Translational Science Award program, and 1P30DK111024-01 from the National Institutes of Health and National Center for Research Resources. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. [Accessed May, 2017];Federation ID 2015. Available at: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/

- 2.Centers for disease control and prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2015. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whang W, Bigger JT., Jr Diabetes and outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction: results from The CABG Patch Trial database. The CABG Patch Trial Investigators and Coordinators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(4):1166–72. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabo Z, Hakanson E, Svedjeholm R. Early postoperative outcome and medium-term survival in 540 diabetic and 2239 nondiabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(3):712–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAlister FA, Man J, Bistritz L, et al. Diabetes and coronary artery bypass surgery: an examination of perioperative glycemic control and outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1518–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho G, Moore A, Qizilbash B, et al. Maintenance of normoglycemia during cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):319–24. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000121769.62638.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmeltz LR, DeSantis AJ, Thiyagarajan V, et al. Reduction of surgical mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients undergoing cardiac surgery with a combined intravenous and subcutaneous insulin glucose management strategy. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):823–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morricone L, Ranucci M, Denti S, et al. Diabetes and complications after cardiac surgery: comparison with a non-diabetic population. Acta Diabetol. 1999;36(1–2):77–84. doi: 10.1007/s005920050149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thourani VH, Weintraub WS, Stein B, et al. Influence of diabetes mellitus on early and late outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67(4):1045–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herlitz J, Wognsen GB, Karlson BW, et al. Mortality, mode of death and risk indicators for death during 5 years after coronary artery bypass grafting among patients with and without a history of diabetes mellitus. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11(4):339–46. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson JL, Scholz PM, Chen AY, et al. Diabetes mellitus increases short-term mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(3):418–23. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01969-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucerius J, Gummert JF, Walther T, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on cardiac surgery outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51(1):11–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weintraub WS, Stein B, Kosinski A, et al. Outcome of coronary bypass surgery versus coronary angioplasty in diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(1):10–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Umpierrez G, Cardona S, Pasquel F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intensive versus conservative glucose control in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: GLUCO-CABG trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1665–72. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krinsley JS, Maurer P, Holewinski S, et al. Glucose control, diabetes status, and mortality in critically ill patients: the continuum from intensive care unit admission to hospital discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(7):1019–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buehler L, Fayfman M, Alexopoulos AS, et al. The impact of hyperglycemia and obesity on hospitalization costs and clinical outcome in general surgery patients. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon S, Thompson R, Dellinger P, et al. Importance of perioperative glycemic control in general surgery: a report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6bbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szekely A, Levin J, Miao Y, et al. Impact of hyperglycemia on perioperative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(2):430–7. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ascione R, Rogers CA, Rajakaruna C, et al. Inadequate blood glucose control is associated with in-hospital mortality and morbidity in diabetic and nondiabetic patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2008;118(2):113–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falciglia M, Freyberg RW, Almenoff PL, et al. Hyperglycemia-related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(12):3001–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b083f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendez CE, Mok KT, Ata A, et al. Increased glycemic variability is independently associated with length of stay and mortality in noncritically ill hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):4091–7. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyper-glycemia in the perioperative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(8):1783–8. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umpierrez GE, Isaacs SD, Bazargan N, et al. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J Clin En-docrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):978–82. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonnell ME, Umpierrez GE. Insulin therapy for the management of hypergly-cemia in hospitalized patients. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41(1):175–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17(1):107–24. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook CB, Kongable GL, Potter DJ, et al. Inpatient glucose control: a glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):E7–14. doi: 10.1002/jhm.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanson CM, Potter DJ, Kongable GL, et al. Update on inpatient glycemic control in hospitals in the United States. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(6):853–61. doi: 10.4158/EP11042.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wexler DJ, Meigs JB, Cagliero E, et al. Prevalence of hyper- and hypoglycemia among inpatients with diabetes: a national survey of 44 U.S. hospitals. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):367–9. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duggan EW, Carlson K, Umpierrez GE. Perioperative hyperglycemia management: an update. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):547–60. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1798–807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greci LS, Kailasam M, Malkani S, et al. Utility of HbA(1c) levels for diabetes case finding in hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):1064–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wexler DJ, Nathan DM, Grant RW, et al. Prevalence of elevated hemoglobin A1c among patients admitted to the hospital without a diagnosis of diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4238–44. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clement S, Braithwaite SS, Magee MF, et al. Management of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):553–91. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrokhi F, Smiley D, Umpierrez GE. Glycemic control in non-diabetic critically ill patients. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(5):813–24. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazurek JA, Hailpern SM, Goring T, et al. Prevalence of hemoglobin A1c greater than 6.5% and 7. 0% among hospitalized patients without known diagnosis of diabetes at an urban inner city hospital. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1344–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):16–38. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Diabetes Association. 14 Diabetes care in the hospital. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S120–7. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1119–31. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lansang MC, Umpierrez GE. Inpatient hyperglycemia management: A practical review for primary medical and surgical teams. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(5 Suppl 1):S34–43. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.83.s1.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edgerton DS, Ramnanan CJ, Grueter CA, et al. Effects of insulin on the metabolic control of hepatic gluconeogenesis in vivo. Diabetes. 2009;58(12):2766–75. doi: 10.2337/db09-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boden G. Gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in health and diabetes. J Investig Med. 2004;52(6):375–8. doi: 10.1136/jim-52-06-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barth E, Albuszies G, Baumgart K, et al. Glucose metabolism and catechol-amines. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S508–18. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000278047.06965.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riad M, Mogos M, Thangathurai D, et al. Steroids. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8(4):281–4. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stentz FB, Umpierrez GE, Cuervo R, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, markers of cardiovascular risks, oxidative stress, and lipid peroxidation in patients with hyperglycemic crises. Diabetes. 2004;53(8):2079–86. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrannini E. The stunned beta cell: a brief history. Cell Metab. 2010;11(5):349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002;106(16):2067–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034509.14906.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, et al. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duchen MR. Roles of mitochondria in health and disease. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 1):S96–102. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montori VM, Bistrian BR, McMahon MM. Hyperglycemia in acutely ill patients. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2167–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandolfi A, Giaccari A, Cilli C, et al. Acute hyperglycemia and acute hyperinsu-linemia decrease plasma fibrinolytic activity and increase plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in the rat. Acta Diabetol. 2001;38(2):71–6. doi: 10.1007/s005920170016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gresele P, Guglielmini G, De Angelis M, et al. Acute, short-term hyperglycemia enhances shear stress-induced platelet activation in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(6):1013–20. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tripathy D, Mohanty P, Dhindsa S, et al. Elevation of free fatty acids induces inflammation and impairs vascular reactivity in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2003;52(12):2882–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dandona P. Endothelium, inflammation, and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2(4):311–5. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhuri A, Umpierrez GE. Oxidative stress and inflammation in hyperglycemic crises and resolution with insulin: implications for the acute and chronic complications of hyperglycemia. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26(4):257–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dandona P, Mohanty P, Chaudhuri A, et al. Insulin infusion in acute illness. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2069–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI26045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohanty P, Hamouda W, Garg R, et al. Glucose challenge stimulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by leucocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(8):2970–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, et al. Insulin inhibits the pro-inflammatory transcription factor early growth response gene-1 (Egr)-1 expression in mononuclear cells (MNC) and reduces plasma tissue factor (TF) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):1419–22. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deedwania P, Kosiborod M, Barrett E, et al. Hyperglycemia and acute coronary syndrome: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(1):14–24. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817dced3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacobi J, Bircher N, Krinsley J, et al. Guidelines for the use of an insulin infusion for the management of hyperglycemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3251–76. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182653269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, et al. Intraoperative hyperglycemia and peri-operative outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(7):862–6. doi: 10.4065/80.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, et al. Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional glucose management during cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):233–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hua J, Chen G, Li H, et al. Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional insulin therapy during cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26(5):829–34. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desai SP, Henry LL, Holmes SD, et al. Strict versus liberal target range for peri-operative glucose in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(2):318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lazar HL, McDonnell MM, Chipkin S, et al. Effects of aggressive versus moderate glycemic control on clinical outcomes in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):458–63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c5d78. discussion: 63–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lazar HL, Chipkin SR, Fitzgerald CA, et al. Tight glycemic control in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients improves perioperative outcomes and decreases recurrent ischemic events. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1497–502. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121747.71054.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pezzella AT, Holmes SD, Pritchard G, et al. Impact of perioperative glycemic control strategy on patient survival after coronary bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(4):1281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blaha J, Mraz M, Kopecky P, et al. Perioperative tight glucose control reduces postoperative adverse events in nondiabetic cardiac surgery patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):3081–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van den Berghe G, Wouters PJ, Bouillon R, et al. Outcome benefit of intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill: Insulin dose versus glycemic control. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(2):359–66. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000045568.12881.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schnipper JL, Magee M, Larsen K, et al. Society of Hospital Medicine Glycemic Control Task Force summary: practical recommendations for assessing the impact of glycemic control efforts. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5 Suppl):66–75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seley JJ, D’Hondt N, Longo R, et al. Position statement: inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(Suppl 3):65–9. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1359–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125(5):1007–21. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Finfer S, Liu B, Chittock DR, et al. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1108–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chan RP, Galas FR, Hajjar LA, et al. Intensive perioperative glucose control does not improve outcomes of patients submitted to open-heart surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64(1):51–60. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Furnary AP, Zerr KJ, Grunkemeier GL, et al. Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67(2):352–60. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00014-4. discussion: 60–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ingels C, Debaveye Y, Milants I, et al. Strict blood glucose control with insulin during intensive care after cardiac surgery: impact on 4-years survival, dependency on medical care, and quality-of-life. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2716–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li JY, Sun S, Wu SJ. Continuous insulin infusion improves postoperative glucose control in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(4):445–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davidson PC, Steed RD, Bode BW. Glucommander: a computer-directed intravenous insulin system shown to be safe, simple, and effective in 120,618 h of operation. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2418–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goldberg PA, Siegel MD, Sherwin RS, et al. Implementation of a safe and effective insulin infusion protocol in a medical intensive care unit. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):461–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kreider KE, Lien LF. Transitioning safely from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(5):23. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gianchandani R, Umpierrez GE. Inpatient use of computer-guided insulin devices moving into the non-intensive care unit setting. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(10):673–5. doi: 10.1089/dia.2015.0213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newton CA, Smiley D, Bode BW, et al. A comparison study of continuous insulin infusion protocols in the medical intensive care unit: computer-guided vs. standard column-based algorithms. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):432–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dungan K, Hall C, Schuster D, et al. Comparison of 3 algorithms for Basal insulin in transitioning from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin in stable patients after cardiothoracic surgery. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(5):753–8. doi: 10.4158/EP11027.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hsia E, Seggelke S, Gibbs J, et al. Subcutaneous administration of glargine to diabetic patients receiving insulin infusion prevents rebound hyperglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3132–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramos P, Childers D, Maynard G, et al. Maintaining glycemic control when transitioning from infusion insulin: a protocol-driven, multidisciplinary approach. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):446–51. doi: 10.1002/jhm.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schmeltz LR, DeSantis AJ, Schmidt K, et al. Conversion of intravenous insulin infusions to subcutaneously administered insulin glargine in patients with hyper-glycemia. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(6):641–50. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Malley CW, Emanuele M, Halasyamani L, et al. Bridge over troubled waters: safe and effective transitions of the inpatient with hyperglycemia. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5 Suppl):55–65. doi: 10.1002/jhm.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dungan K, Hall C, Schuster D, et al. Differential response between diabetes and stress-induced hyperglycaemia to algorithmic use of detemir and flexible mealtime aspart among stable postcardiac surgery patients requiring intravenous insulin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(12):1130–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Olansky L, Sam S, Lober C, et al. Cleveland Clinic cardiovascular intensive care unit insulin conversion protocol. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(3):478–86. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.DeSantis AJ, Schmeltz LR, Schmidt K, et al. Inpatient management of hypergly-cemia: the Northwestern experience. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(5):491–505. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes (RABBIT 2 trial) Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2181–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Jacobs S, et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus insulin therapy in the inpatient management of patients with type 2 diabetes undergoing general surgery (RABBIT 2 surgery) Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):256–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Umpierrez GE, Hor T, Smiley D, et al. Comparison of inpatient insulin regimens with detemir plus aspart versus neutral protamine hagedorn plus regular in medical patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):564–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bueno E, Benitez A, Rufinelli JV, et al. Basal-bolus regimen with insulin analogues versus human insulin in medical patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial in Latin America. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(7):807–13. doi: 10.4158/EP15675.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bellido V, Suarez L, Rodriguez MG, et al. Comparison of basal-bolus and pre-mixed insulin regimens in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2211–6. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Galindo RJ, Davis GM, Fayfman M, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of glargine and detemir insulin in the management of inpatient hyperglycemia and diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(9):1059–66. doi: 10.4158/EP171804.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Farrokhi F, Klindukhova O, Chandra P, et al. Risk factors for inpatient hypoglycemia during subcutaneous insulin therapy in non-critically ill patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6(5):1022–9. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baldwin D, Zander J, Munoz C, et al. A randomized trial of two weight-based doses of insulin glargine and glulisine in hospitalized subjects with type 2 diabetes and renal insufficiency. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):1970–4. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Hermayer K, et al. Randomized study comparing a Basal-bolus with a basal plus correction insulin regimen for the hospital management of medical and surgical patients with type 2 diabetes: basal plus trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2169–74. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Finfer S, Wernerman J, Preiser JC, et al. Clinical review: consensus recommendations on measurement of blood glucose and reporting glycemic control in critically ill adults. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):229. doi: 10.1186/cc12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kosiborod M, Gottlieb RK, Sekella JA, et al. Performance of the Medtronic Sentrino continuous glucose management (CGM) system in the cardiac intensive care unit. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2014;2(1):e000037. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2014-000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wallia A, Umpierrez GE, Nasraway SA, et al. Round table discussion on inpatient use of continuous glucose monitoring at the International Hospital Diabetes Meeting. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(5):1174–81. doi: 10.1177/1932296816656380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brunner R, Kitzberger R, Miehsler W, et al. Accuracy and reliability of a subcutaneous continuous glucose-monitoring system in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):659–64. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206bf2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thabit H, Hovorka R. Glucose control in non-critically ill inpatients with diabetes: towards closed-loop. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(6):500–9. doi: 10.1111/dom.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gomez AM, Umpierrez GE, Munoz OM, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring versus capillary point-of-care testing for inpatient glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients hospitalized in the general ward and treated with a basal bolus insulin regimen. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2015;10(2):325–9. doi: 10.1177/1932296815602905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klonoff DC, Buckingham B, Christiansen JS, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):2968–79. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Akirov A, Grossman A, Shochat T, et al. Mortality among hospitalized patients with hypoglycemia: insulin-related and non-insulin related. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(2):416–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Boucai L, Southern WN, Zonszein J. Hypoglycemia-associated mortality is not drug-associated but linked to comorbidities. Am J Med. 2011;124(11):1028–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Garg R, Hurwitz S, Turchin A, et al. Hypoglycemia, with or without insulin therapy, is associated with increased mortality among hospitalized patients. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1107–10. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Investigators N-SS, Finfer S, Chittock DR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chow E, Bernjak A, Williams S, et al. Risk of cardiac arrhythmias during hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Diabetes. 2014;63(5):1738–47. doi: 10.2337/db13-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Goyal A, et al. Relationship between spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301(15):1556–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pinto DS, Skolnick AH, Kirtane AJ, et al. U-shaped relationship of blood glucose with adverse outcomes among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(1):178–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Svensson AM, McGuire DK, Abrahamsson P, et al. Association between hyper-and hypoglycaemia and 2 year all-cause mortality risk in diabetic patients with acute coronary events. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(13):1255–61. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.JCAHO. [Accessed May, 2017]; Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx.

- 118.Umpierrez GE, Reyes D, Smiley D, et al. Hospital discharge algorithm based on admission HbA1c for the management of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):2934–9. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]