Abstract

Background

The mouse embryo is ideal for studying human cardiac development. However, laboratory discoveries do not easily translate into clinical findings partially because of histological diagnostic techniques that induce artifacts and lack standardization.

Aim

To present a step-wise approach using 17.6 T MRI, for evaluation of mice embryonic heart and accurate identification of congenital heart defects.

Subjects

17.5-embryonic days embryos from low-risk (non-diabetic) and high-risk (diabetic) model dams.

Study design

Embryos were imaged using 17.6 Tesla MRI. Three-dimensional volumes were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Outcome measures

Embryonic hearts were evaluated utilizing anatomic landmarks to locate the four-chamber view, the left- and right-outflow tracts, and the arrangement of the great arteries. Inter- and intra-observer agreement were calculated using kappa scores by comparing two researchers’ evaluations independently analyzing all hearts, blinded to the model, on three different, timed occasions. Each evaluated 16 imaging volumes of 16 embryos: 4 embryos from normal dams, and 12 embryos from diabetic dams.

Results

Inter-observer agreement and reproducibility were 0.779 (95% CI 0.653–0.905) and 0.763 (95% CI 0.605–0.921), respectively. Embryonic hearts were structurally normal in 4/4 and 7/12 embryos from normal and diabetic dams, respectively. Five embryos from diabetic dams had defects: ventricular septal defects (n = 2), transposition of great arteries (n = 2) and Tetralogy of Fallot (n = 1). Both researchers identified all cardiac lesions.

Conclusion

A step-wise approach for analysis of MRI-derived 3D imaging provides reproducible detailed cardiac evaluation of normal and abnormal mice embryonic hearts. This approach can accurately reveal cardiac structure and, thus, increases the yield of animal model in congenital heart defect research.

Keywords: Cardiac development, Congenital heart defects, Diabetic pregnancy, Mouse heart 3D imaging, 17.6 Tesla MRI

1. Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are the most common type of birth defects, affecting nearly 1% of all births [1–3]. Therefore, both basic scientists and clinical researchers invest time and money in studying CHD’s pathophysiology.

In human fetuses, assessment of the heart structure is done routinely by obstetric ultrasonography, using a segmental sequential analysis of images [4–6]. This step-wise approach is based on the heart morphology and allows description of complex congenital heart malformations in a simple fashion. Sonographic imaging is performed in one single plane [4,7,8] with sequential visualization of the four-chamber view, the outflow tracts and the three-vessel view with almost 90% sensitivity for detection of CHDs [9–11].

Murine models are often used to study human cardiac development, due to the highly similar genome, physiology and cardiovascular anatomy between the mouse and the human [12,13] and the relative ease with which the mouse can be manipulated to mimic human diseases associated with CHDs [14]. Since maternal diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with high rates of CHDs [15,16], the use of diabetic mouse model for studying CHD is common. Currently, most researchers analyze murine embryonic hearts by histological analysis techniques [17]. Although its common use, histological analysis may be limited in terms of identifying cardiac structure for several reasons: (1) tissue preparation and flxation methods may generate specimen artifacts that can lead to misinterpretation of heart structures; (2) histological analysis gives a two-dimensional view of the heart, while comprehensive interpretation of the heart structure usually requires imaging in several planes; and(3) histological analysis is slow, labor-intensive and requires special expertise, which most clinicians do not have. To overcome this, novel techniques for imaging the mouse heart, using CT microscopy [18–20] and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) [21–25], are now emerging. These techniques allow the organ to stay intact during analysis, are easy to use, are highly reproducible and allow three-dimensional manipulation of resultant imaging volumes, thus yielding detailed structural data with fewer uncertainties. Despite this great improvement, there is still a need to standardize the interpretation of three-dimensional images, optimize it, and unify murine cardiac evaluation among researchers.

In this study, we aim to introduce the clinical concept of a step-wise approach for evaluation of the mice embryonic heart. We used embryos from non-diabetic and diabetic mice models (as an experimental model with high rates of CHDs) to validate our technique and standardize it for use by both clinicians and basic science researchers.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. Embryos from wild-type dams

The procedures for animal use were approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male and female wild-type C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and paired overnight. The next morning was designated as embryonic day (E) 0.5 if a vaginal plug was present (8:00 am). Mouse embryos at E17.5 were dissected out of the uteri, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) and fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C for at least 48 h before imaging. We did not use any additional contrast agent.

2.1.2. Embryos from type 1 maternal diabetic dams

Diabetes was induced in C57BL/6 J female mice using streptozotocin (STZ) [26,27]. Briefly, 6 to 8 week old females were intravenously injected daily with 75 mg/kg (140 μL) STZ in the tail vein, over a 2-day period, to induce diabetes. Diabetes was defined as a 12-h fasting blood glucose concentration of ≥250 mg/dL, which usually occurred 3 to 5 days after STZ injection. Because STZ has a very short half-life (30 min) [28], and pregnancy was established 1 to 2 weeks after STZ injection, the STZ was not a complicating factor.

Sustained-release insulin pellets (Linplant, purchased from LinShin) were implanted subcutaneously in diabetic mice to restore euglycemia (glucose concentrations of 80 to 100 mg/dL) before mating [26,27]. Females were mated with wild-type males, and day E0.5 of pregnancy was established as described above and done previously [29]. On E5.5 of pregnancy, insulin pellets were removed to expose the developing embryos to hyperglycemia only during the period of cardiac development (E7.5 to E15.5) [30]. Our previous studies revealed that insulin treatment from E0.5 to E5.5 is essential for successful implantation and prevention of early embryonic absorption due to hyperglycemia [31,32].

2.2. MRI imaging and data acquisition

To prevent the specimens from shifting during imaging, four embryos were put in the same 20-mm plastic tube, which fitted securely in the MRI probe, to support each other. The tube was filled with Fomblin (the Kurt J. Lesker Company, USA), and inserted into 17.6 Tesla (T) vertical MRI (Brucker, Billerica, MA) coil, that is equipped with a micro 2.5 imaging probe and 25-mm, 1H volume coil. Temperature was controlled in all experiments and stabilized to 37 °C. Three dimensional gradient echo (GE) protocol was used to acquire the images using the following parameters: TR/TE: 300/5 ms, and a flip angle of 20°. A three-dimensional field of view of 26 × 20 × 20 mm and a matrix of 512 × 375 × 256 resulted in a voxel resolution of 51 × 53 × 78 μm. The total imaging time for each three-dimensional-GE protocol was 8 h.

2.3. Processing of data by the step-wise approach

Raw datasets were reconstructed using the ImageJ free software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). We utilized the three-dimensional plug-in volume viewer, which allowed us to view and manipulate the three-dimensional pictures in any plane –sagittal, coronal or transverse – to gain the best images of the embryo heart. The first author, an obstetrician with a basic knowledge of the fetal heart (R.G. — non-specialist) and the last author, a certified fetal echocardiography specialist (S.T. — specialist), both without prior experience using the ImageJ software, followed the step-wise methodology to examine the embryonic hearts. All embryos were evaluated by the two authors separately on 3 different occasions in a random fashion, blinded to their diabetic status following the same approach: After selecting one embryo, the situs was determined by identifying spine position, head/tail orientation and the arrangements of the abdominal great vessels with respect to spine at the level of the diaphragm. At the second step, the atrioventricular arrangement at the level of the four-chamber view was noticed. Lastly, the ventriculoarterial arrangements was documented by identifying the left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT); right ventricle outflow tract (RVOT); and the four vessels view (unlike human, the mouse has left and right superior vena cava). Transverse sweep of the image volume from the four chamber view to the four vessels view further demonstrated the “crossover” of the great arteries (GA) and their arrangement following the aortic isthmus and the pulmonary duct connecting to the descending aorta, forming a “V” shape (GA arrangement).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Reproducibility of the images was calculated by comparing first to last examinations for the specialist and non-specialist. Inter-observer agreement was calculated by comparing all images and landmarks obtained by both researchers. Statistical analysis was done by Medcalc (version 13.2.2, Ostend, Belgium) using the kappa test to compare examinations agreements, thus taking into account agreement occurring by chance. General guidelines accept that kappa values of <0 indicate no agreement, values of 0–0.20 as slight agreement, values of 0.21–0.40 as fair agreement, values of 0.41–0.60 as moderate agreement, values of 0.61–0.80 as substantial agreement, and values of 0.81–1 as almost perfect agreement [33].

3. Results

3.1. A step-wise approach for analysis of mice embryonic heart reveals normal heart structure in embryos from non-diabetic dams

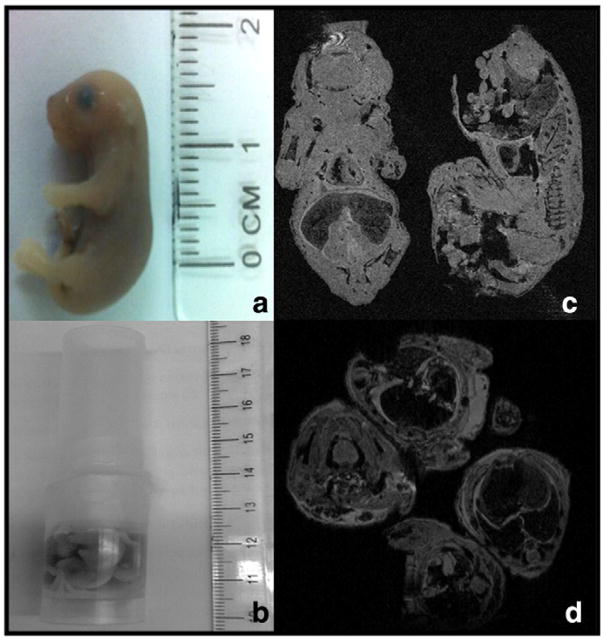

E17.5 embryos were fixed and arranged in a plastic tube (4 embryos per tube) (Fig. 1a and b). The tube was scanned by 17.6 T MRI and three-dimensional embryonic imaging volumes were obtained (Fig. 1c and d). Overall, 16 embryos from different litters underwent imaging: 4 from non-diabetic dams (low risk for CHDs) and 12 from diabetic (high risk for CHDs) dams.

Fig. 1.

Positioning of embryos in 17.6 Tesla MRI coil. (a) True size of 17.5 days embryo from nondiabetic dam; (b) four embryo setting in 20 mm plastic tube prior to insertion to MRI coil; (c and d) preliminary imaging of embryos in coil — sagittal and coronal planes in figure c and transverse plane in figure d.

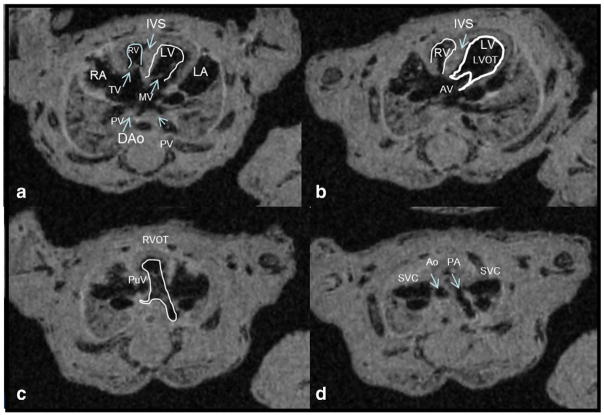

Our methodology was validated on 4 embryos from non-diabetic dams, assuming that all have normal structure hearts. Table 1 depicted the detailed steps to sequentially obtain the four-chamber view, LVOT, RVOT, and four vessels view from embryonic heart imaging volumes using the ImageJ software. To ensure that correct views were obtained, Table 1 lists the key characteristics of each view. Fig. 2a–d shows a typical four-chamber view, a LVOT view, a RVOT view, and a four vessels view, respectively. Transverse sweep of the mouse embryonic heart capturing all four views is attached as supplementary material (supplementary material 1). For all embryos from non-diabetic dams, all views were obtained and all embryos demonstrated normal heart structure.

Table 1.

A step-wise approach for analysis of the mouse embryonic heart.

| Steps | Image views | Validation of correct image |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

A four-chamber view

|

|

| 2 |

A left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT) view

|

|

| 3 |

A right ventricle outflow tract (RVOT) view

|

|

| 4 |

A four-vessel view

|

|

Fig. 2.

A step-wise approach for analysis of the mouse embryonic heart. Sequential segmental analysis of the embryonic mice heart (non-diabetic dam). (a) A four-chamber view: notice all landmarks are pointed on figure — two ventricles right-and-left (LV, RV), two atrias right-and-left (LA, RA), 2 atrioventricular valves mitral and tricuspid (MV, TR), interventricular septum (IVS), pulmonic veins (PV) and the descending aorta (dAo). (b) Left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT) — outflow is marked with visualization of the aortic valve (AV). Notice aorta course from left to right; (c) Right ventricle outflow tract (RVOT) — outflow is marked with visualization of the pulmonary valve (PuV). Notice direction to the spine with branching of the main pulmonary artery; (d) A four vessels view – from R to L – the right superior vena cava (SVC), aorta (Ao), pulmonary artery (PA) and the left SVC.

3.2. Inter- and intra-observer agreement for evaluation of mice embryonic heart using the step-wise analysis

Once technique was validated in the embryos of non-diabetic dams, the specialist and non-specialist used the step-wise analysis approach to independently visualize all 16 embryos, in a random fashion, blinded to their diabetic status. The researchers recorded their observations (designated as “examinations”), and we compared their findings. A total of 96 examinations, 48 examinations for each researcher, were analyzed (16 embryonic hearts examined by 2 researchers on 3 different timed occasions). The four-chamber view was obtained by both researchers for all embryos at all examinations (Table 2). GA arrangement was visualized on all examinations by the fetal echocardiography specialist, and on 46/48 (95%) examinations by the non-specialist researcher. Inter-observer and intra-observer agreement and reproducibility of the imaging views were 0.779 (95% CI 0.653–0.905) and 0.763 (95% CI 0.605–0.921), respectively (kappa values in Tables 2 and 3). These findings suggest that there was no significantdifferencebetweenthespecialistandnon-specialistinrevealing the keyanatomicallandmarksandthefourviewsnecessarytoevaluatethe structure of the mice embryonic heart.

Table 2.

Inter-observer agreement for evaluation of mouse embryonic heart using the step-wise approach.

| Plane/anatomical landmark | Author 1 Non-specialist | Author 2 Fetal echocardiography specialist | Inter-observer agreement (kappa) | Standard error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-chamber view | 48 (100) | 48 (100) | 1 | ||

| Two ventricles | 48 (100) | 48 (100) | 1 | ||

| Two atrias | 44 (92) | 45 (94) | 0.538 | 0.235 | 0.078–0.999 |

| Interventricular septum | 44 (92) | 45 (94) | 0.538 | 0.235 | 0.078–0.999 |

| Atrioventricular valves | 37 (77) | 36 (75) | 0.943 | 0.056 | 0.832–1.000 |

| Descending aorta | 48 (100) | 48 (100) | 1 | ||

| LVOT | 41 (85) | 42 (88) | 0.911 | 0.088 | 0.739–1.000 |

| RVOT | 47 (98) | 48 (100) | 1 | ||

| GA arrangement | 46 (96) | 48 (100) | 1 | ||

| Overall landmarks | 403/432 | 408/432 | 0.779 | 0.064 | 0.653–0.905 |

Ninety-six embryo heart examinations obtained by 2 researchers. Values represents N (% number visualized/all examination). kappa values of <0 indicate no agreement, values of 0–0.20 as slight agreement, values of 0.21–0.40 as fair agreement, values of 0.41–0.60 as moderate agreement, values of 0.61–0.80 as substantial agreement, and values of 0.81–1 as almost perfect agreement.

LVOT — left ventricle outflow tract; RVOT — right ventricle outflow tract; GA — great arteries.

Table 3.

Intra-observer agreement for evaluation of mouse embryonic heart using the step-wise approach.

| Plane/anatomical landmark | First exam | Last exam | Intra observer agreement (kappa) | Standard error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four chamber view | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | 1 | ||

| Two ventricles | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | 1 | ||

| Two atrias | 31 (97) | 29 (91) | 0.475 | 0.306 | 0.124–1.000 |

| Interventricular septum | 29 (91) | 30 (94) | 0.784 | 0.208 | 0.377–1.000 |

| Atrioventricular valves | 24 (75) | 25 (78) | 0.913 | 0.085 | 0.746–1.000 |

| Descending aorta | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | 1 | ||

| LVOT | 27 (84) | 28 (88) | 0.871 | 0.126 | 0.624–1.000 |

| RVOT | 31 (97) | 32 (100) | 1 | ||

| GA arrangement | 30 (94) | 32 (100) | 1 | ||

| Overall landmarks | 270/288 | 272/288 | 0.763 | 0.081 | 0.605–0.921 |

Thirty-two embryo heart examinations obtained by 2 researchers, N (% number visualized/all examination).

LVOT — left ventricle outflow tract; RVOT — right ventricle outflow tract; GA — great arteries.

3.3. A step-wise approach for analysis of mice embryonic heart effectively identifies major heart defects in embryos from diabetic dams

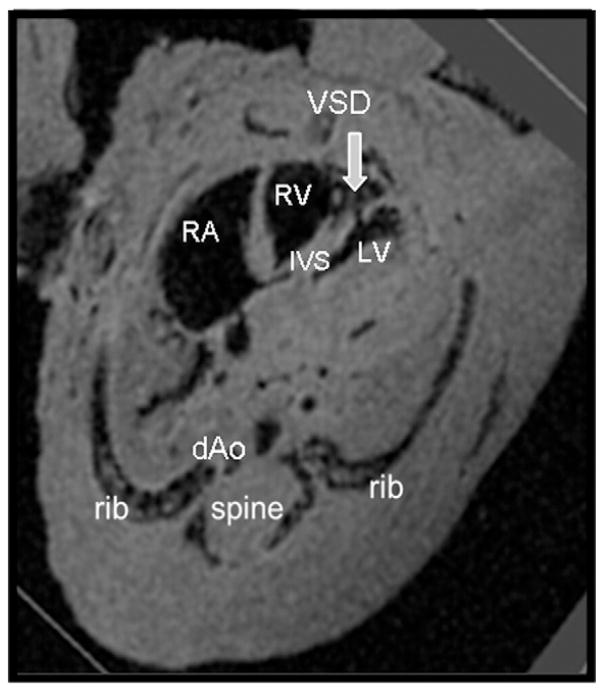

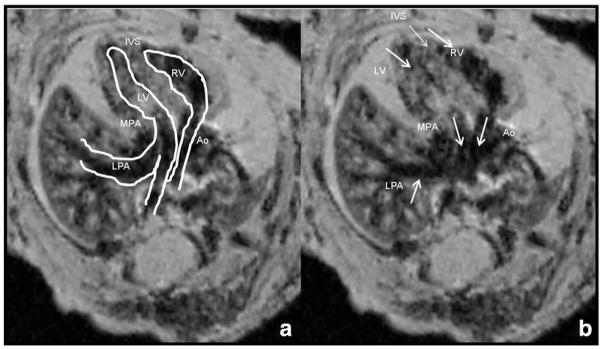

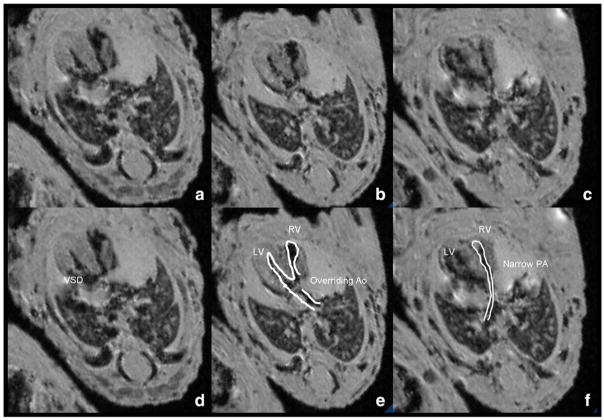

Using the step-wise approach, we identified five embryos exhibiting heart defects (42% CHD’s rate), all from diabetic dams (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Specifically, two embryos had isolated ventricular septal defects (VSD) (Fig. 3), and three embryos had GA abnormalities: two transposition of great arteries (Fig. 4) and one Tetralogy of Fallot (Fig. 5). Transposition of the great arteries was diagnosed by demonstrating the pulmonary artery arising from the left ventricle, branching and entering the lungs and the aorta arising from the right ventricle straight toward the descending aorta. Shifting the images further in the cephalic direction did not demonstrate the four-vessel view. Tetralogy of Fallot was diagnosed as combination of VSD, hypertrophic right ventricle, overriding aorta and pulmonic stenosis. All defects were identified by the specialist and non-specialist. All examinations lasted under 10 min for each embryo, regardless of the performer.

Fig. 3.

Ventricular septal defect in a diabetic model embryo. dAo — descending aorta; IVS — interventricular septum; LV — left ventricle; RV — right ventricle; RA — right atrium; VSD — ventricular septal defect.

Fig. 4.

Transposition of great arteries in a diabetic model embryo. Parallel arrangement of great arteries seen in a diabetic model embryo. The pulmonary artery arising from the left ventricle, branching with its left branch entering the left lung. The aorta is arising from the right ventricle straight toward the descending aorta. When going cephalad in this embryo the normal four-vessel view could not be visualized. MPA — main pulmonary artery; LPA — left pulmonary artery; Ao — aorta; IVS — interventricular septum; LV — left ventricle; RV — right ventricle. Figures are identical with marking of structures on (a). All images are taken sequentially from the same embryo.

Fig. 5.

Conotruncal abnormality in a diabetic model embryo. Note the combination of VSD, thickened heart walls, narrowed right ventricle outlet (pulmonic stenosis) and the aorta, situated above the VSD, connected to both the right and the left ventricle. (a), (b), and (c) are identical to (d), (e), and (f) with marking of structures. Ventricular-septal defect (a and d), overriding aorta (b and e) and narrow pulmonary artery (c and f); PA — pulmonary artery; Ao — aorta; LV — left ventricle; RV — right ventricle; VSD — ventricular septal defect. All images are taken sequentially from the same embryo.

4. Discussion

CHDs are a major public health concern leading to significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Utilizing animal models to gain a better understanding of human CHDs requires the ability to identify the normal from the abnormal structures. Mice are widely used to recapitulate human disease conditions. However, the laboratory methods used to visualize mice hearts are not comparable to the approach used in human studies. Moreover, there is no standardized method for phenotyping the structure of embryonic murine hearts. Unified research techniques that are accepted by both clinicians and basic science researchers are a key element for translational research.

In the present study, we utilized the sequential segmental analysis, which is frequently used in the clinical setting, as a step-wise approach to evaluate the mice embryonic hearts. Embryonic day 17.5 was chosen to evaluate the heart structure after completion of its final organogenesis. Although most human fetal echocardiography examinations are done at late second/early third trimester, the segmental approach is the standard practice for human fetal heart evaluation at any time throughout pregnancy. This step-wise approach was found to be feasible, reproducible and enabled us to accurately identify all of the major anatomical landmarks in the developing murine heart. Analyzing the high-resolution 17.6 T MRI imaging volumes, we revealed the normal heart structures and detected major heart defects, including VSDs, Tetralogy of Fallot and transposition of great arteries, at both the four-chamber and the GA planes. This method may overcome the artifacts and the difficulty of identifying complex CHDs such as Tetralogy of Fallot in conventional histological methods.

Previous studies have used 11.7 T or 7 T MRI imaging for evaluation of the mice embryonic heart [24,25,34]; however, achieving high resolution images in these studies required preliminary preparation of the tissue by contrast agents or sophisticated imaging techniques. In addition, these studies did not describe the process of decoding heart structure but emphasized more on the protocol for achieving the imaging blocks. In our study, 17.6 T MRI generated high resolution images obtained from a straight-forward imaging protocol with no need for contrast agents.

A key strength of our study is that both a specialist with training in fetal echocardiography and a non-specialist (however with knowledge of the developing heart) could easily implement our methodology. The specialist and non-specialist were able to distinguish the normal heart from the abnormal one with a high degree of reproducibility and agreement. Moreover, the MRI derived three-dimensional imaging enabled virtual dissection of the heart in any plane, allowing demonstration of the GA’s arrangement with high accuracy and reproducibility. All this, in a non-destructive way that can be followed by histological analysis, as required. The use of the segmental sequential approach not only standardizes murine heart evaluation but also helps to close the gap between basic scientists and clinical researchers studying CHD’s.

The main limitation of our study is that we did not have histological sections of the murine embryonic hearts to compare with our three-dimensional imaging analyses. However, it can be considered inaccurate to use histological analysis as gold standard for phenotyping murine hearts as it is a two-dimensional approach used to evaluate a three-dimensional organ. In addition, previous studies have shown MRI imaging advantage over histological methods in detecting murine hearts defects [22]. Additionally, this step-wise segmental approach is applicable to any type of three-dimensional imaging, and is not exclusive to high-resolution 17.6 T MRI. Nevertheless, our approach must be validated across multiple model systems before it can be adopted as a tool by basic scientists and clinicians with proven accuracy, reliability and reproducibility. Lastly, we euthanized the mice and embryos prior to imaging. Although technology enables in vivo MRI imaging of animal model hearts [35,36], respiratory and cardiac motion still presents practical challenges that are not easy to overcome.

In conclusion: (1) 17.6 T MRI imaging coupled with the step-wise analysis is an effective tool for revealing the normal and defective embryonic heart structures in both low and high risk murine models of CHDs. (2) This unified approach can be applied and understood by both basic scientists and clinicians and may help move translational research closer to clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

NIHR01DK083243, R01DK101972 (P.Y.) and R01DK103024 (to P.Y. and E.A.R.), and an American Diabetes Association Basic Science Award (1-13-BS-220).

We thank Dr. Julie Wu, Offices of the Dean and Public Affairs, University of Maryland School of Medicine, for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2016.08.008.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Heron M, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: leading causes for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;58(8):1–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman JL, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890–900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in Atlanta, 1998–2005. J Pediatr. 2008;153:807–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donofrio MT, Moon-Grady AJ, Hornberger LK, Copel JA, Sklansky MS, Abuhamad A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(21):2183–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437597.44550.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turan S, Turan OM, Ty-Torredes K, Harman CR, Baschat AA. Standardization of the first-trimester fetal cardiac examination using spatiotemporal image correlation with tomographic ultrasound and color Doppler imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;33:652–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinoza J, Hassan SS, Gotsch F, Kusanovic JP, Lee W, Erez O, et al. A systematic approach to the use of the multiplanar display in evaluation of abnormal vascular connections to the fetal heart using 4-dimensional ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(11):1461–7. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.11.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of fetal echocardiography. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32(6):1067–82. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology et al. ISUOG practice guidelines (updated): sonographic screening examination of the fetal heart. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(3):348–59. doi: 10.1002/uog.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Bianco A, Russo S, Lacerenza N, Rinaldi M, Rinaldi G, Nappi L, et al. Four chamber view plus three-vessel and trachea view for a complete evaluation of the fetal heart during the second trimester. J Perinat Med. 2006;34:309–12. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2006.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk JS, Riggs TW, Comstock CH, Lee W, Yang SS, Weinhouse E. Prenatal screening for cardiac anomalies: the value of routine addition of the aortic root to the four chamber view. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:427–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marek J, Tomek V, Skovranek J, Povysilova V, Samanek M. Prenatal ultrasound screening of congenital heart disease in an unselected national population: a 21-year experience. Heart. 2011;97:124–30. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.206623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. RHW, Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420(6915):520–62. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wessels A, Sedmera D. Developmental anatomy of the heart: a tale of mice and man. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15(3):165–76. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsthuis T, Christoffels VM, Anderson RH, Moorman AF. Can recent insights into cardiac development improve our understanding of congenitally malformed hearts? Clin Anat. 2009;22(1):4. doi: 10.1002/ca.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore T. Maternal-fetal medicine: principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowland TW, Hubbell JP, Jr, Nadas AS. Congenital heart disease in infants of diabetic mothers. J Pediatr. 1973;83:815–20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schleiffarth JR, Person AD, Martinsen BJ, Sukovich DJ, Neumann A, Baker CV, et al. Wnt5a is required for cardiac outflow tract septation in mice. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(4):386–91. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180323810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson JT, Hansen MS, Wu I, Healy LJ, Johnson CR, Jones GM, et al. Virtual histology of transgenic mouse embryos for high-throughput phenotyping. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(4):e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metscher BD. Micro CT for developmental biology: a versatile tool for high-contrast 3D imaging at histological resolutions. Dev Dyn. 2009;238(3):632–40. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degenhardt K, Wright AC, Horng D, Padmanabhan A, Epstein JA. Rapid 3D phenotyping of cardiovascular development in mouse embryos by micro-CT with iodine staining. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(3):314–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.918482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith BR. Magnetic resonance microscopy in cardiac development. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52(3):323–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010201)52:3<323::AID-JEMT1016>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider JE, Bamforth SD, Farthing CR, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Bhattacharya S. Rapid identification and 3D reconstruction of complex cardiac malformations in transgenic mouse embryos using fast gradient echo sequence magnetic resonance imaging. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(2):217–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(02)00291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petiet AE, Kaufman MH, Goddeeris MM, Brandenburg J, Elmore SA, Johnson GA. High-resolution magnetic resonance histology of the embryonic and neonatal mouse: a 4D atlas and morphologic database. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(34):12331–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805747105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zouagui T, Chereul E, Janier M, Odet C. 3D MRI heart segmentation of mouse embryos. Comput Biol Med. 2010;40(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turnbull DH, Mori S. MRI in mouse developmental biology. NMR Biomed. 2007;20(3):265–74. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Weng H, Xu C, Reece EA, Yang P. Oxidative stress-induced JNK1/2 activation triggers proapoptotic signaling and apoptosis that leads to diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2012;61(8):2084–92. doi: 10.2337/db11-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Xu C, Yang P. C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2 and endoplasmic reticulum stress as interdependent and reciprocal causation in diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2013;62(2):599–608. doi: 10.2337/db12-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schein PS, Loftus S. Streptozotocin: depression of mouse liver pyridine nucleotides. Cancer Res. 1968;28(8):1501–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massa V, Savery D, Ybot-Gonzalez P, Ferraro E, Rongvaux A, Cecconi F, et al. Apoptosis is not required for mammalian neural tube closure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(20):8233–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900333106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savolainen SM, Foley JF, Elmore SA. Histology atlas of the developing mouse heart with emphasis on E11.5 to E18. 5. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37(4):395–414. doi: 10.1177/0192623309335060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang P, Zhao Z, Reece EA. Activation of oxidative stress signaling that is implicated in apoptosis with a mouse model of diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:130e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang P, Zhao Z, Reece EA. Involvement of c-Jun N-terminal kinases activation in diabetic embryopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357(3):749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider JE, Böse J, Bamforth SD, Gruber AD, Broadbent C, Clarke K, et al. Identification of cardiac malformations in mice lacking Ptdsr using a novel high-throughput magnetic resonance imaging technique. BMC Dev Biol. 2004;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes WM, McCabe C, Mullin JM, Condon B, Bain MM. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Non invasive self-gated magnetic resonance cardiac imaging of developing chick embryos in ovo. Circulation. 2008;117(21):e346–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.747154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Vinegoni C, Feruglio PF, et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of the beating heart at microscopic resolution. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1054. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.