Abstract

Expanded mutation detection and novel gene discovery for isolated polycystic liver disease (PCLD) are necessary as 50% of cases do not have identified mutations in the seven published disease genes. We investigated a family with 5 affected siblings for which no loss of function variants were identified by whole exome sequencing analysis. SNP genotyping and linkage analysis narrowed the candidate regions to ~8% of the genome, which included two published PCLD genes in close proximity to each other, GANAB and LRP5. Based on these findings, we re-evaluated the exome sequencing data and identified a novel intronic nine base pair deletion in the vicinity of the GANAB exon 24 splice donor that had initially been discarded by the sequence analysis pipelines. We used a minigene assay to show that this deletion leads to skipping of exon 24 in cell lines and primary human cholangiocytes. These findings prompt genomic evaluation beyond the coding region to enhance mutation detection in PCLD and to avoid premature implication of other genes in linkage disequilibrium.

Keywords: polycystic liver disease, GANAB, LRP5, minigene, splice assay

Isolated polycystic liver disease (PCLD) consists of clinically identical liver cysts to those seen as an extra-renal manifestation of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (Qian, et al. (2003). While heterozygous mutations in PKD1 (MIM# 601313) or PKD2 (MIM# 173910), respectively encoding polycystin-1 (PC1) or polycystin-2 (PC2), result in ADPKD, PCLD is caused by heterozygous loss of function mutations in at least seven genes that account for fewer than 50% of cases (Besse, et al., 2017; Cnossen, et al., 2014; Davila, et al., 2004; Drenth, et al., 2003; Li, et al., 2003; Porath, et al., 2016). Five of the PCLD genes (PRKCSH, SEC63, GANAB, ALG8 and SEC61B) encode proteins in the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) involved in protein folding and quality control (Besse, et al., 2017; Davila, et al., 2004; Drenth, et al., 2003; Li, et al., 2003; Porath, et al., 2016). Loss of function mouse and cell models for these five genes show a common mechanism of decreased functional expression of PC1 sufficient to result in kidney and liver cysts (Besse, et al., 2017; Fedeles, et al., 2014; Fedeles, et al., 2011; Porath, et al., 2016). The finding that patients with GANAB (MIM# 104160) mutations can present with PCLD or mild ADPKD reinforces the mechanistic interrelationship between these diseases and suggest the existence of a phenotypic continuum on effective PC1 functional dosage that may be modified by differences in cyst formation thresholds for bile duct and kidney tubules (Besse, et al., 2017; Porath, et al., 2016). A subset of carriers for the autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease gene, PKHD1, can also present with PCLD although the mechanistic relationship to PC1 is unknown (Besse, et al., 2017; Gunay-Aygun, et al., 2011). Finally, LRP5 (MIM# 603506) was implicated as a PCLD gene based on strong linkage data in a well characterized family with 18 affected members coupled with coding region analysis by whole exome sequencing (Cnossen, et al., 2014). Notably, unlike the other six genes, no clear loss of function variants in LRP5 have been implicated in PCLD.

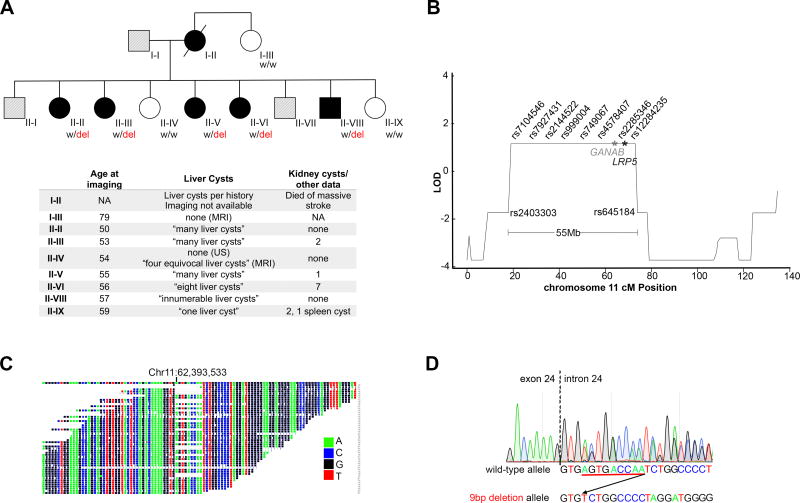

Whole exome sequencing is a DNA fragment capture based method of sequencing the coding regions of the genome which contain ~85% of causative mutations for monogenic diseases (Bamshad, et al., 2011; Choi, et al., 2009; Stenson, et al., 2009). We have studied a cohort of 159 unrelated PCLD cases, most recently by whole exome sequencing with gene burden analysis, and have defined the causative mutation in 73 of these cases (Besse, et al., 2017). One of the remaining unsolved cases in our cohort belonged to a family (T90) in which there were five affected siblings (Figure 1A). Affection status was prospectively determined based on ultrasound and MRI imaging using the published criteria for at-risk family members which require clear visualization of at least 4 liver cysts (Qian, et al., 2003). Whole exome sequencing was performed on individuals II–II and II–III (Figure 1A), but no shared loss of function variants in exons or canonical splice donor/acceptor sites were identified in the published PCLD genes. When the causative genes are unknown and family members are available, sequence based gene discovery can be combined with genetic linkage analysis to define regions of the genome shared among affected members and thereby narrow the list of candidate genes (Cooper and Shendure, 2011; Reynolds, et al., 2000). To reduce the candidate regions of the genome in which pathogenic variants may reside in family T90, we performed SNP genotyping followed by a genome-wide scan for linkage using a multipoint parametric analysis of the curated SNP data under a rare dominant disease model and affected-only analysis. Affected-only analysis was applied because incomplete penetrance PCLD has been reported (Besse, et al., 2017; Cnossen, et al., 2014; Li, et al., 2003; Qian, et al., 2003). The maximum expected LOD score (Zmax) of 1.2 was observed for 16 loci spanning 250 Mb which constitutes approximately 8% of the genome (Supp. Table S1). We next evaluated whether any of the published PCLD genes were present in the linkage intervals and noted both GANAB and LRP5, which are separated by 5.7 Mb, were present in the Zmax linkage interval on chromosome 11 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

We considered these two genes, which are in linkage disequilibrium, as candidates for the causative mutation in family T90. Gene specific coverage with 8 or more sequencing reads for each targeted base was 100% for GANAB and >93% for LRP5 in both individuals (Supp. Table S2). While the lack of a pathogenic variant on exome sequencing does not exclude it as a candidate, we did not find any rare shared variants in LRP5 in this family. The only coding region variants in LRP5 were two synonymous variants and one non-synonymous variant, p.V667M, that has a minor allele frequency of 3.7% in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) (Lek, et al., 2016). V667M was not shared between the affected siblings II-II and II–III despite coverage of at least 22 reads for both individuals (Figure 1A; Supp. Table S3). There were no candidate pathogenic coding sequence mutations in GANAB.

We therefore began our search for pathogenic variants in the previously discarded non-coding regions covered by whole exome sequencing. Non-coding (intronic) variants covered by exome sequencing in LRP5 were all common and either not near splice junctions or not shared (Supp. Table S3). There were two variants shared by the affected siblings in the non-coding sequence available for GANAB. Both occurred in intronic regions but only one, a deletion of nine base pairs from the +4 to +12 positions following the 3’ boundary of exon 24 (NM_198335.3:c.2791+4_2791+12delAGTGACCAA) (Figure 1C, D; Supp. Table S3) was novel in gnomAD, 1000 Genomes, and the Exome Variant Server (Exome_Variant_Server, [accessed 4/2017]; Genomes Project, et al., 2015; Lek, et al., 2016). The variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 1D) and segregated in all five affected members of family T90. It was absent from clinically “indeterminate” family members (I–II, II–IV, II–IX) in whom diagnostic criteria for PCLD were not met. Although located outside the canonical splice donor site, the deletion removes the AGT nucleotide sequence at the +4 to +6 positions which is the most common splice-site consensus sequence at those positions to engage the U2 spliceosome, suggesting it may result in aberrant splicing of GANAB.

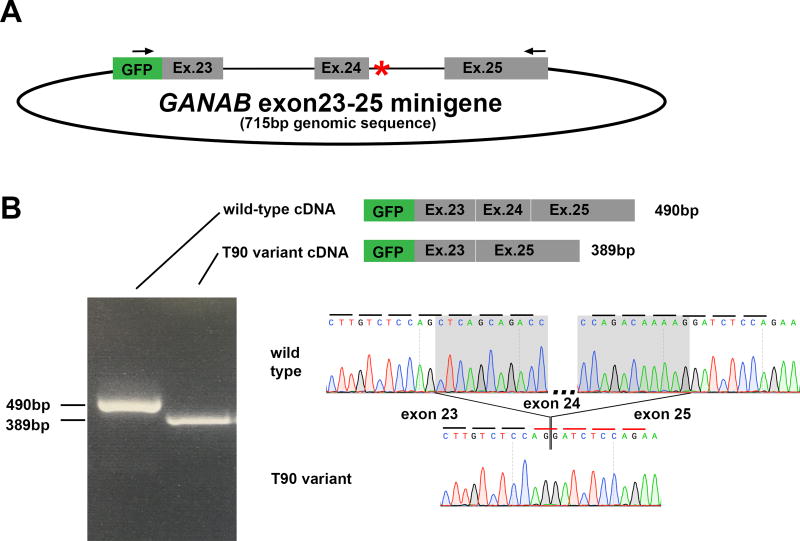

We evaluated the effect of this variant on exon 24 splicing using a splice assay. We constructed a “minigene” expression plasmid containing EGFP fused to either the wild type or family T90 variant genomic sequence of GANAB spanning exons 23 to 25 and including all of the intervening intron sequences (Figure 2A). The constructs were transfected into HEK cells and mRNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, and detected by RT-PCR using forward primer in the EGFP sequence and a reverse primer in exon 25. The resulting amplicon for each construct was a single product with differing migrations for wild type and mutant constructs (Figure. 2B). Sequencing of the wild-type minigene product showed the predicted cDNA sequence for GANAB (Figure 2B). The RT-PCR product from the family T90 mutant minigene instead showed 100% skipping of the 101 bp exon 24 (Figure 2B), splicing exon 23 directly to exon 25, a result which leads to a frameshift and premature termination after exon 23 following the addition of 11 erroneous amino acids.

Figure 2.

Given the potential for cell-type and developmental stage differences in splicing, we validated these results in the precise cell type affected in PCLD, adult human cholangiocytes. We obtained primary human cholangiocytes from a healthy segment of a liver resection cultured in growth media containing human hepatocyte growth factor, epidermal growth factor, triiodothyronine, insulin, and fetal bovine serum, as previously described (Melero, et al., 2002). We performed the minigene assays in these cells and found the wild-type splicing with wild-type minigene and complete skipping of exon 24 with the family T90 variant minigene (Supp. Figure S1).

Exons 24 and 25 of GANAB are highly conserved throughout evolution and are present in all human transcripts that contain the functional domains of the protein product. Importantly, a truncation mutation pathogenic for PCLD has been previously reported in exon 25 of GANAB, downstream of the predicted truncation in family T90 (Besse, et al., 2017; The UniProt, 2017). Minigene plasmids provide a valuable model to evaluate splicing in vitro, when patient RNA is not available. Our minigene contains the entirety of the introns preceding and following exon 24 in order to include all predicted splicing regulatory elements (Cooper, 2005). RT-PCR demonstrates absolute differences between the wild type and patient mutation. There is complete inclusion of exon 24 in the wild type splice sequence and absolute exclusion of exon 24 in the setting of the genomic variant affecting the +4 to +12 positions of the splice donor site. Similar splice site consensus sequence mutations have been reported in other diseases (Krawczak, et al., 1992; Krawczak, et al., 2007). Taken together, the data show that a novel variant resulting in aberrant pathogenic splicing in a known disease gene, GANAB, segregates completely with the affected phenotype among five siblings. We conclude that the intronic variant is causative for PCLD in this family.Beyond defining a novel mutation in this family, there are several implications of our findings. First, non-coding variants, particularly those just beyond the canonical splice donor/acceptor sites should be carefully reviewed for gene discovery or clinical genetic testing when coding variants in established genes are not found. The family T90 variant was initially filtered out by our standard whole exome sequence analysis pipeline due to its intronic annotation. The annotation algorithms dbscSNV and Spidex which score the likelihood of genetic variants either near splice junctions or throughout gene sequences to affect splicing may be helpful with this assessment, however they are not currently designed to evaluate insertions or deletions such as our variant (Jian, et al., 2014; Xiong, et al., 2015). This is just the second report of a non-coding variant outside of canonical splice junctions causing PCLD, and the first in GANAB (Waanders, et al., 2006). Some unexplained cases of PCLD may not be resolved until whole genome sequencing is more readily available and recognition of splice altering variants is more routinely applied to gene discovery.

Second, we note that the close proximity of LRP5 and GANAB on chromosome 11 precludes the use of linkage or segregation analyses alone to distinguish the disease genes in this region. Indeed, in the family of 18 affected members described by Cnossen (Cnossen, et al., 2014), the co-segregation of both the missense variant that implicated LRP5 as a disease gene and the microsatalite marker D11S4117 indicates that a hypothetical variant in GANAB, lying in between these two locations, would be in complete linkage disequillibrium in this family. In light of the subsequent discovery and mechanistic validation of GANAB, the current report suggests that careful evaluation of the coding and non-coding sequence of GANAB in the original reported LRP5 pedigree and additional functional validation of a role of LRP5 in polycystic disease is warranted to validate LRP5 as a causative gene for PCLD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the family presented here for their participation, and the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics (NIH UM1HG006504) for the whole exome sequencing. This study was supported by NIH grants R01 DK51041 and R01 DK100592 to SS; T32 DK007276 and a Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation Fellowship to WB; the Mayo Clinic PKD Center (P30 DK090728, to VET); and the Yale O’Brien Kidney Center (P30 DK079310). The human cholangiocyte cell line research reported in this publication was supported by the Translational Core of the Yale Liver Center of the NIDDK under award number P30DK034989.

Footnotes

The authors have no competing financial interests to disclose.

References

- Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Emond MJ, Nickerson DA, Shendure J. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(11):745–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse W, Dong K, Choi J, Punia S, Fedeles SV, Choi M, Gallagher AR, Huang EB, Gulati A, Knight J, et al. Isolated polycystic liver disease genes define effectors of polycystin-1 function. J Clin Invest. 2017 doi: 10.1172/JCI90129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W, Liu T, Tikhonova IR, Zumbo P, Nayir A, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Sanjad S, et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19096–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910672106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnossen WR, te Morsche RH, Hoischen A, Gilissen C, Chrispijn M, Venselaar H, Mehdi S, Bergmann C, Veltman JA, Drenth JP. Whole-exome sequencing reveals LRP5 mutations and canonical Wnt signaling associated with hepatic cystogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(14):5343–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309438111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM, Shendure J. Needles in stacks of needles: finding disease-causal variants in a wealth of genomic data. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(9):628–40. doi: 10.1038/nrg3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TA. Use of minigene systems to dissect alternative splicing elements. Methods. 2005;37(4):331–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila S, Furu L, Gharavi AG, Tian X, Onoe T, Qian Q, Li A, Cai Y, Kamath PS, King BF, et al. Mutations in SEC63 cause autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36(6):575–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenth JP, te Morsche RH, Smink R, Bonifacino JS, Jansen JB. Germline mutations in PRKCSH are associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33(3):345–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exome_Variant_Server. Seattle, WA: [accessed 4/2017]. NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [accessed 4/2017] [Google Scholar]

- Fedeles SV, Gallagher AR, Somlo S. Polycystin-1: a master regulator of intersecting cystic pathways. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20(5):251–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedeles SV, Tian X, Gallagher AR, Mitobe M, Nishio S, Lee SH, Cai Y, Geng L, Crews CM, Somlo S. A genetic interaction network of five genes for human polycystic kidney and liver diseases defines polycystin-1 as the central determinant of cyst formation. Nat Genet. 2011;43(7):639–47. doi: 10.1038/ng.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunay-Aygun M, Turkbey BI, Bryant J, Daryanani KT, Gerstein MT, Piwnica-Worms K, Choyke P, Heller T, Gahl WA. Hepatorenal findings in obligate heterozygotes for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104(4):677–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian X, Boerwinkle E, Liu X. In silico prediction of splice-altering single nucleotide variants in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(22):13534–44. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M, Reiss J, Cooper DN. The mutational spectrum of single base-pair substitutions in mRNA splice junctions of human genes: causes and consequences. Hum Genet. 1992;90(1–2):41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00210743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M, Thomas NS, Hundrieser B, Mort M, Wittig M, Hampe J, Cooper DN. Single base-pair substitutions in exon-intron junctions of human genes: nature, distribution, and consequences for mRNA splicing. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(2):150–8. doi: 10.1002/humu.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Davila S, Furu L, Qian Q, Tian X, Kamath PS, King BF, Torres VE, Somlo S. Mutations in PRKCSH cause isolated autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(3):691–703. doi: 10.1086/368295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melero S, Spirli C, Zsembery A, Medina JF, Joplin RE, Duner E, Zuin M, Neuberger JM, Prieto J, Strazzabosco M. Defective regulation of cholangiocyte Cl−/HCO3(−) and Na+/H+ exchanger activities in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35(6):1513–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath B, Gainullin VG, Cornec-Le Gall E, Dillinger EK, Heyer CM, Hopp K, Edwards ME, Madsen CD, Mauritz SR, Banks CJ, et al. Mutations in GANAB, Encoding the Glucosidase IIalpha Subunit, Cause Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(6):1193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Q, Li A, King BF, Kamath PS, Lager DJ, Huston J, 3rd, Shub C, Davila S, Somlo S, Torres VE. Clinical profile of autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37(1):164–71. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DM, Falk CT, Li A, King BF, Kamath PS, Huston J, 3rd, Shub C, Iglesias DM, Martin RS, Pirson Y, et al. Identification of a locus for autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease, on chromosome 19p13.2-13.1. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(6):1598–604. doi: 10.1086/316904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenson PD, Ball EV, Howells K, Phillips AD, Mort M, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: providing a comprehensive central mutation database for molecular diagnostics and personalized genomics. Hum Genomics. 2009;4(2):69–72. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt C. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waanders E, te Morsche RH, de Man RA, Jansen JB, Drenth JP. Extensive mutational analysis of PRKCSH and SEC63 broadens the spectrum of polycystic liver disease. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(8):830. doi: 10.1002/humu.9441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong HY, Alipanahi B, Lee LJ, Bretschneider H, Merico D, Yuen RK, Hua Y, Gueroussov S, Najafabadi HS, Hughes TR, et al. RNA splicing. The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science. 2015;347(6218):1254806. doi: 10.1126/science.1254806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.