Abstract

Alcohol misuse and associated negative consequences experienced by college students persists as a public health concern. Quantitative studies demonstrate variability in subjective evaluations of consequences, and how positively or negatively consequences are evaluated is associated with drinking behavior. Lacking is a qualitative exploration of how drinkers evaluate consequences and what influences those evaluations. We conducted a series of single-gender focus groups (13 groups; 3–7 per group; n=62, 48% female) with college student drinkers. Questions focused on: (a) types of negative and positive consequences experienced (b) personal perceptions of negative consequences and (c) factors influencing those perceptions. Verbatim transcripts were content analyzed using applied thematic analysis with NVivo software. Several negative consequences not included in current assessment tools emerged. Reactions to these “negative” consequences of alcohol misuse were not labeled as uniformly negative by participants. Contextual influences on reactions to consequences included: social factors (e.g., normative perceptions, social context, discussions with friends), level of intoxication, concurrent positive consequences, time, and alcohol as an excuse. Future research should focus on consequence measure development and examine interactions between contextual and individual influences on subjective consequence evaluations.

Keywords: alcohol consequences, subjective evaluations, qualitative, context, college students

Introduction

Over one third of college students report engaging in heavy episodic drinking (HED) (4+/5+ drinks in a single sitting for females/males) at least once in the past 2 weeks (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010). This type of risky drinking is accompanied by substantial negative consequences, with annual rates of 646,000 physical assaults, 97,000 sexual assaults, 599,000 unintentional injuries, and even 1,825 deaths (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Alcohol use disorders are also prevalent, with 32% and 6% of college students meeting DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence, respectively (Knight et al., 2002). A better understanding of the causes and effects of HED among college students is needed to develop effective interventions aimed at this population. Paradoxical research findings indicate that college students do not view all ostensibly negative drinking consequences in a negative light. To gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, the present study involved a qualitative examination of the ways in which alcohol-related consequences are subjectively evaluated by heavy drinking college students.

Behavioral learning theories suggest that if consequences of drinking suppress drinking behavior, they can be considered negative or punishing. However, college students continue to drink, and drink heavily, in spite of “negative” consequences. In some cases, a history of alcohol consequences predicts increases in future drinking behavior (Mallett, Marzell, & Turrisi, 2011; Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007; Read, Wardell, & Bachrach, 2012). Social learning theory extends behavioral learning theories to suggest that an individual’s behavior is learned in part by personal experience, but also vicariously (through the observations of and perceptions about the behavior of others). This theory also highlights the role of cognition in guiding drinking behavior (Maisto, Carey, & Bradizza, 1999). That is, it may be the way individuals think about or interpret their consequences, not just the consequences/events themselves, that predicts later behavior. If an individual is not experiencing effects of alcohol that he or she personally perceives as aversive, then why would we expect change?

Research demonstrates that students subjectively evaluate the consequences of their drinking in unexpected, often paradoxical ways (Mallett, Bachrach, & Turrisi, 2008; Patrick & Maggs, 2011; White & Ray, 2013), rating ostensibly negative consequences as neutral or even positive experiences. In one of the first studies to demonstrate this, out of 16 consequences assessed, only getting a bad grade was subjectively evaluated as uniformly negative, with surprising findings that “negative” consequences of hangovers and binge eating while intoxicated were evaluated as positive by about 25% of the sample (Mallett et al., 2008). Patrick and Maggs (2011) also challenged assumptions, finding that researcher-defined negative outcomes of drinking were rated as neutral or positive by between 11% (getting in trouble with police or authorities) and 34% (doing or saying something embarrassing) of students in their sample. Similarly, White and Ray (2013) observed that, among 18–24 year old students and non-students, consequences such as missing work or school, being avoided by relatives, or going to work or school drunk, were rated as “not bothersome at all” by more than 25% of the sample. Notably, 12% of participants were not bothered at all by blackouts, a consequence that researchers or clinicians might deem severe. Most recently, Barnett, Merrill, Kahler, and Colby (2015) demonstrated that on average, those who experienced consequences such as getting into a physical fight or being injured were only “a little” bothered by those experiences. Together, these studies indicate that clinicians and researchers do not have the final word on what counts as a negative consequence.

Subjective evaluations of negative consequences have practical importance to the extent that they predict reductions in drinking. In the first prospective study examining the predictive value of consequence evaluations, Merrill, Read and Barnett (2013) used weekly web-based surveys with college students and found that more negative evaluations of the consequences experienced during one week predict reductions in the next week’s drinking and number of negative consequences. While 42% of the variability in evaluations was due to differences between participants, the other 58% was due to differences within-person, across time. That is, evaluations of consequences made by the same person may differ from one occasion to another. Barnett et al. (2015) replicated these findings, using bi-weekly assessments over the course of two years, while controlling for positive consequence experiences and evaluations. Because subjective evaluations of recent negative consequences are predictive of naturalistic change in drinking, they are an intervention point opportunity and deserve additional research attention.

Little research has been done to examine the factors that may explain between- and within-subject variability in subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences. Research examining individual-level correlates showed that females, older participants, and those who experienced consequences more frequently evaluated consequences as more bothersome, whereas college vs. non-college status was not associated with consequence evaluations (White & Ray, 2013). A second study also found that more negative evaluations of recent consequences were associated with higher levels of past year consequences, as well as higher descriptive norms (i.e., perceptions that consequences were more common) (Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013). This latter finding seems inconsistent with theories highlighting links between norms and personal attitudes (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior; Ajzen, 1988), which would suggest that viewing consequences as normative would be associated with less negative evaluations of those consequences. Because variation in subjective evaluations of consequences is observed not only between- but also within-individuals, it appears that subjective evaluations are a moving target that may depend on contextual-level factors (Merrill, Read, & Barnett, 2013). Also important, then, is understanding what might predict whether a student evaluates a given consequence negatively on one occasion versus another.

One recent study did examine a handful of weekly-level predictors of more negative evaluations (Merrill, Subbaraman, & Barnett, 2016). This study revealed that consequences were rated as more aversive on weeks characterized by (a) lower levels of alcohol use, (b) a greater number of negative consequences, (c) a smaller number of positive consequences, and (d) less positive evaluations of those positive consequences that were experienced. That is, variability in how consequences are rated from week-to-week in part depends on the context in which those consequences occur. However, no studies have examined the contextual predictors of consequences at the event-level.

In sum, the subjective alcohol-related consequence evaluations of young adults vary both between- and within-individuals but the determinants of those evaluations, particularly at the within-person level, are poorly understood. Subjective consequence evaluations, however, predict naturalistic changes in drinking and thus may be useful in guiding intervention strategies. The paradox of how “negative” consequences are viewed in a positive light may help to explain why students continue to drink in the face of consequences that some would consider punishing.

Qualitative research aims to understand how people account for, take action, and otherwise manage their day-to-day situations (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Qualitative methods can provide alcohol researchers with valuable tools for scientific inquiry, allowing for in-depth descriptions of the meanings individuals attach to substance use and the processes by which such meanings are created (Neale, Allen, & Coombes, 2005). Such methods are ideal for exploring the details of young adults’ lived drinking experiences and to gain insight into why HED occurs and how it is understood in different contexts. Prior qualitative and/or mixed methods studies among college students have been conducted to understand topics such as motivations for drinking (Bulmer et al., 2015; Colby, Colby, & Raymond, 2009), positive and negative expectancies of drinking (Dodd, Glassman, Arthur, Webb, & Miller, 2010; Peterson, Borsari, Mastroleo, Read, & Carey, 2013), the types of positive and negative consequences that result from drinking (Smith & Berger, 2010; Smith, Finneran, & Droppa, 2014; Terry, Garey, & Carey, 2014; Wrye & Pruitt, 2017), and contextual factors influencing decisions to drink responsibly (Barry & Goodson, 2012). However, lacking are qualitative studies about the ways in which college students perceive and evaluate the consequences of their drinking, despite the potential for such work to complement, extend, and help better understand findings of quantitative studies in this area.

The Present Study

To this end, we conducted focus group discussions in order to generate hypotheses about the highly variable, often paradoxical subjective consequence evaluations among college students who regularly engage in HED. Focus group methodology was chosen considering (a) college student drinking is a social and conversational activity and the research team was interested in how students think about, and how they discuss and evaluate the consequences of drinking, and (b) group discussion could allow for normalization of risky behaviors, facilitating free conversation about consequence experiences and evaluations, and (c) focus groups provide opportunities to observe consensus or conflicting opinions (Ulin, 2005). Focus group topics relevant to the present study centered on (a) the types of consequences of drinking that college students report, (b) understanding how “negative” consequences are personally evaluated by the students who experience them, and (b) assessing what factors impact the subjective evaluations of consequences.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N=62, 48% female) were recruited from four urban 4-year universities in the northeastern United States. Participants were eligible if they reported underage drinking status (age 18–20), undergraduate enrollment status, first- or second-year standing, engagement in HED (4 or more standard drinks per sitting for women, 5 or more standard drinks for men) more than twice per month in the last 30 days, and no past month usage of illicit substances other than marijuana, at the time of screening. Recruitment strategies included posting fliers with tear tags on area campuses and in coffee shops, academic buildings and dining halls; biweekly Craigslist ads; and snowball recruitment. Students received $35 cash for participating, and dinner was provided. Table 1 includes descriptive information on this sample, reported upon arrival to the focus group.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| n or Mean (SD) |

% | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.68 (0.65) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 32 | 51.6 |

| Female | 30 | 48.4 |

| Year in School | ||

| Freshman | 47 | 75.8 |

| Sophomore | 14 | 22.6 |

| Junior | 1 | 1.6 |

| Race | ||

| White | 45 | 72.6 |

| African American | 2 | 3.2 |

| Asian | 7 | 11.3 |

| Other | 1 | 1.6 |

| Multi-racial | 6 | 9.7 |

| Unreported | 1 | 1.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 | 11.3 |

| Drinks per occasion | ||

| 1–4 | 29 | 46.8 |

| 5 or more | 33 | 53.2 |

| Frequency of HED | ||

| Never | 1 | 1.6 |

| 1–2×/month | 19 | 30.6 |

| About 1×/week | 28 | 45.2 |

| More than 1×/week | 14 | 22.6 |

| Drinking days/week | 2.03 (0.68) | |

| AUDIT | 9.53 (4.12) |

Note: Though we required weekly HED and freshmen or sophomore standing as eligibility criteria at the time of screening, self-reported characteristics fell outside these ranges for some participants at the time of their participation in the focus group.

Procedures

Following approval of procedures from the Institutional Review Board, 13 focus groups were conducted. Six to eight students were scheduled for each group, in accordance with recommended focus group size of 5–8 (Krueger & Casey, 2014), and an average of 5 participants attended (range 3–7). Groups were stratified by gender (6 male, 7 female) to facilitate free and open discussion of sensitive issues (Ulin, 2005). Upon arrival, students completed written informed consent forms, and because screening data were not kept as study data, again filled out a questionnaire covering basic demographic information, recent alcohol intake, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). The 70–85 minute discussions were held in a comfortable conference room, led by the first author, and assisted by a note taker (Ulin, 2005). The note taker recorded the seating arrangement with anonymous participant numbers, time progressions, levels of consensus and whether or not participants participated equally in the discussion.

Focus groups followed a structured agenda, which evolved slightly over time. The first eight groups began with a segment querying for negative consequences of drinking (e.g., “what types of “not-so-good” things happen when college students drink?” and “What do college students dislike about drinking?”). Parallel questioning was done to elicit positive consequences of drinking. After eight groups we reached saturation on this topic (i.e., no new data was being generated), so in the last five groups we brought a list of previously generated consequences and asked if anything was missing. This list generation and/or review served several purposes: (a) to generate a list of for a planned subsequent ecological momentary assessment study, (b) to get participants talking and acclimated to the group and the topic, and (c) to provide context for later questions.

The remainder of the discussion was centered primarily on the negative, rather than positive consequences of drinking. Relative to negative consequences, there is much less variability in evaluations of positive consequences (e.g., Barnett, Merrill, Kahler & Colby, 2015). Further, it is negative consequences that often serve as motivations for change. As such, a second segment of the group focused on personal evaluations of “negative” consequences (e.g., “What goes through a student’s mind after he/she experiences one of these things?” and “What kinds of feelings does a student have after he/she experiences one of these things?”). In the final five groups, we conducted a task to probe for more detailed answers to these questions. First, we asked participants to identify one alcohol-related consequence in each of three categories: “definitely would”, “definitely would not”, or “might” impact later drinking decisions. Next, they used a worksheet to help them think about and record, in advance of discussion, the types of thoughts and feelings they might have upon experiencing each of those three consequences.

A third segment of the focus group centered on influences on subjective evaluations (e.g., “What determines whether one of these events is viewed as positive or negative by the student experiencing it?”). In the final five groups, a focus on those consequences that “might” impact later drinking decisions provided rich data on this topic.

Debriefs were written following each group, noting major themes, levels of participant interaction, effectiveness of questioning strategies, and potential changes to bring to the next focus group. The discussions were audio recorded, and professionally transcribed. Participants were given privacy/confidentiality reminders at the start of groups, always had the option of excusing themselves, and were encouraged to use aliases and speak in the third person about alcohol experiences of students more generally. Transcripts did not include individual voice identifiers. In one group, because the recorders failed to capture the audio, the facilitator and note taker immediately recorded detailed written impressions which became the source document for that group in lieu of a full transcription. The 4 female participants from this group are included in descriptive data and their source document and worksheet answers were used in our analysis; however, no direct quotes from this group are reported. Level of participation across members within each group was generally equivalent, and efforts were made to encourage diverging viewpoints.

Data Analysis

The research team used an applied thematic analysis approach (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012), a rigorous, yet inductive approach designed to identify and examine themes from textual data. Several techniques were used to augment rigor and credibility of the qualitative analysis, with coding occurring in two major stages. In Stage 1, a preliminary coding structure was derived deductively from the focus group script. Then, the 12 transcripts and one source document were coded by both the first and third author; codes were entered into NVivo10 (QSR International, 2008), with specific subtype coding applied inductively as themes and repetitions emerged from this first pass at coding the data. Initial coding comparison showed interrater agreement rates of 88–100% averaged across transcripts, well above 80% which is considered a requirement for good coding agreement (Guest et al., 2012). During this stage, to address trustworthiness of the coding structure, coders discussed differences and resolved discrepancies.

Once the coding structure had been refined and finalized, the second stage took place. We chose to conduct this second stage because new codes had emerged in later transcripts that we wanted to be sure were coded in earlier transcripts when relevant, and in order to enhance the reliability of application of final codes following several consensus meetings. Specifically, in Stage 2, the first author coded half of all the data and the third author coded the other half. Each then reviewed the others’ coded data, and meetings took place to identify and resolve remaining coding discrepancies. Coding decision details and summaries of in-person discussions of coding were logged in a real time audit trail. Summaries of concepts and themes were generated from reviews of coded data, including both a priori as well as emergent themes. Initially, data within each code was reviewed separately by gender, but few substantive differences were observed (exceptions to this are noted in our results and discussion, below). In the results section, representative verbatim quotes for each theme are presented, when possible. For each quote, we identify whether it came from a male or female as well as the focus group (FG) number.

Results

See Appendix A for a complete list of negative consequences of drinking mentioned by focus group participants in the first eight groups. The list of positive consequences mentioned, which are less the focus of the present study, are included in Supplementary Materials. Within each of the two lists (negative, positive), consequences are grouped into categories (e.g., physical, social) based on researcher-identified similarities among them. We focused conversation on acute consequences that accrue to individuals in the short term and not those that develop over time (e.g., dependence).

We compared the list of negative consequences identified in the present study against three of the most popular negative consequence measures used with college students (see Appendix A). These included the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989), Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Tests (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992), and both the full Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ) as well as the Brief YAACQ (Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). Several negative consequences were named by participants that are not included in these measures. In the remainder of the results section, we describe themes related to the subjective evaluation of the “negative” consequences noted by participants.

Theme 1: Subjective evaluations of “negative” consequences are not uniformly negative

Upon questioning the ways in which students think about or react to these alcohol-related consequences, it became clear that this depends on a host of factors. It was challenging to get answers to questions regarding how students think and feel about alcohol consequences without prompting participants to focus on a particular consequence item; however, the reaction that was described could differ greatly depending on the exact item chosen or on the person responding. As one female participant put it:

“I think a lot of these…can be, like, really bad, like, in some ways. Or…not that bad. Just depends.”

We examined some of the specific words used to describe subjective reactions to consequences. Emotional reactions of negative valence included generally feeling upset or bad, and specifically feeling regretful, guilty, shocked, worried, sad, disgusted, embarrassed, humiliated, or ashamed. Thoughts that participants identified as typical following alcohol consequences included “Unacceptable,” “Ugh, I’m not gonna drink again next week,” “Why did I do that?,” “I can’t believe I did that,” “It’s scary,” “That was not a good situation,” and “I hope no one saw.” Of note, however, participants also described some experiences with words such as “pride”, “acceptable”, or “funny”; and expressed post-consequence thoughts such as “It’s kinda just like part of the college experience” and “Yeah, that was fun. We did some stupid stuff. We had a fight, it’s cool.” In other words, reactions to “negative” consequences were described to not be negative for all people on all occasions. Given the variability in these responses, we chose to focus the current paper on understanding the contextual influences on consequence evaluations.

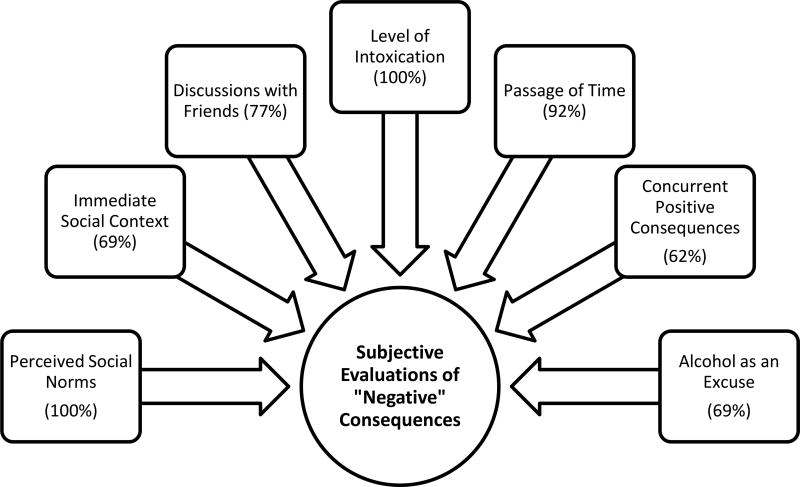

Below we review themes regarding contextual factors that participants identified as influential in determining the subjective evaluation of consequences, in attempts to better understand the within-person variability that exists in consequence evaluations. Many of the themes that emerged from the data were related to social influences on subjective consequence evaluations. Specifically, we found evidence that evaluations may be in part dependent on (a) the perceived social context (i.e., norms), (b) the immediate social context, and (c) discussions with others the next day. Aside from social influences on evaluations, we found that consequence evaluations also may differ as a function of (d) levels of intoxication, (e) passage of time, (f), alcohol as an excuse, and (g) concurrent positive consequences. Each of these themes (2–8) is described next. Additionally, Figure 1 depicts these themes and the percentage of groups (out of 13) in which they were discussed.

Figure 1.

Contextual-level influences on subjective evaluations of consequences and the percentage of 13 focus groups in which they were discussed.

Theme 2: Perceived social norms

Focus group data suggested that both descriptive norms (perceptions about the behavior of peers) and injunctive norms (perceptions about the attitudes of peers) may influence evaluations. These norms may be learned via the media, one’s personal experience, or observation of reactions to others’ experiences in-the-moment. With respect to descriptive norms, students described the idea that knowing others have had similar negative experiences can help to alleviate a negative reaction.

““I think it’s like, reassuring to know that, like, other people have had the same experiences or worse experiences of a similar kind.” (female, FG7).

“…if I was, like, the only person on campus to ever throw up after a night of drinking, I would feel pretty – pretty terrible about myself. I’d be like – not just, like, bad about myself but also think, oh, my God. How could I be the only guy that threw up?” (male, FG12)

With respect to injunctive norms, participants also talked about how some consequences are perceived to be generally acceptable, making one feel less badly about them when they happen personally.

“I mean, some of these are very acceptable, like hangovers. I mean, people joke about hangovers on sitcoms, and children’s television, and whatnot. I mean, it’s just a normal— considered a normal part of drinking and just culture. You’re gonna get a hangover, once in a while.” (male, FG9)

“It’s just like the social sanctioning or social feedback you receive. Or observe other people receiving for a given behavior. So like if someone barfs and everyone’s like ‘oh my god, EMS them right now’ then you’re going to go okay, like it’s really important that I not get so drunk I barf. Someone barfs and all the frat guys are like wow, like yay, then the message is that that’s not that big of a deal.” (female, FG13)

Theme 3: Immediate social context

Participants reported that their specific companions during an alcohol-related consequence can influence the strength and/or magnitude of their personal reaction; evaluations may differ if consequences occur amongst friends versus strangers. Some participants commented that being in the presence of other unknown individuals may make a personal reaction to a consequence less negative.

“So it’s like, you’re in front of everybody from school…people are gonna be there like, ‘Oh, wow. She can’t handle herself.’ But, if you’re like somewhere you’ve never been before and you don’t know anybody, it’s not that big of a deal.” (female, FG7)

On the other hand, it was more often expressed that being among strangers might make the reaction worse.

“…if you’re with your friends, then it just turns into like a fun story—like college story for later on. But if you’re with random people, I—I feel like you might feel a little bit more ashamed.” (female, FG11)

“Being with strangers definitely is a completely different experience than being with your friends who have your back, whereas these people who wouldn’t have it – you don’t know or are, like, you know, semi – it’s, like – it’s a completely –it’s, like, one is scary and one is not as scary.” (male, FG8)

Theme 4: Discussions with friends the next day

Another emergent theme was that students talk with their friends about their drinking experiences, which often serves to alleviate otherwise negative reactions. There were frequent examples of a negative consequence later becoming a funny story to tell. Focus group data were highly saturated with this theme, and men in particular tended to note these next-day conversations as a positive consequence of drinking.

“If you’re like with your close friends, regardless of whether it was a positive or a negative experience, the conversation the next day is always a positive experience, because you’re laughing, regardless of whether you did good things or bad things.” (male, FG6)

Discussions with one’s friends also served to make participants think that the consequences of their own drinking are more normative. This too seemed to result in less negative subjective evaluations of those consequences.

“If you tell your friends something that happened to you, like, thinking, “This is like, a horrible thing,” and then one of them says, like, “Oh, that’s happened to me before,” it can like, lessen the burden. And like, make you feel less guilty or like, less upset about something you did or said.” (female, FG7)

“The usual reaction to sharing something negative is humor or like, ‘Oh it’s not that bad.’”(male, FG6)

Students also reported that they pick and choose with whom they share (e.g., best friends, other drinkers) as well as the particular aspects of the alcohol-related experiences that they share with friends, so as to avoid negative feedback from others.

“I feel like also if you do have a drinking story and it has multiple facets. You’re gonna push all the bad stuff underneath the rug and just, like, glorify the other parts.” (female, FG5)

“You also know who to share it with. I mean, you have the friends that you don’t really talk to about those sorts of things, and the friends that you always meet up with Sunday morning and talk to them about that.” (male, FG6)

Though the idea that discussions with friends typically alleviate negative reactions was expressed consistently, there were a few exceptions. This tended to apply to more severe consequences (e.g., needing emergency transport), in which case students may in fact express their concern about their friend’s behavior. This also applied to blackouts and in particular when a student was told about something he/she did that was not recalled; this may result in a student feeling worse about their drinking event than prior to talking with friends.

“I think with the more serious things like – so take, you know, getting EMSed, for instance. Um. I – it’ll-It’ll definitely be handled in a more serious tone.” (male, FG8)

“I think when people, like, blacked out and then they ask their friends what happens – what happened the previous night, um, they can be, like, very upset upon the answer, especially if you got sick or like, were being very annoying or something.” (female, FG7)

Theme 5: Level of intoxication

Participants conveyed the notion that the initial reaction to an otherwise negative consequence in the moment is often blunted by one’s level of intoxication. In other words, at higher levels of intoxication (when consequences are more likely to occur), a consequence is perceived less negatively at the time it is happening.

“It’s always, “I’ll deal with it in the morning. Whatever.” “ (male, FG8)

“ I think generally, though, people measure the severity of an event sober um, because they consider themselves so altered when they’re drunk. Like not only is this bad thing happening because or maybe exacerbated by the drinking, um, but their perception of it is altered based on the drinking. And so you go—okay, how do I feel the next morning? .” (female, FG13)

Theme 6: Passage of time

The subjective evaluation of a consequence may change from one point in time to another. Participants commented that the most negative reactions occur the morning after the event, when alone with one’s thoughts. However, these negative reactions tend to subside over time.

“…with time, you might, you know, forget like how serious something was and stop worrying about it as much.” (female, FG11)

“Even vomiting like within a day I’m like, ‘Oh, that was horrible.’ Like two days, ‘Oh, that was horrible.’ Maybe two weeks or four weeks later, I’m like, ‘That was—that was kinda funny that I ended up throwing up on that wall over there.’” (male, FG3)

Of note, the influence of the passage of time on consequence evaluations may in part be due to discussions with friends that tend to occur the next morning, as described above.

Theme 7: Alcohol as an excuse

Students reported that if they are able to attribute a consequence/behavior directly to alcohol intoxication (vs some other cause), this can lessen the negative evaluation of that consequence/behavior. They discussed the idea that if one can “blame alcohol” for their behavior or consequences of drinking, they may feel less badly about it. Interestingly, this theme was more often discussed among the female (6/7 groups) than the male participants (3/6 groups).

“…the impacts can be lessened by the fact that you were drinking alcohol.” (male, FG6)

“So it’s saying something stupid and then having the excuse, oh, I was a little bit tipsy. It’s fine.” (female, FG4)

Theme 8: Concurrent positive consequences

Participants indicated that the positive effects of drinking that co-occur with the negative consequences can mitigate a negative reaction to those consequences. This often came up in the context of discussions surrounding blackouts. Participants indicated that some view blacking out as an “adventure” and that it can be fun the next morning to attempt to piece together what occurred the night before. Similarly, the students expressed that more generally the benefits of drinking may outweigh the costs, with an overall perception of a night perhaps involving negative consequences but also some positive consequences as “worth it”. Of note, male participants more frequently discussed the role of concurrent positive consequences (5/6 groups) than did female participants (3/7 groups).

“…even though you – like a couple hours later, you may end up throwing up, and you may have a bad hangover the next day, if the time that you had was good enough, and you felt super confident, then I think you would wake up the next morning and be like oh, I drank too much, but it was worth it.” (male, FG9)

“….maybe if you missed homework or like a class or something, it was like oh, but like the night was really fun, so it was worth it.” (female, FG13)

Discussion

This study is the first qualitative examination of how college drinkers form subjective evaluations of alcohol-related consequences. A more nuanced understanding of how students perceive and describe the consequences of their drinking through qualitative methods was necessary in order to place paradoxical findings of prior quantitative work in the context of students’ lived experiences with drinking, and to begin to round out knowledge of naturalistic change processes in this population. Findings revealed much variability in students’ reactions to those consequences, and in the factors that impact those reactions.

First, we examined the types of negative consequences of drinking that college students report, with an eye toward whether contemporary drinking culture is characterized by experiences not captured on typical consequence measures. Participants in our focus groups identified a range of negative consequences across several domains (Supplementary Material), many of which are not typically assessed with the most common measures used today. Similarly, the structure of our focus group guide allowed us to elicit a comprehensive list of positive consequences college students experience as a result of drinking. These findings may be useful for future measure development, as our focus groups served as an item generation opportunity that has the potential to extend the content validity of alcohol consequence measures for young adults. Next steps could involve developing these extensive lists into survey items, and assessing occurrence of each consequence over the past month or year. Data collected could then be subjected to item and factor analysis in order to identify optimal subsets of items that are both reliable and valid. Psychometric research such as this would determine whether the information provided by our focus group participants could strengthen current measurement tools. We believe that some of those described but not assessed on existing measures (e.g., stumbling, drunk texting) may be experienced frequently. Others (e.g., hospitalization, car accident) are likely low frequency events. However, these may be the types of consequences that are important to study if the purpose of the research is to understand change in drinking behavior as a function of consequences experienced.

Next, we sought to better understand how college students personally react to, or subjectively evaluate, the negative consequences of their drinking, and found that this process was not straightforward. A number of negatively valenced emotions (e.g., embarrassment, guilt, disgust) as well as thoughts (e.g., “why did I do that?”) were reported, but the best answer to this how these events are experienced may simply be “it depends.” As we explored further, we learned that several contextual level variables influence these subjective evaluations.

The robust influence of social factors on consequence evaluations uncovered in this study fits well within social learning theory (SLT) framework. Specifically, we found that consequence evaluations are shaped not only by the immediate social context, but also by the broader social norms one perceives and the way that consequences are discussed among friends later on. Regarding the immediate social context, while some participants indicated that being surrounded by friends (vs strangers) may make one feel less badly about their behavior, others expressed the opposite. It was clear that how any given contextual factor influences a subjective evaluation depends on the person, the consequence at hand, and the specifics of the context.

Permissive social norms, or perceptions that consequences are acceptable and/or common among peers, were an important influence on one’s personal evaluation of a consequence experience, discussed within every single focus group we conducted. This finding is consistent with frameworks that highlight the importance of social norms and learning from the social environment, such as the theory of normative social behavior (Rimal & Real, 2005), theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1988), and SLT (Maisto et al., 1999). While consistent with theory, this finding conflicts with survey study findings (Merrill et al., 2013) indicating that perceptions that consequences are more normative are associated with more negative evaluations. Of note, Merrill et al (2013) used an aggregate score for norms across several consequences, rather than seeking to understand consequence-specific links between norms (for a particular consequence) and evaluations (of that same consequence). The discrepancy in findings highlights the importance of using qualitative research to better understand one’s personal experiences.

Also within the social realm, we gathered evidence that the way students discuss their drinking experiences, often the next day, contributes to the dynamic nature of consequence evaluations. Though this phenomenon of “storytelling” has been observed previously (at least among female drinkers; Smith & Berger, 2010), the way it may shape personal evaluations of consequences has received little attention. Youth may purposely downplay the consequences of their friends’ drinking, in order to make the friend feel better, resulting in a consequence one initially viewed negatively to become more neutral (or even positive, in the case of a funny story) after processing it with a supportive group. This theme regarding the ways in which students discuss the consequences of their drinking fits with the construct of selective disclosure, whereby individuals conceal counter-normative behavior and disclose it selectivity (Kitts, 2003). Such selective disclosure contributes to the development of permissive drinking norms.

We also found evidence for several other (non-social) factors that mitigate negative evaluations, including the presence of positive consequences, level of intoxication, time, and alcohol as an excuse. That concurrent positive consequences ameliorate what might otherwise be a negative evaluation of consequences was consistent with prior research. In a quantitative study, Merrill et al. (2016) demonstrated that on weeks where more positive consequences occurred, and/or on weeks where positive consequences were perceived more positively than usual, negative consequences were perceived less negatively. Subjective Expected Utility Theory (Fischhoff, Goitein, & Shapira, 1981), which views decisions as the result of a reasoned assessment of the positive and negative consequences of a behavior, would suggest that drinking events with positive consequences that outweigh the negatives might result in future decisions to continue drinking in a similar manner. As such, a negative consequence of drinking cannot be expected to necessarily result in behavior change when considered in isolation.

The observation that level of intoxication mitigates negative evaluations of consequences in the moment fits with alcohol myopia theory (Josephs & Steele, 1990), which suggests that when intoxicated, one may to respond almost exclusively to the immediate environment, with limited ability to consider future consequences of his/her actions. Regarding how such evaluations may then change over time, outside of the context of being intoxicated, we learned that an individual may view his/her consequences in the most negative light the morning after they occur. Yet, as the event recedes in memory, negative thoughts and emotions related to the event seem to subside, which holds implications for the best timing of intervention. Finally, we found that a consequence may be viewed as less bothersome if someone can blame it on alcohol, rather than taking more personal responsibility for it. Students may attempt to protect their self-esteem by attributing any uncharacteristic behavior to alcohol, rather than to the self.

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings should be considered in light of study limitations. Although in some ways a strength, the homogeneity of our sample leaves it unclear whether similar themes would emerge among those sampled from other populations, including lighter drinkers, older college students, or non-college attending young adults. This work should be replicated in other groups. Second, while this study was valuable in allowing us to begin to generate hypotheses about influences on the evaluation of consequences, this exploratory, formative work does not lend itself well to quantifying theme frequency or examining statistical significance. A natural next step is to pursue quantitative explanatory work, in which statistical significance of identified themes can be more effectively explored.

Future research also could assess influences on evaluations of the positive impacts of drinking, if trying to gain a comprehensive understanding of later behavior. Our analysis for the present study focused largely on the negative consequences of drinking. Even though we gathered information about the “good” things that happen when college students drink, we did not ask participants about how and why their subjective evaluations of positive experiences may differ from event to event. Of note, research shows that evaluations of traditionally defined positive consequences are less variable than those of negative consequences (Barnett et al., 2015), which suggests that contextual influences on those evaluations are less relevant. Still, it is important to note that students describe that the benefits of drinking are commonly experienced and are important in making decisions about drinking. Indeed, we observed a moderating influence of concurrent positive consequences in the evaluation of negative consequences. Future qualitative work on how students perceive and describe the full range of drinking outcomes (positive, neutral, negative) would be informative.

While we focused this study on contextual influences on consequence evaluations, individual differences are also important. For example, we noted in our results that some contextual influences seemed more salient for women (the ability to blame a consequence on alcohol), while others seemed more salient for men (the role of concurrent positive consequences). Although we did not examine gender differences in detail in this study, future qualitative and quantitative studies could more rigorously test gender differences in these themes. Focus group participants also noted that two students may view the same consequence in an entirely different light, depending on prior experiences. In line with prior quantitative work (Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013; White & Ray, 2013), we found evidence that a repeated experience may result in a more negative evaluation over time, perhaps representing a sensitization process. On the other hand, it was also acknowledged that sometimes the salience of a negative consequence is reduced upon repeated experience, perhaps representing a habituation process. Further, the subjective evaluation of a single experience is likely highly idiosyncratic based on the particular alignment of contextual factors surrounding that consequence experience, as well as individual differences in variables such as drinking severity, motivations and personality. Likewise, overall functioning may play a role. Students who are functioning well in social, academic and health domains may be less apt to react negatively to a drinking consequence compared to students who may be struggling, especially in a domain related to the consequence itself. Variability in such individual difference factors were not measured in this study, leaving their influence unaccounted for. While exploring these issues in depth was beyond the scope of the present study, further research, both qualitative and quantitative, is needed to understand how individual differences and contextual factors may interact to predict subjective consequence evaluations.

Conclusions

How college students perceive the “negative” consequences of drinking varies by individual, consequence type, and by a range of contextual factors. There is no one single theory that accommodates the range of influences on consequence evaluations uncovered in this study. Still, implications for future work are evident, particularly with respect to the assessment of negative alcohol consequences. For example, measures of alcohol-related consequences should perhaps be expanded to reflect contemporary drinking culture, and should not make the assumption that all consequences that researchers view as negative are in fact perceived as such by the students who are experiencing them. Further, the extent to which the same consequence is perceived negatively may differ from one occasion to the next, depending on the contextual factors highlighted in our qualitative work. If the goal is to understand the influence of consequences on future behavior, the fluid nature of consequence evaluations may need to be considered in future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01AA022938) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K24HD062645).

Appendix A. Negative Consequences Identified in Focus Group Discussions

Note: aSimilar item included on RAPI; bSimilar item included on YAAPST, cSimilar item included on B-YAACQ and full YAACQ, dSimilar item included on full YAACQ only

Physical (in-the-moment)

Being forgetful

Being unable to focus

Feeling sick (in the moment) b, c

Throwing up b, c

Stumbling

Feeling dizzy

Getting the spins

Passing out a, c

Falling

Getting physically injured

Impaired sleep cycle d

Slowed reaction time

Reduced coordination

Having to be taken care of by friends

Needing to go to the hospital for an injury

Needing to go to the hospital for intoxication

Alcohol poisoning

Consuming more calories (from alcohol) than you want d

Overeating d

Inflicting self-injury

Physical (identifiable next-day)

Blacking out (waking up and not remembering some part of the night before) a, b, c, d

Waking up somewhere other than your own bed c

Hangovers b, c

Being unable to focus the next day d

Being unproductive the next day c

Having a headache b, c

Feeling sick or nauseous c

Oversleeping the next day

Being unable to do school work the next morning b, c

Personality Change

Getting aggressive a, c, d

Being stubborn

Change in personality (for the worse) a

Social/Interpersonal

Doing something embarrassing c

Getting separated from friends during a night out

Having embarrassing picture taken of you

Making a bad impression on someone

Being judged or made fun of by others for your intoxicated behavior

Getting a bad reputation related to your drinking

Posting something online that you wouldn’t normally post

Drunk texting

Drunk dialing

Getting into physical fights a, b, d

Physically injuring someone else d

Getting into an argument a

Saying things you wouldn’t normally say c, d

Sharing something personal about yourself

Sharing something personal about someone else

Saying something mean or offensive to someone c

Damaging a relationship or friendship b, c

Cheating on a partner

Betraying a friend

Trouble

Getting into trouble with police b

Getting arrested b

Getting a ticket (e.g., for public intoxication, underage drinking)

Getting a DUI b

Getting into trouble with parents

Getting into trouble with the university because of drinking b, d

Risky behavior

Poor decision making c

Making risky decisions c

Getting into a car with someone who has had too much to drink to drive safely

Drinking and driving a, c

Getting into a car accident

Taking other drugs that you wouldn’t normally

Smoking more cigarettes than you normally would

Having unprotected sex

Putting yourself in an unsafe situation, acting in an unsafe way (e.g., walking in the traffic, walking alone at night, leaving a party with someone you don’t know) c

Sexual

Being sexually assaulted

Committing a sexual assault

Hooking up with someone you wouldn’t have hooked up with if you weren’t drunk b, c

Getting taken advantage of sexually

Being promiscuous

Academic/Occupational

Being late to work a, b, c

Missing a shift at work a, b, c

Getting a bad grade b, d

Not doing your school work c

Emotional

Having negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger, sadness) intensified

Feeling depressed or sad (in the moment) d

Crying in public

Other Personal Costs

Trashing/making a mess of your apartment or room

Breaking things b

Spending more money than you wanted to a

Losing control of your actions

Getting lost

Losing things

Getting kicked out of a party, bar or event

Having poor hygiene (e.g., not showering, not brushing teeth)

Urinating in public

Spending too much time drinking c,d

Footnotes

Some of the data in this manuscript were previously presented at the 2015 annual meeting of the Kettil Bruun Society in Munich, Germany.

References

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Milton-Keynes, England: Open University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Colby SM. Negative evaluations of negative alcohol consequences lead to subsequent reductions in alcohol use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(4):992–1002. doi: 10.1037/adb0000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry AE, Goodson P. Contextual factors influencing U.S. college students’ decisions to drink responsibly. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(10):1172–1184. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.690811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulmer SM, Barton BA, Liefeld J, Montauti S, Santos S, Richard M, Lalanne J. Using CBPR Methods in College Health Research. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2015;31(2):232–258. doi: 10.1177/0743558415584012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Colby JJ, Raymond GA. College versus the real world: Student perceptions and implications for understanding heavy drinking among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd VJ, Glassman T, Arthur A, Webb M, Miller M. Why underage college students drink in excess: Qualitative research findings. American Journal of Health Education. 2010;41:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff B, Goitein B, Shapira Z. Subjective expected utility: A model of decision-making. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 1981;32(5):391–399. doi: 10.1002/asi.4630320519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman E. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;(Suppl 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, editors. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2009: Vol. II. College students and adults ages 19–50 (NIH Publication No. 10–7585) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Josephs RA, Steele CM. The two faces of alcohol myopia: Attentional mediation of psychological stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:115–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient andcomprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitts JA. Egocentric Bias or Information Management? Selective Disclosure and the Social Roots of Norm Misperception. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003;66(3):222–237. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):263–270. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. Social learning theory. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 106–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students’ perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Marzell M, Turrisi R. Is reducing drinking always the answer to reducing consequences in first-year college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(2):240–246. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(1):42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Colder CR. Normative perceptions and past-year consequences as predictors of subjective evaluations and weekly drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2625–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Subbaraman MS, Barnett NP. Contextual- and individual-level predictors of alcohol-related consequence aversiveness ratings among college student drinkers. Emerging Adulthood. 2016;4:248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neale J, Allen D, Coombes L. Qualitative research methods within the addictions. Addiction. 2005;100(11):1584–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. College students’ evaluations of alcohol consequences as positive and negative. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Borsari B, Mastroleo NR, Read J, Carey KB. How does the brief CEOA match with self-generated expectancies in mandated students? Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(1):1414–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo 8. Doncaster, Australia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(1):169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, Bachrach RL. Drinking consequence types in the first college semester differentially predict drinking the following year. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;38(1):1464–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal RN, Real K. How Behaviors are Influenced by Perceived Norms: A Test of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior. Communication Research. 2005;32(3):389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Berger JB. Women’s ways of drinking: College women, high-risk alcohol use, and negative consequences. Journal of College Student Development. 2010;51(1):35–49. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Finneran J, Droppa M. High risk drinking among non-affiliated college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2014;58(1):28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Terry DL, Garey L, Carey KB. Where do college drinkers draw the line? A qualitative study. Journal of College Student Development. 2014;55(1):63–74. doi: 10.1353/csd.2014.0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulin PR. Qualitative methods in public health : A field guide for applied research. 1. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Ray AE. Differential evaluations of alcohol-related consequences among emerging adults. Prevention Science. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrye BAE, Pruitt CL. Perceptions of Binge Drinking as Problematic among College Students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2017;61:71–90. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.