Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses long, thin fibres called type IV pili (T4P) for adherence to surfaces, biofilm formation, and twitching motility. A conserved subcomplex of PilMNOP is required for extension and retraction of T4P. To better understand its function, we attempted to co-crystallize the soluble periplasmic portions of PilNOP, using reductive surface methylation to promote crystal formation. Only PilOΔ109 crystallized; its structure was determined to 1.7 Å resolution using molecular replacement. This new structure revealed two novel features: a shorter N-terminal α1-helix followed by a longer unstructured loop, and a discontinuous β-strand in the second αββ motif, mirroring that in the first motif. PISA analysis identified a potential dimer interface with striking similarity to that of the PilO homolog EpsM from the Vibrio cholerae type II secretion system. We identified highly conserved residues within predicted unstructured regions in PilO proteins from various Pseudomonads and performed site-directed mutagenesis to assess their role in T4P function. R169D and I170A substitutions decreased surface piliation and twitching motility without disrupting PilO homodimer formation. These residues could form important protein-protein interactions with PilN or PilP. This work furthers our understanding of residues critical for T4aP function.

Introduction

Type IV pili (T4P) are long, thin (5–8 nm diameter) hair-like appendages which extend from the bacterial surface and promote attachment, cell-cell aggregation, biofilm formation, and twitching motility1–6. T4P – which include two major subfamilies, T4aP and T4bP, that vary in terms of assembly system components – are produced by a wide variety of bacteria and archaea, including the opportunistic pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This bacterium, notorious for its resistance to several classes of antibiotics, infects immunocompromised individuals such as those with severe burns, cystic fibrosis, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)7. Mutants lacking T4aP are impaired in host colonization and thus less infectious8,9. T4aP also mediate twitching motility, a form of flagellum-independent movement caused by repeated rounds of pilus extension, adhesion, and retraction, allowing the bacteria to pull themselves along surfaces1,10. The T4aP system in P. aeruginosa is composed of four subcomplexes that together form a transenvelope machinery3. The outer membrane (OM) secretin is composed of an oligomer of 14 PilQ monomers and their pilotin, PilF, forming a gated pore through which the pilus is extruded11,12. The inner membrane (IM) motor subcomplex is composed of a platform protein PilC13, and three cytoplasmic ATPases, PilBTU14. The secretin and motor subcomplexes are linked by the alignment subcomplex, PilMNOP, with putative roles in control of pilus assembly-disassembly dynamics and gating of the secretin15–17. The final subcomplex is the pilus fibre, which extends from the cell4,18–20. This fibre is composed primarily of PilA monomers plus small amounts of minor pilins (PilVWXE/FimU) and PilY14,19–21. These subcomplexes – plus several regulatory proteins whose functions are not well understood22–25 – form a fully functional T4aP system. PilMNOP are critical for function of the T4aP system3,4,26. Cytoplasmic component PilM is structurally similar to the bacterial actin-like cytoskeletal protein, FtsA27–29. The structures of Thermus thermophilus PilM bound to a PilN N-terminal peptide and a P. aeruginosa PilM-PilN1–12 chimera were recently determined by X-ray crystallography, revealing a PilM binding pocket that interacts with a highly conserved motif in PilN’s N-terminus28–30. Although no structure for PilN from P. aeruginosa is yet available, it is predicted to resemble PilO30. The structure of PilN from T. thermophilus has been determined31, but has a different arrangement of secondary structure elements compared to the predicted structure of PilN from P. aeruginosa. A crystal structure of an N-terminally truncated (Δ1–68) version of a PilO dimer was previously determined (PDB 2RJZ)30, and the observed homodimer interface later shown to be physiologically relevant32. PilN and PilO also form heterodimers15,17,30,33. They are predicted to have similar topologies, with short cytoplasmic N-termini preceding single transmembrane segments (TMS), followed by periplasmic segments consisting of a coiled-coiled domain linked to a core domain containing two ferredoxin-like αββ motifs30. Although PilN and PilO form both homo- and heterodimers in vivo32, the IM-associated lipoprotein PilP binds only PilNO heterodimers through its unstructured N-terminal region17. Finally, the C-terminal β-domain of PilP interacts with the secretin monomer, PilQ16. These protein-protein interactions form a continuous network through the periplasm, as confirmed by a recent 4 nm cryoelectron tomographic model of the Myxococcus xanthus T4aP system34.

To better characterize physical interactions between alignment subcomplex components, we took a structural approach. Previously, we showed that soluble periplasmic fragments of PilNOP form a stable heterotrimeric complex in vitro17. During a series of systematic attempts to crystallize this stable heterotrimer, we used reductive methylation to promote crystal formation35. Although the resulting crystals diffracted to 1.7Å, they were ultimately found to contain only one member of this subcomplex, PilO. The structure of the PilOΔ109 monomer was solved by molecular replacement using our previous 2.2Å PilOΔ68 structure (PDB 2RJZ) as a template30, revealing novel features, including a shorter N-terminal α1-helix and an additional discontinuous β-strand. We identified highly conserved residues that mapped to largely unstructured regions on the PilO structure, and investigated their roles in T4aP function through mutagenesis and phenotypic assays. Alteration of two of the highly conserved residues resulted in reduced piliation and motility, potentially by perturbation of PilO interactions with itself or other partners. These data lend further insight into the function of this key alignment subcomplex component.

Results

A new 1.7 Å crystal structure of PilOΔ109 reveals novel secondary structure features

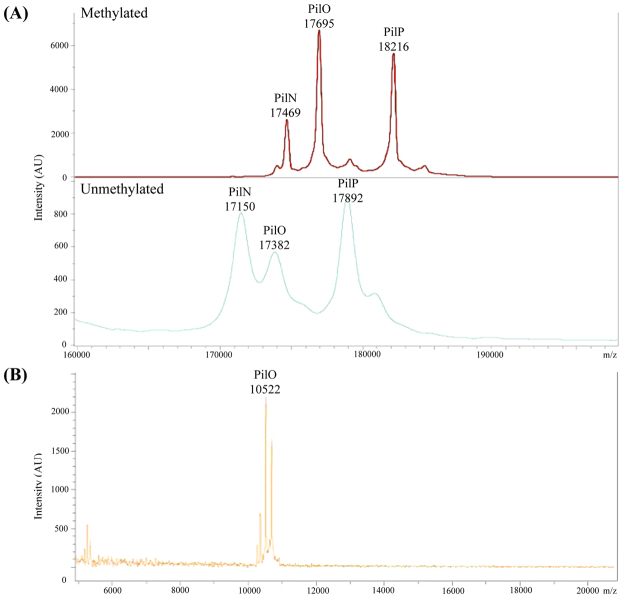

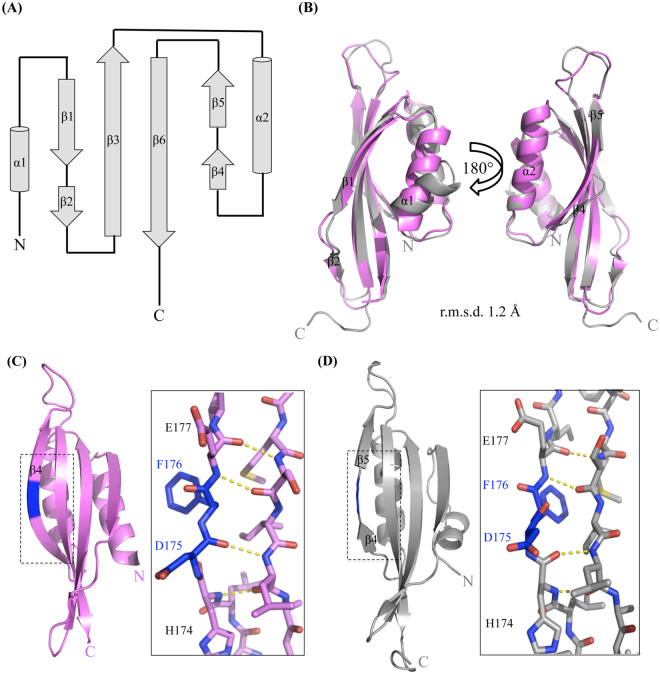

To better understand how PilN and PilO interact with one another and with PilP, we attempted to solve the structure of a stable, soluble heterotrimeric complex of PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ1817. Although the protein complex was soluble, abundant, and stable over long periods of time at various temperatures, crystallization was unsuccessful. To promote crystallization we explored the use of reductive methylation, thought to promote crystal formation through chemical modification of surface-exposed lysines to decrease surface entropy35. All three proteins were present after reductive methylation as determined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining, and methylation was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/TOF MS) (Fig. 1A). A small array of hexagonal pyramid shaped crystals were grown and data were collected at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) and processed using Imosfilm36. During the preliminary analysis of the data, it became evident that only one of the three proteins (PilO) was present in the crystal. Although the PilO construct used encompassed residues 52–208, we could model only residues 110–206. Analysis of the crystals using MALDI-TOF/TOF MS confirmed that proteolysis had occurred during the crystallization process (Fig. 1B). Various PilO fragments were present, with the largest peak corresponding to a PilO fragment with a molecular weight of 10,522 Da, similar to the predicted mass of 10,560 Da for a PilO 110–206 fragment (Fig. 1B). Using our previous 2.2 Å PilOΔ68 structure (PDB 2RJZ)30 as a template, a 1.7 Å structure of PilOΔ109 was solved by molecular replacement and refined to an Rwork/Rfree value of 23.1/26.7% (Table 1 and Fig. 2).The new structure (PDB 5UVR) encompasses residues P110 to K206, equivalent to ~60% of the periplasmic region (just under 50% of the total protein). PilOΔ109 has two αββ motifs composed of α1-β1β2-β3 and α2-β4β5-β6 (Fig. 2A). The four β-strands form an antiparallel β-sheet onto which the two α-helices pack. A pseudo-2-fold axis within the β-sheet relates the two compact αββ-subdomains with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) of 3.4 Å for 47 Cα atoms. The 2-residue linker between β1β2 includes P134 and E135, while the 2-residue linker between β4β5 contains D175 and F176; these residues are responsible for the observed strand discontinuity. To directly compare the new and previous structures, we truncated the latter to include only residues 110–206 (known henceforth as PilO2RJZΔ109). The two structures have an r.m.s.d. of 1.2 Å over 97 Cα backbone atoms (Fig. 2B). Compared to the previous structure, the N-terminal α1-helix in PilOΔ109 is shorter, with more of the surrounding region unstructured and tilted ~45° away from the β-sheet, which could be due to the loss of the N-terminal coiled-coil regions in the PilO2 structure, or to differences in the crystallization conditions (Fig. 2B – left). A second discontinuous β-strand (β4β5) – not present in the PilO2RJZΔ109 structure – was identified in the new structure (Fig. 2B – right). The main chain carbonyls of D175 and F176 do not participate in hydrogen bonding between the β4β5- and β6-strands in the PilOΔ109 structure, creating the discontinuous β-strand (Fig. 2D). In the previous PilO structure, hydrogen bonding was complete through this segment (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1.

Mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/TOF) results indicate successful methylation of the PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 complex but only PilO fragments were present in the crystals. (A) Methylated (top) and unmethylated (bottom) samples of 1 mg/mL PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 was analyzed on a Bruker UltrafleXtreme linear detector in positive ion mode. The change in the molecular weight of PilN, PilO and PilP between the methylated and unmethylated samples were 319 Da, 313 Da, and 324 Da, respectively. All three protein fragments have 11 lysine residues, which could be methylated. A single dimethyl-Lys group adds 28 Da. (B) Two crystals were washed and resuspended in buffer and was analyzed on a Bruker UltrafleXtreme linear detector in positive ion mode. This weight corresponds to a 110–206 fragment of PilO (approximate molecular weight of 10,560 Da). Remaining peaks–were confirmed to be various PilO fragments. The numbers above the peaks are the molecular weights shown in Da. The chromatogram shows the ion intensities (in arbitrary units) according to mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for PilOΔ109.

| Data Collection | |

|---|---|

| Beamline | CLS 08ID-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 |

| Space group | P6122 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 40.8, 40.8, 250.5 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 35.34-1.7 (1.79-1.7) |

| Total reflections | 263281 |

| Unique reflections | 14759 |

| Redundancy | 6.7 (6.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| Mean I/I) | 10.8 (2.9) |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.8 (54.2) |

| Anisotropic deltaB | 11.52 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.54 |

| Structure Refinement | |

| Rwork/free (%)* | 23.1/26.7 |

| R.m.s.d. Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| R.m.s.d. Bond angles (°) | 0.769 |

| Ramachandran plot‡ | |

| Total favoured (%) | 98 |

| Total allowed (%) | 2 |

| Coordinate error (Å)§ | 0.14 |

| Wilson B factor | 23.7 |

| Atoms | |

| No. protein atoms | 849 |

| No. water | 97 |

| Average B-factors (Å2)§ | |

| Protein | 40.58 |

| Water | 47.70 |

Note: Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell. *Rwork = ∑ | |Fobs| − k|Fcalc| |/|Fobs| where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. Rfree is the sum extended over a subset of reflections (5%) excluded from all stages of the refinement. ‡As calculated using MolProbity49. §Maximum-likelihood based Coordinate Error and Average B-factors, as determined by PHENIX42

Figure 2.

Comparison of P. aeruginosa PilO structures. (A) Topological diagram of PilOΔ109 mapping the N- (P110) and C-termini (K206). Helices α1 and α2 are 8 and 13 residues in length, respectively, while β3 and β6 are 12 residues long. Beta strands β1 and β2 are 8 and 3 residues in length, whereas β4 and β5 have 3 and 4 residues, respectively. (B) Comparison of the PilOΔ109 structure (grey; PDB 5UVR) with the equivalent residues (110–206) of PilO2RJZΔ109 (violet; PDB 2RJZ30). (C) Reverse view of the PilO2RJZΔ109 structure (violet), highlighting the β4 strand residues, D175 and F176 (blue), participating in hydrogen bonding with the β5 strand. (D) The equivalent region of the PilOΔ109 structure (grey) highlighting the second discontinuous β4β5-strand (inset) and the D175 and F176 residues (blue) not participating in hydrogen bonding with the β6 strand. Hydrogen bonding is indicated by the yellow dashed lines.

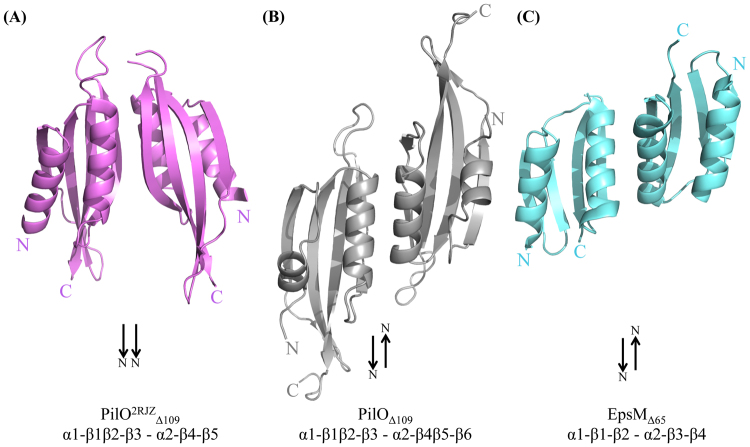

The interface for the predicted PilOΔ109 dimer is similar to that of EspM

One molecule of PilO Δ109 was found in the asymmetric unit. Using PISA software37, two possible interaction interfaces with crystallographic symmetry mates were identified, based on the protein-protein interactions in the crystal lattice. These interfaces bury 1,180 and 1,140 Å2, respectively, compared with a total surface area of approximately 11,500 Å2. The dimer with the largest buried surface area, considered to be more energetically favourable (-12 kcal/mol), was analyzed further (Fig. 3B). The interface between the core domains of PilO2RJZΔ109 was formed by interactions between the α2-helix of monomer 1 and the β4-strand of monomer 2 (Fig. 3A)30. These contacts are similar to the new structure of PilOΔ109, where the α2-helix and β4β5-strands are the main points of contact in the predicted dimerization interface. However due to the orientation of the individual monomers, the α2-helix of monomer 1 would interact with the α2-helix of monomer 2; similarly, the broken β4β5 strands of each monomer would interact. The monomer orientation in the PilOΔ109 dimer places the β-sheets on the same side, forming a longer 8-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet (Fig. 3B). This is in contrast to the PilO2RJZΔ109 dimer where the β-sheets and α-helices are on opposite sides (Fig. 3A). The PilOΔ109 interface resembles that reported for the 1.7 Å resolution structure of its homologue EpsMΔ65 from the V. cholerae T2SS, with the monomers arranged in the same antiparallel orientation (Fig. 3C)(PDB 1UV738). EpsMΔ65 has dimerization contacts between the α2-helices of each monomer and between the β3-strands, equivalent to β4β5 in the PilOΔ109 structure (Fig. 3B)38. This organization orients the N- and C-termini of the individual PilOΔ109 and EpsMΔ65 monomers in opposite directions, compared to the PilO2RJZΔ109 structure where the N- and C-termini are oriented in the same direction, which we believe to be the more physiologically relevant conformation (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

The interface of the predicted PilOΔ109 dimer is similar to that of EpsM. (A) The dimer interface found in the PilO2RJZΔ109 dimer (violet) (PDB 2RJZ30). (B) The most energetically favourable predicted interaction interface for the PilOΔ109 structure (grey). (C) The EpsMΔ65 crystal structure (cyan) from the T2SS of V. cholerae (PDB 1UV738). Black arrows indicate direction of the N-termini for each subunit.

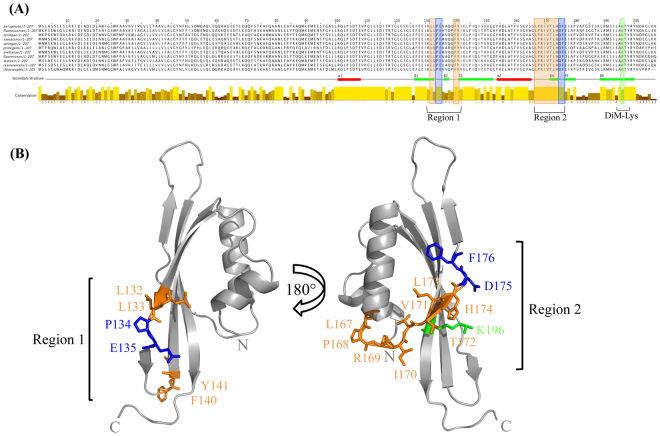

Two highly conserved hydrophobic segments correspond to unstructured loop regions

The PilMNOP subcomplex is highly conserved in Pseudomonads and other T4aP expressing bacteria6. Alignment of P. aeruginosa PilO with homologues from various Pseudomonads revealed a number of notable features (Fig. 4A). The N-terminal residues (1–99) share relatively limited overall sequence conservation, whereas the core domain, consisting of the two αββ motifs, is more highly conserved, especially in regions of defined secondary structure. The regions corresponding to α1 and α2 are highly conserved, as are the residues immediately following the α1-helix (109–116). In our previous structure, these were part of the longer α1-helix, but in the new PilOΔ109 model, they are unstructured (Fig. 2). The β-strands are also relatively conserved, but interestingly, there is a high degree of conservation in two largely hydrophobic regions, corresponding to the unstructured areas surrounding the discontinuous β2β3- and β4β5-strands. In the new structure, a dimethyl-Lys residue (K196) was identified on the back face of the β6-strand (Fig. 4B), the result of the reductive methylation used to promote crystallization of the PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 complex (Fig. 1A). The PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 fragments are each predicted to have 11 lysine residues potentially available for methylation. The difference in size for each protein post-methylation (PilN 319 Da, PilO 313 Da, and PilP 324 Da), suggested that ~10 lysine residues each (28 Da per lysine), plus an additional 28 Da for the N terminus of each protein, were modified. However, only K196 could be modelled, while the remaining lysines (K131, K179, K188, K203, and K206) were missing electron density. Although this meant we could not confirm structurally that these other residues were dimethylated, the mass spectrometry results were consistent with this modification. Region 1 includes residues L132, L133, F140, Y141, plus “β-strand breaker” residues P134 and E135 (Fig. 4B - left). Region 2, on the opposite side of the PilOΔ109 model, consists of residues L167, P168, R169, I170, V171, T172, L173, H174, and the β-strand breaker residues D175 and F176 (Fig. 4B - right). The LPRIVTL residues (167–173) in region 2 were previously identified as the most highly conserved segment in PilO30. Unstructured regions of proteins can often undergo conformational changes to a more ordered state upon interaction with their target substrates – including other proteins39. With this information, we hypothesized that these highly conserved residues found in largely unstructured regions could play a potential role in protein-protein self interactions (homodimers) or with PilN and/or PilP. The residues in this region were mutated (individually or in pairs; Table 2) by introducing point mutations onto the P. aeruginosa chromosome at the pilO locus to preserve the native stoichiometry and expression levels that are important for T4aP function33.

Figure 4.

Highly conserved residues in unstructured regions on the PilOΔ109 structure probed by site directed mutagenesis. (A) The sequence conservation of the PilO families from a subset of Pseudomonads (P. fluorescens, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448 A, P. savastanoi, P. syringae, P. protegens CHA0, P. avellanae, P. stutzeri A1501, P. resinovorans, P. chlororaphis) are indicated by the bars. The conservation of the residues is indicated by the bar and the intensity of the color (high conservation, high bar and bright yellow; low conservation, low bar and a dark brown color). The α-helices (red rectangles) and β-strands (green arrows) indicate secondary structure elements present in the PilOΔ109 structure. (B) The structure of PilOΔ109 indicating the position of the residues chosen for site directed mutagenesis. Conserved and unstructured residues (orange), β-strand breakers (blue), and the position of the di-methyl Lys (green), are indicated.

Table 2.

Summary of PilO mutants and their phenotypes.

| PilO | Location | Twitching motility | Surface pili |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL132-133AA | Region 1 – β1 | Yes | Yes |

| PE134-135AL | Region 1 – β1 | Yes | Yes |

| F140A | Region 1 – β2–β3 | Yes | Yes |

| Y141A | Region 1 – β2-β3 | Yes | Yes |

| L167A | Region 2 – α2-β4 | Yes | Yes |

| P168A | Region 2 – α2-β4 | Yes | Yes |

| R169D | Region 2 – α2-β4 | Reduced (≈ 40%) | Reduced (≈ 65%) |

| I170A | Region 2 – α2-β4 | Reduced (≈ 50%) | Reduced (≈ 70%) |

| V171A | Region 2 – α2-β4 | Yes | Yes |

| TL172-173AA | Region 2 – β4 | Yes | Yes |

| H174A | Region 2 – β4 | Yes | Yes |

| D175R | Region 2 – β4-β5 | Yes | Yes |

| F176A | Region 2 – β4-β5 | Yes | Yes |

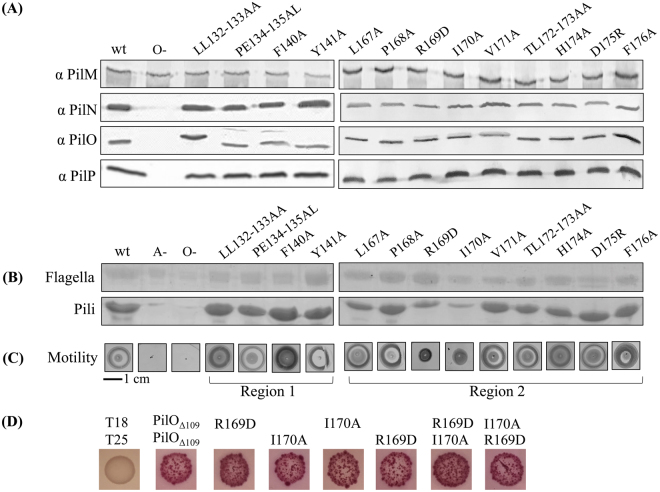

Substitutions designed to disrupt hydrophobic or charged interactions were made (Table 2). Because PilO stability affects that of its protein partners33, stable expression of all alignment subcomplex proteins was verified by Western blot using protein-specific antisera (Fig. 5A). Mutants were then assessed for surface pilus expression and twitching motility. Only PilO R169D and I170A reduced twitching motility (approx. 40% and 50% relative to wild-type, respectively) and levels of surface piliation (Figure 5BC). Although lacking the N-terminal residues (68–109) of the previous PilO2RJZ structure, the PilOΔ109 core regions interacted in a bacterial two hydrid system40. Introduction of either the R169D and/or the I170A substitutions did not disrupt PilO homodimerization (Fig. 5D), suggesting the loss of function could be due to perturbation of interactions with other partners.

Figure 5.

PilO R169D and I170A mutations disrupt T4aP function. All PilO mutant strains, as well as wild-type (wt) and the negative control (O−), were tested for (A) expression and stability of alignment subcomplex proteins (PilMNOP) via Western blotting using protein specific antisera as indicated on left, (B) sheared surface pili, and (C) twitching motility. Sheared surface proteins were separated on 15% SDS-PA gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to visualize. For reference, originals of the Western blots and gels are provided in Supplementary Figure S1. Twitching zones were stained with 1% (w/v) crystal violet. A non-piliated strain of P. aeruginosa (A-) was included, though some spill over from the wt lane can be detected. (D) Interaction between T18-PilOΔ109 and T25-PilOΔ109 fusion constructs were detected using a bacterial two hybrid assay, on MacConkey agar indicating media supplemented with 1% maltose. Interaction between the core regions of PilO remained despite the presence of either the R169D and/or I170A mutations.

Discussion

Visualizing interfaces among components of the T4aP alignment subcomplex through co-crystallization of a heterotrimeric PilNOP complex has proven to be a challenging goal. Although the soluble, stable complex was used for the crystallization experiments, the resulting crystals contained only a truncated form of PilO (PilOΔ109). We suspect that the high pH of CAPS in the crystallization condition, or the prolonged period required for the formation of crystals (6 months), may have led to dissociation of the PilNOP complex, leaving only the core αββ domain of PilO intact. Similar phenomena have been observed for other PilN and PilO homologs, where constructs that initially included the predicted coiled-coils and the αββ core ultimately formed crystals containing only the core region, indicating that it is highly stable to proteolytic degradation31,38. Coupling work from our previous study16 wherein the N-terminal region of PilP (~18–76) interacts with a PilNO heterodimer, with new information from cryoelectron tomography studies34, we now infer that it is mainly the unstructured N-terminal region of PilP interacts with PilNO. Thus, inclusion of the full length PilP protein in the soluble PilNOP complex and mobility of its C-terminal folded domain due to lack of interaction with PilNO may have impeded crystal formation; future work will address this issue.

Though shorter than our previous structure (PDB 2RJZ)30, PilOΔ109 is of higher resolution and thus provided a new level of structural detail. The αββ fold, a simplified version of the ferredoxin fold (βαβ), was first identified in EpsM from the Vibrio cholerae type II secretion system (T2SS), and is typical of PilN and PilO homologues30,38,41. Previously, only one discontinuous β-strand was identified in the first αββ motif (Fig. 2C), but the new structure exhibits another β-strand break in the second αββ motif at the same position, resulting in a secondary structure pattern of α1-β1β2-β3 and α2-β4β5-β6 (Fig. 2D). Both discontinuous β-strands are found on the outside edges of the antiparallel β-sheet where they may increase flexibility to accommodate multiple protein-protein interactions, such as recently described PilO homo- and PilNO heterodimers32.

Two potential interaction interfaces with crystallographic symmetry mates were investigated37. Interestingly, the more energetically favourable interface orients the N- and C-termini of each PilO monomer in opposite directions (Fig. 3B), similar to the interface identified in the T2SS PilO orthologue, EpsM, which crystallized as a homodimer (Fig. 3C) (PDB 1UV7)38. For these head-to-tail oriented dimers to be biologically relevant, the PilO and EpsM proteins would have to interact horizontally (parallel to the plane of the membrane rather than vertically as portrayed in Fig. 3B), such that their N- and C-termini would be oriented to the sides to accommodate the membrane anchoring of their transmembrane segments. Instead, it is more likely that the previously observed PilOΔ68 dimer interface (Fig. 3A) – in which both N- and C-termini are oriented in the same direction, towards the inner membrane – is the biologically relevant one, similar to the orientation described in a recent cryoelectron tomographic model of the T4aP system of M. xanthus34.

A large proportion of highly conserved PilO residues are located in regions that lack regular secondary structure (Fig. 4). Of these, only R169D and I170A mutations had effects on piliation and motility (Fig. 5B,C). These residues are found in the unstructured region between the α2-helix and the β4-strand (region 2), previously identified as the most highly conserved motif in PilO orthologues30. This region of PilO also participates in both homodimerization and formation of PilNO heterodimers15,30,32. These residues cluster near the discontinuous β–strands, a feature not observed in the PilO2RJZΔ109 structure (Fig. 2)30. The role of these discontinuous β-strands has yet to be determined, as other PilO or PilN homologs appear to have a single, continuous β-strand at the corresponding position31,38,41. Split β-strands could afford these regions of PilO more flexibility to accommodate dynamic interactions with other periplasmic T4aP components. However, replacing the “β-strand breaker” residues (P134 and E135 in region 1, or D175 and F176 in region 2) had no effect on T4aP function. PilO homodimerization was unaffected by the R169D and I170A residues as determined using a bacterial two-hybrid assay (Fig. 5D). Whether these residues affect PilO interaction with PilN or PilP is currently under investigation.

In conclusion, we determined a higher-resolution structure of the PilO core domain, revealing new features including a second discontinuous β-strand. Two residues in close proximity to this feature are critical for normal T4aP function. High-resolution structures are useful tools when combined with other structural techniques, such as cryo-electron microscopy or small angle X-ray scattering. For example, atomic structures from the T4aP and T2S systems of various bacterial species were used to model each of the T4aP components in a ~4 nm electron cryo-tomographic envelope of the T4aP system of M. xanthus, for which no structures are available34. Comparison of models of the piliated and non-piliated states of the T4aP system allowed for insights into the mechanism behind T4aP function34. These findings provide a stepping-stone for further investigation of the interactions between the highly conserved alignment subcomplex proteins.

Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. E. coli and P. aeruginosa were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) media supplemented with antibiotics at the following final concentrations when necessary (μg/mL): ampicillin (Ap), 100; kanamycin (Kn), 50; gentamicin (Gm), 15 for E. coli and 30 for P. aeruginosa, unless otherwise specified. Plasmids were transformed by heat shock into chemically competent cells. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (MOBIX – McMaster University).

Expression and purification of PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18

N-terminally truncated versions of PilN and PilO were previously cloned into the EcoRI/HindIII and NdeI/XhoI cloning sites, respectively, of a pET28a vector, creating untagged but co-expressed PilNΔ44/PilOΔ5117,30. TOPO cloning was used to introduce an N-terminally truncated form of PilP into a pET151 vector (Invitrogen), creating a PilPΔ18 construct with an N-terminal 6-His tag (PilPΔ18_His). Based on previous optimization studies, we expressed the PilNO and PilP fragments separately, combining the bacterial pellets at the purification stage. Briefly, the constructs were transformed separately into E. coli BL21 cells and plated on LB agar plates supplemented with either Km (for the pET28a vector) or Ap (for the pET151 vector). A single colony of each transformant was used to inoculate separate 20 mL aliquots of LB containing appropriate antibiotics, and incubated overnight at 37 °C, shaking at 200 rpm. Each overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 L of fresh LB (1:100 dilution) containing antibiotic and the cells were grown at 37 °C, with shaking, to an OD600 of approximately 0.6. Protein expression was induced by adding IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1 thiogalactopyranoside, Sigma Aldrich) to the cultures at a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, prior to being harvested by centrifugation (3,993 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) in an Avanti J-26 XPI centrifuge (Beckman Coulter). Bacterial pellets were frozen at −80 °C until further use.

Bacterial pellets were thawed, each resuspended in 10 mL Nickel A buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol), then both pellets (PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51 and PilPΔ18_His) were combined into a single 50 mL screw cap tube with 1 complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche). Cells were lysed via sonication on ice, on setting 4, for 2 min with cycles of 10 s on and 10 s off (Sonicator 3000; Misonix). The lysates were centrifuged (11,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) in an Avanti J-26 XPI centrifuge (Beckman Coulter) to remove intact cells and other cellular debris. Pelleted material was retained for analysis by SDS-PAGE, while supernatants were filtered through 0.22 μm Acrodisc syringe filter (Pall Corporation). The lysate was purified using Nickel-NTA affinity chromatography on an AKTA start FPLC (VWR). Protein lysate was flowed through a 1 mL His-TrapTM FF column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer, and washed with Nickel A buffer, then increasing amounts of Nickel B buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 300 mM imidizole, 10% (v/v) glycerol) in a linear gradient. The bound protein was eluted from the column in pure Nickel B buffer and collected in 1 mL fractions. An aliquot of each fraction was mixed 1:1 with 2 × reducing or non-reducing SDS-PAGE loading and electrophoresed on a 15% SDS-PA gel. The gel was stained using Coomassie Blue Staining solution (0.1% (w/v) Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, 50% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) glacial acetic acid), or developed by Western blot using protein-specific antisera as described below. His-tagged PilPΔ18 was successfully able to pull out untagged PilNΔ44 and PilOΔ51 as previously described17.

TEV Digestion

The PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18_His protein complex elution fraction, plus 500 μL of 1 mg/mL of Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease were added to a 12–30 mL Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassettes 10 K MWCO (Thermo Scientific). The cassette and its contents were dialyzed into a new buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl) overnight at 4 °C, stirring. The sample was extracted from the cassette and run through a 1 mL His-TrapTM FF column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with the dialysis buffer to separate PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 complex from His-tag. Flow through from the column was collected and the protein complex was concentrated down using a Vivaspin-20 10 kDa centrifugal concentrator (GE Healthcare) in an Allegra X-14 (Beckman Coulter) benchtop centrifuge (3,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) to concentrate the protein complex. A Bradford assay was used to measure the final protein concentration of the complex at approximately 10 mg/mL.

Reductive Methylation

Modification of surface-exposed lysine residues on the PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 complex was carried out using the Hampton Research Reductive Alkylation kit protocol following manufacturer’s instructions (Hampton Research). Briefly, 20 μL of 1 M dimethylamine borane complex (ABC) was added to 1 mL of 10 mg/mL protein, and inverted to mix. Then 40 μL of 1 M formaldehyde was added to the tube, and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C rocking. After the 2 h incubation, another 20 μL of ABC was added to the tube followed by another 40 μL of 1 M formaldehyde. The tube was incubated again at 4 °C for 2 h. Finally 10 μL of ABC was added to the tube and the reaction incubated overnight at 4 °C with rocking. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 125 μL of 1 M glycine, and incubated for 2 h, rocking at 4 °C. The methylated protein complex was then separated from the reaction products through size exclusion chromatography.

Size exclusion chromatography of the PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 subcomplex

Analytical gel filtration of the methylated PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 protein complex was performed using an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Superdex S75 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) column. The column was pre-equilibrated with a 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 120 mM NaCl buffer prior to injection of the protein sample. Typically, 500 μL of a 10 mg/mL protein solution was loaded onto the column. Gel filtrations were run at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min onto the S75 column at 4 °C, and fractions were collected in a 96-well plate format, with the absorbance at 280 nm monitored over the course of the experiment. The purest PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 protein fractions, as determined by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue, were pooled and concentrated down using a Vivaspin 2 (10 kDa) centrifugal concentrator (GE Healthcare) in an Allegra X-14 (Beckman Coulter) benchtop centrifuge (3,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C).

Crystallization and structural determination

Native PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapour diffusion method in a 1:1 ratio of protein (12 mg/mL in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 120 mM NaCl) to precipitant (0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (CAPS) pH 10.5, 20% (v/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000) with the addition of 0.2 μL of 30% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) over 1.5 M ammonium sulphate, and kept at 4 °C for approximately 6 months, with trays being checked each week for the first 2 months, then on a monthly basis. Data was collected at 0.979 Å on the 08ID-1 beamline at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) in Saskatchewan, Canada. Data was processed using IMosflm36 and the space group was determined to be P6122. The structure of PilO was determined by molecular replacement with Phaser-MR from Phenix42 using a truncated model of PilOΔ68 (PDB 2RJZ30) as the search model. Iterative rounds of model building and refinement was carried out using Coot43 and Phenix-Refine42. During the structure solution, it became clear that only one protein (PilO) was present in the crystal. The PilO protein could be modelled from residue 110 to the C terminus (PilOΔ109). The data collection and model refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. Root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d) values between the superimposed structures, and graphical presentation were both performed in PyMOL (v 1.8; Schrodinger).

Mass Spectrometry of the PilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 complex

Methylated and unmethylated samples of 1 mg/mLPilNΔ44/PilOΔ51/PilPΔ18 in a 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 120 mM NaCl buffer were sent to the Biointerfaces Institute (McMaster University) for analysis. Briefly, the sample was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a saturated solution of sinapinic acid prepared in a 30:70 (v/v) Acetonitrile:TFA 0.1% in water. One μL of the samples was spotted on a MALDI pad and subject to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) on a Bruker UltrafleXtreme linear detector in positive ion mode to determine the mass to charge ratio of the proteins. For analysis of the crystals by mass spectrometry, 2 crystals were washed in the initial buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 120 mM NaCl), then a 0.1% (v/v) acetonitrile solution. The crystals were dissolved in 15 μL of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 100 mM NaCl buffer and sent to the Biointerfaces Institute (McMaster University) for analysis.

PilO bioinformatics analysis

The P. aeruginosa PAK PilO sequence was retrieved from the Pseudomonas Genome Database44 and was aligned using Jalview 2.8.245,46 with a subset of Pseudomonads (P. fluorescens, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448 A, P. savastanoi, P. syringae, P. protegens CHA0, P. avellanae, P. stutzeri A1501, P. resinovorans, P. chlororaphis). The mapped secondary structure elements are based on the new PilOΔ109 structure described herein. Generation of PilO mutants.

Sites for the introduction of single or double point mutations in PilO were chosen with reference to the new PilO∆109 structure (below). To maintain native stoichiometry and expression levels, mutations of interest were introduced onto the P. aeruginosa chromosome at the native pilO locus. First, codons for PilO residue substitutions were introduced into a pEX18Gm::pilNOP construct using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genes and mutations were sequenced (MOBIX) to verify their identity. Next, pilO mutants were constructed using a Flp-FRT (FLP recombination target) system as previously described47. Briefly, the suicide vectors containing the mutant pilO gene plus the flanking genes (pilN and pilP) to provide homologous regions for recombination were introduced into E. coli SM10 cells. The constructs were transferred by conjugation in a 1:9 ratio of P. aeruginosa to E. coli. The mixed culture was pelleted for 3 min at 2292 × g in a microcentrifuge, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 μL of LB, spot-plated on LB agar, and incubated overnight at 37 °C. A P. aeruginosa PAK strain which contained a pilO::FRT mutation33 was used as a recipient for the pEX18Gm::pilNOP constructs in mating experiments. After mating, cells were scraped from the LB agar plate, resuspended in 1 mL of LB and the E. coli SM10 donor was counterselected by plating on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA; Difco) containing Gm (100 μg/mL). Gm-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates were streaked on LB no salt plates with sucrose (1% (w/v) bacto-tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) bacto-yeast extract, 5% (w/v) sucrose) then incubated for 16 h at 30 °C. Select colonies were cultured in parallel on LB and LB plates supplemented with Gm. Gm-sensitive colonies were screened by PCR using pilO primers to confirm replacement of the FRT-disrupted gene, and PCR products of the expected size were sequenced to confirm incorporation of the desired mutations.

Twitching motility assays

Twitching assays were performed as previously described48. Briefly, single colonies were stab inoculated to the bottom of a 1% LB agar plate. The plates were incubated for 36 h at 37 °C. Post incubation, the agar was carefully removed and the adherent bacteria stained with 1% (w/v) crystal violet dye, followed by washing with tap water to remove unbound dye. Areas of the twitching zones were measured using ImageJ software (NIH). All experiments were performed in triplicate with at least three independent replicates.

Sheared surface protein preparation

Surface pili and flagella were analyzed as described previously48. Briefly, the strains of interest were streaked in a grid-like pattern on LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for ~16 h. The cells were scraped from the plates with glass coverslips and resuspended in 4.5 mL of PBS. Surface proteins were sheared by vortexing the cell suspensions for 30 s. Cells were transferred to three separate 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and pelleted by centrifugation at 11,688 × g for 5 min. Supernatant was transferred to fresh tubes and centrifuged at 11,688 × g for 20 min to remove remaining cells. Supernatants were transferred to new tubes and surface proteins were precipitated by adding 1/10 volume of 5 M NaCl and 30% (w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG 8000, Sigma Aldrich) to each tube and incubating on ice for 90 min. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 11,688 × g, resuspended in 150 μL of 1× SDS sample buffer (125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS and 0.001% bromophenol blue). Samples were boiled for 10 min and separated on 15% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Preparation of whole cell lysates

P. aeruginosa strains were grown on LB agar plates overnight at 37 °C. Cells were scraped from the surface and resuspended in 1 × PBS to an OD600 of 0.6. A 1 mL aliquot of cells was collected by centrifugation at 2292 × g for 3 min in a microcentrifuge. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of 1× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. Whole cell lysate samples were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE gels and subject to Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysate samples were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 1 h at 225 mA. Membranes were blocked using a 5% (w/v) low fat skim milk powder in 1 × PBS for 1 h at room temperature on a shaking platform, followed by incubation with the appropriate antisera for 2 h at room temperature, at a dilutions as follows: PilM 1/2500, and PilNOP 1/1000 each. The membranes were washed twice in 1× PBS for 5 min then incubated in goat-anti-rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1/3000 for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed twice in 1× PBS for 5 min, and visualized with alkaline phosphatase developing reagent (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bacterial Two-Hybrid Assay

Chemically competent E. coli BTH101 cells were co-transformed with various combinations of pUT18C and pKT25 protein fusions, and tested for interaction using MacConkey agar supplemented with activity using a 96-well plate-based assay as previously described40 with modifications. Briefly, BTH101 cells co-transformed with T18-PilOΔ109 and T25- PilOΔ109 fusion constructs with either the R169D or I170A mutations as indicated. Cells were grown at 30 °C in LB supplemented with Ap and Kn, shaking at 200 rpm overnight. LB broth containing antibiotics and 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalacto-pyranoside (IPTG; Sigma-Aldrich), were inoculated with a 1:5 dilution of an overnight culture and grown at 30 °C, 260 rpm shaking, to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ~0.6 and standardized. Cells were spotted on MacConkey agar supplemented 1% maltose, and plates were incubated for 48 h at 30 °C.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Operating Grant MOP-93585 to L.L.B and P.L.H. P.L.H. is the recipient of a Tier I Canada Research Chair.

Author Contributions

T.L.L. and L.L.B. designed the study, and T.L.L., L.L.B. and P.L.H. wrote the paper. Protein was expressed, purified, and crystallized by T.L.L. M.C.M. and M.S.J. determined the X-ray crystal structure. T.L.L. designed and constructed mutants, and analyzed PilO function. All authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20925-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

P. L. Howell, Email: howell@sickkids.ca

L. L. Burrows, Email: burrowl@mcmaster.ca

References

- 1.Bradley DE. A function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO polar pili: twitching motility. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1980;26:146–154. doi: 10.1139/m80-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrows LL. Weapons of mass retraction. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;57:878–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrows LL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility: type IV pili in action. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2012;66:493–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattick JS. Type IV pili and twitching motility. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2002;56:289–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Molecular Microbiology. 1998;30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelicic V. Type IV pili: e pluribus unum? Molecular Microbiology. 2008;68:827–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govan JR, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiological Reviews. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn HP. The type-4 pilus is the major virulence-associated adhesin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa–a review. Gene. 1997;192:99–108. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heiniger RW, Winther-Larsen HC, Pickles RJ, Koomey M, Wolfgang MC. Infection of human mucosal tissue by Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires sequential and mutually dependent virulence factors and a novel pilus-associated adhesin. Cellular Microbiology. 2010;12:1158–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skerker JM, Berg HC. Direct observation of extension and retraction of type IV pili. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:6901–6904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121171698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koo J, et al. PilF is an outer membrane lipoprotein required for multimerization and localization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IV pilus secretin. Journal of Bacteriology. 2008;190:6961–6969. doi: 10.1128/JB.00996-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo J, Lamers RP, Rubinstein JL, Burrows LL, Howell PL. Structure of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IVa Pilus Secretin at 7.4 A. Structure. 2016;24:1778–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takhar HK, Kemp K, Kim M, Howell PL, Burrows LL. The platform protein is essential for type IV pilus biogenesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:9721–9728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.453506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang P, Habash M, Burrows LL. Disparate subcellular localization patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IV pilus ATPases involved in twitching motility. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187:829–839. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.829-839.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leighton TL, Dayalani N, Sampaleanu LM, Howell PL, Burrows LL. A novel role for PilNO in type IV pilus retraction revealed by alignment subcomplex mutations. Journal of Bacteriology. 2015;197:2229–2238. doi: 10.1128/JB.00220-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tammam S, et al. PilMNOPQ from the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus system form a transenvelope protein interaction network that interacts with PilA. Journal of Bacteriology. 2013;195:2126–2135. doi: 10.1128/JB.00032-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tammam S, et al. Characterization of the PilN, PilO and PilP type IVa pilus subcomplex. Molecular Microbiology. 2011;82:1496–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig L, Pique ME, Tainer JA. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat.Rev.Microbiol. 2004;2:363–378. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen Y, Jackson SG, Aidoo F, Junop M, Burrows LL. Structural characterization of novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;395:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen Y, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa minor pilins prime type IVa pilus assembly and promote surface display of the PilY1 adhesin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:601–611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen Y, et al. Structural and functional studies of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa minor pilin, PilE. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:26856–26865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.683334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beatson SA, Whitchurch CB, Sargent JL, Levesque RC, Mattick JS. Differential regulation of twitching motility and elastase production by Vfr in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184:3605–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3605-3613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darzins A. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene cluster involved in pilus biosynthesis and twitching motility: sequence similarity to the chemotaxis proteins of enterics and the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus. Molecular Microbiology. 1994;11:137–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leighton TL, Buensuceso R, Howell PL, Burrows LL. Biogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pili and regulation of their function. Environmental Microbiology. 2015;17:4148–4163. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strom MS, Lory S. Structure-function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annual Review of Microbiology. 1993;47:565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin PR, Watson AA, McCaul TF, Mattick JS. Characterization of a five-gene cluster required for the biogenesis of type 4 fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Molecular Microbiology. 1995;16:497–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayers M, Howell PL, Burrows LL. Architecture of the type II secretion and type IV pilus machineries. Future Microbiology. 2010;5:1203–1218. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karuppiah V. & Derrick, J. P. Structure of the PilM-PilN inner membrane type IV pilus biogenesis complex from Thermus thermophilus. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:24434–24442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.243535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCallum M, et al. PilN binding modulates the structure and binding partners of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IVa Pilus protein PilM. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016;291:11003–11015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.718353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampaleanu LM, et al. Periplasmic domains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PilN and PilO form a stable heterodimeric complex. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;394:143–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karuppiah V, Collins RF, Thistlethwaite A, Gao Y. & Derrick, J. P. Structure and assembly of an inner membrane platform for initiation of type IV pilus biogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E4638–4647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312313110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leighton TL, Yong DH, Howell PL, Burrows LL. Type IV Pilus Alignment Subcomplex Components PilN and PilO Form Homo- and Heterodimers In Vivo. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016;291:19923–19938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.738377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayers M, et al. PilM/N/O/P proteins form an inner membrane complex that affects the stability of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus secretin. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;394:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang YW, et al. Architecture of the type IVa pilus machine. Science. 2016;351:aad2001. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walter TS, et al. Lysine methylation as a routine rescue strategy for protein crystallization. Structure. 2006;14:1617–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abendroth J, Rice AE, McLuskey K, Bagdasarian M, Hol WG. The crystal structure of the periplasmic domain of the type II secretion system protein EpsM from Vibrio cholerae: the simplest version of the ferredoxin fold. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;338:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Battesti A, Bouveret E. The bacterial two-hybrid system based on adenylate cyclase reconstitution in Escherichia coli. Methods. 2012;58:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abendroth J, Kreger AC, Hol WG. The dimer formed by the periplasmic domain of EpsL from the Type 2 Secretion System of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Journal of Structural Biology. 2009;168:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winsor GL, et al. Pseudomonas Genome Database: improved comparative analysis and population genomics capability for Pseudomonas genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:D596–600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kus JV, Tullis E, Cvitkovitch DG, Burrows LL. Significant differences in type IV pilin allele distribution among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis (CF) versus non-CF patients. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2004;150:1315–1326. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.