Abstract

Perovskite light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are attracting great attention due to their efficient and narrow emission. Quasi-two-dimensional perovskites with Ruddlesden–Popper-type layered structures can enlarge exciton binding energy and confine charge carriers and are considered good candidate materials for efficient LEDs. However, these materials usually contain a mixture of phases and the phase impurity could cause low emission efficiency. In addition, converting three-dimensional into quasi-two-dimensional perovskite introduces more defects on the surface or at the grain boundaries due to the reduction of crystal sizes. Both factors limit the emission efficiency of LEDs. Here, firstly, through composition and phase engineering, optimal quasi-two-dimensional perovskites are selected. Secondly, surface passivation is carried out by coating organic small molecule trioctylphosphine oxide on the perovskite thin film surface. Accordingly, green LEDs based on quasi-two-dimensional perovskite reach a current efficiency of 62.4 cd A−1 and external quantum efficiency of 14.36%.

Solution-processable halide perovskites have high luminous efficiency and excellent chemical tunability, making them ideal candidates for light-emitting diodes. Here Yang et al. achieve high external quantum efficiency of 14% in the devices by fine-tuning the phase and passivating the surface defects.

Introduction

Solution-processed halide perovskite semiconductor materials show good photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs)1–7, which motivates applications in displays and lighting8. The perovskite light-emitting diodes (PeLEDs) have been reported with moderate electroluminescence (EL) efficiencies as well9–15. Their external quantum efficiencies (EQEs) have reached about 10% for near-infrared13–15 and also in green emission11,12,15. Hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites are better known for their free charge carriers with long diffusion length, which is good for solar cells. However, opposite properties are desired when they are used as emitting materials in LEDs11,16–18. The idea is to spatially confine charges with the insulating layers, and thus the exciton dissociation is suppressed and the radiative recombination can be enhanced in the perovskite films. Several efficient methods have been adopted, including polymer composite19, nanocrystal pinning11 and quantum dots3–7.

The exciton binding energy is enlarged in the two-dimensional (2D) perovskite and thus the emission efficiency can be enhanced20,21. In the early reports, 2D perovskite materials were used as emitting layers, while electroluminescence can only be observed at liquid nitrogen temperature20. Recently, quasi-two-dimensional (quasi-2D) perovskites have been proposed by doping 2D perovskites into three-dimensional (3D) perovskite structures. The initial idea was to enhance the humidity stability of perovskite solar cells22–24. More recently, it was found that multiple quantum wells could be assembled in these quasi-2D perovskites13,14, which can facilitate the formation of exciton and reduce the possibility of exciton dissociation. This makes the quasi-2D perovskite an efficient luminescent material13–15,25. The working mechanism of quasi-2D PeLEDs has been fully discussed elsewhere13,14. Electrons and holes injected from large bandgap phases (small n-phase) can rapidly transfer into small bandgap phases (large n-phase), then electrons and holes recombine in large n-phase and emit as photons. The EQEs of quasi-2D perovskite LEDs have achieved around 10%13,14 and highest EQE of 11.7% in near-infrared region was obtained14. Comparing to organic or inorganic LED counterparts26,27, there is still room for improvement in the EQE.

It is known that quasi-2D perovskite materials usually contain a mixture of phases and the phase impurity could lead to low emission efficiency, and thus fine control of the composition/phases is critical for efficient emission. In addition, solution processed thin films of quasi-2D perovskite show reduced crystal size compared to those of 3D perovskite13,15. This could increase the concentration of the defects and traps on the film surface and grain boundaries, which will act as non-radiative recombination centers and thus decrease the emission efficiency. Surface passivation has been proved an efficient way for reducing the defects in perovskite solar cells28–30.

In this article, PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 1, 2, …, ∞) is investigated as the emitting layer for quasi-2D perovskite LEDs, where PEA and FA are phenylethylammonium (C6H5C2H4NH3+) and formamidinium (HC(NH2)2+), respectively. Firstly, we optimize the films phase engineering/phase engineering. We find that the perovskite with n = 3 composition shows decent phases and the obtained films show the highest photoluminescence (PL) yield. Secondly, we present surface passivation of quasi-2D perovskite films by trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) treatment31. Accordingly, the PeLEDs based on PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 with n = 3 composition show green emission with current efficiency (CE) of 62.4 cd A−1 and EQE of 14.36%, which is the highest efficiency for PeLEDs reported so far.

Results

Properties of quasi-2D perovskite with different compositions

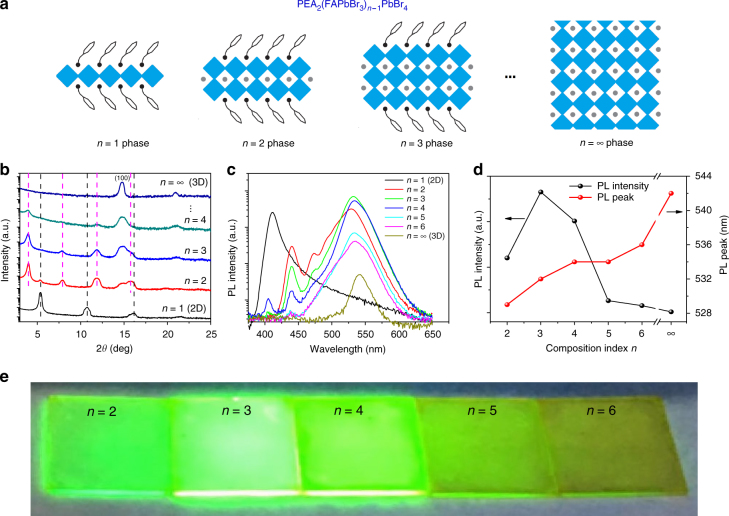

The schematics of n-phase PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 are drawn in Fig.1a, illustrating that the n-phase unit cell contains n-1 sheets of PbBr6-octahedra and two PEA tiers. The perovskite films are prepared by spin-coating a precursor solution using a crystal-pinning process11,32. Their compositions are controlled by the ratio PEABr:FABr:PbBr2 (Supplementary Table 1), and compositions n ranging from 2 to 6 are discussed. Previous results suggested that the quasi-2D perovskite films are not a single phase but contain a variety of n-phases13,14. For example, if the precursor solution with n = 2 composition is spin-coated, the generated films might include n = 2 phase but could also contain other phases such as n = 1 or n ≥ 3. To avoid misunderstanding, we distinguish the composition and phase by n-composition and n-phase, respectively. Methylammonium chloride (MACl) is also added into the precursor to improve the morphology and enhance the emission efficiency of the formed films (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2 and 12), but most MACl escape from the film during annealing33. The role of MACl has been well investigated in solar cells33,34. First, the MACl can slow down perovskite crystallization and improve film morphology. Second, the incorporation of a very small amount of elemental Cl could passivate the grain boundary, and then enhance the emission efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Properties of perovskite films with different compositions. a Scheme of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 phases. The black part is PEA, the blue square is PbBr6-octahedron and the gray dot is FA. b X-ray diffraction patterns of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 films with different n-compositions. Diffraction patterns of n = 1 phase (black vertical lines), n = 2 phase (pink vertical lines) and n = ∞ phase (marked with (100)) were labeled. The analysis details can be found in the Supplementary Table 2. c Photoluminescence of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 with different n-compositions. d Photoluminescence intensity and peak of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 films with different compositions with the data collected from c. e Photoluminescence image of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 films with different compositions under ultraviolet lamp excitation. Figure 1a adapted from ref. 13 (copyright 2016 Macmillan Publishers)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements are carried out to determine the accurate phases in our obtained quasi-2D perovskite films. As shown in Fig. 1b, all the perovskite films with n ≥ 2 compositions show diffraction peaks at 14.8°, which is the same as the (100) diffraction patterns of the 3D perovskite FAPbBr3 (refs. 7,35). However, the peaks become much more broadened, indicating that the diffraction peak could be from a series of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 phases with large n (n→∞) or 3D FAPbBr3 with nano-size grains (Supplementary Fig.3)15. This result shows that all the quasi-2D perovskite films always contain large n-phases (n→∞) or 3D perovskite regardless of the composition of the precursor. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images confirm the reduction of the crystal size during the transformation of 3D perovskite into quasi-2D perovskites (Supplementary Fig.3).

In addition to the diffraction peak at 14.8°, a series of Bragg reflections at low angles (2θ < 14.8°) are observed for these quasi-2D perovskites (Fig.1b). This indicates that the PEA group with large size is incorporated, and the size of unit cells is enlarged compared with 3D perovskite14,25,36. According to the analysis shown in Supplementary Table 2 and the unit cells of n-phases shown in Fig.1a, it is found that the diffraction peaks (2θ < 14.8°) are attributed to the n = 1 and n = 2 phases (diffraction patterns from n ≥ 3 phases are not observed here). Specifically, for n = 1 composition, only the n = 1 phase exists; for n = 2 composition, the n = 1 and n = 2 phases are both presented in the films. It is unexpected that diffraction peaks of the n = 1 phase is absent in the n = 3 composition, while obvious diffraction peaks from the n = 2 phase are observed. For n ≥ 4 compositions (n > 4 compositions are not shown here due to very weak small n-phases diffractions), the diffraction peaks from small n-phases become weak or absent.

The photoluminescence (PL) results of the quasi-2D perovskite films with different compositions are shown in Fig. 1c, and the 2D (n = 1) and 3D (n = ∞) perovskite films are also included for comparison. The 2D perovskite shows an emission at 412 nm (3.01 eV) and the long tail21,37 at a longer wavelength, which could be due to the self-trapped exciton emission21 or the disordered structure. The 3D perovskite showed a band edge emission peak at 542 nm (2.29 eV)38. All quasi-2D perovskite films have two main emission peaks: one in the green region (approximately 532 nm, approximately 2.33 eV) and another in the blue region (at 440 nm, 2.82 eV). Comparing the PL with the absorption spectra (Fig.1c and Supplementary Fig. 4), it can be found that the stronger green emission at approximately 532 nm comes from large n-phases (n→∞) or 3D perovskite, and the weaker blue emission at 440 nm comes from the n = 2 phase. The emission phases we find are nearly almost consistent with the XRD results. There are some exceptions: for the n = 2 composition, we have not observed the n = 1 phase emission, while the n = 4 composition shows an emission at 405 nm from the 2D perovskite phase (n = 1), and the reason for this is not clear at present.

The relative PL intensity and emission peak wavelength in the green emission from the quasi-2D perovskites and 3D perovskite are plotted in Fig. 1d. It is found that the n = 3 composition film shows the brightest green emission. The significant blue-shift of the green emission from quasi-2D perovskites is observed compared with the 3D perovskite. In addition, a smaller n-composition showed a larger blue-shift, indicating that the blue-shift is due to the quantum confinement effect. The emission images of these quasi-2D perovskite films under ultraviolet excitation (Fig. 1e) also confirms that the n = 3 composition shows the best PL.

Compared with 3D perovskites, significant enhancement of the PL is observed for quasi-2D perovskites (Fig.1c). This is due to the quantum confinement effect via the formation of quantum well structures between large bandgap phases (smaller n-phases) and small bandgap phases (n→∞ phase or 3D perovskite)13,14. The different emissions from various compositions observed in Fig.1c could be explained by the competition between confinement phase (small n-phase) and emission phase (large n-phase, n→∞ phase). Here, we use n = 2, 3, 4 compositions as examples. According to XRD results shown in Fig.1b, the n = 2 confinement phase and 3D emission phase dominate in n = 2 and n = 4 composition, respectively, and both of these will cause weak green emission. While the amount of n = 2 phase and 3D phase are adequate in the n = 3 composition, this could be the reason of the highest PL of n = 3 composition. The PLQY of the n = 3 shows a value as high as 57.3% under low density excitation (excitation wavelength of 400 nm, power density of 3.5 mW cm-2). The quantum well of n = 3 composition is mainly formed by the n = 2 and n→∞ phases (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Passivation of quasi-2D perovskite

Keeping in mind that the n = 3 composition of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 perovskite could be a good candidate for an emitting material, we further improve its emission by surface passivation. An organic small molecule TOPO is spin-coated onto the perovskite surface to form a thin passivation layer31. It is found that the PLQY of the n = 3 composition film was significantly increased from 57.3% to 73.8% after coating with the TOPO layer (Fig. 2a), confirming the passivation effect of the TOPO layer. The average fluorescence lifetime of the n = 3 composition film is also increased from 0.17 μs to 0.36 μs after TOPO treatment (Fig. 2b). Although a small red-shift in PL spectra has been observed for the TOPO-treated 3D perovskite film previously31, no obvious modulation of PL due to TOPO treatment is observed in this study (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Fig. 2.

Passivation effect of TOPO on the perovskite with n = 3 composition. a Photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of the PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) perovskite films with and without TOPO passivation. b Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) of the PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) films with and without TOPO passivation layer. c Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy measurement for TOPO, PbBr2 and TOPO-PbBr2 films prepared on silicon wafers

The passivation of halide perovskites is ascribed to the chemical interaction between molecular ligands and incomplete PbI6-octahedra in previous study39. To confirm this, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy measurements were carried out, and the result is shown in Fig. 2c. An absorption peak located at 1150 cm−1 is observed for TOPO, which corresponds to P=O bond stretching vibrations40. This P=O bond absorption peak shifts to approximately 1100 cm−1 in the film comprised of TOPO and PbBr2, indicating that the bonding between perovskite and TOPO could be formed41,42.

Device structure and performance

We configure PeLEDs as the structure glass/ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4/TPBi/LiF/Al. Modified PEDOT:PSS (m-PEDOT:PSS) is used as the hole injection layer (HIL), TPBi/LiF as the electron injection layer (EIL) and the quasi-2D perovskites as the emitting layer. The band alignment for all function layers is shown in Fig. 3a, and TOPO shown in the figure acts as a thin passivation layer on the perovskite film. Br-based perovskites usually exhibit a deeper valence band (approximately −6.0 eV, Supplementary Fig.5) than that of PEDOT:PSS (approximately −5.2 eV). We doped PSS-Na into PEDOT:PSS to increase the work function43, which can improve hole injection as well as device performance (Supplementary Fig.13). The cross-section scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the completed device is shown in Fig. 3b, and a clear sandwich device structure is observed. The thicknesses of m-PEDOT:PSS (HIL), the perovskite layer and TPBi (EIL) are about 50, 110 and 30 nm, respectively. The typical EL spectra of the n = 3 composition-based PeLEDs under different voltage bias are shown in Fig. 3c. Although the perovskite films exhibit a mixture of many phases with different bandgaps, only single green EL is observed, even in logarithmic scale (Supplementary Fig. 8), which is different from the PL. It can be estimated that the charge density injected by EL (1017 s−1 cm−2) is two orders higher than that excited by PL (1015 s−1 cm−2) under injection/excitation of 5.1 V, 30 mA cm−2 and 1 mW cm−2, 340 nm excitation, respectively, while the blue emission is still not observed in EL. This could be due to the different working mechanism between EL and PL. For the PL, the photo-excited charges are driven from a larger bandgap phase to a smaller bandgap phase by their conduction/valence band energy difference. However, for EL, the driving force is not only the energy difference, but also the applied external electric field. As a result, most charges will be injected and recombined in the smallest band gap phases. This could be the reason that only green EL is observed even under high charge density injection. The EL peak is located at 532 nm, and the full width at half maximum is about 23 nm. The emission of our PeLEDs exhibited a good color purity (95%) in the green region, with Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE) chromaticity coordinate at (0.21, 0.75) (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Perovskite light-emitting diodes structure and electroluminescence. a Band alignment of each function layer in the devices. b Cross-section scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the device, the scale bar is 100 nm. c Typical electroluminescence (EL) spectra of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) based PeLEDs under different voltage bias. Inset shows the electroluminescence image of PeLEDs. d The corresponding Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE) coordinate of typical PeLEDs based on PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition)

We characterize the PeLEDs with different compositions (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 9). It is found that the n = 2 composition showed the lowest injection current (Supplementary Fig. 9), which could be due to the poor transport properties of 2D phase. Correspondingly, the brightness and CE of n = 2 composition-based devices are both the lowest (Fig. 4a, b). The compositions of n = 3 and n = 4 based PeLEDs show the maximum brightness of about 7000 cd m−2 and 8700 cd m−2, respectively, while n = 3 composition shows a higher CE (40.2 cd A−1) than n = 4 composition (37.6 cd A−1). For the n = 5 and n = 6 compositions, consistent with their PL efficiency (Fig.1c, e), their EL also could not compare with that of n = 3 composition. The detailed device performances for various compositions are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 4.

Device performance of perovskite LEDs with different compositions and surface passivation. a Luminance–voltage (L-V) curves of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 with different compositions. b Current efficiency–voltage (CE-V) curves of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 with different compositions. c Luminance–voltage (L-V) curves of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) devices with and without TOPO layer. d Current efficiency–voltage (CE-V) curves of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) devices with and without TOPO layer. e External quantum efficiency (EQE) of the champion device of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 (n = 3 composition) with TOPO passivation layer. f Histogram of maximum EQEs measured from 60 devices

Table 1.

Device performance based on quasi-two-dimensional perovskites PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4

| Compositions | Lmax (cd m−2) | Current efficiency (cd A−1) | Maximum EQE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2 | 717 | 5.98 | 1.54 |

| n = 3 | 6973 | 40.20 | 9.29 |

| n = 3 (best) | 7829 | 52.51 | 12.12 |

| n = 4 | 8779 | 37.61 | 8.45 |

| n = 5 | 3452 | 20.95 | 4.82 |

| n = 6 | 2281 | 16.77 | 4.00 |

| n = 3 and TOPO | 9120 | 62.43 | 14.36 |

We next discuss the role of surface passivation in performance improvement for n = 3 composition. It is found that the turn-on voltage increases and the injection current decreases after introducing a TOPO layer (Supplementary Fig.10). This is due to the insulating property of TOPO and indicates that the TOPO is successfully coated on the perovskite surface. Figure 4c shows the brightness curve of the PeLEDs with and without TOPO. The maximum brightnesses of the PeLEDs with and without passivation are at the same level, while the devices with passivation showed higher CE (Fig. 4d). The best performing device without TOPO passivation shows a CE of 52.5 cd A−1, while TOPO-treated devices show a CE as high as 62.4 cd A−1, and the power efficiency also increased from 49.4 lm W−1 to 53.3 lm W−1 (Supplementary Fig.11). Accordingly, a high EQE of 14.36% is obtained (Fig. 4e). We also find that our devices show good reproducibility. The EQE histogram for 60 devices from five batches are presented, showing an average EQE of 13.1% with a low relative standard deviation of 4.4% (Fig. 4f).

Discussion

Device stability is still a critical and common issue in PeLEDs. The stability of our PeLEDs with encapsulation was tested under a constant injection current in dry air (Supplementary Fig. 14). The luminance and CE increased at the beginning for several minutes, which could be due to trap filling15 that results in the improvement of electrical contacts. After that, the device performance gradually decreased, and finally the devices work for approximately 120 min. We also noticed that larger injection current induces faster degradation, which could be due to heat accumulation or ion movements. Our device showed the almost same level stability of I-related perovskite with the stability in several 100 min15. Compared with the Br-related perovskite with several 10 min stability in previous reports15,44, our devices showed a little bit improvement.

Further improvement of PeLED stability is necessary, and we assume that there are several issues leading to PeLED instability. One major issue could be ion migration under voltage bias, and another issue could be the phase stability of perovskite materials under heating or moist conditions. Several strategies could be adopted to improve PeLED stability such as finding stable perovskite-emitting materials19,45, incorporating suitable groups to avoid or suppress the ion movements12,19, seeking effective ligands17,46 to bond with the grain surface and also the film surface to reduce Joule heating induced by non-radiative recombination and finding stable charge injection layers47.

In summary, by composition/phase engineering, we find that a quasi-2D perovskite of PEA2(FAPbBr3)n-1PbBr4 with n = 3 composition showed good PL. We also introduce surface passivation to reduce the non-radiative recombination on the perovskite surface or grain boundaries. Combining composition/phase engineering and surface passivation, high performance of quasi-2D PeLEDs with a CE of 62.4 cd A-1 and an external quantum efficiency of 14.36% is achieved.

Methods

Materials

The modified PEDOT:PSS (m-PEDOT:PSS) solution is a mix of normal PEDOT:PSS (AI 4083) aqueous solution and 100 mg ml−1 PSS-Na (Sigma Aldrich) aqueous solution by a volume ratio of 6:5. TOPO, PbBr2, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and chlorobenzene (CB) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. 2,2’,2”-(1,3,5-Benzinetriyl)- tris(1-phenyl-1-H-benzimidazole) (TPBi) and formamidinium bromide (FABr) and methylammonium chloride (MACl) were purchased from Xi’an Polymer Light Technology Corp. Phenylethylammonium bromide (PEABr) was purchased from Dyesol (now Greatcell Solar).

Device fabrication

The indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass substrates were sequentially cleaned in detergent, distilled water, acetone and isopropanol by sonication and used as anode. The cleaned substrates were ultraviolet ozone treated for 15 min to make the surface hydrophilic, then m-PEDOT:PSS (or normal PEDOT:PSS) aqueous solution was spin-coated at 9000 rpm (or 2500 rpm) for 40 s and baked at 160 °C for 15 min in ambient air. Thereafter, the substrates were transferred into a nitrogen-filled glove box, and the 0.6 mol l−1 (Pb2+concentration) perovskite solution in DMSO was spin-coated onto the m-PEDOT:PSS (or normal PEDOT:PSS) films at 3000 rpm for 2 min, and after spin coating for 40 s, 100 µl of CB was poured onto the film for pinning the perovskite crystallization, followed by annealing on a hot plate at 90 °C for 1 h. The perovskite precursor solution was prepared according to Supplementary Table 1. For surface passivation, 2 mg ml−1 TOPO in CB was dripped onto the perovskite film for a 1 min to let TOPO passivate the film surface enough and then spin-coated at 7000 rpm for 1 min. Finally, the fabrication of PeLEDs was completed by depositing TPBi, LiF (less than 1 nm) and Al electrode layer by layer through a shadow mask in a high vacuum thermal evaporator. The device area was 0.108 cm2 as defined by the overlapping area of the ITO and Al electrode. The thickness of ITO and Al are 130 nm and 60 nm, respectively.

Material and device characterizations

XRD measurements were performed with a Rigaku D/max 2500H equipment with a conventional Cu target X-ray tube (Cu K-alpha, λ = 1.5418 Å) set to 40 kV and 200 mA. Steady-state PL spectra and time-resolved fluorescence spectra (TRPL) of the perovskite films were measured at room temperature in the ambient air using a fluorescent spectrophotometer (HORIBA JY Nanolog-TCSPC). The excitation wavelength for PL and TRPL are both 340 nm, which were provided by 450 W xenon lamp and a pulsed diode laser (NanoLed-340), respectively. The PLQY of the perovskite films was measured using an Edinburgh FLS920 equipment with a 450 W xenon lamp as excitation source. The following settings were applied for PLQY measurements: excitation wavelength of 400 nm; bandpass values of 3.00 and 0.35 nm for the excitation and emission slits, respectively; step increments of 0.5 nm and integration time of 0.3 s per data point. We measured the light intensity with a laser power meter and the estimated light power density incident on the samples was about 3.5 mW cm−2. The ultraviolet–visible absorbance spectra were recorded on an ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Cary 5000, Varian). The FTIR spectra were recorded on an infrared spectrophotometer (Excalibur 3100, Varian) in a general mode that did not use attenuated total reflection component. AFM images of the perovskite films were collected in non-contact mode (Bruker FASTSCANBIO). The cross-sectional image of PeLEDs was made on a scanning electron/focused ion beam double-beam equipment (FEI Nova200 NanoLab) operated at 2 kV. Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) spectra were collected on a Thermo Scientific ESCALab250Xi equipment with an applied bias of −10 V. He I ultraviolet radiation source (21.22 eV) was used. The helium pressure in the analysis chamber during measurement was about 2E−8 mbar. The film samples over the ITO layer had a conductive connection with an Au sample, so the Fermi level value of the film samples is equal to that of Au sample. The work function ϕ (that is the Fermi level absolute value of the free film) of the test films can be calculated from following equation: hν − ϕ = EFermi – Ecutoff, where EFermi and Ecutoff are respectively the value of Fermi level position and the steep edge position in the UPS spectrum of the test film, hν = 21.22 eV, EFermi is 21.02 eV for Au. Two Keithley 2400 source meter units linked to a calibrated silicon photodiode were used to measure the current–voltage–brightness characteristics. The measurement system was carefully calibrated by a Hamamatsu C9920-02G equipment and a 100 mm integrating sphere of Enli Technology using our perovskite LEDs. Lambertian profile was used in the calculation of EQE. All the device characterization tests of perovskite LEDs were carried out at room temperature in the ambient air for the un-encapsulated devices, except that operational stability test was carried in dry air for the encapsulated devices.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 61574133, 61634001), National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2016YFB0700700), National 1000 Young Talents awards and Young top-notch talent project of Beijing.

Author contributions

J.Y. conceived the idea, designed the experiment and analyzed the data. X.Y. fabricated devices and collected all data. X.Z., J.D., Z.C., Q.J., J.M., P.W., L.Z. and Z.Y. were involved in data analysis. J.Y. and X.Y. co-wrote the manuscript. J.Y. directed and supervised the project. All authors contributed to discussions and finalization of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03702-1.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-02978-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Deschler F, et al. High photoluminescence efficiency and optically pumped lasing in solution-processed mixed halide perovskite semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1421–1426. doi: 10.1021/jz5005285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xing G, et al. Low-temperature solution-processed wavelength-tunable perovskites for lasing. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:476–480. doi: 10.1038/nmat3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Protesescu L, et al. Nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X=Cl, Br, and I): novel optoelectronic materials showing bright emission with wide color gamut. Nano Lett. 2015;15:3692–3696. doi: 10.1021/nl5048779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F, et al. Brightly luminescent and color-tunable colloidal CH3NH3PbX3 (X=Br, I, Cl) quantum dots: potential alternatives for display technology. ACS Nano. 2015;9:4533–4542. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song J, et al. Quantum dot light-emitting diodes based on inorganic perovskite cesium lead halides (CsPbX3) Adv. Mater. 2015;27:7162–7167. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Protesescu L, et al. Monodisperse formamidinium lead bromide nanocrystals with bright and stable green photoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14202–14205. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levchuk I, et al. Brightly luminescent and color-tunable formamidinium lead halide perovskite FAPbX3 (X=Cl, Br, I) colloidal nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2017;17:2765–2770. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovalenko MV, et al. Properties and potential optoelectronic applications of lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Science. 2017;358:745–750. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan ZK, et al. Bright light-emitting diodes based on organometal halide perovskite. Nat. Nanotech. 2014;9:687–692. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, et al. Interfacial control toward efficient and low-voltage perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:2311–2316. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho H, et al. Overcoming the electroluminescence efficiency limitations of perovskite light-emitting diodes. Science. 2015;350:1222–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, et al. Ultra-bright and highly efficient inorganic based perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15640. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan MJ, et al. Perovskite energy funnels for efficient light-emitting diodes. Nat. Nanotech. 2016;11:872–877. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang N, et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on solution-processed self-organized multiple quantum wells. Nat. Photon. 2016;10:699–704. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao ZG, et al. Efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes featuring nanometre-sized crystallites. Nat. Photon. 2017;11:108–115. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland BR, Sargent EH. Perovskite photonic sources. Nat. Photon. 2016;10:295–302. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.62. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veldhuis SA, et al. Perovskite materials for light-emitting diodes and lasers. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:6804–6834. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YH, Cho H, Lee TW. Metal halide perovskite light emitters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:11694–11702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607471113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling Y, et al. Enhanced optical and electrical properties of polymer-assisted all-inorganic perovskites for light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:8983–8989. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Era M, et al. Electroluminescent device using two dimensional semiconductor (C6H5C2H4NH3)2PbI4 as an emitter. Synth. Met. 1995;71:2013–2014. doi: 10.1016/0379-6779(94)03142-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dou L, et al. Atomically thin two-dimensional organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites. Science. 2015;349:1518–1521. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith IC, et al. A layered hybrid perovskite solar-cell absorber with enhance moisture stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11232–11235. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai H, et al. High-efficiency two-dimensional Ruddlesden-Popper perovskite solar cells. Nature. 2016;536:312–316. doi: 10.1038/nature18306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan LN, et al. Ligand-stabilized reduced-dimensionality perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2649–2655. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byun J, et al. Efficient visible quasi-2D perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:7515–7520. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reineke S, et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature. 2009;459:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature08003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pimputkar S, et al. Prospects for LED lighting. Nat. Photon. 2009;3:180–182. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noel NK, et al. Enhanced photoluminescence and solar cell performance via Lewis base passivation of organic-inorganic lead halide perovskites. ACS Nano. 2014;8:9815–9821. doi: 10.1021/nn5036476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, et al. Phenylalkylamine passivation of organolead halide perovskites enabling high-efficiency and air-stable photovoltaic cells. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:9986–9992. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.deQuilettes DW, et al. Impact of microstructure on local carrier lifetime in perovskite solar cells. Science. 2015;348:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.deQuilettes DW, et al. Photoluminescence lifetimes exceeding 8 μs and quantum yields exceeding 30% in hybrid perovskite thin films by ligand passivation. ACS Energy Lett. 2016;1:438–444. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon NJ, et al. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic–organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nmat4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.You J, et al. Low-temperature solution-processed perovskite solar cells with high efficiency and flexibility. ACS Nano. 2014;8:1674–1680. doi: 10.1021/nn406020d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stranks SD, et al. Electron-hole diffusion lengths exceeding 1 micrometer in an organometal trihalide perovskite absorber. Science. 2013;342:341–344. doi: 10.1126/science.1243982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meng L, et al. Pure formamidinium-based perovskite light-emitting diodes with high efficiency and low driving voltage. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1603826. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quan LN, et al. Tailoring the energy landscape in quasi-2D halide perovskites enables efficient green-light emission. Nano. Lett. 2017;17:3701–3709. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang D, et al. Color-pure violet-light-emitting diodes based on layered lead halide perovskite nanoplates. ACS Nano. 2016;10:6897–6904. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b02683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arora N, et al. Photovoltaic and amplified spontaneous emission studies of high-quality formamidinium lead bromide perovskite films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:2846–2854. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201504977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bi DQ, et al. Polymer-templated nucleation and crystal growth of perovskite films for solar cells with efficiency greater than 21% Nat. Energy. 2016;1:16142. doi: 10.1038/nenergy.2016.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayou N, et al. Elaboration and characterisation of a plasticized cellulose triacetate membrane containing trioctylphosphine oxyde (TOPO): application to the transport of uranium and molybdenum ions. C. R. Chim. 2010;13:1370–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2010.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Söderlind F, et al. Synthesis and characterisation of Gd2O3 nanocrystals functionalised by organic acids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;288:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.02.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang SM, Lo PH, Chang CT. Photocatalytic behavior of TOPO-capped TiO2 nanocrystals for degradation of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009;91:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuo CT, Ding LM. Modified PEDOT layer makes a 1.52 V VOC for perovskite/PCBM solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016;7:1601193. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201601193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, et al. Enhancing the brightness of cesium lead halide perovskite nanocrystal based green light-emitting devices through the interface engineering with perfluorinated ionomers. Nano. Lett. 2016;16:1415–1420. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulbak M, Cahen D, Hodes G. How important is the organic part of lead halide perovskite photovoltaic cells? Efficient CsPbBr3 cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2452–2456. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, et al. 50-Fold EQE improvement up to 6.27% of solution-processed all-inorganic perovskite CsPbBr3 QLEDs via surface ligand density control. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1603885. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.You J, et al. Improved air stability of perovskite solar cells via solution-processed metal oxide transport layers. Nat. Nanotech. 2016;11:75–81. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.