Abstract

Background:

Coercive measures are applied in psychiatry as a last resort to control self- and hetero-aggressive behaviors in situations where all other possible strategies have failed. For ethical and clinical reasons, the number of instances of coercion should be reduced as far as possible.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to identify sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients that were associated with coercion during hospital treatment.

Materials and Methods:

The study has a descriptive, longitudinal design, based on a 1 year prospective observation of patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital consisting of six inpatient psychiatric wards with a total of 236 beds.

Results:

In the 12-month period covered by the study, 1476 people (778 men and 698 women) were treated in the hospital; 226 of them (15%) were subjected to coercion on a total of 405 occasions. The most frequently implemented form of direct coercion was mechanical restraint. The following factors involved in the use of direct coercion were identified: Male gender, young age, mental disorders resulting from the abuse of psychoactive drugs, involuntary admission to the hospital and the use of direct coercion in the past.

Conclusion:

Assessments of patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics can help clinicians recognize patients who are particularly at risk of being subjected to coercive measures.

Keywords: Coercion, involuntary treatment, physical restraint

INTRODUCTION

In the treatment of the mentally disturbed, it is admissible to use coercion, which in broader terms includes depriving a patient of personal freedom and involuntary commitment.[1]

Apart from involuntary commitment (indirect coercion), psychiatric treatment can involve direct physical pressure on a patient, defined as direct coercion. The admissibility of direct coercion, the extent of its use and its compliance with current laws constitute a significant problem in psychiatric institutions and frequently affect, rightly or not, how society at large views psychiatry, while involuntary admissions have a legal framework in all European countries, detailed regulations concerning coercive measures (mechanical restraint, seclusion, and forced medication) exist only in some countries.[2]

In accordance with the standards of international law, direct coercion is treated as a last resort in the treatment of the mentally disturbed. When choosing how to apply it, the principle of the least distress for the patient is recommended.[3] The literature frequently emphasizes the adverse effects – on both the patients and the personnel – of the use of direct coercion. It can be dangerous for a patient in bad physical condition. Infectious diseases, cardiologic, metabolic or thermoregulatory disorders, and other ailments requiring constant medical supervision are contraindications to solitary confinement.[4] Reports indicate that patients subjected to mechanical restraint are at an increased risk of choking and peripheral thrombosis, and are also more likely to become targets of other patients’ aggression.[5] Isolated instances have been reported of deaths of patients who were submitted to mechanical restraint in an acute delirium state.[6] The reduction of sensory stimuli caused by restraint or isolation adversely affects the mental condition of patients with organic damage to the central nervous system.[5]

The frequency with which coercive measures are used may be influenced by patient- or ward-related variables. This work aims to analyze the effect of factors related to the patient – such as age, gender, psychiatric diagnosis, the number of previous hospitalizations, previous instances of being subjected to direct coercion and the legal basis of the hospital admission – on the frequency of use of direct coercion in the cases of mentally disordered patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study has a descriptive, longitudinal design, based on a 1 year prospective observation of patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital that serves a population of 650,000 inhabitants. The hospital consists of six inpatient psychiatric wards with a total of 236 beds. The material studied in this work comprised all instances of the use of direct coercion in 12 months, reported in accordance with article 18 of Poland's Mental Health Act.

Direct coercion was defined in accordance with article 18 of Poland's Mental Health Act:

-

“In the course of activities covered by this Act, mentally disturbed persons may be submitted to physical coercion only when such persons:

-

Make an attempt:

- Against their own life or health, or the life or health of another person,

- Or against public safety,

- or when such persons violently destroy or damage surrounding objects,

- or when such persons seriously disturb or preclude the functioning of the healthcare entity which provides health services in the field of mental health care or social welfare center, physical restraint is warranted by special regulations of this Act

-

Physical coercion used on persons referred to in paragraph 1.1 and 1.2 consists in physical restraint, forced medication, mechanical restraints or seclusion. Physical coercion used on persons referred to in paragraph 1.3 consists in physical restraint and forced medication.”

Data analysis

The clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the sample were analyzed by descriptive statistics. The statistical significance of differences between two mean values in results with the properties of interval variables was assessed with the parametric t-test for independent samples if the data distribution was normal or with the parametric Cochran Cox test for unequal variances. To compare more than two means, parametric analysis of variances (ANOVA) algorithms were used, depending on the results of tests assessing the normality of distribution and the homogeneity of variances. A confidence level of P = 0.05 was adopted for all the tests assessing the statistical significance of the differences between means. If the ANOVA showed statistically significant differences between means, a post hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference test for unequal sample sizes was carried out.

RESULTS

In the 12-month period covered by the study, 1476 people were treated in the hospital (778 men and 698 women). The average age of the patients was 44 years. Among them, 226 (15%) were submitted to coercion on a total of 405 occasions. The complete data necessary for the analysis were obtained for 183 patients, who experienced a total of 274 instances of direct coercion. Men predominated in the sample: 117 (64%) as opposed to 66 women (36%). The women were subjected to direct coercion 106 times, and the mean number of instances of direct coercion for a patient in this group was 1.6 (range: 1–5). In the group of men 168 instances were noted, making the mean in this group 1.4 incidents per patient (rang: 1–5).

In the general population of patients hospitalized during the research period, the proportion of men and women was 53% and 47% respectively, while in the group of patients subjected to direct coercion the proportion of men increased to 64% and the proportion of women decreased to 36%. To determine how a patient's gender influences the use of direct coercion, the proportion of men and women subjected to it was compared with the percentage of men and women in the general population of hospitalized patients. A two-sided test of proportions was carried out and revealed that this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.000). These results show that the structure of the group of patients subjected to direct coercion, analyzed in terms of gender, differs from the general population of hospitalized patients, i.e., the proportion of men was higher in the former group.

The age of the patients in the study group ranged from 18 to 78 years, with a mean of approximately 41 years. The mean age of women (43 years) was higher than that of men (40 years). The mean age of all the patients hospitalized in the period in question was higher than that of the patients subjected to direct coercion: 44 years (P < 0.000) (41 and 48 years for men and women, respectively).

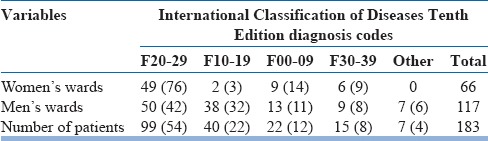

The diagnosed mental disorders of the subjects of the study according to the ICD-10 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The numbers and percentages of patients subjected to direct coercion in relation to their psychiatric diagnoses

Patients with diagnoses of F20–29 constituted the greatest proportion of people subjected to direct coercion – approximately 54%, while in the general population of hospitalized patients the percentage with diagnoses of F20–29 was 49%. A one sample test of proportions (two-sided) did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the proportion of patients subjected to direct coercion diagnosed with F20–29 and the general population of hospitalized patients with F20–29 diagnoses.

The patients diagnosed with mental disorders caused by the abuse of psychoactive drugs (F10–19) constitute the second largest group, both in the overall hospitalized population and among those subjected to direct coercion. The proportion of patients with diagnoses of F10–19 in the general patient population was about 15%, while in the population of patients subjected to direct coercion it was approximately 21%. A one sample test of proportions (two-sided) confirmed that the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Z = 2.30).

The next most numerous group of psychiatric diagnoses among the patients subjected to direct coercion comprised organic mental disorders (F00–09). In the general hospital, population organic mental disorders were diagnosed in 10% of the patients, while the proportion was 12% among the subjects of the study. A one sample test of proportions (two-sided) showed that this difference was not statistically significant.

The proportion of patients diagnosed with mood disorders (F30–39) among the study subjects was 8%, while it was 13% in the whole hospitalized population. A one sample test of proportions (two-sided) proved that this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05, Z = 2.08).

Other mental disorders diagnosed in the whole population of the hospitalized were rarely noted in the group of patients subjected to direct coercion.

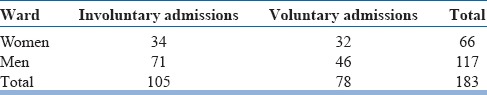

The characteristics of the population of patients subjected to direct coercion in terms of the legal grounds for their admission to the hospital are presented in Table 2. The study group included 105 patients who had been admitted involuntarily, comprising 34 women and 71 men. Among the female subjects of the study, involuntarily admitted patients constituted approximately 50%, while among the men the proportion was approximately 60%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients subjected to direct coercion: The legal grounds for admission

Among the patients who were subjected to direct coercion, 57% had been admitted involuntarily, while in the general hospital population the proportion of patients admitted involuntarily was 24%. To determine how the legal grounds for admission influences the use of direct coercion, the proportions of voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients subjected to direct coercion were compared with the percentages voluntarily and involuntarily patients in the whole population of the hospitalized patients. A two-sided test of proportions revealed that the difference is statistically significant (P < 0.000).

In the study group, 65 patients (36%) were subjected to direct coercion in the emergency room while being admitted to the hospital, including 48 men (41%) and 17 women (26%).

Legally admissible forms of direct coercion were used in the hospital wards – restraints, forced medication, and physical restraint; seclusion was not employed. Mechanical restraints were the most frequently used form (mean per patient: 1.23). The next most frequently used measure was forced medication (mean per patient: 1.06), while the mean of use of physical restraint was 0.211 per patient.

A one-way ANOVA in which direct coercion used in the past was the independent variable and the number of instances of direct coercion was the dependent variable showed that there were statistically significant differences in terms of the number of instances of direct coercion (df group 1, F = 4.105, P < 0.046) between the group of patients previously subjected to direct coercion and those who had not previously experienced it.

A detailed analysis of means carried out using Tukey's test revealed a statistically significant difference between the means of the variable the number of instances of direct coercion in the two sets of patients being analyzed: A higher mean number of instances of direct coercion per patient was noted in the group of patients previously subjected to direct coercion (1.853 vs. 1.4082).

DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

The group of patients subjected to direct coercion was distinctly predominated by men; the proportion of men in this group was higher than in the general population of hospitalized patients. The influence of gender on coercion has been explored in numerous studies, most of which failed to identify any impact of gender on the use of coercion.[7,8,9,10,11] Only a few have reported an association with male gender.[12,13,14] This may be explained by the fact that most of these studies discussed the effect of gender in relation to a given coercion measure, such as isolation, physical restraint, mechanical restraints or forced medication, while the present study tested gender in relation to coercion in general.

The mean age of patients subjected to direct coercion was 41 years, which was lower than that of the general population of hospitalized patients (approximately 44 years). The men subjected to direct coercion were younger than the women; the mean ages were 40 and 43 years, respectively. These results reveal that there is a tendency for the mean age in the group of patients subjected to direct coercion to be lower than the mean age of the general population of patients. A substantial number of studies have found a relationship between younger patients and the frequency of use of direct coercion.[9,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]

The patients subjected to direct coercion were involuntarily admitted to the hospital distinctly more frequently than the general population of hospitalized patients. As many as 60% of the men subjected to direct coercion were admitted involuntarily, while in the corresponding group of women the proportion was about 50%. A correlation between the frequency of direct coercion and involuntary admission has been confirmed by other authors.[9,22,23,24,25] According to an EUNOMIA (European Evaluation of Coercion in Psychiatry and Harmonization of Best Clinical Practice) study, almost 40% of involuntarily admitted patients in Europe experienced some form of coercion during their treatment. In contrast to Spain, where the lowest level of use of coercive measures was found (21%), patients in Poland are at the highest risk of being subjected to coercive measures when admitted to a psychiatric ward (59% of all patients).[26]

The patients most frequently subjected to direct coercion were those diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F20–29) – both men and women. Patients diagnosed with F20–29 also predominated in the hospital's general population. This study did not find statistically significant differences between the study subjects and the general population of hospitalized patients in terms of the frequency of occurrence of F20–29 diagnoses. Authors of previous studies have reported that a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder was a risk factor consistently associated with the likelihood of being subjected to coercive measures.[23,25,27,28,29]

The second most numerous group of patients subjected to direct coercion consisted of those diagnosed with mental disorders caused by the abuse of psychoactive drugs (F10–19). Patients with F10–19 diagnoses constituted 15% of the general hospital population, but approximately 21% of the patients subjected to direct coercion– a statistically significant difference. A diagnosis of a disorder caused by substance abuse is recognized as a risk factor for the use of coercive measures.[9,28]

The proportion of patients diagnosed with mood disorders (F30–39) was lower in the group of those subjected to direct coercion than in the general hospital population, and the difference was statistically significant. The smaller proportion of patients subjected to direct coercion recorded in this diagnostic group is probably related to the lower percentage of women in the study group than in the general hospital population (9% and 16%, respectively).

Further analysis revealed a relationship between the use of direct coercion in the past and the number of instances of its use per patient: People who had experienced such measures in the past were subjected to direct coercion more frequently (1.853 instances per person) than those who had not previously experienced it (1.4082 instances per person). Published research results confirm that aggressive behavior in the past is a predictive factor for the reoccurrence of instances of similar behavior.[30,31,32,33,34,35] The results of the present study indicate that direct coercion noted in a patient's medical history may also be a significant factor enabling medical personnel to predict the occurrence of dangerous behavior, which is the most frequent cause of the use of direct coercion. Due to the requirements of the Mental Health Act, information concerning the use of direct coercion should be more easily available in patients’ records than data concerning aggressive behavior, which would enable the personnel to give those patients particular attention and adjust their medical care to their particular needs. On the other hand, information confirming the previous use of direct coercion may stigmatize a patient, and the medical personnel may become prejudiced against that patient's behavior, which in effect may facilitate a decision to use direct coercion in ambiguous situations.

In the present study, mechanical restraints were the most frequently used form of coercion; Knutzen et al.[36] found the same. The distribution of restraint categories for the 371 patients subjected to it was as follows: mechanical restraint – 47.2%; mechanical and pharmacological restraint combined – 35.3%; and pharmacological restraint – 17.5%.

The fact that 65 subjects (36%) were subjected to direct coercion during the process of being admitted to the hospital means that for a substantial number of patients the reasons for the use of coercion measures were not factors directly connected with the hospital conditions. According to Andersen and Nielsen,[37] being referred to the hospital, transported and examined can induce alarming behavior on the part of a mentally disturbed person, leading to the admissions personnel to use direct coercion. A patient's behavior may also be affected by other environmental factors.

The factors that our study found to be related to the use of coercion, such as male gender, young age, mental disorders caused by psychoactive drug abuse, involuntary admission to hospital and instances of direct coercion recorded in the medical history, are similar to those reported by Dack et al.[38] in their meta-analysis of patient characteristics associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression.

CONCLUSIONS

Assessing patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics can help clinicians recognize patients who are at risk for coercive measures. These factors should be taken into consideration by programs aimed at reducing the use of coercive measures in psychiatric wards.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by funding from Wroclaw Medical University.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kallert TW. Coercion in psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:485–9. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328305e49f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kallert TW, Torres-Gonzales F, editors. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang Publishing Inc; 2006. Legislation on Coercive Mental Health Care in Europe: Legal Documents and Comparative Assessment of Twelve European Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinert T, Lepping P, Baranyai R, Hoffmann M, Leherr H. Compulsory admission and treatment in schizophrenia: A study of ethical attitudes in four European countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutheil TG, Tardiff K. Indications and contraindications for seclusion and restraint. In: Tardiff K, editor. Washington, DC: America Psychiatric Press; 1984. pp. 11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hem E, Opjordsmoen S, Sandset PM. Venous thromboembolism in connection with physical restraint. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1998;118:2156–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollanen MS, Chiasson DA, Cairns JT, Young JG. Unexpected death related to restraint for excited delirium: A retrospective study of deaths in police custody and in the community. CMAJ. 1998;158:1603–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forquer SL, Earle KA, Way BB, Banks SM. Predictors of the use of restraint and seclusion in public psychiatric hospitals. Adm Policy Ment Health. 1996;23:527–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaltiala-Heino R, Korkeila J, Tuohimäki C, Tuori T, Lehtinen V. Coercion and restrictions in psychiatric inpatient treatment. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:213–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keski-Valkama A, Sailas E, Eronen M, Koivisto AM, Lönnqvist J, Kaltiala-Heino R, et al. Who are the restrained and secluded patients: A 15-year Nationwide Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:1087–93. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO, Lin HM, Altenor A, Altenor RJ, et al. Pennsylvania State hospital system's seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1115–22. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wynn R. Coercion in psychiatric care: Clinical, legal, and ethical controversies. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2006;10:247–51. doi: 10.1080/13651500600650026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter MD, Hannon VR, McCleery G, Wanderling JA. Variations in seclusion and restraint practices by hospital location. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:418–23. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luciano M, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Pingani L, Palumbo C, De Rosa C, et al. Use of coercive measures in mental health practice and its impact on outcome: A critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14:131–41. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2014.874286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lay B, Nordt C, Rössler W. Variation in use of coercive measures in psychiatric hospitals. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutinho ES, Allen MH, Adams CE. Physical restraints for agitated patients in psychiatric emergency hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A predictive model. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgieva I, Vesselinov R, Mulder CL. Early detection of risk factors for seclusion and restraint: A prospective study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2012;6:415–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason T. Gender differences in the use of seclusion. Med Sci Law. 1998;38:2–9. doi: 10.1177/002580249803800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller D, Walker MC, Friedman D. Use of a holding technique to control the violent behavior of seriously disturbed adolescents. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:520–4. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tardiff K. Emergency control measures for psychiatric inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1981;169:614–8. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray NK, Rappaport ME. Use of restraint and seclusion in psychiatric settings in New York State. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1032–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.10.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swett C. Inpatient seclusion: Description and causes. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1994;22:421–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Way BB, Banks SM. Use of seclusion and restraint in public psychiatric hospitals: Patient characteristics and facility effects. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:75–81. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husum TL, Bjørngaard JH, Finset A, Ruud T. A cross-sectional prospective study of seclusion, restraint and involuntary medication in acute psychiatric wards: Patient, staff and ward characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Merwe M, Bowers L, Jones J, Muir-Cochrane E, Tziggili M. Seclusion: A Literature Review. London: City University London, Disability DoMHaL; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tunde-Ayinmode M, Little J. Use of seclusion in a psychiatric acute inpatient unit. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12:347–51. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1665.2004.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalisova L, Raboch J, Nawka A, Sampogna G, Cihal L, Kallert TW, et al. Do patient and ward-related characteristics influence the use of coercive measures. Results from the EUNOMIA international study? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1619–29. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0872-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Betemps EJ, Somoza E, Buncher CR. Hospital characteristics, diagnoses, and staff reasons associated with use of seclusion and restraint. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:367–71. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Husum TL, Bjørngaard JH, Finset A, Ruud T. Staff attitudes and thoughts about the use of coercion in acute psychiatric wards. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:893–901. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinert T, Martin V, Baur M, Bohnet U, Goebel R, Hermelink G, et al. Diagnosis-related frequency of compulsory measures in 10 German psychiatric hospitals and correlates with hospital characteristics. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:140–5. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNiel DE, Binder RL, Greenfield TK. Predictors of violence in civilly committed acute psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:965–70. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.8.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNiel DE, Binder RL. Correlates of accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric inpatients’ risk of violence. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:901–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Apperson LJ, Evanczuk K, Shea S. Sources of disagreement among clinicians’ assessments of dangerousness in a psychiatric emergency room. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1992;15:237–50. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(92)90001-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steadman HJ. Predicting dangerousness among the mentally ill: Art, magic and science. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1983;6:381–90. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(83)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beauford JE, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Utility of the initial therapeutic alliance in evaluating psychiatric patients’ risk of violence. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1272–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apperson LJ, Mulvey EP, Lidz CW. Short-term clinical prediction of assaultive behavior: Artifacts of research methods. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1374–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.9.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knutzen M, Bjørkly S, Eidhammer G, Lorentzen S, Helen Mjøsund N, Opjordsmoen S, et al. Mechanical and pharmacological restraints in acute psychiatric wards – Why and how are they used? Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen K, Nielsen B. Coercion in psychiatry: The importance of extramural factors. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70:606–10. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2016.1190401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dack C, Ross J, Papadopoulos C, Stewart D, Bowers L. A review and meta-analysis of the patient factors associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:255–68. doi: 10.1111/acps.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]