Abstract

Context:

The concept of posttraumatic growth (PTG) is important to focus on positive outcomes of a challenging process like caregiving.

Aims:

The aim of the present study is to investigate the factors inclusively considered to be related to PTG in primary caregivers of schizophrenic patients.

Settings and Design:

This cross-sectional study was conducted with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia between January 2013 and February 2014 at a mental health hospital.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out on 109 schizophrenic patients followed up at Bakirkoy Prof. Dr. Mazhar Osman Research and Training Hospital for Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, and 109 family members who are the primary caregivers of the patients. All caregivers were evaluated with Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, Ways of Coping Inventory, and the Basic Personality Traits Inventory and Religious Orientation Scale.

Statistical Analysis:

Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U-test were used in quantitative analysis of data. Spearman's correlation analysis was used in the determination of correlation between variables. Linear regression analysis was used in the determination of predictors of PTG.

Results:

Optimistic and problem-focused coping, perceived social support (total and all three - family, friends, significant others - domains), personality traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience, and religiousness were found to be related with PTG. Religiousness, perceived social support, and openness to experience were independent predictors of PTG.

Conclusions:

Interventions to caregivers of schizophrenic patients on the domains of social support and coping strategies may contribute to caring process in a positive change.

Keywords: Caregivers, growth, schizophrenia, trauma

INTRODUCTION

All chronic diseases lead to functional deficits that result in caring process and therefore caregiver burden.[1] Schizophrenia is a chronic psychiatric disorder that causes functional deficits in almost all patients and brings with caregiver burden to family members particularly.[2] Burden and related factors in caregivers of schizophrenic patients have been investigated in different countries and cultures;[3,4] strategies and interventions to reduce family burden have been suggested.[5]

Schizophrenia, due to its course, is a disease considered as extremely traumatic for the family.[6] In the recent years, studies reporting caregiving experiences may provide a positive gain including personal development bringing a different point of view for impartibility of this traumatic event and burden concept.[7,8] Expressions of the fathers of the schizophrenic patients like “my marriage is stronger now, communication in our family became stronger, I met with excellent people during this period, and my daughter gave me a chance to look myself and understand how much I had become insensitive” can be given as examples of this different point of view.[8]

From this point of view, Calhoun and Tedeschi[9] defined posttraumatic growth (PTG) as “positive psychological change experienced as a result of challenges with hard life conditions and traumatic events.” Positive psychological change is investigated in five domains under PTG model: new possibilities, stronger relationships with other people, spiritual change/growth, personal strength, and a deeper appreciation of life.[10]

PTG has been started to take place in the literature since the past 25 years, and it has been studied in different areas including storm, massacre and airplane crash,[11] cancer,[12,13] infertility,[14] myocardial infarction,[15] siblings of people with mental disorders,[16] and families of schizophrenic patients.[17,18]

Based on previous research, it was hypothesized that PTG is related to coping styles such as problem-focusing,[18,19,20,21,22] social support,[18,21,23] religiousness,[24,25,26] and personality traits such as agreeableness, openness to experience, extraversion, and conscientiousness.[15,20]

The number of studies examining PTG and its related factors in families[17] and caregivers[18] of schizophrenic patients are very limited, and only a part of factors related to PTG are investigated in these researches. In this study, it is aimed to investigate the factors hypothesized to be related to PTG broader in family members of schizophrenic patients who are the primary caregivers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Patients with schizophrenia treated at the inpatient and outpatient psychiatry clinics of Bakirkoy Prof. Dr. Mazhar Osman Research and Training Hospital for Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, and their primary caregivers were included in the study, and data were obtained from 109 patients and 109 primary caregivers between January 2013 and February 2014.

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study, and individuals accepted to participate in the study were evaluated consecutively. The primary caregiver was defined as the member of the family who was most involved with the care of the outpatient. Primary caregiver had to live with the patient and had an effective role in follow-up of the treatment (e.g., accompanying the patient in outpatient clinic visits, take care of the patient when he/she is hospitalized, and follow up the medication compliance) and the areas with functional deficits (e.g., accompanying the patient when she/he is outside for shopping or a trip and take care of the patient for daily self-care activities if she/he needs). These properties of the family member were determined after the interviews with family members and he/she was defined as the primary caregiver. First, second, and forth authors evaluated patients and their caregivers. Approval for the study was granted by the Ethical Committee of the hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from both patients and their caregivers.

For a family member, being the primary caregiver of the patient, living with patient for at least 1 year, not having a physical (such as total auditory or visual lose), educational (not being literate), or mental disorder (such as mental retardation, psychosis, or dementia), which is an obstacle for filling the scales or the interview, were the inclusion criteria. Caregivers who were under 18 years old or who did not accept to participate in the study were not enrolled.

Patients who were diagnosed as having schizophrenia for at least 1 year after the end of interview with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, did not have alcohol or substance addiction or abuse for at least 1 year, did not have a physical disease or mental retardation obstacle for interview, did not have additional physical disease which could cause functional deficits (such as hemiplegia, multiple sclerosis, and epilepsy), and who accepted to participate in the study were enrolled in the study.

Tools for patients

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

It is a semi-structured clinical interview form which was developed by First et al.[27] according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition diagnostic criteria for Axis I disorders. It was adjusted to Turkish by Corapcioglu et al.,[28] and validity and reliability studies were performed for our country.

Tools for primary caregivers

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) was developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun[29] to measure positive changes experienced by people after major life stressors. This inventory is a self-report scale which contains 21 items and has five subdimensions including “new possibilities,” “relationship to others,” “personal strength,” “spiritual change,” and “appreciation of life.” Items are rated on a 6-point scale (0 = I did not experience this change, 5 = I experienced this change to a very great degree). High scores mean that the person has more growth after traumatic experience. Turkish version of the inventory made by Kilic[30] was used in this study.

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support

This scale which evaluates perceived social support in three dimensions as perceived support from friends, family, and significant others was developed by Zimet et al.[31] The scale contains 12 items and every item is ranked between 1 and 7 points. The highest score of the scale is 84 points and higher scores point out increase in social support. The scale was adjusted to Turkish, and validity and reliability studies were done by Eker et al.[32] through including different sample groups.

Ways of coping inventory

It was developed by Lazarus et al.[33] and was revised to obtain a 66-item questionnaire which contains two subdimensions as problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Karanci et al.[34] removed some items from the scale and they used the 61-item, 3-ranked scale to investigate the relationship between the ways of coping and psychological stress in a preliminary study of a research performed with earthquake victims. Finally, Kesimci[35] developed a 42-item scale with four factors in a study performed with cancer patients. Kesimci[35] determined the factors as fatalistic coping, optimistic coping, problem-focused coping, and desperate coping. This 42-item scale with four factors was used in the present study.

Basic personality traits inventory

In addition to factors which represent the five basic personality dimensions agreeable with literature, Gençöz and Öcül[36] obtained a factor that represents negative personality traits agreeable with literature in this inventory. They constituted “Basic Personality Traits Inventory” for Turkish culture with 45 adjectives chosen among adjectives that have the highest factor loadings obtained from these six factors. The inventory is a Likert-type, 45-item scale, in which each item is scored between 1 and 5 points. The highest scores obtained from the six subfactors of inventory were divided as conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, extraversion, and negative valence points out prominence in related personality trait.

Religious orientation scale

This scale was developed at first by Allport and Ross.[37] This scale has two subdomains named as internal and external religiousness. Nine items of the scale – 1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16, 19 – measure internal religiousness, whereas the remaining 11 items – 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20 – measure external religiousness. The scale is a self-reported 5-point Likert-type scale (1 - absolutely invalid, 2 - invalid, 3 - not sure, 4 - valid, and 5 - absolutely valid). Internal religiousness subdomain of the scale scored between 9 and 45 whereas external religiousness subdomain scored between 11 and 55. Higher scores mean higher level of religiousness.[38]

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, frequency, and ratio values were used in definitive statistics of data. Distribution of variables was measured with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used in quantitative analysis of data. Spearman's correlation analysis was used in the determination of correlation between variables. Linear regression analysis was used in the determination of predictors of PTG.

RESULTS

The study was performed on 109 schizophrenia patients and their 109 caregivers. Twenty-eight patients were women (25.7%) and 81 patients were men (74.3%). Mean age was 43.0 ± 13.4 years, mean duration of disease was 17.0 ± 10.6 years, and mean duration of education was 7.4 ± 3.5 years in patients. Percentage of literate and primary school graduate patients was 67.9% (n = 74). Twenty-two patients (20.2%) were married, 73 patients (67.0%) were single, and 14 patients (12.8%) were widowed. Ninety-one patients (83.5%) were not working. A history of homicidal behavior, suicidal behavior, and hospitalization was reported among 48 (44.0%), 33 (30.3%), and 103 (94.5%) patients, respectively. Mean number of hospitalization of patients (in other words, how many times the hospitalization was required) was 5.4 ± 6.3 (min–max: 0–42). Sixty-nine caregivers were women (63.3%). Mean age was 52.2 ± 13.2 years, mean duration of caregiving was 14.6 ± 10.2 years, and mean duration of education was 7.0 ± 3.8 years in caregiver group. The number of literate and primary school graduate caregivers was 81 (74.4%). Thirty-three caregivers (30.3%) were mothers, 14 caregivers (12.8%) were spouses, 10 caregivers (9.2%) were children, 18 caregivers (16.5%) were fathers, and 31 caregivers (28.4%) were siblings. The number of caregivers working was 29 (26.6%) and number of married was 67 (61.5%). The number of individuals who had a history of physical illness, psychiatric disorder, and were giving care to another person was 36 (33.0%), 14 (12.8%), and 24 (22.0%), respectively.

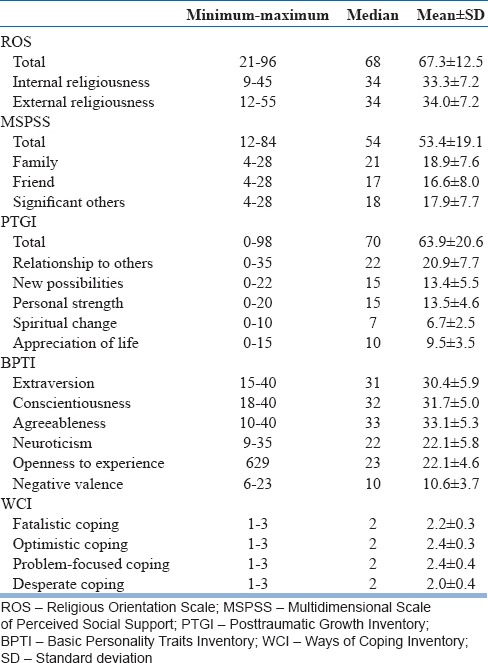

Scores of the scales applied to caregivers are summarized in Table 1. PTGI total score was found to be 63.9 ± 20.6.

Table 1.

Scores of the scales applied to primary caregivers

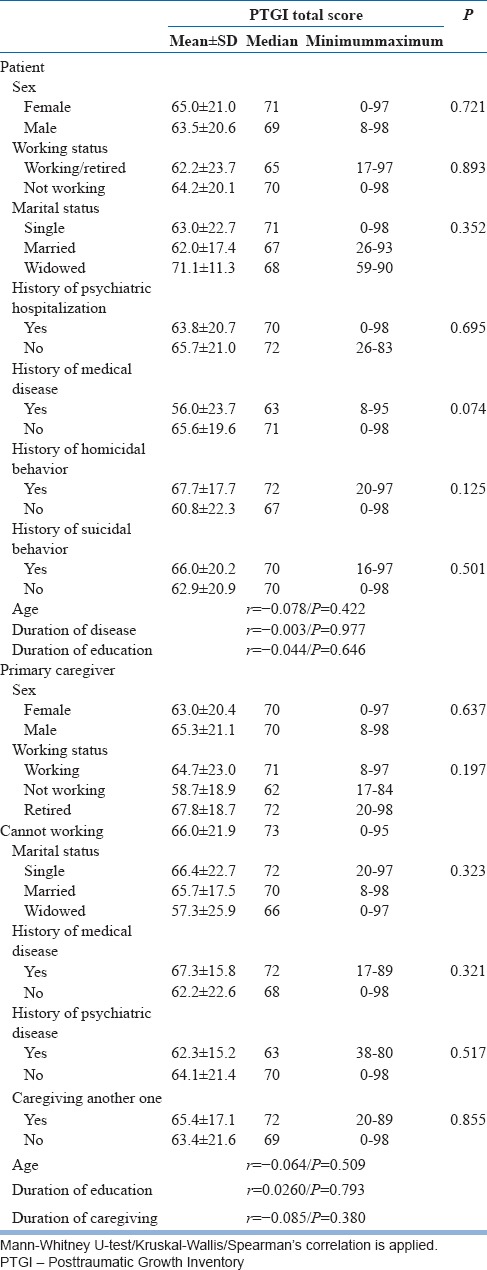

PTGI scores did not differ in terms of sociodemographic (sex, working status, marital status, age, and duration of education) and clinical (presence and number of hospitalization to psychiatry services, duration of disease, history of homicidal or suicidal behavior, and presence of additional diseases) features of patients [Table 2]. PTGI scores did not also differ in terms of sociodemographic (sex, working status, marital status, age, and education status) and clinical (history of physical disease or psychiatric disorder) features and duration of caregiving of primary caregivers [Table 2].

Table 2.

Relationship between sociodemographic and clinical features of patients and primary caregivers and Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Total Score

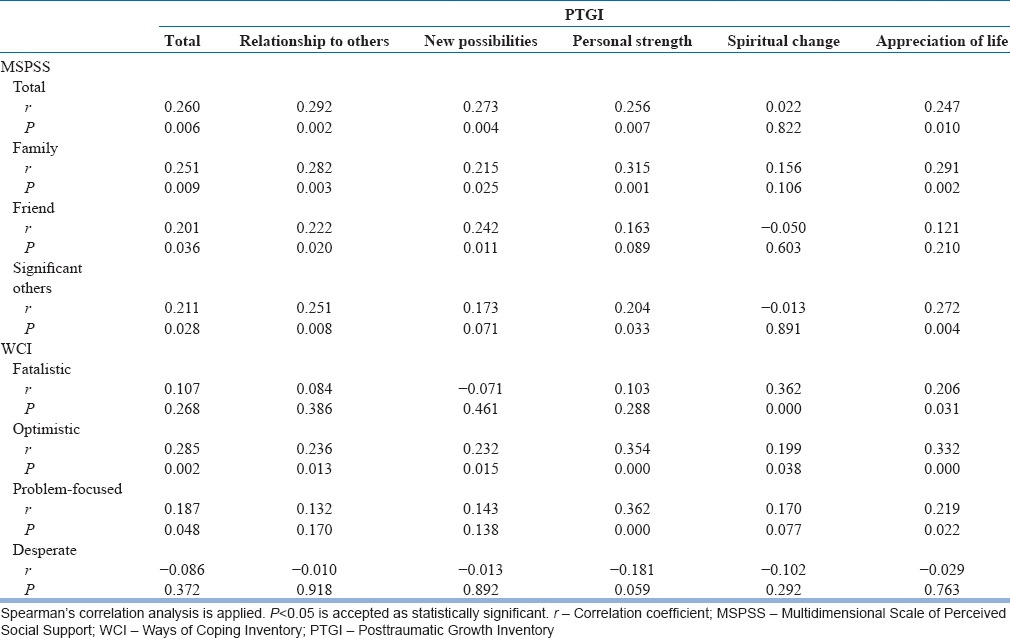

A correlation between PTGI and Ways of Coping Inventory (WCI) and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) scores of primary caregivers is summarized in Table 3. There was a significant positive correlation between total PTGI and MSPSS scores (r = 0.260, P = 0.006) and between total PTGI score and scores of all subdomains of MSPSS (family/friend/significant others) (r = 0.251, P = 0.009/r = 0.201, P = 0.036/r = 0.211, P = 0.028, respectively). Similarly, a significant positive correlation was found between the total score and family subdomain score of MSPSS and all subdomains of PTGI except “spiritual change.” A significant positive correlation between total PTGI scores of caregivers and optimistic and problem-focused coping subscale of WCI (r = 0.285, P = 0.002 and r = 0.187, P = 0.048, respectively) was determined. In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between optimistic coping and all subdomains of PTGI. It was found that problem-focused coping had a positive correlation with “personal strength” subdomain of PTGI (r = 0.362, P = 0.000). Fatalistic coping was found to be related to “spiritual change” and “appreciation of life” subdomains of PTGI (r = 0.362, P = 0.000 and r = 0.206, P = 0.031, respectively).

Table 3.

Correlation between posttraumatic growth and perceived social support and Ways of Coping

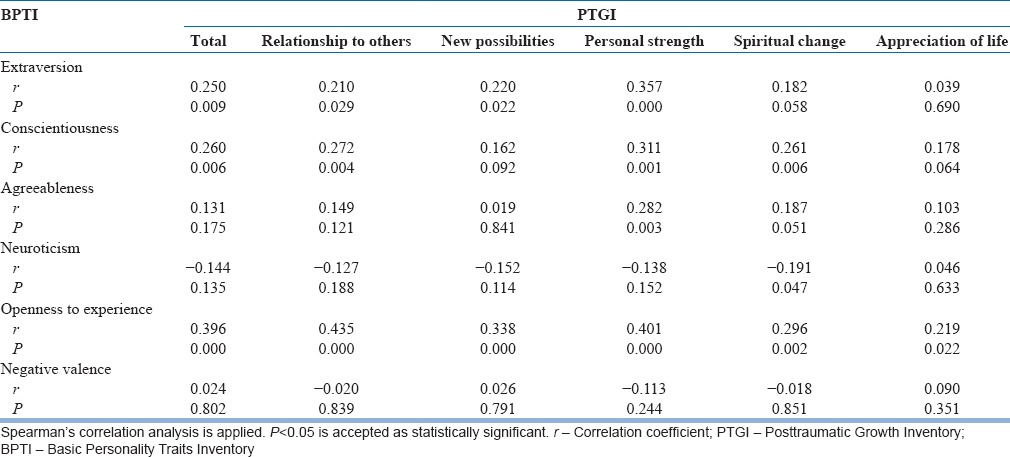

Analyses examining correlation between PTGI and personality traits in primary caregivers are summarized in Table 4. It was found to be a significant positive correlation between total PTGI score and personality traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (r = 0.250, P = 0.009; r = 0.260, P = 0.006; and r = 0.396, P = 0.000, respectively). There was a significant positive correlation between openness to experience and all subdomains of PTGI; between extraversion and “new possibilities,” “relationship to others,” and “personal strength” subdomains; between conscientiousness and “relationship to others,” “personal strength,” and “spiritual change” subdomains; and between agreeableness and “personal strength” subdomains, whereas there was a significant negative correlation between neuroticism and “spiritual change” subdomains.

Table 4.

Correlation between posttraumatic growth and basic personality traits

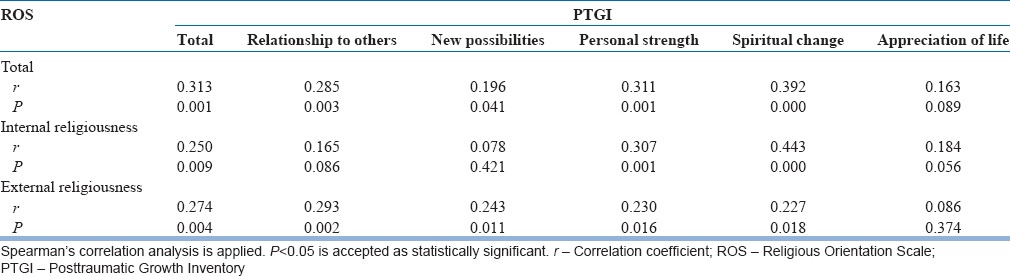

When we examined the correlation between Religious Orientation Scale (ROS) and PTGI scores, a significant positive correlation between total ROS, internal and external religiousness scores, and total PTGI score was determined (r = 0.313, P = 0.001; r = 0.250, P = 0.009; and r = 0.274, P = 0.004, respectively). Similarly, there was a positive significant correlation between total and subdomain scores of ROS and most of the subdomain scores of PTGI [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between Religious Orientation Scale and Posttraumatic Growth Inventory

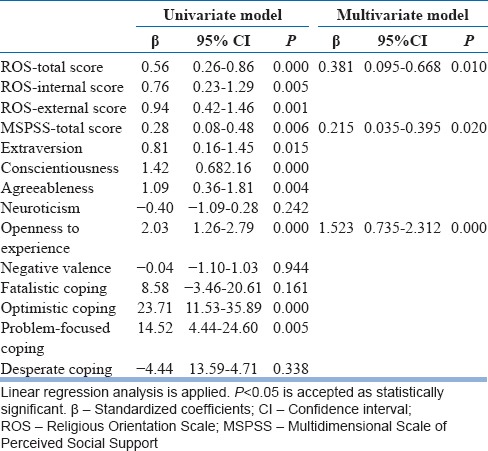

Factors which predict PTG were examined with regression analysis [Table 6]. In the univariate model, total ROS, internal and external religiousness scores, MSPSS scores, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience scores of Basic Personality Traits Inventory (BPTI), and optimistic and problem-focused coping scores of WCI were associated with PTGI. In the multivariate model, we found that ROS, MSPSS total scores, and openness to experience score of BPTI predicted PTG significantly and independently [Table 6].

Table 6.

Regression analysis for factors related to posttraumatic growth

DISCUSSION

In this study, PTG was examined in primary caregivers of schizophrenic patients and it was found that they experienced high level of PTG, consistent with the results of the studies performed with both families of patients with psychiatric disorders[16,17,18] and with caregivers of individuals who have some other severe physical diseases[12,13,19,39] in the literature.

There was no correlation between gender, age, marital status, duration of education, working status of patients and primary caregivers, and PTG. There are different findings related to correlation between sociodemographic features of patients and their caregivers and PTG in the recent studies,[12,40] and this difference is explained as women are more open to traumatic events and its consequences. On the other hand, in some studies, it is found to be difference in PTG in terms of gender.[18] Although studies generally report that younger people experience more PTG,[41,42] there are also some researches which establish no correlation between the two variables in the literature.[15] Also in our study, we did not find any correlation between age and PTG. This result might be originated from relatively high mean age in our caregiver group (52.2 ± 13.3 years). Study results emphasizing the level of education, marital status, working status, and PTG are not related, are outweighing the literature, and results of our study are consistent with these findings.[18,41]

When we examined the relationship between clinical features of the patients (such as duration of disease, history of hospitalization, homicidal or suicidal behavior, and additional physical disease) and PTG, it was found that PTG did not differ in terms of these variables. Ozlu et al.[18] also did not report a relationship between similar clinical features and PTG in their study with caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Although some authors note that clinical features of diseases may be related to PTG,[42] comparison of the findings is impossible as the diagnosis groups of the samples in the studies are considerably different. According to our study, there was no correlation between duration of caregiving and PTG, and we noticed that this variable was not examined in studies that investigate PTG in caregivers of patients with psychiatric disorders.[16,17,18,40] When all these data are evaluated, under the light of the literature, we may suggest that variables including sociodemographic and clinical features of the patients and caregivers and duration of caregiving may not have a notable impact on PTG.

There is a considerable number of studies reporting that social support increases PTG.[17,18,40,43] As consistent with the previous data, we found that perceived social support (total, family, friends, and significant others) was correlated with PTG positively, and furthermore, the total score of MSPSS predicted PTG. Presence of social support, stable and consistent interpersonal relationships (family, friends), and support from a spouse brought with a stable marriage (significant others) increase the development of positive coping skills particularly, and therefore these skills support the development of PTG.[17,43] It was reported that burden of the family was decreased and self-sufficiency was increased by means of family to family support groups performed with families of schizophrenic patients in a study carried out in our country.[44] We suggest that social support as both formal (by psychiatric/psychology professionals) and informal (family, friends, and significant others) can be considered as an important and predictable factor for PTG.

In our study, caregivers using optimistic and problem-focused coping styles more frequently had significantly higher levels of PTG. Furthermore it was found that optimistic and problem-focused coping styles are predictable factors for PTG. Although fatalistic coping is found to be unrelated to total PTGI score, it is correlated to “spiritual change” and “appreciation of life” subdomains of PTGI. Particularly, a positive correlation between problem-focused and optimistic coping styles and PTG is a repeated finding reported by other authors.[17,18,19] In the study of Kesimci et al.,[22] with 132 university students, relationship between desperate, fatalistic, and problem-focused coping styles and PTG was examined and it was reported that fatalistic and problem-focused coping styles were positively related to PTG. Tedeschi and Calhoun[10] reported that traumatic events are perceived and experienced as a challenge against self, future, thoughts, and cognitions about the world of the patient. Trauma is fairly like an earthquake that shakes the basic schema, belief, and aims of the individual. According to the theories of the authors described as cognitive model of PTG, the course of cognitive evaluation and processing of the trauma affect the development of PTG, and a new cognitive construct develops. In the process of this cognitive redevelopment, coping styles (particularly optimistic and problem-focusing) used become very important.[10] This finding is essential in terms of studies to develop new intervention programs (family, psycho-education, and social skill groups) performed to increase PTG. All coping styles, particularly problem-focused coping, are teachable and improvable abilities.[19]

One of the important variables predicting PTG is personality traits.[10,17,45] Particularly, personality traits including openness to experience, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness are personality traits suggested to be related to PTG.[17,45] As supporting these findings, in our study, it is found that openness to experience, extraversion, and conscientiousness are found to be positively correlated with PTG, and also determined as predictors for PTG. Particularly, openness to experience is found to predict PTG independently. Agreeableness is found as correlated to “personal strength” positively. Neuroticism is correlated to “spiritual change” domain of PTGI negatively. Extraversion can help an individual to constitute a supportive environment wherein the individual can make sense of the traumatic events experienced. Similarly, it is suggested that individuals who are extraverted seek social support more frequently and their abilities of problem-solving and cognitive redevelopment are much better.[46] Conscientiousness is also a personality trait that is related to abilities of problem-solving and cognitive redevelopment as similar to extraversion.[46] For this reason, it is comprehensible that, in people who have high conscientiousness levels, the course of processing the traumatic event will accelerate, and coping with the event directly will be more preferable than avoidance.[45] It is known that agreeableness characterized by trust, altruism, compatibility, and sensibility is related to both perceived and received social support.[47] It is reported that individuals who have high agreeableness experience more PTG as espousing the traumatic event more easily and seeking more social support.[45] As neuroticism is mostly related to avoiding type coping, it can disturb the course of the processing of traumatic event which is considerably important for the development of PTG.[45,46] As similar to results of our study, Karanci et al.[45] reported negative correlation between neuroticism and “spiritual change” subdomains of PTG. Openness to experience is a personality trait which is associated with being interested in new situations, experiences, and thoughts.[45] When it is considered that cognitive processing and redevelopment are essential for PTG,[10] we can suggest that individuals who are more open to experience are more ready to process traumatic event and its meaning cognitively.[45] When all findings are evaluated under the light of the previous data, we can suggest that personality traits such as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience have an increasing impact on PTG.

Shaw et al.[26] who reviewed 11 studies systematically researching the relationship between religion, religiosity, and PTG reported three findings. First, though not always but usually, religion and religiosity are beneficial to people for coping with the consequences of trauma. Second, traumatic events can conclude with deepening of religion and spirituality. Third, positive religious coping, religious openness, religious participation, and internal religiosity are typically associated with PTG. Elci[25] reported that religious faithfulness is one of the factors important for predicting PTG in his study with autistic children and their parents. In a recent study performed with 3157 veterans, religiousness was considered in three domains (participation to religious ceremonies, personal religious activities, and internal religiosity) to evaluate its relationship with PTG and it was found that each of the three domains is significantly related to each subdomain of PTG positively.[48] In our study, there was a positive and significant correlation between total ROS score, internal and external religiousness subdomain scores and total PTGI score, and most of the subdomain scores of PTGI. In addition, in our study, total, internal, and external religiousness scores of ROS were found to be predictors for PTG. Total ROS score predicts PTG independently. Many factors including providing a supportive social environment by religious groups, one kind of meditation task of the time spent during religious worship and pray, suggestions of religious doctrines, and holy writs about traumatic experiences in a convicting manner have a positive impact on relation between religiosity and PTG. Association between PTG and religiosity is also found in the study of Currier et al.[49] and it is concluded that religious way of coping and participation in religious meetings and organizations predict PTG at most, but it was noted that PTG can be effected negatively in one who use negative way of religious coping (like interpretation of the event as a punishment given by the God).

One of the limitations of our study is its cross-sectional design. For this reason, it is hard to construct a causational relation between domains found to be correlated. Most of the patients in our study are male in gender (75.3%). Caregivers of both inpatients and outpatients were enrolled in the study, but inpatients are all male patients as the researchers collecting data are working in a clinic of male patients only. The caregivers were largely women in gender (63.3%). This can be evaluated as a limitation. However, we thought that this result is related to Turkish sociocultural structure. In Turkey, the responsibility of caregiving generally belongs to women culturally. Although it was found that gender of the patient and caregiver was not related with PTG, it limits the outcomes of the study in terms of homogeneity of the group. Patients enrolled in the study are cases treated in psychiatry clinics of Bakırköy Prof. Dr. Mazhar Osman Research and Training Hospital for Psychiatry which is the most comprehensive hospital of Turkey for patients with schizophrenia and particularly treatment-resistant cases. For this reason, generalization of the results to all community in Turkey is not possible.

CONCLUSIONS

Personality traits including openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion, religiosity, social support, optimistic and problem-focused coping styles are significant predictors of PTG. Particularly in our country where community-based psychiatric treatments start to become widespread, interventions for improving social support and coping skills should be included in treatment strategies to provide positive changes in families of patients with schizophrenia. There are a limited number of studies that examine growth in caregivers of schizophrenic patients, and to our knowledge, our study is the first comprehensive study which aims to examine all possible factors together suggested to be related to PTG in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Longitudinal studies and studies examining family interventions about this issue will clarify the concept of growth more.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atagun MI, Balaban OD, Atagun Z, Elagoz M, Ozpolat AY. Caregiver burden in chronic diseases. Curr Approaches Psychiatry. 2011;3:513–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gülseren L. Schizophrenia and the family: Difficulties, burdens, emotions, needs. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2002;13:143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gülseren L, Cam B, Karakoç B, Yigit T, Danaci AE, Cubukçuoglu Z, et al. The perceived burden of care and its correlates in schizophrenia. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2010;21:203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jyothi DU, Ali S, Chaitanya D, Chiranjeevi M. Caregiving burden among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia – A prospective cross sectional study. IAJPR. 2015;5:1681–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bademli K, Cetinkaya Duman Z. Family to family support programs for the caregivers of schizophrenia patients: A systematic review. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011;22:255–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsh DT, Johnson DL. The family experience of mental illness: İmplications for intervention. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1997;28:229–37. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenzie EJ. The Experience of Family Members Living with a Relative with Schizophrenia. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Calgary. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiens SE, Daniluk JC. Love, loss, and learning: The experiences of fathers who have children diagnosed with schizophrenia. J Couns Dev. 2009;87:339–48. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. Facilitating posttraumatic growth: A clinician's guide. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMillen JC, Smith EM, Fisher RH. Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:733–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss T. Correlates of posttraumatic growth in married breast cancer survivors. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23:733–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore AM, Gamblin TC, Geller DA, Youssef MN, Hoffman KE, Gemmell L, et al. A prospective study of posttraumatic growth as assessed by self-report and family caregiver in the context of advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2011;20:479–87. doi: 10.1002/pon.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul MS, Berger R, Berlow N, Rovner-Ferguson H, Figlerski L, Gardner S, et al. Posttraumatic growth and social support in individuals with infertility. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:133–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Schroevers MJ, Somsen GA. Post-traumatic growth after a myocardial infarction: A matter of personality, psychological health, or cognitive coping? J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:270–7. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders A, Szymanski K. Siblings of people diagnosed with a mental disorder and posttraumatic growth. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:554–9. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morton RD, White MJ, Young RM. Posttraumatic growth in family members living with a relative diagnosed with schizophrenia. J Loss Trauma. 2015;20:229–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozlu A, Yildiz M, Aker T. Post traumatic growth and related factors in caregivers of schizophrenia patients. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2010;11:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loiselle KA, Devine KA, Reed-Knight B, Blount RL. Posttraumatic growth associated with a relative's serious illness. Fam Syst Health. 2011;29:64–72. doi: 10.1037/a0023043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheikh AI. Posttraumatic growth in the context of heart disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11:265–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karanci NA, Acarturk C. Post-traumatic growth among Marmara earthquake survivors involved in disaster preparedness as volunteers. Traumatology. 2005;11:307–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesimci A, Goral FS, Gencoz T. Determinants of stress-related growth: Gender, stressfulness of the event, and coping strategies. Curr Psychol. 2005;24:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prati G, Pietrantoni L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. J Loss Trauma. 2009;14:364–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milam J. Posttraumatic growth and HIV disease progression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:817–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elci O. Ankara: Doctoral Dissertation, Middle East Technical University; 2004. Predictive Values of Social Support, Coping Styles and Stress Level in Posttraumatic Growth and Burnout Levels among the Parents of Children with Autism. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw A, Joseph S, Linley PA. Religion, spirituality, and posttraumatic growth: A systematic review. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2005;8:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Washington, D.C, London: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis Disorders (SCID-I) Clinical Version. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corapcioglu A, Aydemir O, Yildiz M, Esen A, Koroglu E. Ankara: Hekimler Yayın Birliǧi; 1999. Structured Clinical İnterview for DSM IV (SCID), Turkish Version. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth ınventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:455–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilic C. A Different Dimension of Trauma: Posttraumatic Growth. Predictors of Posttraumatic Growth in Earthquake Victims. International Trauma Meetings IV. 01-04 December, İstanbul, Turkey. 2005:123–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley KG. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eker D, Arkar H, Yaldız H. Factorial structure, validity, and reliability of revised form of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2001;12:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes. The problem of confounded measures. Am Psychol. 1985;40:770–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karanci NA, Alkan N, Aksit B, Sucuoglu H, Balta E. Gender differences in psychological distress, coping, social support, and related variables following the 1995 Dinar (Turkey) earthquake. N Am J Psychol. 1999;2:189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kesimci A. Unpublished Master Thesis. Ankara: Middle East Technical University; 2003. Perceived Social Support, Coping Strategies and Stress-Related Growth as Predictors of Depression and Hopelessness in Breast Cancer Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gençöz T, Öcül Ö. Examination of personality characteristics in a Turkish sample: Development of Basic Personality Traits Inventory. J Gen Psychol. 2012;139:194–216. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2012.686932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967;5:432–43. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.5.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonmez OA. Religiosity, Self-Monitoring and Political Participation: A Research on University Students, Doctoral Dissertation, Middle East Technical Unıversıty. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teixeira RJ, Pereira MG. Factors contributing to posttraumatic growth and its buffering effect in adult children of cancer patients undergoing treatment. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013;31:235–65. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2013.778932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen FP, Greenberg JS. A positive aspect of caregiving: The influence of social support on caregiving gains for family members of relatives with schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:423–35. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000040656.89143.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barskova T, Oesterreich R. Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1709–33. doi: 10.1080/09638280902738441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidarzadeh M, Rassouli M, Shahbolaghi FM, Majd HA, Karam AM, Mirzaee H, et al. Posttraumatic growth and its dimensions in patients with cancer. Middle East J Cancer. 2014;5:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajandram RK, Jenewein J, McGrath C, Zwahlen RA. Coping processes relevant to posttraumatic growth: An evidence-based review. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:583–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yildirim A, Buzlu S, Hacihasanoglu Asilar R, Camcioglu TH, Erdiman S, Ekinci M. The effect of family-to-family support programs provided for families of schizophrenic patients on information about illness, family burden and self-efficacy. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2014;25:31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karanci AN, Isikli S, Aker AT, Gül EI, Erkan BB, Ozkol H, et al. Personality, posttraumatic stress and trauma type: Factors contributing to posttraumatic growth and its domains in a Turkish community sample. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3:17303. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connor-Smith JK, Flachsbart C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93:1080–107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong EM, Bishop GD, Diong SM, Enkelmann HC, Why YP, Ang J, et al. Social support and personality among male police officers in Singapore. Pers Individ Dif. 2004;36:109–23. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai J, El-Gabalawy R, Sledge WH, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Post-traumatic growth among veterans in the USA: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychol Med. 2015;45:165–79. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Currier JM, Mallot J, Martinez TE, Sandy C, Neimeyer RA. Bereavement, religion, and posttraumatic growth: A matched control group investigation. Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2013;5:69–77. [Google Scholar]