Abstract

Aims:

The aim is to study stress among medical students and the relationship of stress to the year of study and gender.

Materials and Methods:

A single-point, cross-sectional, observational study of students of a medical university in North India divided on the basis of the semester of their course. The study was done using the higher education stress inventory.

Results:

A total of 251 students were included in the study. Worry about future endurance and capacity was rated the highest by the final year students while faculty shortcomings and insufficient feedback were rated highest by the 2nd-year students and financial concerns the highest by the 1st-year students. Males rated financial concerns higher than females.

Discussion:

The study would provide insight to the university authorities to make remedies based on the expectations and feedback of the students.

Conclusion:

the current study shows that stress amongst medical students is a dynamic process as the reasons of stress vary depending on the stage of curriculum. The college/university administration can mitigate this by taking appropriate steps as needed

Keywords: Medical education, medical students, stress

INTRODUCTION

One would expect medical students to be better off than their peers in other walks of life when it comes to health, and this does hold true to certain extent as far as medical ailments are concerned.[1] When we look at stress and anxiety, however, this particular population seems to be on the receiving end of the spectrum. Multiple studies have found significantly high-stress levels in medical students and the high stress has been reported from multiple countries, spanning different continents.[2,3,4,5,6] This indicates to certain extent that high stress among medical students is a phenomenon that transcends sociocultural factors, economic status, course patterns, and the alike. Studies done in India are no different and have shown significant morbidity with stress in medical students.[7,8,9,10,11,12] Self-rated depression is also found to be significantly higher in Indian medical students.[13] The current study was done to evaluate the major factors causing stress to medical students in different stages of their course at a North Indian medical university.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was a single-point, cross-sectional, observational study that involved administration of semi-structured pro forma for demographic details and higher education stress inventory (HESI);[14] it is a scale that has been inspired by the Percieved Medical School Stress Scale by Vitiliano et al. but is more comprehensive and is also applicable to other higher educational settings than medical setups to allow scope for comparisons to be drawn among students of different disciplines. It comprises 33 statements indicating the presence or absence of stressful aspects, to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The scale measures the stress in seven domains, i.e. worries about future endurance and competence (WFEC), nonsupportive climate, faculty shortcomings, workload, insufficient feedback, low commitment, and financial concerns. Permission of the original authors (Marie et al.) was taken to use the HESI. The sample was drawn from medical undergraduate students of the university through systematic randomized sampling. Every third student from the list of students from a batch was approached for participation. Four current batches (II semester, IV semester, VI semester, and VIII semester which stand for 1–4th year, respectively) in different stages of their course were used to draw sample. The Indian medical graduation is divided into nine semesters followed by 1 year of compulsory rotating internship. Confidentiality was maintained using a coded key on forms in place of identifying details, to avoid getting socially appropriate responses from the students. Those with a prior history of psychiatric illness, current psychotropic drug use, and physical handicap or with any chronic illness were excluded as the study aimed to focus on the course as source of stress. The participants were allowed up to 2 weeks to complete the questionnaires if a participant did not return the form by then or if she/he opted out of the study by not giving/withdrawing consent, the participant was dropped from the study.

Results were analyzed using Windows by GraphPad Software Inc. The groups were compared using cross-tabulation. Differences in score between stages of course were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and between genders by independent t-test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

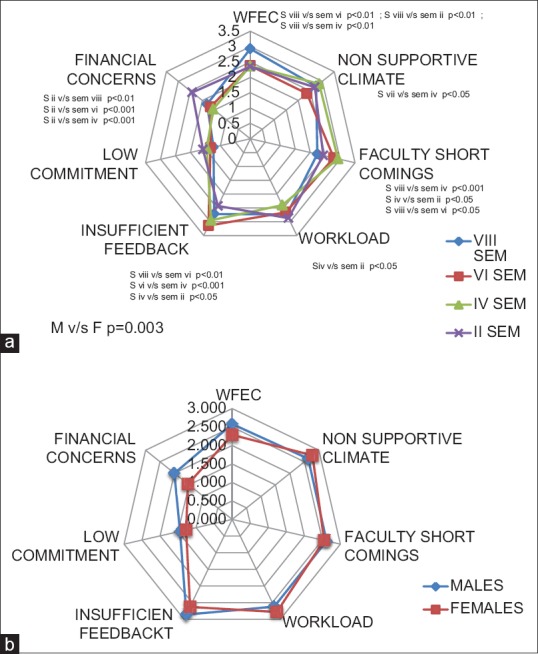

A total of 260 students were approached, and 251 were included in the study. The groups based on the stage of curricula and genders were comparable at baseline. The results of the stress factor scores are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stress scores (a) Stress across study years. (b) Stress across gender

WFEC was found to be steadily increasing with the year of curricula with highest rating by the VIII semester (final year) (year 4 vs. year 3, year 2, and year 1 all P < 0.01). This was similar to results in Swedish study.[14] Similar results have been found in studies on Indian medical students where academic-related stressors have been rated higher than interpersonal stressors.[7,8] In another Indian study, more than 90% of the studied samples reported feeling significantly stressed with much high rating for “fear of poor performance.”[10] Similarly, higher ratings in students of advanced semesters rather than initial ones have been observed in India.[9] One factor for this high rating can be the fact that after putting 5½ years of one's life in medical training, future again depends on a highly competitive entrance examination that decides the future of the graduate, not to mention the highly demanding nature of the residency programs throughout the country. Since interns were not a part of the study, it cannot be said whether the worry increased significantly in the period immediately before taking the examinations.

The perceived lack of feedback was high at all stages of the education; the division, however, was interesting in that the IV semester students gave the highest rating to the factor and lowest were the VI semester students (P < 0.001). This may be viewed as a feedback of the existing academic structure of the university. The curriculum of the 2nd year is spread over three semesters according to the Indian system and includes subjects of pathology, microbiology, forensic medicine, and pharmacology. In our university, the system of examination at this stage involves two examinations in close proximity to each other towards the end of the year, and differs from the other medical schools of country in having done away with more common semester system of examinations; the students also have introductory rotations in the clinical departments of the university along with senior batches, with majority of the clinical teaching and activities oriented for the latter; the same students, however, come back as seniors following year, and senior batches have reflected a lower rating on the factor. Faculty shortcomings were again found to be very significantly higher in the year 2 students (P = 0.0003) while a high rating was found overall except final year, which gave the lowest ratings to the factor. Feedback and interaction with faculty are indeed critical factor in medical teaching, and high ratings in this area are worrisome. Nonsupportive climate was also rated highest by the year 2 and lowest by year 3; however, the difference was not found to be statistically significant (P > 0.5) except in case of post hoc comparison across year 2 and year 3 (P < 0.05). Workload was rated high among all the groups but significantly higher in the 1st-year students. This may be due to their relative inexperience at handling the life of a medical college. Financial concerns were rated the highest by the 1st-year (II semester) students (P < 0.0001). This could be due to a load of college life on previously unburdened students. It should be mentioned that ours being a government university, students avail of a highly subsidized fees and various aids to financially weaker and other classes. Low commitment was responded with a low rating across the groups with a steady decrease across the senior groups.

The comparison of stress factors across gender did not yield any significant differences except in the area of financial concerns, which were rated higher by the male students.

Limitations

An important factor that needs to be discussed is the possibility of individual attitudes and personality coloring the ratings. These have been found to be a major factor of stress and competence.[15] Any amount of objectivity in a scale constructed to measure stress in educational setting cannot negate these factors. Similarly, life events and ongoing stressors may reflect in the ratings.

No control population was used, so it is impossible to say if the stress levels encountered were actually higher than that exist in any other higher education setting.

Future directions

The findings would help the university to bring about remedial measures based on the needs of the students. Furthermore, similar exercises in different medical schools across the country can shed light if these patterns are similar or different based on the cultural and academic practices of different schools. It would also be worthwhile to compare the stress levels and areas with other higher educational settings.

CONCLUSION

The current study shows that stress amongst medical students is a dynamic process as the stressors keep changing with the year of study and constantly changing expectations of the students and the system. The college/university administration can mitigate this by taking appropriate steps as needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

University's Intramural research fund for undergraduate students.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Carter D, Frank E, Ganzini L, Lyketsos C, et al. Caring for medical students as patients: Access to services and care-seeking practices of 1,027 students at nine medical schools. Collaborative research group on medical student healthcare. Acad Med. 2000;75:272–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusoff MS, Abdul Rahim AF, Yaacob MJ. Prevalence and sources of stress among Universiti Sains Malaysia Medical students. Malays J Med Sci. 2010;17:30–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaikh BT, Kahloon A, Kazmi M, Khalid H, Nawaz K, Khan N, et al. Students, stress and coping strategies: A case of Pakistani medical school. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17:346–53. doi: 10.1080/13576280400002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saipanish R. Stress among medical students in a thai medical school. Med Teach. 2003;25:502–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radcliffe C, Lester H. Perceived stress during undergraduate medical training: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2003;37:32–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firth J. Levels and sources of stress in medical students. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:1177–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6529.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panchu P, Bahuleyan B, Vijayan V. An analysis of the factors leading to stress in Indian medical students. Int J Clin Exp Physiol. 2017;4:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham R, Mahirah Binti Zulkifli E, Soh E, Fan Z, Ning Xin G, Tan J, et al. A Report on Stress among First Year Students in an Indian Medical School. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iqbal S, Gupta S, Venkatarao E. Stress, anxiety and depression among medical undergraduate students and their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:354–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.156571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anuradha R, Dutta R, Raja JD, Sivaprakasam P, Patil AB. Stress and stressors among medical undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study in a private medical college in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Community Med. 2017;42:222–5. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_287_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandi M, Hazra A, Sarkar S, Mondal R, Ghosal MK. Stress and its risk factors in medical students: An observational study from a medical college in India. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Supe AN. A study of stress in medical students at seth G.S. medical college. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar GS, Jain A, Hegde S. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors using beck depression inventory among students of a medical college in Karnataka. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:223–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powis D, Hamilton J, McManus IC. Widening access by changing the criteria for selecting medical students. Teach Teach Educ. 2007;23:1235–45. [Google Scholar]