Abstract

There are changes to the degree of cortical folding from gestation through adolescence into young adulthood. Recent evidence suggests that degree of cortical folding is linked to individual differences in general cognitive ability in healthy adults. However, it is not yet known whether age-related cortical folding changes are related to maturation of specific cognitive abilities in adolescence. To address this, we examined the relationship between frontoparietal cortical folding as measured by a Freesurfer-derived local gyrification index (lGI) and performance on subtests from the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence and scores from Conner’s Continuous Performance Test-II in 241 healthy adolescents (ages 12–25 years). We hypothesized that age-related lGI changes in the frontoparietal cortex would contribute to cognitive development. A secondary goal was to explore if any gyrification-cognition relationships were either test-specific or sex-specific. Consistent with previous studies, our results showed a reduction of frontoparietal local gyrification with age. Also, as predicted, all cognitive test scores (i.e., Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning, the CPT-II Commission, Omission, Variabiltiy, d’) showed age × cognitive ability interaction effects in frontoparietal and temporoparietal brain regions. Mediation analyses confirmed a causal role of age-related cortical folding changes only for CPT-II Commission errors. Taken together, the results support the functional significance of cortical folding, as well as provide the first evidence that cortical folding maturational changes play a role in cognitive development.

Keywords: cortical folding, adolescence, brain development

1. Introduction

Human brain anatomy consists of characteristic folds that form sulci and gyri within the cerebral cortex (see Striedter et al. (2015) for recent review). The degree of cortical folding, or gyrification (Zilles et al., 1989; Zilles et al., 2013), can be measured on scans obtained by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) by the ratio of the total folded cortical surface over the perimeter of the brain (Zilles et al., 1988). Regionally-specific gyrification also can be quantified using 3-dimensional measurements of the ratio of a vertex-based 25 mm radius circular region of interest of folded pial surface to the corresponding surface area of a tight-fitting contour enveloping the cortex’s outer perimeter (Schaer et al., 2008). Such measurements are typically termed local gyrification indices (lGI). Studies that used such approaches have confirmed all brain regions are folded to some extent. Brain regions with the greatest gyrification are found in the prefrontal cortex and temporal-parietal cortex association regions (Zilles et al., 2013). Theories argue that gyrification reflects underlying structural connectivity as evidenced by the association between gyrification and measures of cortical connectivity, both functional (Dauvermann et al., 2012) and structural (Schaer et al., 2013). Cortical folding is believed to be related to more efficient communication as surface area expands in the developing brain (Laughlin and Sejnowski, 2003). Importantly, there is evidence that gyrification undergoes developmental changes. Changes from a lissencephalic brain to more complex gyrencephalic structure begin in utero (Sun, 2014). Although the most striking cortical folding changes occur during the third trimester of pregnancy, gyrification continues to change in different ways throughout the first decades of life. After a peak in toddlerhood, both global and local measures of gyrification in frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices gradually decrease throughout adolescence into the early adult years (Aleman-Gomez et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2014; Mutlu et al., 2013; Raznahan et al., 2011a; Su et al., 2013).

While some researchers seek to understand the underlying neurophysiological processes and resultant biomechanics that cause the cortex to fold or unfold in characteristic ways across development (Bayly, 2014; Striedter et al., 2015; Sun, 2014), an equally important question involves the functional significance of cortical folding and its developmental changes. Inter-species comparison suggests that larger brain surface area yielded by greater overall cortical folding might support the higher intelligence seen in primates and cetaceans (Roth and Dicke, 2005, 2012). Supporting this idea, there is evidence that gyrencephalic malformations are associated with cognitive impairment (Guerrini and Carrozzo, 2001; Guerrini et al., 2003). Emerging research also has found an association between variations in regional gyrification and specific cognitive abilities in adults. Following an early report that lateralization differences in gyrification were linked to executive cognition (Fornito et al., 2004), several studies have asked if local gyrification corresponds with cognitive ability. In one such study, intelligence scores were positively correlated with a curvature-based measure of temporal-occipital lobe regions (Luders et al., 2008). Greater gyrification in adults’ bilateral medial and superior frontal cortex has been linked to better verbal working memory and mental flexibility task performance (Gautam et al., 2015). The most recent study of a large sample found lGI in lateral prefrontal cortex, cingulate, insular cortices, inferior parietal lobule, temporoparietal junction regions, and fusiform gyrus was positively associated with a composite measure of general cognitive ability, or “g” in both samples of healthy adults and of children and adolescents (Gregory et al., 2016).

Collectively these studies most often implicate gyrification in frontal and parietal lobe cortices in relation to cognitive ability. The reasons for these associations between individual differences in local gyrification and cognitive ability are not well understood. Similar brain-behavior relationships have been found in these regions when examining brain activation using functional neuroimaging. Lateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortex form specialized neural networks engaged for various goal-directed cognitive tasks requiring executive oversight and control (Braver, 2012; Dosenbach et al., 2008; Vakhtin et al., 2014; Zanto and Gazzaley, 2013). In particular, lateral prefrontal cortex appears to be a core region in this network, as its functional connectivity and aspects of its structure are important to general cognitive control (Cole et al., 2015; Cole and Schneider, 2007), overall intelligence (Jung and Haier, 2007), and various executive functions (Fuster, 2002; Sakagami and Watanabe, 2007; Yuan and Raz, 2014).

Associations like these raise the possibility that individual differences in local frontoparietal gyrification might causally contribute to gains in specific types of cognitive task performance across development by virtue of neurobiological advantages in brain structure that have yet to be fully described or understood. Adolescent maturation is a useful framework to better understand if gyrification causally contributes to cognitive function because both brain structure and cognitive abilities change in characteristic developmental trajectories. Although executive and attention abilities are at near-adult levels by puberty, numerous studies describe they continue to be refined (Nguyen et al., 2016) and improve in various ways until about ages 15 to 17 (Best, 2010; Murty et al., 2016). These developmental trajectories offer a quasi-experimental context wherein one can determine if gyrification-cognition relationships differ across stages of adolescent cognitive development to see if decreasing regional gyrification has a functional impact on cognitive ability. If local changes to gyrification play a causal role in typical maturational gains, associations between specific frontoparietal gyrification values and cognitive abilities should show a meaningful developmental profile. For instance, there might be a gradual linear increase in the strength of relationships between regional lGI and cognitive test performance throughout adolescent development, ultimately resembling adult profiles. Alternatively, the youngest adolescents might show disorganized relationships between local gyrification and cognitive performance, which could shift around mid-adolescence when cognitive gains typically plateau. Regardless, if adolescent lGI maturation contributes to cognitive development, relationships between regional lGI and cognitive ability should differ across adolescence, and those differences should be causally significant.

This study asked if the normative reduction in cortical gyrification that occurs in many brain regions throughout adolescence contributes to adolescent cognitive maturation. If so, the descriptive results can contribute towards theory-building and hypothesis-generation to better understand the specific neurobiological basis of gyrification-cognition relationships. We tested this developmental hypothesis using a mix of statistical moderation and mediation analyses to examine the relationship between local gyrification and various cognitive tests that quantified verbal and nonverbal intellectual ability, sustained attention, inhibitory control, motor response variability, and perceptual sensitivity. The moderation analyses identified which brain regions had different relationships between cortical gyrification and test performance at different ages, then mediation analyses tested whether gyrification at each regional peak exerted a causal influence on the relationship between age and test performance. It is useful to consider several different cognitive domains to ascertain whether any such maturational relationships between gyrification and test performance are commonly found, or are selective to specific cognitive abilities. A secondary objective was to characterize sex-specific gyrification differences in adolescence, including any influence of sex on gyrification maturation and the relationships between gyrification change and cognitive change. Different brain regions have gyrification sex differences during different developmental periods. Greater gyrification variably has been linked to left lateral prefrontal, occipital and right inferior temporal regions in infant girls (Kim et al., 2016), left paracentral cortex and precuneus cortex in two year-old boys (Li et al., 2014) and right prefrontal cortex in the period of 6 to 30 years old (Mutlu et al., 2013). As previous findings have been so mixed, we made no a priori hypotheses for gyrification sex differences or for interactions of sex and age throughout adolescent-to-young adult development. Instead, we used a statistical inference framework adequate for searching the whole brain. Finally, given increasing recognition of how important it is to replicate prior neuroimaging results (Barch and Yarkoni, 2013), we attempted to confirm regional gyrification decreases from puberty until early adulthood observed in prior studies (Klein et al., 2014; Mutlu et al., 2013; Raznahan et al., 2011b) and the association of frontoparietal gyrification with individual differences in overall intelligence and general cognitive ability found in adults (Gregory et al., 2016; Luders et al., 2008).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 244 healthy adolescents and young adults with no history of neurological or psychological illness collected from two separate NIMH-funded neuroimaging studies R01MH080956 (n = 106) and R01MH081969 (n = 138) performed at the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center. Among them, three participants having poor quality were not included (see below for more details about quality control). Thus, a final sample was 241 healthy participants (age range 12–24 years, mean 17.38 (± 3.33), 116 females). No participants were left-handed. Participants were recruited by community advertisements. Informed consent for study participant and parental permission were obtained both from the participants and a parent. The Hartford Hospital Institutional Review Board approved all consents and study procedures. The participants’ lack of psychiatric diagnoses was confirmed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Paus et al. (2008) using standard administration guidelines. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by trained staff. Diagnostic decisions were made in weekly consensus meetings supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist with over 14 years of experience using the K-SADS-PL (MCS).

2.2. MRI Data collection

All participants were scanned at the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center at Hartford Hospital using a Siemens 3T Allegra MRI machine. On the MRI day, all participants tested negative on a urine screen for marijuana, cocaine and heroin. T1-weighted brain structure images were collected using a 3D MPRAGE pulse sequence: repetition time TR=2300 ms, echo time TE=2.74 ms, TI=900ms, flip angle = 8°, matrix=176×256×176, voxel size=1×1×1 mm, pixel bandwidth = 190 Hz.

2.3. Image Processing

Brain structure images were prepared for analysis by first correcting for the estimated MRI bias-field using SPM software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/) followed by noise reduction using FSL SUSAN filtering software (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/). We then performed anatomical reconstruction of the cortical surfaces using the FreeSurfer v5.0 image analysis suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). We followed typical FreeSurfer surface-based cortical reconstruction and analysis, which are validated procedures used in numerous previous studies (Kaufman et al., 1997). The reconstruction estimated the white surface, gray/white matter interface, and the pial surface via two-dimensional mesh of triangular elements comprised of >100,000 vertices per hemisphere. The estimated white and pial surfaces were manually corrected for inconsistencies by visual inspection and addition of control points where necessary to aid gray and white matter differentiation. Estimated total intracranial volume (ICV) derived from the FreeSurfer pipeline (Han et al., 2006; Hyatt et al., 2012; Kuperberg et al., 2003; Rosas et al., 2002) for each participant also was obtained.

2.4. Quality control

Image quality was visually inspected using three methods: 1) One of authors (CJH) examined the original MRI voxel-based images for obvious ringing or ghosting due to subject movement, or signal dropouts in the images etc., then, 2) examined the fit of the FreeSurfer-calculated white and pial surfaces using TkMedit, a volume visualizer by viewing the axial slices (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/tkmedit) and finally, 3) examined the quality of the final FreeSurfer rendered three-dimensional surfaces (pial and inflated) for both the right and left hemispheres for each subject. Out of 244 participants, two participants had visible head motion artifacts and one participant had poor reconstruction due to noise and lGI calculation failed. Thus, these three participants were not included in the main analyses.

2.5. Local Gyrification Index (lGI)

Estimation of vertex-wise lGI values for each participant (Buckner et al., 2004) was implemented in FreeSurfer. The lGI is a surface-based and three-dimensional method, which measures the extent of cortex buried within the sulcal folds at each pial surface location (Schaer et al., 2008). Prior to group analysis, each participant’s data were resampled into a common anatomical space (fsaverage). Surface-based measurements of the lGI for all participants were smoothed using a 5-mm Gaussian kernel.

2.6. Cognitive Measures

The neurocognitive test batteries from the two NIH-funded protocols shared the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Schaer et al. (2008) and the Conner’s Continuous Performance Test-II (Corporation, 2004). The WASI included the Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests to provide estimates of verbal and nonverbal IQ, respectively. The CPT-II (Conners, 2005) is a 14-minute normed computerized test consisting of six blocks that assesses various types of cognitive abilities. It yields variables designed to measure several specific cognitive processes. In current study, dependent variables included errors of Omission (sustained attention), Commission (inhibitory control), motor response Variability, and the d’ signal detection parameter (detectability). These variables of the CPT-II have been commonly used in many previous studies (Busse and Whiteside, 2012; Fasmer et al., 2016; Hervey et al., 2006; Hurks et al., 2005; Lange et al., 2013; Lucke et al., 2015). Raw scores were used instead of norm-referenced scores because we planned to include age and sex into all study analyses to statistically account for variance related to these factors. One participant’ Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning raw scores were missing. Table 1 lists participants’ neurocognitive performance.

Table 1.

Sample Neurocognitive Performance

| Healthy adolescents (N = 241) |

Pearson r Correlation with Age |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | ||

| WASI | ||

| Vocabulary | 56.71 (±8.81) | .388, p<.001 |

| Matrix Reasoning | 27.70 (±3.75) | .128, p=.047 |

|

| ||

| CPT-II | ||

| Commission | 19.21 (±7.13) | −.243, p<.001 |

| Omission | 5.14 (±7.54) | −.300, p<.001 |

| Variability | 10.58 (±10.49) | −.254, p<.001 |

| d’ | 0.48 (±0.37) | .150, p<.020 |

Note. These values represent raw values. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

One participant had missing data for the Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning scores.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All cognitive test raw scores used as independent variables were z-transformed. Inspection of distribution skewness prompted a log transform of the CPT-II d’ values to better fit statistical assumptions. Each cognitive measure was included in FreeSurfer different offset, different slope (DODS) general linear models (GLM) as prior studies indicated gyrification changes across adolescence are linear only (Mutlu et al., 2013). But to completely rule out the possibility of any non-linear effects of age, we also tested non-linear effects of age and age × cognition interactions on gyrification by including age-squared term in all models tested. We estimated six separate GLM models, each of which used lGI as the dependent measure. Each model examined the main effects of one of the six cognitive variables (i.e., either Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning, Omissions, Commissions, Variability, or d’ test scores) on whole brain lGI. Each GLM included FreeSurfer’s estimate of total intracranial volume (ICV) as a covariate of no interest, as well as age and a dummy-coded sex term. ICV was included because prior studies have found global gyrification is correlated with total brain volume (Conners, 2005) and has relationships with various cognitive abilities and sex (Pietschnig et al., 2015). The age and sex terms both accounted for variance related to these effects and allowed us to test age- or sex-interaction effects with each cognitive measure. Lending confidence to analysis of sex differences, we found that boys and girls Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning raw scores did not statistically differ, suggesting overall intellectual ability was not a global confound to our analyses of specific cognitive test performance. Boys (n=125) mean Vocabulary raw score=57.85 ± 7.69 and mean Matrix Reasoning=28.10 ± 3.74. Girls (n =115) mean Vocabulary=55.97 ± 8.29 and mean Matrix Reasoning=27.29 ± 3.74. With the exception of the ICV and sex (r = .600, p <.001) relationship that reflected a known sex-based brain size difference, our multicolinearity assessment using bivariate Pearson correlation found none of the other regressors were significantly correlated with each other.

To identify specific brain regions with significant lGI effects, we used cluster-wise correction for multiple comparisons from Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations (Pintzka et al., 2015; Royle et al., 2013). Clusters were initially obtained using a p < 0.001 (two-tailed) vertex-wise threshold, and then reported only if they met additional cluster-wise probability of p <0.05 (two-tailed). Though there has been much discussion recently about possible pitfalls of clusterwise inference (Eklund et al. 2016), the use of cluster-determining thresholds of p< .001 have borne out with repeated testing to accurately control Type I/II error rates in of whole brain analyses (Cox et al., 2017; Woo et al., 2014). Although the vertex-wise entry criterion could be considered conservative, the effects that were observed were widespread enough that distinct brain regions were sometimes assigned to the same cluster. This entry-level threshold therefore balanced statistical rigor with specificity in the results. We identified the strongest peaks for clusters showing significant relationships between lGI and study factors. For these, we tabulated cluster number, maximum –log10 (p-value) within each cluster, cluster area size (in mm2), Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates, number of vertices in the cluster, FreeSurfer anatomical region label, and Brodmann area (BA) label, if available.

We were particularly interested in statistical interactions with cognitive performance (e.g., age × cognitive score) because of their implications for our maturation-based hypotheses. For significant age × cognitive score interaction, supplemental analyses using Pearson correlation between peak lGI value and cognitive score were conducted to visualize the relationship between lGI and cognitive score for four age-defined subgroups: 1) early adolescence (ages 12–14, n = 65), mid-adolescence (ages 15–17, n = 87), late-adolescence (age 18–20, n = 47), and post-adolescence (age 21–24, n = 42). Because these were post hoc, the unequal number of participants for each age-defined subgroup was not relevant to the statistical power issue of the initial age × cognitive score interaction tests. These subdivisions not only reflected meaningful developmental periods, they also spanned the full age range of the sample and had sufficient number of observations to depict stable subgroup results. However, such moderation effects only identify brain regions for which the association differs at various ages. To determine if lGI developmental changes might causally influence the well-known relationships between age and cognitive test performance, we conducted mediation analyses for all statistically significant interaction peak effects found in the FreeSurfer analyses. After extracting peak vertex values, regression analyses in SPSS v23 software estimated the t statistic values that represented the effect of each direct a (age predicting lGI) and b (lGI predicting cognitive test performance) pathway. For these regression models, all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were 1.0 indicating no problems with multicolinearity. We then used the partial posterior approach to estimate the indirect effect ab of age on cognitive performance that passes through lGI assuming at reference distribution. Comparison of this approach to other mediation analyses has found that its statistical power is higher than comparable techniques and it satisfactorily controls for Type I error rates. The analyses to obtain mediation p values were implemented using Java-based freeware (Biesanz et al., 2010). Finally, an experiment-wise α adjustment to correct for multiple mediation tests was implemented using False Discovery Rate (Falk and Biesanz, 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Main Effects of Cognitive Ability on Local Gyrification (lGI)

Verbal intelligence as measured by WASI Vocabulary performance was associated with greater local gyrification in the left superior frontal (MNI xyz: −19.9,−3.6,51.8; maximum −log10 (p -value): −5.45, cluster area: 1173.21 mm2) and right fusiform gyri (MNI xyz: 41.3,−50.1,−13.1, BA 37; maximum −log10 (p-value): −4.07, cluster area: 386.34 mm2). No significant clusters were observed regarding the association between Matrix Reasoning scores and the lGI values after correcting for multiple comparisons although some frontoparietal regions’ lGI values were correlated with Matrix Reasoning at uncorrected significance levels. There were also no associations between whole brain lGI and any of the CPT-II variables.

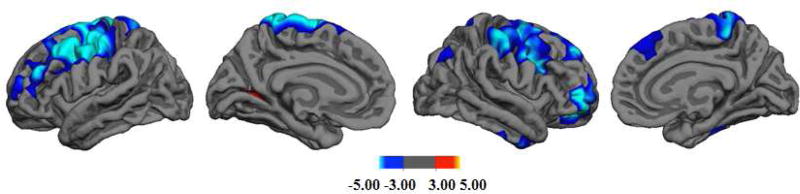

3.2. Main Effects of Age on Local Gyrification (lGI)

Our results confirmed previous studies that found age-related gyrification changes in adolescence. Consistent with previous findings (Gregory et al., 2016; Luders et al., 2008), age was negatively associated with lGI in several clusters in the left middle and right superior frontal gyrus (BA 9), inferior temporal (BA 20) and parietal cortices (BA 39). That is, in older participants, these brain regions showed less cortical folding (see Table 2 and Fig.1), at least, relative to individual intracranial volume adjustments.

Table 2.

Age-related lGI Changes. The maximum –log10(p-value) within the cluster, area size of the cluster (in mm2), Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates, number of vertices, Desikan atlas anatomical label, and Brodmann area (BA) are listed for each peak regional effect.

| Max. −log10 (p-value) |

Area Size (in mm2) |

MNI | Number of vertices |

Anatomical Region | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Left | −9.14 | 11043.57 | −41.1 | 3.2 | 44.8 | 22943 | Caudal middle frontal |

| −4.26 | 435.39 | −23.7 | 51.3 | 16.2 | 597 | Rostral middle frontal | |

| 3.71 | 608.51 | −22.3 | −58 | 7.5 | 1387 | Precuneus | |

| Right | −6.57 | 7963.47 | 20.7 | −7.8 | 56.0 | 17471 | Precentral |

| −6.42 | 2406.79 | 25.0 | 43.7 | −9.9 | 3448 | Lateral orbitofrontal | |

| −5.35 | 1066.30 | 13.7 | 43.4 | 40.0 | 1889 | Superior frontal (BA 9) | |

| −4.55 | 728.96 | 45.4 | −6.8 | −41 | 1128 | Inferior temporal (BA 20) | |

| −3.92 | 669.71 | 32.6 | −66.2 | 29.2 | 1242 | Inferior parietal (BA 39) | |

Fig. 1.

lGI Clusters Associated with Age-related Changes

Note. From left to right: lateral and medial views in the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere.

lGI = Local Gyrification Index. Scale bar represents −log(10)p.

A non-liner effect of age was found only in the left superior parietal cortex (MNI xyz: −15.2, −52.9, 63.6, maximum −log10 (p-value): 5.85, cluster area: 1536.49 mm2) showing a positive association between age2 and lGI values (r = 0.13, p = .03).

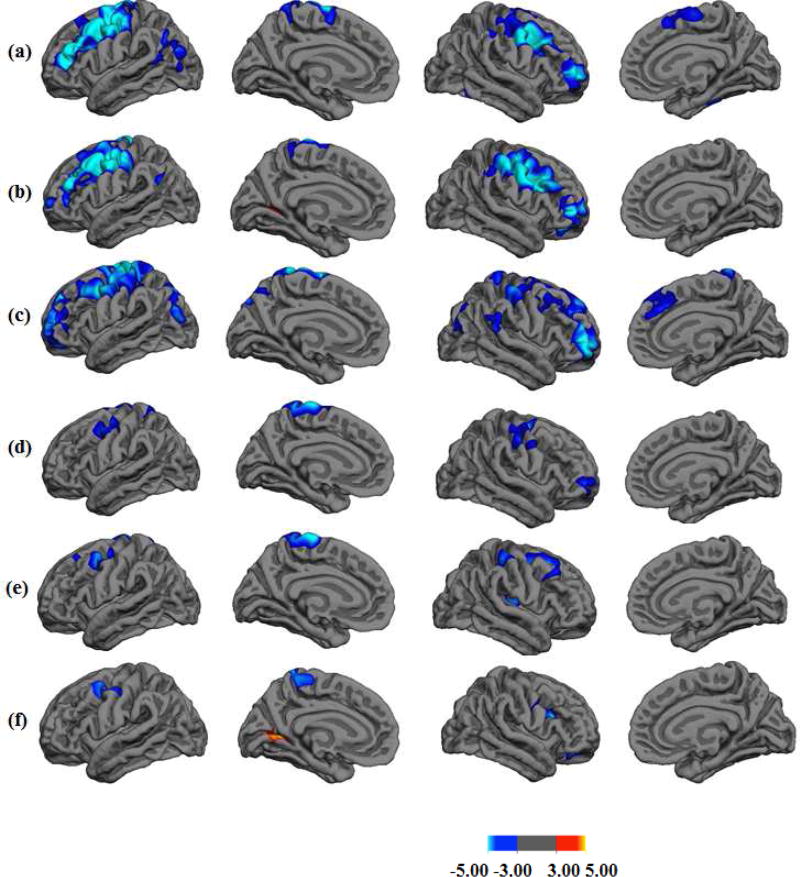

3.3. Interaction Effects of Age × Cognitive Ability on Local Gyrification (lGI)

All cognitive tests that we examined showed age × cognitive ability interaction effects. The brain regions found for each GLM analysis are listed in Table 3. As predicted, many regions in the frontoparietal cortices showed age × cognitive ability interaction effects. In general, there was noteworthy overlap among the different cognitive test results. For instance, the relationship between lGI in left caudal middle frontal gyrus was found to differ with age for all six analyses. All analyses also found age × cognitive ability interaction effects for a cluster that included a medial wall area of left paracentral lobule. The Vocabulary, Matrix Reasoning, and CPT-II Commissions analyses had different relationships with lGI depending on participant age along nearly the full length of bilateral middle frontal gyri and the most dorsal aspects of superior frontal gyri on the lateral brain surface. However, specific differences among different cognitive measures also were observed. For example, only the age × d’ analysis found age-related differences in the relationship between d’ and right pars opercularis lGI. Only Vocabulary and CPT-II Commissions analyses identified medial frontal gyrus/anterior cingulate cortex, left inferior parietal lobule, and right supramarginal gyrus.

Table 3.

Age × Cognitive Test Performance Interaction Effects for lGI. The maximum –log10(p-value) within the cluster, area size of the cluster (in mm2), Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates, number of vertices, Desikan atlas anatomical label, and Brodmann area (BA) are listed for each peak regional effect. For each peak, the Pearson correlation with the cognitive test score is listed separately for age subgroups. The final column lists the p value for the partial posterior mediation analyses.

| Max. −log10 (p-value) |

Area Size (in mm2) |

MNI

|

Number of vertices |

Anatomical Region | Age Subgroups Pearson r | lGI Mediation Effect p |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | 12–14 | 15–17 | 18–20 | 21–24 | ||||||

| Age × Verbal Intelligence (Vocabulary) | ||||||||||||

| Left | −10.72 | 9598.24 | −39.8 | 4.0 | 45.5 | 19232 | Caudal middle frontal (BA6) | .264* | .384** | .160 | .331* | .096 |

| −4.34 | 1484.73 | −39.8 | −75.4 | 24.3 | 2961 | Inferior parietal (BA19) | .133 | .313** | .274 | .267 | .038 | |

| −3.98 | 484.69 | −8.7 | −41.9 | 66.0 | 1181 | Paracentral (BA 7) | .015 | .304** | .105 | .160 | .510 | |

| Right | −7.12 | 5696.84 | 37.4 | 3.8 | 37.5 | 11779 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 8) | .088 | .350** | .247 | .267 | .240 |

| −6.52 | 2001.05 | 28.3 | 48.4 | 2.8 | 2862 | Rostral middle frontal (BA 10) | .126 | .314** | .369* | .092 | .160 | |

| −5.64 | 832.09 | 44.4 | −37.9 | −18.8 | 1535 | Inferior temporal (BA 37) | .178 | .332** | .379** | .239 | .005† | |

| −4.49 | 350.10 | 53.1 | −33.6 | 45.5 | 828 | Supramarginal (BA 40) | .025 | .234* | .187 | .332* | .283 | |

| −4.49 | 1096.65 | 18.5 | 8.9 | 60.9 | 2218 | Superior frontal (BA 6) | −.001 | .416** | .201 | .213 | .175 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age × Nonverbal Intelligence (Matrix Reasoning) | ||||||||||||

| Left | −10.77 | 9601.97 | −41.0 | 3.0 | 44.0 | 18684 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 6) | .009 | .277** | .179 | .208 | .052 |

| −4.12 | 312.88 | −46.8 | −59.0 | 28.3 | 652 | Inferior Parietal (BA 39) | −.042 | .183 | .214 | .277 | .076 | |

| 3.85 | 324.08 | −18.5 | −56.6 | −2.2 | 788 | Lingual (BA 19) | .029 | .035 | −.183 | −.265 | .608 | |

| Right | −7.28 | 7527.75 | 36.7 | 17.7 | 31.9 | 15645 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 9) | −.061 | .321** | .178 | .151 | .071 |

| −5.88 | 2285.96 | 39.1 | 48.9 | 1.4 | 3405 | Rostral middle frontal (BA 10) | −.060 | .214* | .159 | .264 | .154 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age × Commission | ||||||||||||

| Left | −7.20 | 11978.35 | −12.2 | −23.5 | 73.7 | 24298 | Precentral (BA 6) | −.040 | .321** | .126 | .398** | .0002† |

| −4.98 | 746.19 | −16.7 | −76.8 | 44.3 | 1475 | Superior parietal (BA 7) | .152 | .264* | .061 | .230 | .0007† | |

| −4.52 | 1118.17 | −39.8 | −75.1 | 25.3 | 1835 | Inferior parietal (BA 19) | .158 | .358** | .101 | .152 | .0003† | |

| Right | −6.40 | 5473.65 | 35.4 | 51.1 | −4.2 | 8766 | Rostral middle frontal (BA 10) | .060 | .276* | .130 | .378* | .0001† |

| −5.08 | 3164.49 | 17.5 | 2.0 | 63.3 | 7148 | Superior frontal (BA 6) | −.224 | .328** | −.029 | .461** | .0032† | |

| −4.34 | 901.89 | 33.3 | −69.8 | 22.3 | 1604 | Inferior parietal | .077 | .404** | −.042 | .040 | .0009† | |

| −4.12 | 588.87 | 60.7 | −41.4 | 17.4 | 1259 | Supramarginal (BA 22) | .057 | .405** | −.091 | .175 | .002† | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age × Omission | ||||||||||||

| Left | −4.68 | 1278.09 | −9.1 | −22.8 | 73.9 | 2957 | Precentral (BA 6) | −.239 | .134 | .254 | .064 | .051 |

| −4.51 | 2073.53 | −40.8 | 3.4 | 45.2 | 4053 | Caudal middle frontal (BA6) | −.227 | .064 | .141 | −.170 | .975 | |

| Right | −5.88 | 3492.23 | 27.9 | −14.1 | 55.0 | 7682 | Precentral (BA 6) | −.165 | .261* | .312* | −.074 | .256 |

| −4.84 | 1833.91 | 31.5 | 49.5 | 0.5 | 2677 | Orbitofrontal (BA 10) | −.075 | .169 | .056 | −.058 | .229 | |

| −4.23 | 760.40 | 7.3 | −37.8 | 75.4 | 1965 | Postcentral | .014 | .237* | .062 | −.110 | .111 | |

| −4.01 | 384.40 | 13.8 | 41.9 | 40.4 | 604 | Dorsolateral prefrontal (BA 9) | −.144 | .251* | −.169 | .189 | .193 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age × Variability | ||||||||||||

| Left | −5.28 | 939.43 | −6.4 | −18.4 | 71.2 | 2230 | Paracentral (BA 6) | −.027 | .069 | .318* | −.013 | .081 |

| −4.71 | 1300.53 | −35.1 | 0.4 | 47.4 | 2440 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 6) | −.163 | −.036 | .338* | −.251 | .990 | |

| −3.88 | 354.49 | −21.7 | 21.3 | 47.2 | 627 | Superior frontal (BA 8) | −.256* | .174 | .08 | .029 | .474 | |

| Right | −5.29 | 990.06 | 11.3 | −20.3 | 72.6 | 2555 | Precentral (BA 6) | −.092 | .053 | .126 | .213 | .163 |

| −4.98 | 790.97 | 35.7 | 50.6 | −2.5 | 1062 | Rostral middle frontal (BA 10) | .011 | −.127 | .068 | .248 | .326 | |

| −4.35 | 540.95 | 29.1 | −13.8 | 54.1 | 1194 | Precentral | −.140 | .076 | .198 | .124 | .243 | |

| −4.34 | 1574.65 | 37.8 | 4.4 | 39.5 | 3157 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 8) | −.116 | .122 | .204 | .125 | .137 | |

| −3.98 | 648.68 | 13.0 | 30.4 | 52.3 | 1141 | Superior frontal (BA 8) | −.068 | .096 | −.184 | .068 | .474 | |

| −3.96 | 358.76 | 33.1 | −15.3 | 41.0 | 830 | Precentral | −.088 | −.018 | .193 | .028 | .653 | |

| −3.73 | 305.35 | 39.5 | 9.3 | −37.6 | 448 | Temporal pole (BA 38) | .018 | .321** | −.007 | .014 | .018 | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age × d’ | ||||||||||||

| Left | 5.04 | 1125.42 | −19.2 | −65.5 | 0.5 | 2318 | Lingual | −.164 | −.074 | −.163 | −.167 | .066 |

| −4.34 | 508.76 | −15.4 | −44.3 | 70.3 | 1208 | Precuneus (BA 7) | .169 | −.162 | .606** | −.195 | .325 | |

| −3.95 | 745.85 | −38.7 | 6.3 | 53.5 | 2128 | Caudal middle frontal (BA 6) | .124 | −.023 | .165 | −.147 | .601 | |

| Right | −4.74 | 1018.36 | 38.6 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 2121 | Pars opercularis (BA 44) | .272* | .050 | .355* | −.259 | .313 |

| −4.23 | 338.50 | 22.8 | 38.7 | −13.9 | 527 | Lateral orbitofrontal (BA 11) | .161 | −.103 | .141 | .155 | .860 | |

Pearson correlation statistically significant at p < .05 uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Pearson correlation statistically significant at p < .01 uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Statistically significant mediation effect after False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons.

Post hoc inspection of the relationship between lGI and cognitive test performance revealed that significant associations were most often found in the 15–17 year old subgroup. Moreover, these associations were consistent only for WASI Vocabulary and CPT-II Commission errors, but notable for WASI Matrix Reasoning (3 of 5 regions) and CPT-II Omission errors (3 of 6 regions). For other age subgroups and for other tests, the relationship between regional gyrification and test performance relationship was much less strong, rarely reaching a statistical significance (p < .05). This suggests that mid-adolescence is a unique period when cortical folding is more strongly related to select cognitive abilities (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Clusters Showing Interaction Effects of Age by Cognitive Abilities

Note. (a) Verbal score, (b) Matrix Reasoning score, (c) CPT-II Commission, (d) CPT-II Omission, (e) CPT-II Variability, (f) d’

From left to right: lateral and medial views in the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere.

Scale bar represents −log(10)p.

Regarding non-linear age × cognition effects, we found age × d’ interaction effects only in small regions in the left superior parietal and right lateral occipital cortex (MNI xyz: −16.6, −77.3, 43.2, BA7; maximum −log10 (p-value): 5.59, cluster area: 456.36 mm2; MNI xyz: 28.7, −85.4, 13.9; maximum −log10 (p-value): 3.97, cluster area: 339.70 mm2, respectively) (Supplemental Fig.1).

3.4. Main Effect of Sex on Gyrification (lGI)

Overall sex differences in gyrification were observed in only two clusters: left caudal middle frontal cortex (MNI xyz: −39.4,8.0,51.8, BA6; maximum −log10 (p-value): −5.05, cluster area: 457.41 mm2) and right precentral gyrus lGI (MNI xyz: −21.1, −9,54.7; maximum −log10 (p-value): −5.04, cluster area: 687.24 mm2). Boys had greater gyrification in both regions compared to girls.

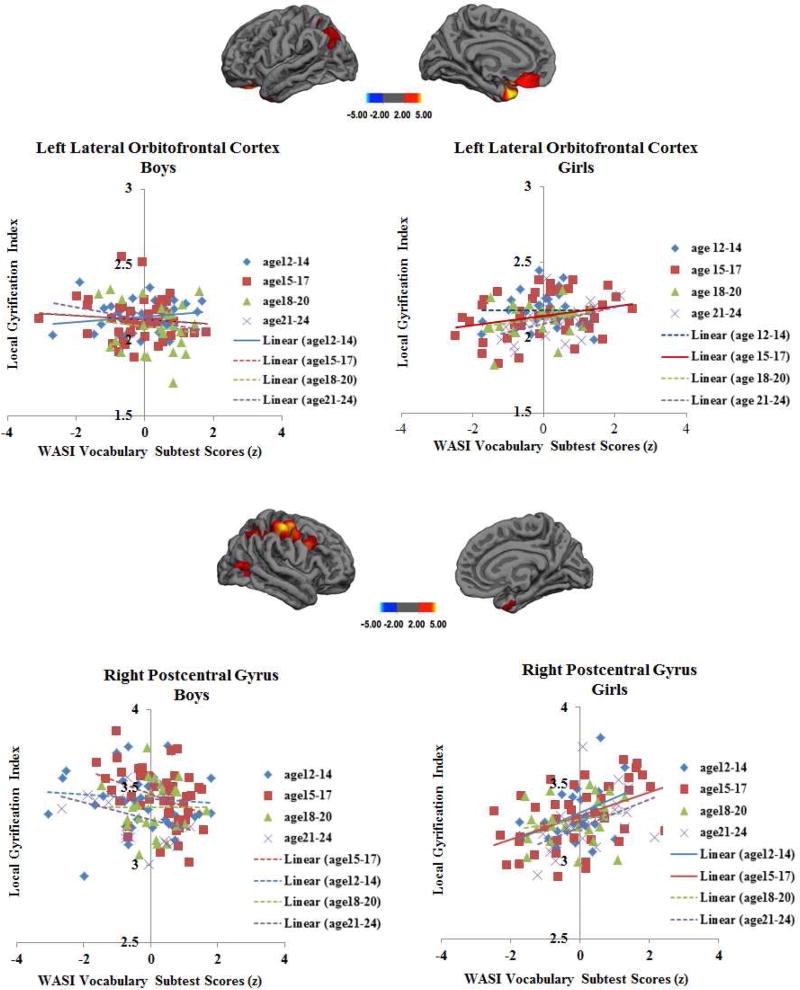

3.5. Interaction Effects of Sex × Cognitive Ability on Local Gyrification (lGI)

We found one cluster in left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (xyz: −17.6, 20.2, −21.4, BA11, maximum −log10 p-value: 4.43, cluster area: 786.03 mm2), and another in right postcentral gyrus (xyz: 50.2, −20.9, 54.3, maximum −log10 p-value: 5.10, cluster area: 1485.38 mm2) showing a sex × Vocabulary interaction effect. None of the analyses examining the interaction of sex with Matrix Reasoning or any of the CPT-II scores found any effects.

Post hoc Pearson correlation analyses indicated that girls showed positive associations between left lateral orbitofrontal cortex and right postcentral gyrus lGI values and Vocabulary test performance (r = .22, p =.016; r = .27, p =.003, respectively), while boys showed negative associations between the same lGI values and Vocabulary scores (r = −.29, p =.001; r = − .31, p .0003, respectively).

3.6. Interaction Effects of Sex × Age × Cognitive Ability on Local Gyrification (lGI)

Boys and girls showed different patterns of age by Vocabulary interaction in the same two clusters in left lateral orbitofrontal cortex and right postcentral gyrus (xyz: −17.7, 19.4, −21.4, maximum −log10 p-value: 3.77, cluster area: 371.30 mm2; xyz: 49.8, −21.0, 55.5, maximum −log10 p-value: 5.10, cluster area: 1532.80 mm2, respectively) that showed sex by Vocabulary interaction effect. According to post hoc Pearson correlation analyses, for girls in 15–17 year old subgroup only, greater Vocabulary scores were significantly associated with greater degree of lGI in the left orbitofrontal cortex (r =0.37, p = .02), while boys in 12–14 year old subgroup only showed an opposite pattern of negative association (r = −0.35, p = .04). In the right postcentral gyrus, girls in 12–14 and 15–17 year old subgroups showed positive associations between Vocabulary scores and lGI (r =0.43, p = .01; r =0.48, p =.002, respectively) whereas boys in any age subgroups did not show significant associations (all ps > .17) (Fig.4).

Fig.4.

Clusters Showing Interaction Effects of Sex by Age by Cognitive Abilities

Note. Dashed and solid lines indicate non-significant and significant associations, respectively.

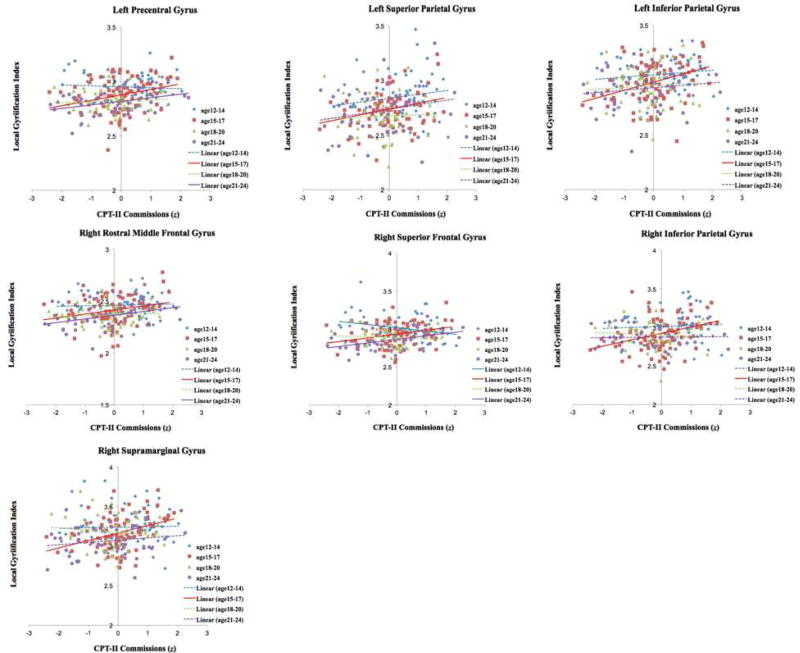

3.7. Mediation Effects for Age × Cognitive Ability Interactions

The last column of Table 3 presents the p values for partial posterior mediation analyses that tested for a causal influence of lGI on the relationship between age and cognitive test performance. After correcting for multiple comparisons, mediation effects were consistently found for the peak brain regions that had a significant interaction between age and the number of CPT-II Commission errors made by the participants. This indicates that age-related changes in local gyrification contribute causally to motor inhibition ability gains seen throughout adolescence. The only other brain region that survived multiple comparisons correction was for WASI Vocabulary, where right inferior temporal gyrus gyrification mediated the relationship between age and Vocabulary test performance. It is worth noting that nearly every cognitive test examined had at least one brain region where lGI exerted a causal influence at p < .05 uncorrected or ‘trend’ levels of significance. However, such effects were sporadic and none survived corrections for multiple comparisons.

To better describe the relationships between age, lGI, and CPT-II Commission errors, we depicted the linear association between lGI and test performance separately for early, mid-, late-and post-adolescence subgroups (Fig. 3). For all regions, the overall association was positive, such that greater lGI (i.e., a less mature profile) was associated with poorer test performance. For most of these regions, the youngest participants (ages 12–14) had no significant relationship between local gyrification and number of Commission errors (average magnitude of the absolute value of the Pearson r statistic for 12–14 year olds = 0.109). In general, the strength of the relationship between lGI and Commission errors showed a sharp increase for the mid-adolescence subgroup (ages 15–17). For instance, this association was significant for all regions examined for the mid-adolescence subgroup (Pearson r values 0.26 to 0.40, p values .01 to .0001), but none of these regions with showed significant relationships between lGI and Commission errors for the early or late adolescent subgroups. At the conclusion of this adolescent-to-young adult developmental period, a few regions (i.e., left precentral, right rostral middle frontal, and right superior frontal gyri) again show a relationship between lGI values and Commission errors. The latter likely reflects the cessation of a developmental process where adult-like individual differences emerge. For Vocabulary performance, we observed a similar adolescent-limited association between right inferior temporal gyrus lGI and word knowledge. The simple association between these was only significant for the mid-adolescent (r = 0.33, p = .002) and late-adolescent (r = 0.38, p = .009) subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Scatter Plots Showing Age by CPT II Commission Errors on the lGI Clusters

Note. Dashed and solid lines indicate non-significant and significant associations, respectively.

3.8. Mediation Effects for Sex × Cognitive Ability Interactions

Neither mediation analysis for right postcentral gyrus (p = .19) or left lateral orbitofrontal gyrus (p = .82) found a significant mediating effect of regional lGI on the relationship between sex and cognitive test performance.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine if normative adolescent reduction in cortical gyrification contributes to adolescent cognitive maturation. We tested this by first examining whether or not the associations between MRI-measured cortical folding metrics and cognitive test performance varied at different ages. Overall, frontoparietal local gyrification decreased with age as seen in several prior studies (Aleman-Gomez et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2014; Mutlu et al., 2013; Raznahan et al., 2011b; Su et al., 2013). As hypothesized, for every cognitive test we examined, the relationships between frontoparietal cortical folding reductions and cognitive abilities changed throughout adolescent development. Specifically, the age × cognitive interaction effects provide evidence that the relationships between local cortical gyrification and sustained attention, inhibitory control, motor response variability, perceptual sensitivity, and both verbal and nonverbal conceptualization abilities differ at different ages during adolescence. These changing brain-behavior relationships were mostly but not exclusively seen in frontoparietal and temporoparietal brain regions where local gyrification values linearly decreased with age and where prior studies show links to individual differences in intellectual ability for healthy adults (Docherty et al., 2015; Gregory et al., 2016) and individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (Lukoshe et al., 2014; Treble et al., 2013). Even though these interaction effects were found for all tests examined and in widespread frontoparietal cortices, statistical mediation analyses showed age-related changes in cortical folding causally influenced only motor response inhibition ability. There were no mediation effects for performance on other types of tests. Therefore, despite widespread changes in the relationship between frontoparietal gyrification and different cognitive abilities across adolescence, these brain changes appear to have a narrow causal impact.

The exact relationships between lGI and cognitive ability at different ages were complex and challenge easy interpretation. Unlike prior adult studies that suggest lGI-cognition relationships could reflect simple individual differences, the functional contribution of gyrification to cognitive test performance in adolescence varies considerably by age. In general, there was a disorganized profile of brain-behavior relationships in adolescence that strengthened with time. That is, there were few strong associations between lGI and cognitive abilities in the youngest participants, but these associations strengthened by mid-adolescence. This was one of several plausible profiles we expected given the well-described relationships between linear adolescent gyrification decreases and cognitive gains that typically plateau before age 18. Unexpectedly, however, the strongest link between local gyrification and cognitive test performance were constrained to mid-adolescence, due to neurobiological mechanisms that remain to be identified in future research. One possibility is that increased estradiol for girls and testosterone for boys may have modulatory effects on age-related changes in the frontoparietal cortex lGI in current study. Although the timing of puberty varies among individuals, it is assumed that the current time window of 15–17 years old for mid-adolescence subgroup in current study occurs after pubertal onset, marked by reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis when dramatic increases in estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone occur (Marceau et al., 2015; Trotman et al., 2013). Research shows that adolescence is a sensitive period of potential increased neuroplasticity (Piekarski et al., 2017) for gonad steroid influence on brain and behavioral development (Schulz and Sisk, 2016), as sex hormones have both organizational and functional effects on the prefrontal, parietal, and temporal cortex in adolescence (Peper et al., 2009; Peper et al., 2011a; Peper et al., 2011b), and also are linked to adolescent mental health (Marceau et al., 2015; Trotman et al., 2013). Future research might attempt to link adolescent gyrification changes directly to sex hormone levels.

Although mediation data analyses show gyrification changes exerting a causal influence on cognitive development, statistical methods are limited to establishing that there is a directed relationship between specific brain regions’ gyrification and specific cognitive abilities. Further experimentation will be needed to identify the mechanistic, neurobiological nature of these relationships. Moreover, we cannot completely exclude a possibility that the causal influences we found might be a direct consequence of other structural changes we did not measure or include in our modeling. Further study ultimately might learn that gyrification might be only indirectly linked to cognitive gains, especially considering that lGI is typically associated with other cortical indices such as surface area and cortical thickness (Forde et al., 2017). The normative reduction in gyrification is but one of several neuroanatomical changes that occur throughout adolescence. There also are reductions in both grey matter volume and cortical thickness with the most reliably large decreases in prefrontal cortex (Giedd et al., 1999; Gogtay et al., 2004; Jernigan et al., 1991; Sowell et al., 2003; Sowell et al., 1999; White and Hilgetag, 2008), as well as and white matter volume and myelination increases (Barnea-Goraly et al., 2005; Schmithorst and Yuan, 2010) (see Juraska and Willing (2016) and Schulz and Sisk (2016) for recent reviews). It might be informative to conduct a multi-modal study with the goal of isolating various types of specific brain structure or function change in adolescence that predict a specific cognitive gain reflect unique influences, then seeking to learn if they are independent factors, or all facets of a single, latent influence that might ultimately be linked to a specific physiological process. In particular, substantial evidence links many of these changes back to either reductions in synaptic density (Huttenlocher, 1979; Huttenlocher and Dabholkar, 1997; Huttenlocher and de Courten, 1987) or the strengthening of long-distance white matter pathways through greater myelination (Juraska and Willing, 2016; Willing and Juraska, 2015) in ways that affect the brain’s overall functional integration. Theories of the mechanisms underlying cortical gyrification also implicate network connectivity (Van Essen, 1997; White and Hilgetag, 2008), suggesting that cortical folding arises, at least in part, to afford advantages to the large-scale wiring of the brain to maximize the greater cortex available in higher primates. This offers the possibility that frontoparietal gyrification decreases in adolescence are one of several brain structure changes that reflect more efficient, firmly established, and mature distributed neural networks. This idea is largely speculative at this point, because only a few clinical studies have directly examined the relationships between local gyrification covariance and structural connectivity as measured by functional neuroimaging (Bos et al., 2015; Schaer et al., 2013). For example, reduced left prefrontal gyrification in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ages 8–18 years) was related to reduced inter-hemispheric structural connectivity (Bos et al., 2015). Future studies should directly examine the relationship between cortical folding and functional connectivity developmental changes in adolescence.

In contrast to the complex gyrification-cognition differences we observed, there was clear, focused evidence for a causal impact of gyrification change on motor inhibition as measured by the number of Commission errors made on the CPT-II assessment. Originally, we focused on frontoparietal brain regions because they are linked to executive and other higher-order cognitive abilities by several lines of research. Frontoparietal brain regions form a core neural system involved in cognitive control across many different types of tasks (Cole et al., 2015; Cole et al., 2012). Frontoparietal brain activation (Barbey et al., 2012; Woolgar et al., 2010), distributed network functional connectivity (Cole et al., 2015; Hearne et al., 2016), and structural connectivity along white matter tracts between frontal and parietal lobe regions (e.g., arcuate fasciulus (Jung and Haier, 2007) consistently have been linked to individual differences in intellectual ability and ‘g’-like estimates of global cognitive ability. Motor response inhibition is an important component of cognitive control and is associated with a broad network of brain activation across different response inhibition tasks (Aron, 2011; Aron et al., 2007; Aron et al., 2004; Baumeister et al., 2014; Durston et al., 2002; Rubia et al., 2003; Swick et al., 2008). Indeed, the extent of frontoparietal gyrification associated with the CPT-II commission errors in the current study is generally consistent with the results of prior neuroimaging studies. For example, the precentral gyrus, the rostral middle frontal gyrus (BA10), the bilateral inferior parietal cortex and supramarginal cortex are among the brain regions commonly reported during performance of CPT tasks or similar paradigms involving motor control (Adler et al., 2001; Bartes-Serrallonga et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2013; Ogg et al., 2008; Sepede et al., 2012). Our results are generally consistent with proposals that optimal inhibitory control requires efficient cognitive processing and integration of numerous cognitive processes (Luna et al., 2015; Luna et al., 2010). Motor inhibition not only requires clear visual discrimination, but also the ability to consistently maintain goal representation, protect task-relevant information within a continually updated working memory store by filtering out task-irrelevant information, sustained attention, and selecting among competing motor plans. One possible reason for the specificity of causal influence of gyrification only on CPT Commissions is that the other tests we examined required less multi-process integration. The best way to assess this would be to re-examine the relationship of gyrification to cognitive development using an even larger test battery than we used, assessing various, non-executive domains like social, emotional, and reward-based processing in addition to aspects of attention, cognitive control, and intellectual ability. Perhaps an expanded battery of tests might find additional causal effects.

A secondary aim of this study was to explore sex-specific patterns of gyrification associated with cognitive ability. We found sexual dimorphism in terms of gyrification patterns associated with verbal intelligence in left lateral orbitofrontal and right postcentral gyrus, while female adolescents showed positive associations in those regions. Importantly, such sexual dimorphism appears to occur around mid-adolescence (ages 15–17). A greater degree of gyrification in females might be related to the factors that yield generally smaller subcortical and insular cortex volumes in females compared to males (see Ruigrok et al. (2014) for a meta-analytic review). This also might reflect the complex effects of sex steroid hormones on brain maturation and development considering that the lateral orbitofrontal cortex has dense estrogen receptors (Genazzani et al., 2007) as reviewed by Peper et al. (2011b) and both boys (n = 125; mean age:17.46 ± 3.27) and girls (n = 115; mean age: 17.30± 3.42) are in the middle of adolescence characterized by a relative surge of testosterone and estradiol hormones (Cameron, 2004; Vigil et al., 2016). We also secondarily examined linear associations between performance on tests of verbal and nonverbal reasoning. These results were somewhat similar to Gregory et al.’s examination of a ‘g’ estimate (Gregory et al., 2016) in that both studies found evidence that left superior frontal and right fusiform gyri covaried with intelligence. However, our findings were less pronounced, and limited to verbal intelligence after correcting for multiple comparisons. The difference might be in the somewhat smaller sample size, but more likely reflect our use of specific test scores rather than broad composite ones. Although Gregory et al. concluded that both adolescent and adult samples showed comparable associations between lGI and ‘g’, a close look at their supplemental material reveals nearly as many regional differences as similarities. Our study expands upon the differences by statistically verifying that gyrification changes with age both within and outside frontoparietal regions.

The study has several noteworthy strengths and limitations. First, the large sample size and use of a whole brain statistical control for multiple comparisons inspire confidence in the reported results here. It also is of note the small differences across age × cognitive performance effect maps implicate regions that are consistent with the prior studies showing regional functional specialization. For example, CPT-II variability in current study was related to age-related lGI changes in motor-specialized brain regions including paracentral and precentral gyri (BA6). CPT-II Omission errors were linked to age-related lGI changes in brain regions that overlap with the dorsal frontoparietal attention network (Luo et al., 2010). Study limitations include the fact that our a priori hypothesis was descriptive, i.e., our goal was to determine if development changed gyrification-cognition relationships in a way that would prompt future study of what neural mechanisms might drive such changes. As such, the study cannot speak directly in support of any of the multiple mechanistic models proposed to drive cortical folding or unfolding (Fernandez et al., 2016b; Ronan and Fletcher, 2015). Despite this, the fact that local gyrification changes contributed to age-related cognitive development in only one functional context would argue against the idea that the same factors that prompt folding in utero can explain adolescent gyrification reductions. In other words, the genetic factors (Fernandez et al., 2016a; Zilles et al., 2013), cellular processes (Striedter et al., 2015), or molecular regulation (Sun and Hevner, 2014) of physiological changes that are known to be important to early brain development when building a folded cortical mantle are unlikely to have a direct a role in the lGI changes that influence a single cognitive ability, or otherwise the relationship would be more widespread. Our evidence suggests gyrification influences are cognitively specific, so a larger and more diverse test battery would be advantageous in future studies to fully chart any differences in lGI-cognition associations. Another limitation to developmental inferences is the study’s cross-sectional design. Although it is useful to obtain an initial snapshot of maturation-related differences, it ultimately will be more effective to capture developmental changes using a longitudinal study design. Finally, there are other not-fully understood factors related to registration process such as motion-related artifacts that might have affected cluster inference (Fischl et al., 1999; Reuter et al., 2010). It is necessary to examine what and how such methodological flaws may mislead cluster interference in future studies.

In sum, the current study goes beyond prior findings that suggest cortical gyrification could be relevant to general cognitive ability in healthy adulthood by providing evidence that suggests frontoparietal gyrification changes have functional significance for cognitive development. Not only do lGI brain-cognition relationships shift over adolescence, frontoparietal changes are instrumental in contributing to the maturation of motor response inhibition ability. Abnormal local cortical gyrification has been proposed as a possible endophenotype for numerous neuropsychiatric disorders (Fan et al., 2013; Hyatt et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016; White and Gottesman, 2012; Yang et al., 2016) that arise in childhood and adolescence (Paus et al., 2008). Thus, it is of obvious interest to chart the normative trajectory of such associations, determine if particular regional gyrification patterns are cognitively specific, and seek evidence for what specific physiological processes might underlie the normative reductions in lGI that have been observed across multiple studies. Considering the majority of psychopathology including schizophrenia and mood disorder tends to emerge during adolescence and its clinical presentations differ between females and males (Paus et al., 2008), this line of work may help characterize the neural basis of normal brain development, which can be ultimately applied to detect early symptoms of psychopathology at adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health, R01MH080956 and R01MH081969.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler CM, Sax KW, Holland SK, Schmithorst V, Rosenberg L, Strakowski SM. Changes in neuronal activation with increasing attention demand in healthy volunteers: an fMRI study. Synapse. 2001;42:266–272. doi: 10.1002/syn.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman-Gomez Y, Janssen J, Schnack H, Balaban E, Pina-Camacho L, Alfaro-Almagro F, Castro-Fornieles J, Otero S, Baeza I, Moreno D, Bargallo N, Parellada M, Arango C, Desco M. The human cerebral cortex flattens during adolescence. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15004–15010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1459-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR. From reactive to proactive and selective control: developing a richer model for stopping inappropriate responses. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Durston S, Eagle DM, Logan GD, Stinear CM, Stuphorn V. Converging evidence for a fronto-basal-ganglia network for inhibitory control of action and cognition. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11860–11864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3644-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbey AK, Colom R, Solomon J, Krueger F, Forbes C, Grafman J. An integrative architecture for general intelligence and executive function revealed by lesion mapping. Brain. 2012;135:1154–1164. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Yarkoni T. Introduction to the special issue on reliability and replication in cognitive and affective neuroscience research. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2013;13:687–689. doi: 10.3758/s13415-013-0201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea-Goraly N, Menon V, Eckert M, Tamm L, Bammer R, Karchemskiy A, Dant CC, Reiss AL. White matter development during childhood and adolescence: a cross-sectional diffusion tensor imaging study. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1848–1854. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartes-Serrallonga M, Adan A, Sole-Casals J, Caldu X, Falcon C, Perez-Pamies M, Bargallo N, Serra-Grabulosa JM. Cerebral networks of sustained attention and working memory: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study based on the Continuous Performance Test. Rev Neurol. 2014;58:289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister S, Hohmann S, Wolf I, Plichta MM, Rechtsteiner S, Zangl M, Ruf M, Holz N, Boecker R, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Holtmann M, Laucht M, Banaschewski T, Brandeis D. Sequential inhibitory control processes assessed through simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Neuroimage. 2014;94:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly PV, Taber LA, Kroenke CD. Mechanical forces in cerebral cortical folding: A review of measurements and models. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2014;29:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JR, Miller PH. A Developmental Perspective on Executive Function. Child Development. 2010;81:1641–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01499.x. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Falk CF, Savalei V. Assessing Mediational Models: Testing and Interval Estimation for Indirect Effects. Multivariate Behav Res. 2010;45:661–701. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.498292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos DJ, Merchan-Naranjo J, Martinez K, Pina-Camacho L, Balsa I, Boada L, Schnack H, Oranje B, Desco M, Arango C, Parellada M, Durston S, Janssen J. Reduced Gyrification Is Related to Reduced Interhemispheric Connectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver TS. The variable nature of cognitive control: a dual mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, Fotenos AF, Marcus D, Morris JC, Snyder AZ. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage. 2004;23:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse M, Whiteside D. Detecting suboptimal cognitive effort: classification accuracy of the Conner’s Continuous Performance Test-II, Brief Test Of Attention, and Trail Making Test. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26:675–687. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.679623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JL. Interrelationships between hormones, behavior, and affect during adolescence: understanding hormonal, physical, and brain changes occurring in association with pubertal activation of the reproductive axis. Introduction to part III. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:110–123. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M, Ito T, Braver T. Lateral prefrontal cortex contributes to fluid intelligence via multi-network connectivity. Brain Connect. 2015;5:497–504. doi: 10.1089/brain.2015.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Yarkoni T, Repovs G, Anticevic A, Braver TS. Global connectivity of prefrontal cortex predicts cognitive control and intelligence. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8988–8999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0536-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Schneider W. The cognitive control network: Integrated cortical regions with dissociable functions. Neuroimage. 2007;37:343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Corporation P. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Integrated) 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW, Chen G, Glen DR, Reynolds RC, Taylor PA. FMRI Cluestering in AFNI:False Positive Rates Redux. Brain Connectivity. 2017 doi: 10.1089/brain.2016.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauvermann MR, Mukherjee P, Moorhead WT, Stanfield AC, Fusar-Poli P, Lawrie SM, Whalley HC. Relationship between gyrification and functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in subjects at high genetic risk of schizophrenia. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:434–442. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty AR, Hagler DJ, Jr, Panizzon MS, Neale MC, Eyler LT, Fennema-Notestine C, Franz CE, Jak A, Lyons MJ, Rinker DA, Thompson WK, Tsuang MT, Dale AM, Kremen WS. Does degree of gyrification underlie the phenotypic and genetic associations between cortical surface area and cognitive ability? Neuroimage. 2015;106:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durston S, Thomas KM, Worden MS, Yang Y, Casey BJ. The effect of preceding context on inhibition: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2002;16:449–453. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H. Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:7900–7905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602413113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk CF, Biesanz JC. Two cross-platform programs for inferences and interval estimation about indirect effects in mediational models. SAGE Open. 2016:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Palaniyappan L, Tan L, Wang J, Wang X, Li C, Zhang T, Jiang K, Xiao Z, Liddle PF. Surface anatomical profile of the cerebral cortex in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a study of cortical thickness, folding and surface area. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1081–1091. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasmer OB, Mjeldheim K, Forland W, Hansen AL, Syrstad VE, Oedegaard KJ, Berle JO. Linear and non-linear analyses of Conner’s Continuous Performance Test-II discriminate adult patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder from patients with mood and anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:284. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0993-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez V, Llinares-Benadero C, Borrell V. Cerebral cortex expansion and folding: what have we learned? Embo j. 2016;35:1021–1044. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:272–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<272::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde NJ, Ronan L, Zwiers MP, Schweren LJS, Alexander-Bloch AF, Franke B, Faraone SV, Oosterlaan J, Heslenfeld DJ, Hartman CA, Buitelaar JK, Hoekstra PJ. Healthy cortical development through adolescence and early adulthood. Brain Struct Funct. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1424-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Yucel M, Wood S, Stuart GW, Buchanan JA, Proffitt T, Anderson V, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Individual differences in anterior cingulate/paracingulate morphology are related to executive functions in healthy males. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:424–431. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. Frontal lobe and cognitive development. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:373–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1024190429920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam P, Anstey KJ, Wen W, Sachdev PS, Cherbuin N. Cortical gyrification and its relationships with cortical volume, cortical thickness, and cognitive performance in healthy mid-life adults. Behav Brain Res. 2015;287:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genazzani AR, Pluchino N, Luisi S, Luisi M. Estrogen, cognition and female ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:175–187. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, 3rd, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory MD, Kippenhan JS, Dickinson D, Carrasco J, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Regional Variations in Brain Gyrification Are Associated with General Cognitive Ability in Humans. Curr Biol. 2016;26:1301–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Carrozzo R. Epilepsy and genetic malformations of the cerebral cortex. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106:160–173. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Sicca F, Parmeggiani L. Epilepsy and malformations of the cerebral cortex. Epileptic Disord. 2003;5(Suppl 2):S9–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Jovicich J, Salat D, van der Kouwe A, Quinn B, Czanner S, Busa E, Pacheco J, Albert M, Killiany R, Maguire P, Rosas D, Makris N, Dale A, Dickerson B, Fischl B. Reliability of MRI-derived measurements of human cerebral cortical thickness: the effects of field strength, scanner upgrade and manufacturer. Neuroimage. 2006;32:180–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearne LJ, Mattingley JB, Cocchi L. Functional brain networks related to individual differences in human intelligence at rest. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep32328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervey AS, Epstein JN, Curry JF, Tonev S, Eugene Arnold L, Keith Conners C, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Hechtman L. Reaction time distribution analysis of neuropsychological performance in an ADHD sample. Child Neuropsychol. 2006;12:125–140. doi: 10.1080/09297040500499081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Seidman LJ, Rossi S, Ahveninen J. Distinct cortical networks activated by auditory attention and working memory load. Neuroimage. 2013;83:1098–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurks PP, Adam JJ, Hendriksen JG, Vles JS, Feron FJ, Kalff AC, Kroes M, Steyaert J, Crolla IF, van Zeben TM, Jolles J. Controlled visuomotor preparation deficits in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:66–76. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR. Synaptic density in human frontal cortex - developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Res. 1979;163:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, Dabholkar AS. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387:167–178. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971020)387:2<167::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, de Courten C. The development of synapses in striate cortex of man. Hum Neurobiol. 1987;6:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt CJ, Haney-Caron E, Stevens MC. Cortical thickness and folding deficits in conduct-disordered adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Trauner DA, Hesselink JR, Tallal PA. Maturation of human cerebrum observed in vivo during adolescence. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2037–2049. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung RE, Haier RJ. The Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT) of intelligence: converging neuroimaging evidence. Behav Brain Sci. 2007;30:135–154. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X07001185. discussion 154–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraska JM, Willing J. Pubertal onset as a critical transition for neural development and cognition. Brain Res. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Lyu I, Fonov VS, Vachet C, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Piven J, Dager SR, McKinstry RC, Pruett JR, Jr, Evans AC, Collins DL, Botteron KN, Schultz RT, Gerig G, Styner MA. Development of cortical shape in the human brain from 6 to 24months of age via a novel measure of shape complexity. Neuroimage. 2016;135:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Genc E, Sritharan S, Mohr H, Roux F, Han CE, Kaiser M, Singer W, Uhlhaas PJ. Adolescent brain maturation and cortical folding: evidence for reductions in gyrification. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Broome MR, McGuire PK, David AS, Eddy M, Ozawa F, Goff D, West WC, Williams SC, van der Kouwe AJ, Salat DH, Dale AM, Fischl B. Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:878–888. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange RT, Iverson GL, Brickell TA, Staver T, Pancholi S, Bhagwat A, French LM. Clinical utility of the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II to detect poor effort in U.S. military personnel following traumatic brain injury. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0030915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin SB, Sejnowski TJ. Communication in neuronal networks. Science. 2003;301:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.1089662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Wang L, Shi F, Lyall AE, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Shen D. Mapping longitudinal development of local cortical gyrification in infants from birth to 2 years of age. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4228–4238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3976-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Zhang X, Cui Y, Qin W, Tao Y, Li J, Yu C, Jiang T. Polygenic Risk for Schizophrenia Influences Cortical Gyrification in 2 Independent General Populations. Schizophr Bull. 2016 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucke IM, Lin C, Conteh F, Federline A, Sung H, Specht M, Grados MA. Continuous performance test in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders: the role of sustained attention. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:479–489. doi: 10.1017/S1092852914000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luders E, Narr KL, Bilder RM, Szeszko PR, Gurbani MN, Hamilton L, Toga AW, Gaser C. Mapping the relationship between cortical convolution and intelligence: effects of gender. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2019–2026. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoshe A, Hokken-Koelega AC, van der Lugt A, White T. Reduced cortical complexity in children with Prader-Willi Syndrome and its association with cognitive impairment and developmental delay. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Marek S, Larsen B, Tervo-Clemmens B, Chahal R. An Integrative Model of the Maturation of Cognitive Control. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:151–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Padmanabhan A, O’Hearn K. What has fMRI told us about the development of cognitive control through adolescence? Brain Cogn. 2010;72:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Rodriguez E, Jerbi K, Lachaux JP, Martinerie J, Corbetta M, Shulman GL, Piomelli D, Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB, Joels M, de Kloet ER, Holsboer F, Amodio DM, Frith CD, Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Craig AD. Ten years of Nature Reviews Neuroscience: insights from the highly cited. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:718–726. doi: 10.1038/nrn2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, Essex MJ, Susman EJ. Developmental and Contextual Considerations for Adrenal and Gonadal Hormone Functioning During Adolescence: Implications for Adolescent Mental Health. Dev Psychobiol. 2015;57:742–768. doi: 10.1002/dev.21214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murty VP, Calabro F, Luna B. The role of experience in adolescent cognitive development: Integration of executive, memory, and mesolimbic systems. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;70:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]