Abstract

Background:

The guidelines for digital ulcers (DUs) management in systemic sclerosis (SSc) indicate the use of iloprost to induce wound healing and bosentan to prevent the onset of new DU. The aim of our study was to evaluate whether the combination treatment may surmount the effect of the single drug.

Methods:

We analyzed data regarding 34 patients with SSc and at least one active DU persisting despite 6 months of iloprost therapy, and treated for other 6 months with a combination therapy, i.e. iloprost plus bosentan.

Results:

Overall, patients initially presented 69 DUs (58 on the fingers and 11 on the legs). At the end of the study 34 (49.3%) DUs were completely healed (responding, R), 18 (26.1%) started the healing process (partially responding, PR), and 17 (24.6%) did not respond (NR) to therapy. No new DU was recorded and the ulcers localized on the legs did not respond to the combination therapy. Finally, data have been analyzed by dividing the patients in two groups according to the fibrosis level on the finger. In the group with mild fibrosis, 83.4% of DUs resulted with showing complete healing while, in the group with severe fibrosis, only 18% of DUs were healed (P = 0.024).

Conclusion:

The treatment with iloprost plus bosentan is effective in determining healing of DUs in SSc patients with mild digital skin fibrosis. Conversely, the severity of skin fibrosis strongly influences the healing process of DUs. The study confirmed the efficacy of bosentan to prevent onset of new DUs.

Keywords: Scleroderma, digital ulcer, iloprost, bosentan

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystemic autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by microvascular damage and excessive cutaneous and visceral fibrosis, with an estimated prevalence of 30–120 cases per million.1,2 Vascular injury leads to structural changes, loss of capillaries, and remodeling of the vessel wall resulting in progressive luminal narrowing and eventually vascular occlusion. This process is mediated by molecules that regulate mainly cell apoptosis, proliferation and vasoconstriction including reduction of prostacyclin release, decreased production of nitric oxide (NO), and increased production of endothelin-1 (ET-1).3

ET-1 is a 21-amino acid polypeptide and its signaling is mediated by two transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors (ETA and ETB) with different binding affinity and physiologic effects.4,5 ETA receptors are expressed on vascular smooth muscle cells and primarily mediate vasoconstriction, whereas ETB receptors are expressed both on endothelial cells, mediating vasodilatation, and on smooth muscle cells, mediating vasoconstriction.6 In the serum of patients affected by SSc the levels of ET-1 are increased regarding healthy control participants.7,8

ET-1 may be involved in the structural changes observed in SSc. ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor and may play a role in the development of dermal fibrosis in SSc through its stimulation of matrix biosynthesis by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells.9–11

The clinical manifestations related to vascular involvement in SSc are represented by the Raynaud’s phenomenon and onset of digital ulcers.12 Digital ulcers are defined as denuded areas with well demarcated borders, involving, in different degrees, the epidermis, the dermis, the subcutaneous tissue, and sometimes also the bone, located on the volar surface of the fingers, distal to the proximal interphalangeal joints.13 Digital ulcers occur in 30–58% of patients, and are more frequent in patients with diffuse SSc. Digital ulcers are painful and determine a functional impairment with a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life. Furthermore, chronic ulcers can become infected, leading to gangrene and need of amputation. The healing is slow due to the atrophic, fibrotic, and avascular nature of the local tissue.14

Currently, there is no official algorithm for diagnosis and therapy of digital ischemia leading to digital ulcers in SSc. A conventional therapeutic approach to digital lesions should include vasoactive medications, antiplatelet agents, antibiotics as needed, and analgesia. The response to vasodilators in patients with SSc is variable and often disappointing. There is a visible need for strategies to facilitate healing of the digital ulcers and to prevent occurrence of new lesions.15

The EULAR recommendations16 for the treatment of SSc indicate that the intravenous administration of prostanoids (iloprost) is efficacious in digital ulcers healing, while bosentan, a dual endothelin receptor antagonist with affinity for ETA and ETB receptors, has no confirmed efficacy in the treatment of active digital ulcers in SSc patients. Bosentan has also been demonstrated to be effective at preventing digital ulcers in two multicenter randomized prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies that were conducted in Europe, Canada, and USA, the randomized placebo-controlled investigation of digital ulcers in scleroderma (RAPIDS) -1 and -213,17, and in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon.18,19 Anyway, several case reports suggest that bosentan may be effective also in the treatment of digital ulcers.20,21

Skin thickness is caused by increased collagen and intercellular matrix formation in the dermis, as well as by edema probably caused by both microvascular injury and inflammation. Because of the accumulation of collagen and fluid, the skin becomes thickened, making it impossible to pinch it into a normal skin fold. This first phase is followed by the indurative phase. Besides skin thickening, the skin also becomes shiny, taut, and adherent to the sub cutis. Finally, in the end stage, the skin becomes thin, atrophic, and often tightly tethered to the underlying tissue.22

At present, the most important validated method for measuring the dermal skin thickness is the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS).23

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of a combination treatment with iloprost and bosentan on healing of digital ulcers resistant to therapy only with iloprost, and we addressed this issue evaluating the response of digital ulcers to combination therapy in two groups of SSc patients with different grade of digital skin fibrosis.

Patients and methods

The study is a retrospective analysis of data regarding patients who came to our attention during October 2009 to December 2012. The study has been approved by the local Scientific and Ethical Committee and all patients provided their informed written consent for participation in the study. We analyzed data regarding 34 patients affected by SSc, diagnosed according to Le Roy criteria24 and attending the Rheumatology Unit of IRCCS Scientific Institute and Regional General Hospital “Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza”, San Giovanni Rotondo (FG), Italy. The patients showed at least one active digital ulcer, defined as painful area of at least 2 mm in diameter with visible depth and loss of dermis. The study population was clustered in two groups according to the presence of mild or severe skin digital fibrosis assessed by MRSS method. All patients had been previously treated with iloprost for at least 6 months. Each patient was evaluated for disease duration, subset, precisely diffuse SSc (dSSc) and limited SSc (lSSc), and clinical features (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Total | RSS 1 | RSS 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 43.8 ± 5.9 | 43.1 ± 6.1 | 45.4 ± 5.4 |

| Gender (male/female) | 3/31 | 2/21 | 1/10 |

| Caucasian (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Disease duration (years) (mean ± SD) | 8.9 ± 4.2 | 8.7 ± 4.5 | 9.2 ± 3.6 |

| Diffuse systemic sclerosis (n) (%) | 12 (35.3) | 6 (28.5) | 5 (45.4) |

| Limited systemic sclerosis (n) (%) | 22 (64.7) | 17 (73.9) | 6 (54.5) |

| Number of digital ulcers (mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 2 ± 1 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon (n) (%) | 34 (100) | 23 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Scleroderma renal crisis (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interstitial lung disease (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (n) (%) | 18 (52.9) | 11 (47.8) | 7 (63.6) |

Mild digital skin fibrosis (RSS1) and severe digital skin fibrosis (RSS3) according to the modified Rodnan skin score (MRSS).

Personal medical history for all participants was obtained, including age, gender, diseases, drug use, drug abuse and addiction, smoking and alcohol consumption, physical exercise, and other therapies, i.e. calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and anti-platelet agents. The therapeutic regimen must have remained constant for the period considered. Patients were excluded if they had previously received bosentan. Other exclusion criteria included arterial hypertension, infectious diseases, cancer, thoracic trauma, surgical procedures in the last 180 days, smoke, alcohol or drug addiction, hypo- or hyperthyroidism, psychiatric disorders, anemia by any cause, liver, kidney, or heart failure or condition of being chronically ill, and treatment with chemotherapic or hormonal agents. All patients received bosentan 62.5 mg twice daily for 4 weeks and then 125 mg twice daily and iloprost 0.5–2 ng/kg/min for the duration of 6 h every 4 weeks for 6 months. Blood chemistry, including liver function and total blood count, was monitored every 2 weeks during the first month and every 4 weeks thereafter. At each visit, changes in digital ulcer characteristics were assessed, comparing the number, size, extent, and granulation, recording onset of new digital ulcers and scoring the intensity of pain reported by patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram (DUs, digital ulcers; RSS, severity of skin fibrosis scored by modified Rodnan skin score).

Statistical analysis

Baseline patients’ characteristics were reported as relative frequency (percentage) or mean and standard deviation (SD), for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Comparisons were performed with Wilcoxon signed rank test.25 The discriminatory power of digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS) was assessed by estimating the area (AUC) under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The optimal cutoff was assessed by maximizing jointly sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity, computed at the optimal cutoff, were reported along with their 95% CI. The significance level was set at P <0.05. All analyses were performed and graphs were created using Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The description of demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of the study population is represented in Table 1. The mean age of the 34 enrolled subjects (31 women, 3 men) was 43.8±5.9 years, with a female:male ratio approximately of 10:1. They initially had 69 persistent ulcers: 58 digital ulcers were localized on the fingers and 11 non digital ulcers on the legs, not responsive after 6 months of treatment with iloprost alone. After 6 months of treatment with iloprost plus bosentan 34 ulcers responded (R) (49.3%) and were healed, 18 (26.1%) were in remission (PR), and 17 (24.6%) did not respond (NR) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of total digital ulcers showing evolution after 6 months of combination treatment with iloprost and bosentan.

When we considered only the digital ulcers on the hands, 34 digital ulcers healed (58.6%), while 15 presented a partial remission (25.9%) and only nine digital ulcers did not respond to treatment (15.5%) (Figure 3). The mean of digital ulcers for patient decreased from 1.7 to 0.7 (P = 0.00003).

Figure 3.

Percent of digital ulcers located at the level of the hands showing evolution after 6 months of combination treatment with iloprost and bosentan.

Then we clustered the population in two groups according to digital MRSS: the first group (23 patients) had mild digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS 1) and the second group (11 patients) had severe digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS 3).

The patients with mild skin digital fibrosis (finger-RSS 1) initially had 36 digital ulcers, and after 6 months of treatment with bosentan and iloprost 30 digital ulcers healed (83.4%) and six presented partial remission (16.6%).

The 11 patients with severe skin digital fibrosis (finger-RSS 3) had initially 22 digital ulcers and after 6 months of treatment with bosentan and iloprost only four had complete recovery (18%), nine were in partial remission (41%), and nine did not respond (41%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response rate of digital ulcers to bosentan in relationship to the severity of skin fibrosis.

| Responding (R) | Partially responding (PR) | Not responding (NR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSS 1 | 83.4% | 16.6% | 0 |

| RSS 3 | 18% | 41% | 41% |

| P = 0.024 | P = 0.0004 | P = 0.0001 |

RSS 1, mild digital skin fibrosis; RSS 3, severe digital skin fibrosis.

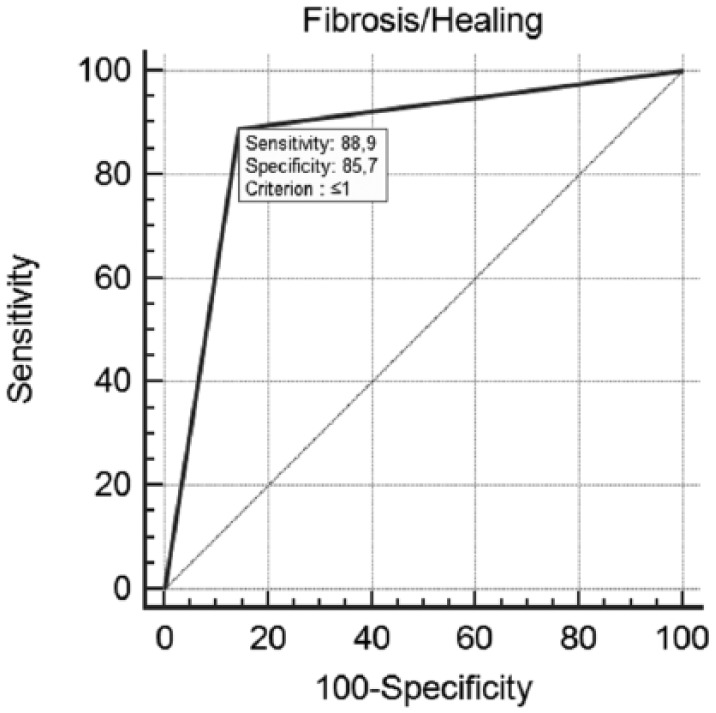

By comparing the results observed in the groups with mild and severe digital skin fibrosis, respectively, R digital ulcers were 83.4% vs. 18% (P = 0.024), PR digital ulcers were 16.6% vs. 41% (P = 0.0004), NR digital ulcers were 0% vs. 41% (P = 0.0001) (Figure 4). The ROC curve shows that the value of digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS) ⩽1 is favorable to healing, with a sensivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 85.7% (Figure 5). In our study population the therapy with iloprost and bosentan in combination was not effective in healing non-digital ulcers on lower limbs: after 6 months of treatment, none of the 11 ulcers healed and only four showed partial regression. Besides, during the treatment we did not observe the development of new digital ulcers, and bosentan therapy in our patients was well tolerated and no adverse event was recorded. In the observation period there was complete adherence to the therapeutic protocol and no treatment discontinuation.

Figure 4.

Digital ulcers healing and severity of skin fibrosis scored by modified Rodnan skin score (RSS).

Figure 5.

ROC curve for digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS). Receiver-operating characteristic analysis curve shows an optimal cutoff value of digital skin fibrosis (finger-RSS) ⩽1 for detecting the propensity to healing with a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 85.7%.

Discussion

Digital ulcers are a major clinical problem in patients affected by SSc, considering that they are very painful, lead to a great deal of disability, and the healing is slow due to the atrophic, fibrotic, and avascular nature of the local tissue. Digital ulcers are related to recurrent ischemia from various processes, including vasospasm from Raynaud’s phenomenon, thrombosis of digital arteries, calcinosis, and structural microvascular changes related to the underlying SSc. Recurrent trauma, particularly in patients with joint contractures, also contributes to the development of digital ulcers in patients with SSc.26 The management of digital ulcers in patients affected by SSc is complex and multifaceted, and includes: (1) non-pharmacologic therapies, such as avoidance of triggers of Raynaud’s phenomenon, avoidance of trauma and use of occlusive and topical hydrocolloid dressings; (2) pharmacologic therapies, such as supportive measures (pain medications and antibiotics), vasodilating agents (calcium channel blockers, nitrates, iloprost, bosentan, sildenafil), anti-platelet therapies (aspirin, dipyridamole), anticoagulant therapies (heparin, pentoxifylline); (3) surgical therapies.27 The EULAR/EUSTAR recommendations for the treatment of SSc indicate that only intravenous prostanoids, in particular iloprost, should be considered in the treatment of active digital ulcers, while bosentan is considered ineffective in the treatment of digital ulcers.16 Anyway, Khun et al. in 2010 demonstrated that bosentan increased the number of healed digital ulcers from 42% at baseline to 88% at the 24th week [28]. Furthermore, a Spanish study conducted in 2008 concluded that bosentan may be a safe long-term alternative for treating and preventing the recurrence of skin ulcers and healed ulcers in SSc patients.29 In another recent study, the effects of bosentan treatment on the number of healed digital ulcers and on the number of new skin ulcers were evaluated in 26 patients with SSc over a period of 36 months. A significant reduction in the mean number of digital ulcers per patient could be found, as well as healing of skin ulcers in 65% of patients after a median of 25 weeks of bosentan treatment.30 Hence, these data suggest that bosentan may be beneficial not only in the prevention of new ulcers, but also in the healing process. Based on these premises, we decided to try to validate previous results and, for the first time, we decided to evaluate the effects of the treatment in patients with different degrees of digital fibrosis. Importantly, we have shown that bosentan associated to iloprost is effective in the healing of ulcers in scleroderma patients refractory to previous treatments and characterized by mild digital fibrosis, whereas it is ineffective in patients with severe digital fibrosis. Approximately 50% of digital ulcers were healed after 6 months of treatment with iloprost and bosentan and in 25% of the lesions partial remission was observed. When we clustered the patients according to the grade of digital fibrosis scored by finger-RSS value, in the group of SSc patients characterized by mild digital skin fibrosis digital ulcers healing was recorded in approximately 80% of the lesions and partial regression in approximately 16% of the lesions after 6 months of treatment with bosentan and iloprost, whereas in the group of SSc patients characterized by severe digital skin fibrosis digital ulcers healing was recorded in 18% of the lesions and partial remission in 41% of the lesions. Fibrosis might be considered as the most prominent hallmark of SSc, its occurrence is not restricted to the skin, but can involve lung, heart, and gastrointestinal tract. The pathophysiological alterations underlying fibrotic responses in SSc are characterized by prolonged and exaggerated activation of fibroblasts and maintenance of fibroblast-mediated effects. The transdifferentiation of fibroblasts in myofibrobasts, able to synthesize collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix, as well as TGF-β, plays a pivotal role in fibrosis. In contrast with physiological wound healing, where myofibroblasts only occur transiently within the granulation tissue, their persistence in SSc patients, leading to contracture of extracellular matrix with chronic scarring and delaying ulcers healing.31 ET-1 exerts a pro-fibrotic effect on normal dermal fibroblasts by activating the c-Abl/PKC-δ/Fli1 pathway, and bosentan reverses the pro-fibrotic phenotype of SSc dermal fibroblasts and prevents the development of dermal fibrosis in bleomycin-treated mice by blocking this signaling pathway.32 But in our patients we did not observe improvement of skin fibrosis after treatment with bosentan. Non-digital ulcers on lower extremity are less prevalent. In a recent clinical study the prevalence in scleroderma patients was estimated at 4%, anyway they represent a challenging and underestimated complication of the disease causing important pain and morbidity.33 The etiology of these ulcers is unknown; it is thought that micro traumas and venous insufficiency play an important role, and in a study conducted on a small number of patients a higher than expected frequency of antiphospholipid antibodies and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) mutation were identified in SSc patients with lower extremity ulcers.27 Two recent case reports described the healing of a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with longstanding SSc after 6 months of therapy with bosentan.33–35 In our study, eight patients also had non-digital ulcers on the lower limbs, for a total of 11 ulcers, but after 6 months of treatment with iloprost and bosentan, no ulcer was healed and only four showed a partial remission. Besides, we confirmed that bosentan is effective at preventing onset of digital ulcers in patients affected by scleroderma, considering that no new digital ulcer occurred in our SSc patients during and after the 6 months of therapy. The limits of the present study are the small number of patients and the lack of a control group. As we said before, this is a retrospective observational study carried out in a single center and systemic sclerosis remains a rare disease. About the control group, this study represents a real-life approach and all the patients were treated as indicated in the recent EULAR/EUSTAR guidelines.

Our study showed that the treatment with bosentan in combination with iloprost is effective in determining the healing of digital ulcers in SSc patients refractory to previous treatments, but is ineffective for the treatment of ulcers located on the lower extremity. The concurrent therapy with bosentan and iloprost is effective particularly in patients with mild skin digital fibrosis, while in patients with severe fibrosis the combination therapy has been shown to be markedly less effective, suggesting that skin fibrosis is the main feature of scleroderma which is opposed to the healing of digital ulcers.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the “5×1000” voluntary contribution and by a grant (GM) from the Italian Ministry of Health (RC1201ME04, RC1203ME46, RC1302ME31, and RC1403ME50) through Department of Medical Sciences, Division of Internal Medicine, IRCCS Scientific Institute and Regional General Hospital “Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza”, Opera di Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, San Giovanni Rotondo (FG), Italy.

References

- 1. Hunzelmann N, Genth E, Krieg T, et al. (2008) The registry of the German Network for Systemic Scleroderma: Frequency of disease subsets and patterns of organ involvement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 1185–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C, et al. (2008) Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: A systematic literature review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 37: 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katsumoto TR, Whitfield ML, Connolly MK. (2011) The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Annual Review of Pathology 6: 509–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frommer KW, Müller-Ladner U. (2008) Expression and function of ETA and ETB receptors in SSc. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47 (Suppl. 5): v27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clozel M, Fischli W, Guilly C. (1989) Specific binding of endothelin on human vascular smooth muscle cells in culture. Journal of Clinical Investigation 83: 1758–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jain M, Varga J. (2006) Bosentan for the treatment of systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis and digital ulcers. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 7: 1487–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biondi ML, Marasini B, Bassani C, et al. (1991) Increased plasma endothelin levels in patients with Raynuad’s phenomenon. New England Journal of Medicine 324: 1139–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamane K, Miyauchi T, Suzuki N, et al. (1992) Significance of plasma endothelin-1 levels in patients with systemic sclerosis. Journal of Rheumatology 19: 1566–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kahaleh MB. (1991) Endothelin, an endothelial dependent vasoconstrictor in scleroderma: Enhanced production and profibrotic action. Arthritis and Rheumatism 34: 978–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu S, Denton CP, Holmes A, et al. (1998) Endothelins: Effect on matrix biosynthesis and proliferation in normal and scleroderma fibroblast. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 31 Suppl 1: S360–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vancheeswaran R, Magoulas T, Efrat G, et al. (1994) Circulating endothelin-1 levels in systemic sclerosis subsets–a marker of fibrosis or vascular dysfunction? Journal of Rheumatology 21: 1838–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galluccio F, Matucci-Cerinic M. (2011) Two faces of the same coin: Raynaud phenomenon and digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity Reviews 10: 241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. (2004) Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis and Rheumatism 50: 3985–3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vitiello M, Abuchar A, Santana N, et al. (2012) An update on the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis: The dermatologist’s point of view. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology 5: 33–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schiopu E, Impens AJ, Phillips K. (2010) Digital ischemia in scleroderma spectrum of diseases. International Journal of Rheumatology 2010. pii: 923743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kowal-Bielecka O, Landewé R, Avouac J, et al. (2009) EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis: A report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 68: 620–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matucci-Cerinic M, Denton CP, Furst DE, et al. (2011) Bosentan treatment of digital ulcers related to systemic sclerosis: Results from the RAPIDS-2 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 70: 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Selenko-Gebauer N, Duschek N, Minimair G, et al. (2006) Successful treatment of patients with severe secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon with the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan. Rheumatology 45 (Suppl. 3): iii45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hettema ME, Zhang D, Bootsma H, et al. (2007) Bosentan therapy for patients with severe Raynaud’s phenomenon in systemic sclerosis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 66: 1398–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chamaillard M, Heliot-Hosten I, Constans J, et al. (2007) Bosentan as a rescue therapy in scleroderma refractory digital ulcers. Archives of Dermatology 143: 125–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snyder MJ, Jacobs MR, Grau RG, et al. (2005) Resolution of severe digital ulceration during a course of bosentan therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine 142: 802–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Czirják L, Foeldvari I, Müller-Ladner U. (2008) Skin involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47 (Suppl. 5): v44–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clements PJ, Meedsger TA, Jr, Feghali CA. (2004) Cutaneous involvement in systemic sclerosis. In: Clements PJ, Furst DE. editors. Systemic sclerosis. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- 24. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. (1988) Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): Classification, subsets and pathogenesis. Journal of Rheumatology 15: 202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siegel S. (1956) Non-parametric statistic for the behavioral science. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arefiev K, Fiorentino DF, Chung L. (2011) Endothelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. International Journal of Rheumatology 2011: 201787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chung L, Fiorentino D. (2006) Digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity Reviews 5: 125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuhn A, Haust M, Ruland V, et al. (2010) Effect of bosentan on skin fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: A prospective, open-label, non-comparative trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49: 1336–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. García de, la Peña-Lefebvre P, Rodríguez Rubio S, Valero Expósito M, et al. (2008) Long-term experience of bosentan for treating ulcers and healed ulcers in systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47: 464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsifetaki N, Botzoris V, Alamanos Y, et al. (2009) Bosentan for digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis: A prospective 3-year followup study. Journal of Rheumatology 36: 1550–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Geyer M, Müller-Ladner U. (2011) The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis revisited. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology 40: 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akamata K, Asano Y, Aozasa N, et al. (2014) Bosentan reverses the pro-fibrotic phenotype of systemic sclerosis dermal fibroblasts via increasing DNA binding ability of transcription factor Fli1. Arthritis Research & Therapy 16: R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shanmugam VK, Price P, Attinger CE, et al. (2010) Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: Features and response to therapy. International Journal of Rheumatology 2010: pii: 747946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taniguchi T, Asano Y, Hatano M, et al. (2012) Effects of bosentan on nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. British Journal of Dermatology 166: 417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naert A, De Haes P. (2013) Successful treatment with bosentan of lower extremity ulcers in a scleroderma patient. Case Reports in Medicine 2013: 690591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]