Abstract

Abnormalities in peripheral blood natural killer (NK) cells have been reported in women with primary infertility and recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) and several studies have been presented to define cutoff values for abnormal peripheral blood NK cell levels in this context. Elevated levels of NK cells were observed in infertile/RSA women in the presence of thyroid autoimmunity (TAI), while no studies have been carried out, to date, on NK cells in infertile/RSA women with non-autoimmune thyroid diseases. The contribution of this study is two-fold: (1) the evaluation of peripheral blood NK cell levels in a cohort of infertile/RSA women, in order to confirm related data from the literature; and (2) the assessment of NK cell levels in the presence of both TAI and subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) in order to explore the possibility that the association between NK cells and thyroid function is not only restricted to TAI but also to SCH. In a retrospective study, 259 age-matched women (primary infertility [n = 49], primary RSA [n = 145], and secondary RSA [n = 65]) were evaluated for CD56+CD16+NK cells by flow cytometry. Women were stratified according to thyroid status: TAI, SCH, and without thyroid diseases (ET). Fertile women (n = 45) were used as controls. Infertile/RSA women showed higher mean NK cell levels than controls. The cutoff value determining the abnormal NK cell levels resulted ⩾15% in all the groups of women. Among the infertile/RSA women, SCH resulted the most frequently associated thyroid disorder while no difference resulted in the prevalence of TAI and ET women between patients and controls. A higher prevalence of women with NK cell levels ⩾15% was observed in infertile/RSA women with SCH when compared to TAI/ET women. According to our data, NK cell assessment could be used as a diagnostic tool in women with reproductive failure and we suggest that the possible association between NK cell levels and thyroid function can be described not only in the presence of TAI but also in the presence of non-autoimmune thyroid disorders.

Keywords: autoimmunity, infertility, natural killer cells, recurrent spontaneous abortion, thyroid

Introduction

Infertility concerns the inability to achieve pregnancy after 1 year of unprotected intercourse, while recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) is defined by the occurrence of two or more consecutive failed pregnancies.1 Spontaneous abortions are mostly caused by chromosomal abnormalities in embryos2 and anatomic uterine defects appear to predispose women to reproductive difficulties.3 Mechanisms of unexplained reproductive failure (infertility and RSA) involve immune-mediated pathways including the presence of a predominant T helper (Th)1-type immunity during pregnancy, a decrease in T regulatory cells and an increase in natural killer (NK) cells.4,5 These phenomena can occur locally, at the site of implant, and can be observed also in the peripheral blood.4,5 It has been shown that the interaction between human leucocyte antigen (HLA) molecules and NK cells is the checkpoint of the regulation of the NK cell activity at the maternal–fetal interface.6 NK cells are innate immune effectors that are able to exert a cytolitic activity against infected and tumor cells and to produce immunomodulatory cytokines without HLA restriction or prior sensitization.7–10 Peripheral blood NK cells comprise about 10–12% of blood lymphocytes and are strikingly suppressed in normal early pregnancy. On the other hand, NK cells constitute the predominant leukocyte population present in the endometrium at the time of implantation and in early pregnancy. Decidual NK cells (dNK) are a specific CD16-cell subset that includes selective expression of CD9, galectin-1, and glycodelin, with regulatory effects on T cells. Since peripheral NK cells downregulate dNK under the influence of estrogen and progesteron levels, both the hormonal status and the NK cytokines contribute to the shift towards a Th2 response that characterizes normal pregnancy.11,12 Interactions between immune cells and thyroid function are well-established.13–18 Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors can be found on several cells of the immune system and bone marrow hematopoietic cells, splenic dendritic cells, T cells, and B cells can produce TSH. Studies suggest that thyroid hormones (thyroxine – T4, and triiodothyronine – T3) act on dendritic cells, NK cells, and T cells.13–18 These interactions are assumed to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of certain thyroid diseases, including non-toxic goiter and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid disorders can be associated with infertility/RSA and the morbidity of pregnancies.19–21 It is reported that mild thyroid abnormalities are associated with an increased rate of miscarriage and this poor obstetrical prognosis seems to be related to an impaired thyroid adaptation to pregnancy.22 Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) of the mother may impair the course of pregnancy and may disturb the normal development of the fetus.19–21 Moreover, it has been reported that the presence of thyroid autoimmunity (TAI) leads to an increased risk of infertility and RSA even in the absence of clinically overt hypothyroidism.23–26

Abnormalities in number and activation of NK cells have been related to RSA and several studies aimed at addressing the cutoff values for peripheral blood NK cell levels in this context.27–32 Elevated levels of peripheral blood NK cells were reported in the presence of TAI in women with RSA suggesting an interplay between NK cells and autoimmune thyroid disorders.26,33 No studies have been carried out, to date, on the relationship between non-autoimmune thyroid diseases, such as SCH, and NK cells in women with reproductive failure.

The contribution of this study is two-fold: (1) the evaluation of peripheral blood NK cell levels in a cohort of infertile/RSA women; and (2) the assessment of NK cell levels in the presence of both TAI and SCH, in order to explore the possibility that the association between NK cells and thyroid function is not only restricted to TAI but also to SCH.

Materials and methods

The present study was designed as a retrospective study conducted in a single center: medical records of women who were registered at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics II, San Giovanni-Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy, were reviewed consecutively. Among 1500 consecutive outpatients of the Department, during the period 2008–2011, who were affected by reproductive failure, we excluded from the study all the women that met the following exclusion criteria (82.7%, 1241/1500): anatomical defects (15%), infectious causes (5%), chromosomal abnormalities (3%), male factor of the women’s partners (5%), primary and acquired thrombophilia (22%, including anti-phospholipid syndrome), poor ovarian reserve (8%), or autoimmune/endocrine disorders other than thyroid diseases (24%). Women with a diagnosis of overt hypothyroidism or Graves’ disease as well as women who underwent either voluntary termination of pregnancy or assisted reproductive techniques were also excluded (18%). Laboratory assays included karyotyping of the couple, semen analyses of women’s partners, serum levels of prolactin, estradiol, luteinizing-hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, androgens, thyroid function and autoantibodies, coagulation factors, anti-phospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, IgG and IgM anti-cardiolipin, anti-β2glicoprotein I antibodies, anti-annexin V, and anti-prothrombin antibodies), culture studies for Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma, PCR for Chlamydia, and imaging (pelvic ultrasonography, hysterosalpingography and hysteroscopy, performed as needed).34 Two hundred and fifty-nine age-matched Caucasian women composed the study population and were divided in three groups: primary infertility (n = 49); primary RSA (n = 145); and secondary RSA (n = 65). Primary infertility was defined, according to the Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine,1 as the inability to conceive a child after 12 months of regular sexual intercourse, without contraception, in couples who have never had a child. Women with RSA had a history of two or more consecutive spontaneous abortions prior to the 20° gestational week (GW) and were divided in two groups depending on their parity: primary RSA included women who never had a successful previous pregnancy while secondary RSA included women who achieved at least one previous successful pregnancy. Medical records of 45 women in the age of fertility who were registered at the same hospital were serially reviewed as a comparison group. These fertile controls met the following selection criteria: they experienced successful pregnancies (women with ⩽1 previous spontaneous abortion were also included); they had not a previous history of infertility/RSA and voluntary termination of pregnancy or assisted reproductive techniques; they showed regular ovulatory cycles and normal basic hormone profile; and they did not suffer from acute inflammatory / autoimmune / endocrine disorders other than thyroid diseases (women with a diagnosis of Graves’ disease were excluded) at the time of the medical evaluation. Data of fertile controls were confirmed by medical history, and clinical and laboratory examination. None of the women in the study was pregnant or was on immune-suppressive/modulatory treatment, hormonal therapy (including thyroxine replacement and/or contraceptive pills), or antibiotics at the time of laboratory assays.

Laboratory assays

Women in the study underwent laboratory assays as part of their medical care before conception. Laboratory assays were performed on the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (days 3–5).34 All the women were screened for the presence of anti-thyroglobulin antibody (ATG) and anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO), by using a highly sensitive electrochemiluminescent immunoassay. Thyroid hormones (free thyroxine – FT4, and free triiodothyronine – FT3) and TSH were assessed using the immunoassay system. Normal values were: 2-5 pg/mL for FT3; 8.5–20 pg/mL for FT4. ATG >65 IU/mL and TPO >115 IU/mL were considered positive. SCH was defined as the basal TSH higher than 2.5 mIU/L with normal FT4 and/or impaired TSH response to the short-thyrotrophic-releasing hormone (TRH) test.21,22,34,35 Anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) were evaluated by indirect immunofluorescence using Hep2 cells as substrate. ANA titer ⩾ 1:160 was considered positive. Serum insulin and glucose were measured to assess the HOMA (Homeostasis Model Assessment) index (Insulin [mU/mL] × Glucose [mmol/L]/22.5: values <2.7 were considered negative).21,34 Immuno-phenotypic analysis of peripheral blood NK cells were performed using fresh EDTA-K3 anti-coagulated blood samples from all the women. Immunophenotypic analysis of peripheral blood immune cells were performed with regard to CD45 for the total lymphocyte count, CD16 and CD56 for the NK cells, by fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody staining and flow cytometry analysis. NK cells were identified by positivity of both CD16 and CD56.34 The NK cell count was expressed as a percentage of the total lymphocyte count (NK cell/lymphocyte). All the women included in the study underwent during their medical care physical and ultrasonographic examination of thyroid gland in order to detect undiagnosed non-toxic goiter as focal nodules and/or diffuse or heterogeneous echogenic abnormalities throughout the gland.24,35

This study was approved by the local ethics committee. It was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with the guidelines for good clinical practice.

Statistical analyses

All data were stored on a server and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software Version 6. To test the normality of datasets the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus test was used. Normal variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between mean values were determined by Student’s t-test while the contingency analyses were performed by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. The measure of association was obtained using odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (CI) was reported. The significance of any correlation was determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. For the evaluation of the NK cell assessment as a diagnostic test receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed; accuracy was measured by the area under the ROC curve (AUC). If the AUC value was greater than 0.5, the test was considered as a significant method to detect cellular immune abnormality in the patients.34 We considered the Youden’s index with likelihood ratio (LR) >2 as a criterion for choosing the “optimal” threshold value, the threshold value for which Sensitivity(c) + Specificity(c) -1 is maximized. LR summarizes information regarding sensitivity and specificity; positive LR was calculated as follows: sensitivity divided by (1-specificity). Statistical analysis was considered significant when P values were less than 0.05.

Results

Demografic and infertility data of women in the study population were reported in Table 1. No difference resulted in the age comparing the groups of women and no difference in the number and GW of spontaneous abortions resulted between the primary and secondary RSA women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and infertility data of women in the study population.

| Primary infertility (n = 49) | Primary RSA (n = 145) | Secondary RSA (n = 65) | Controls (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40 ± 3.6 | 37.3 ± 5 | 38 ± 4 | 37 ± 4.6 |

| SA (n) | None | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.5 |

| GW (n) | – | 8.9 ± 3 | 8.9 ± 3.7 | 8 ± 2.8 |

| Living children (n) | None | None | 1 ± 0.3 | 2 ± 1 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

GW: gestational week; RSA: recurrent spontaneous abortion; SA: spontaneous abortion.

Mean values of TSH, FT3, FT4, HOMA index, and the prevalence of ATG/TPO/ANA positive women resulted similar comparing the groups of women enrolled (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basic hormonal and autoimmune data in the study population.

| Primary infertility (n = 49) | Primary RSA (n = 145) | Secondary RSA (n = 65) | Controls (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH mIU/L | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 2 ± 2 | 1.6 ± 0.8 |

| FT3 pg/mL | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1 | 2.9 ± 0.7 |

| FT4 pg/mL | 12 ± 3.4 | 8.7 ± 6 | 8.4 ± 5 | 11 ± 2 |

| ATG positive* (n/%) | 15/30.6 | 29/20 | 17/26.2 | 9/20 |

| TPO positive* (n/%) | 10/20.4 | 20/13.8 | 13/20 | 7/15.6 |

| ANA positive† (n/%) | 0/0 | 12/8.3 | 5/3.4 | 0/0 |

| HOMA | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

ATG and TPO were positive as >65 IU/mL and >115 IU/mL, respectively.

ANA were positive as ⩾ 1:160.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

ANA: anti-nuclear antibodies; ATG: anti-thyroglobulin antibody; FT3: free triiodothyronine; FT4: free thyroxine; HOMA: Homeostasis Model Assessment.

RSA: recurrent spontaneous abortion; TPO: anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone.

NK cells assessment and definition of abnormal NK cell levels in the study population

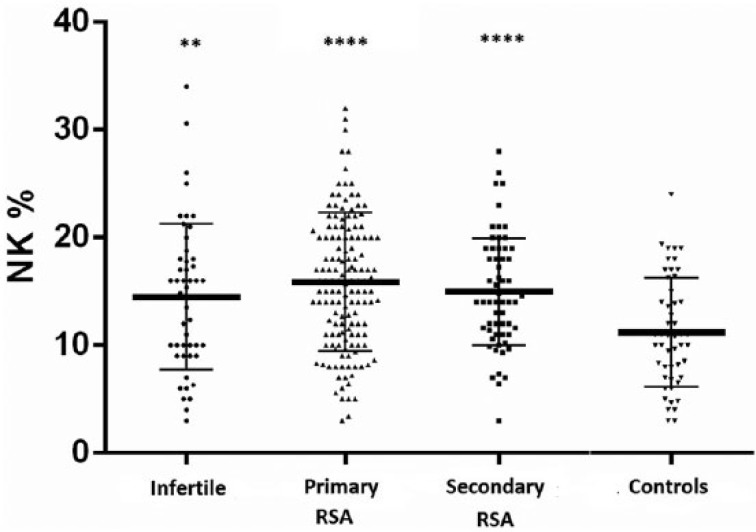

The mean percentage of NK cell levels resulted higher in the infertile (14.5 ± 6.8), primary RSA (15.8 ± 6.4), and secondary RSA (15 ± 5) when compared with the levels in the comparison group (11.2 ± 4.7, P <0.01 for the comparison with the infertile group, P <0.001 for the comparisons with both the RSA groups, Figure 1). No significant differences occurred in NK cell levels between the infertile and the primary/secondary RSA women. No correlations resulted between the mean NK cell levels and the age of the women or the number/GW of spontaneous abortions in the RSA groups.

Figure 1.

Natural killer (NK) cell levels in the study population. Natural killer (NK) cell levels (as a percentage) in infertile women (n = 49) and in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) (primary RSA, n = 145; secondary RSA, n = 65) compared with controls (n = 45). Horizontal lines indicate the mean values. Differences between mean values were determined by Student’s t-test. **P <0.01, ****P <0.001, in comparison with the controls.

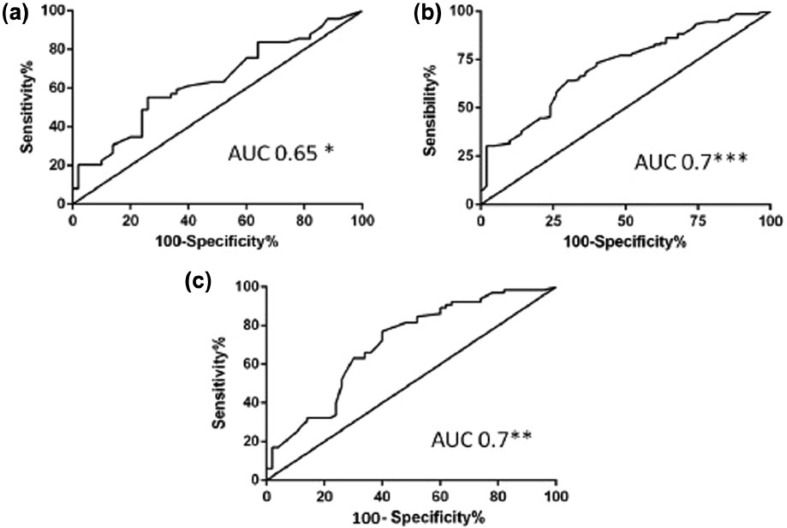

The ROC analysis and the AUC obtained using the NK cell levels observed in patients and controls showed that the assessment of NK cell levels as a diagnostic test displayed a moderate accuracy in the infertile group (AUC 0.65, 95% CI 0.5–0.8, P = 0.02, Figure 2a), the primary RSA (AUC 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.7, P <0.001, Figure 2b), and the secondary RSA (AUC 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.7, P <0.01, Figure 2c). Threshold levels for NK cell percentage were determined for all the groups of the women in the study population. The cutoff value determining the “abnormal values” resulted ⩾15% in all the groups of infertile/RSA women. The prevalence of women with NK cells levels ⩾15% was significantly higher in the infertile group (27/49, 55%, P = 0.004, OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.5–8) when compared to the comparison group (12/45, 27%). The same was registered comparing both the RSA groups (primary RSA: 82/145, 56%, P <0.001, OR 3.7, 95% CI 1.8–7.5; secondary RSA 32/65, 49%, P=0.01, OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.2–6.2) with the controls. No differences in mean age, GW, and number of spontaneous abortion were obseved between RSA women with NK ⩾15% and those with NK <15% (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Area under the curve (AUC) of the natural killer (NK) cell levels in the study groups. AUC of the NK cell levels (as a percentage) between the women with infertility and the controls (AUC 0.65, 95% CI 0.5–0.8) (a), women with primary recurrent spontaneous abortion (RSA) and the controls (AUC 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.7) (b), women with secondary RSA and the controls (AUC 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.7) (c). All the analyses showed a significance to discriminate women with infertility/RSA from the controls. *P <0.05; **P <0.01; ***P <0.001.

Analysis of women with abnormal NK cell levels according to thyroid status

According to thyroid status, women were divided in SCH (both in the presence and in the absence of non-toxic goiter), TAI (ATG and/or TPO positive), and ET.

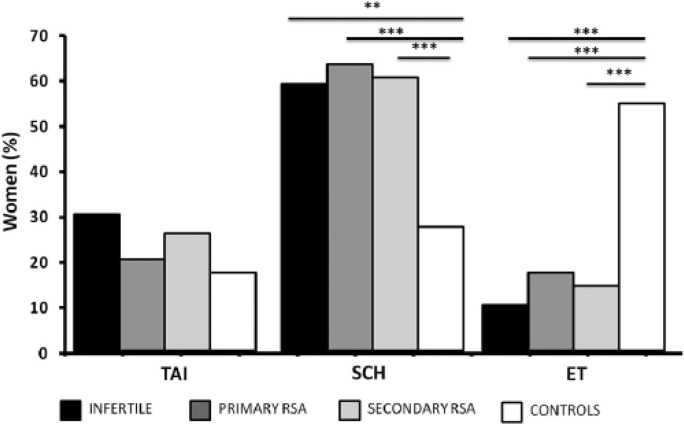

The prevalence of SCH was significantly higher in the infertile (29/49, 59.2%, P <0.001, OR 3.7, 95% CI 1.6–8.6), primary RSA (91/145, 62.7%, P <0.0001, OR 4.3, 95% CI 2–8.7), and secondary RSA (39/65, 60%, P <0.0001, OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7–8.5) when compared with the comparison group (12/45, 27%, Figure 3). On the other side, the prevalence of ET women was higher in the comparison group (24/45, 53.4%) with the respect to the other groups (infertile: 5/49, 10.2%, P <0.0001, OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.04–0.3; primary RSA: 25/145, 17.2%, P <0.0001, OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.08–0.3; secondary RSA: 9/65, 13.8%, P <0.0001, OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.05–0.3) (Figure 3). No differences in the prevalence of TAI were shown between patients (infertile: 15/49, 30.6%; primary RSA: 29/145, 20%; secondary RSA: 17/65, 26.2%) and controls (9/45, 20%, Figure 3). No difference in the prevalence of thyroid diseases were found between infertile and RSA women.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of women with thyroid disorders in the study population. The prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) was significantly higher in the infertile (29/49, 59.2%, OR 3.7, 95% CI 1.6–8.6), primary RSA (RSA, 91/145, 62.7%, OR 4.3, 95% CI 2–8.7), and secondary RSA (39/65, 60%, OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7–8.5) when compared with the comparison group (12/45, 27%). The prevalence of euthyroid (ET) women was higher in the comparison group (24/45, 53.4%) with respect to the other groups (infertile: 5/49, 10.2%, OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.04–0.3; primary RSA: 25/145, 17.2%, OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.08–0.3; secondary RSA: 9/65, 13.8%, OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.05–0.3). No differences in the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid diseases (TAI) occurred comparing groups (infertile: 15/49, 30.6%; primary RSA: 29/145, 20%; secondary RSA: 17/65, 26.2%; controls: 9/45, 20%). The contingency analyses were performed by Fisher’s test. **P <0.001; ***P <0.0001. The measure of association was obtained using OR, and CI was reported.

In a single-group analysis, women with NK cell levels ⩾15% were more prevalent in SCH group when compared to TAI (P = 0.002, OR 7, 95% CI 2–23) and ET (P <0.001) among the infertile women (Table 3). The same occurred when considering both the RSA groups, where the prevalence of women with abnormal NK cells was higher in the SCH women when compared with both the TAI and the ET women (primary RSA: P <0.0001, OR 7.3, 95% CI 3.6–15; secondary RSA: P = 0.0008, OR 7.2, 95% CI 2–22) (Table 3). Among RSA women with abnormal NK cell levels, there were no correlations between the mean NK cell levels and the GW of abortion (data not shown).

Table 3.

Women with natural killer (NK) cell levels higher than the cutoff values.

| Infertility (n = 27) | Primary RSA (n = 82) | Secondary RSA (n = 32) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAI | n (%) | 6 (22)* | 15 (18.3)† | 6 (18.75)† |

| NK % (range) | 16.3 ± 0.8 (14.5–17.4) | 20.6 ± 5 (15–32) | 16.7 ± 1.8 (15–19) | |

| SCH | n (%) | 18 (66) | 51 (62.2) | 20 (62.5) |

| NK % (range) | 21.2 ± 5.3 (14.8–34) | 19.4 ± 3.6 (15–30) | 19.5 ± 3.3 (15–26) | |

| ET | n (%) | 3 (12)† | 16 (19.5)† | 6 (18.75)† |

| NK % (range) | 19.7 ± 3.2 (16–22) | 18.8 ± 2.9 (15–25) | 18.8 ± 4.8 (15–28) |

Comparisons with SCH P <0.01.

Comparisons with SCH P <0.001.

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

The contingency analyses were performed by Fisher’s exact test.

ET: no thyroid diseases; NK: natural killer; RSA: recurrent spontaneous abortion; SCH: subclinical hypothyroidism; TAI: autoimmune thyroid diseases.

As a remark, in the comparison group the prevalence of women with abnormal NK cells was similar in the SCH women (4/12, 33%) when compared with both the TAI (3/12, 25%) and the ET (5/12, 42%). No significant correlations were observed between NK cells and both ATG/TPO and TSH levels in the study groups (data not shown).

Other results

Seventeen women of the overall cohort had ANA titer ⩾ 1:160. All of them were RSA women (12/17 primary RSA; 5/17 secondary RSA, Table 2): 11 (64.7%) had SCH; four (23.5%) had TAI; and two (11.8%) were ET. No co-morbidity or other relevant condition has been observed in that group of ANA positive patients. The prevalence of positive ANA titer in the TAI women (4/67, 5.97%) was not statistically different with respect to that observed in the SCH women (11/173, 6.35%). None of the women in the infertile group and in the comparison group were ANA positive.

Discussion

To explore possible relationships between NK cell levels and mild thyroid diseases in women with reproductive failure, we first analyzed NK cell levels in all the women enrolled. We found that both the infertile and the RSA women had significantly higher NK cell levels than controls even when the primary and secondary RSA women were considered distinctly. These results are in accordance with other studies comparing the percentage of peripheral blood NK cells in infertile/RSA women versus fertile controls.32,34 However, interestingly we demonstrated for the first time that there is no difference in NK cell levels between women with primary RSA and women with secondary RSA. Since it is well known that the natural history of most RSA women usually turns into (secondary) infertility, we decided to consider as “infertile women” only the women with primary infertility (without spontaneous abortions and/or living children). However, the common link between infertility and RSA is, likely, the autoimmunity that is usually characterized by a rather widely activated immune system. In this context, it is possible that elevated NK cell levels represent an evidence of such broadly based immune system activation and they may char-acterize women with both primary infertility and RSA according to alloimmune mechanisms of the pregnancy failure.29,30,32,34 The ROC analyses suggested that the assessment of the peripheral blood NK cell exhibits a moderate accuracy as diagnostic tool in women with reproductive failure, confirming previous data.30,34 We described by using AUC of ROC curve analysis that NK cell percentage may be a useful test to differentiate women with primary infertility or primary/secondary RSA and fertile controls. In this study, for the first time, we reported that the accuracy of the peripheral blood NK cell assessment is good even when primary and secondary RSA were considered distinctly.30,34 The cutoff value of NK cell percentage obtained in our study population resulted in accordance with data in the literature.30,31 According to the threshold value for abnormal NK cell levels, we observed that the prevalence of women with abnormal NK levels was, as expected, higher among the infertile and RSA women with the respect to the comparison group. We did not investigate subsequent pregnancy outcomes of miscarriage or failure to conceive after assisted reproductive technology and thus the possibility of a time-point dependent progressive increase of NK levels. In this context, the prognostic value of measuring peripheral blood NK or uterine NK cell parameters remains uncertain in the literature.32,36,37 More studies are needed to confirm the role of NK cell assessments as a prognostic test for women with reproductive failure.38,39 Because of such evidence, NK cell analysis and immune therapy is currently offered mainly in the context of clinical research.32 Since we aimed at assessing the possible relationship between NK cells and mild thyroid abnormalities (TAI and SCH) we evaluated the prevalence of thyroid disorders in our study cohort. SCH represented the most frequently associated condition: the OR analyses described that SCH seems to be associated with a higher risk of reproductive failure and that the absence of thyroid disorders appear to be related with a good pregnancy outcome. As a remark, the prevalence of SCH in the comparison group resulted higher than the value usually registered in the general population. This may be related to the use of both the cutoff of 2.5 mIU/L for normal basal TSH and the TRH stimulation test to define SCH in our study groups.21,22 Differently from other authors, we reported a similar frequency of TAI between the infertile and the RSA women as well as between the women with primary and secondary RSA.33 Moreover, we found the same prevalence of TAI in infertile/RSA women and in controls suggesting that this autoimmune condition is not strictly associated with a poor pregnancy outcome in our study population. It has been reported that the prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in women of reproductive age is in the range of 6–20%, being even higher in women with a history of RSA.26 In our study, almost 20% of both patients and controls resulted positive for at least one type of anti-thyroid antibody. This finding could be related to the clinical heterogeneity and to assays and thresholds used that likely contribute to the statistical heterogeneity observed in our study population with the respect to other studies.26 Moreover, since female sex as well as Caucasic ethnicity represent risk factors for TAI,40 the relatively high prevalence of TAI in our controls is conceivable. We included in the TAI group women with both normal and impaired thyroid function in accordance with the idea that the presence of anti-thyroid autoantibodies could represent the main factor leading to an increased risk of reproductive failure even in the absence of clinically overt hypothyroidism.22–26,35,41,42 In this view, the presence of thyroid autoantibodies can reflect a generalized activation of the immune system with a possible disregulation of local inflammatory process at placental–decidual environment being relevant to the clinical outcome.26 As increasing maternal age has been reported as an “independent” risk factor for infertility/RSA, we examined the difference in the mean age of women with TAI, SCH, or ET and no significant difference was found between the groups.26 Although some of the patients’ groups were relatively small, the prevalence of women with abnormal NK cell levels was higher in women with SCH compared to TAI and ET women, in both the infertile and the RSA groups. The meaning of these interesting findings was in accordance with the evidence supporting the role of thyroid function in the pathogenesis of many autoimmune disorders even in the absence of defined thyroid autoimmunity.23,42,43 Assuming that infertile/RSA women have an overactive immune system, an increased prevalence of thyroid abnormalities could be expected mainly in terms of autoimmunity (TPO and ATG antibodies).43 However, we observed that non-autoimmune thyroid dysfunction (such as SCH) is the more frequent condition among the infertile/RSA women and that SCH infertile/RSA women more frequently showed abnormal NK cells than TAI or ET women. Taken together, these data may suggest that SCH may represent not only an element potentially responsible for the poor pregnancy outcome, but also a marker of pre-existing immune abnormalities which can participate to the pathologic condition in a manner that they can be the cause or the consequence of a thyroid impairment.21,23,29,30,34,44 In this context, the TRH stimulation test, by highlighting the latent capacity of the pituitary gland to respond to exogenous TRH, can improve both the assessment of the thyroid function and the management of the pregnancy impairment in women with unexplained reproductive failure.21,34

As a remark, we reported very few patients with positive ANA titer in our study population. All of them were RSA women and they showed a similar prevalence of positive ANA titer in both the groups with and without TAI, confirming the poor association reported in the literature between TAI and ANA in women with unexplained reproductive failure.45–49 Concerning the relationship between autoimmunity and NK cells in human reproduction, the uterine blood flow is an innovative method recently suggested in the evaluation of the role of NK cells, that would be of interest in order to predict the risk of recurrent miscarriage and to measure the effects of treatment in women with infertility/RSA.50,51 We should consider that the present study suffers from several limitations:

The heterogeneity of the subjects being studied that represents a common problem with most studies in the area.34

The small number of women in the comparison group.

The lack of in vitro functional studies supporting the possible link between the NK cell abnormalities and the thyroid impairment in women with reproductive failure. Indeed, it would be interesting to analyze the expression of the activating and inhibitory receptors on NK cells in women with infertility/RSA. Evidence suggests that inhibitory and activating receptors such as killer-cells immunoglobulin-like (KIR), C-type lectin, and natural cytotoxicity receptors could play a role in the course of the systemic inflammatory response observed in several obstetrical syndromes.52,53 Women with adverse pregnancy outcome show an increased NK cell function related to the expression of lectin-like receptors such as NKG2.54 Additional research is thus eagerly awaited.

The lack of the assessment of nutritional status of women in the study including clinical / anthropometric parameters (such as body weight, waist circumference, body mass index) and other metabolic syndrome indicators (such as serum concentrations of lipids). In our study cohort, the metabolic assessment of the women was performed exclusively on the basis of the HOMA index as a measure of the insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome risk. As reported in the literature, nutritional status is able to induce metabolic and molecular adaptations with a pathological modification of the weight and an alteration of the immune regulation.55 Moreover, the nutritional status and the physical activity appear to be associated with a moderate to severe vitamin D deficit. Evidence suggests that an adequate vitamin D status may be protective against a spectrum of chronic disorders (such as autoimmune diseases) as well as infertility and adverse pregnancy outcome.56 In addition, recent evidence has demonstrated that low levels of vitamin D are associated with thyroid diseases.57

In summary, according to our data, we support the role of NK cell assessment as a diagnostic tool in women with reproductive failure and we suggest that the possible association between NK cell levels and thyroid function can be described not only in the presence of thyroid autoimmunity, but also in the presence of non-autoimmune thyroid disorders. Larger scale studies with a bio-molecular approach are needed to further substantiate our results.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2012) Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: A committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility 98: 1103–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rai R, Regan L. (2006) Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 368: 601–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen L, Quan S, Ou XH, et al. (2012) Decreased endometrial vascularity in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies associated recurrent miscarriage during midluteal phase. Fertility and Sterility 98: 1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bansal AS. (2010) Joining the immunological dots in recurrent miscarriage. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 64: 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saito S, Nakashima A, Shima T. (2011) Future directions of studies for recurrent miscarriage associated with immune etiologies. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 90: 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ellis SA, Sargent IL, Redman WC, et al. (1986) Evidence for a novel HLA antigen found on human extravillous trophoblast and a choriocarcinoma cell line. Immunology 59: 595–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robertson MJ, Ritz J. (1990) Biology and clinical relevance of human natural killer cells. Blood 76: 2421–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. (2001) The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends in Immunology 22: 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farag SS, Fehniger TA, Ruggeri L, et al. (2002) Natural killer cell receptor: New biology and insights into the graft-versus-leukemia effect. Blood 100: 1935–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. (2007) The biology of NKT cells. Annual Review of Immunology 25: 297–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perricone R, De Carolis C, Perricone C, et al. (2008) NK cells in autoimmunity: A two-edg’d weapon of the immune system. Autoimmunity Reviews 7: 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konova E. (2010) The role of NK cells in the autoimmune thyroid disease-associated pregnancy loss. Clinic Reviews in Allergy & Immunology 39: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Provinciali M, Di Stefano G, Fabris N. (1992) Improvement in the proliferative capacity and natural killer cell activity of murine spleen lymphocytes by thyrotropin. International Journal of Immunopharmacology 14: 865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cao X, Kambe F, Moeller LC, et al. (2005) Thyroid hormone induces rapid activation of Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin-p70S6K cascade through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human fibroblasts. Molecular Endocrinology 19: 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klecha AJ, Genaro AM, Gorelik J, et al. (2006) Integrative study of hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid-immune system interaction: Thyroid hormone-mediated modulation of lymphocyte activity through the protein kinase C signaling pathway. Journal of Endocrinology 189: 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mascanfroni I, Montesinos Mdel M, Susperreguy S, et al. (2008) Control of dendritic cell maturation and function by triiodothyronine. FASEB Journal 22: 1032–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Vito P, Balducci V, Leone S, et al. (2012) Nongenomic effects of thyroid hormones on the immune system cells: New targets, old players. Steroids 77: 988–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Montesinos Mdel M, Alamino VA, Mascanfroni ID, et al. (2012) Dexamethasone counteracts the immunostimulatory effects of triiodothyronine (T3) on dendritic cells. Steroids 77: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krassas GE, Poppe K, Glinoer D. (2010) Thyroid function and human reproductive health. Endocrine Reviews 31: 702–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, et al. (2010) Increased pregnancy loss rate in thyroid antibody negative women with tsh levels between 2.5 and 5.0 in the first trimester of pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 95: 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dal Lago A, Vaquero E, Pasqualetti P, et al. (2011) Prediction of early pregnancy maternal thyroid impairment in women affected with unexplained recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction 26: 1324–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vaquero E, Lazzarin N, De Carolis C, et al. (2000) Mild thyroid abnormalities and recurrent spontaneous abortion: Diagnostic and therapeutical approach. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 43: 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Carolis C, Greco E, Guarino MD, et al. (2004) Anti-thyroid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome: Evidence of reduced fecundity and poor pregnancy outcome in recurrent spontaneous aborters. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 52: 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poppe K, Velkeniers B, Glinoer D. (2007) Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Clinical Endocrinology 66: 309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Negro R, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, et al. (2011) Thyroid antibody positivity in the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with negative pregnancy outcomes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 96: 920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thangaratinam S, Tan A, Knox E, et al. (2011) Association between thyroid autoantibodies and miscarriage and preterm birth: Meta-analysis of evidence. BMJ 342: d2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aoki K, Kajiura S, Matsumoto Y, et al. (1995) Preconceptional natural-killer-cell activity as a predictor of miscarriage. Lancet 345: 1340–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perricone R, De Carolis C, Giacomelli R, et al. (2003) GM-CSF and pregnancy: Evidence of significantly reduced blood concentrations in unexplained recurrent abortion efficiently reverted by intravenous immunoglobulins treatment. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 50: 232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perricone R, Di Muzio G, Perricone C, et al. (2006) High levels of peripheral blood NK cells in women suffering from recurrent spontaneous abortion are reverted from high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 55: 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perricone C, De Carolis C, Giacomelli R, et al. (2007) High levels of NK cells in the peripheral blood of patients affected with anti-phospholipid syndrome and recurrent spontaneous abortion: A potential new hypothesis. Rheumatology 46: 1574–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee SK, Na BJ, Kim JY, et al. (2013) Determination of clinical cellular immune markers in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 70: 398–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seshadri S, Sunkara SK. (2014) Natural killer cells in female infertility and recurrent miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update 20: 429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim NY, Cho HJ, Kim HY, et al. (2011) Thyroid autoimmunity and its association with cellular and humoral immunity in women with reproductive failures. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 65: 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Triggianese P, Perricone C, Perricone R, et al. (2015) Prolactin and natural killer cells: Evaluating the neuroendocrine-immune axis in women with primary infertility and recurrent spontaneous abortion. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 73: 56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, et al. (2011) American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Thyroid Disease during Pregnancy and Postpartum: Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid 21: 1085–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katano K, Suzuki S, Ozaki Y, et al. (2013) Peripheral natural killer cell activity as a predictor of recurrent pregnancy loss: A large cohort study. Fertility and Sterility 100: 1629–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. King K, Smith S, Chapman M, et al. (2010) Detailed analysis of peripheral blood natural killer (NK) cells in women with recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction 25: 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tuckerman E, Laird SM, Prakash A, et al. (2007) Prognostic value of the measurement of uterine natural killer cells in the endometrium of women with recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction 22: 2208–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tang AW, Alfirevic Z, Quenby S. (2011) Natural killer cells and pregnancy outcomes in women with recurrent miscarriage and infertility: A systematic review. Human Reproduction 26: 1971–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mammen JS, Ghazarian SR, Rosen A, et al. (2013) Patterns of interferon-alpha-induced thyroid dysfunction vary with ethnicity, sex, smoking status, and pretreatment thyrotropin in an international cohort of patients treated for hepatitis C. Thyroid 23: 1151–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Negro R, Stagnaro-Green A. (2014) Diagnosis and management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy. BMJ 349: g4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hidaka Y, Amino N, Iwatani Y, et al. (1992) Increase in peripheral natural killer cell activity in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity 11: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Twig G, Shina A, Amital H, et al. (2012) Pathogenesis of infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss in thyroid autoimmunity. Journal of Autoimmunity 38: 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Polanski LT, Barbosa MAP, Martins WP, et al. (2014) Interventions to improve reproductive outcomes in women with elevated natural killer cells undergoing assisted reproduction techniques: A systematic review of literature. Human Reproduction 29: 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carp HJ, Meroni PL, Shoenfeld Y. (2008) Autoantibodies as predictors of pregnancy complications. Rheumatology 47 (Suppl. 3): iii6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Esplin MS, Branch DW, Silver R, et al. (1998) Thyroid autoantibodies are not associated with recurrent pregnancy loss. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 179: 1583–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shoenfeld Y, Carp HJ, Molina V, et al. (2006) Autoantibodies and prediction of reproductive failure. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 56: 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perricone C, De Carolis C, Perricone R. (2012) Pregnancy and autoimmunity: A common problem. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology 26: 47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kotlan B, Padanyi A, Batorfi J, et al. (2006) Alloimmune and autoimmune background in recurrent pregnancy loss – successful immunotherapy by intravenous immunoglobulin. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 55: 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yi HJ, Kim JH, Koo HS, et al. (2014) Elevated natural killer cell levels and autoimmunity synergistically decrease uterine blood flow during early pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology Science 57: 208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koo HS, Kwak-Kim J, Yi HJ, et al. (2015) Resistance of uterine radial artery blood flow was correlated with peripheral blood NK cell fraction and improved with low molecular weight heparin therapy in women with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 73: 175–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hong Y, Wang X, Lu P, et al. (2008) Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor repertoire on uterine natural killer cell subsets in women with recurrent spontaneous abortions. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 140: 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Colonna M, Jonjic S, Watzl C. (2011) Natural killer cells: Fighting viruses and much more. Nature Immunology 12: 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bueno-Sánchez JC, Agudelo-Jaramillo B, Escobar-Aguilerae LF, et al. (2013) Cytokine production by non-stimulated peripheral blood NK cells and lymphocytes in early-onset severe pre-eclampsia without HELLP. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 97: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Omodei D, Pucino V, Labruna G, et al. (2015) Immune-metabolic profiling of anorexic patients reveals an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory phenotype. Metabolism 64: 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S, et al. (2013) Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmunity Reviews 2013; 12: 976–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Muscogiuri G, Tirabassi G, Bizzaro G, et al. (2015) Vitamin D and thyroid disease: To D or not to D? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 69: 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]