Abstract

Chronic stress can suppress natural killer (NK) cell activity; this may also be related to the effect of stress on the neuroendocrine–immune network. Sea buckthorn (SBT) (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) is a thorny nitrogen fixing deciduous shrub, native to both Europe and Asia. It has been used as a medicinal plant in Tibetan and Mongolian traditional medicines. SBT has multifarious medical properties, including anti-fatigue as well as immunoregulatory effects. This study reports the effects of SBT oil with regard to the cytotoxicity and quantity of NK cells in the blood of a chronic-stress rat model, in addition to its mechanisms on the neuroendocrine–immune network. These results show that SBT oil, given by gavage to rats with chronic stress, could increase the following: body weight, NK cell quantities, and cytotoxicity, as well as the expression of perforin and granzyme B. The results also show that SBT oil in rats with chronic stress could suppress cortisol, ACTH, IL-1β and TNF-α levels, in addition to increasing 5-HT and IFN-γ serum levels. This leads to suggest that SBT oil, in rats with chronic stress, can increase NK cell cytotoxicity by upregulating the expression of perforin and granzyme B, thus causing associated effects of SBT oil on the neuroendocrine–immune network.

Keywords: chronic stress, natural killer cell, neuroendocrine–immune network, sea buckthorn oil

Stress has become a very influential aspect of modern life. Stress is a key factor in the onset and outcome of several psychiatric pathologies.1 At present, it is known that acute and chronic stress have profound effects on different components of the immune system, such as lymphocyte proliferation, cytokine production, and the redistribution of immune cells among the different lymphoid organs.2

Among the many indices of immune functions, natural killer (NK) cell activity and NK cell subsets have been of interest to researchers. This is because NK cells are known to be important in host defense against cancer and viral diseases. Studies have indicated that chronic stress is associated with a decrease in NK cell activity.3–5 Meta-analysis has also demonstrated a decrease in NK activity due to chronic life stress.6,7

Exposure to stressful situations is able to disrupt the normal regulation of the neuroendocrine axis. Stress activates both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Therefore, most research in this field has been pointed to the following classic stress hormones: glucocorticoids (GC), adreno-cortico-tropic-hormone (ACTH), 5-hydroxy-tryptamine (5-HT), and so on.8 These hormones have been widely proposed being responsible for the alterations in immune functions triggered by stress.9,10

So how does one improve the effects of the immune function caused by stress? Natural herbal medicine is praised for its immunomodulatory effects. Sea buckthorn (SBT) (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) is a thorny nitrogen fixing deciduous shrub, native to both Europe and Asia. Berries of SBT has been used in Tibetan, Mongolian and Chinese traditional medicines for the treatment of different diseases for more than 1000 years.11 SBT has drawn the attention of scientists because of its multifarious medicinal properties including anti-fatigue and immunoregulatory effects.12–14 All parts of the plant are considered to be a good source of bioactive substances. The ripe fruit has been reported to be a rich source in vitamins A, C, E and K, as well as in carotenoids and organic acids.14 SBT oil obtained from the sea buckthorn berries contains linoleic acid, α-linolenic acid, palmitoleic acid, sitosterol and β-carotene among others (Table 1).11 These contents all possess immunomodulatory activities.15–19

Table 1.

Major fatty acids and contents of sitosterol and β-carotene in SBT oil.

| Fatty acids (%) |

Sitosterol (mg/g) | β-carotene (mg/g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic acid (C14:0) | Palmitic acid (C16:0) | Palmitoleic acid (C16:1) | Stearic acid (C18:0) | Oleic acid (C18:1) | Linoleic acid (C18:2) | Linolenic acid (C18:3) | ||

| 0.83 | 26.87 | 27.52 | 1.2 | 33.1 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 15.0 | 6.9 |

This study reports the effects of SBT oil on NK cell quantity and cytotoxicity, in the blood of a chronic stress rat model and its corresponding mechanisms on the neuroendocrine–immune network.

Materials and methods

SBT oil

SBT oil was provided by Liaoning Dongning Pharmceutical Co., Ltd. The oil was extracted from the dried press residue (including berry flesh, seeds and peel) of SBT berry processed by aseptic supercritical carbon dioxide process. The samples were detected using a HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) in a GC/MS (5975C, Agilent Technologies, Inc). Samples were run in the column using split mode (split ratio = 10:1). The helium carrier gas was programmed to maintain a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The oven was initially set to 80°C for a duration of 3 min, then raised to 300°C at 4°C/min increments. Fatty acids were detected and identified by using FAME (Supelco, Belle Fonte, PA, USA) as the reference standard mixture. Major components of SBT oil are listed in Table 1.

Animal maintenance

Forty Wistar rats (200 ± 20g) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Liaoning, PR China). During the experimental period, the rats were housed in a room maintained under a 12 h light/dark cycle at 24°C. Rats had free access to standard laboratory pellet chow and fresh water.

Animal treatment

The rats were randomly assigned to the following four groups with 10 rats per group: A, control group; B, chronic stress model group; C, chronic stress + low-dose SBT oil group; and D, chronic stress + high-dose SBT oil group. Chronic stress was modeled by the use of restraint stress combined with exhausted swimming for a total of 21 days. Animals were required to swim for 10 min per session every odd day, in a fabricated metal cylinder, containing water with a depth of 30 cm, at a temperature of 25°C. On every even day, the animals were placed individually in PVC tubes (20.0 cm in length, 5.0 cm in diameter) for 4 h. The front wall of each tube was perforated so that the rats could breathe. The rats’ tails extended through the rear door of the tube and were fixed to the tube using adhesive tape. During the stress period, every group was given a dose of 10 mL/kg by gavage for 21 days. Group D was given 10 mL/kg of SBT oil, Groups A and B were both given 10 mL/kg of soybean oil. Group C, however, was given a mixed dose of 5 mL/kg of SBT oil, as well as 5 mL/kg of soybean oil. On the 22nd day, peripheral blood cells were obtained by heart puncture. After cervical dislocation was performed, rat spleens were collected for analysis. All experimental procedures were conducted according to the guidelines provided by the ethical committee of experimental animal care at Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shenyang, PR China).

NK cell preparation

The cells from rat spleens were pooled, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Pure splenic NK cell populations were further isolated using MACS magnetic bead separation technology. In brief, FITC-conjugated anti-rat CD161 and anti-FITC MicroBeads were used according to the manu-facturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) using the positive selection program “PosselD” on the autoMACS Pro Separator (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Purity of cells were routinely tested by FACS, and were in the range of 89–92%.

NK cell cytotoxicity

The isolated NK cells (1 × 105 cells) were placed in each well of a 96-well plate in a 50 μL RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco), and then co-cultured with YAC-1 (target) cells at an effectors-to-targets (E:T) ratio of 4:1 for 4 h. The plates were centrifuged, and 100 µL of supernatants were transferred to fresh 96-well plates. Subsequently, an LDH-substrate mixture (100 µL, content of the kit, Roche) containing tetrazolium salt INT was added to the supernatants. After lightless incubation for 30 min at room temperature, absorbency was determined at a wavelength of 492 nm against a reference wavelength of 600 nm. Lysis was calculated using the following equation:

Western blot analysis

The cells were washed three times with PBS, and then lysed in RIPA buffer in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay (Bios, Beijing, PR China). Aliquots (25 mg) were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies against perforin and granzyme B (abcam) at 4°C, for 12 h, washed extensively with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at 1:10,000 dilutions. The intensity of the protein fragments were viewed by using an X-ray image film processor (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis

Peripheral blood (100 μL) was collected into EDTA-coated tubes. Red blood cells were first lysed with FACS lysing solution, and then washed twice with PBS containing 2% FBS. The leukocytes were then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD161 (CD49b) (Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature. FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used and the data was analyzed using FlowJo software.

ELISA analysis

Whole blood was allowed to stand at room temperature for 2 h, and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm, at 4°C for 15 min. Serum was collected to detect the concentrations of cortisol, ACTH, 5-HT, IL-1β, IFN-γ and TNF-α by ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Uscn Life Science Inc., PR China). Cytokine concentrations in the respective samples were determined on the basis of standard curves, prepared using recombinant cytokines of known concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare multiple quantitative variables. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA analysis of variance, followed by Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Results

SBT oil could increase body weight in rats with chronic stress

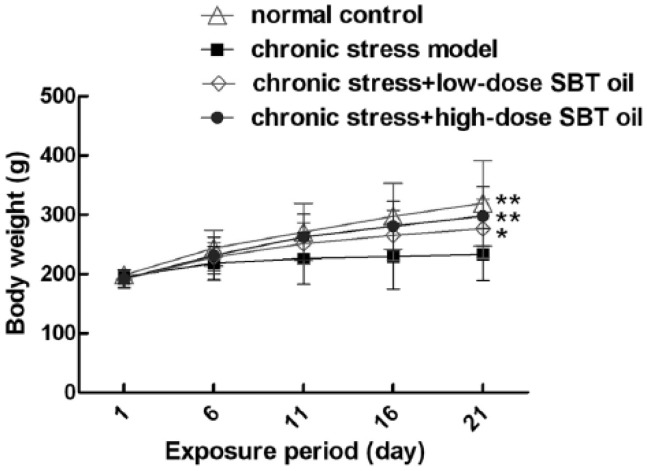

Body weight was observed in each of the four groups to different extents from day 1 to the 21st day (Figure 1). The average body weight of rats in groups A (control), C (low-dose SBT oil), and D (high-dose SBT oil) were all obviously higher than group B (model). Furthermore, there were no significant differences between group A that of group C, as well as to group A in comparison to that of group D.

Figure 1.

The effects of SBT oil on the body weight of rats with chronic stress. *Compared to group of chronic stress, P <0.05, **compared to group of chronic stress, P <0.01.

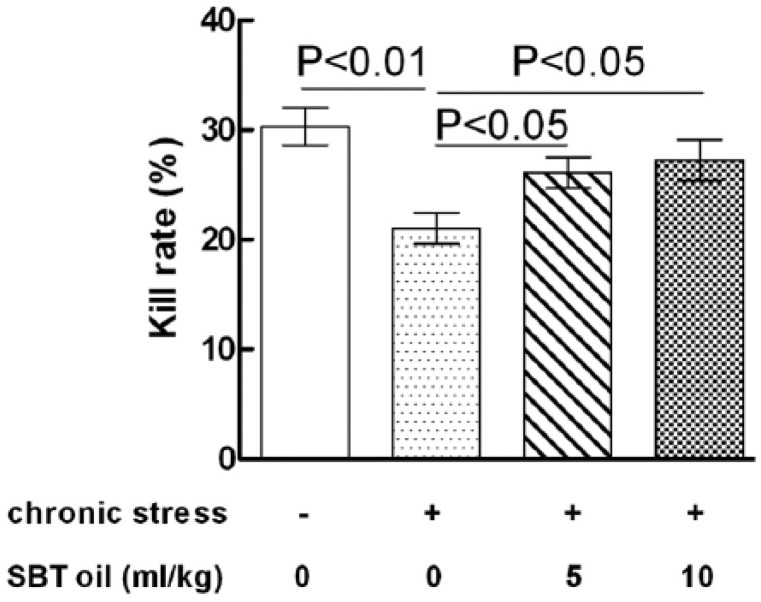

SBT oil could increase NK cell cytotoxicity in rats with chronic stress

The effects of SBT oil on NK cell cytotoxicity in rats with chronic stress are shown in Figure 2. NK cell cytotoxicity in group B (model), is significantly lower than that of group A (control). In comparison with group B, the NK cell cytotoxicity in both groups C (low-dose SBT oil group) and D (high-dose SBT oil group) greatly increased. There were no significant differences between group A with either groups C or D.

Figure 2.

The effects of SBT oil on NK cell cytotoxicity in rats with chronic stress.

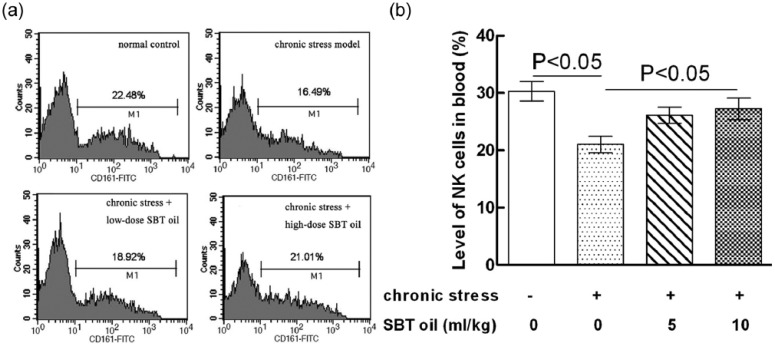

SBT oil could increase the quantity of NK cells in whole blood of rats with chronic stress

The effects of SBT oil on NK cells in blood levels of rats with chronic stress are shown in Figure 3. NK cell quantities in group B (model) were obviously lower than that of group A (control). When compared to group B (model), the NK cell quantities in group D (high-dose SBT oil) obviously increased. Furthermore, there were no significant differences between groups B (model) and C (low-dose SBT oil group) or between that of groups A, C, and, D.

Figure 3.

The effects of SBT oil on NK cell quantities in rats with chronic stress. (a) Flow cytometry analysis; (b) bands from experiments.

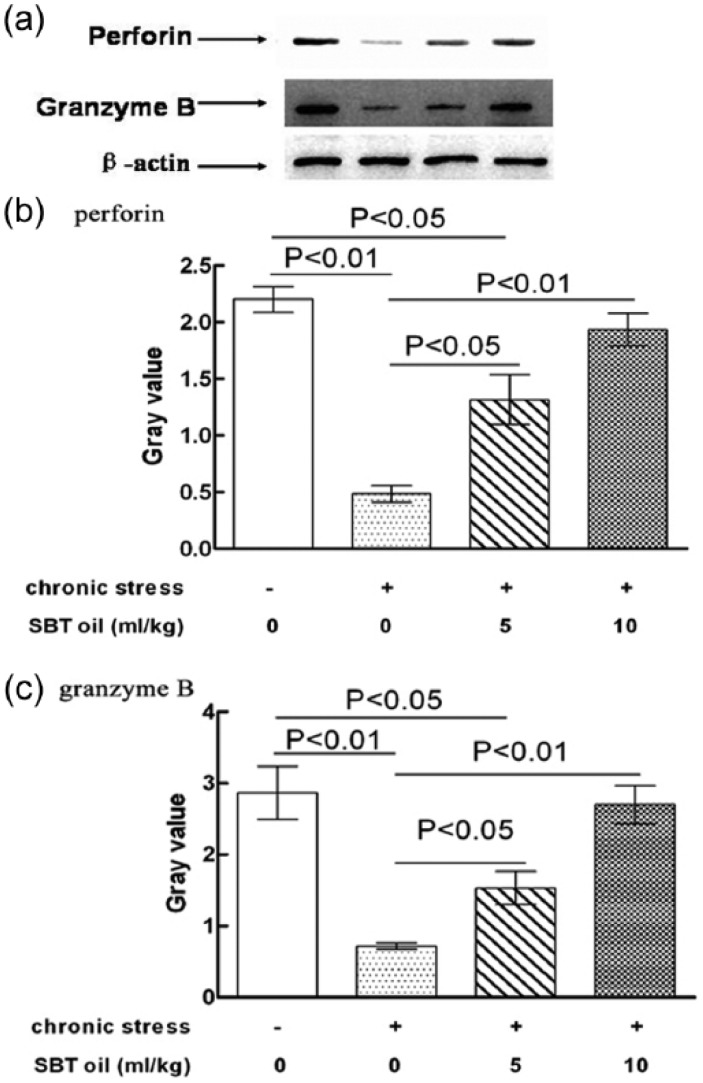

SBT oil could increase NK cell expression of both perforin and granzyme B in rats with chronic stress

The effects of SBT oil on NK cell expression in regards to perforin and granzyme B in rats with chronic stress are shown in Figure 4. NK cell perforin and granzyme B expressions in group B (model) were significantly lower than that of group A (control). Compared to group B (model), the NK cells of perforin and granzyme B expressions in groups C (low-dose) and D (high-dose SBT oil group) both increased significantly. There were no significant differences between group A (control) with that of group C (low-dose SBT oil group). Furthermore, no significant differences were found between groups A (control) and D (high-dose SBT oil group) either.

Figure 4.

The effects of SBT oil on NK cell perforin and granzyme B expressions in rats with chronic stress. (a) Western blot analysis; (b) bands from experiments for perforin; (c) bands from experiments for granzyme B.

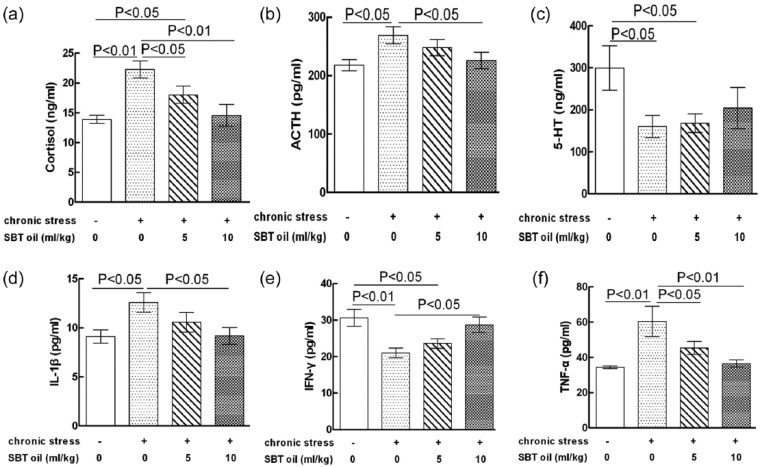

SBT oil could regulate the neuroendocrine–immunoregulatory network in rats with chronic stress

The effects of SBT oil on the neuroendocrine–immunoregulatory network in rats with chronic stress are shown in Figure 5. The results showed that cortisol, ACTH, IL-1β and TNF-α levels in serum were all increased in group B (model), that is in comparison to that of group A (control). This tendency, however, seems to be reversed by SBT oil. The 5-HT level in serum was reduced in group B (model) compared to that of group A (control), but no obvious effects were found on 5-HT levels in that of chronic stress rats given SBT oil. Chronic stress could reduce IFN-γ levels in serum significantly, compared to that of group A (control), furthermore, SBT oil could reverse such tendencies.

Figure 5.

The effects of SBT oil on the neuroendocrine–immunoregulatory network in rats with chronic stress. (a) Cortisol; (b) ACTH; (c) 5-HT; (d) IL-1β; (e) IFN-γ; (f) TNF-α.

Discussion

Stress is a complex process encompassing environmental and psychosocial factors that initiates a cascade of information-processing pathways in both the central and peripheral nervous systems.20 Chronic stress negatively affects most physiological systems due to prolonged exposure to catecholamines and glucocorticoids.21 Chronic stress has been shown to decrease cellular immune parameters, such as NK cell cytotoxicity and T-cell responses to mitogen stimulation.22 The results of this study have shown that chronic stress modeled from exhausting swimming, combined with physical restraint, could hinder body weight gain as well as reduce both NK cell quantities and cytotoxicity in comparison to rats of group A (control).

SBT and its oil have immunomodulatory and anti-stress effects.12–14 Our results have shown that SBT oil given by gavage could increase body weight gain, as well as NK cell quantities and cytotoxicity in modeled chronic stress rats.

NK cells, called “large granular lymphocytes” in early work, kill target cells through the induction of apoptosis. Perforin and granzymes are stored in cytoplasmic granules, and function after direct interaction between NK and target cells.23 Perforin, a membrane pore-forming molecule, permeabilizes cells. Granzymes, a family of serine proteases, disrupt cell cycle progression, inflict DNA damage, and dissolve the nucleus upon entrance into the cell. Granzyme B is the most abundant serine protease stored in the secretory granules of CTLs and NK cells.24 Results showed that chronic stress could reduce the expression of perforin and granzymes in group A (control) and that SBT oil could increase the expression of both perforin and granzymes in group B (model).

The effects of biobehavioral factors on the immune system are thought to be mediated in part by the sympathetic nervous system, the HPA axis, and a variety of other hormones and peptides.25,26 Results of our study showed that chronic stress could increase the level of cortisol, ACTH, IL-1β and TNF-α as well as reduce 5-HT and IFN-γ in serum compared to that of rats in group A (control). Research has shown that increased circulating concentrations of cortisol could reduce NK cytotoxicity.27 ACTH can induce the adrenal cortex to discharge cortisol.28 Increased IL-1β and TNF-α concentrations are associated with potent stimulation of the HPA axis.29 5-HT has immunomodulatory activity. Furthermore, 5-HT1A receptor antagonists, potently suppresses NK cell functions.30 This indicates that 5-HT can increase NK cells activity. IFN-γ is critical for NK cell activation. These results have shown that SBT oil could suppress the level of cortisol, ACTH, IL-1β, and TNF-α in addition to increase 5-HT and IFN-γ levels in the serum of rats with chronic stress. This shows that SBT oil could increase NK cells activity in rats with chronic stress by regulating the neuroendocrine–immune network.

Many studies have revealed that SBT oil has high contents of flavonoids, vitamin C, vitamin E and carotenoids,31,32 which may be responsible for the observed immunomodulatory and anti-stress activity. Flavonoids can improve the NK-92 cells’ cytotoxicity by upregulating the expressions of NKG2D and NKp44.33 Vitamin C, vitamin E and carotenoids can increase the activity of NK cells.34–36 It has been reported that vitamin C, vitamin E and flavones can also reduce the detrimental effects of stress.37–39

In summary, these compiled data suggest that SBT oil can increase NK cell cytotoxicity, in modeled rats with chronic stress, by the upregulation of perforin and granzyme B expression, thus bringing correlation to the effects of SBT oil on the neuroendocrine–immune network.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81303079).

References

- 1. Frick LR, Rapanelli M, Bussmann UA, et al. (2009) Involvement of thyroid hormones in the alterations of T-cell immunity and tumor progression induced by chronic stress. Biological Psychiatry 65: 935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. (2005) Stress-induced immune dysfunction: Implications for health. Nature Reviews Immunology 5: 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ciepielewski ZM, Stojek W, Glac W, et al. (2013) Restraint effects on stress-related hormones and blood natural killer cell cytotoxicity in pigs with a mutated ryanodine receptor. Domestic Animal Endocrinology 44: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morikawa Y, Kitaoka-Higashiguchi K, Tanimoto C, et al. (2005) A cross-sectional study on the relationship of job stress with natural killer cell activity and natural killer cell subsets among healthy nurses. Journal of Occupational Health 47: 378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eren S, Drugan RC, Hazi A, et al. (2012) Coping in an intermittent swim stress paradigm compromises natural killer cell activity in rats. Behavioural Brain Research 227: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herbert TB, Cohen S. (1993) Stress and immunity in humans: A meta-analytic review. Psychosomatic Medicine 55: 364–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zorrilla EP, Luborsky L, McKay JR, et al. (2001) The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: A meta-analytic review. Brain Behavior and Immunity 15: 199–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McEwen BS. (2000) Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 22: 108–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powell DJ, Moss-Morris R, Liossi C, et al. (2015) Circadian cortisol and fatigue severity in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Psycho-neuroendocrinology 56: 120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shajib MS, Khan WI. (2015) The role of serotonin and its receptors in activation of immune responses and inflammation. Acta Physiologica (Oxford, England) 213: 561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang B, Kalimo KO, Mattila LM, et al. (1999) Effects of dietary supplementation with sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) seed and pulp oils on atopic dermatitis. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 10: 622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geetha S, Sai Ram M, Singh V, et al. (2002) Anti-oxidant and immunomodulatory properties of seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides)–an in vitro study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 79: 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zheng X, Long W, Liu G, et al. (2012) Effect of seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides ssp. sinensis) leaf extract on the swimming endurance and exhaustive exercise-induced oxidative stress of rats. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 92: 736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geetha S, Singh V, Ram MS, et al. (2005) Immunomodulatory effects of seabuckthorn (Hip-pophae rhamnoides L.) against chromium (VI) induced immunosuppression. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 278: 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Shea M, Bassaganya-Riera J, Mohede IC. (2004) Immunomodulatory properties of conjugated linoleic acid. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 79: 1199S–1206S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun P, Wang J, Yang G, et al. (2010) Effects of different doses of free alpha-linolenic acid infused to the duodenum on the immune function of lactating dairy cows. Archives of Animal Nutrition 64: 504–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Talbot NA, Wheeler-Jones CP, Cleasby ME. (2014) Palmitoleic acid prevents palmitic acid-induced macrophage activation and consequent p38 MAPK-mediated skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 393: 129–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraile L, Crisci E, Cordoba L, et al. (2012) Immunomodulatory properties of beta-sitosterol in pig immune responses. International Immuno-pharmacology 13: 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jonasson L, Wikby A, Olsson AG. (2003) Low serum beta-carotene reflects immune activation in patients with coronary artery disease. Nutrition Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 13: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mustafa T. (2013) Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP): A master regulator in central and peripheral stress responses. Advances in Pharmacology 68: 445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sabban EL, Tillinger A, Nostramo R, et al. (2012) Stress triggered changes in expression of genes for neurosecretory granules in adrenal medulla. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 32: 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kubera M, Maes M, Holan V, et al. (2001) Prolonged desipramine treatment increases the production of interleukin-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, in C57BL/6 mice subjected to the chronic mild stress model of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 63: 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hodge G, Barnawi J, Jurisevic C, et al. (2014) Lung cancer is associated with decreased expression of perforin, granzyme B and interferon (IFN)-gamma by infiltrating lung tissue T cells, natural killer (NK) T-like and NK cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 178: 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prakash MD, Munoz MA, Jain R, et al. (2014) Granzyme B promotes cytotoxic lymphocyte transmigration via basement membrane remodeling. Immunity 41: 960–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ben-Eliyahu S, Shakhar G, Page GG, et al. (2000) Suppression of NK cell activity and of resistance to metastasis by stress: A role for adrenal catecholamines and beta-adrenoceptors. Neuroimmunomodulation 8: 154–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ben-Eliyahu S, Yirmiya R, Liebeskind JC, et al. (1991) Stress increases metastatic spread of a mammary tumor in rats: Evidence for mediation by the immune system. Brain Behaviour and Immunity 5: 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salak-Johnson JL, McGlone JJ, Norman RL. (1996) In vivo glucocorticoid effects on porcine natural killer cell activity and circulating leukocytes. Journal of Animal Science 74: 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beech J, Boston R, Lindborg S. (2011) Comparison of cortisol and ACTH responses after administration of thyrotropin releasing hormone in normal horses and those with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 25: 1431–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morales-Montor J, Mohamed F, Baghdadi A, et al. (2003) Expression of mRNA for interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and macrophage migration inhibitory factor in HPA-axis tissues in Schistosoma mansoni-infected baboons (Papio cynocephalus). International Journal for Parasitology 33: 1515–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frank MG, Johnson DR, Hendricks SE, et al. (2001) Monocyte 5-HT1A receptors mediate pindobind suppression of natural killer cell activity: Modulation by catalase. International Immunopharmacology 1: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu YW, Tsai CF, Chen WK, et al. (2009) Protective effects of seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) seed oil against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 47: 2281–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basu M, Prasad R, Jayamurthy P, et al. (2007) Anti-atherogenic effects of seabuckthorn (Hippophaea rhamnoides) seed oil. Phytomedicine 14: 770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han R, Wu WQ, Wu XP, et al. (2015) Effect of total flavonoids from the seeds of Astragali complanati on natural killer cell function. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 173: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Atasever B, Ertan NZ, Erdem-Kuruca S, et al. (2006) In vitro effects of vitamin C and selenium on NK activity of patients with beta-thalassemia major. Pediatric Hematology and Oncology 23: 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hanson MG, Ozenci V, Carlsten MC, et al. (2007) A short-term dietary supplementation with high doses of vitamin E increases NK cell cytolytic activity in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy 56: 973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bendich A. (1989) Carotenoids and the immune response. Journal of Nutrition 119: 112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohta Y, Yashiro K, Ohashi K, et al. (2013) Vitamin E depletion enhances liver oxidative damage in rats with water-immersion restraint stress. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 59: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vijayprasad S, Bb G, Bb N. (2014) Effect of vitamin C on male fertility in rats subjected to forced swimming stress. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 8: HC05–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fu SC, Hui CW, Li LC, et al. (2005) Total flavones of Hippophae rhamnoides promotes early restoration of ultimate stress of healing patellar tendon in a rat model. Medical Engineering & Physics 27: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]