Abstract

Cadmium toxicity can disturb brain chemistry leading to depression, anxiety, and weakened immunity. Cadmium disturbs the neurotransmitter dopamine, resulting in low energy, lack of motivation, and depression, which are predisposing factors for violence. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the ameliorative effect of grape seed extract (GSE) on the brain of 40 male albino rats after exposure to cadmium chloride (Cd) toxicity. The rats were separated into either the control group, the Cd group, the GSE group, or the GSE and Cd mixture (treated) group. The cerebrum showed evidence of degeneration of some nerve fibers and cells. Fibrosis, vacuolations, and congestion in the blood vessels were demonstrated. Satelletosis was located in the capsular cells. Immunohistochemical expression of Bax was strongly positive in the Cd group and decreased in the treated group. These histopathological changes were decreased in the brain tissue of the treated group, but a few blood vessels still had evidence of congestion. Cadmium administration increased the level of MDA and decreased MAO-A, acetylcholinesterase, and glutathione reductase (GR), while the treatment with GSE affected the alterations in these parameters. In addition, cadmium downregulated the mRNA expression levels of GST and GPx, while GSE treatment normalized the transcript levels. The expression of both dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter was downregulated in the rats administered cadmium and the addition of GSE normalized the expression of these aggression associated genes.

Keywords: cadmium chloride, cerebrum, grape seed extract (GSE), protective role, violence

Introduction

Domestic violence is widely distributed throughout the world and can occur in the streets, in houses, in schools, in workplaces, and in institutions. More than 1.6 million citizens have lost their lives and other suffered injuries due to domestic violence. Violence is among the leading causes of death for people aged 15–44 years worldwide and accounts for approximately 14% of deaths among men and 7% of deaths among women.1

Cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic element and is naturally spread in the environment. Cd is produced as an end product during the manufacture of other metals such as zinc, lead, and copper. Cd is mainly used for industrial products such as batteries and as coating for some metals and pigments.2,3 The element is also present in cigarette smoke, which represent a significant source of exposure,4 causing toxicity and is considered a source of domestic violence.5 Cd causes alteration in a variety of organs including the lung, brain, testis, kidney, liver, blood system, and bone.6,7

High Cd levels rarely affect humans but lead to serious central nervous system alterations, such as encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and hemorrhage.8,9 Subclinical Cd poisoning from chronic low-level Cd exposure remains a major health problem, especially in workers in large industrial factories.10 Cd can affect different parts of the central nervous system in albino rats. These alterations have been reported in previously published studies.11–14

Cd causes the depletion of glutathione and protein-bound sulfhydryl groups, which leads to accelerated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide ion, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide.15 The toxic effect of Cd is mediated through oxidative damage to cellular organelles by inducing the generation of ROS, which leads to lipid peroxidation, membrane protein damage, and malfunction of the anti-oxidant system. Cd exposure leads to DNA damage which in turn affects gene expression and apoptosis.16 If cells are not repaired following Cd-induced ROS they undergo apoptosis or necrosis.17

Grape seeds can be processed for the production of grape seed extract (GSE).18 GSE is a good source of flavonoids, which are potent antioxidant.19 GSE contains numerous compounds called polyphenols which contain dimers, trimers, and other oligomers (procyanidins) of catechin and epicatech. All of these compounds are types of proanthocyanidins.20 These compounds protect the body against atherosclerosis, gastric ulcer, large bowel cancer, cataracts, and diabetes. Proanthocyanidins are potent antioxidants and have cytotoxicity against a variety of tissues such as human breast tissue, lung tissue, and stomach gastric mucosa.21

Bioflavonoid and proanthocyanidins have been prepared for use in medicinal and pharmacological products.22 These compounds have antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, and immune stimulant activities. These compounds inhibit some enzyme activities such as phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and lipoxygenase.23 The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of cadmium chloride toxicity on the brain of rats and examine the possible ameliorative effect of GSE on the Cd-induced brain alterations.

Methods

Chemicals

Cadmium chloride was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). GSE was purchased from GNC standard commercial suppliers in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. GSE (formerly Grape Seed PCO Phytosome 50–120 tabs) was obtained from Health Genesis Corp. (Bay Harbor Island, FL, USA).

Animals

Male albino rats were purchased from the King Fahd Experimental Center in King AbdulAziz University, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. All of the animal procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee Office of the scientific dean of Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Experimental design

The animals were divided into four groups (10 male albino rats per group, at approximately 200 gm each rat)

Group I was fed on a balanced diet and was used as a control for 3 months.

Group II was administered 15 mg cadmium chloride /kg body weight/day dissolved in drinking water for 3 months.

Group III was administered 400 mg GSE /kg body weight/day dissolved in drinking water for 3 months.

Group IV was given a mixture of 400 mg GSE diluted in tap water in addition to 15 mg cadmium chloride /day dissolved in drinking water for 3 months.

At the end of the experiments, the brains were collected for RT-PCR, histopathological, and immunohistochemical studies. Serum samples were collected and kept in −20°C for biochemical analysis

Serum analysis

Catalase, GR, GP, and MDA were measured using commercial spectrophotometric analysis kits (Bio-Diagnostic Company, Giza, Egypt). The MAO and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) levels were measured using ELISA commercial kits (San Diego, CA, USA). All of the procedures followed the manufacturers’ instructions.

Gene expression

RT-PCR analysis of the following genes was performed and the expression levels semi-quantified: GST, GPx, MAO-A, dopamine (DD2R), 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter (5-HTT), and AChE.

RNA extraction, complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) synthesis and semi-quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the brain tissue samples described previously.24 The RNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically after measuring the OD at 260 and 280 nm. The RNA integrity was confirmed after running in 1.5% denaturated agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The 260/280 optical density ratio of all of the RNA samples was 1.7-1.9. A mixture of 3 µg total RNA and 0.5 ng oligo dT primer (Qiagen Valencia, CA, USA) was used for cDNA synthesis in a total volume of 11 µL using sterilized DEPC water and incubation in the Bio-Rad T100TM Thermal Cycle at 65°C for 10 min for denaturation. Next, 2 µL of 10X RT-buffer, 2 µL of 10 mM dNTPs, and 100 U Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MuLV) Reverse Transcriptase (SibEnzyme. Ak, Novosibirsk, Russia) were added and the total volume was adjusted to 20 µL with DEPC water. The mixture was then re-incubated in Bio-Rad thermal cycler at 37°C for 1 h, and then at 90 °C for 10 min to inactivate the enzyme. For semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis, specific primers for the examined genes (Table 1) were designed using the Oligo-4 computer program and were synthesized by Macrogen (Macrogen Company, GAsa-dong, Geumcheon-gu, Republic of Korea). PCR was conducted in a final volume of 25 µL consisting of 1 µL cDNA, 1 µL of 10 pM stock of each primer (forward and reverse), and 12.5 µL PCR master mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), the volume was adjusted to 25 uL using sterilized, deionized water. The PCR was carried out using Bio-Rad T100TM Thermal Cycle with a cycle sequence of 94°C for 5 min for one cycle, followed by 31 cycles (Table 1) consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at the specific temperature corresponding to each primer (Table 1) and extension at 72°C for 1 min with an additional final extension at 72°C for 7 min. As a reference, expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) was examined (Table 1). The PCR products were visualized under UV light after electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose (Bio Basic, Markham, ON, Canada) gel stained with ethidium bromide in TBE (Tris-Borate-EDTA) buffer. The PCR products were photographed using a gel documentation system. The intensities of the bands were quantified densitometrically using Image J software version 1.47 (http://imagej.en.softonic.com/).

Table 1.

PCR conditions and primers sequence of examined genes.

| Gene | Product size (bp) | Annealing (°C) | Direction | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GST | 570 | 55 | Forward | GCTGGAGTGGAGTTTGAAGAA |

| Reverse | GTCCTGACCACGTCAACATAG | |||

| GPx | 406 | 57 | Forward | AAGGTGCTGCTCATTGAGAATG |

| Reverse | CGTCTGGACCTACCAGGAACTT | |||

| MAOA | 492 | 60 | Forward | ATGGATGAAATGGGAAAAGAGAT |

| Reverse | TAATTGGTTTCTCTCAGGTGGAA | |||

| AChE | 785 | 55 | Forward | GACTGCCTTTATCTTAATGTG |

| Reverse | CGGCTGATGAGAGATTCATTG | |||

| DD2R | 488 | 55 | Forward | CCTGAGGACATGAAACTCTGC |

| Reverse | TAGAGGACTGGTGGGATGTTG | |||

| 5-HTT | 448 | 55 | Forward | CTCTGGCTTCGTCATCTTCAC |

| Reverse | GCTGCAGAACTGAGTGATTCC | |||

| G3PDH | 309 | 52 | Forward | AGATCCACAACGGATACATT |

| Reverse | TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA |

Histological techniques

Different brain sections were collected and processed for general and special histological stains following previously published protocols.25

Immunohistochemical techniques

The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and were dehydrated through graded concentrations of ethanol. After blocking the endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min, the sections were heated in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer in a microwave pressure cooker for 20 min. The slides were allowed to cool to room temperature, and the non-specific binding was blocked with normal horse serum for 20 min at room temperature. The sections were further incubated with the primary antibody against bax (Mouse monoclonal, Clone 2D2, Neomarkers, Fremont, CA, USA). The sections were then stained using an avidin-biotin complex (ABC) by the immunoperoxidase technique employing commercially available reagent (ABC kit, Labvision, Fremont, CA, USA); for demonstration of binding sites, ABC chromogen was applied. Phosphate buffered saline was used for rinsing between each step and finally all sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin.26

Results

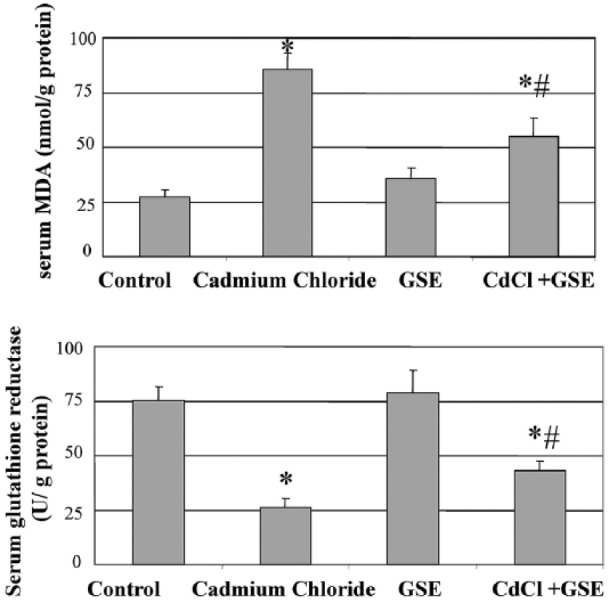

Effect of cadmium chloride on serum levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and glutathione reductase (GR) in male albino rats

Chronic administration of cadmium chloride for 3 months showed increased MDA levels (Figure 1a). GSE was shown to decrease MDA levels and prior treatment reduced the increase in MDA levels reported in the cadmium group. The activity of antioxidants in rats was significantly decreased after cadmium administration. GSE increased the GR levels and prior treatment normalized the decrease in the GR levels (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Serum changes in MDA and antioxidant levels in male albino rats after chronic administration of cadmium and protection by grape seed extract for 3 months. The values are means ± SE for 10 rats per each treatment. The serum was analyzed using colorimetric kits. *P <0.05 vs. control and #P <0.05 vs. cadmium group.

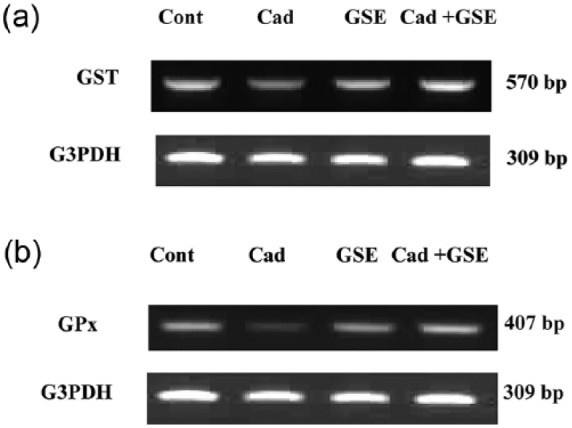

Effect of cadmium chloride on the mRNA expression of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) and peroxidase (GPx) in the brain tissue of male albino rats

As seen in Figure 2, cadmium administration for 3 months downregulated the mRNA expression of GST and GPx. The expression level was ameliorated after prior treatment with GSE.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis of GST and GPx expression in brain tissue after chronic administration of cadmium in male albino rats. The RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed (3 µg) and RT-PCR analysis was carried out for the GST and GPx genes. Densitometric analysis was carried for 10 rats. *P <0.05 vs. control.

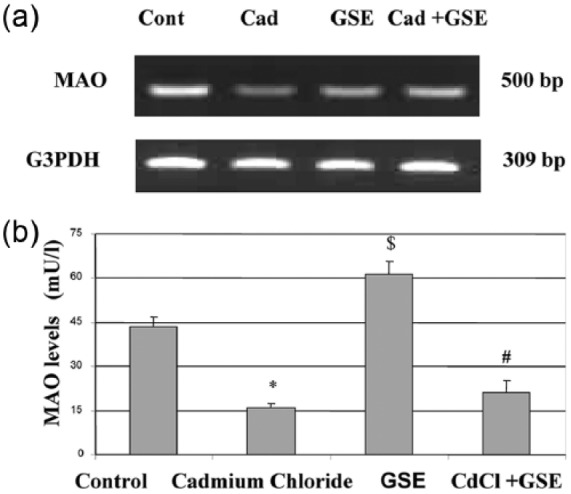

Effect of cadmium chloride on the serum levels of monoamino oxidase-A (MAO-A) and MAO-A expression in the brain of male albino rats

Cadmium administration decreased MAO-A mRNA expression and protein levels which were normalized by the addition of GSE. In addition, GSE increased MAO-A levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in MAO mRNA expression (a) and serum MAO levels (b) in male albino rats after chronic administration of cadmium and protection by GSE. (a) RT-PCR analysis of MAO expression in brain tissue after chronic administration of cadmium. The RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed (3 µg) and RT-PCR analysis was carried out for the MAO gene. (b) The values are means ± SE for 10 rats per each treatment. The serum was analyzed using colorimetric kits for MAO. *P <0.05 vs. control, $P <0.05 vs. control, and $P <0.05 vs. cadmium.

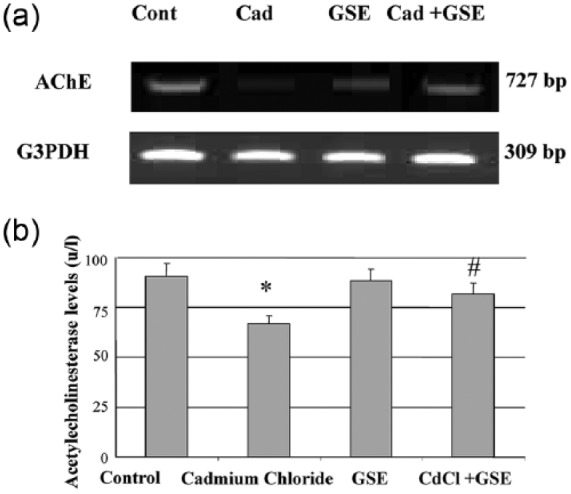

Effect of cadmium chloride on the serum levels of AChE and AChE expression in the brain of male albino rats

Cadmium administration decreased AChE mRNA expression and protein levels which were normalized by the addition of GSE (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in AChE mRNA expression (a) and serum AChE levels (b) in male albino rats after chronic administration of cadmium and protection by GSE. (a) RT-PCR analysis of AChE expression in brain tissue after chronic administration of cadmium. The RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed (3 µg) and RT-PCR analysis was carried out for the MAO gene. (b) The values are means ± SE for 10 rats per each treatment. The serum was analyzed using colorimetric kits for AChE. *P <0.05 vs. control and #P <0.05 vs. cadmium.

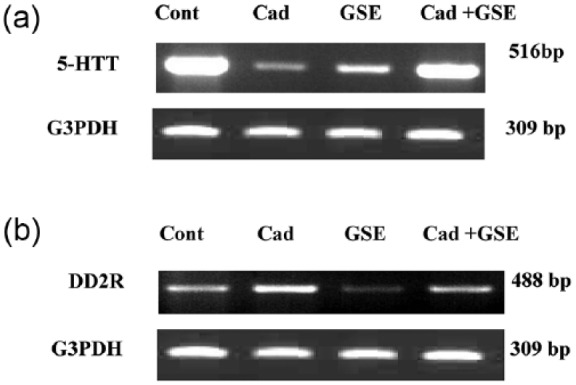

Effect of cadmium chloride on the mRNA expression of DD2R and 5-HTT in the brain tissues of male albino rats

The expression of both DD2R and 5-HTT downregulated in the cadmium administered rats. Prior treatment with grape seed was normalized 5-HTT expression. Cadmium administered increased DD2R expression and prior treatment reduced the cadmium-mediated DD2R (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

RT-PCR analysis of DD2R and 5-HTT expression in brain tissue after chronic administration of cadmium in male albino rats. The RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed (3 µg) and RT-PCR analysis was carried out for the DD2R and 5-HTT genes.

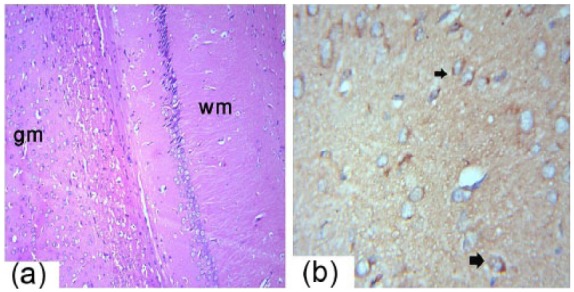

Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings

The histological structure of the control and GSE groups revealed normal brain structure. The gray matter of the adult male albino rats presented with the well-organized regularly arranged six layers, consisting of nerve cells of different sizes and shapes. The normal pattern of the white matter consisted of homogenously stained nerve fibers running down the cortex (Figure 6a). The nerve cells were different shapes and sizes and were distributed throughout the gray matter. Positive immunostaining for Bax was seen in the nerve cells and the mesothelial cells of the pia maters (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of the male albino rats brain sections showing the gray matter (gm) and white matter (wm) of the brain (a). H&E 10×. (b) Immunohistochemistry detection of Bax expression in the cerebrum (arrows) is shown at 40×.

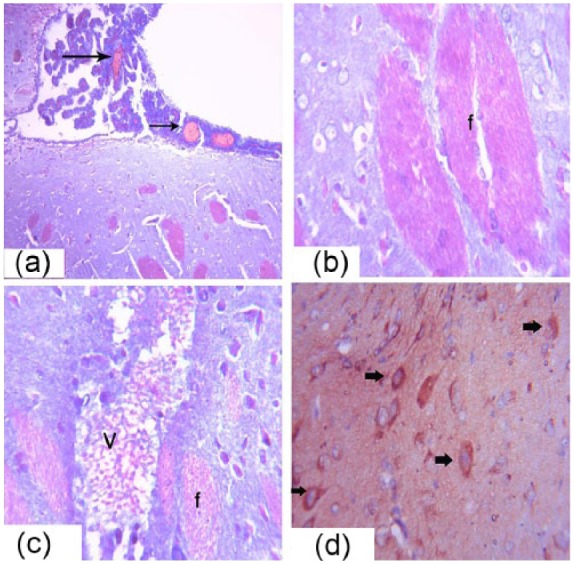

The brain tissue of the Cd group contained congested blood vessels in the brain and meninges (Figure 7a). Degeneration was reported in some nerve cells with pyknotic nuclei and fibrosis in the white matter nerve fibers (Figure 7b). Multiple small vacuoles accumulated as circumscribed areas in the architecture of the brain tissue that replaced the nerve cells (Figure 7c). Immunohistochemical analysis of Bax revealed numerous and strongly positive nerve cells (Figure 7d). Satelletosis was present in the capsular cells around the nerve cells. Congestion was present in some blood vessels (Figure 7e).

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph of the male albino rats brain sections showing, congestion of the meningeal blood vessels (arrows) (a), Masson trichrome 40×. (b) Fibrosis and degeneration in the nerve fibers and cells is shown in (f), Masson trichrome at 40×. (c) Vacuolations in the brain tissue (V) are shown, Masson trichrome at 40×. (d) Immunohistochemistry detection of Bax expression of in the cerebrum is shown (arrows), H&E 40×.

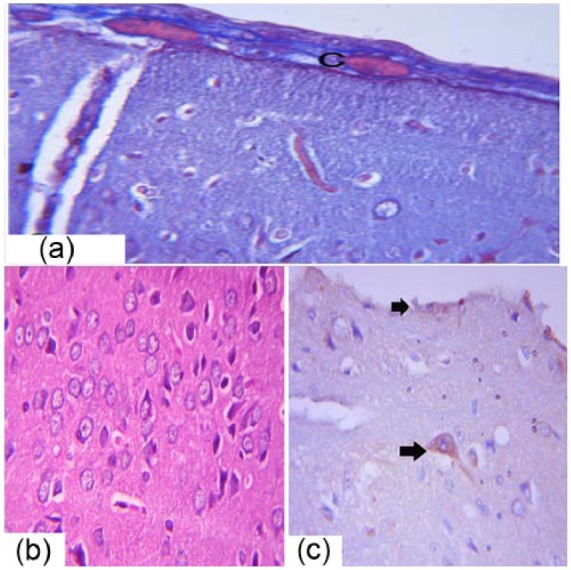

The brain tissue of the treated group showed improvement in the brain tissue but some lesions persisted. Congestion was evident in the meningeal blood vessels (Figure 8a). The nerve cells and fibers were arranged in the architecture of the brain tissue (Figure 8b). Positive immunostaining for Bax was seen in a few nerve cells and mesothelial cells of the pia maters (Figure 8c).

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph of male albino rats brain sections showing congestion in the meningeal blood vessels (C) (a), Masson trichrome 40×. (b) The arrangement of the pyramidal cells and fusiform cells of the cerebrum is shown, H&E 40×. (c) Immunohistochemical detection of Bax expression in the cerebrum is shown (arrows), 40×.

Discussion

Large factories can release Cd causing air and water pollution. Cd exposure can lead to numerous health issues such as lung tissue damage, digestive disturbance and disorders, reproductive problems and infertility, CNS disorders, and may lead to cancer.27 Cd pollution leads to the release of free radicals which result in oxidative deterioration of body lipids and proteins. In addition, Cd exposure can lead to the production and activation of procarcinogens which have been implicated in diseases development.28

High dose of Cd was shown to be toxic to the brain,11–14,29,30 causing congestion and edema of the blood vessels of the central nervous system via its effect on the endothelial lining. These findings augmented our work, showing that Cd caused blood vessels congestion and degeneration of the nerve cells and fibers. Cd toxicity alters the permeability of the blood–brain barrier.31

The examined brain tissue showed congestion in the meningeal blood vessels, degeneration of the nerve fibers and cells, and fibrosis in the cerebrum and cerebellum due to accumulation of Cd in the choroids plexus at concentrations higher than was present in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain tissues. Cd can destroy the nerve cells, oligodendrocytes, and nerve fibers in the white matter of the cerebellum.32

In the current work, Cd was shown to decreased AChE levels; conversely, a previous study,33 reported that Cd increased brain AChE activity and decreased the total brain antioxidant status in adult male rats.

AChE (EC 3.1.1.7) is an enzyme involved in cholinergic neurotransmission. This enzyme also has non-cholinergic functions as it is released with DD2R from dopaminergic neurones, implying an important interaction between these two molecules.34

Cd toxicity occurs via the inhibition acetylcholine release through the alteration calcium metabolism. The neurotoxic effect of Cd leads to the appearance of neurochemical and behavioral changes35,36 and can also lead to alterations in neurochemical mediators.37

The neurotoxic effect of Cd on the peripheral nervous system leads to degeneration of both the cells and fibers which leads to polyneuropathy (PNP).38

Cd increased the incidence of apoptosis via increased expression of Bax as determined by immunohistochemistry in the nerve cells. GSE treatment significantly decreased the incidence of apoptosis. Bax depolarizes mitochondria and induces the release of cytochrome c through openings in the outer membrane formed as a consequence of the permeability transition and loss of the mitochondrial membrane. GSE has potent anti-apoptotic properties in various tissues via suppression of pro-apoptotic proteins.39–43

Cd was shown to decrease expression and the serum level of MAO-A while GSE treatment normalized the expression and the serum level.

MAO has two forms (MAO-A and MAO-B) encoded by different genes,44 and both have different substrate and inhibitor specificities.45 MAO-A oxidizes serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) and is irreversibly inhibited by low concentration of clorgyline neurodevelopment toxicity. This toxicity includes interference with cell adhesion molecule, resulting in the misfiring of the CNS during early development and destruction of the blood–brain barrier leading to brain dysfunction, edema, nerve cell degeneration, loss of neurons, and gliosis.46

The interaction between cadmium and calcium or zinc results in interference with neurotransmission at the synapse level. These interactions induce synergistic toxicity in astrocytes which disrupts the BBB causing behavioral dysfunction in rats.47 The catabolism of neuroactive amine was shown to be controlled by MAO.48

Cd toxicity of the cerebrum can impair brain function and decrease the activity of MAO-A. Cd toxicity causes numerous health hazards in addition to the neurological and genetic disorders that can lead to violence and brain dysfunction.49

The antioxidant activity of rats was decreased significantly after cadmium administration. GSE increased GR levels and prior treatment normalized the decrease in GR levels. In addition, Cd downregulated the expression of GST and GPx while GSE normalized their expression. Cd exposure also resulted in a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio as well as the activities of GR and glucose-6-phospate-dehydrogenase (G6PDH) in various brain regions. However, the decrease in GSH/GSSG was not seen in the hippocampus and midbrain.50 Elevated ROS production, thiol and GSH reduction, and an increased GSSG level were reported. SOD, CAT, GST, GR, GPx, and G6PDH activities were diminished. These results are indications of oxidative impairment.

DD2R and 5-HTT was downregulated in the cadmium-administered rats. Prior treatment with GSE normalized 5-HTT expression. Cadmium administration increased DD2R expression and prior treatment downregulated the cadmium induced increase.

The serotonin transporter (SERT or 5-HTT) is a type of monoamine transporter protein that transports serotonin from the synaptic cleft to the presynaptic neuron. Serotonin (5-HT) controls a wide range of biological functions. In the brain, the role of serotonin as a neurotransmitter has been extensively studied.51 A key protein involved in 5-HT clearance is the membrane-bound 5-HT transporter (5-HTT), which is responsible for cellular internalization of the bioamine.52 In humans, dopamine receptor D2, also known as D2R, is encoded by the DRD2 gene. Activation of the D2 autoreceptor protected dopamine neurons from cell death induced by a toxin mimicking Parkinson’s disease pathology.53

Cadmium caused an increase in MDA levels. GSE decreased MDA levels and prior treatment reduced the increase in MDA levels reported in the cadmium group. The antioxidants activity of rats was decreased significantly after cadmium administration. GSE increased GR levels and prior treatment normalized the decrease in the GR levels.

The levels of free radicals are responsible for cell growth and maturation and affect cell components such as lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids.54,55 Free radicals oxidize polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and hydroxyl (OHS), peroxyl (ROS), and alkoxyl (ROOS) groups. The cell membrane susceptible to attack from free radicals which leads to lipid oxidation.56

Malondialdehyde (MDA) is used as an indicator for cell membrane injury. MDA is a secondary product of lipid peroxidation due to attack by free radicals and reactive oxygen.57 When RBCS membranes were exposed to Cd toxicity, lipid peroxidation increases. MDA is used as an indicator for oxidative damage in different organs including the brain and testis.58,59

GSE is major source of polyphenols, more specifically polyhydroxylated flavan-3-ols which is used for the control of different pathophysiological alterations such as homeostasis, inflammation, and detoxification. GSE can also be used in the treatment of cancer and weight loss attributed to metabolic disorders.60

Conclusion

Cadmium toxicity has a neurotoxic effect in the cerebrum represented as alterations in brain structure and function. These alterations were considered as predisposing factors for violence. Treatment with GSE can ameliorate these alterations and can lead to improved mental activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Al-Saedan Research Chair for Genetic Behavioral Disorders, Taif University, KSA, for the financial support.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (1999) Injury: A leading cause of the global burden of disease. Document WHO/HSC/PVI/99.11. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Page AL, Al-Amamy MM, Chang AC. (1986) Cadmium: Cadmium in the environment and its entry into terrestrial food chain crops. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 80: 33–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hart BA. (2000) Response of the respiratory tract to cadmium. In: Zalpus RK, Koropatnick J. (eds) Molecular Biology and Toxicology of Metals. London: Taylor and Francis, pp. 208–233. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stohs SJ, Bagchi D, Bagchi M. (1997) Toxicity of trace element in tobacco smoke. Inhalation Toxicology 9: 867–890. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization (2008) Cadmium. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Vol. 1 3rd edn. Incorporating 1st and 2nd addenda. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manca D, Ricard AC, Trottier B, et al. (1991) Studies on lipid peroxidation in rat tissues following administration of low and moderate doses of cadmium chloride. Toxicology 67: 303–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ercal N, Gurer-Orhan H, Aykin-Burns N. (2011) Toxic metals and oxidative stress. Part 1. Mechanisms involved in metal-induced oxidative damage. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 1: 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson JR. (2008) Heavy metal neurotoxicity and associated disorder: Biochemical mechanisms. Science 291: 860–867. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watenaux B, Rabinowitz T, Needer H, et al. (2009) Effects of cadmium exposure on the physiology of cerebellar neurone. Progress in Neurophysiology 48: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sidman JB, Leviton AM. (2005) Effects of cadmium exposure on the physiology of neurone. Engli J Med 356: 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olson T, Klaus B, Nguyen A, et al. (2009) Heavy metal detoxification system in the CNS. Journal of Comparative Neurology 202: 9–191. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Draff K, Peters A. (2011) Low level fetal cadmium exposure effect on neurobehavioral development in early infancy. Pediatrics 106: 1150–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graef BR. (1998) Effect of lead and cadmium on the postnatal development of the cerebellum. Society for Neuroscience 56: 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flower CA. (2006) Cadmium poisoning management. Clinical Toxicology Reviews 32: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu J, Shen HM, Ong CN. (2001) Role of intracellular thio depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species in Salvia miltiorrhiza-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Life Sciences 69: 1833–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu X, Faqi AS, Yang J, et al. (2002) 2-Bromopropane induces DNA damage, impairs functional antioxidant cellular defenses, and enhances the lipid peroxidation process in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells. Reproductive Toxicology 16: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thevenod F. (2003) Nephrotoxicity and the proximal tubule insights from cadmium. Nephron Physiology 93: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abd El, Kader MA, El-Sammad NM, Fyiad AA. (2011) Effect of grape seeds extract in the modulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity and oxidative stress induced by doxorubicin in mice. Life Sciences 8: 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahmed AAE, Fatani AJ. (2007) Protective effect of grape seeds proanthocyanidins against naphthalene-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 15: 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raina K, Singh RP, Agarwal R, et al. (2007) Oral grape seed extract inhibits prostate tumor growth and progression in TRAMP mice. Cancer Research 67: 5976–5982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bagchi D, Bagchi M, Stohs S, et al. (2000) Free radicals and grape seed proanthocyanidin extract: Importance in human health and disease prevention. Toxicology 148: 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jovanovic SV, Steenken S, Tosic M, et al. (1994) Flavonoids as antioxidants. Journal of the American Chemical Society 116: 4846–4851. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salah N, Miller NJ, Paganga G, et al. (1995) Polyphenolicflavonals as scavengers of aqueous phase radicals and chain-breaking antioxidants. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 322: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soliman MM, Attia HF, Hussein MM, et al. (2013) Protective effect of N-Acetylcystiene against titanium dioxide nanoparticles modulated immune responses in male albino rats. American Journal of Immunology 9: 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bancroft JD, Stevens A. (2002) Theory and Practice of Histological Technique. 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kiernan JA. (2008) Histological and Histochemical Methods: Theory and Practice. 4th edn. Bloxham: Scion Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh P, Chaudhary S, Patni A, et al. (2007) Effect of cadmium chloride induced genotoxicity in bone marrow chromosomes of Swiss albino mice and subsequent protective effects of Emblica officinalis and vitamin C. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology 1: 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stohs SJ, Bagchi D. (1995) Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 18: 321–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumar TA. (2008) Nerve sheath ionic channel as the primary target of cadmium toxicity. Neurotoxicology 36: 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beal RS, Singer PA, Meda MN. (2011) A consideration of age-dependent difference in susceptibility to organophosphorus and cadmium insecticides. Journal of Neurochemistry 81: 1153–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Bo, Yanli Du. (2013) Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2013: 898034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wahdan MH, Ismail AK, Saad MF, et al. (2014) Effect of cadmium exposure on the structure of the cerebellar vermis of growing male albino rat. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences 8: 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carageorgiou H, Tzotzes V, Sideris A, et al. (2005) Cadmium effects on brain acetylcholinesterase activity and antioxidant status of adult rats: Modulation by zinc, calcium and l-cysteine co-administration. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology 97: 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soreq H, Seidman S. (2001) Acetylcholinesterase–new roles for an old actor. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2: 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Desi I, Nagymajtenyi L, Schulz H. (1998) Behavioural and neurotoxicological changes caused by cadmium treatment of rats during development. Journal of Applied Toxicology 18: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Castro E, Silva E, Ferreira H, et al. (1996) Effect of central acute administration of cadmium on drinking behavior. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior 53: 687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Antonio MT, Leret ML. (2000) Study of the neurochemical alterations produced in discrete brain areas by perinatal low-level lead exposure. Life Sciences 67: 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viaene MK, Roels HA, Leenders J, et al. (1999) Cadmium: A possible etiological factor in peripheral polyneuropathy. Neurotoxicology 20: 7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sato M, Bagchi D, Tosaki A, et al. (2001) Grape seed proanthocyanidin reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis by inhibiting ischemia/reperfusion-induced activation of JNK-1 and C-Jun. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 31: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ozkan G, Ulusoy S, Alkanat M, et al. (2012) Antiapoptotic and antioxidant effects of GSPE in preventing cyclosporine A induced cardiotoxicity. Renal Failure 34: 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bayatli F, Akkuş D, Kilic E, et al. (2013) The protective effects of grape seed extract on MDA, AOPP, apoptosis and eNOS expression in testicular torsion: An experimental study. World Journal of Urology 31: 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cedó L, Castell-Auví A, Pallarès V, et al. (2013) Grape seed procyanidin extract modulates proliferation and apoptosis of pancreatic beta-cells. Food Chemistry 138: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen Q, Zhang R, Li WM, et al. (2013) The protective effect of grape seed procyanidin extract against cadmium induced renal oxidative damage in mice. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 36: 759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berry MD, Juorio LA, Paterson IA. (1994) The functional role of monoamine oxidases A and B in the mammalian central nervous system. Progress in Neurobiology 42: 375–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rebrin I, Geha RM, Chen K, et al. (2001) Effects of carboxyl-terminal truncations on the activity and solubility of human monoamine oxidase B. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276: 29499–29506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zheng W, Aschner M, Ghersi-Egea J. (2003) Brain barrier systems: A new frontier in metal neurotoxicological research. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 192: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rai A, Maurya S, Khare P, et al. (2010) Characteriza-tion of developmental neurotoxicity of as, Cd, and Pb mixture: Synergistic action of metal mixture in glial and neuronal functions. Toxicological Sciences 118:586–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shaban N Z, Masoud MS, Mawafi MA, et al. (2014) Effect of Cd, Zn and Hg complexes of barbituric acid and thiouracil on rat brain monoamine oxidase-B (in vitro). Chemico-biological Interactions 208: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zahi Fr, Rizwi JS, Haq SA, et al. (2005) Low dose mercury toxicity and human health. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 20: 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shukla GS, Srivastava RS, Chandra SV. (1988) Glutathione status and cadmium neurotoxicity: Studies in discrete brain regions of growing rats. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 11: 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ahlman H. (1985) Serotonin and carcinoid tumors. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 7 (Suppl 7): S79–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lesch KP, Wolozin BL, Estler HC, et al. (1993) Isolation of a cDNA encoding the human brain serotonin transporter. Journal of Neural Transmission General Section 91: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wiemerslage L, Schultz BJ, Ganguly A, et al. (2013) Selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons by MPP(+) and its rescue by D2 autoreceptors in Drosophila primary culture. Journal of Neurochemistry 126: 529–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sarkar S, Yadav P, Bhatnagar DJ. (1997) Cadmium-induced lipid peroxidation and the antioxidant system in rat erythrocytes: The role of antioxidants. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 11: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gupta VK, Singh W, Agrawal A, et al. (2015) Phytochemicals mediated remediation of neurotoxicity induced by heavy metals. Biochemistry Research International 2015: 534769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sarkar S, Yadav P, Trivedi R, et al. (1995) Cadmium-induced lipid peroxidation and the status of the antioxidant system in rat tissues. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 9: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jacob RA, Burri BJ. (1996) Oxidative damage and defense. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 63: 985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gutteridge JM. (1995) Lipid peroxidation and antioxidants as biomarkers of tissue damage. Clinical Chemistry 41: 1819–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stohs SJ, Bagchi D, Hassoun E, et al. (2001) Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of chromium and cadmium ions. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology and Oncology 20: 77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hasseeb MM, Al-Hizab FA, Hussein YA. (2011) A histopathologic study of the protective effect of grape seed extract against experimental aluminum toxicosis in male rat. Scientific Journal of King Faisal University (Basic and Applied Sciences) 12: 1432–1440. [Google Scholar]