Abstract

Tumor immunotherapy, capable of inducing both cellular and humoral immune responses, is an attractive treatment strategy for cancer. It has been reported that the inactivation of cell-mediated immunity by hyper-activation of humoral immunity—referred to as immune deviation—does not inhibit tumor growth. We investigated the ability of several adjuvants to elicit Thomsen-Friedenreich (T/Tn)-specific humoral immunity while avoiding immune deviation and conferring protection against tumorigenesis. T/Tn (9:1) antigen was purified from blood type O erythrocytes donated by healthy Korean volunteers. Immunization was performed using T/Tn only, T/Tn mixed with Freund’s adjuvant (T/Tn+FA), keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-conjugated T/Tn mixed with FA (KLH-T/Tn+FA), or oxidized mannan-conjugated T/Tn mixed with FA (ox-M-T/Tn+FA). Anti-T/Tn antibodies were generated in the T/Tn+FA, KLH-T/Tn+FA, and ox-M-T/Tn+FA groups. The antibody level was highest in the KLH-T/Tn+FA group. Mice immunized with ox-M-T/Tn+FA showed specific complement-dependent cytotoxicity, and were protected against T/Tn-positive mammary adenocarcinoma cell challenge, although anti-T/Tn antibody levels were the highest in the KLH-T/Tn+FA group. These results demonstrate that an ox-M-conjugated T/Tn vaccine mixed with FA can promote cellular immunity while moderating the humoral immune response, thereby effectively inhibiting tumor growth.

Keywords: T/Tn cancer vaccine, tumor immunotherapy, oxidized mannan

Immunoreactive Thomsen-Friedenreich (T) and Tn antigens are immediate precursors of human blood groups MN and O-glycosidic linkers. T and Tn are nearly always expressed in human carcinomas but not in healthy or non-cancerous diseased tissue.1–3 Incomplete glycosylation in cancer leads to the emergence of new carbohydrate and peptide backbone epitopes that are not present (exposed) on normal cells.3,4

In phase I/II clinical trials, patients with advanced adenocarcinoma were immunized with mucin (MUC)-1 immunogens. In contrast to results reported in mouse, only 30% of patients produced cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs); however, an unexpected finding was that 50% produced strong antibody (Ab) responses, with high titers of IgG1 Abs that suggested helper T cell (Th)2 activation. This inverse relationship between humoral and cellular immunity is referred to as immune deviation and is the same as the Th1/Th2 paradigm. The decision to activate the Th1 versus Th2 response is complex, since the dose of the antigen of interest may diverge from Th1-Th2 or vice versa; moreover, when a wide range of antigen concentrations is used, an additional switch often occurs—i.e. Th2-Th1-Th2.5 Monkeys immunized with MUC-1 conjugated with oxidized mannan, a carbohydrate polymer, exhibited both humoral and cellular immune responses.6 In humans, this antigen induced MUC-1 Ab and T cell responses.7–9 On the other hand, antigens that cannot induce a response but still interact with products of an immune response are incomplete immunogens that can be made fully immunogenic by coupling to a suitable carrier molecule.

In this study, we screened for immune activators that could elicit an effective immune response to the T/Tn vaccine while avoiding immune deviation.

Materials and methods

Human O red blood cell (RBC)-derived T/Tn antigen

T/Tn antigen was prepared from blood group O RBCs as previously described.1–4,10 Briefly, the MN glycoprotein was extracted from RBC stroma at room temperature using 45% aqueous phenol containing electrolytes and then purified by fractional centrifugation and ethanol fractionation.11 T epitopes on the MN glycoprotein were uncovered by specific removal of N-acetylneuraminic acid using Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase.12,13 The physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of the T antigens have been previously reported.14

Test participants

Serum samples were collected from 115 patients with breast carcinoma and 20 healthy individuals with an age range of 25–75 years (median age, 47 years). All participants were Korean and were referred to us by their surgeons. Breast cancer patients were tested prior to surgery. Healthy participants were workers at our institute and affiliated hospitals. Each cohort was tested consecutively, and pregnant women and patients with severe emotional instability or with other diseases were excluded. Blood was collected by venipuncture into anti-coagulant-free vacutainers. Serum was recovered from clotted blood by centrifugation at 1200 × g for 10 min at 18–20°C and stored at −70°C until use. All participants provided informed, written consent to participate in this study.

Preparation of T/Tn immunogens

Mannan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was oxidized to poly-aldehyde by mixing 14 mg of mannan in 1 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 6.0) and adding 100 µL of 0.1 M sodium periodate in PB for 1 h at 4°C. Following addition of 10 µL ethanediol and incubation for 30 min at 4°C, the mixture was passed through a Sephadex G-25 M PD-10 column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.0). The oxidized mannan fraction was collected and 180 µg of T/Tn were added; conjugation was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature as previously described.5,15,16 Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) was conjugated to T/Tn using the Imject Immunogen EDC Conjugation kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), and the conjugate was purified by gel filtration using the provided columns. Conjugation was confirmed by measuring absorbance at 280 nm.17

Immunization and tumor challenge

Female A/J mice (aged 6–8 weeks) were obtained from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). Mice were divided into four groups and immunized by intraperitoneal injection with one of the following: 5 μg T/Tn only, 5 μg T/Tn mixed with Freund’s adjuvant (T/Tn+FA; Sigma-Aldrich), 5 μg KLH-conjugated T/Tn mixed with FA (KLH-T/Tn+FA), or 5 μg oxidized mannan-conjugated T/Tn mixed with FA (ox-M-T/Tn+FA). Animals were given booster injections on days 10 and 17 with the same immunogens.5,15,18 Five days after the last immunization, mice were immune-challenged by subcutaneous injection of 103 TA3HA tumor cells.

Elicitation of anti-T/Tn antibodies

Mice were bled 3 days after the final injection and 1 month after tumor challenge. A U8 Maxisorp plate (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) was coated overnight at 4°C with 5 μg/mL T/Tn in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a U8 Polysorp plate (Nalge Nunc) was coated with 1 μg/mL affinity-purified goat anti-human or mouse IgM specific for Fc5μ fragment (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6), which was used to prepare the solid phase for capturing human or mouse IgM. Non-specific binding was blocked with 200 µL of 0.2% Tween 20-PBS and 250 µL of 10% sucrose-PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The serum of human or mice was serially diluted with 1% bovine serum albumin and 4% Tween 20-PBS and added to the plate, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with 0.1% Tween 20-PBS, biotin-conjugated goat anti-human or mouse IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch) was added for 0.5 h at room temperature. The plate was washed and bound secondary antibody was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK) and the chromogenic substrate 3,3’5,5’-tetramethyl benzidine solution with hydrogen peroxide (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The absorbance was determined as the optical density (OD) at 450 nm minus the OD at 620 nm (OD450−620) using a Multiskan EX/RC (Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland).10 The results were analyzed based on QME, which was calculated as the ratio of anti-T IgM to total IgM with the following formula: QME = (OD450−620 of anti-T IgM)2 / (OD450− 620 of total IgM) × 100.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)

Mice were bled 3 days after the final injection and 1 month after tumor challenge. TA3HA tumor cells (103) were seeded in triplicate in a V-bottomed 96-well plate (Nalge Nunc) containing sera (1:10) from immunized mice for 1.5 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After washing with Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μL of the same medium were added to each well containing targets with or without guinea pig complement, followed by incubation for 16 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. A 50 μL volume of supernatant was transferred to a fresh 96-well flat-bottomed plate, and lactate dehydrogenase activity was determined using the CytoTox96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The percentage specific lysis was determined as OD450−620 using a Multiskan EX/RC plate reader.10 The results were analyzed as ([OD450−620 of supernatant with guinea pig complement] – [OD450− 620 of supernatant without complement]) / (OD450− 620 of supernatant without both serum and complement) × 100%.

Results

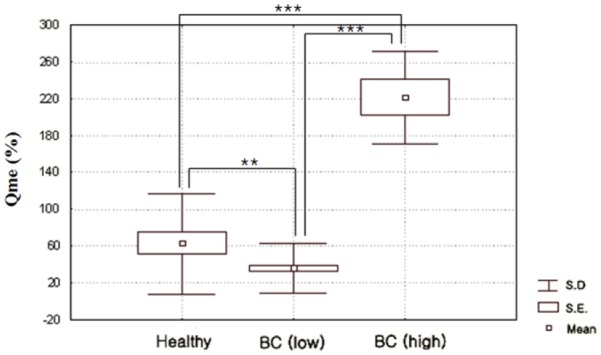

Anti-T/Tn immunity in breast cancer patients

Sera from 135 human participants (115 breast carcinoma patients and 20 healthy controls) were analyzed by obtaining QME based on the anti-T/Tn IgM and total IgM contents. QME values <7.0 were observed in 8/115 breast carcinoma patients; values >60.0 were observed in 107/115 breast carcinoma patients; and values were in the range of 7.0–14.0 in healthy participants (P <0.001; Figure 1). These results confirm that QME values can be used to distinguish between carcinoma patients and controls and indicate that anti-T/Tn immunity is related to tumorigenicity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of human anti-T IgM quotient (QME) in sera of 115 patients with breast carcinoma (BC) and 20 healthy individuals (control). BC (low) and BC (high) represent BC patients showing QME values that are lower and higher, respectively, than in controls. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001.

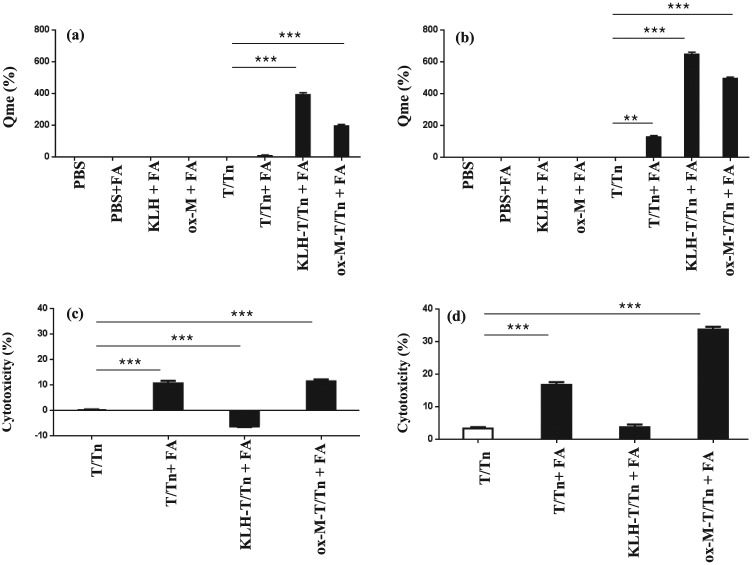

T/Tn-specific humoral immunity

Immunogenicity was examined in four groups of mice (n = 5 each) immunized with T/Tn, T/Tn+FA, KLH-T/Tn+FA, or ox-M-T/Tn+FA (with each animal receiving 5 μg of T/Tn). Anti-T/Tn Abs were induced by T/Tn (Figure 2a) and persisted for 1 month after tumor challenge (Figure 2b), with the highest Ab levels (QME) observed in the KLH-T/Tn+FA group.

Figure 2.

Humoral immunity after T/Tn immunization. (a, b) Specific anti-T/Tn antibodies were detected in sera 3 days after the final injection (a) and 1 month after tumor challenge (b). Diluted serum (1/104) was transferred to plates coated with T/Tn or anti-IgM to detect T/Tn-specific antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (c, d) CDC in sera 3 days after the final injection (c) and 1 month after tumor challenge (d). Mice (n = 5 per group) were bled 3 days after the final injection and 1 month after tumor challenge; 103 TA3HA tumor cells were incubated with sera (1:10) from immunized mice with or without guinea pig complement, and the supernatants were assayed for lactate dehydrogenase activity. The experiment was performed in triplicate. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001.

CDC

CDC was investigated in sera from mice immunized against TA3HA cells. CDC was highest in the ox-M-T/Tn+FA group, although the T/Tn Ab level was the highest in KLH-T/Tn+FA group (Figure 2c, d). T/Tn Ab and CDC levels did not differ between the T/Tn+FA and control (T/Tn) groups. These trends persisted for over 1 month after immunization.

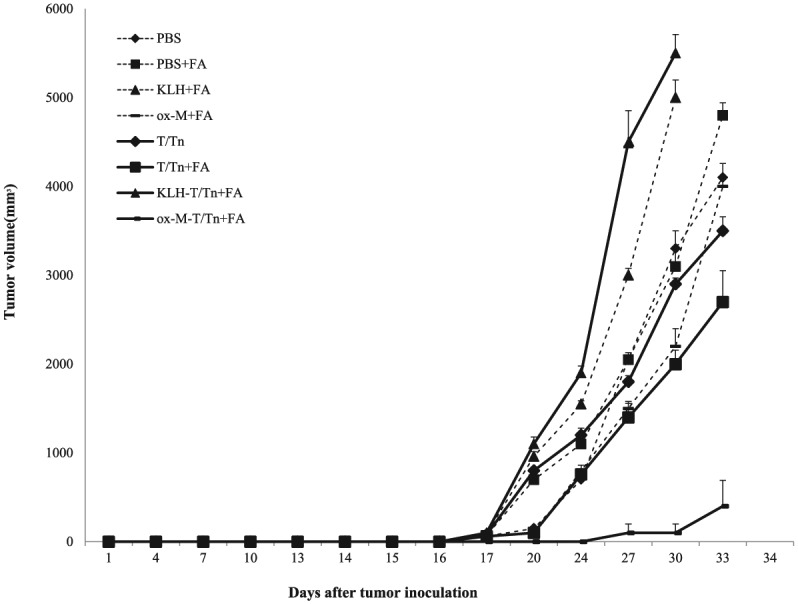

Tumor protection

Mice were subcutaneously injected with 103 TA3HA cells 5 days after the third immunization. The ox-M-T/Tn group showed significantly reduced tumor growth as compared to the other groups (Figure 3); moreover, the survival rate was prolonged in these animals and 2/5 mice did not grow tumors (data not shown). No protective effect was observed in the KLH-T/Tn+FA immunized group, even though these mice had the highest anti-T/Tn Ab levels (Figure 2a, b).

Figure 3.

Anti-tumor protection by immunization. A/J mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized with T/Tn only, T/Tn mixed with FA (T/Tn+FA), KLH-T/Tn mixed with FA (KLH-T/Tn+FA), or oxidized mannan-T/Tn mixed with FA (ox-M-T/Tn+FA). Mice were inoculated with 103 TA3HA cells by subcutaneous injection 5 days after the third injection. Tumor size was examined every other day and tumor volume (mm3) was calculated as length × width × depth (mm). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Discussion

T/Tn antigen has been shown to be immunogenic, effective,19 and safe in the prevention of breast cancer recurrence.20–22 Immunization with T/Tn alone generated humoral and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses without providing tumor protection.1,2 Many studies have attempted to improve T/Tn cancer vaccines by conjugating carrier molecules, modifying antigens, or using antigen-presenting cells.23–25 For instance, it has been suggested that a humoral response can be elicited using a synthetic multiple antigenic glycopeptide displaying a tri-Tn glycotope.3,24,26 However, immune deviation remains a challenge in clinical settings, since naturally occurring antibodies in humans bind to the immunotherapeutic agent, resulting in the generation of antibodies that can inhibit the activity of CTLs.26

This study aimed to establish a tumor vaccine formula that could avoid immune deviation. T/Tn caused immune deviation owing to the presence of anti-T/Tn antibodies in breast cancer patients, which suggested that anti-T/Tn immune response is related to tumorigenicity. Based on these results, we tested various T/Tn vaccines (T/Tn+FA, KLH-T/Tn+FA, and ox-M-T/Tn+FA) that could potentially overcome the ineffective anti-T/Tn immune response. T/Tn-specific antibodies were generated following immunization, with the highest levels observed in the KLH-T/Tn+FA group. However, CDC was higher in mice immunized with ox-M-T/Tn+FA as compared to KLH-T/Tn+FA, indicating that the anti-T/Tn humoral response is not proportional to the level of antibodies. In addition, tumor protection was observed only in the ox-M-T/Tn+FA group. We therefore conclude that ox-M-T/Tn+FA is the best T/Tn vaccine formula to prevent tumor growth among those tested, since it avoids immune deviation while inducing both anti-T/Tn humoral and cellular immune responses.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant for the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (no. 2016005276).

References

- 1. Springer GF, Desai PR, Tegtmeyer H, et al. (1994) T/Tn antigen vaccine is effective and safe in preventing recurrrence of advanced human breast carcinoma. Cancer Biotherapy 9: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Springer GF. (1997) Immunoreactive T and Tn epitopes in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and immunotherapy. Journal of Molecular Medicine 75: 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lo-Man R, Bay S, Vichier-Guerre S, et al. (1999) A fully synthetic immunogen carrying a carcinoma-associated carbohydrate for active specific immunotherapy. Cancer Research 59: 1520–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang BL, Springer GF, Carlstedt SC. (1997) Quantitive computerized image analysis of Tn and T(Thomsen-Friedenreich) epitopes in prognostication of human breast carcinoma. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 45: 1393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Apostolopoulos V, Pietersz GA, Mckenzie IF. (1996) Cell-mediated immune responses to MUC1 fusion protein coupled to mannan. Vaccine 14: 930–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaughan HA, Ho DW, Karanikas VA, et al. (1999) Induction of humoral and cellular responses in cynomolgus monkeys immunized with mannan-human MUC1 conjugates. Vaccine 17: 2740–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karanikas V, Hwang LA, Pearson J, et al. (1997) Antibody and T cell responses of patients with adenocarcinoma immunized with mannan-MUC1 fusion protein. Journal of Clinical Investigation 100: 2783–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karanikas V, Lodding J, Maino VO, et al. (2000) Flow cytometric measurement of intracellular cytokines detects immune responses in MUC1 immunotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research 6: 829–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karanikas V, Thynne G, Mitchell P, et al. (2001) Mannan mucin-1 peptide immunization: Influence of cyclophosphamide and the route of injection. Journal of Immunotherapy 24: 172–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Desai PR, Ujjiainwala LH, Carlstedt SC, et al. (1995) Anti-Thomsen-Frienderich (T) antibody-based ELISA and its application to human breast carcinoma detection. Journal of Immunological Methods 188: 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Springer GF, Nagai Y, Tegtmeyer H. (1966) Isolation and properties of human blood-group NN and meconium-Vg antigens. Biochemistry 5: 3254–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Springer GF, Desai PR. (1975) Depression of Thomsen-Friedenreich (anti-T) antibody in humans with breast carcinoma. Naturwissenschaften 62: 302–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Springer GF, Desai PR, Scanlon EF. (1976) Blood group MN precursors as human breast carcinoma-associated antigens and ‘naturally’ occurring human cytotoxins against them. Cancer 37: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Springer GF, Desai PR. (1977) Cross-reacting carcinoma associated antigens with blood group and precursor specificities. Transplant Proceedings 9: 1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Apostolopoulos V, Pietersz GA, Loveland BE, et al. (1995) Oxidative/reductive conjugation of mannan to antigen selects for T1 or T2 immune response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92: 10128–10132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pietersz GA, Li W, Popovski V, et al. (1998) Parameters for using mannan-MUC1 fusion protein to induce cellular immunity. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 45: 321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sandmaier BM, Oparin DV, Holmberg LA, et al. (1999) Evidence of a cellular immune response against sialyl-Tn breast cancer and ovarian cancer patients after high-dose chemotherapy, stem cell rescue, and immunization with Theratope STn-KLH cancer vaccine. Journal of Immunotherapy 22: 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zöller M, Christ O. (2001) Prophylactic tumor vaccination: Comparison of effector mechanisms initiated by protein versus DNA vaccination. Journal of Immunology 166: 3440–3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Springer GF. (1984) T and Tn, general carcinoma autoantigens. Science 224: 1198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slovin SF, Ragupathis G, Adluri S, et al. (1999) Carbohydrate vaccines in cancer: Immunogenicity of a fully synthetic globo H hexasaccharide conjugate in man. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96: 5710–5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dahiya R, Itzkowitz SH, Byrd JC, et al. (1992) Mucin oligosaccharide biosynthesis in human colonic cancerous tissues and cell lines. Cancer 70: 1467–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y, Choundhury P, Cabral CM, et al. (1999) Oligosaccharide modification in the early secretory pathway directs the selection of a misfolded glycoprotein for degradation by the proteasome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274: 5861–5867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bay S, Lo-Man R, Osinaga E, et al. (1997) Preparation of a multiple antigen glycopeptide (MAG) carrying the Tn antigen. A possible approach to a synthetic carbohydrate vaccine. Journal of Peptide Research 49: 620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang S, Zhang HS, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. (1997) Selection of tumor antigens as targets for immune attack using immunohistochemistry: II. Blood group-related antigens. International Journal of Cancer 73: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo-Man R, Vichier-Guerre S, Bay S, et al. (2001). Anti-tumor immunity provided by a synthetic multiple antigenic glycopeptide displaying a tri-Tn glycotope. Journal of Immunology 166: 2849–2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Apostolopoulos V, Xing PX, Mckenzie IF. (1994) Murine immune response to cells transfected with human MUC1: Immunization with cellular and synthetic antigens. Cancer Research 54: 5186–5193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]