Abstract

To date, topical therapies guarantee a better delivery of high concentrations of pharmacologic agents to the soft periodontal tissue, gingiva, and periodontal ligament as well as to the hard tissue such as alveolar bone and cementum. Topical hyaluronic acid (HA) has recently been recognized as an adjuvant treatment for chronic inflammatory disease in addition to its use to improve healing after dental procedures. The aim of our work was to systematically review the published literature about potential effects of HA as an adjuvant treatment for chronic inflammatory disease, in addition to its use to improve healing after common dental procedures. Relevant published studies were found in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Ovid using a combined keyword search or medical subject headings. At the end of our study selection process, 25 relevant publications were included, three of them regarding gingivitis, 13 of them relating to chronic periodontitis, seven of them relating to dental surgery, including implant and sinus lift procedures, and the remaining three articles describing oral ulcers. Not only does topical administration of HA play a pivotal key role in the postoperative care of patients undergoing dental procedures, but positive results were also generally observed in all patients with chronic inflammatory gingival and periodontal disease and in patients with oral ulcers.

Keywords: burning mouth, gingivitis, healing, hyaluronan, hyaluronic acid, implant, mucositis, oral mucous regeneration, oral wound, periodontitis, sodium hyaluronate, stomatitis, teeth

Introduction

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan with a high molecular weight of 4000-20,000,000 Da. The structure of HA consists of polyanionic disaccharide units of glucuronic acid and N-acetyl glucosamine connected by alternating bl-3 and bl-4 bonds. It is a linear polysaccharide of the extracellular matrix of connective tissue, synovial fluid, embryonic mesenchyme, vitreous humor, skin, and many other organs and tissues of the body.1

HA is a key element in the soft periodontal tissues, gingiva, and periodontal ligament, and in the hard tissue, such as alveolar bone and cementum.2 It has many structural and physiological functions within these tissues.

It can play a regulatory role in inflammatory response: the high-molecular-weight HA synthesized by hyaluronan synthase enzymes in the periodontal tissues, gingiva, periodontal ligament, and in alveolar bone3 undergoes extensive degradation to lower molecular weight molecules in chronically inflamed tissue, such as gingival tissue inflammation4 or in the postoperative period after implant or sinus lift surgery.

High-molecular-weight HA is fragmented under the influence of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including the superoxide radical and hydroxyl radical species observed during periodontal diseases;5 these radicals are generated primarily by infiltrating polymorphonuclear leukocytes and other inflammatory cells during bacterial phagocytosis.

Low-molecular-weight fragments play a role in signaling tissue damage and mobilizing immune cells, while the high-molecular-weight HA suppresses the immune response preventing excessive exacerbations of inflammation.6

Low-molecular-weight HA appears to be particularly prominent in the gingival tissues of patients during the initial stages of periodontitis,7 possibly as a result of the action of bacterial enzymes (hyaluronidases).8

It supports the structural and homeostatic integrity of tissues9 regulating osmotic pressure and tissue lubrication.

HA is one of the most hygroscopic molecules known in nature. When HA is incorporated into an aqueous solution, hydrogen bonding occurs between adjacent carboxyl and N-acetyl groups; this feature allows HA to maintain conformational stiffness and to retain water.

HA also presents important viscoelastic properties reducing the penetration of viruses and bacteria into the tissue.10

The molecule is also a key component in the series of stages associated with the wound-healing process in both mineralized and non-mineralized tissues (inflammation, granulation tissue formation, epithelium formation, and tissue remodeling).11,12

As a consequence of the many functions attributed to HA, advances have been made in the development and application of HA-based biomaterials in the treatment of various inflammatory conditions.9

Therefore, based on the multifunctional roles that HA has in wound healing generally, and that gingival and bone healing follow similar biological principles, it is conceivable that HA has comparable roles in the healing of the mineralized and non-mineralized tissues of the periodontium.11,13

To date, the use of HA is widely spread in several other branches of medicine and neither contraindications nor interactions with drugs have been reported.14–17

We conducted in June 201518 a systematic review on the potential benefits of topical HA in the treatment of both acute and chronic inflammatory diseases of the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT). In recent years, formulations of HA have been developed for topical administration as a coadjutant treatment in acute and chronic tooth and gingival disease, such as in the healing of tissue after oral surgery, based on the large quantity of evidence based on data available on the role of HA in the field of dentistry in animal models.19

In the literature, there are some reviews on the role of HA in the field of dentistry. However, these studies are not complete and cover only some clinical applications such as HA application in periodontal disease.20

The aim of the study is: to systematically review the published literature regarding all the therapeutic effects of HA on acute and chronic inflammatory disease in oral cavity; to clarify and classify the main application areas of HA in dentistry, the pathophysiological basis, and the schedule of postoperative HA application; and to evaluate the most effective parameters of HA use in the field of odontostomathology.

Methods

Research and study selection

Relevant published studies were searched for in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Ovid using either the following keywords or, in case of the PubMed database, medical subject headings: (“hyaluronic acid” and “periodontitis”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “gingivitis”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “mucositis”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “implant”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “ teeth”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “ gingiva”), (“hyaluronic acid “ and “oral mucous regeneration”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “oral wound”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “stomatitis”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “healing”), (“hyaluronic acid” and “oral ulcers”), and (“hyaluronic acid” and “oral scars”) with no limit selected for the year of publication.

Literature search was performed according to PRISMA guidelines with the following main eligibility criteria: only English; human controlled trials; and effect size of HA evaluated histologically or clinically in patients with dental disease.

Literature reviews, technical notes, letters to editors, and instructional course were excluded.

Two authors (CM and MA) independently assessed the full-text version of each publication, making their selection on the basis of content and excluding papers that did not include the specifically required content.

The reference lists of articles that meet the first criteria were fully reviewed to identify useful articles that were not included in the initial electronic search.

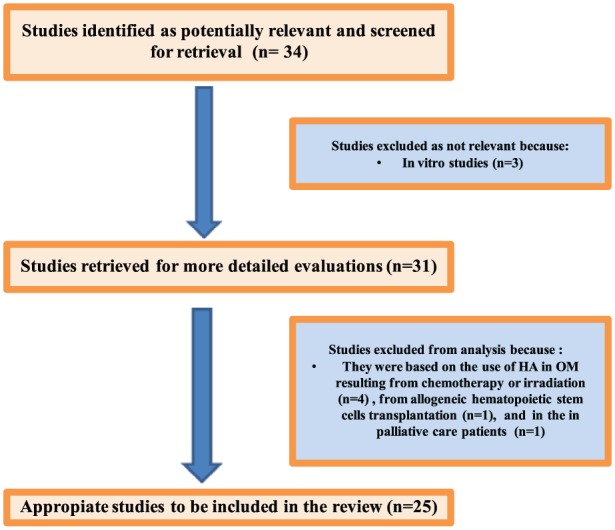

During the research phase, in each of the journals, articles strictly coherent with the topic were first identified, while studies on animal models were excluded after the primary selection. Similarly, in vitro studies were excluded at this stage.

Studies that were based on the use of HA in oral mucositis resulting from chemotherapy or irradiation, from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells transplantation, and in the treatment of palliative care patients were subsequently removed from the selected list.

At the end of our study selection process, 25 relevant publications were included, as showed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of inclusion of the studies.

Results

Features of each single study are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of each study.

| Authors | Mean age | HA group | Control group | Treatment | Parameters evaluated | Clinical evidences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA in gingivitis | ||||||

| Jentsch et al. | 50 male patients (29.9 ± 10.5 years) | 25 patients with 0.2% HA (Verum group) | 25 patients with placebo gel (placebo group) | The patients applied 1 mL of the gel (Verum or placebo gel) on the inflamed area of the buccal gingiva | Clinical indices (approximal plaque index [API], Turesky plaque index, and the papilla bleeding index [PBI] and crevicular fluid variables [peroxidase, lysozyme]) were determined at baseline and after 4, 7, 14, and 21 days | The Verum group showed significant improvement for the plaque indices beginning with day 4 and the PBI beginning with day 7 than the placebo group. Also in the Verum group, the crevicular fluid variables had a great improvement in the center of the inflammation area |

| Both groups had significant decreases in peroxidase and lysozyme activities after 7, 14, and 21 days | ||||||

| Pistorius et al. | HA group (32.8 ± 11.3) Control group (31.3 ± 9.3) | 40 patients | 20 patients | HA group used a spray containing HA 5 times daily for 1 week. Control group did not use placebo solution | The clinical parameters DMF-T (decayed, missed, filled teeth) index, API, sulcus bleeding index, PBI, and gingival crevicular fluid were measured at baseline, after 3 days, and after 7 days | The clinical parameters DMF-T (decayed, missed, filled teeth) index, API, sulcus bleeding index, PBI, and gingival crevicular fluid were measured at baseline, after 3 days, and after 7 days |

| A reduction in the sulcus bleeding index of the HA group was noted at T2 and at T3 | ||||||

| The PBI values and the gingival crevicular fluid showed significant reductions in the HA group | ||||||

| HA in chronic periodontitis | ||||||

| Mesa et al. | 21 patients (mean age 44.5 years) | Test sites received HA gel while contralateral site placebo | The test and control gels were applied topically, twice a day for 1 month | At 30 days after treatment, a gingival biopsy was taken for histopathological and immunohistochemical study, in order to determine the expression of Ki-67 and to evaluate the inflammatory infiltrate | HA gel treatment induced a significant reduction in the proliferation index of the gingival epithelium and fibroblastic cells | |

| Sahayata et al. | 105 patients with chronic plaque induce gingivitis divided into three groups: negative control group (35 patients); placebo control group (35 patients); and test group (35 patients) | Negative control group (scaling), placebo control group (scaling plus placebo gel twice daily for a 4 week), and test group (scaling plus 0,2 % HA twice daily for a 4 week) | These clinical parameters, API, gingival index (GI), and PBI, were evaluated at intervals of 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks from baseline; microbiological parameters were monitored at the interval of 4 weeks from baseline | There is a significant difference for GI and PBI in the test group than the other groups. All treatment groups at 4 weeks showed a statistically significant reduction in percentage of anaerobic gram-negative bacilli and relative increase of gram-positive coccoid cells compared to baseline | ||

| Xu et al. | 20 patients (mean age 48.6 years) | Control sites are: molars and premolars of the first and third quadrants served. Test sites are molars and premolars of the second and fourth quadrants | The patients received SRP at baseline, and 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The patients applied in the test sites 1 mL 0.2% HA at baseline, and at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 | Sulcus fluid flow rate (SFFR) and sulcus bleeding index were evaluated at baseline and after 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 12 weeks; probing depth and clinical attachment level at baseline and 6 and 12 weeks. Dentists also took subgingival plaque samples, in order to determine the presence of Actinobacillus, actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythensis, and Treponema denticola, at baseline and 6 and 12 weeks | This study showed an improvement of all clinical variables in both groups. There are not clinical and microbiological differences between test and control sites | |

| Johannsen et al. | 11 patients; age range, 42–63 years | Contralateral pairs of premolar and canine teeth in the maxilla or the mandible were randomized to receive the test treatment (adjunctive HA gel) or to serve as SRP controls | The patients received SRP at baseline, and 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The patients applied in the test sites 1 mL 0.2% HA at baseline, and at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 | Sulcus fluid flow rate (SFFR) and sulcus bleeding index were evaluated at baseline and after 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 12 weeks; probing depth and clinical attachment level at baseline and 6 and 12 weeks. Dentists also took a subgingival plaque samples, in order to determine the presence of Actinobacillus, actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythensis, and Treponema denticola, at baseline and 6 and 12 weeks | This study showed an improvement of all clinical variables in both groups. There are not clinical and microbiological differences between test and control sites | |

| HA in gingivitis | ||||||

| Polepalle et al. | 30–60 years | In this split mouth study, 72 teeth (36 test sites and 36 control sites) in 18 patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis | Test sites received subgingival administration of 0.2 mL of 0.8% HA following SRP and 1 week later | Bleeding on probing (BOP), API, probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level (CAL) were assessed at baseline, 1, 4, and 12 weeks. Colony-forming units (CFU) per mL were assessed at baseline, after SRP, and after 2 weeks | There was a significant reduction in BOP, API, PPD, and CAL in the test sites than control group. In the test sites there was also a significant reduction of CFUs | |

| Gontiya et al. | Age range, 25–55 years | 26 patients with chronic periodontitis patients (120 sites selected). The sites were divided in two groups: control and experimental sites (HA gel) | The test sites received 1 mL of 0.2% HA gel at baseline and at the end of weeks 1, 2, and 3. Marginal gingival biopsy was obtained from experimental and control sites, providing tissue for histologic examinations | Clinical parameters GI, PBI, PPD, and Relative Attachment Level (RAL) evaluated at baseline (day 0), and weeks 4, 6, and 12 | The test sites showed statistically significant improvement in GI and PBI at 6 and 2 weeks than control sites | |

| Rajan et al. | HA group (33 sites) in 33 patients | The patients received SRP in the control and tests sites at baseline. In the test sites the patients applied 0.2% HA gel (Gengigel®) after SRP and 1 week post treatment | The clinical parameters evaluated: GI, API, BOP, PPD, CAL at three appointments: before SRP, 4 weeks and 12 weeks after SRP | In the HA group, this combined treatment showed a significant improvement in all clinical parameters: BOP, PPD, and CAL, at 12 weeks post therapy in comparison to the control group treated with SRP only | ||

| Pilloni et al. | Mean age 41.9 ± 15.1 years | 19 adult patients with mild chronic periodontitis and shallow pockets in two different quadrants (one quadrant with HA gel and the other quadrant without) | After SRP, daily and for 3 weeks, HA gel was applied in the test sites (one quadrant) with a toothbrush | These clinical parameters were evaluated before SRP and repeated at 14 and 21 days: API, BOP, PPD, GI, PAL (probing attachment level) | The treatment with HA gel showed a greater effect. BOP had a decrease of 92.7% and GI of 96.5%, whereas controls 75.8% and 79.0%, respectively. The difference of PPD in both areas was statistically significant in favor of the HA gel treated zone | |

| Eick et al. | 42 patients (18 men, 24 women; age range, 41–72 years). Only 34 completed the study | 17 patients | 17 patients | After the SRP, a gel containing 0.8% HA (1800 kDa) was introduced into all periodontal pockets in the HA group. In addition, the patients applied a gel containing 0.2% HA (1000 kDa) onto the gingival margin twice daily during the following 14 days. The control group was treated with SRP only; no placebo was used | Probing depth (PD) and CAL were recorded at baseline and after 3 and 6 months, and subgingival plaque and sulcus fluid samples were taken for microbiologic and biochemical analysis | PD and CAL were recorded at baseline and after 3 and 6 months, and subgingival plaque and sulcus fluid samples were taken for microbiologic and biochemical analysis |

| Chauhan et al. | 60 patients (30–65 years) | Group 1 (20 patients) SRP, Group 2 (20 patients) SRP + HA, Group 3 (20 patients) SRP + chlorhexidine (CHX) | In Group 1, the patients received only SRP treatment; in Groups 2 and 3, the patients, at least eight teeth, also received topical application of HA gel and CHX gel, respectively | Clinical parameters: GI, PPD, and CAL evaluated at baseline and 3 months, API evaluated at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months. Systemic/hematological parameters, blood samples for laboratory tests for total leucocyte count (TLC), differential leucocyte count (DLC), and C-reactive protein (CRP) evaluated at baseline, 24 h, and at 1 month and 3 months | At 3 months, change in PPD and CAL was more in Group 2 than Group 3, but the difference was non-significant | |

| Engström et al. | 15 patients No surgical group: nine patients (mean age, 48 years). Surgical group: six patients (mean age, 49 years) | In each of 15 individuals, two teeth were chosen. In the surgical group (six patients), a bioabsorbable membrane was used for both test and control sites, and HA was placed in the intrabony pocket of the test site. In the non-surgical group (nine patients), the periodontal pockets were scaled and HA was administered three times with an interval of 1 week in the test pockets | In the surgical group, full-thickness flap was elevated and the patients received SRP. In both the test and control sites, bone pockets, were covered with a matrix barrier based on bioabsorbable polyactic acid mixed with citric acid ster. In addition, HA was administered on test sites. In the no surgical group: Treatment including SRP of both test and control teeth. HA was administered in the test sites three times at 1-week intervals | Alveolar bone height and bone healing patterns, gingival crevicular fluid immunoglobulin (Igg, C3, and prostaglandin E2 [PGE2]) responses, PPD, BOP, and the presence of plaque evaluated at baseline before treatment, and at 2 weeks, and 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment | The observed difference in bone height between test and control sites in the surgical group after 12 months was less than 1 mm, which was only detectable on radiographs. A decrease in bone height was found for both groups after scaling. Probing depth reduction after the surgical treatment, as well as after scaling and root planing, was as expected | |

| HA in gingivitis | ||||||

| Briguglio et al. | Control group (42.3 ± 8.4 years), HA group (47.7 ± 8.1 years) | In this split mouth study, 72 teeth (36 test sites and 36 control sites) in 18 patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis | After the maintenance period, the patients were immediately planned for surgery. In the test group, the treated sites were filled with HA after the surgical access and cleaning phases were carried out. A similar procedure was performed for the control group, without the HA application | The following clinical parameters were recorded immediately prior to the surgery and repeated 12 and 24 months later: API, BOP, PD, and CAL | The treatment of infrabony defects with hyaluronic acid offered an additional benefit in terms of clinical attachment level gain, probing depth reduction, and predictability compared to treatment with open flap debridement | |

| Bevilacqua | Mean age, 51 ± 9.8 years | 11 patients with moderate-severe chronic periodontitis, who had four sites with pocket: 22 sites in the Control Group and 22 sites in the HA group | The patients in the HA group, received 0.5 mL of amino acids and HA gel (Aminogam Ò A) while the patients in the control group received 0.5 mL of placebo gel (Aminogam Ò B). Aminogam A and Aminogam B were applied in the test sites following the same procedure at | The clinical variables evaluated: API, BOP, CAL, PPD, Level calprotectin and myeloperoxidase (MPO), gingival crevicular fluid volume (GCF) at days 45 and 90. The quantity of calprotectin, MPO, and GCF was evaluated and recorded at test and control sites at 7 and 45 days | The HA group experienced at baseline at and 45 days a significant reduction in probing depth and bleeding on probing than control group. Also both groups had a significant reduction in μg/sample of calprotectin and myeloperoxidase after 1 week and an increase at 45 days | |

| Karim et al. | 14 patients with chronic periodontitis having four interproximal intrabony defects were included in this split-mouth study (for each patient, two sites in test group [HA gel] and two sites in control group [placebo] gel) | Test sites treated with modified Widman flap (MWF) surgery in conjunction with either 0.5 mL of 0.8% HA gel and control sites treated with the same procedure and placebo gel | BOP, API, PPD, and CAL were assessed at baseline, 1, 4, and 12 weeks. CFUs per mL were assessed at baseline, after SRP and after 2 weeks | There was a significant reduction in BOP, API, PPD, and CAL in the test sites than control group. In the test sites there was also a significant reduction of CFUs | ||

| HA in implant surgery and sinus lift | ||||||

| Araújo Nobre et al. | Mean age, 58.6 ± 9.51 years | 15 patients with HA gel | 15 patients with CHX gel | Thirty edentulous patients, with Brånemark System implants placed in the mandible, were randomly assigned to two groups (HA and CHX) | The clinical parameters evaluated: modified plaque index (mPlI), modified bleeding index (mBI), PPD in mL, suppuration (Sup), clinical implant mobility (mob). Both groups were followed up for 6 months, and the clinical observations were performed on day 10, and at 2, 4, and 6 months post surgery | HA and CHX showed good effects in maintaining a healthy peri-implant complex. Statistically significant differences were found in the HA group for modified bleeding index on the second observation. Modified plaque index and modified bleeding index revealed a potentially better result for CHX at 6 months |

| Vanden Bogaerde | Age range, 36–67 years | 19 defects were treated | Esterified HA in the form of fibers was packed into the periodontal defects | The PPDs, gingival recession, and CAL were evaluated before treatment and after 1 year | After 1 year there were these following result: PPD reduction, gingival recession increase, and CAL gain | |

| Ballini et al. | Mean age of 43.8 years for women, 40.0 years for men, and 42 years for all groups | 19 defects were treated. Nine patients with periodontal defects treated by an esterified low-molecular HA preparation (EHA) and autologous grafting | 0.5 cc of autologous bone blended with two bundles of EHA fibers and a few drops of physiological solution was positioned in the site. Finally, the flap was re-positioned and sutured with single stitches. After surgery, patients rinsed their mouths twice daily with 10 mL of 0.2 % CHX for 6 weeks | The clinical parameters evaluated: FMPS (full mouth plaque surfaces), FMBS (full mouth plaque surfaces), PPD (periodontal pocket depth), R: gingival recession, the cement enamel junction (CEJ), CAL, IBPD (intrabony pocket depth). Data were obtained at baseline before treatment and after 10 days, and at 6, 9, and 24 months after treatment | Clinical results showed a mean gain of CAL (gCAL) of 2.6 mm of the treated sites, confirmed by radiographic evaluation | |

| Koray et al. | 34 patients (15 men, 19 women; mean age, 23.35 ± 3.89 years) | 34 patients with bilateral symmetrically impacted mandibular third molars divided in the BnzHCl group and the HA group | All patients underwent two surgical operations: in the first operation, the right third molar was extracted while in the second operation, the left third molar was extracted. After both operations, the group applied the two pumps to the extraction area three times a day, for 7 days (BnzHCl spray or HA spray) | Swelling was evaluated using a tape measure method, pain with a visual analogue scale (VAS), and trismus by measuring the maximum inter-incisal opening. Assessments were made on the day of surgery and on days 2 and 7 after surgery | The patients with HA spray experienced statistically significant results for the swelling and trismus values than those with the BnzHCl spray | |

| HA in gingivitis | ||||||

| Romeo et al. | 45.5 years | HA group: 31 patients | Control group: 18 patients | In both groups, excisional biopsy was performed in oral soft tissues. In the HA group, the patients received HA gel after laser surgery; in the control group, the patients received no treatment involving a drug or gel | Numeric rating scale (NRS) was used to evaluate pain experienced after surgery (pain index [PI]). The lesion area was measured after surgery (T0) and after 7 days (T1). A percentage healing index (PHI) was calculated indicating healing extension in 7 days | HA cases showed an average PHI of 26.50–64.38%, whereas the average PHI in the CG was 27.84–47.88%. Mean PI was 0.96–2.67 for HA and 0.86–2.75 for CG. A statistically significant difference was detected between the groups for PHI, whereas no difference was detectable for PI |

| Kumar et al. | This was a randomized clinical trial with split-mouth design, where 10 patients with 20 sites of Millers Class I recession were treated and followed up for a period of 6 months | HA sites were treated with HA gel 0.2% with coronally advanced flap (CAF) while control sites were treated with CAF alone | Recession depth (RD) was measured regularly at baseline and 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 weeks postoperatively. PPD and CAL were also measured along with RD at baseline and 12 and 24 weeks | There was a significant change in RD, PPD, CAL, and percentage of root coverage in both groups when compared to the baseline values. There was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control sites in terms of RD, PPD, and CAL. Though there is no statistically significant difference root coverage in the experimental group, it appeared to be clinically more stable compared with the control group after 24 weeks | ||

| HA in oral ulcers | ||||||

| Lee et al. | 40 years | 33 patients :17 patients with Behcet’s disease, and 16 patients with recurrent aphthous ulcerations | Patients were treated with HA 0.2% gel twice a day for 2 weeks | Subjective assessment: number of ulcers, healing period and VAS; Objective assessment: number and maximal size of ulcer | A subjective reduction in the number of ulcers was reported by 72.7% of patients. A decrease in the ulcer healing period was reported by 72.7% of patients; 75.8% of patients experienced improvement in VAS for pain. Objective inspection of the ulcers showed a reduction of numbers in 57.6% of patients, and 78.8% of the ulcers showed a decrease in area. Among the inflammatory signs, swelling and local heat were significantly improved after treatment | |

| Nolan et al. | HA group (37 years); Control group (36 years) | HA group: 60 patients | Control group: 56 patients | Patients in the HA group were treated with HA gel 0.2% while patients in the control group with placebo (2–3 times per day for the next 7 days) | Mean number of ulcers; ulcer history during 7-day investigation period; number of patients with ulcer occurrence during 7-day investigation period; distribution of scores from patients’ overall assessment of their treatment (very good, good, moderate, poor, very poor, not recorded) | Patients in both groups reported a rapid reduction in their discomfort scores arising for their ulcers. This level of reduction was sustained for both treatment groups for about 30 min. Thereafter scores started to return to baseline. There was a slight decline in the number of ulcers, irrespective of treatments over the 7 day. On day 5, patients in the HA group had significantly fewer ulcers than those treated with placebo. In both treatment groups, new ulcers occurred throughout the investigation period but on day 4 the incidence of new ulcer occurrence was significantly lower in the HA group |

HA in gingivitis

Nowadays HA is a useful adjuvant treatment in gingivitis therapy.

Jentsch et al.21 showed that topical treatment with 0.2% HA twice daily for a 3-week period had a beneficial effect in the patients affected by gingivitis, improving the plaque indices, papillary bleeding index (PBI), and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) variables.

Pistorius et al.22 revealed that the topical application of a spray containing HA (5 times daily for 1 week) led to a reduction in the sulcus bleeding index (SBI), PBI values, and the GCF.

Similarly, Sahayata et al.23 observed that local application of 0.2% HA gel on inflamed gingiva, twice daily for a 4-week period, in addition to scaling and routine oral hygiene, provided a significant improvement in the gingival index (GI) and PBI when compared with both the placebo control group (scaling plus placebo gel) and negative control group (scaling only).

HA in chronic periodontitis

The local use of HA gel, twice a day for 1 month, in patients with chronic periodontitis, reduced the proliferation index of the gingival epithelium (expression of Ki-67 antigen), the inflammatory process and improved periodontal lesions.24

However, several studies suggested that a combined treatment composed of full-mouth scaling and root planing (SRP) and the topical administration of HA had a beneficial effect on periodontal health in chronic periodontitis.

Subgingival administration of 1 mL 0.2 mL 0.8% HA gel once a week for 6 weeks ameliorated the sulcus fluid flow rate (SFFR);25 Johannsen et al.26 noted two subgingival administrations of 0.2 mL 0.8% HA gel (at baseline and after 1 week) significantly reduced bleeding in the HA group when compared with the control group.

Similarly, Polepalle et al.27, showed that subgingival placement of 0.2 mL 0.8% HA gel premolars and canine teeth, following SRP, for 1 week, led to a significant reduction in bleeding on probing (BOP), plaque index, bleeding on probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment level (CAL), and colony-forming units (CFUs) compared with the control site treated with SRP only.

Gontiya et al.28 using the same treatment as Polepalle, Xu, and Johannsen, showed that the subgingival application of 0.2% hyaluronic acid gel (GENGIGEL®) with SRP in chronic periodontitis patients improved the GI and bleeding index (BI) when compared with control sites, as confirmed by a gingival biopsy, which showed a significant reduction of inflammatory infiltrate.

Rajan et al.29 showed that HA applied immediately after SRP and 1 week post therapy, has a beneficial effect on periodontal health in patients with chronic periodontitis. In the HA group, this combined treatment showed a significant improvement in all clinical parameters: BOP, PPD, and CAL, at 12 weeks post therapy in comparison to the control group treated with SRP only.

HA gel applied topically after SRP by massaging the gingiva with a soft bristled toothbrush for 3 weeks reduced the gingival inflammation improving all clinical parameters: PLI (plaque index), BOP, PPD, GI, and probing attachment level (PAL), compared with patients treated using normal oral hygiene procedures.30

Eick et al.31 evaluated the effect of the association of topical HA with different molecular weights. Immediately after the SRP, a gel containing 0.8% HA (1800 kDa) was introduced into all periodontal pockets; in addition, the patients applied a gel containing 0.2% HA (1000 kDa) onto the gingival margin twice daily for the following 14 days; in comparison with the control group (SRP only), the HA group showed a positive effect on PPD reduction and the prevention of recolonization by periodontopathogens (such as Campylobacter, Prevotella intermedia, and Porphyromonas gingivalis).

Chauhan et al.,32 in their clinical trials, enrolled 60 patients, randomly divided into three groups: the patients in group 1 received complete SRP and subgingival debridement, while the patients in groups 2 and 3, received topically applied HA gel and chlorhexidine (CHX) gel, respectively, after SRP procedure.

In all the three groups, a significant reduction in PPD and gain in CAL were observed between baseline and 3-month follow-up; however, at 3 months, the change in PPD and CAL was more in group 2 than group 3, but the difference was non-significant.

Engström et al.33 investigated in their study the anti-inflammatory effect and the effect on bone regeneration of HA in surgical and non-surgical groups in the patients with chronic periodontitis.

In the surgical group, a bioabsorbable membrane was used for both test and control sites, and HA was placed in the infrabony pocket of the test site.

In the non-surgical group, the periodontal pockets were scaled and HA was administered three times with an interval of 1 week in the test pockets.

They observed difference in bone height between test and control sites in the surgical group after 12 months, less than 1 mm, which was only detectable on radiographs. No statistical difference was found on radiographs in the non-surgical group, where a decrease in bone height was found for both groups after scaling.

PPD reduction after the surgical treatment, as well as after SRP, was as expected. They showed that HA in contact with bone and soft tissues had no influence on the immune system in this study.

HA has also been used in conjunction with open flap debridement (OFD) for the treatment of infrabony defects, offering an additional benefit in terms of CAL gain, PPD reduction, and predictability compared to patients with chronic periodontitis who underwent OFD treatment alone.34

Bevilacqua et al.35 proved that the subgingival application of 0.5 mL of amino acids and HA gel following ultrasonic mechanical instrumentation is beneficial for improving periodontal parameters in patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis in comparison to patients treated with only ultrasonic debridement. This combined treatment reduced PPD and BOP.

The topical application of 0.8% HA gel in addition to modified Widman flap (MWF) surgery improved the CAL and gingival recession (GR) more than MWF surgery alone or the application of a placebo gel, as indicated in the study carried out by Karim et al.36

The use of HA in implant surgery and sinus lift

Araújo Nobre et al.37 compared the health status of the peri-implant complex during the healing period of immediate function implants, using HA or CHX gels. They found a statistically significant lower modified bleeding index in the HA group in comparison with the control group treated with CHX. It might be advantageous to purpose combined treatment using HA 0.2% gel in the first 2 months and 0.2% CHX from months 2 to 6.

Vanden Bogaerde et al.38 investigated the clinical efficacy of treating deep periodontal defects using esterified HA in packed fibers in the defect. One year after treatment, the mean PPD was reduced, GR has increased, and attachment gain was recorded.

Ballini et al.39 suggested that autologous bone combined with an esterified low-molecular HA preparation seems to have good capabilities in accelerating new bone formation in infrabony defects.

The topical administration of a 0.2% HA spray three times a day, for 7 days following impacted third molar surgery to the extraction area, appears to offer a beneficial effect in the management of swelling and trismus during the immediate postoperative period when compared with the topical administration of 0.15% benzydamine hydrochloride spray.40

Romeo et al.41 showed that the use of a gel containing amino acids and 1.33% HA, topically applied three times per day for 1 week, can promote faster secondary intention healing in laser-induced wounds in patients who underwent an excisional biopsy of the oral soft tissues than the rate of healing the control group. It could considerably quicken the repair processes although it does not seem to affect pain perception.

In contrast to the above mentioned authors, Galli et al.,42 conducted a study using a Likert scale 10 days postoperatively and found that a single application of 0.8% HA does not appear to improve wound healing when applied to the surgical incisions in the oral cavity.

Finally, Kumar et al.43 evaluated the efficacy of HA gel in root coverage procedures as an adjunct to coronally advanced flap (CAF) procedure.

In this split mouth study design, 10 patients with 20 sites of Millers Class I recession were treated and followed-up for a period of 6 months.

Experimental sites were treated with HA gel 0.2% and CAF while control sites were treated with CAF alone.

There was a significant change in RD, PPD, CAL, and percentage of root coverage in both groups when compared to the baseline values, but there was no statistically significant difference between HA sites and control sites in terms of RD, PPD and CAL.

Though there is no statistically significant difference, root coverage in the HA sites appeared to be clinically more stable than the control site treated with CAF alone after 24 weeks.

HA in oral ulcers

Several studies focused their attention on use of HA as topical treatment for oral ulcers.

In particular Nolan44 showed that topical application of 0.2% HA gel twice daily for 2 weeks seems to be an effective and safe therapy in patients with recurrent aphthous ulcers (RAU).

Lee et al.45 investigated the efficacy of the topical application of 0.2% HA gel for oral ulcers in patients with RAU and the oral ulcers of Behçet’s disease (BD). In this study, HA gel application improved subjective parameters (number of ulcers, healing period, visual analogue scale [VAS] for pain), and objective parameters (number of ulcers, maximal area of ulcer, and inflammatory signs such as swelling and local heat).

Discussion

Hyaluronan is a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan found in the extracellular matrix of all vertebrate tissues, which plays a multifunctional role in scar-free wound healing, while also paramount role in physiology in the oral cavity and in the field of dentistry. The data, which have emerged from our analysis of the literature, allow us to suggest that hyaluronan may play a potential role in periodontal tissue healing and as an aid to the treatment of periodontal disease.

HA promotes a remission of symptoms, not only in the marginal gingiva, but also in the deeper-seated periodontal tissues, via the known mechanisms established for hyaluronan in wound healing.

Topical HA can be useful as a coadjutant treatment in gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, as well as during the postoperative period both for implant and sinus lift procedures for faster healing and to reduce the patients’ discomfort during the postoperative period. Finally, topical HA may be a valuable treatment for oral ulcers.

We would like to emphasize that topical treatments are more effective in their ability to deliver high concentrations of pharmacological agents to the teeth and oral mucosa, rather than systemic administration.

Further laboratory-based research and large-scale randomized controlled clinical trials imply that HA may be a suitable carrier of cells from periodontal tissue, promoting tissue regeneration in the augmentation of both mineralized and non-mineralized periodontal tissue.

More studies are necessary to identify the best way of administration (spray, gel, nebulization, and so on) in addition to the best method of scheduling postoperative treatment for each dental condition.

Conclusion

Today HA is widely used in many branches of medicine with interesting potential applications in dentistry for the treatment of acute and chronic inflammatory disease.

Data obtained from the present review of 20 clinical studies demonstrate that, due to its positive action on tissue repair and wound healing, topical administration of HA could play a role not only in postoperative dental surgery, but also in the treatment of patients affected by gingivitis and periodontitis, with a significant improvement in their quality of life. Further laboratory-based research and large-scale randomized controlled clinical trials on a larger scale are advisable to confirm these promising results.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1. Ialenti A, Di Rosa M. (1994) Hyaluronic acid modulates acute and chronic inflammation. Agents and Actions 43: 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dahiya P, Kamal R. (2013) Hyaluronic acid: A boon in periodontal therapy. North American Journal of Medical Science 5: 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ijuin C, Ohno S, Tanimoto K, et al. (2001) Regulation of hyaluronan synthase gene expression in human periodontal ligament cells by tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta and interferon-gamma. Archives of Oral Biology 46: 767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartold PM, Page RC. (1986) The effect of chronic inflammation on gingival connective tissue proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid. Journal of Oral Pathology 15: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waddington RJ, Moseley R, Embery G. (2000) Reactive oxygen species: A potential role in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. Oral Diseases 6: 138–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manzanares D, Monzon ME, Savani RC, et al. (2007) Apical oxidative hyaluronan degradation stimulates airway ciliary beating via RHAMM and RON. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 37: 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamalik N, Kilinc K, Caglayan F, et al. (1998) Molecular size distribution analysis of human gingival proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans in specific periodontal diseases. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 25: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tipler LS, Embery G. (1985) Glycosaminoglycan-depolymerizing enzymes produced by anaerobic bacteria isolated from the human mouth. Archives of Oral Biology 30: 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laurent TC. (1998) The Chemistry, Biology and Medical Applications of Hyaluronan and its Derivatives. London: Portland Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sutherland IW. (1998) Novel and established applications of microbial polysaccharides. Trends in Biotechnology 16: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen WY, Abatangelo G. (1999) Functions of hyaluronan in wound repair. Wound Repair and Regeneration 7: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bertolami CN, Messadi DV. (1994) The role of proteoglycans in hard and soft tissue repair. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine 5: 311–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hakkinen L, Uitto VJ, Larjava H. (2000) Cell biology of gingival wound healing. Periodontology 2000 24: 127–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Migliore A, Granata M. (2008) Intra-articular use of hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Clinical Interventions in Aging 3: 365–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. (2013) Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid and other drugs in the knee joint. HSS Journal 9: 180–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allegra L, Della Patrona S, Petrigni G. (2012) Hyaluronic acid: Perspectives in lung diseases. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 207: 385–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weindl G, Schaller M, Schafer-Korting M, et al. (2004) Hyaluronic acid in the treatment and prevention of skin diseases: Molecular biological, pharmaceutical and clinical aspects. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology 17: 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casale M, Moffa A, Sabatino L, et al. (2015) Hyaluronic acid: Perspectives in upper aero-digestive tract. A systematic review. PLoS One 10: e0130637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mendes RM, Silva GA, Lima MF, et al. (2008) Sodium hyaluronate accelerates the healing process in tooth sockets of rats. Archives of Oral Biology 53: 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bertl K, Bruckmann C, Isberg PE, et al. (2015) Hyaluronan in non-surgical and surgical periodontal therapy: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 42: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jentsch H, Pomowski R, Kundt G, et al. Treatment of gingivitis with hyaluronan. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 30: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pistorius A, Martin M, Willershausen B, et al. (2005) The clinical application of hyaluronic acid in gingivitis therapy. Quintessence International 36: 531–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sahayata VN, Bhavsar NV, Brahmbhatt NA. (2014) An evaluation of 0.2% hyaluronic acid gel (Gengigel (R)) in the treatment of gingivitis: A clinical & microbiological study. Oral Health and Dental Management 13: 779–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mesa FL, Aneiros J, Cabrera A, et al. (2002) Antiproliferative effect of topic hyaluronic acid gel. Study in gingival biopsies of patients with periodontal disease. Histology and Histopathology 17: 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu Y, Hofling K, Fimmers R, et al. (2004) Clinical and microbiological effects of topical subgingival application of hyaluronic acid gel adjunctive to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology 75: 1114–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johannsen A, Tellefsen M, Wikesjo U, et al. (2009) Local delivery of hyaluronan as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology 80: 1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polepalle T, Srinivas M, Swamy N, et al. (2015) Local delivery of hyaluronan 0.8% as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiological study. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 19: 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gontiya G, Galgali SR. (2012) Effect of hyaluronan on periodontitis: A clinical and histological study. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 16: 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajan P, Baramappa R, Rao NM, et al. (2014) Hyaluronic acid as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis. A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 8: ZC11–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pilloni A, Annibali S, Dominici F, et al. (2011) Evaluation of the efficacy of an hyaluronic acid-based biogel on periodontal clinical parameters. A randomized-controlled clinical pilot study. Annali di Stomatologia 2: 3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eick S, Renatus A, Heinicke M, et al. (2013) Hyaluronic acid as an adjunct after scaling and root planing: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology 84: 941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chauhan AS, Bains VK, Gupta V, et al. (2013) Comparative analysis of hyaluronan gel and xanthan-based chlorhexidine gel, as adjunct to scaling and root planing with scaling and root planing alone in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A preliminary study. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry 4: 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Engstrom PE, Shi XQ, Tronje G, et al. (2001) The effect of hyaluronan on bone and soft tissue and immune response in wound healing. Journal of Periodontology 72: 1192–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Briguglio F, Briguglio E, Briguglio R, et al. (2013) Treatment of infrabony periodontal defects using a resorbable biopolymer of hyaluronic acid: A randomized clinical trial. Quintessence International 44: 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bevilacqua L, Eriani J, Serroni I, et al. (2012) Effectiveness of adjunctive subgingival administration of amino acids and sodium hyaluronate gel on clinical and immunological parameters in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Annali di Stomatologgia 3: 75–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Dahaba MA, Aboul-Ela S, et al. Local application of hyaluronan gel in conjunction with periodontal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Oral Investigations 16: 1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Araujo Nobre M, Cintra N, Malo P. (2007) Peri-implant maintenance of immediate function implants: A pilot study comparing hyaluronic acid and chlorhexidine. International Journal of Dental Hygiene 5: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vanden Bogaerde L. (2009) Treatment of infrabony periodontal defects with esterified hyaluronic acid: Clinical report of 19 consecutive lesions. International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry 29: 315–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ballini A, Cantore S, Capodiferro S, et al. (2009) Esterified hyaluronic acid and autologous bone in the surgical correction of the infra-bone defects. International Journal of Medical Science 6: 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koray M, Ofluoglu D, Onal EA, et al. (2014) Efficacy of hyaluronic acid spray on swelling, pain, and trismus after surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 43: 1399–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Romeo U, Libotte F, Palaia G, et al. (2014) Oral soft tissue wound healing after laser surgery with or without a pool of amino acids and sodium hyaluronate: A randomized clinical study. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery 32: 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Galli F, Zuffetti F, Capelli M, et al. (2008) Hyaluronic acid to improve healing of surgical incisions in the oral cavity: A pilot multicentre placebo-controlled randomised clinical trial. European Journal of Oral Implantology 1: 199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kumar R, Srinivas M, Pai J, et al. (2014) Efficacy of hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan) in root coverage procedures as an adjunct to coronally advanced flap in Millers Class I recession: A clinical study. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 18: 746–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nolan A, Baillie C, Badminton J, et al. (2006) The efficacy of topical hyaluronic acid in the management of recurrent aphthous ulceration. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 35: 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee JH, Jung JY, Bang D. (2008) The efficacy of topical 0.2% hyaluronic acid gel on recurrent oral ulcers: Comparison between recurrent aphthous ulcers and the oral ulcers of Behcet’s disease. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 22: 590–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]