Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization recommends that human growth should be monitored with the use of international standards. However, in obstetric practice, we continue to monitor fetal growth using numerous local charts or equations that are based on different populations for each body structure. Consistent with World Health Organization recommendations, the INTERGROWTH-21st Project has produced the first set of international standards to date pregnancies; to monitor fetal growth, estimated fetal weight, Doppler measures, and brain structures; to measure uterine growth, maternal nutrition, newborn infant size, and body composition; and to assess the postnatal growth of preterm babies. All these standards are based on the same healthy pregnancy cohort. Recognizing the importance of demonstrating that, postnatally, this cohort still adhered to the World Health Organization prescriptive approach, we followed their growth and development to the key milestone of 2 years of age.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the babies in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project maintained optimal growth and development in childhood.

Study Design

In the Infant Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project, we evaluated postnatal growth, nutrition, morbidity, and motor development up to 2 years of age in the children who contributed data to the construction of the international fetal growth, newborn infant size and body composition at birth, and preterm postnatal growth standards. Clinical care, feeding practices, anthropometric measures, and assessment of morbidity were standardized across study sites and documented at 1 and 2 years of age. Weight, length, and head circumference age- and sex-specific z-scores and percentiles and motor development milestones were estimated with the use of the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards and World Health Organization milestone distributions, respectively. For the preterm infants, corrected age was used. Variance components analysis was used to estimate the percentage variability among individuals within a study site compared with that among study sites.

Results

There were 3711 eligible singleton live births; 3042 children (82%) were evaluated at 2 years of age. There were no substantive differences between the included group and the lost-to-follow up group. Infant mortality rate was 3 per 1000; neonatal mortality rate was 1.6 per 1000. At the 2-year visit, the children included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards were at the 49th percentile for length, 50th percentile for head circumference, and 58th percentile for weight of the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards. Similar results were seen for the preterm subgroup that was included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards. The cohort overlapped between the 3rd and 97th percentiles of the World Health Organization motor development milestones. We estimated that the variance among study sites explains only 5.5% of the total variability in the length of the children between birth and 2 years of age, although the variance among individuals within a study site explains 42.9% (ie, 8 times the amount explained by the variation among sites). An increase of 8.9 cm in adult height over mean parental height is estimated to occur in the cohort from low-middle income countries, provided that children continue to have adequate health, environmental, and nutritional conditions.

Conclusion

The cohort enrolled in the INTERGROWTH-21st standards remained healthy with adequate growth and motor development up to 2 years of age, which supports its appropriateness for the construction of international fetal and preterm postnatal growth standards.

Key words: development, INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards, postnatal growth

Although human growth, from cell to whole body, is recognized as a universal biologic process, some entrenched views persist regarding fetal growth, in particular that it should be compared with a site-specific rather than prescriptive population. This view is not held by the World Health Organization (WHO) or by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention,1, 2 which recommend using international neonatal standards. Likewise, such standards have now been adopted to estimate the burden and consequences of babies being born small for gestational age in low- and middle-income countries.3

We have summarized the key statistical, physiologic, ethnic, and genetic evidence relating to this issue.4, 5 Practically, the debate focuses on whether it is correct to monitor fetal growth using 1 of the many site-specific charts available. Typically, such charts are based on different populations for each fetal body structure and have been developed at hospital level.4 These multiple, site-specific charts are references, not international standards that are used commonly in most other areas of biology and medicine.

This neglected aspect of obstetric practice means that clinical decisions are made based on reference charts that were derived from a wide range of different study populations. For example, a woman may have an early gestational age assessment with the use of a fetal crown-rump length chart based on a study of 80 women from Glasgow, Scotland,6, 7 followed by a clinical assessment with the use of a fundal height chart based on 313 women from Cardiff, Wales.8 Fetal biometry values may then be compared with 1 of many local charts,9 and, during the same ultrasound scan, estimated fetal weight may be determined from an equation based on 109 fetuses studied in Texas during the 1980s,10, 11 complemented by a recent chart from other US populations.12

If the woman requires further assessment, the umbilical Doppler measures are judged with the use of yet another reference population.13 At birth, the anthropometric measures of the newborn infant could be evaluated with the use of a multiplicity of reference charts, all of which are totally unrelated to the fetal growth charts that were being used just a few weeks earlier.

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project aimed to resolve these issues by conducting studies of human growth and development that involved pregnant women who were enrolled at <14 weeks gestation specifically to monitor their fetuses, newborn infants, and children prospectively up to 2 years of age to generate a single set of international standards to make judgements on the growth of all humans.14 The studies were based conceptually on the WHO prescriptive approach to constructing human growth standards.15 The study populations across geographically delimited areas were selected because they had the recommended health, nutrition, and socioeconomic status that was required to construct international standards.15

Hence, the INTERGROWTH-21st Standards (from maternal weight gain, to pregnancy dating, fetal growth and estimated fetal weight, to brain structures, amniotic fluid volume, umbilical artery Doppler measures, and newborn body composition) are prescriptive because they are based on a cohort of “healthy” pregnancies and babies from the same geographically selected populations in which most of the health and nutritional needs of mothers were met and adequate antenatal care provided.

Nevertheless, the question always remains with studies that are focused on fetal growth as to how “healthy” were these children after birth and during childhood (ie, are they truly healthy?). We took this question seriously very early in the planning of the project and added a clinical and developmental follow-up evaluation16, 17, 18 beyond the customary early neonatal period as a further criterion to support the assertion that INTERGROWTH-21st babies represent true standard populations.19 The key milestone of 2 years of age was identified as a realistic and biologically relevant time point.20

Hence, we first compared the INTERGROWTH-21st Standards4, 21, 22 with the WHO Child Growth Standards.23 We demonstrated that, during the early neonatal period, the participants who were selected were appropriate and met the WHO prescriptive criteria for optimal growth.15 We then extended, for the first time in this literature, the prescriptive evaluation by designing the Infant Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.

This study aimed to evaluate the growth, nutrition, morbidity, and motor development at 2 years of age of the infants who were included in the international fetal and preterm growth standards to reinforce their prescriptive nature against which fetuses and preterm infants worldwide can now be compared.

Materials and Methods

INTERGROWTH-21st was a multicenter, population-based project that was conducted between 2009 and 2016 in 8 locations: Pelotas, Brazil; Turin, Italy; Muscat, Oman; Oxford, UK; Seattle, WA; Shunyi County, Beijing, China; the central area of Nagpur, India, and the Parklands suburb of Nairobi, Kenya.14, 24

The primary aim of the project was to study growth, health, nutrition, and neurodevelopment from <14 weeks gestation to 2 years of age.14 In the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project,21 we recruited women from these 8 populations who initiated antenatal care at <14 weeks gestation and who met the entry criteria of optimal health, nutrition, education, and socioeconomic status.14

Gestational age was estimated based on the date of the last menstrual period and corroborated by ultrasound measurement of crown-rump length at 9+0 to 13+6 weeks gestation with the use of a standard protocol. All fetuses in the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study were eligible to contribute data to the construction of the international fetal growth standards; all infants who were born at <37 weeks gestation in the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study were eligible to contribute data to the construction of the international Postnatal Growth Standards for Preterm Infants. At each postnatal visit, a record of any illnesses in the preceding months was noted in addition to anthropometric measurements and a developmental assessment.

Weight, length, and head circumference were obtained within 12 hours (and no >24 hours) of birth on the postnatal wards and at follow-up visits that were scheduled at 1 and 2 years of age (±1 month). Measurements were taken exclusively by the same teams who were trained and standardized at regular intervals for the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.25

All study sites used the same methods and equipment: electronic scales (Seca, Hangzhou, China) for weight (sensitivity of 10 g to 20 Kg); a specially designed Harpenden infantometer (Chasmors Ltd, London, UK) for recumbent length, and a metallic nonextendable tape (Chasmors Ltd) for head circumference.26, 27 Measurement procedures were standardized according to WHO recommendations.28 During the central standardization sessions for anthropometrists, the intra- and interobserver error of measurement values for recumbent length ranged from 0.3–0.6 cm and for head circumference from 0.2–0.5 cm.25

Measurements were taken twice, independently, by 2 of the study anthropometrists. If the difference between the 2 measures exceeded for weight 50 g for newborn infants and ≤100 g at 1 and 2 years of age (length, 7 mm; head circumference, 5 mm), then both observers independently repeated that measurement a second time and, if necessary, a third time.25, 27

When the Infant Follow-up Study started, some enrolled children had passed their second birthday already. The families of these children were invited to a follow-up visit with the maximum age at assessment for the child being 27 months. Similarly, those children who already had passed their first birthday, but were <2 years old, were invited initially for the first visit up to the age of 18 months. In total, only 14% of 1- and 2-year visits occurred outside the protocol-designated age range for assessment.

Detailed information was obtained from the mother about the infant’s health, severe morbidities, length of breastfeeding, timing of the introduction of food, feeding practices, and food intake with the use of standardized forms that were produced especially for the project (www.intergrowth21.org).

WHO protocols were followed to assess motor development milestones.29 We focused on 4 WHO milestones that are less likely to be affected by recall bias: sitting without support, hands and knees crawling, standing alone, and walking alone. Data were collected by trained staff using a form with pictures of the relevant child positions and corresponding definitions. Parents were asked to report the age in months and weeks when they first observed or “never observed” the milestones (http://www.intergrowth21.org.uk).

We collected the same information from parents at 1 and 2 years of age to evaluate the consistency of the reported dates. There were 7965 pairs of values recorded at year 1 and the year 2 interviews, of which 92.6% were identical at both visits. Among the 588 discrepant values, the median difference ranged between –1 week (interquartile range, −4.3–4.3) for hands and knees crawling to –0.2 weeks (interquartile range, –6.3–2.3) for standing alone. In these cases, after investigation, the values that were obtained at the 1-year visit were used.

Across all study sites, standardized clinical care and feeding practices were implemented based on protocols that were developed by the INTERGROWTH-21st Neonatal Group (http://www.intergrowth21.org.uk).30, 31, 32 Exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months was promoted for all babies, with supplementation for preterm infants as recommended.30, 33, 34

Age- and sex-specific z-scores and percentiles were estimated for each child at 2 years of age comparing their weight, length, and head circumference to the WHO Child Growth Standards.35 Corrected age was used for the preterm subgroup.36 Four values (3 for weight and 1 for head circumference) were above or below 5 standard deviations (SD) of the mean of the study population and were excluded.

Variance components analysis was performed to calculate the percentage of variance in infant length at birth, 1, and 2 years because of between- and within-site variance. A multilevel mixed effects model was fitted with random intercepts for the study site and individual levels (with individuals nested within sites). The model, which was fitted with unstructured covariance structure, was adjusted by age (after fractional polynomial transformation) and sex. Both age and sex were treated as fixed effects.

We analyzed 2026 mother-father-infant trios to compare the “mean parental height” with a predicted adult height for each infant, defined as twice their length at 2 years of age.37

For infants reported to have achieved the milestones, the proportions within the WHO motor development windows of achievement35 were estimated, and z-scores were calculated by subtraction of the median age of achievement reported in the WHO motor development study from the median age of achievement in our cohort, and division by the SD in the WHO motor development study. Corrected age was used for the preterm subgroup.

The proportion of infants who received breast milk and vitamin and mineral supplements and those who followed a special diet were estimated at 1 and 2 years of age.38, 39

We used Stata software (version 12; StataCorp, College Station, TX). Data were entered locally into the specially developed online data management system (http://medscinet.com).40

The INTERGROWTH-21st Project was approved by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee “C” (reference: 08/H0606/139), the research ethics committees of the individual institutions, and the regional health authorities where the project was implemented. Participants provided written consent to be involved in the study.

Results

Population characteristics

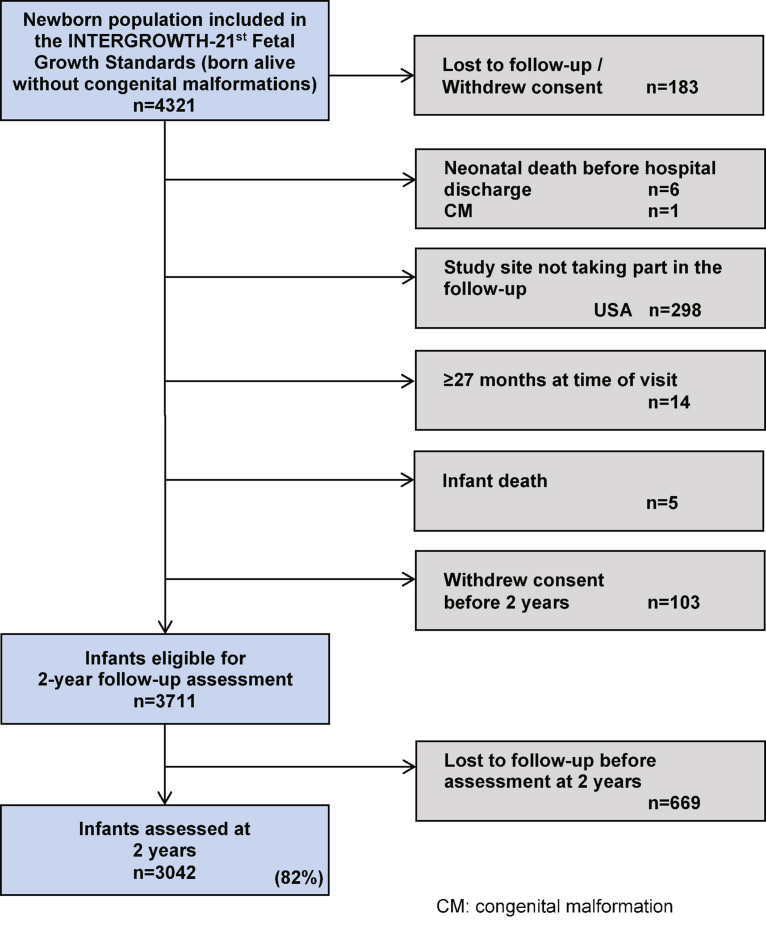

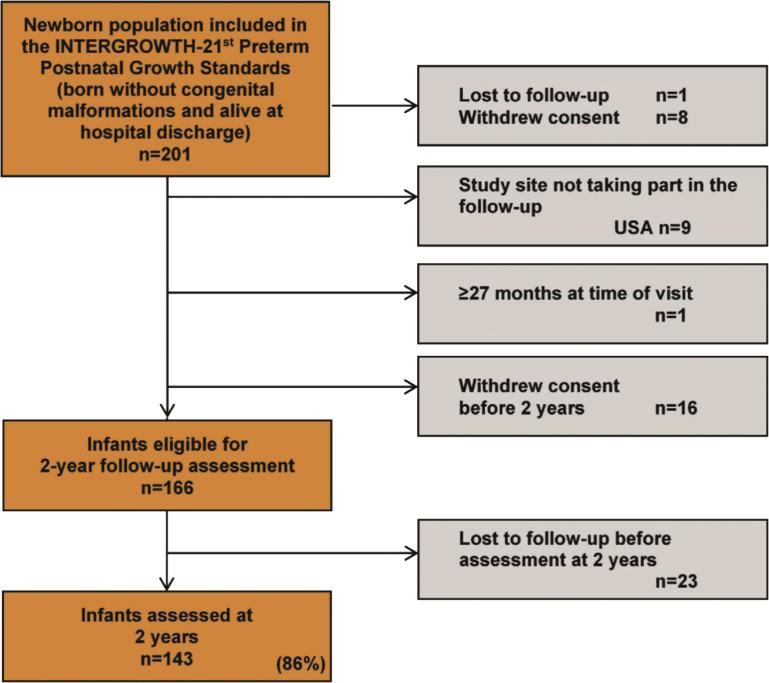

There were 4321 singleton newborn infants who were alive at birth without congenital malformations whose mothers were recruited at <14 weeks gestation and included in the cohort of the international INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards.21 Among these, 183 infants were lost to follow up or withdrew consent during pregnancy; 298 infants were ineligible for the Infant Follow-up Study because the study site in Seattle, WA, could not participate. There were 6 neonatal deaths before hospital discharge (neonatal mortality rate, 1.6/1000 live births), 1 congenital malformation that was detected after birth, and 5 infant deaths, which represented a total infant mortality rate of 3 per 1000 live births. In addition, 103 mothers withdrew consent early in the study. Finally, 14 infants were >27 months old at the time the follow-up started; they therefore were not invited to participate. Hence, 3711 newborn infants were eligible for the Infant Follow-up Study, of these, 669 infants were lost to follow up. Thus, the total cohort that was studied comprised 3042 infants (Figure 1) who represented 82% of those eligible (86% for the preterm subgroup, 143/166; Supplementary Figure).

Figure 1.

Study flow of the INTERGROWTH-21st Infant Follow-up Study

The chart indicates the cohort that contributed data to the construction of the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards.21

CM, congenital malformation; USA, United States of America.

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Supplementary Figure.

Study flow of INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Follow-up at 2 years

The chart shows the cohort that contributed data to the construction of the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards.22

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

The means (±SD) of the age at which measures were obtained were 24.4±1.2 and 23.2±0.7 months for the total cohort and the preterm subgroup, respectively; 86% of the 2-year measures were obtained from 23–25 months for the total cohort and 93% were obtained for the preterm subgroup.

The neonatal characteristics of the infants divided into those that completed the 2-year follow-up evaluations (n=3042) and those lost to follow up (n=669) are presented in Table 1. Both groups were similar in terms of anthropometric measures at birth and neonatal morbidity. A similar comparison within the preterm subgroup is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Neonatal characteristics of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 who were evaluated at 2 years of age compared with children who were lost to follow-up

| Characteristic | Evaluated at 2 years of age (n=3042) | Not evaluated at 2 years of agea (n=669) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery, wkb | 39.4±1.4 | 39.4±1.4 |

| Birthweight, kgb | 3.2±0.5 | 3.2±0.5 |

| Birth length, cmb | 49.1±2.0 | 49.2±2.0 |

| Head circumference, cmb | 33.7±1.4 | 33.9±1.3 |

| Apgar at 5 minb | 9.6±0.6 | 9.7±0.6 |

| Age at hospital discharge, dc | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Early preterm, <34 wk gestation, n (%) | 18 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) |

| Boys, n (%) | 1516 (49.8) | 324 (48.4) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit stay >1 d but <3 d, n (%) | 160 (5.3) | 35 (5.2) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia, n (%) | 137 (4.5) | 37 (5.5) |

| Respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 51 (1.7) | 15 (2.2) |

| Transient tachypnea of the newborn infant, n (%) | 65 (2.1) | 15 (2.2) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge, n (%) | 2698 (88.8) | 591 (88.5) |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Children lost to follow-up before evaluation at 2 years of age

Data are means±standard deviation

Data are given as median (interquartile range).

Table 2.

Neonatal characteristics of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 who were evaluated at 2 years of age compared with children lost to follow-up

| Characteristic | Evaluated at 2 years of age (n=143) | Not evaluated at 2 years of agea (n=24) |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery, wkb | 35.5±1.6 | 35.7±1.4 |

| Birthweight, kgb | 2.5±0.5 | 2.4±0.5 |

| Birth length, cmb | 45.7±2.7 | 45.6±2.3 |

| Head circumference, cmb | 31.8±1.7 | 31.8±1.5 |

| Apgar at 5 minb | 9.2±0.9 | 9.2±1.2 |

| Age at hospital discharge, dc | 4 (2–9) | 4 (2–7) |

| Early preterm, <34 weeks gestation, n (%) | 19 (13.3) | 3 (12.5) |

| Boys, n (%) | 73 (51.0) | 8 (33.3) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit stay >1 but <3 d, n (%) | 59 (41.3) | 11 (45.8) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia, n (%) | 29 (20.3) | 3 (12.5) |

| Respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 20 (14.0) | 6 (25.0) |

| Transient tachypnea of the newborn infant, n (%) | 23 (16.1) | 1 (4.2) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge, n (%) | 106 (74.1) | 19 (79.2) |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Children lost to follow-up before evaluation at 2 years of age

Data are given as mean±standard deviation

Data are given as median (interquartile range).

Feeding practices

At hospital discharge, 89% of the total cohort and 74% of the preterm subgroup were exclusively breast-milk fed. Similar patterns were seen among the children who were lost to follow-up at 2 years of age. Exclusive breastfeeding was stopped at a median of 5 months (interquartile range, 3–6 months); this was similar in the preterm subgroup. Breastfeeding stopped entirely at a median of 12 months (interquartile range, 6–18 months) for the total cohort and 11 months (interquartile range, 5–18 months) for the preterm subgroup.

In the total cohort, the proportion of children who still were receiving breast milk fell from 59% at 1 year to 11% at 2 years, by which time 34% of the children were formula fed. All children received dairy products of some type (including human milk) at both ages. Food supplements had been given routinely to 33% of children by 1 year and 21% by 2 years. At 1 year of age, 51% of the infants in the preterm subgroup were still receiving breast milk; the figure fell to 8% at 2 years, by which time 34% of children were receiving formula. Food supplements that included vitamins and minerals were given to 36% of the infants in the first year and 28% of the infants by the second year in the preterm cohort. Complementary feeding practices were considered appropriate in terms of diversity, the timing of introduction, and the food variety across sites (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).34

Postnatal morbidity

The overall morbidity rate in the total cohort was low (Table 3); only 9% of infants were hospitalized (median length of stay, 3 days) in the second year of life. The most frequently reported or diagnosed conditions were acute respiratory infections, diarrhea, and/or gastrointestinal problems with few repeated episodes, skin problems, and febrile episodes. Antibiotics were prescribed on >3 occasions in 10.9% and 15.8% of children in the first and second years, respectively, which corresponds closely to the rate of reported fever episodes (Table 3). Similar patterns were seen in the preterm subgroup (Table 4). Most of the infants were fully vaccinated in accordance with recommended policies.

Table 3.

Morbidity in the previous year of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 at 1 and 2 years of age

| Medical condition | 1 Year of age (n=2834), n (%) | 2 Years of age (n=3042), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized at least once | 344 (12.1) | 272 (8.9) |

| Total no. of days hospitalized | 3 (1–5)a | 3 (1–5)a |

| Any prescription made by a healthcare professional | 1783 (62.9) | 1911 (62.9) |

| Antibiotics (≥3 regimens) | 308 (10.9) | 481 (15.8) |

| Iron/folic acid/vitamin B12/other vitamins | 815 (28.8) | 430 (14.1) |

| Up-to-date with local vaccination policies | 2607 (92.0) | 2903 (95.4) |

| Otitis media/pneumonia/bronchiolitis | 228 (8.0) | 293 (9.6) |

| Parasitosis/diarrhea/vomiting | 148 (5.2) | 139 (4.6) |

| Seizures/cerebral palsy/neurologic disorders | 9 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) |

| Exanthema/skin disease | 456 (16.1) | 399 (13.1) |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | 4 (0.1) | 10 (0.3) |

| Fever ≥3 d (≥3 episodes) | 293 (10.3) | 309 (10.2) |

| Malaria | 13 (0.5) | 12 (0.4) |

| Meningitis | 5 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other infections that required antibiotics | 69 (2.4) | 79 (2.6) |

| Hearing problems | 4 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| Asthma | 24 (0.8) | 42 (1.4) |

| Cardiovascular problems | 9 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) |

| Blindness | 6 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 88 (3.1) | 9 (0.3) |

| Any hemolytic condition | 14 (0.5) | 22 (0.7) |

| Any malignancy | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) |

| Cow’s milk protein allergy | NA | 21 (0.7) |

| Food allergies | NA | 52 (1.7) |

| Injury trauma | 43 (1.5) | 130 (4.3) |

| Any condition that required surgery | 31 (1.1) | 34 (1.1) |

NA, not applicable (data were not collected at the 1-year follow-up visit); UTI, urinary tract infection.

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Data are given as median (interquartile range).

Table 4.

Morbidity of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 at 1 and 2 years of age

| Medical condition | 1 Year of age (n=154), n (%) | 2 Years of age (n=143), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized at least once | 34 (22.1) | 7 (4.9) |

| Total number of days hospitalized | 5 (3–8)a | 7 (3–9)a |

| Any prescription made by a healthcare professional | 98 (63.6) | 72 (50.3) |

| Antibiotics (≥3 regimens) | 31 (20.1) | 12 (8.4) |

| Iron/folic acid/vitamin B12/other vitamins | 56 (36.4) | 23 (16.1) |

| Up-to-date with local vaccination policies | 139 (90.3) | 136 (95.1) |

| Otitis media/pneumonia/bronchiolitis | 13 (8.4) | 7 (4.9) |

| Parasitosis/diarrhea/vomiting | 11 (7.1) | 10 (7.0) |

| Seizures/cerebral palsy/neurologic disorders | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Exanthema/skin disease | 27 (17.5) | 21 (14.7) |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | 0 | 0 |

| Fever ≥3 d (≥3 episodes) | 11 (7.1) | 5 (3.5) |

| Malaria | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Meningitis | 0 | 0 |

| Other infections that required antibiotics | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.8) |

| Hearing problems | 0 (0.0) | 0 |

| Asthma | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Cardiovascular problems | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Blindness | 0 | 0 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 6 (3.9) | 0 |

| Any hemolytic condition | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.4) |

| Any malignancy | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Cow’s milk protein allergy | NA | 3 (2.1) |

| Food allergies | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2.1) |

| Injury trauma | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.8) |

| Any condition that required surgery | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.8) |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

NA, not applicable (data were not collected at the 1-year follow-up visit); UTI, urinary tract infection.

Data are given as median (interquartile range).

Growth and development from birth to 2 years of age

At 1 year of age, a comparison of the total cohort with the age- and sex-specific WHO Child Growth Standards showed that length and head circumference had a mean ± SD z-score of 0.0±1.1 for both measures and that the medians were at the 49th and 48th percentiles of the WHO Child Growth Standards, respectively; for weight, the mean z-score was 0.2±1.1 and median at the 58th percentile.

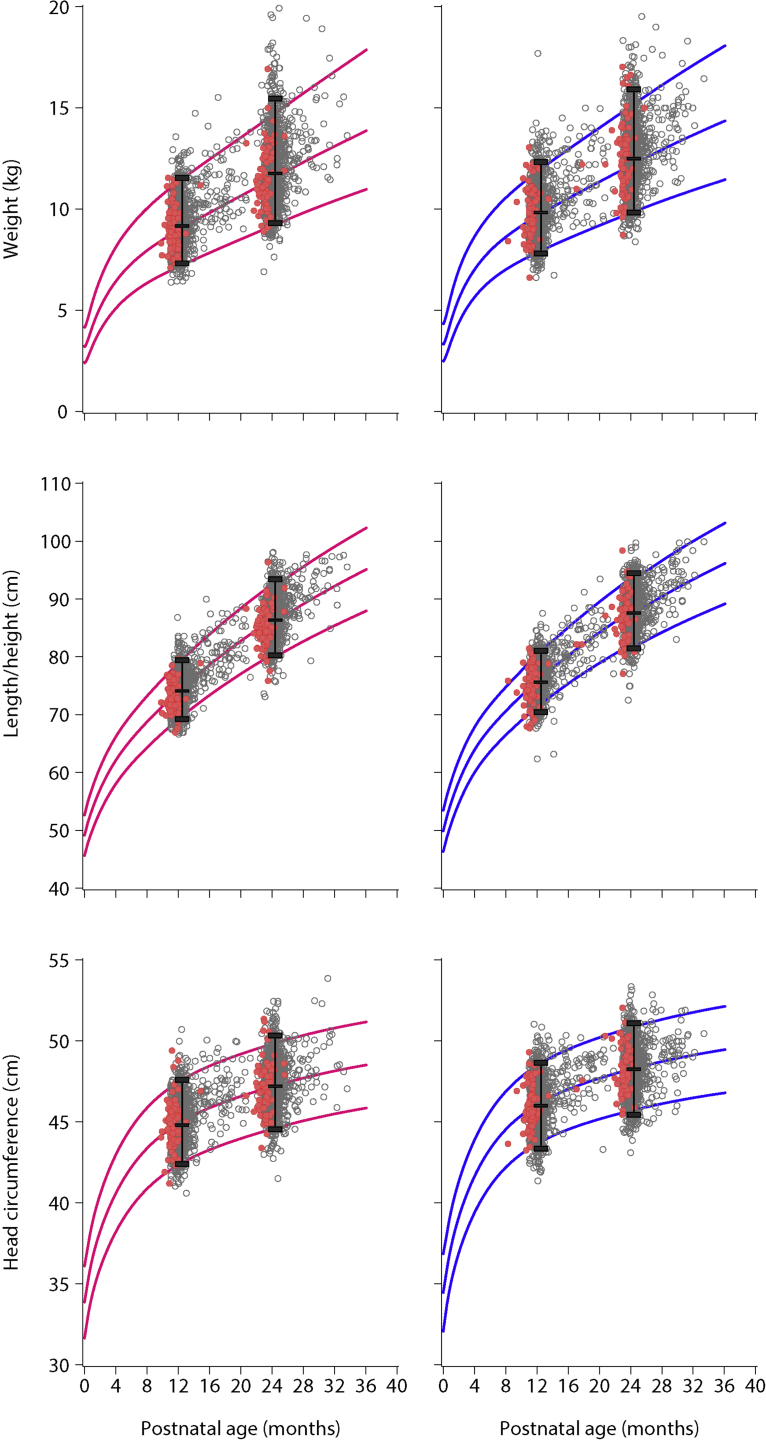

At the 2-year visit, the growth of the children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards plotted almost perfectly onto the WHO Child Growth Standards (ie, 93% for length, 91% for weight [with the expected larger variability], and 92% for head circumference, respectively. Our cohort’s values were within the 3rd and 97th cut-off points of the WHO Child Growth Standards (Table 5; Figure 2). For length and head circumference, the mean ± SD z-score was 0.0±1.1 for both measures, and the medians were at the 49th and 50th percentiles of the WHO Child Growth Standards, respectively. For weight, the mean ± SD z-score was 0.2±1.1, and median was at the 58th percentile. Figure 2 also shows the 3rd, 50th and 97th percentiles of the distributions of our data (the same percentiles of the WHO Child Growth Standards are included in Figure 2 at years 1 and 2). As shown, the percentiles from our population are almost identical to those of the WHO standards.

Table 5.

Anthropometric measures at 2 years of age of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 compared with the World Health Organization Child Growth Standardsa

| Variable | N | INTERGROWTH-21st |

World Health Organization Child Growth Standards |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±standard deviationb | Median (interquartile range) | Mean z-score±standard deviation | Median percentile | ||

| Weight, kg | 3025 | 12.3±1.7 | 12.2 (11.1–13.3) | 0.2±1.1 | 58 |

| Length, cm | 3010 | 87.4±3.6 | 87.3 (85.0–89.7) | 0.0±1.1 | 49 |

| Head circumference, cm | 3003 | 47.8±1.6 | 47.8 (46.7–48.8) | 0.0±1.1 | 50 |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Age and gender-specific z-scores and percentiles compared with the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards23

Mean values were estimated from raw data.

Figure 2.

Anthropometric measures at 1 and 2 years of age of the children included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards

Data are for children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 (grey circles) and children who were included in the Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 (red circles). Values are superimposed onto the 3rd, 50th, and 97th percentiles of the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards23 (girls [pink lines] and boys [blue lines]). For children born preterm, corrected postnatal age was used.

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

At 1 year of age, a comparison of the preterm cohort only with the age- and sex-specific WHO Child Growth Standards at postnatal corrected age, length, and head circumference had a mean z-score of 0.1 for both measures; the medians were at the 52nd percentiles of the WHO Child Growth Standards; for weight, the mean ± SD z-score was 0.2±1.1, and the median was at the 57th percentile.

At 2 years of age, the growth of the children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards also plotted similarly onto the WHO Child Growth Standards (Table 6; Figure 2). For length and head circumference, the mean ± SD z-scores were -0.1±1.2 and 0.0±1.1, respectively, and the median was at the 47th percentile for head circumference of the WHO Child Growth Standards for both measures. For weight, the mean ± SD z-score was 0.2±1.1, and the median was at the 53rd percentile.

Table 6.

Anthropometric measures at 2 years of age of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 compared with the World Health Organization Child Growth Standardsa

| Variable | N | INTERGROWTH-21st |

Comparison with World Health Organization Child Growth Standards |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±standard deviationb | Median (interquartile range) | Mean z-score±standard deviation | Median percentile | ||

| Weight, kg | 142 | 12.0±1.7 | 11.7 (10.8–13.2) | 0.2±1.1 | 53 |

| Length, cm | 141 | 86.2±3.7 | 86.2 (83.8–88.3) | –0.1±1.2 | 47 |

| Head circumference, cm | 140 | 47.7±1.6 | 47.6 (46.7–48.6) | 0.0±1.1 | 47 |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Corrected age was used to obtain age and gender-specific z-scores and percentiles comparing to the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards23

Mean values were estimated from raw data.

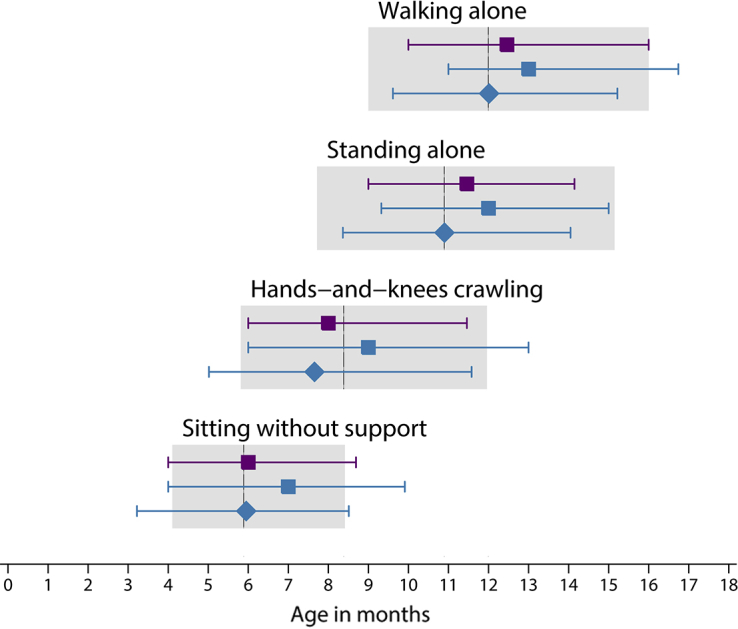

The mean postnatal ages, at which the 4 main WHO milestones for gross motor development29 were achieved for the total cohort and preterm subgroup (chronologic and corrected age) are presented in Figure 3. Both groups overlapped well for these milestones at the 50th, 3rd, and 97th percentiles of the WHO range for normal term infants. By 2 years of age, >99% of the children had achieved the 4 motor development milestones with >97% within the range of the WHO milestones (data not shown). However, although the preterm subgroup overlapped very well when corrected age was used, they displayed a delay of approximately 1 month in achieving the “walking alone” and “standing alone” milestones, when estimated age after birth was used (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Median age of achievement (3rd and 97th percentiles) of 4 gross motor development milestones

Data are for children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 (purple) and children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 (blue). The diamonds represent the use of corrected age for the children who were born preterm. For comparison, the 3rd and 97th percentiles of the World Health Organization windows of achievement35 for the same milestones are presented in grey (with the median shown as a vertical line).

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

The variability in children’s length among study sites compared with that among individuals within a study site

Maintaining the same analytic approach to the 2-year follow-up data that was adopted for the fetus and newborn infant,4, 16, 37 we summarized the variability in skeletal growth and size during pregnancy, at birth, and in infancy and childhood (ie, quantifying the variability among study sites, as opposed to that among individuals within a given site). We estimated that the variance among our study sites from birth through 1–2 years of age explains only 5.5% of the total variability in length between birth and 2 years of age; the variance among individuals within a study site explains 42.9% (ie, 8 times the amount after we controlled for age and sex). In Table 7, we compared the present results with the previously published INTERGROWTH-21st data from the first trimester of pregnancy to 2 years of age. In all these periods of rapid growth, the variance among sites explains <10% of the total variability in skeletal growth.

Table 7.

Variance components analysis for fetal, newborn infant, and childhood skeletal growth from the cohort of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project

| Variance | Fetal ultrasound measures16, % |

Size at birth16 (newborn infant lengtha), % | Infancy/childhood, % |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st-trimester fetal crown-rump lengtha | 2nd- and 3rd-trimester fetal head circumference | Preterm infant length22 | Present study lengthb |

||

| Among study sites | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 5.5 |

| Among individuals within a site | — | 18.6 | — | 57.1 | 42.9 |

| Residual | 98.1 | 78.8 | 96.5 | 42.7 | 51.6 |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Variance between individuals for these measures could not be estimated, given the cross-sectional nature of the data

Includes length measurements at birth, 1 and 2 years, controlled for age and sex.

Estimated adult height of the children included in the INTERGROWTH- 21st fetal growth standards

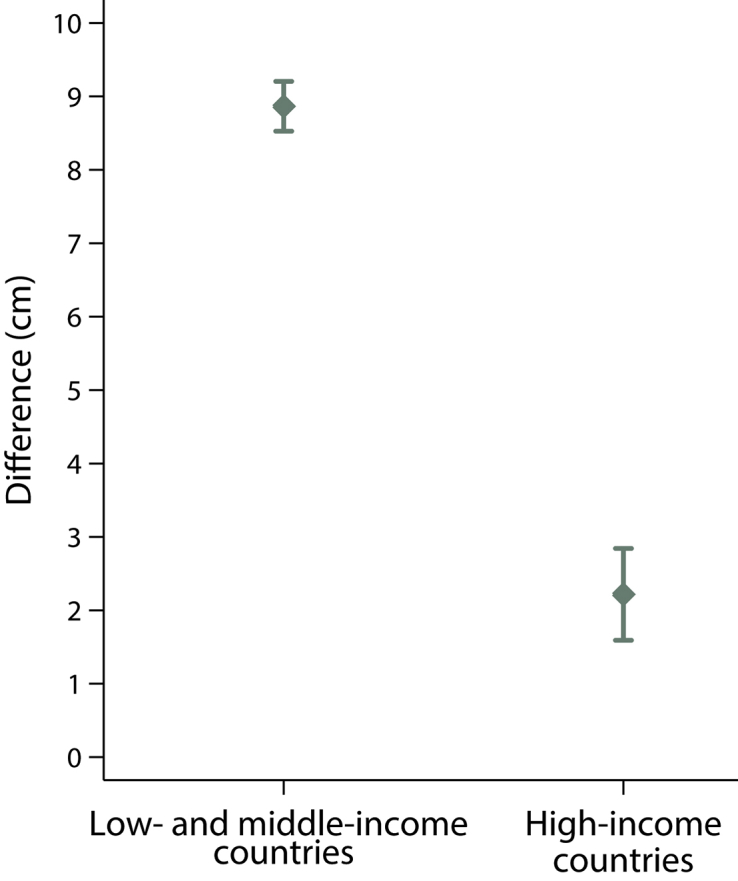

We estimated the difference between the observed mean parental height and the expected mean adult height (equal to approximately double the mean length at 2 years of age).37 In the study sites in low-middle income countries (n=1611), an increase in mean expected adult height of 8.9 cm over mean parental height is predicted to occur in a single generation, provided that infants and children are exposed to adequate health, environmental and nutritional conditions from early pregnancy onwards (Figure 4). Conversely, in high-income country sites (N=415), this cohort will be on average 2.2 cm taller than their parents (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expected increase from parental height

Mean (95% confidence interval) difference between estimated adult height (calculated by doubling infant length at 2 years of age) and mean parental height (calculated as the average of maternal and paternal heights) for children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 for study sites located in low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries.

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Comment

Main findings

The participants included in the construction of the Fetal Growth Standards, the Newborn Size at Birth and the Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project were selected during early pregnancy specifically to generate international standards.15 The comprehensive data presented here, which describe for the first time the postnatal physical growth, infant mortality rate, morbidity and motor development of the INTERGROWTH-21st participants, corroborate that they conformed to the WHO prescriptive approach for the construction of human growth standards. They are a cohort with continuous very low rates of clinical conditions that could affect optimal growth and development.

Our findings reinforce the a priori concept17 that it is possible to identify a subset of mostly moderate and late preterm infants, with no evidence of intrauterine growth restriction and limited neonatal morbidity,41 which constitutes an adequate approximation (in terms of growth, health, nutrition, and development) to a prescriptive population for the construction of preterm postnatal growth standards up to 64 weeks postmenstrual age, the time at which they match the WHO Child Growth Standards.22, 23

Strengths and limitations of the study in the context of the existing literature

As far as we are aware, this is the first time that a fetal cohort that has been included in longitudinal studies for the specific purpose of constructing prescriptive growth standards has been evaluated up to 2 years of age. Most ultrasound studies that aimed to create reference charts for fetal growth have not reported any postnatal assessment, nor is it likely that such an assessment has been carried out, given the time that has elapsed since these studies were conducted.9 We selected the 2-year milestone because nutrition indicators that are measured at this age are strongly predictive of adult measures of nutrition, human capital, attained height, and intelligence.42 Before the age of 2 years, it has been shown that children often cross growth percentiles, whereas after this age the phenomenon known as “growth channelization” has been demonstrated, because children tend to grow along the same percentile.20

Our unique data are derived from a prospective follow-up evaluation of individuals from 7 different regions of the world from the first trimester of pregnancy to 2 years of age. These findings strengthen the case for the worldwide use of the international INTERGROWTH-21st standards that complement the WHO Child Growth Standards in postnatal life. The similarities between the INTERGROWTH-21st and WHO studies mean that the size of children, measured at 2 years of age, who were born to healthy mothers, with adequate nutrition, from healthy populations at low risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, is consistent between the studies and across time.

Other strong features of the study include careful standardization of the outcome measures and the comprehensiveness of the standardized clinical and developmental assessments at 2 years of age.43 Furthermore, we followed 82% of the children and up to 86% of the preterm subgroup, which are excellent rates for free-living urban subjects. Baseline similarities between the infants who were evaluated and those lost to follow-up demonstrate that selection bias is very unlikely to have influenced the observed results.

We acknowledge some limitations that relate to practical difficulties of carrying out such a large, multicenter study.

First, the information on morbidity refers mostly to substantive clinical episodes, and data on gross motor development were obtained from parental report rather than direct observation; however, we informed parents about the Infant Follow-up Study protocol at enrolment and asked them to record severe conditions and infant developmental milestones. In addition, parents were encouraged to bring sick children for care to the participating centers; illness therefore was recorded at the time of the event.

Second, the study outcomes do not extend >2 years of age. This juncture was selected because it is a key time for the detection of postnatal growth faltering,44, 45 and an anthropometric and clinical evaluation at this age is a very good predictor of subsequent growth. Finally, the Seattle, WA, study site did not participate in the follow-up of children because of logistic issues that were associated with this inner city, highly mobile population. Although they represented only 298 newborn infants of more than 4000 in the total cohort and it is very unlikely that they would have affected the overall results presented here, it would have been better to have studied this subsample as well.

The WHO motor development assessment is a simple, pragmatic, and reliable tool to describe normal variation in the achievement of milestones that are reached progressively across infancy. It is especially recommended for studying a large number of infants at the cohort level, rather than individual level.35 We have observed that, using chronologic age, gross motor indicators for 2-year-old children who were born preterm (despite being always within WHO recommended windows) are below those of the total cohort by approximately 1 month. This pattern disappears with the use of corrected age (Figure 3). Thus, it is likely that the true range of development in uncomplicated preterm infants is between chronologic and corrected age. However, it is possible that levels of preterm postnatal development may be associated with etiologic phenotypes, as was shown with early neonatal morbidity.41 We presently are studying these issues in the INTERBIO-21st Study, which is the extension to the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.

In all the INTERGROWTH-21st publications, we have emphasized that the relevant question when comparing growth across populations is whether the variability in skeletal growth within a population (interindividual genetic difference) is larger than the variability among populations (interpopulation genetic difference) when nutritional and health needs are met.

We have used variance components analysis in cohorts that were followed prospectively to identify the proportional contribution of the within and between sites variance components.4, 16, 23 We have repeated this analysis for the present article (Table 7). The variance from birth to 2 years of age within a geographic area is 8 times larger than that among geographic areas (Table 7). Hence, it is very unlikely that variability among geographic areas explains >10% of the total variability in infant and child length in healthy, well-nourished, low-risk populations who receive adequate healthcare. These results are in very close agreement with the data from the WHO Child Growth Standards for children <5 years of age, where the variability within study sites explained 70% of the total variance as opposed to a figure of 3.4% that is explained by the between-study sites variability.23

This clinical/epidemiologic finding is of great biologic interest because it is consistent with a metaanalysis of 22 genome-wide association studies that showed that the polygenic scores, based on 180 single nucleotide polymorphisms that previously were associated with adult height, explained only a very small proportion of the total variance in birth and infant length (0.13% and 2.95%, respectively).46

Long-term implications

Our 2-year follow-up evaluation of this large cohort of healthy children allowed their mean predicted adult height to be estimated based on the assumption that health, nutritional, and socioeconomic conditions would remain adequate (Figure 4). Thus, the participants in the low-middle income countries sites (and by implication those from other similar countries) are expected to be approximately 8 cm taller as adults than the mean height of their parents; these data are very close to the 6.2–7.8 cm results that were observed in a similar, secondary analysis of the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study database.37 However, because optimal growth largely has been achieved in the parents from high-income country sites, their children are expected to be, on average, only 2.2 cm taller (Figure 4).

Our results confirm a pattern and magnitude of apparent transgenerational “washout”47 that has previously been described in the Multicentre Growth Reference Study populations.37 This effect on skeletal growth suggests that a highly sensitive response to environmental changes (eg, better intrauterine and infant nutrition and healthcare) can occur in 1 generation (ie, in a much shorter timeframe than evolution allows). The mechanisms, which may be mediated by modifications in gene expression that are not linked to DNA sequence changes, are being investigated currently at the molecular level in the INTERBIO-21st Study.

The observation that this healthy cohort was at the 58th percentile of the sex-specific weight for age of the WHO Child Growth Standards at 2 years of age has potential implications in describing the natural history of becoming overweight among healthy infants. Because we did not implement any specific nutritional intervention, other than to promote breastfeeding, this weight distribution may represent the initial stages of the overweight epidemic facing many urban children who are exposed to westernized diets. Recent standardized, prospectively collected, fetal data have confirmed the complex effect of nutrition, the environment, migration, and social-cultural issues on fetal growth patterns.48, 49, 50

The short-term shift in weight distribution in an otherwise healthy population that we have described also reinforces the concept that comparisons among populations to evaluate growth potential should be based on length rather than weight because of its sensitivity to acute influences.

A larger question that goes beyond the scope of this article relates to the timing, velocity, and individual tracking of growth from conception to 2 years of age vis-à-vis feeding and morbidity in high-risk populations. The exploration of these questions in a longitudinal fashion, including interactions, has considerable statistical complexity, which we are presently investigating in the INTERBIO-21st Study.

In summary, we have presented evidence that the participants who are enrolled in the international Fetal Growth Standards and the Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project and who were selected based on the WHO prescriptive approach for growth standards remain healthy and have adequate growth and development patterns at the key milestone of 2 years of age. This is additional strong confirmation of the sample’s appropriateness for the construction of international growth standards. The INTERGROWTH-21st international standards are freely available (www.intergrowth21.tghn.org) for use worldwide.

Contributors

J.V. and S.H.K. conceptualized and designed the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. J.V., S.H.K., D.G.A., and A.J.N. prepared the original protocol, with later input from A.T.P., L.C.I., F.C.B., and ZAB. J.V., A.T.P., L.C.I., A.L., and Z.A.B. supervised and coordinated the project’s overall undertaking. E.S.U., E.O.O., and D.G.A. carried out data management and analysis in collaboration with J.V. R.P., F.C.B., R.O., Y.A.J., E.B., and M.P. collaborated in the overall project and implemented it in their respective countries. F.G. assisted in the global coordination of the project; L.C.I. and C.C. led the quality control of the anthropometric component, and M.F. and A.S. led the neurodevelopment assessment component. J.V. and S.K. wrote the report with significant contributions by F.G., C.G., C.G.V., F.C.B., and Z.A.B. All coauthors read the report and made suggestions on its content.

Members of the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st) and its Committees

Scientific Advisory Committee: M. Katz (Chair from January 2011), M.K. Bhan, C. Garza, S. Zaidi, A. Langer, P.M. Rothwell (from February 2011), Sir D. Weatherall (Chair until December 2010).

Steering Committee: Z.A. Bhutta (Chair), J. Villar (Principal Investigator), S. Kennedy (Project Director), D.G. Altman, F.C. Barros, E. Bertino, F. Burton, M. Carvalho, L. Cheikh Ismail, W.C. Chumlea, M.G. Gravett, Y.A. Jaffer, A. Lambert, P. Lumbiganon, J.A. Noble, R.Y. Pang, A.T. Papageorghiou, M. Purwar, J. Rivera, C. Victora.

Executive Committee: J. Villar (Chair), D.G. Altman, Z.A. Bhutta, L. Cheikh Ismail, S. Kennedy, A. Lambert, J.A. Noble, A.T. Papageorghiou.

Project Coordinating Unit: J. Villar (Head), S. Kennedy, L. Cheikh Ismail, A. Lambert, A.T. Papageorghiou, M. Shorten, L. Hoch (until May 2011), H.E. Knight (until August 2011), E.O. Ohuma (from September 2010), C. Cosgrove (from July 2011), I. Blakey (from March 2011).

Data Analysis Group: D.G. Altman (Head), E.O. Ohuma, E. Staines Urias (from April 2016), J. Villar.

Data Management Group: D.G. Altman (Head), F. Roseman, N Kunnawar, S.H. Gu, J.H. Wang, M.H. Wu, M. Domingues, P. Gilli, L. Juodvirsiene, L. Hoch (until May 2011), N. Musee (until June 2011), H. Al-Jabri (until October 2010), S. Waller (until June 2011), C. Cosgrove (from July 2011), D. Muninzwa (from October 2011), E.O. Ohuma (from September 2010), D. Yellappan (from November 2010), A. Carter (from July 2011), D. Reade (from June 2012), R. Miller (from June 2012), ESU (from April 2016).

Ultrasound Group: A.T. Papageorghiou (Head), L. Salomon (Senior external advisor), A. Leston, A. Mitidieri, F. Al-Aamri, W. Paulsene, J. Sande, W.K.S. Al-Zadjali, C. Batiuk, S. Bornemeier, M. Carvalho, M. Dighe, P. Gaglioti, N. Jacinta, S. Jaiswal, J.A. Noble, K. Oas, M. Oberto, E. Olearo, M.G. Owende, J. Shah, S. Sohoni, T. Todros, M. Venkataraman, S. Vinayak, L. Wang, D. Wilson, Q.Q. Wu, S. Zaidi, Y. Zhang, P. Chamberlain (until September 2012), D. Danelon (until July 2010), I. Sarris (until June 2010), J. Dhami (until July 2011), C. Ioannou (until February 2012), C.L. Knight (from October 2010), R. Napolitano (from July 2011), S. Wanyonyi (from May 2012), C. Pace (from January 2011), V. Mkrtychyan (from June 2012).

Anthropometry Group: L. Cheikh Ismail (Head), W.C. Chumlea (Senior external advisor), F. Al-Habsi, Z.A. Bhutta, A. Carter, M. Alija, J.M. Jimenez-Bustos, J. Kizidio, F. Puglia, N. Kunnawar, H. Liu, S. Lloyd, D. Mota, R. Ochieng, C. Rossi, M. Sanchez Luna, Y.J. Shen, H.E. Knight (until August 2011), D.A. Rocco (from June 2012), I.O. Frederick (from June 2012).

Neonatal Group: Z.A. Bhutta (Head), E. Albernaz, M. Batra, B.A. Bhat, E Bertino, P. Di Nicola, F. Giuliani, I. Rovelli, K. McCormick, R. Ochieng, R.Y. Pang, V. Paul, V. Rajan, A. Wilkinson, A. Varalda (from September 2012).

Environmental Health Group: B. Eskenazi (Head), L.A. Corra, H. Dolk, J. Golding, A. Matijasevich, T. de Wet, J.J. Zhang, A. Bradman, D. Finkton, O. Burnham, F. Farhi.

Participating countries and local investigators

Brazil: F.C Barros (Principal Investigator), M. Domingues, S. Fonseca, A. Leston, A. Mitidieri, D. Mota, I.K. Sclowitz, M.F. da Silveira.

China: R.Y. Pang (Principal Investigator), Y.P. He, Y. Pan, Y.J. Shen, M.H. Wu, Q.Q. Wu, J.H. Wang, Y. Yuan, Y. Zhang.

India: M. Purwar (Principal Investigator), A. Choudhary, S. Choudhary, S. Deshmukh, D. Dongaonkar, M. Ketkar, V. Khedikar, N. Kunnawar, C. Mahorkar, I. Mulik, K. Saboo, C. Shembekar, A. Singh, V. Taori, K. Tayade, A. Somani.

Italy: E. Bertino (Principal Investigator), P. Di Nicola, M. Frigerio, G. Gilli, P. Gilli, M. Giolito, F. Giuliani, M. Oberto, L. Occhi, C. Rossi, I. Rovelli, F. Signorile, T. Todros.

Kenya: W. Stones and M. Carvalho (Co- Principal Investigators), J. Kizidio, R. Ochieng, J. Shah, S. Vinayak, N. Musee (until June 2011), C. Kisiang’ani (until July 2011), D. Muninzwa (from August 2011).

Oman: Y.A. Jaffer (Principal Investigator), J. Al-Abri, J. Al-Abduwani, F.M. Al-Habsi, H. Al-Lawatiya, B. Al-Rashidiya, W.K.S. Al-Zadjali, F.R. Juangco, M. Venkataraman, H. Al-Jabri (until October 2010), D. Yellappan (from November 2010).

UK: S. Kennedy (Principal Investigator), L. Cheikh Ismail, A.T. Papageorghiou, F. Roseman, A. Lambert, E.O. Ohuma, S. Lloyd, R. Napolitano (from July 2011), C. Ioannou (until February 2012), I. Sarris (until June 2010).

USA: M.G. Gravett (Principal Investigator), C. Batiuk, M. Batra, S. Bornemeier, M. Dighe, K. Oas, W. Paulsene, D. Wilson, I.O. Frederick, H.F. Andersen, S.E. Abbott, A.A. Carter, H. Algren, D.A. Rocco, T.K. Sorensen, D. Enquobahrie, S. Waller (until June 2011).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Health Authorities in Pelotas, Brazil; Beijing, China; Nagpur, India; Turin, Italy; Nairobi, Kenya; Muscat, Oman; Oxford, UK and Seattle, USA, who facilitated the project by allowing participation of these study sites as collaborating centers. We are extremely grateful to Philips Medical Systems who provided the ultrasound equipment and technical assistance throughout the project. We also thank MedSciNet U.K. Ltd for setting up the INTERGROWTH-21st web-site and for the development, maintenance and support of the on-line data management system.

We thank the parents and infants who participated in the studies and the more than 200 members of the research teams who made the implementation of this project possible. The participating hospitals included: Brazil, Pelotas (Hospital Miguel Piltcher, Hospital São Francisco de Paula, Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Pelotas, and Hospital Escola da Universidade Federal de Pelotas); China, Beijing (Beijing Obstetrics & Gynecology Hospital, Shunyi Maternal & Child Health Centre, and Shunyi General Hospital); India, Nagpur (Ketkar Hospital, Avanti Institute of Cardiology Private Limited, Avantika Hospital, Gurukrupa Maternity Hospital, Mulik Hospital & Research Centre, Nandlok Hospital, Om Women’s Hospital, Renuka Hospital & Maternity Home, Saboo Hospital, Brajmonhan Taori Memorial Hospital, and Somani Nursing Home); Kenya, Nairobi (Aga Khan University Hospital, MP Shah Hospital and Avenue Hospital); Italy, Turin (Ospedale Infantile Regina Margherita Sant’ Anna and Azienda Ospedaliera Ordine Mauriziano); Oman, Muscat (Khoula Hospital, Royal Hospital, Wattayah Obstetrics & Gynaecology Poly Clinic, Wattayah Health Centre, Ruwi Health Centre, Al-Ghoubra Health Centre and Al-Khuwair Health Centre); UK, Oxford (John Radcliffe Hospital) and USA, Seattle (University of Washington Hospital, Swedish Hospital, and Providence Everett Hospital). Full acknowledgement of all those who contributed to the development of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project protocol appears at www.intergrowth21.org.uk.

Footnotes

Supported by the INTERGROWTH-21st grant 49038 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the University of Oxford.

The funder played no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

José Villar, Email: jose.villar@obs-gyn.ox.ac.uk.

International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st):

M. Katz, M.K. Bhan, C. Garza, S. Zaidi, A. Langer, P.M. Rothwell, Sir D. Weatherall, Z.A. Bhutta, J. Villar, S. Kennedy, D.G. Altman, F.C. Barros, E. Bertino, F. Burton, M. Carvalho, L. Cheikh Ismail, W.C. Chumlea, M.G. Gravett, Y.A. Jaffer, A. Lambert, P. Lumbiganon, J.A. Noble, R.Y. Pang, A.T. Papageorghiou, M. Purwar, J. Rivera, C. Victora, M. Shorten, L. Hoch, H.E. Knight, E.O. Ohuma, C. Cosgrove, I. Blakey, E. Staines Urias, F. Roseman, N. Kunnawar, S.H. Gu, J.H. Wang, M.H. Wu, M. Domingues, P. Gilli, L. Juodvirsiene, N. Musee, H. Al-Jabri, S. Waller, D. Muninzwa, D. Yellappan, A. Carter, D. Reade, R. Miller, L. Salomon, A. Leston, A. Mitidieri, F. Al-Aamri, W. Paulsene, J. Sande, W.K.S. Al-Zadjali, C. Batiuk, S. Bornemeier, M. Dighe, P. Gaglioti, N. Jacinta, S. Jaiswal, K. Oas, M. Oberto, E. Olearo, M.G. Owende, J. Shah, S. Sohoni, T. Todros, M. Venkataraman, S. Vinayak, L. Wang, D. Wilson, Q.Q. Wu, Y. Zhang, P. Chamberlain, D. Danelon, I. Sarris, J. Dhami, C. Ioannou, C.L. Knight, R. Napolitano, S. Wanyonyi, C. Pace, V. Mkrtychyan, F. Al-Habsi, M. Alija, J.M. Jimenez-Bustos, J. Kizidio, F. Puglia, N. Kunnawar, H. Liu, S. Lloyd, D. Mota, R. Ochieng, C. Rossi, M. Sanchez Luna, Y.J. Shen, D.A. Rocco, I.O. Frederick, E. Albernaz, M. Batra, B.A. Bhat, E Bertino, P. Di Nicola, F. Giuliani, I. Rovelli, K. McCormick, V. Paul, V. Rajan, A. Wilkinson, A. Varalda, B. Eskenazi, L.A. Corra, H. Dolk, J. Golding, A. Matijasevich, T. de Wet, J.J. Zhang, A. Bradman, D. Finkton, O. Burnham, and F. Farhi

Appendix

Supplementary Table 1.

Twenty-four–hour dietary intake of children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Fetal Growth Standards21 at 1 and 2 years of age

| Food group given to the child at least once a day | 1 Year of age (n=2832), n (%) | 2 Years of age (n=3041), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Grains, roots, and tubers | 2811 (99.3) | 3031 (99.7) |

| Legumes and nuts | 1124 (39.7) | 1375 (45.2) |

| Dairy products | 2822 (99.6) | 3040 (100.0) |

| Flesh foods | 1676 (59.2) | 2083 (68.5) |

| Eggs | 575 (20.3) | 889 (29.2) |

| Vitamin-A-rich fruits | 1907 (67.3) | 1950 (64.1) |

| Other fruits and vegetables | 2606 (92.0) | 2863 (94.1) |

| Fats: spreads/oils | 885 (31.3) | 1342 (44.1) |

| Sugars: sweets/sugar products/jelly/sweetened drinks | 435 (15.4) | 989 (32.5) |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

Supplementary Table 2.

Twenty-four–hour dietary intake for children who were included in the INTERGROWTH-21st Preterm Postnatal Growth Standards22 evaluated at 1 and 2 years of age

| Food group given to the child at least once a day | 1 Year of age (n=154) | 2 Years of age (n=143) |

|---|---|---|

| Grains, roots, and tubers | 153 (99.4) | 142 (99.3) |

| Legumes and nuts | 54 (35.1) | 68 (47.6) |

| Dairy products | 154 (100.0) | 143 (100.0) |

| Flesh foods | 95 (61.7) | 101 (70.6) |

| Eggs | 35 (22.7) | 35 (24.5) |

| Vitamin-A-rich fruits | 104 (67.5) | 84 (58.7) |

| Other fruits and vegetables | 130 (84.4) | 133 (93.0) |

| Fats: spreads/oils | 34 (22.1) | 55 (38.5) |

| Sugars: sweets/sugar products/jelly/sweetened drinks | 14 (9.1) | 45 (31.5) |

Villar et al. Validation of the INTERGROWTH-21st fetal growth standards. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Screening, assessment and management of neonates and infants with complications associated with Zika virus exposure in utero: Interim guidance update. 2016; WHO/ZIKV/MOC/16.3 Rev.2. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204475/1/WHO_ZIKV_MOC_16.3_eng.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2016.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Congenital microcephaly case definitions. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/public-health-partners/microcephaly-case-definitions.html. Accessed November 30, 2016.

- 3.Lee A.C.C., Kozuki N., Cousens S. Estimates of burden and consequences of infants born small for gestational age in low and middle income countries with INTERGROWTH-21st standard: analysis of CHERG datasets. BMJ. 2017;358:3677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villar J., Papageorghiou A.T., Pang R. Monitoring human growth and development: a continuum from the womb to the classroom. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villar J, Giuliani F, Barros FC, et al. Monitoring the postnatal growth of preterm infants: a paradigm change. Pediatrics 2018 Jan 4. pii: e20172467. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2467. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Robinson H.P. Sonar measurement of fetal crown-rump length as means of assessing maturity in first trimester of pregnancy. Br Med J. 1973;4:28–31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5883.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson H.P., Fleming J.E. A critical evaluation of sonar “crown-rump length” measurements. BJOG. 1975;82:702–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1975.tb00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvert J.P., Crean E.E., Newcombe R.G., Pearson J.F. Antenatal screening by measurement of symphysis-fundus height. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:846–849. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6345.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannou C., Talbot K., Ohuma E. Systematic review of methodology used in ultrasound studies aimed at creating charts of fetal size. BJOG. 2012;119:1425–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadlock F.P., Harrist R.B., Sharman R.S., Deter R.L., Park S.K. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadlock F.P., Harrist R.B., Martinez-Poyer J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: a sonographic weight standard. Radiology. 1991;181:129–133. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck Louis G.M., Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies’ Research Team, Grewal J. Clarification of estimating fetal weight between 10-14 weeks gestation, NICHD fetal growth studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acharya G., Wilsgaard T., Berntsen G.K., Maltau J.M., Kiserud T. Reference ranges for serial measurements of umbilical artery Doppler indices in the second half of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:937–944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villar J., Altman D.G., Purwar M. The objectives, design and implementation of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):9–26. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Onis M., Habicht J.P. Anthropometric reference data for international use: recommendations from a World Health Organization Expert Committee. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:650–658. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.4.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villar J., Papageorghiou A.T., Pang R. The likeness of fetal growth and newborn size across non-isolated populations in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study and Newborn Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:781–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villar J., Knight H.E., de Onis M. Conceptual issues related to the construction of prescriptive standards for the evaluation of postnatal growth of preterm infants. Arch Dis Childhood. 2010;95:1034–1038. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.175067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertino E., Di Nicola P., Giuliani F. Evaluation of postnatal growth of preterm infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(suppl2):9–11. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.601921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliani F., Cheikh Ismail L., Bertino E. Monitoring postnatal growth of preterm infants: present and future. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:635S–647S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.106310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victora C.G., Adair L., Fall C. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. 2008;371:340–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papageorghiou A.T., Ohuma E.O., Altman D.G. International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:869–879. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villar J., Giuliani F., Bhutta Z.A. Postnatal growth standards for preterm infants: the Preterm Postnatal Follow-up Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e681–e691. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Onis M., Garza C., Onyango A.W., Martorell R. WHO child growth standards. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;450:1–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eskenazi B., Bradman A., Finkton D. A rapid questionnaire assessment of environmental exposures to pregnant women in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):129–138. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheikh Ismail L., Knight H., Ohuma E. Anthropometric standardisation and quality control protocols for the construction of new, international, fetal and newborn growth standards: the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):48–55. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Onis M., Onyango A.W., Van den Broeck J., Chumlea W.C., Martorell R. Measurement and standardization protocols for anthropometry used in the construction of a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(suppl1):S27–S36. doi: 10.1177/15648265040251S104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheikh Ismail L., Knight H., Ohuma E. Anthropometric protocols for the construction of new international fetal and newborn growth standards: the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):42–47. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Onis M., Garza C., Victora C.G., Onyango A.W., Frongillo E.A., Martines J. The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study: planning, study design, and methodology. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(suppl1):S15–S26. doi: 10.1177/15648265040251S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wijnhoven T.M., de Onis M., Onyango A.W. Assessment of gross motor development in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Food Nutr Bull. 2004;25(suppl1):S37–S45. doi: 10.1177/15648265040251S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhutta Z., Giuliani F., Haroon A. Standardisation of neonatal clinical practice. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):56–63. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koletzko B., Goulet O., Hunt J. 1. Guidelines on Paediatric Parenteral Nutrition of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), Supported by the European Society of Paediatric Research (ESPR) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(suppl2):S1–S87. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000181841.07090.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edmond K, Bahl R. Optimal feeding of low-birth-weight infants. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43602/1/9789241595094_eng.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2017.

- 33.Cheikh Ismail L., Giuliani F., Bhat B.A. Preterm feeding recommendations are achievable in large-scale research studies. BMC Nutr. 2016;2:9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding. 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 35.Group WHO MGRS WHO Motor Development Study: windows of achievement for six gross motor development milestones. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;450:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perumal N., Gaffey M.F., Bassani D.G., Roth D.E. WHO child growth standards are often incorrectly applied to children born preterm in epidemiologic research. J Nutr. 2015;145:2429–2439. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.214064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garza C., Borghi E., Onyango A.W., de Onis M., WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group Parental height and child growth from birth to 2 years in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(suppl2):58–68. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewey K.G., Cohen R.J., Arimond M., Ruel M.T. Academy for Educational Development (AED); Washington (DC): 2005. Developing and validating simple indicators of complementary food intake and nutrient density for breastfed children in developing countries: final report. [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. de Onis M. Complementary feeding in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;450:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohuma E., Hoch L., Cosgrove C. Managing data for the international, multicentre INTERGROWTH-21st Project. BJOG. 2013;120(suppl2):64–70. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barros F.C., Papageorghiou A.T., Victora C.G. The distribution of clinical phenotypes of preterm birth syndrome: implications for prevention. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:220–229. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner J.M. Harvard University Press; Cambridge (MA): 1978. Fetus into man: physical growth from conception to maturity. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gladstone M., Oliver C., Van den Broek N. Survival, morbidity, growth and developmental delay for babies born preterm in low and middle income countries - a systematic review of outcomes measured. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Victora C.G., de Onis M., Hallal P.C., Blossner M., Shrimpton R. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e473–e480. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Black R.E., Victora C.G., Walker S.P. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van der Valk R.J., Kreiner-Moller E., Kooijman M.N. A novel common variant in DCST2 is associated with length in early life and height in adulthood. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1155–1168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burggren W.W. Dynamics of epigenetic phenomena: intergenerational and intragenerational phenotype ‘washout’. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:80–87. doi: 10.1242/jeb.107318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pugh S.J., Albert P.S., Kim S. Patterns of gestational weight gain and birthweight outcomes in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Fetal Growth Studies-Singletons: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:346.e1–346.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wing D.A., Ortega-Villa A.M., Grobman W.A. Maternal stress and neonatal anthropometry: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:82.e1–82.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buck Louis G.M., Grewal J., Albert P.S. Racial/ethnic standards for fetal growth: the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:449.e1–449.e41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]