Abstract

Objective

Evaluate the impact of a grab-and-go component embedded within a larger intervention designed to promote School Breakfast Program (SBP) participation.

Design

Secondary data analysis.

Setting

Rural Minnesota high schools.

Participants

Eight schools were enrolled in the grab-and-go only intervention component. An at-risk sample of students (n=364) who at baseline reported eating breakfast ≤3 days/week were enrolled at these schools.

Interventions

Grab-and-go style breakfast carts and policies were introduced to allow all students to eat outside the cafeteria.

Main Outcome Measures

Administrative records were used to determine percent SBP participation (proportion of non-absent days that fully-reimbursable meal was received) for each student and school-level averages.

Analysis

Linear mixed models.

Results

School-level increases in SBP participation from baseline to implementation school year were observed for schools enrolled in the grab-and-go only component (13.0% to 22.6%). Student-level increases in SBP participation were observed among the at-risk sample (7.6% to 21.9%) and among subgroups defined by free/reduced-price meal eligibility and ethnic/racial background. Participation in the SBP increased among students eligible for free/reduced-price meals from 13.9% to 30.7% and among ineligible students from 4.3% to 17.2%.

Conclusions and Implications

Increasing access to the SBP and social support for eating breakfast are effective promotion strategies. (200 words)

Keywords: Breakfast, Meals, Outcome assessment, Schools, Students

INTRODUCTION

A growing body of research documents the importance of eating breakfast for adolescent health and academic success.1–3 Eating breakfast provides an opportunity to improve overall nutrient intake and is linked to higher adolescent consumption of healthful dietary components such as iron, fiber, and calcium.2, 3 Young people who consume breakfast tend to have better mental health and lower risk of overweight.1, 3, 4 Further, there is evidence that skipping breakfast has a detrimental impact on alertness, attention, memory, problem solving, mathematics, and other aspects of cognitive performance.1 Participation in the U.S. Department of Agriculture School Breakfast Program (SBP) is therefore likely to promote academic achievement and is also associated with fewer psychosocial problems and reduced absenteeism.1

Despite the many benefits of eating breakfast, this meal is frequently skipped by a high percentage of U.S. adolescents. National surveillance data indicate that approximately six out of 10 high school students do not eat breakfast every day and 14% of young people this age skip breakfast on most or all days of the week.5 The prevalence of skipping breakfast is disproportionately high among older adolescents and marginalized groups of young people such as adolescents in lower-income households and those who identify with an ethnic/racial background other than non-Hispanic white.1 For example, the prevalence among high school students of skipping breakfast on most days is 12% for non-Hispanic white adolescents, 15% for Hispanic adolescents, and 18% for Black adolescents.5 Little is known regarding how the eating behaviors of rural adolescents compare to those of their urban counterparts;6 however, the prevalence of overweight is greater among rural students and related research evidence indicates that rural schools are less likely than urban schools to report having strong policies and practices to promote healthy eating behaviors.7–9

Promoting participation in the SBP has particular potential to help reduce existing disparities in adolescent nutrition and academic outcomes. While low-income adolescents and those in families with parents having lower levels of education are more likely to skip breakfast, these groups of young people may be more likely to eat a no-cost or low-cost breakfast at school.10–13 The SBP is an underutilized food support program; just over half of students that receive a free/reduced-price school lunch also participate in the SBP.14 As federal regulations require that a balanced selection of healthful foods be provided as part the SBP, it also represents a source of breakfast food guaranteed to provide key nutrients.15 There is a need for the evaluation of interventions to promote SBP participation that are feasible to implement in rural schools with potentially limited existing resources to promote healthy eating and that incorporate strategies relevant to low-income and ethnically/racially diverse young people.

Lack of time to eat breakfast before classes begin and lack of appetite in the morning are common barriers to SBP participation among diverse groups of young people.16, 17 Recommended strategies for addressing these barriers and promoting SBP participation are allowing students to purchase breakfast from a grab-and-go style cart later in the morning and eat breakfast outside of the cafeteria.18–20 Evaluation efforts suggest these strategies are feasible and well-accepted,21–24 but most evaluations to date have been carried out in elementary schools and middle schools and particularly few evaluations have been carried out in rural areas.18, 19, 23–25

The current study was designed to build on existing evaluation findings by evaluating the grab-and-go component of an intervention for rural high schools and guide the efforts of schools without the financial resources to implement a more intensive, multi-component approach such as the full Project BreakFAST intervention.25 The full-intensity Project BreakFAST intervention used multiple approaches to increase student access to school breakfast and address normative and attitudinal beliefs using SBP-focused marketing.25, 26 The first aim of the current study, which focused on implementation of the grab-and-go component of Project BreakFAST, was to examine the impact of implementation on school-level changes in SBP participation. The second aim was to examine the impact of the grab-and-go component among students with irregular breakfast habits and assess whether changes in SBP participation were related to eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals and ethnicity/race. In addition, the impact of the grab-and-go component on school-level participation in the SBP was compared to the impact of the full-intensity and more resource-intensive Project BreakFAST intervention approach to promoting breakfast consumption.

METHODS

Study Design and School Randomization

This secondary analysis used data from Project BreakFAST (Fueling Academics and Strengthening Teens), a group-randomized trial aimed at increasing SBP participation through the implementation of policy and environmental supports in rural Minnesota high schools.26 A convenience sample of 16 schools was recruited through an open invitation posted on the Minnesota School Nutrition Association website and electronic mailing list. Several informational webinars were additionally conducted for school personnel (e.g., principal, food service director) who responded to the invitation. Schools were evaluated for study inclusion based on location outside of the seven-county metropolitan region; not having a grab-and-go reimbursable school breakfast option; and having low participation (under 20%) in the SBP. Further consideration was also given to enrollment size (over 500 students) and the ethnic/racial composition of students (at least 10% identified as Hispanic or a race other than white).

Eight schools were randomly assigned to implement the full-intensity intervention and the remaining schools were asked to implement only the grab-and-go component on a delayed schedule. For logistical and budgetary reasons, schools were also divided into two implementation waves prior to random assignment (although three additional schools were recruited after randomization for Wave 1 but prior to randomization for Wave 2).26 Implementation was carried out in waves aligned with successive school years. Four Wave 1 schools implemented the full-intensity intervention during the 2013–2014 school year while the four other Wave 1 schools served as a control condition during 2013–2014 and then implemented the grab-and-go component during the 2014–2015 school year. Likewise, four Wave 2 schools implemented the full-intensity intervention in 2014–2015 while the four other Wave 2 schools served as a control condition during 2014–2015 and then implemented the grab-and-go component during the 2015–2016 school year. Additional details of the design and randomization process are published elsewhere.26 All study procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee. A memorandum of understanding was developed with each school to outline roles and responsibilities and was signed by the principal, food service director, and principal investigator of the research team prior to randomization.

At-risk Student Sample

A cohort of students with irregular breakfast habits was also enrolled in Project BreakFAST. All ninth and tenth grade students enrolled at the participating schools were asked to complete a brief screening survey to determine eligibility for participation unless they were absent on the day when data collection took place. Of the 5,767 students who completed the screening survey, a total of 2,512 students were determined to be eligible based on proficiency in English, having access to a telephone, typically being present at the beginning of the school day, and eating breakfast on no more than three days per school week. Parents of eligible students were notified and asked to contact the study team within 10 days if they did not want their child to participate. Project BreakFAST then invited 50–75 randomly selected students to participate at each school from the eligible sample with parental consent; students who identified as Hispanic or a race other than white were oversampled to meet an enrollment goal of 30%. A total of 904 students provided informed assent, including 364 students who were enrolled at one of the grab-and-go component treatment schools. Additional details of the consent and assent process have been previously published.26

Description of the Full-intensity Intervention and Grab-and-Go Component Treatments

The primary focus of Project BreakFAST was on environmental factors in the high school setting that potentially mediate student intention to eat school breakfast. Intervention components included (1) facilitating increased availability and accessibility of the SBP through school-wide policy and practice implementation; (2) providing opportunities for positive interactions that encourage school breakfast with social support and role modeling from peers and teachers; and (3) addressing normative and attitudinal beliefs through a school-wide SBP marketing campaign. Availability and access were addressed by implementing a grab-and-go style cart before school or a second chance breakfast line located in a high traffic area. Each school was provided with $5000 to implement this change to their program along with training by University of Minnesota Extension staff on best practices for providing school breakfast. The training for foodservice directors and principals was developed collaboratively by the Minnesota Department of Education and Extension to ensure the promoted strategies would support regulatory compliance and integrity; however, not all schools received the same form of training and extent of support for implementation. Most participating schools received a face-to-face training session, but the training for Wave 2 grab-and-go component schools was prerecorded. Implementation support from Extension staff was proactive and more extensive for full-intensity intervention schools than for schools assigned to implement only the grab-and-go component on a delayed schedule. Positive interactions were addressed through the development of school policies. If a policy allowing students to eat breakfast in the hallway was not already in place, schools were encouraged to implement such a policy and also allow eating breakfast in some classrooms when appropriate. Additionally, teachers and school staff were asked to encourage the breakfast program. Norms and attitudes around breakfast were addressed through support for school-wide marketing campaigns. Campaigns were developed at a cost of approximately $4000 by a community partner that worked with a group of students at each full-intensity intervention school to design promotional materials; however, this component was not included as part of the grab-and-go component. To document fidelity to the full-intensity intervention, process measures were collected by trained measurement staff during four unannounced school visits. Process measurement visits occurred during breakfast service to allow for the completion of fidelity checklists and tracking forms were used to document communication and promotional strategies. More detailed information regarding the theoretical and best practices driven intervention model, implementation, and process measures are available in previous publications.25, 26 All intervention and training materials are also available on the project website at z.umn.edu/projectbreakfast.

Measures

SBP participation

The targeted outcome, SBP participation, was measured by collecting records from each school across three school years. For full-intensity intervention schools, Time 1 data were collected to represent baseline participation among all incoming ninth and tenth grade students during the school year prior to the intervention; Time 2 data were collected to represent participation among tenth and eleventh grade students during the school year of intervention implementation; and Time 3 data were collected to represent participation among eleventh and twelfth grade students during the school year following implementation. For grab-and-go component schools, there were two school years of baseline measures (Time 1 and Time 2) and Time 3 represented the school year of intervention implementation. The deidentified administrative records that were collected for each individual student enrolled at a school included number of attendance days and the number of days that school breakfast was purchased. Using this information, percent SBP participation for an individual student in one year was defined as the proportion of days attended that a student received a fully-reimbursable school breakfast. School-level mean percent SBP participation was then summarized as the average of the individual student participation for students enrolled for at least 30 days of the school year. Individual student-level participation for the cohort of students with baseline irregular breakfast habits was likewise measured.

Other measures

Characteristics of students enrolled at participating schools were examined as covariates in analytic models. The administrative records collected from each school additionally included grade level, eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals, ethnicity/race, and absences for students in the cohort sample and all other enrolled students. School-level summary variables were defined as percentages of students enrolled in tenth grade (as a proxy for age), eligible for free/reduced-price school meals, identifying as non-Hispanic white, and chronically absent (more than 10% of days enrolled).

Statistical analysis

Change in school-level SBP participation over time was evaluated using linear mixed models. Models included a random intercept to account for the correlation among repeated measures within each school. Models also included the main fixed effect of time and school-level covariates, which were specifically wave assignment, percent of students eligible for free/reduced-price school meals, percent of non-Hispanic white students, percent of students chronically absent, and percent of students in tenth grade. Interaction between eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals and time and interaction between ethnicity/race and time were examined. Change in each school year and change in each month of the school year were analyzed. The impact of the grab-and-go component and the impact of the full-intensity Project BreakFAST intervention on school-level SBP were compared using a linear mixed model that included fixed effects of treatment intensity group, time, and their interaction along with the same school-level covariates.

Change in student-level SBP participation over time was also analyzed using linear mixed models. Student-level SBP participation was log-transformed before fitting the model, because the distribution was right skewed. This model included the main fixed effect of time, random effect of school, wave assignment of the school that the student attended, student’s eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals, ethnicity/race (non-Hispanic white or other), chronic absenteeism (yes or no), and grade level. Interaction between eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals and time and interaction between ethnicity/race and time were again examined for this model. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine whether the observed overall effect was different by eligibility for free/reduced-price meals (free/reduced-price or full price meals) and ethnicity/race (Non-Hispanic white or other). All analyses were conducted as intention-to-treat. Analysis was performed using Statistical Analysis Software (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). An alpha level of .05 and two-sided tests were used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participating Schools and Students

Among the eight schools that were assigned to the grab-and-go component treatment, the average total enrollment for ninth and tenth grade was approximately 400 students at Time 1. About half (47%) of enrolled students were female, 34% were eligible for free/reduced-price school meals, and nearly 83% identified their ethnic/racial background as non-Hispanic white. Chronic absenteeism was low with 92% of students missing fewer than 10% of school days. One school was located in a city, four schools were located in communities classified as rural town fringe (i.e., close to suburbs), and three schools were located in more rural communities classified as small towns. Seven of the eight schools chose to implement the grab-and-go component treatment and, at Time 3, had begun serving breakfast from a grab-and-go style cart before school or a second chance breakfast line located in a high traffic area.

The high-risk sample of students enrolled at one of the eight grab-and-go component treatment schools was demographically similar to the overall population of students enrolled at grab-and-go component schools. Just over half (55%) of participants were female, 35% were eligible for free/reduced-price school meals, and 78% identified their ethnic/racial background as non-Hispanic white. Most students (96%) were absent on fewer than 10% of school days.

The population of students enrolled at schools assigned to the full-intensity treatment was also demographically similar to the students enrolled at grab-and-go component schools. As described elsewhere,25 no significant differences were found between these groups in regards to total enrollment, enrollment in ninth and tenth grades, eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals, ethnic/racial background, and chronic absenteeism.

School-level Changes in SBP Participation

Analyses addressing the first research aim showed there were increases in school-level SBP participation following implementation of the grab-and-go component treatment. There was an overall average increase in school-level SBP participation (Table 1) and greater participation in each month of the school year (Figure 1). Participation in the SBP increased from 13.0% at Time 1 to 22.6% at Time 3 (P=.025) and from 13.9% at Time 2 to Time 3 (P=.017). At each time point, SBP participation tended to increase across the year from September to May but mean SBP participation for each month at Time 3 was higher in comparison to the same month at Time 1. Results were similar when analyses were repeated for the subset of seven schools that chose to implement the grab-and-go component treatment (data not shown).

Table 1.

School-level Average Percent School Breakfast Program Participation Before and During Implementation of only the Grab-and-Go Component of the Project BreakFAST Intervention in 8 Rural Minnesota High Schools

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Range | P values for changea | |

|

|

|||||

| Time 1b | 13.0 | 4.1 | 13.1 | 7.8–17.5 | |

| Time 2c | 13.9 | 3.7 | 13.2 | 7.9–18.0 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .91 |

| Time 3d | 22.6 | 5.0 | 21.9 | 17.7–33.7 | Time 3 versus Time 1: .025 Time 3 versus Time 2: .017 |

Model includes the following components (P value): fixed effect of time (Time 1 P=.001, Time 2 P=.007, Time 3=reference), wave assignment (Wave 1 P=.31, Wave 2 = reference), percent of students eligible for free/reduced-price school meals (P=.33), percent of students that identify as non-Hispanic white race (P=.002), percent of students chronically absent (P=.47), and percent of students in 10th grade (P=.01). The corrected Akaike Information Criterion for this model is 89.3. The P values presented in the table are adjusted values using the Tukey-Kramer method to account for multiple comparisons.

Time 1 represents the first baseline school year of participation among all incoming 9th and 10th grade students.

Time 2 represents the second baseline school year of participation among 10th and 11th grade students.

Time 3 represents participation of 11th and 12th grade students during the school year of implementation.

Figure 1.

School-level Average Percent School Breakfast Program Participation by Month in the School Years Before and During Implementation of the Grab-and-Go Component of the Project BreakFAST Intervention in Rural Minnesota High Schools (N=8)a,b,c

aTime 1 represents the first baseline school year of participation among all incoming 9th and 10th grade students.

bTime 2 represents the second baseline school year of participation among 10th and 11th grade students.

cTime 3 represents participation of 11th and 12th grade students during the school year of implementation.

Student-level Changes in SBP Participation

Student-level analyses addressing the second research aim also showed there were increases in SBP participation from Time 1 to Time 3 and from Time 2 to Time 3 among the group of high-risk students (Table 2). Increases in SBP participation were observed among the overall group of breakfast skippers and among subgroups of students defined by eligibility for free/reduced-price meals and ethnic/racial background. Among the overall group of breakfast skippers, there were statistically significant increases in mean SBP participation from 7.6% at Time 1 to 21.9% at Time 3 (P<.001) and from 10.0% at Time 2 to Time 3 (P<.001).

Table 2.

Student-level Average Percent School Breakfast Program Participation Before and During Implementation of only the Grab-and-Go Component of the Project BreakFAST Intervention among a Cohort of Rural Minnesota High School Students

| Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Range | P values for changea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sample (N=364)

| |||||

| Time 1c | 7.6 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 0–81.9 | |

| Time 2d | 10.0 | 17.7 | 1.3 | 0–92.2 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .29 |

| Time 3e | 21.9 | 25.6 | 11.3 | 0–95.2 | Time 3 versus Time 1: <.001 Time 3 versus Time 2: <.001 |

|

Students Eligible for Free/Reduced-Price School Meals (n=126) | |||||

| Time 1c | 13.9 | 18.8 | 5.4 | 0–81.9 | |

| Time 2d | 19.5 | 24.7 | 7.6 | 0–92.2 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .71 |

| Time 3e | 30.7 | 30.5 | 22.2 | 0–95.2 | Time 3 versus Time 1: <.001 Time 3 versus Time 2: <.001 |

|

Students Not Eligible for Free/Reduced-Price School Meals (n=238) | |||||

| Time 1c | 4.3 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 0–44.6 | |

| Time 2d | 5.0 | 9.3 | 0.6 | 0–46.1 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .70 |

| Time 3e | 17.2 | 21.2 | 7.8 | 0–87.0 | Time 3 versus Time 1: <.001 Time 3 versus Time 2: <.001 |

|

Students of Non-Hispanic White Race (n=284) | |||||

| Time 1c | 6.2 | 11.7 | 0.9 | 0–66.3 | |

| Time 2d | 8.0 | 14.7 | 1.2 | 0–89.9 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .32 |

| Time 3e | 19.7 | 23.5 | 9.8 | 0–90.1 | Time 3 versus Time 1: <.001 Time 3 versus Time 2: <.001 |

|

Students of Hispanic Ethnicity or a Non-white Race (n=80) | |||||

| Time 1c | 13.0 | 18.5 | 4.6 | 0–81.9 | |

| Time 2d | 17.1 | 24.5 | 2.9 | 0–92.2 | Time 2 versus Time 1: .93 |

| Time 3e | 29.5 | 30.9 | 19.8 | 0–95.2 | Time 3 versus Time 1: <.001 Time 3 versus Time 2: <.001 |

Models are based on log-transformed percent School Breakfast Program participation. The overall sample model includes a random effect of school and the following fixed effect components (P value): time (Time 1 P<.001, Time 2 P<.001, Time 3=reference), wave assignment (Wave 1 P=.51, Wave 2 = reference), eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals (P<.001), ethnicity/race (P=.64), chronic absenteeism (P=.32), and baseline grade level (P=.36). The P values presented in the table are adjusted values using the Tukey-Kramer method to account for multiple comparisons. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for the overall model is 4618.6.

Fit was also examined for the following subsample models: Students Eligible for Free/Reduced-Price School Meals (AIC=1645.6), Students Not Eligible for Free/Reduced-Price School Meals (AIC=2987.9), Students of Non-Hispanic White Race (AIC=3601.0), Students of Hispanic Ethnicity or a Non-white Race (AIC=1012.3).

Time 1 represents the first baseline school year of participation for incoming 9th and 10th grade students.

Time 2 represents the second baseline school year of participation for 10th and 11th grade students.

Time 3 represents participation of 11th and 12th grade students during the school year of implementation.

Although mean SBP participation among students eligible for free/reduced-price meals was higher at Time 1 than among students paying full price (P<.001), increases of similar magnitude were observed for both groups following implementation of the grab-and-go component treatment. There was no significant interaction between eligibility for free/reduced-price meals and time (P=0.27). Participation in the SBP among students eligible for free/reduced-price meals increased from 13.9% at Time 1 to 30.7% at Time 3 (P<.001). Similarly, SBP participation among students paying full price increased from 4.3% at Time 1 to 17.2% at Time 3 (P<.001).

Time 1 mean SBP participation was lower among non-Hispanic white students than among students that identified with an ethnic/racial background other non-Hispanic white (P<.001). However, increases in mean SBP participation were observed among both groups. There was no significant interaction between race and time (P=.66). Participation in the SBP among non-Hispanic white students more than tripled with an increase from 6.2% at Time 1 to 19.7% at Time 3 (P<.001). Similarly, SBP participation increased among students that identified with other ethnic/racial backgrounds from 13.0% at Time 1 to 29.5% at Time 3 (P<.001).

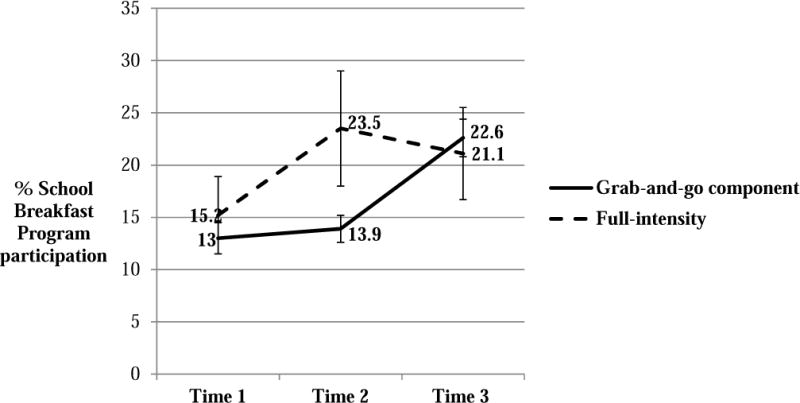

Treatment Intensity and School-level Changes in SBP Participation

Analyses addressing the third aim were designed to compare the impact of the grab-and-go component treatment to the impact of the full-intensity treatment. The interaction of time and treatment intensity group was statistically significant (P=.03). Results showed the full-intensity treatment was associated with a larger shift in school-level SBP participation between Time 1 and Time 2 as expected, but overall shifts from Time 1 to Time 3 were similar for the two treatment conditions at Time 3 (Figure 2). Mean school-level SBP participation for schools assigned to the full-intensity treatment increased from 15.2% at Time 1 to 21.1% at Time 3 (change: +5.9%). The positive shift in participation was similar to the increase in mean SBP participation for schools assigned to the grab-and-go component treatment (change: +9.6%). Evidence of fidelity to treatment, including the implementation of grab-and-go service and marketing and communication strategies, is described elsewhere.25

Figure 2.

School-level Average Percent School Breakfast Program Participation by Treatment Intensity and School Year of the Grab-and-Go Component of the Project BreakFAST Intervention in Rural Minnesota High Schools (N=16 schools; n=8 only grab-and-go component, n=8 full-intensity intervention)a,b,c,d

aTime 1 represents baseline participation among all incoming 9th and 10th grade students over one year prior to the intervention.

bTime 2 represents participation among 10th and 11th grade students during the implementation of the intervention (full-intensity) or the second baseline year of participation (grab-and-go).

cTime 3 represents participation among 11th and 12th grade students during the school year following implementation (full-intensity) or school year of implementation (grab-and-go).

dModel includes fixed effects of treatment intensity group, time, and their interaction along with wave assignment, percent of students eligible for free/reduced-price school meals, percent of students that identify as non-Hispanic white race, percent of students chronically absent, and percent of students in 10th grade.

DISCUSSION

This study described the impact of providing a grab-and-go service option on the SBP participation of rural high school students and examined whether the impact of this low-cost intervention was related to student characteristics. The results demonstrate that increasing access to the SBP and social support for eating breakfast are effective strategies for promoting student participation that offer great potential reach without great expense. The combination of these strategies was found to be similarly effective for students regardless of free/reduced-price school meal eligibility or ethnic/racial background. Additionally, the results demonstrate that low-cost interventions may have a similarly positive impact on SBP participation as more costly interventions that make use of professional marketing campaigns and intensive technical support for implementation. Although many lessons were learned in initially implementing the full-intensity treatment (e.g., identification of vendors with whole grain products, use of walkie talkies by grab-and-go cart staff) and the grab-and-go component treatment schools benefited from these lessons, the grab-and-go component treatment schools did not receive extensive support for implementation beyond the Project BreakFAST training. The evaluation results are among the first to quantifiably demonstrate the success of an intervention designed to improve SBP participation among high school students and may be useful to public health and school professionals seeking to build support for the implementation of similar strategies.22, 27

The current study findings build on other research that has primarily addressed the feasibility of expanded breakfast programs21–24 and associated changes in SBP participation22, 27–30 among students in lower grade levels. Previously reported common concerns regarding grab-and-go breakfast programs such as operating expenses, additional food waste, cleanliness, and student behavior problems may be barriers to implementation.21–24 Multiple studies have addressed these concerns by conducting process evaluations and documented conversations with school personnel that have guided strategies for overcoming these potential problems.21–24 For example, one pilot study involving personnel at suburban high schools reported that most participants felt students were respectful of the process; no additional waste or trash was created; and minimal time and work were associated with the changes.21 Similarly, another evaluation of a 9 am in-class nutrition break program reported that 74% of teachers at one urban high school perceived benefits in terms of student performance and motivation while only 35% had some concerns about messes created or the snack making students “hyper”.23 Just one previous impact evaluation study involving U.S. high school students was identified and found to quantify the positive changes in SBP participation that occurred following implementation of a grab-and-go breakfast cart program after the start of class at a suburban high school.22 This program for suburban students was launched in the fall and, by the end of the school year, average daily SBP participation had increased by more than 400%. The effect size reported by the impact evaluation among suburban students is not directly comparable to the results reported here as the previous study reported on percent increase in the total number of breakfast meals served per day and the current study examined change in the average of individual student participation for students enrolled at least 30 days of the school year. It possible the impact of serving breakfast after school begins would be greater for participation among rural versus urban students as students in rural areas often must travel a longer distance to school.31

Strengths and limitations of the current study should be considered in interpreting the findings. Strengths included the use of administrative data to assess SBP participation, the focus on adolescents enrolled at rural schools, and the unique opportunity to compare intervention formats. The collection of administrative data eliminated the need to rely on self-report of eating breakfast and the potential for recall bias. Further, administrative data importantly allowed for examining the impact of the intervention on SBP participation in each month of the school year and checking if weather-related or other seasonal obstacles to accessing alternative food sources played a role without overburdening participants with surveys. Nutrition and weight are priority areas for improving the health of rural youth and few interventions designed to improve eating behaviors have been evaluated in rural school settings.32 The delayed intervention design allowed for comparing the impact of a high-intensity treatment that included a professionally-developed marketing campaign and proactive technical support to the grab-and-go only component (without a professional marketing campaign or extensive staff support) among similar populations of rural secondary school students.

Despite the advantages of using administrative data to assess SBP participation, the reliance on administrative data did not allow for examining changes in the types of food and beverages consumed at breakfast, changes in the frequency of eating breakfast prepared at home or from other sources, or implications for overall dietary patterns. Few students self-reported getting breakfast prepared at a fast-food restaurant (4%) or convenience store (5%) more than once per week at baseline; however, getting breakfast this often from a vending machine or the school store was reported by 5% of students and getting breakfast at home was reported by more than half of students. The lack of data on changes in eating breakfast from other sources precluded further investigation of changes in overall weekly breakfast frequency and the likelihood of eating multiple breakfast meals on a given day. The Project BreakFAST study was also not designed with the intent to compare the impact of the full-intensity intervention to the impact of the grab-and-go component alone; consequently, no assessment of SBP participation was completed in the year following implementation of only the grab-and-go component. As post-intervention survey data was also not collected from students that received only the grab-and-go component, it was not possible to examine whether students experienced changes in their attitudes or beliefs around eating breakfast. Caution should be used in interpreting the comparisons between SBP participation at full-intensity intervention and grab-and-go component only schools as well as in making generalizations to youth from other areas. The data were collected in one region of a Midwest state and it is possible the intervention impact may depend in part on the local accessibility of retail food stores and restaurants as alternative sources for getting breakfast.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate the potential for grab-and-go breakfast programs to contribute to better nutrition and academic outcomes for adolescents. Grab-and-go programs can be feasibly implemented outside the context of a resource-intensive intervention and are likely to be effective without large expenditures for marketing. Previous research has demonstrated that skipping breakfast has a negative impact on overall dietary intake and academic achievement.1, 3 As prior work has also documented that skipping breakfast is highly and disproportionately prevalent among nutritionally vulnerable populations of school-age youth, the findings of the current study regarding the positive intervention impact for adolescents eligible for free/reduced-price school meals and of non-white race are particularly important.1 Public health and school professionals can use the results of this study in advocating for the implementation of programs designed to increase access to the SBP and social support for eating breakfast at school. Additionally, the findings suggest the significance of conducting research to investigate the impact of grab-and-go programs on overall energy intake and dietary quality to inform the potential need for strategy refinements. Despite the improvement in SBP participation associated with the grab-and-go intervention described here, the average percent participation after implementation was still low (22.6%) and there also remains a need for strategy refinements to further increase SBP participation. Next steps should specifically include investigating strategy refinements that may increase the relevance of grab-and-go programs for at-risk groups of students from low-income families and diverse ethnic/racial backgrounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Number R01HL113235 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Basch C. Breakfast and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81:635–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neil C, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Hayes D, Jana L, Klinger S, Stephenson-Martin S. The role of breakfast in health: definition and criteria for a quality breakfast. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:S8–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rampersaud G, Pereira M, Girard B, Adams J, Metzl J. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:743–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Sullivan T, Robinson M, Kendall G, et al. A good-quality breakfast is associated with better mental health in adolescence. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:249–258. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, Youth Online 2015 High School Results. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/results.htm. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- 6.McCormack L, Meendering J. Diet and physical activity in rural vs urban children and adolescents in the United States: a narrative review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson N, Story M. Barriers to equity in nutritional health for U.S. children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4:102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi C, Davey C, Nelson T, et al. Disparities persist in nutrition policies and practices in Minnesota secondary schools. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson J, Johnson A. Urban-rural differences in childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Obes. 2015;11:233–241. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Widome R, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P, Haines J, Story M. Eating when there is not enough to eat: eating behaviors and perceptions of food among food-insecure youths. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:822–828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan S, Pinckney R, Keeney D, Frankowski B, Carney J. Prevalence of food insecurity and utilization of food assistance program: an exploratory survey of a Vermont Middle School. J Sch Health. 2011;81:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grutzmacher S, Gross S. Household food security and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income fourth-graders. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt A, Hearst M, Wang Q, Nanney M. Food insecurity and rural adolescent personal health, home, and academic environments. J Sch Health. 2016;86:472–480. doi: 10.1111/josh.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food Research and Action Center. School breakfast scorecard: school year 2015–2016. http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/school-breakfast-scorecard-sy-2015–2016.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

- 15.Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Child and Adult Care Food Program: Meal Pattern Revisions Related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Fed Regist. 2016 Apr 25;81:24348–24383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hearst M, Shanafelt A, Wang Q, Leduc R, Nanney M. Barriers, benefits, and behaviors related to breakfast consumption among rural adolescents. J Sch Health. 2016;86:187–194. doi: 10.1111/josh.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweeney N, Horishita N. The breakfast-eating habits of inner city high school students. J Sch Nurs. 2005;21:100–105. doi: 10.1177/10598405050210020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.School Nutrition Association. Growing school breakfast participation. New ways to deliver breakfast to students on-the-go. 2011 https://schoolnutrition.org/Research/GrowingSchoolBreakfastParticipation/. Accessed July 21, 2017.

- 19.National Education Association Healthy Futures, No Kid Hungry Program, Share our Strength. Start school with breakfast: a guide to increasing school breakfast participation. Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food Research and Action Center. School breakfast: making it work in large school districts. Washington, DC: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haesly B, Nanney M, Coulter S, Fong S, Pratt R. Impact on staff of improving access to the school breakfast program: a qualitative study. J Sch Health. 2014;84:267–274. doi: 10.1111/josh.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsta J. Bringing breakfast to our students: a program to increase school breakfast participation. J Sch Nurs. 2013;29:263–270. doi: 10.1177/1059840513476094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeney N, Tucker J, Reynosa B, Glaser D. Reducing hunger-associated symptoms: the midmorning nutrition break. J Sch Nurs. 2006;22:32–39. doi: 10.1177/10598405060220010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conklin M, Bordi P. Middle school teachers’ perceptions of a “grab ‘n go” breakfast program. Top Clin Nutr. 2003;18:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nanney M, Leduc R, Hearst M, et al. Improving access to the School Breakfast Program increases participation among rural high school students. JAMA Pediatr. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanney M, Shanafelt A, Leduc R, et al. Project BreakFAST: Rationale, design, and recruitment and enrollment methods of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate an intervention to improve School Breakfast Program participation in rural high schools. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;3:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leatherdale S, Stefanczyk J, Kirkpatrick S. School breakfast-club program changes and youth eating breakfast during the school week in the COMPASS study. J Sch Health. 2016;86:568–577. doi: 10.1111/josh.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anzman-Frasca S, Carmichael Djang H, Halmo M, Dolan P, Economos C. Estimating impacts of a breakfast in the classroom program on school outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:71–77. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Wye G, Seoh H, Adjoian T, Dowell D. Evaluation of the New York City breakfast in the classroom program. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e59–e64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nanney M, Olaleye T, Wang Q, Motyka E, Klund-Schubert J. A pilot study to expand the school breakfast program in one middle school. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:436–442. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department US of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Travel to school: the distance factor NHTS Brief National Household Travel Survey. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolin J, Bellamy G. Rural Healthy People. 2020 https://sph.tamhsc.edu/srhrc/docs/rhp2020.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.