Abstract

Coenzyme Q (CoQ) is an essential component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and an antioxidant in plasma membranes and lipoproteins. It is endogenously produced in all cells by a highly regulated pathway that involves a mitochondrial multiprotein complex. Defects in either the structural and/or regulatory components of CoQ complex or in non-CoQ biosynthetic mitochondrial proteins can result in a decrease in CoQ concentration and/or an increase in oxidative stress. Besides CoQ10 deficiency syndrome and aging, there are chronic diseases in which lower levels of CoQ10 are detected in tissues and organs providing the hypothesis that CoQ10 supplementation could alleviate aging symptoms and/or retard the onset of these diseases. Here, we review the current knowledge of CoQ10 biosynthesis and primary CoQ10 deficiency syndrome, and have collected published results from clinical trials based on CoQ10 supplementation. There is evidence that supplementation positively affects mitochondrial deficiency syndrome and the symptoms of aging based mainly on improvements in bioenergetics. Cardiovascular disease and inflammation are alleviated by the antioxidant effect of CoQ10. There is a need for further studies and clinical trials involving a greater number of participants undergoing longer treatments in order to assess the benefits of CoQ10 treatment in metabolic syndrome and diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, kidney diseases, and human fertility.

Keywords: Coenzyme Q, aging, disease, mitochondria, antioxidant, CoQ deficiency

Introduction

Coenzyme Q (CoQ, ubiquinone) is a unique lipid-soluble antioxidant that is produced de novo in animals (Laredj et al., 2014). It is composed of a benzoquinone ring and a polyisoprenoid tail containing between 6 and 10 subunits that are species-specific and confers stability to the molecule inside the phospholipid bilayer. The isoprene chain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains six subunits (CoQ6), seven subunits are present in Crucianella maritima (CoQ7), eight in E. coli (CoQ8), nine and 10 in mice (CoQ9 and CoQ10), and 10 in humans (CoQ10).

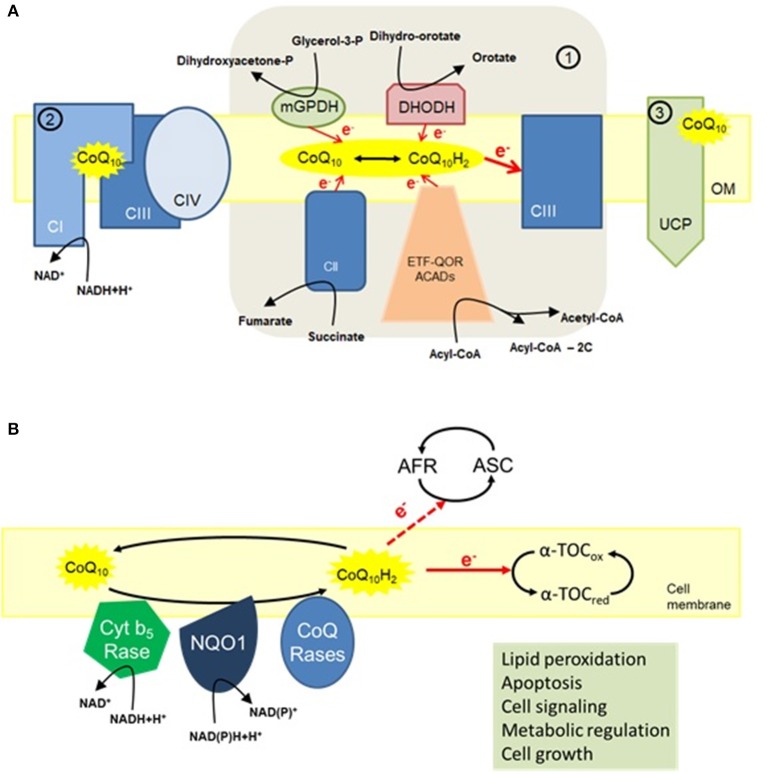

CoQ is a central component in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) located in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it transports electrons from complexes I and II to complex III to provide energy for proton translocation to the intermembrane space (López-Lluch et al., 2010). CoQ is also a structural component in complexes I and III and is essential in the stabilization of complex III in yeast (Santos-Ocana et al., 2002; Tocilescu et al., 2010). The ETC complexes are assembled into respiratory supercomplexes in order to function efficiently and prevent electron leakage to oxygen that ultimately results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Genova and Lenaz, 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Milenkovic et al., 2017). Mitochondrial CoQ may be associated in discrete pools dedicated to either NADH-coupled or FADH2-coupled electron transport (Lapuente-Brun et al., 2013). Complex I stability is determined by CoQ redox state (Guaras et al., 2016) and the reduced form of CoQ (CoQH2) directs complex I-specific ROS production to extend lifespan in Drosophila (Scialo et al., 2016). Mitochondrial activities such as the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, β-oxidation of fatty acids, and mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase contribute also to the increase in CoQH2 levels (Alcazar-Fabra et al., 2016) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The multiple functions of CoQ10. (A) Mitochondria. (1) The main function of CoQ10 in mitochondria is to transfer electrons to complex III (CIII). By transferring two electrons to CIII, the reduced form of CoQ10 (ubiquinol) is oxidized to ubiquinone. The pool of ubiquinol can be restored by accepting electrons either from members of the electron transport chain (CI and CII), glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) that use cytosolic electron donors, or from acyl-CoA dehydrogenases (ACADs); (2) CoQ10 is also a structural component of both CI and CIII and is associated with respiratory supercomplexes, especially the depicted supercomplex I+III+IV; (3) CoQ10 is an obligatory factor in proton transport by uncoupling proteins (UCPs) with concomitant regulation of mitochondrial activity (López-Lluch et al., 2010). (B) Cell membrane activities of CoQ10. Present in nearly all cellular membranes, CoQ10 offers antioxidant protection, in part, by maintaining the reduced state of α-tocopherol (α-TOC) and ascorbic acid (ASC). Furthermore, CoQ10 also regulates apoptosis by preventing lipid peroxidation. Other functions of CoQ10 in cell membrane include metabolic regulation, cell signaling, and cell growth through local regulation of cytosolic redox intermediates such as NAD(P)H (López-Lluch et al., 2010).

CoQ provides antioxidant protection to cell membranes and plasma lipoproteins (López-Lluch et al., 2010). By lowering lipid peroxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles that contributes to atherosclerosis (Thomas et al., 1997), CoQ treatment confers health benefits against cardiovascular diseases (Mortensen et al., 2014; Alehagen et al., 2016). The anti-oxidant function of CoQ is especially important in the plasma membrane by reducing vitamins C and E, and in preventing ceramide-mediated apoptosis (Navas et al., 2007), an important regulator of lifespan in the context of normal aging (De Cabo et al., 2004; López-Lluch et al., 2005; Martin-Montalvo et al., 2016) (Figure 1B). It has been proposed that NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) acts as a redox-sensitive switch to regulate the response of cells to changes in the redox environment (Ross and Siegel, 2017). The pharmacokinetics variability of the different compositions of CoQ10 may result in fairly different plasma concentration-time profiles after CoQ10 administration (Weis et al., 1994; Molyneux et al., 2004). Indeed, the major amount of orally supplemented CoQ10 is eliminated via feces, with only a fraction of ingested CoQ10 reaching the blood and ultimately the various tissues and organs (Bentinger et al., 2003).

For these reasons, CoQ appears suitable for use in the treatment of different diseases. Here, we present recent advances in CoQ10 treatment of human diseases and the slowing down of the aging process, and highlight new strategies aimed at delaying the progression of chronic diseases by CoQ10 supplementation.

CoQ10 biosynthesis pathway

CoQ10 biosynthesis pathway is initiated in the cytosol where the isoprene tail is made from the conversion of mevalonate, a key intermediate involved in the synthesis of cholesterol and dolichol and protein prenylation adducts (Trevisson et al., 2011). The end of the isoprene tail is formed by a cytosolic heterotetrameric protein complex encoded by PDSS1 and PDSS2 genes (COQ1) (Kawamukai, 2015). The quinone ring unit is also produced in the cytosol from tyrosine or phenylalanine and attached to the isoprene tail inside mitochondria through the activity of COQ2-encoded polyprenyl transferase (Laredj et al., 2014; Acosta et al., 2016). The benzoquinone ring is then modified in the inner mitochondrial membrane and this process involves at least 12 nuclear-encoded proteins (COQ) (Bentinger et al., 2010), which are required for the formation of a multiprotein complex known as “synthome” (He et al., 2014; Alcazar-Fabra et al., 2016; Floyd et al., 2016). The assembly and stabilization of the synthome is far from being understood as it may encompass yet to be discovered new interacting protein partners (Allan et al., 2015; Morgenstern et al., 2017). CoQ biosynthesis pathway is tightly regulated both at the transcriptional and translational levels (Turunen et al., 2000; Brea-Calvo et al., 2009; Cascajo et al., 2016) and by phosphorylation of some of the complex components (Martin-Montalvo et al., 2011, 2013; Guo et al., 2017; He et al., 2017).

CoQ10 deficiency syndrome

CoQ10 deficiencies are based on decreased CoQ10 levels and can be measured in skeletal muscle and/or skin fibroblast from patients suffering these rare (frequency less than 1:100000) inherited clinically and genetically heterogeneous diseases that impair oxidative phosphorylation and other mitochondrial functions (Desbats et al., 2015b; Acosta et al., 2016; Gorman et al., 2016; Rodriguez-Aguilera et al., 2017). CoQ10 deficiency can be caused by mutations in COQ genes that encode proteins of the CoQ biosynthesis pathway (primary deficiency) or as a secondary deficiency caused by defects in other mitochondrial functions that are indirectly involved in the biosynthesis of CoQ10 (Doimo et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Gorman et al., 2016; Yubero et al., 2016; Salviati et al., 2017).

Primary CoQ10 deficiency is characterized by highly heterogeneous clinical signs, with the severity and symptoms varying greatly as is the age of onset, which can be from birth to the seventh decade, and beyond (Salviati et al., 2017). Current clinical manifestations that may indicate primary CoQ10 deficiency are: (1) steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome without mutations in NPHS1 and/or NPHS2 genes particularly when associated with deafness, retinopathy, and other neurological defects; (2) mitochondrial encephalopathy including hypotonia, strokes, cerebellar ataxia, spasticity, peripheral neuropathy, and intellectual disability. These patients may also be presenting symptoms of myopathy, retinopathy, optic atrophy, sensorineural hearing loss, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; (3) unexplained ataxia particularly when family history suggests a recessive autosomal heritage; and (4) exercise intolerance appearing from 6 to 33 years of age, with muscular weakness and high serum creatine kinase.

Primary CoQ10 deficiencies are conditions where pathogenic mutations have occurred in genes involved in the biosynthesis of CoQ10 (Table 1). Mutations in PDSS2, COQ6, and ADCK4/COQ8B affect mainly the kidney by inducing steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome while COQ2 mutations induce multisystem disorders whose severity correlates with the mutated genotype (Desbats et al., 2016). Individuals affected by pathogenic mutations in the deduced amino acid sequence of COQ4, COQ7, COQ9, and/or PDSS1 develop encephalopathy and those affected by mutations in ADCK3/COQ8A develop mainly cerebellar disorders.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotypes caused by mutations in CoQ synthome and the effect of CoQ10 therapy in humans.

| Gene | N° of patients | Age of onset | Clinical phenotype | Effect of CoQ therapy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSS1 (COQ1) | 2 | 1−2 years | Encephalopathy, Peripheral neuropathy, Optic atrophy, Heart valvulopathy, Mild lactic acidosis, Overweight, Deafness, Moderate pulmonary artery hypertension, Mild mental retardation | No | Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| PDSS2 (COQ1) | 4 | ~3 months | Nephrotic syndrome, Leigh syndrome, Ataxia, Deafness, Retinopathy | Improvement | Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a,b; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| COQ2 | 17 | Birth, 3 weeks,~1 year, 18 month, Adolescence | Nephrotic syndrome, Encephalomyopathy, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, MELAS-like syndrome, Seizures, Retinopathy, Lactic acidosis, Deafness, Adult onset multisystem atrophy, Cerebellar atrophy, Myoclonus, Optic atrophy, Myopathy edema | Improvement | Jakobs et al., 2013; Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a,b; Gigante et al., 2017 |

| COQ4 | 1 | Birth | Encephalomyopathy, Weakness, Hypotonia, Intellectual disability, Seizures, Heart failure, Myopathy, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Myopathy, Dysmorphic features | Improvement | Salviati et al., 2012, 2017; Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Sondheimer et al., 2017 |

| COQ6 | 13 | 0.2–6 years | Nephrotic syndrome, Deafness, Encephalopathy, Seizures, Ataxia, Growth retardation, Facial dysmorphism | Improvement | Heeringa et al., 2011; Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| COQ7 | 1 | Birth | Encephalopathy, Intellectual disability, Peripheral neuropathy, Muscle weakness | Improvement | Freyer et al., 2015; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| ADCK3 (COQ8A) | 23 | 18 months, 1–2, 3–11, 15–18, 27 years | Cerebellar ataxia, Encephalopathy, Seizures, Dystonia, Spasticity, Migraine, Exercise intolerance, Myoclonus, Intellectual disability, Hypotonia, Muscle fragility, Feeding difficulties, Walking difficulty | Improvement | Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Barca et al., 2016; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| ADCK4 (COQ8B) | 15 | <1, 3–14, 16–21 years | Mental retardation, Nephrotic syndrome | Improvement | Ashraf et al., 2013; Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Salviati et al., 2017 |

| COQ9 | 1 | Birth | Encephalomyopathy, Renal tubulopathy, Cardiac hypertrophy, Seizures, Cerebellar atrophy, Myopathy | No | Laredj et al., 2014; Desbats et al., 2015a; Salviati et al., 2017 |

Abnormally low CoQ10 levels can be associated with mitochondrial pathologies caused by mutations in genes encoding components of the oxidative phosphorylation chain or of other cellular functions not directly associated with mitochondrial function (Yubero et al., 2016). Known as secondary CoQ10 deficiencies, these disorders could represent an adaptive mechanism to bioenergetic requirements. For example, secondary CoQ10 deficiency can appear in some patients with defects in glucose transport caused by GLUT1 mutations (Yubero et al., 2014). A group of patients with very severe neuropathies showed impaired CoQ10 synthesis, indicating the importance of CoQ10 homeostasis in human health (Asencio et al., 2016).

In individuals with primary CoQ10 deficiency, early treatment with high-dose oral CoQ10 supplementation improves the pathological phenotype, limits the progression of encephalopathy, and helps recover kidney damage (Montini et al., 2008). Onset of renal symptoms in PDSS2-deficient mice can be prevented with CoQ10 supplementation (Saiki et al., 2008). The European Medicine Agency (EMA) has recently approved ubiquinol—the reduced form of CoQ10 (CoQ10H2)—as an orphan drug for the treatment of primary CoQ10 deficiency (http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/o1765.htm). However, patients suffering from secondary CoQ10 deficiency may fail to respond to CoQ10 supplementation (Pineda et al., 2010).

CoQ10 and aging

A significant reduction in the rate of CoQ biosynthesis has been proposed to occur during the aging process and aging-associated diseases (Beyer et al., 1985; Kalen et al., 1989; Battino et al., 1995; Turunen et al., 1999). However, there are discrepancies about the relationship between the levels of CoQ and the progression of aging.

Mice lacking one of the alleles of the COQ7 gene (mCOQ7/mCLK1 gene) show extended longevity even though their CoQ levels are the same as wild-type mice, suggesting that a factor other than CoQ per se may be responsible for lifespan extension in these animals (Lapointe and Hekimi, 2008). However, other in vivo studies have reported a direct association between longevity and mitochondrial levels of CoQ in the Samp1 model of senescence-accelerated mice (Tian et al., 2014). Supplementation with ubiquinol has been shown to activate mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis (Schmelzer et al., 2010) and delay senescence (Tian et al., 2014).

The concentrations of CoQ10 in the plasma of elderly people are positively correlated with levels of physical activity and cholesterol concentrations (Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2014a,b), as well as with lower lipid oxidative damage. The antioxidant protection conferred by CoQ10 is associated with skeletal muscle performance during aging as evidenced by the fact that a high CoQ10H2/CoQ10 ratio is accompanied by an increase in muscle strength (Fischer et al., 2016). Conversely, a low CoQ10H2/CoQ10 ratio could be predictor of sarcopenia in humans. Older individuals given a combination of selenium and CoQ10 over a 4-year period reported an improvement in vitality, physical performance, and quality of life (Johansson et al., 2015). Furthermore, CoQ10 supplementation confers health benefits in elderly people by preventing chronic oxidative stress associated with cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases (Gonzalez-Guardia et al., 2015). Despite these evidences, more reliable clinical trials focusing on the elderly are needed before considering CoQ10 as an effective anti-aging therapy (Varela-Lopez et al., 2016).

CoQ10 supplementation in the treatment of human diseases

CoQ10 has been used in the treatment of a number of human pathologies and disorders. Clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have examined the safety and efficacy of CoQ10 in treating human diseases. With regards to safety, the highest dose for CoQ10 supplementation is 1200 mg daily according to well-designed randomized, controlled human trials, although doses as high as 3000 mg/day have been used in shorter clinical trials (Hathcock and Shao, 2006). CoQ is generally safe and well-tolerated in treating patients suffering from early-stage Huntington disease with 2400 mg/day of CoQ10 (McGarry et al., 2017).

As indicated below, prudence is needed when interpreting the results of several clinical trials. A combination of factors including the small number of trials, substantial differences that exist in the experimental designs, dose and duration of treatment, the number of patients enrolled, and the relative short follow-up periods contribute to apparent inconsistencies in the published data. Despite these limitations, CoQ10 can be considered as an important coadjuvant in the treatment of different diseases, especially in chronic conditions affecting the elderly.

Cardiovascular disease

The number of deaths attributed to heart failure is increasing worldwide and has become a global health issue. Heart failure is accompanied by increased ROS formation, which can be attenuated with antioxidants. A systematic review has recently examined the efficacy of CoQ10 supplementation in the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) without lifestyle intervention (Flowers et al., 2014). These authors interpreted the results to indicate a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure without improvements in other CVD risk factors, such as diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL- and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, and triglycerides. A second meta-analysis explored the impact of CoQ10 in the prevention of complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and the results showed that CoQ10 therapy lowers the need of inotropic drugs and reduces the appearance of ventricular arrhythmias after surgery (de Frutos et al., 2015).

Short-term daily treatment (12 weeks or less) with 100 mg CoQ10 improves left ventricular ejection fraction in patients suffering from heart failure (Fotino et al., 2013). In contrast, no effect of CoQ10 was observed on left ventricular ejection fraction or exercise capacity in patients with heart failure (Madmani et al., 2014). However, a 2-year treatment with CoQ10 (300 mg/day) as adjunctive therapy in a randomized, controlled multicenter trial affecting 420 patients suffering from chronic heart failure (Q-SYMBIO trial) demonstrated an improvement in symptoms and reduction in major cardiovascular events (Mortensen et al., 2014). A study on the effects of long-term treatment with CoQ10 (200 mg/day) plus selenium (200 μg as selenized yeast) in a homogeneous Swedish healthy elderly population (n = 219) revealed a significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality not only during the 4-year treatment period, but also 10 years later, compared to those taking either a placebo (n = 222) or were without treatment (n = 227) (Alehagen et al., 2015, 2016).

Metabolic syndrome and diabetes

CoQ10 has been proposed for the treatment of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes by virtue of its antioxidant properties. However, current results from clinical trials cannot conclusively determine the efficacy of CoQ10 because either of the missing information on the CoQ10 formulation used or the low number of trials and/or patients enrolled.

One effect attributable to CoQ10 therapy in type 2 diabetic patients (260 mg/day for 11 weeks) is its rather mild, but significant capacity to reduce fasting plasma glucose levels without changes in fasting insulin and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Moradi et al., 2016). However, analysis of more than seven trials involving 356 participants showed that CoQ10 supplementation for at least 12 weeks had no significant effects on glycemic control, lipid profile, or blood pressure in diabetic patients, but was able to reduce serum triglycerides levels (Suksomboon et al., 2015). In a follow-up analysis of data obtained from Q-SYMBIO clinical trials (Mortensen et al., 2014), Alehagen and colleagues were able to show that in elderly healthy participants who received selenium and CoQ10 supplementation for over 4 years, an increase in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and postprandial insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) levels, and greater age-corrected IGF-1 score based on the standard deviation of the mean value were observed compared with placebo-treated individuals (Alehagen et al., 2017).

Supplementation with CoQ10 has produced beneficial effects in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia by initiating changes in blood lipid concentration. A combination of CoQ10 with red yeast rice, berberina, policosanol, astaxanthin, and folic acid significantly decreased total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose in the blood while increasing HDL-cholesterol levels (Pirro et al., 2016). However, the impact of CoQ10 alone without the other supplements was not directly assessed. Nevertheless, there are reports to suggest that CoQ10 is very effective in reducing serum triglycerides levels (Suksomboon et al., 2015) and plasma lipoprotein(a) (Sahebkar et al., 2016). Chronic treatment with statins is associated with myopathy (Law and Rudnicka, 2006), a side-effect representing a broad clinical spectrum of disorders largely associated with a decrease in CoQ10 levels and selenoprotein activity (Thompson et al., 2003; Fedacko et al., 2013). Statins impair skeletal muscle and myocardial bioenergetics (Littarru and Langsjoen, 2007) via inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, a key enzyme in the mevalonate pathway implicated in cholesterol and CoQ biosynthesis, and reduction in mitochondrial complex III activity of the electron transport chain (Schirris et al., 2015). A total of 60 patients suffering from statin-associated myopathy were enrolled in a 3-month study to test for efficacy of CoQ10 and selenium treatment. A consistent reduction in their symptoms, including muscle pain, weakness, cramps, and fatigue was observed, suggesting an attenuation of the side-effects of chronic statin treatment following CoQ10 supplementation (Fedacko et al., 2013). In a previous study, however, 44 patients suffering from statin-induced myalgia saw no improvement in their conditions after receiving CoQ10 for 3 months (Young et al., 2007). Other studies have determined that CoQ10 supplementation improves endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients treated with statins (Hamilton et al., 2009) and can reverse the worsening of the diastolic function induced by statins (Silver et al., 2004).

Because of its capacity to reduce the side-effects of statins, CoQ10 has been proposed to prevent and/or slow the progression of frailty and sarcopenia in the elderly chronically treated with statins.

Kidney disease

Oxidative stress plays an essential role in diabetic kidney disease, and experiments performed on rats showed a promising protective effect of ubiquinol in the kidneys (Ishikawa et al., 2011). However, a meta-analysis study examining the efficiency of antioxidants on the initiation and progression of diabetic kidney disease revealed that antioxidants, including CoQ10, did not have reliable effects against this disease (Bolignano et al., 2017). Yet, in a recent clinical trial with 65 patients undergoing hemodialysis, supplementation with high amounts of CoQ10 (1200 mg/day) lowered F2-isoprostane plasma levels indicative of a reduction in oxidative stress (Rivara et al., 2017).

Inflammation

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are associated with many age-related diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and chronic kidney disease. A recent meta-analysis explored the efficacy of CoQ10 on the plasma levels of C-reactive protein, interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in patients afflicted with pathologies in which inflammation was a common factor including cardio-cerebral vascular disease, multiple sclerosis, obesity, renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and fatty liver disease (Fan et al., 2017). Administration of CoQ10 in doses ranging from 60 to 500 mg/day for a 1-week to 4-month intervention period significantly decreased production of inflammatory cytokines. The authors also surmised that CoQ10 supplementation decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines and inflammatory markers in the elderly with low CoQ10 levels (Fan et al., 2017).

Metabolic diseases, characterized by chronic, low grade inflammation, respond well to CoQ10 supplementation with significant decrease in TNF-α plasma levels without having an effect on C-reactive protein and IL-6 production (Zhai et al., 2017). Rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving CoQ10 (100 mg/day) for 2 months tended to have lower TFN-α plasma levels than placebo-treated patients (Abdollahzad et al., 2015). Another study reported that CoQ10 therapy in doses ranging from 60 to 300 mg/day caused no significant decrease in C-reactive protein while eliciting a significant reduction in IL-6 levels (Mazidi et al., 2017). More recently, CoQ10 has been found to markedly attenuate the elevated expression of inflammatory and thrombotic risk markers in monocytes of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, thereby improving endothelial function and mitochondrial activity in these patients (Perez-Sanchez et al., 2017).

A proinflammatory profile has also been associated with the progression of neurological symptoms in Down syndrome patients (Wilcock and Griffin, 2013). These patients have low CoQ10 plasma levels together with high plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α (Zaki et al., 2017). Supplementation with CoQ10 confers protection against the progression of oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in Down syndrome patients (Tiano and Busciglio, 2011; Tiano et al., 2011).

Neurodegenerative diseases

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been associated with the onset and/or development of neurodegenerative diseases (Arun et al., 2016; Bose and Beal, 2016; Grimm et al., 2016). Preclinical studies demonstrated that CoQ can preserve mitochondrial function and reduce the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the case of Parkinson's disease (Schulz and Beal, 1995). Experimental studies in animal models suggest that CoQ10 may protect against neuronal damage caused by ischemia, atherosclerosis, and toxic injury (Ishrat et al., 2006). Further, a screening for oxidative stress markers in patients with Parkinson's disease reported lower levels of CoQ10 and α-tocopherol and higher levels of lipoprotein oxidation in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid compared to non-affected individuals (Buhmann et al., 2004). Moreover, CoQ10 deficiency was observed at a higher frequency in Parkinson's disease, underscoring its utility as a peripheral biomarker (Mischley et al., 2012). For this reason, it has been suggested that CoQ10 supplementation could benefit patients suffering from neurodegenerative diseases.

Studies in humans have shown that CoQ10 is safe and well-tolerated even at high doses (1200–2400 mg/day) although its effect on reversing functional decline of mitochondria is unclear (Schulz and Beal, 1995; McGarry et al., 2017). Two reviews on recent clinical trials testing CoQ10 supplementation reported the lack of improvement in motor functions in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, which led the authors to conclude that the use of CoQ10 in these patients is unnecessary (Liu and Wang, 2014; Negida et al., 2016). However, other clinical trials in patients suffering from Parkinson's, Huntington's, and Friedreich's ataxia suggest that CoQ10 supplementation could delay functional decline, particularly with regard to Parkinson's disease (Beal, 2002; Shults, 2003). Indeed, four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies comparing CoQ10 treatment in 452 patients at early or mid-stage Parkinson's disease reported improvements in daily activities and other parameters (Liu et al., 2011). In contrast, a more recent multicenter randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial with CoQ10 in 609 patients with early-stage Huntington's disease did not slow the rate of patients' functional decline (McGarry et al., 2017). There is not enough evidence to indicate that CoQ10 supplementation can delay the progression of Huntington's disease, at least in its early stages.

Initiated in 2006, the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study evaluates the safety, tolerability, and impact of different antioxidants on biomarkers in this disease. There was no improvement observed in oxidative stress or neurodegeneration markers in a randomized clinical trial in Alzheimer's Disease patients with CoQ10 supplementation at a dose of 400 mg/day for 16 weeks (Galasko et al., 2012).

The role of plasma membrane CoQ10 in autism has been recently proposed (Crane et al., 2014). Patients with autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) exhibit higher proportions of mitochondrial dysfunctions than the general population (Rossignol and Frye, 2012), as evidenced by developmental regression, seizures, and elevated serum levels of lactate or pyruvate in ASD patients. Treatment with carnitine, CoQ10, and B-vitamins confers some improvements in ASD patients (Rossignol and Frye, 2012; Gvozdjakova et al., 2014).

Alleviation of symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis has been reported after supplementation with a combination of NADH and CoQ10 (Campagnolo et al., 2017); however, these authors suggest that nutritional supplements in the mitigation of the symptoms of this disease are not currently justifiable.

Human fertility

Male infertility has been associated with oxidative stress, and CoQ10 levels in seminal fluid is considered an important biomarker of healthy sperm (Gvozdjakova et al., 2015). Administration of CoQ10 improves semen parameters in the treatment of idiopathic male infertility (Arcaniolo et al., 2014). Additionally, CoQ10 supplementation (200–300 mg/day) in men with infertility improves sperm concentration, density, motility, and morphology (Safarinejad et al., 2012; Lafuente et al., 2013).

With regard to female infertility, the decrease in mitochondrial activity associated with CoQ10 deficiency probably affects the granulosa cells' capacity to generate ATP (Ben-Meir et al., 2015b). Indeed, reduction of CoQ10 levels in oocyte-specific PDSS2-deficient mice results in oocyte deficits and infertility (Ben-Meir et al., 2015a). Despite the absence of previous clinical trials that evaluate the effectiveness of CoQ10 supplementation in female infertility, these studies show promising results of this natural supplement in boosting female fertility during the prime reproductive period.

Concluding remarks

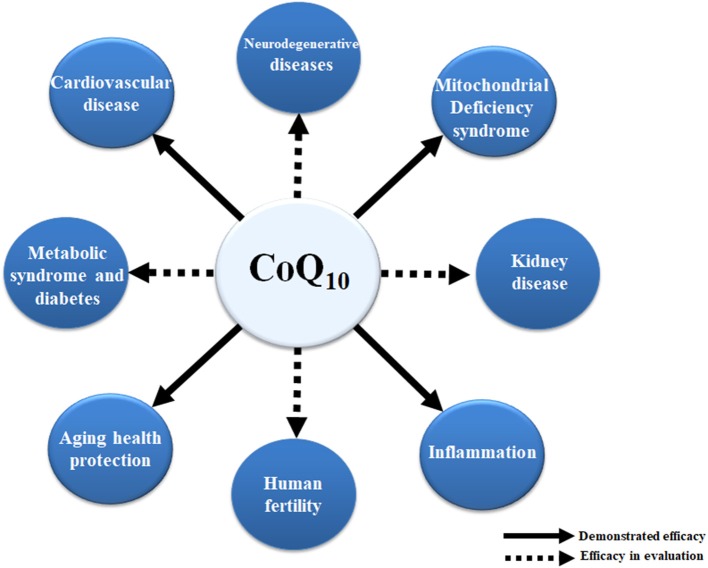

CoQ10 deficiency can be associated with a number of human diseases and age-related chronic conditions. In some cases, an unbalanced equilibrium between CoQ10 levels and/or functional ETC leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. In other cases, deficiency in CoQ10 and its associated antioxidative activity can significantly increase the level of oxidative damage. It seems clear that supplementation with CoQ10 improves mitochondrial function and confers antioxidant protection for organs and tissues affected by various pathophysiological conditions. The ability of CoQ10 to protect against the release of proinflammatory markers provides an attractive anti-inflammatory therapeutic for the treatment of some human diseases and in aging (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of CoQ10 in human diseases. The positive effect of CoQ10 has been already demonstrated in mitochondrial syndromes associated with CoQ10 deficiency, inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases as well as in the delay of some age-related processes. Dashed lines depict other positive effects of CoQ10 with regard to kidney disease, fertility, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases. However, more research is needed to validate these observations.

Following intraperitoneal administration of CoQ10 in rat, only small amount of the supplement reaches the kidney, muscle, and brain. Likewise, only a fraction of the orally administered CoQ10 reaches the blood while the major amount is eliminated via feces (Bentinger et al., 2003). The absoption of CoQ10 is slow and limited due to its hydrophobicity and large molecular weight and, therefore, high doses are needed to reach a number of rat tissues (e.g., muscle and brain) (Bhagavan and Chopra, 2006) and we can only assume that this also happens in humans. The pharmacokinetics variability of the different compositions of CoQ10 (Weis et al., 1994; Molyneux et al., 2004) may result in fairly different plasma concentration-time profiles after CoQ10 administration in the treatment of various diseases and monitoring of clinical effects.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have revealed that there are few randomized clinical trials on the effect of CoQ10 in combatting disease progression and improving quality of life. The results of these trials have been inconsistent likely due to varied dosages, small sample size, and short follow-up periods. More studies performed on humans in focused trials are needed in order to understand the promising effects of CoQ10.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work has been partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), FIS PI14-01962, and the Andalusian Government grant BIO177 (FEDER funds of European Commission). JH-C has been awarded by CIBERER, Instituto de Salud Carlos III. This work was also supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

References

- Abdollahzad H., Aghdashi M. A., Asghari Jafarabadi M., Alipour B. (2015). Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-6) and oxidative stress in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Med. Res. 46, 527–533. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta M. J., Vazquez Fonseca L., Desbats M. A., Cerqua C., Zordan R., Trevisson E., et al. (2016). Coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1079–1085. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcazar-Fabra M., Navas P., Brea-Calvo G. (2016). Coenzyme Q biosynthesis and its role in the respiratory chain structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1857, 1073–1078. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alehagen U., Aaseth J., Johansson P. (2015). Reduced cardiovascular mortality 10 years after supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 for four years: follow-up results of a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in elderly citizens. PLoS ONE 10:e0141641. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alehagen U., Alexander J., Aaseth J. (2016). Supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 reduces cardiovascular mortality in elderly with low selenium status. A secondary analysis of a randomised clinical trial. PLoS ONE 11:e0157541. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alehagen U., Johansson P., Aaseth J., Alexander J., Brismar K. (2017). Increase in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 after supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10. A prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial among elderly Swedish citizens. PLoS ONE 12:e0178614. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan C. M., Awad A. M., Johnson J. S., Shirasaki D. I., Wang C., Blaby-Haas C. E., et al. (2015). Identification of Coq11, a new coenzyme Q biosynthetic protein in the CoQ-synthome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 7517–7534. 10.1074/jbc.M114.633131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcaniolo D., Favilla V., Tiscione D., Pisano F., Bozzini G., Creta M., et al. (2014). Is there a place for nutritional supplements in the treatment of idiopathic male infertility? Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 86, 164–170. 10.4081/aiua.2014.3.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arun S., Liu L., Donmez G. (2016). Mitochondrial biology and neurological diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 143–154. 10.2174/1570159X13666150703154541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asencio C., Rodriguez-Hernandez M. A., Briones P., Montoya J., Cortes A., Emperador S., et al. (2016). Severe encephalopathy associated to pyruvate dehydrogenase mutations and unbalanced coenzyme Q10 content. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 24, 367–372. 10.1038/ejhg.2015.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S., Gee H. Y., Woerner S., Xie L. X., Vega-Warner V., Lovric S., et al. (2013). ADCK4 mutations promote steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome through CoQ10 biosynthesis disruption. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 5179–5189. 10.1172/JCI69000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barca E., Musumeci O., Montagnese F., Marino S., Granata F., Nunnari D., et al. (2016). Cerebellar ataxia and severe muscle CoQ10 deficiency in a patient with a novel mutation in ADCK3. Clin. Genet. 90, 156–160. 10.1111/cge.12742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battino M., Gorini A., Villa R. F., Genova M. L., Bovina C., Sassi S., et al. (1995). Coenzyme Q content in synaptic and non-synaptic mitochondria from different brain regions in the ageing rat. Mech. Ageing Dev. 78, 173–187. 10.1016/0047-6374(94)01535-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal M. F. (2002). Coenzyme Q10 as a possible treatment for neurodegenerative diseases. Free Radic. Res. 36, 455–460. 10.1080/10715760290021315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Meir A., Burstein E., Borrego-Alvarez A., Chong J., Wong E., Yavorska T., et al. (2015a). Coenzyme Q10 restores oocyte mitochondrial function and fertility during reproductive aging. Aging Cell 14, 887–895. 10.1111/acel.12368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Meir A., Yahalomi S., Moshe B., Shufaro Y., Reubinoff B., Saada A. (2015b). Coenzyme Q-dependent mitochondrial respiratory chain activity in granulosa cells is reduced with aging. Fertil. Steril. 104, 724–727. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M., Dallner G., Choknacki T., Swiezewska E. (2003). Distrinution and breakdown of labeled coenzyme Q10 in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 563–575. 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01357-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M., Tekle M., Dallner G. (2010). Coenzyme Q–biosynthesis and functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396, 74–79. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer R. E., Burnett B. A., Cartwright K. J., Edington D. W., Falzon M. J., Kreitman K. R., et al. (1985). Tissue coenzyme Q (ubiquinone) and protein concentrations over the life span of the laboratory rat. Mech. Ageing Dev. 32, 267–281. 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90085-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavan H. N., Chopra R. K. (2006). Coenzyme Q10: absortion, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Free Radic. Res. 40, 445–453. 10.1080/10715760600617843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolignano D., Cernaro V., Gembillo G., Baggetta R., Buemi M., D'arrigo G. (2017). Antioxidant agents for delaying diabetic kidney disease progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12:e0178699. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A., Beal M. F. (2016). Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 139(Suppl. 1), 216–231. 10.1111/jnc.13731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brea-Calvo G., Siendones E., Sanchez-Alcazar J. A., De Cabo R., Navas P. (2009). Cell survival from chemotherapy depends on NF-kappaB transcriptional up-regulation of coenzyme Q biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 4:e5301. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann C., Arlt S., Kontush A., Moller-Bertram T., Sperber S., Oechsner M., et al. (2004). Plasma and CSF markers of oxidative stress are increased in Parkinson's disease and influenced by antiparkinsonian medication. Neurobiol. Dis. 15, 160–170. 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo N., Johnston S., Collatz A., Staines D., Marshall-Gradisnik S. (2017). Dietary and nutrition interventions for the therapeutic treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 30, 247–259. 10.1111/jhn.12435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascajo M. V., Abdelmohsen K., Noh J. H., Fernandez-Ayala D. J., Willers I. M., Brea G., et al. (2016). RNA-binding proteins regulate cell respiration and coenzyme Q biosynthesis by post-transcriptional regulation of COQ7. RNA Biol. 13, 622–634. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1119366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane F. L., Low H., Sun I., Navas P., Gvozdjakova A. (2014). Plasma membrane coenzyme Q: evidence for a role in autism. Biologics 8, 199–205. 10.2147/BTT.S53375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cabo R., Cabello R., Rios M., López-Lluch G., Ingram D. K., Lane M. A., et al. (2004). Calorie restriction attenuates age-related alterations in the plasma membrane antioxidant system in rat liver. Exp. Gerontol. 39, 297–304. 10.1016/j.exger.2003.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frutos F., Gea A., Hernandez-Estefania R., Rabago G. (2015). Prophylactic treatment with coenzyme Q10 in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: could an antioxidant reduce complications? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 20, 254–259. 10.1093/icvts/ivu334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo-Cruz J., Rodriguez-Bies E., Ballesteros-Simarro M., Navas-Enamorado I., Tung B. T., Navas P., et al. (2014a). Physical activity affects plasma coenzyme Q10 levels differently in young and old humans. Biogerontology 15, 199–211. 10.1007/s10522-013-9491-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo-Cruz J., Rodriguez-Bies E., Navas-Enamorado I., Del Pozo-Cruz B., Navas P., López-Lluch G. (2014b). Relationship between functional capacity and body mass index with plasma coenzyme Q10 and oxidative damage in community-dwelling elderly-people. Exp. Gerontol. 52, 46–54. 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbats M. A., Lunardi G., Doimo M., Trevisson E., Salviati L. (2015a). Genetic bases and clinical manifestations of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ 10) deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 38, 145–156. 10.1007/s10545-014-9749-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbats M. A., Morbidoni V., Silic-Benussi M., Doimo M., Ciminale V., Cassina M., et al. (2016). The COQ2 genotype predicts the severity of coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 4256–4265. 10.1093/hmg/ddw257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbats M. A., Vetro A., Limongelli I., Lunardi G., Casarin A., Doimo M., et al. (2015b). Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency presenting as fatal neonatal multiorgan failure. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23, 1254–1258. 10.1038/ejhg.2014.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doimo M., Desbats M. A., Cerqua C., Cassina M., Trevisson E., Salviati L. (2014). Genetics of coenzyme q10 deficiency. Mol. Syndromol. 5, 156–162. 10.1159/000362826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L., Feng Y., Chen G. C., Qin L. Q., Fu C. L., Chen L. H. (2017). Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 119, 128–136. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedacko J., Pella D., Fedackova P., Hanninen O., Tuomainen P., Jarcuska P., et al. (2013). Coenzyme Q(10) and selenium in statin-associated myopathy treatment. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 91, 165–170. 10.1139/cjpp-2012-0118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Onur S., Niklowitz P., Menke T., Laudes M., Rimbach G., et al. (2016). Coenzyme Q10 status as a determinant of muscular strength in two independent cohorts. PLoS ONE 11:e0167124. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers N., Hartley L., Todkill D., Stranges S., Rees K. (2014). Co-enzyme Q10 supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD010405. 10.1002/14651858.CD010405.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd B. J., Wilkerson E. M., Veling M. T., Minogue C. E., Xia C., Beebe E. T., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial protein interaction mapping identifies regulators of respiratory chain function. Mol. Cell 63, 621–632. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotino A. D., Thompson-Paul A. M., Bazzano L. A. (2013). Effect of coenzyme Q(1)(0) supplementation on heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 268–275. 10.3945/ajcn.112.040741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyer C., Stranneheim H., Naess K., Mourier A., Felser A., Maffezzini C., et al. (2015). Rescue of primary ubiquinone deficiency due to a novel COQ7 defect using 2,4-dihydroxybensoic acid. J. Med. Genet. 52, 779–783. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-102986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D. R., Peskind E., Clark C. M., Quinn J. F., Ringman J. M., Jicha G. A., et al. (2012). Antioxidants for Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measures. Arch. Neurol. 69, 836–841. 10.1001/archneurol.2012.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova M. L., Lenaz G. (2014). Functional role of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 427–443. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante M., Diella S., Santangelo L., Trevisson E., Acosta M. J., Amatruda M., et al. (2017). Further phenotypic heterogeneity of CoQ10 deficiency associated with steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome and novel COQ2 and COQ6 variants. Clin. Genet. 92, 224–226. 10.1111/cge.12960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guardia L., Yubero-Serrano E. M., Delgado-Lista J., Perez-Martinez P., Garcia-Rios A., Marin C., et al. (2015). Effects of the Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme q10 on metabolomic profiles in elderly men and women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 70, 78–84. 10.1093/gerona/glu098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman G. S., Chinnery P. F., Dimauro S., Hirano M., Koga Y., Mcfarland R., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2:16080. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm A., Friedland K., Eckert A. (2016). Mitochondrial dysfunction: the missing link between aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Biogerontology 17, 281–296. 10.1007/s10522-015-9618-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaras A., Perales-Clemente E., Calvo E., Acin-Perez R., Loureiro-Lopez M., Pujol C., et al. (2016). The CoQH2/CoQ ratio serves as a sensor of respiratory chain efficiency. Cell Rep. 15, 197–209. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R., Zong S., Wu M., Gu J., Yang M. (2017). Architecture of human mitochondrial respiratory megacomplex I2III2IV2. Cell 170, 1247 e1212–1257 e1212. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdjakova A., Kucharska J., Dubravicky J., Mojto V., Singh R. B. (2015). Coenzyme Q(1)(0), alpha-tocopherol, and oxidative stress could be important metabolic biomarkers of male infertility. Dis. Markers 2015:827941 10.1155/2015/827941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdjakova A., Kucharska J., Ostatnikova D., Babinska K., Nakladal D., Crane F. L. (2014). Ubiquinol improves symptoms in children with autism. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014:798957. 10.1155/2014/798957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S. J., Chew G. T., Watts G. F. (2009). Coenzyme Q10 improves endothelial dysfunction in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 32, 810–812. 10.2337/dc08-1736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathcock J. N., Shao A. (2006). Risk assessment for coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 45, 282–288. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C. H., Black D. S., Allan C. M., Meunier B., Rahman S., Clarke C. F. (2017). Human COQ9 rescues a coq9 yeast mutant by enhancing coenzyme Q biosynthesis from 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and stabilizing the CoQ-synthome. Front. Physiol. 8:463. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C. H., Xie L. X., Allan C. M., Tran U. C., Clarke C. F. (2014). Coenzyme Q supplementation or over-expression of the yeast Coq8 putative kinase stabilizes multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complexes in yeast coq null mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 630–644. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa S. F., Chernin G., Chaki M., Zhou W., Sloan A. J., Ji Z., et al. (2011). COQ6 mutations in human patients produce nephrotic syndrome with sensorineural deafness. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2013–2024. 10.1172/JCI45693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A., Kawarazaki H., Ando K., Fujita M., Fujita T., Homma Y. (2011). Renal preservation effect of ubiquinol, the reduced form of coenzyme Q10. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 15, 30–33. 10.1007/s10157-010-0350-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishrat T., Khan M. B., Hoda M. N., Yousuf S., Ahmad M., Ansari M. A., et al. (2006). Coenzyme Q10 modulates cognitive impairment against intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 171, 9–16. 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs B. S., Van Den Heuvel L. P., Smeets R. J., De Vries M. C., Hien S., Schaible T., et al. (2013). A novel mutation in COQ2 leading to fatal infantile multisystem disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 326, 24–28. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P., Dahlstrom O., Dahlstrom U., Alehagen U. (2015). Improved health-related quality of life, and more days out of hospital with supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 combined. Results from a double blind, placebo-controlled prospective study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 19, 870–877. 10.1007/s12603-015-0509-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalen A., Appelkvist E. L., Dallner G. (1989). Age-related changes in the lipid compositions of rat and human tissues. Lipids 24, 579–584. 10.1007/BF02535072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamukai M. (2015). Biosynthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 80, 23–33. 10.1080/09168451.2015.1065172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente R., Gonzalez-Comadran M., Sola I., Lopez G., Brassesco M., Carreras R., et al. (2013). Coenzyme Q10 and male infertility: a meta-analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 30, 1147–1156. 10.1007/s10815-013-0047-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J., Hekimi S. (2008). Early mitochondrial dysfunction in long-lived Mclk1+/- mice. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26217–26227. 10.1074/jbc.M803287200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuente-Brun E., Moreno-Loshuertos R., Acin-Perez R., Latorre-Pellicer A., Colas C., Balsa E., et al. (2013). Supercomplex assembly determines electron flux in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Science 340, 1567–1570. 10.1126/science.1230381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laredj L. N., Licitra F., Puccio H. M. (2014). The molecular genetics of coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochimie 100, 78–87. 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Rudnicka A. R. (2006). Statin safety: a systematic review. Am. J. Cardiol. 97, 52C–60C. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littarru G. P., Langsjoen P. (2007). Coenzyme Q10 and statins: biochemical and clinical implications. Mitochondrion 7(Suppl.), S168–S174. 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang L. N. (2014). Mitochondrial enhancement for neurodegenerative movement disorders: a systematic review of trials involving creatine, coenzyme Q10, idebenone and mitoquinone. CNS Drugs 28, 63–68. 10.1007/s40263-013-0124-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang L., Zhan S. Y., Xia Y. (2011). Coenzyme Q10 for Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD008150. 10.1002/14651858.CD008150.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Lluch G., Rios M., Lane M. A., Navas P., De Cabo R. (2005). Mouse liver plasma membrane redox system activity is altered by aging and modulated by calorie restriction. Age 27, 153–160. 10.1007/s11357-005-2726-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Lluch G., Rodriguez-Aguilera J. C., Santos-Ocana C., Navas P. (2010). Is coenzyme Q a key factor in aging? Mech. Ageing Dev. 131, 225–235. 10.1016/j.mad.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madmani M. E., Yusuf Solaiman A., Tamr Agha K., Madmani Y., Shahrour Y., Essali A., et al. (2014). Coenzyme Q10 for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD008684. 10.1002/14651858.CD008684.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Montalvo A., Gonzalez-Mariscal I., Padilla S., Ballesteros M., Brautigan D. L., Navas P., et al. (2011). Respiratory-induced coenzyme Q biosynthesis is regulated by a phosphorylation cycle of Cat5p/Coq7p. Biochem. J. 440, 107–114. 10.1042/BJ20101422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Montalvo A., Gonzalez-Mariscal I., Pomares-Viciana T., Padilla-Lopez S., Ballesteros M., Vazquez-Fonseca L., et al. (2013). The phosphatase Ptc7 induces coenzyme Q biosynthesis by activating the hydroxylase Coq7 in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28126–28137. 10.1074/jbc.M113.474494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Montalvo A., Sun Y., Diaz-Ruiz A., Ali A., Gutierrez V., Palacios H. H., et al. (2016). Cytochrome b5 reductase and the control of lipid metabolism and healthspan. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2:16006. 10.1038/npjamd.2016.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazidi M., Kengne A. P., Banach M., Lipid, Blood Pressure Meta-Analysis Collaboration, G. (2017). Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on plasma C-reactive protein concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry A., McDermott M., Kieburtz K., De Blieck E. A., Beal F., Marder K., et al. (2017). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of coenzyme Q10 in Huntington disease. Neurology 88, 152–159. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic D., Blaza J. N., Larsson N. G., Hirst J. (2017). The enigma of the respiratory chain supercomplex. Cell Metab. 25, 765–776. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischley L. K., Allen J., Bradley R. (2012). Coenzyme Q10 deficiency in patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 318, 72–75. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux S., Florkowski C., Lever M., George P. (2004). The bioavailability of coenzyme Q10 supplements available in New Zealand differs markedly. N. Z. Med. J. 117, U1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini G., Malaventura C., Salviati L. (2008). Early coenzyme Q10 supplementation in primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2849–2850. 10.1056/NEJMc0800582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi M., Haghighatdoost F., Feizi A., Larijani B., Azadbakht L. (2016). Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on diabetes biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch. Iran. Med. 19, 588–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Stiller S. B., Lubbert P., Peikert C. D., Dannenmaier S., Drepper F., et al. (2017). Definition of a high-confidence mitochondrial proteome at quantitative scale. Cell Rep. 19, 2836–2852. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen S. A., Rosenfeldt F., Kumar A., Dolliner P., Filipiak K. J., Pella D., et al. (2014). The effect of coenzyme Q10 on morbidity and mortality in chronic heart failure: results from Q-SYMBIO: a randomized double-blind trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2, 641–649. 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas P., Villalba J. M., De Cabo R. (2007). The importance of plasma membrane coenzyme Q in aging and stress responses. Mitochondrion 7(Suppl.), S34–S40. 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negida A., Menshawy A., El Ashal G., Elfouly Y., Hani Y., Hegazy Y., et al. (2016). Coenzyme Q10 for patients with parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 15, 45–53. 10.2174/1871527314666150821103306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sanchez C., Aguirre M. A., Ruiz-Limon P., Abalos-Aguilera M. C., Jimenez-Gomez Y., Arias-De La Rosa I., et al. (2017). Ubiquinol effects on antiphospholipid syndrome prothrombotic profile: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37, 1923–1932. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda M., Montero R., Aracil A., O'callaghan M. M., Mas A., Espinos C., et al. (2010). Coenzyme Q(10)-responsive ataxia: 2-year-treatment follow-up. Mov. Disord. 25, 1262–1268. 10.1002/mds.23129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirro M., Mannarino M. R., Bianconi V., Simental-Mendia L. E., Bagaglia F., Mannarino E., et al. (2016). The effects of a nutraceutical combination on plasma lipids and glucose: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 110, 76–88. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara M. B., Yeung C. K., Robinson-Cohen C., Phillips B. R., Ruzinski J., Rock D., et al. (2017). Effect of coenzyme Q10 on biomarkers of oxidative stress and cardiac function in hemodialysis patients: the CoQ10 biomarker trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 69, 389–399. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Aguilera J. C., Cortes A. B., Fernandez-Ayala D. J., Navas P. (2017). Biochemical assessment of coenzyme Q10 deficiency. J. Clin. Med. 6:E27. 10.3390/jcm6030027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D., Siegel D. (2017). Functions of NQO1 in cellular protection and CoQ10 metabolism and its potential role as a redox sensitive molecular switch. Front. Physiol. 8:595. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol D. A., Frye R. E. (2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 290–314. 10.1038/mp.2010.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad M. R., Safarinejad S., Shafiei N., Safarinejad S. (2012). Effects of the reduced form of coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) on semen parameters in men with idiopathic infertility: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized study. J. Urol. 188, 526–531. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.03.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahebkar A., Simental-Mendia L. E., Stefanutti C., Pirro M. (2016). Supplementation with coenzyme Q10 reduces plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations but not other lipid indices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 105, 198–209. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki R., Lunceford A. L., Shi Y., Marbois B., King R., Pachuski J., et al. (2008). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation rescues renal disease in Pdss2kd/kd mice with mutations in prenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F1535–F1544. 10.1152/ajprenal.90445.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati L., Trevisson E., Doimo M., Navas P. (2017). Primary Coenzyme Q10 Deficiency, in GeneReviews(R), eds Pagon R. A., Adam M. P., Ardinger H. H., Wallace S. E., Amemiya A., Bean L. J. H., et al. (Seattle, WA: University of Washington; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati L., Trevisson E., Rodriguez Hernandez M. A., Casarin A., Pertegato V., Doimo M., et al. (2012). Haploinsufficiency of COQ4 causes coenzyme Q10 deficiency. J. Med. Genet. 49, 187–191. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Ocana C., Do T. Q., Padilla S., Navas P., Clarke C. F. (2002). Uptake of exogenous coenzyme Q and transport to mitochondria is required for bc1 complex stability in yeast coq mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10973–10981. 10.1074/jbc.M112222200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirris T. J., Renkema G. H., Ritschel T., Voermans N. C., Bilos A., Van Engelen B. G., et al. (2015). Statin-induced myopathy is associated with mitochondrial complex III inhibition. Cell Metab. 22, 399–407. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer C., Kubo H., Mori M., Sawashita J., Kitano M., Hosoe K., et al. (2010). Supplementation with the reduced form of Coenzyme Q10 decelerates phenotypic characteristics of senescence and induces a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha gene expression signature in SAMP1 mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 54, 805–815. 10.1002/mnfr.200900155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz J. B., Beal M. F. (1995). Neuroprotective effects of free radical scavengers and energy repletion in animal models of neurodegenerative disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 765, 100–110. discussion: 116–108. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb16565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scialo F., Sriram A., Fernandez-Ayala D., Gubina N., Lohmus M., Nelson G., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial ROS produced via reverse electron transport extend animal lifespan. Cell Metab. 23, 725–734. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shults C. W. (2003). Coenzyme Q10 in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 1917–1921. 10.2174/0929867033456882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver M. A., Langsjoen P. H., Szabo S., Patil H., Zelinger A. (2004). Effect of atorvastatin on left ventricular diastolic function and ability of coenzyme Q10 to reverse that dysfunction. Am. J. Cardiol. 94, 1306–1310. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer N., Hewson S., Cameron J. M., Somers G. R., Broadbent J. D., Ziosi M., et al. (2017). Novel recessive mutations in COQ4 cause severe infantile cardiomyopathy and encephalopathy associated with CoQ10 deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 12, 23–27. 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suksomboon N., Poolsup N., Juanak N. (2015). Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on metabolic profile in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 40, 413–418. 10.1111/jcpt.12280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. R., Neuzil J., Stocker R. (1997). Inhibition of LDL oxidation by ubiquinol-10. A protective mechanism for coenzyme Q in atherogenesis? Mol. Aspects Med. 18(Suppl.), S85–S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson P. D., Clarkson P., Karas R. H. (2003). Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 289, 1681–1690. 10.1001/jama.289.13.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G., Sawashita J., Kubo H., Nishio S. Y., Hashimoto S., Suzuki N., et al. (2014). Ubiquinol-10 supplementation activates mitochondria functions to decelerate senescence in senescence-accelerated mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 2606–2620. 10.1089/ars.2013.5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiano L., Busciglio J. (2011). Mitochondrial dysfunction and Down's syndrome: is there a role for coenzyme Q(10) ? Biofactors 37, 386–392. 10.1002/biof.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiano L., Carnevali P., Padella L., Santoro L., Principi F., Bruge F., et al. (2011). Effect of coenzyme Q10 in mitigating oxidative DNA damage in Down syndrome patients, a double blind randomized controlled trial. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 2103–2105. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocilescu M. A., Zickermann V., Zwicker K., Brandt U. (2010). Quinone binding and reduction by respiratory complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1797, 1883–1890. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisson E., Dimauro S., Navas P., Salviati L. (2011). Coenzyme Q deficiency in muscle. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 24, 449–456. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834ab528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M., Appelkvist E. L., Sindelar P., Dallner G. (1999). Blood concentration of coenzyme Q(10) increases in rats when esterified forms are administered. J. Nutr. 129, 2113–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M., Peters J. M., Gonzalez F. J., Schedin S., Dallner G. (2000). Influence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha on ubiquinone biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 607–614. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela-Lopez A., Giampieri F., Battino M., Quiles J. L. (2016). Coenzyme Q and its role in the dietary therapy against aging. Molecules 21:373. 10.3390/molecules21030373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M., Mortensen S. A., Rassing M. R., Moller-Sonnergaard J., Poulsen G., Rasmussen S. N. (1994). Bioavailability of four oral coenzyme Q10 formulations in healthy volunteers. Mol. Aspects Med. 15(Suppl.), s273–s280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock D. M., Griffin W. S. (2013). Down's syndrome, neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer neuropathogenesis. J. Neuroinflammation 10:84. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. M., Florkowski C. M., Molyneux S. L., Mcewan R. G., Frampton C. M., George P. M., et al. (2007). Effect of coenzyme Q(10) supplementation on simvastatin-induced myalgia. Am. J. Cardiol. 100, 1400–1403. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yubero D., Montero R., Martin M. A., Montoya J., Ribes A., Grazina M., et al. (2016). Secondary coenzyme Q10 deficiencies in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and non-OXPHOS disorders. Mitochondrion 30, 51–58. 10.1016/j.mito.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yubero D., O'callaghan M., Montero R., Ormazabal A., Armstrong J., Espinos C., et al. (2014). Association between coenzyme Q10 and glucose transporter (GLUT1) deficiency. BMC Pediatr. 14:284. 10.1186/s12887-014-0284-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki M. E., El-Bassyouni H. T., Tosson A. M., Youness E., Hussein J. (2017). Coenzyme Q10 and pro-inflammatory markers in children with Down syndrome: clinical and biochemical aspects. J. Pediatr). 93, 100–104. 10.1016/j.jped.2016.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J., Bo Y., Lu Y., Liu C., Zhang L. (2017). Effects of coenzyme Q10 on markers of inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12:e0170172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]