Abstract

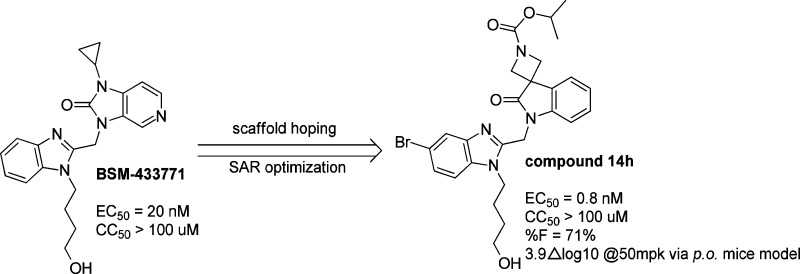

A new series of 3,3′-spirocyclic-2-oxo-indoline derivatives was synthesized and evaluated against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in a cell-based assay and animal model. Extensive structure–activity relationship study led to a lead compound 14h, which exhibited excellent in vitro potency with an EC50 value of 0.8 nM and demonstrated 71% oral bioavailability in mice. In a mouse challenge model of RVS infection, 14h demonstrated superior efficacy with a 3.9log RSV virus load reduction in the lung following an oral dose of 50 mg/kg.

Keywords: RSV, fusion inhibitor, benzimidazole

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a major cause of pneumonia and bronchiolitis in young children, immunocompromised adults, and the elderly, resulting in ∼125,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States.1,2 However, the treatment of RSV lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is limited.3 Synagis (Palivizumab), a marketed humanized monoclonal antibody targeting fusion glycoprotein (F protein) of RSV, was licensed for passive prophylaxis intervention in high-risk infants. However, its high cost of treatment and relatively low protection to high-risk children limit its usage. An aerosol formulation of Ribavirin (Virazole) is the only chemotherapeutic agent on the market. Virazole is not a specific protection for young children and is rarely used due to its variable efficacy and toxicity.

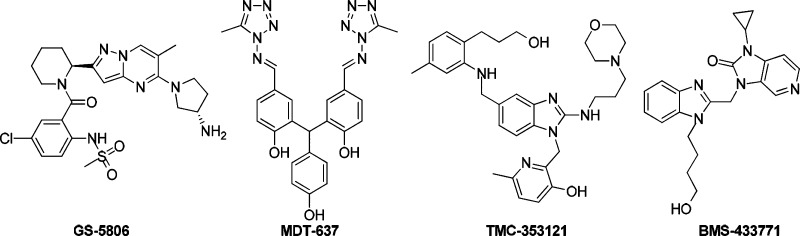

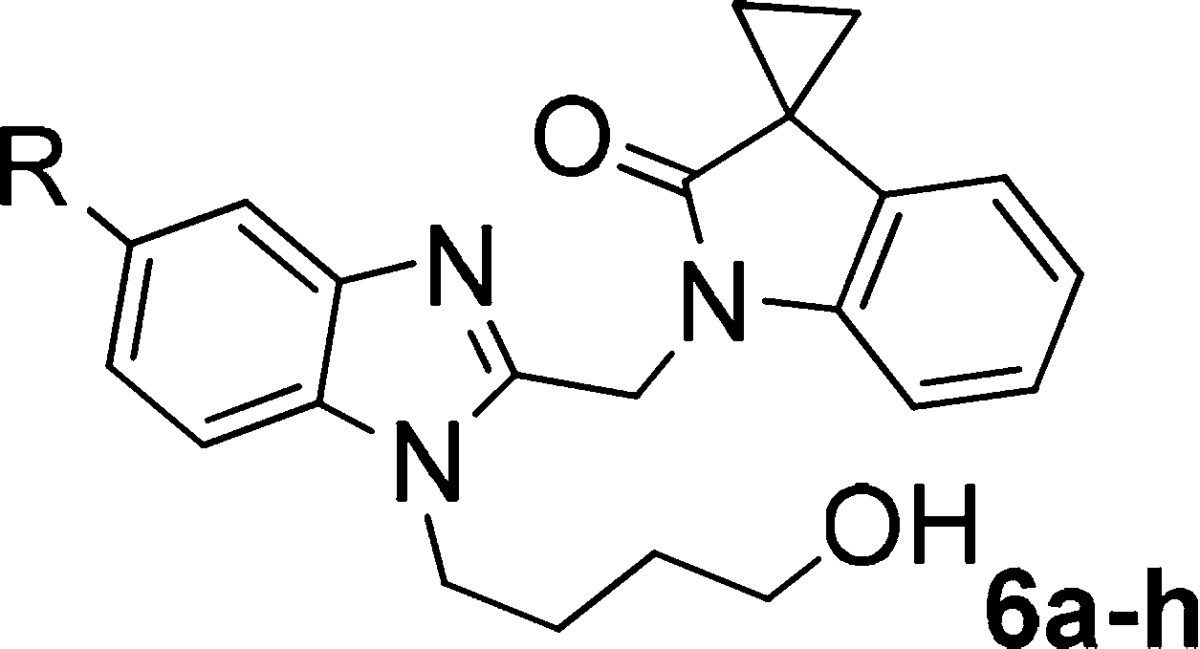

Clearly, there is an unmet need for a new drug to prevent and treat RSV infection. In the past two decades, several chemical series of RSV fusion protein inhibitors have been reported (Figure 1), including the most advanced compound GS-5806, which is currently in Phase 2 study.4,5 Another Phase 2 compound is MDT-637 (formerly VP-14637) and is being developed as a dry powder inhaled product due to its low oral bioavailability. Both BMS-4337716 and TMC-3531217 were progressed into late preclinical/early clinical development but discontinued, mainly due to the unfavorable pharmaceutical properties or early safety findings. The two RSV F protein inhibitors contain the same benzimidazole heterocycle. Therefore, we intend to address the drug-like properties of benzimidazole RSV fusion inhibitors especially improving activity in vitro, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Herein, we describe the identification of a promising candidate isopropyl 1′-((5-bromo-1-(4-hydroxybutyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methyl)-2′-oxospiro[azetidine-3,3′-indoline]-1-carboxylate (14h) that was effective in a mouse challenge model of RSV infection. Meanwhile, the extensive structure–activity relationship (SAR) of this 3,3′-spirocyclic-2-oxo-indoline derivative was revealed herein.

Figure 1.

RSV inhibitors explored in early stage clinical studies.

Results and Discussion

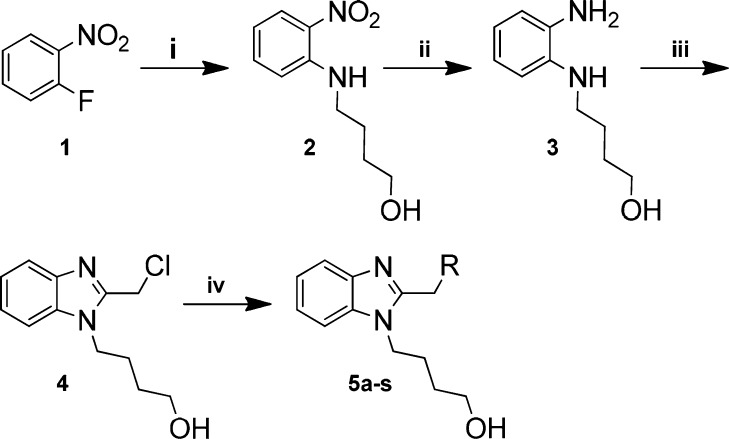

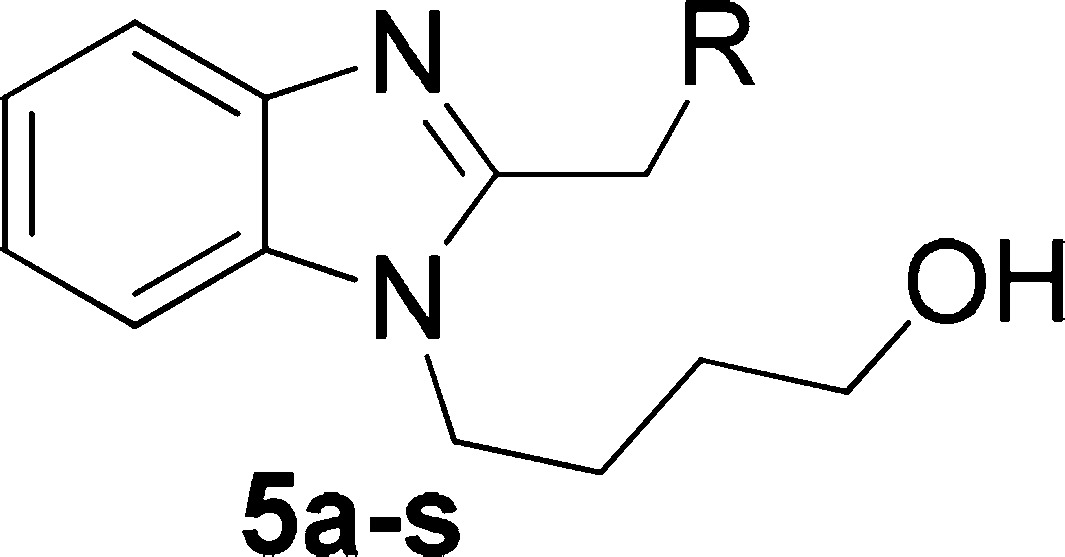

In order to investigate a strategy of pyridinoimidazolone replacements on BMS-433771, a small library containing 19 scaffold hopping derivatives were designed and synthesized (Scheme 1). The key intermediate 4 was prepared from starting material 1 via displacement reaction and hydrogenation reaction followed by cyclization reaction with excellent overall yields (68.4%). The target compounds 5a–s were obtained by alkylation reaction of intermediate 4 in the presence of K2CO3 in CH3CN or NaH in DMF.

Scheme 1. General Synthesis of Pyridinoimidazolone Replacements Analogs.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 4-aminobutan-1-ol, Et3N, dioxane, 90%; (ii) Pd/C, H2, MeOH, 95%; (iii) 2-chloroacetic acid, 4 N HCI, 80 °C, −60%; (iv) for 5a–g, 5j–p, K2CO3, MeCN, 70 °C, or NaH, DMF, 20 °C; for 5h/i, K2CO3, then Pd(OH)2; for 5q–s, K2CO3, then TFA.

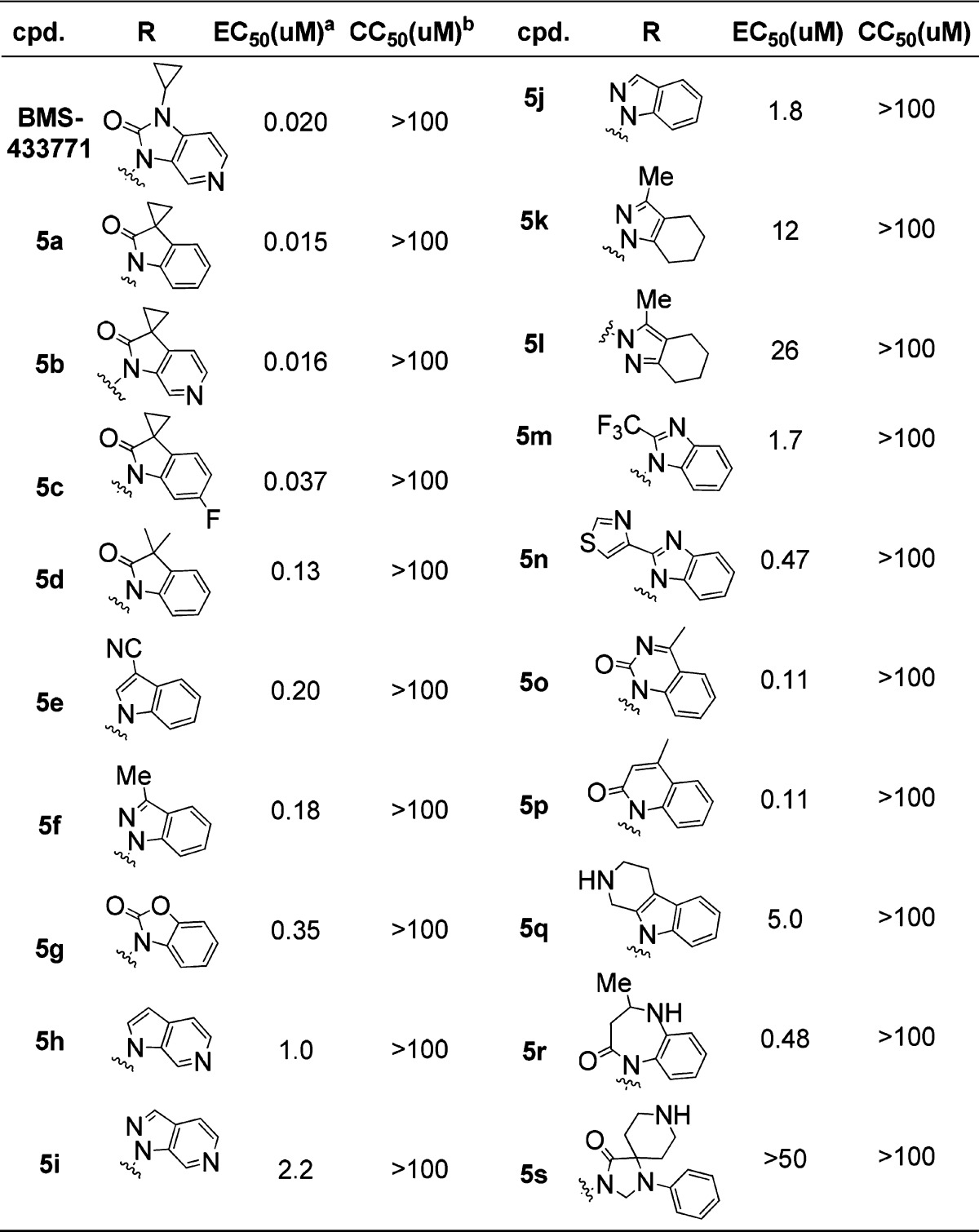

Cyclopropyl indolin-2-one 5a was first recorded in ReViral Ltd.’s patent for RSV treatment, but no antiviral activity was reported.8 Hoffmann-La Roche disclosed spiro azaindolin-2-one analogs; however, only spirocylicpropanes were introduced.9−11 In order to perform pyridinoimidazolone replacement strategy, 5a–c were synthesized and evaluated by the CPE assay. The antiviral activities were listed in Table 1. The importance of the carbonyl group for the activities against RSV was demonstrated when its replacement with a hydrogen (5e and 5f, with EC50 of 0.20 and 0.18 μM, respectively) resulted in a moderate activity in comparison to BMS-433771. The presence of a small aliphatic substituent at the ortho-position of carbonyl was also found to be desirable (5g–j). Attempt to replace the fused phenyl ring with saturated ring resulted in a 100-fold less active compound 5k with an EC50 of 12 μM versus 5f. Other pyridinoimidazolone replacements (5m–s) showed negative impact on activities. In summary, though the SAR for pyridinoimidazolone replacement strategy is kind of rigid, the ring system 3,3′-spiro[cyclopropane]-2-oxo-indoline (5a–c) was identified to gain a superior level of activity.

Table 1. Antiviral Activity of a Small Library of Pyridinoimidazolone Replacements.

RSV CPE assay in Hep-2 cells; data was generated from two or more determinations.

CC50 was performed on the same cells and with the same method.

As a new chemical starting point, chloride (6a) and methyl group (6b) were introduced at the 5-position of the corresponding benzimidazole moiety following Feng’s work on imidazolepyrimidines.12,13 Unfortunately, both of these two compounds did not boost the antiviral activities, demonstrating 10 and 16 nM, respectively, versus 15 nM of 5a (Table 2). In the meantime, an entire attrition was observed on 5-cyclohexyl substituent (6c) possibly due to increased steric bulk, electronic withdrawing groups 5-CN (6e) and 5-CF3 (6f) attenuated the activities by more than 10-fold. Single-digital nanomolar activity was obtained when bromine was introduced, and 6h demonstrated 7-fold potency improvement in comparison to 5a. Given that the introduction of 5-bromo had a significant impact on anti-RSV activity, we decided to pursue 5-bromobenzimidazole moiety for further SAR optimizations.

Table 2. Antiviral Activity of Compounds 6a–i.

| cpd. | R | EC50(nM)a | CC50(μM)b | cpd. | R | EC50(nM) | CC50(μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 5-H | 15 | >100 | 6e | 5-CN | 190 | >100 |

| 6a | 5-Cl | 10 | >100 | 6f | 5-CF3 | 210 | >100 |

| 6b | 5-Me | 16 | >100 | 6g | 5-CH2NH2 | 7.0 | >100 |

| 6c | 5-cyclohexyl | >10000 | >100 | 6h | 5-Br | 2.3 | >100 |

| 6d | 5-F | 13 | >100 | 6i | 5-l | 21 | >100 |

RSV CPE assay in Hep-2 cells; data was generated from two or more determinations.

CC50 was performed on the same cells and with the same method.

Furthermore, 3,3′-spirocylic-2-oxo-indolines are found in compounds that exert a range of pharmacological activities. Analog 3,3′-spiro[succinimide]-2-oxo-indoline antagonized chemoattractant receptor-homologs expressed on Th2 lymphocytes (CRTH2 or DP2),14 and 3,3′-spiro[piperidine]-2-oxo-indolines were in development for cathepsin K inhibitors.15 Therefore, the following study focused on optimizing the 3,3′-spirocylic-2-oxo-indoline moiety of 6h.

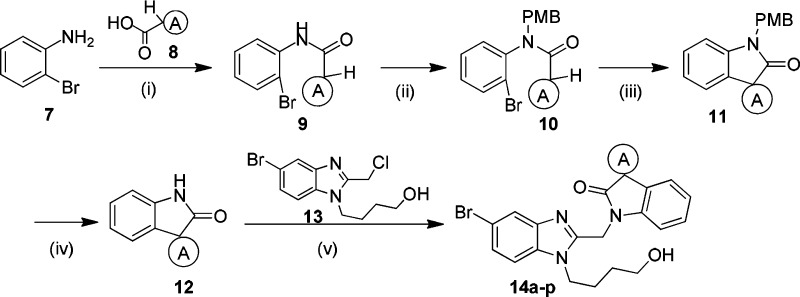

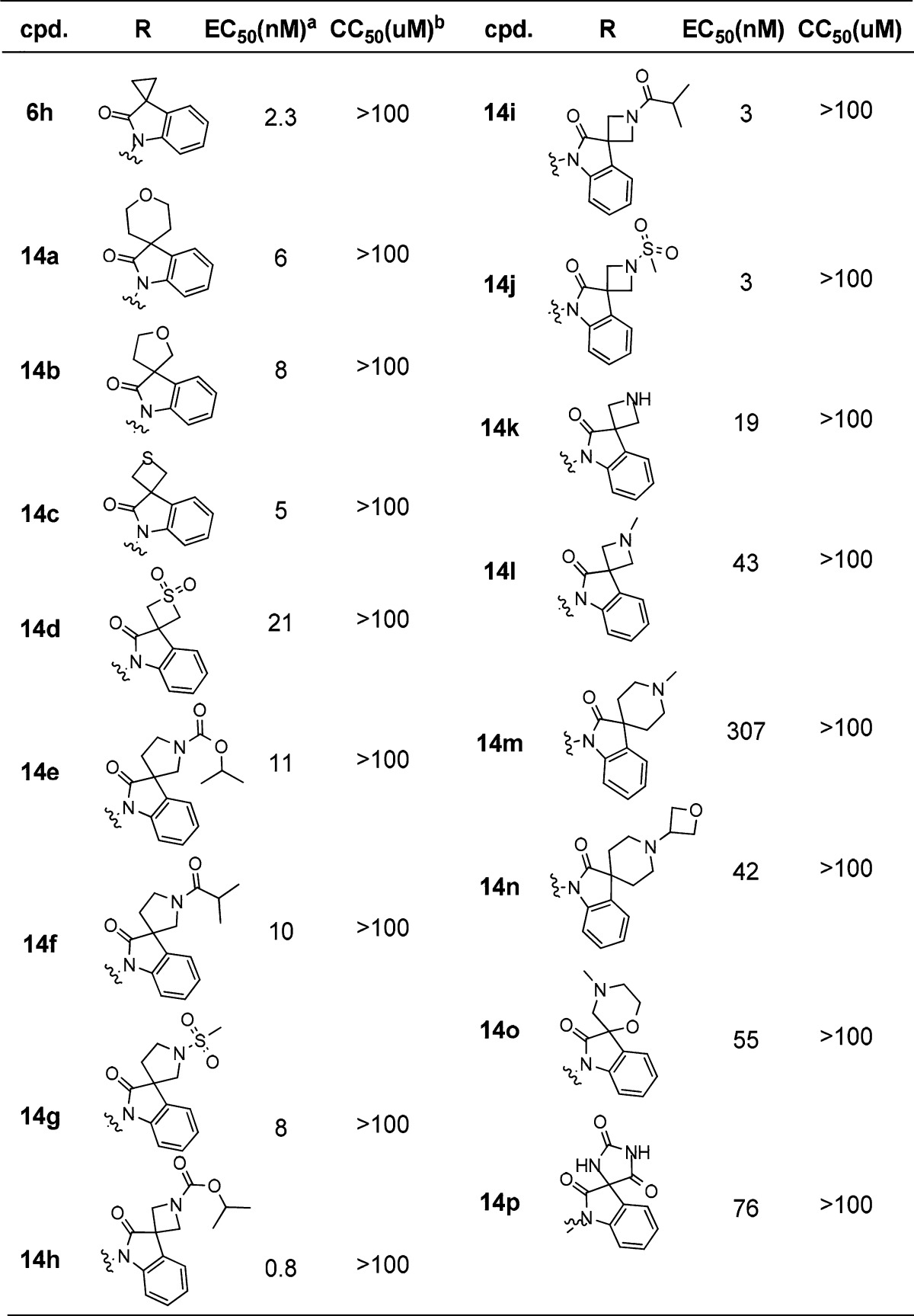

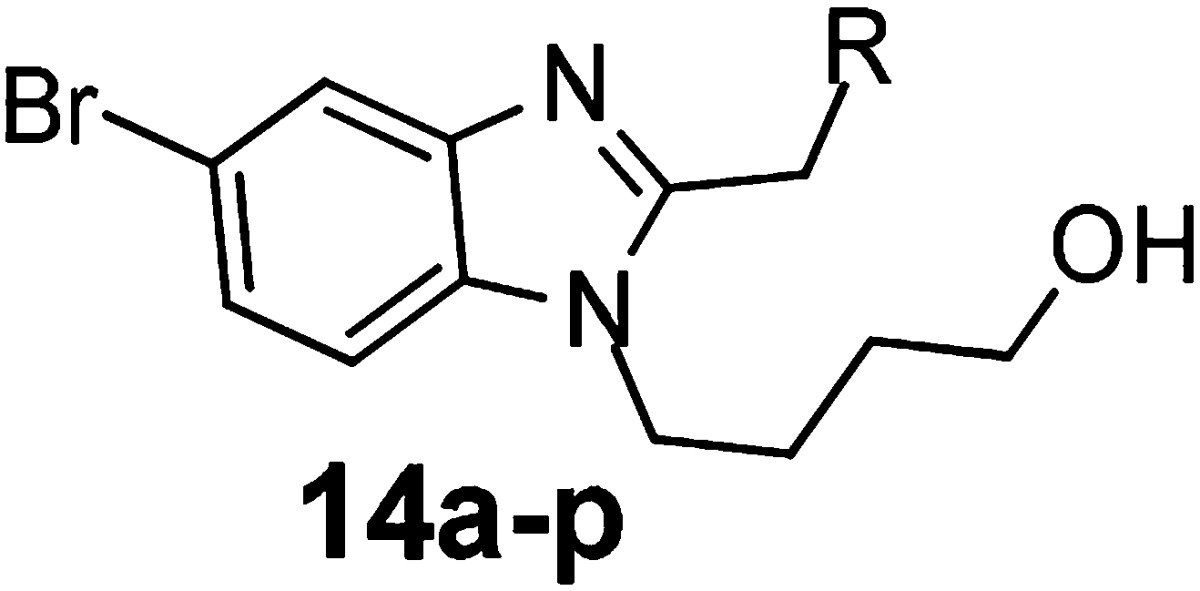

In order to explore more potent 3,3-spirocylic-2-oxo-indoline derivatives, a small library of spiroheterocyclic analogs was successfully designed and synthesized. The synthesis of intermediate 12, as shown in Scheme 2, was generally commenced with commercially available 2-bromo aniline, which was condensed with the acid 8 via T3P to generate the amide 9, followed by alkylation with PBMCl to yield intermediates 10. This intermediate was then subjected to an intramolecular palladium-catalyzed α-arylation reaction.16 After removal of PMB via in CAN or TfOH acid conditions, intermediate 12 was generated in moderate to good yield (30–75%). As shown in Table 3, 14a and 14b displayed good potency, with EC50 of 6 and 8 nM. Sulfide 14c and sulfone 14d exhibited 5 and 21 nM antiviral activities, respectively. Encouraged by the tolerances of heteroatoms, nitrogen was introduced. Five-membered analogs 14e, 14f, and 14g attenuated 4–5-fold anti-RSV activities compared with 6h. However, four-membered azetidine spiro analogs, isopropyl carbamate 14h, improved the antiviral activity into subnanomolar level of 0.8 nM, 3-fold more potent compared to that of 6h, and isobutyl amide 14i and methanesulfonyl amide 14j exhibited comparable activities of 3 nM. Other approaches of aliphatic amine (14k–l) and steric bulky six-membered spiro rings (14m–p) attenuated the activities.

Scheme 2. Synthetic Route To Produce Key Intermediate 12.

Reagents and conditions: (i) T3P, ethyl acetate, 30 °C, 90%; (ii) PMBCI, DMF, NaH 30 °C, or Cs2CO3, 90 °C, 85%; (iii) i-Pr-PEPPSI, tBuONa, 1,4-dioxane, 90 °C, 65%; (iv) CAN, acetonitrile, 0 °C, 30% or CF3SO3H, TFA, 30 °C, 75%; (v) K2CO3, MeCN, 70 °C, or NaH, DMF, 20 °C, 70–90%.

Table 3. Antiviral Activity of 3,3-Spirocyclic-2-oxo-indoline Derivatives 14a–p.

RSV CPE assay in Hep-2 cells; data was generated from two or more determinations.

CC50 was performed on the same cells and with the same method.

PK Results and Discussion

Plasma pharmacokinetics after 1 mg/kg intravenous and 10 mg/kg oral administration of compound 14h and BMS4337716 to female balb/c mice were characterized. PK parameters were listed in Table 4, indicating that compound 14h showed lower clearance and volume of distribution (Vd), but higher AUC with similar half-life (T1/2). However, compound 14h had much better oral profile than that of BMS433771, as evidenced by oral exposure (8076 versus 1170 nM·h) and absolute oral bioavailability (71% versus 13%).

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters after Single Intravenous and Oral Administration of 14h and BMS433771 to Female Balb/c Micea.

| cpd. | 14h | BMS-433771 |

|---|---|---|

| i.v. @ 1 mpk | ||

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 28 | 67 |

| T1/2 (h) | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Vd (L/kg) | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| AUC0-inf (nM·h) | 1130 | 920 |

| p.o. @ 10 mpk | ||

| Cmax (nM) | 3319 | 2098 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| AUC0-inf (nM·h) | 8076 | 1170 |

| %F | 71 | 13 |

Data reported are mean values from the dosing cohorts (Female Balb/c-Mouse, fasted, n = 3/dose). Dosages are 1 mg/kg i.v. (1 mg/mL in DMSO/PEG400/water = 5:40:55, clear solution) and 10 mg/kg p.o. (2 mg/mL in DMSO/PEG400/water = 5:40:55, clear solution). CL stands for plasma clearance. T1/2 is the plasma half-life of the compounds. Vd means volume of distribution. Cmax represents the highest observed plasma concentration, and Tmax is time to reach Cmax. AUC is the area under the plasma concentration–time curve. %F represents absolute oral bioavailability.

Pharmacology Results and Discussion

The in vivo efficacy was evaluated in the Balb/c mouse RSV infection model. As shown in Table 5, compound 14h showed a clear dose-dependent effect on virus load reduction from 5 to 50 mg/kg. In addition, the 5 mg/kg group of 14h reduced the lung tissue virus load Δlog10 to 1.6, which was superior to BMS-433771, 1.2 Δlog10 at 50 mg/kg dose. Moreover, the 50 mg/kg group of 14h reduced the virus load of all the experimental animals to below the detection limit, which demonstrated that compound 14h exhibited excellent anti-RSV efficacy and was significantly superior to BMS433771 in this RSV mouse challenge model.

Table 5. In Vivo Antiviral Activity in a Mouse Model of RSV Infection.

| group (n = 7) | viral load in lung (Log10 pfu/g lung) | viral load reduction in lung (Δlog10) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 3.91 ± 0.10 | |

| BMS433771-50 mpk | 2.75 ± 0.20 | 1.16 ± 0.24 |

| 14h-5 mpk | 2.27 ± 0.24 | 1.64 ± 0.26 |

| 14h-15 mpk | 1.86 ± 0.31 | 2.05 ± 0.31 |

| 14h-50 mpk | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 3.91 |

Conclusion

In summary, we have explored a series of 3,3′-spiro[azetidine]-2-oxo-indoline derivatives proved to be potent inhibitors of RSV in the CPE assay. The investigation led to the identification of 14h as a compound demonstrating additional efficacy in the Balb/c mouse model of RSV infection after oral dosing. Further safety assessment will be conducted in due course.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- PO

per oral

- Cmax

peak concentration

- Tmax

time to peak

- CL

clearance

- T1/2

half-life

- Vd

volume of distribution

- AUC

area under curve

- mpk

mg/kg

- %F

oral bioavailability

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00418.

Synthetic procedures, analytical data, and assay protocol (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Storey S. Respiratory syncytial virus market. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9 (1), 15–16. 10.1038/nrd3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. B.; Weinberg G. A.; Iwane M. K.; Blumkin A. K.; Edwards K. M.; Staat M. A.; Auinger P.; Griffin M. R.; Poehling K. A.; Erdman D.; Grijalva C. G.; Zhu Y.; Szilagyi P. The Burden of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in Young Children. New. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360 (6), 588–598. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair H.; Nokes D. J.; Gessner B. D.; Dherani M.; Madhi S. A.; Singleton R. J.; O’Brien K. L.; Roca A.; Wright P. F.; Bruce N.; Chandran A.; Theodoratou E.; Sutanto A.; Sedyaningsih E. R.; Ngama M.; Munywoki P. K.; Kartasasmita C.; Simôes E. A.; Rudan I.; Weber M. W.; Campbell H. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375 (9725), 1545–1555. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackman R. L.; Sangi M.; Sperandio D.; Parrish J. P.; Eisenberg E.; Perron M.; Hui H.; Zhang L.; Siegel D.; Yang H.; Saunders O.; Boojamra C.; Lee G.; Samuel D.; Babaoglu K.; Carey A.; Gilbert B. E.; Piedra P. A.; Strickley R.; Iwata Q.; Hayes J.; Stray K.; Kinkade A.; Theodore D.; Jordan R.; Desai M.; Cihlar T. Discovery of an oral respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion inhibitor (GS-5806) and clinical proof of concept in a human RSV challenge study. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (4), 1630–1643. 10.1021/jm5017768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVincenzo J. P.; Whitley R. J.; Machman R. L.; Weinlich C. S.; Harrison L.; Farrell E.; McBride S.; Williams R. L.; Jordan R.; Xin Y.; Ramanathan S.; O’Riordan T.; Lewis S. A.; Li X.; Toback S. L.; Lin S. L.; Chien J. W. Oral GS-5806 activity in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. New. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371 (8), 711–722. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K. L.; Sin N.; Civiello R. L.; Wang X. A.; Combrink K. D.; Gulgeze H. B.; Venables B. L.; Wright J. J.; Dalterio R. A.; Zadjura L.; Marino A.; Dando S.; D’Arienzo C.; Kadow K. F.; Cianci C. W.; Li Z.; Clarke J.; Genovesi E. V.; Medina I.; Lamb L.; Colonno R. J.; Yang Z.; Krystal M.; Meanwell N. A. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion inhibitors. Part 4: optimization for oral bioavailability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17 (4), 895–901. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti J. F.; Meyer C.; Doublet F.; Fortin J.; Muller P.; Queguiner L.; Gevers T.; Janssens P.; Szel H.; Willebrords R.; Timmerman P.; Wuyts K.; van Remoortere P.; Janssens F.; Wigerinck P.; Andries K. Selection of a respiratory syncytial virus fusion inhibitor clinical candidate. 2. Discovery of a morpholinopropylaminobenzimidazole derivative (TMC353121). J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51 (4), 875–896. 10.1021/jm701284j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerill S.; Pilkington C.; Lumley J.; Angell R.; Mathews N.. Pharmaceutical compounds. WO2013/68769.

- Feng S.; Gao L.; Guo L.; Huang M.; Liang C.; Wang B.; Wang L.; Wu G.; Yun H.; Zhang W.; Zheng X.; Zhu W.. Aza-oxo-indoles for the treatment and prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus infection. WO2014/184163.

- Gao L.; Guo L.; Liang C.; Wang B.; Wang L.; Yun H.; Zhang W.; Zheng X.. Novel aza-oxo-indoles for the treatment and prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus infection. WO2015/22263.

- Wang L.; Yun H.; Zhang W.; Zheng X.. Novel aza-oxo-indoles for the treatment and prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus infection. WO2015/22301.

- Feng S.; Hong D.; Wang B.; Zheng X.; Miao K.; Wang L.; Yun H.; Gao L.; Zhao S.; Shen H. C. Discovery of imidazopyridine derivatives as highly potent respiratory syncytial virus fusion inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6 (3), 359–362. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S.; Li C.; Chen D.; Zheng X.; Yun H.; Gao L.; Shen H. C. Discovery of methylsulfonyl indazoles as potent and orally active respiratory syncytial Virus(RSV) fusion inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 1147–1157. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani S.; Page P.; Missotten M.; Colovray V.; Cleva C.; Arrighi J. F.; Atherall J.; Macritchie J.; Martin T.; Humbert Y.; Gaudet M.; Pupowicz D.; Maio M.; Pittet P. A.; Golzio L.; Giachetti C.; Rocha C.; Bernardinelli G.; Filinchuk Y.; Scheer A.; Schwarz M. K.; Chollet A. Discovery of a New Class of Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable CRTH2 (DP2) Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Allergic Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51 (7), 2227–2243. 10.1021/jm701383e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno N.; Masuya K.; Ehara T.; Kosaka T.; Miyake T.; Irie O.; Hitomi Y.; Matsuura N.; Umemura I.; Iwasaki G.; Fukaya H.; Toriyama K.; Uchiyama N.; Nonomura K.; Sugiyama I.; Kometani M. Effect of Cathepsin K Inhibitors on Bone Resorption. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51 (17), 5459–5462. 10.1021/jm800626a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferkorn J. A.; Choi C. Convenient synthesis of 1,1′-H-spiro[indoline-3,30-piperidine]. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49 (28), 4372–4373. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.05.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.