Abstract

Diseases of the liver and biliary tree have been described with significant frequency among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and its advanced state, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Through a variety of mechanisms, HIV/AIDS has been shown to affect the hepatic parenchyma and biliary tree, leading to liver inflammation and biliary strictures. One of the potential hepatobiliary complications of this viral infection is AIDS cholangiopathy, a syndrome of biliary obstruction and liver damage due to infection-related strictures of the biliary tract. AIDS cholangiopathy is highly associated with opportunistic infections and advanced immunosuppression in AIDS patients, and due to the increased availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy, is now primarily seen in instances of poor access to anti-retroviral therapy and medication non-compliance. While current published literature describes well the clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic management of AIDS-related cholangiopathy, information on its epidemiology, natural history, and pathology are not as well defined. The objective of this review is to summarize the available literature on AIDS cholangiopathy, emphasizing its epidemiology, course of disease, and determinants, while also revealing an updated approach for its evaluation and management.

Keywords: Prognosis, Human immunodeficiency virus complications, Epidemiology, Human immunodeficiency virus cholangiopathy, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Mortality

Core tip: Though a declining phenomenon in the Western world, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related cholangiopathy has been shown to cause significant burden and remains an important etiology of hepatobiliary pathology in those affected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). While it is linked to advanced immunosuppression in AIDS patients, particularly in those with extremely low CD4 counts and opportunistic infections, as well as those with drug-resistant HIV infection, it is also seen in developing countries due to less available anti-retroviral therapy, decreased awareness, and medication non-compliance.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a global pandemic and it has been estimated that 37 million people are infected with it worldwide. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is associated with high morbidity and mortality due to increased risk of opportunistic infections and malignancy[1]. However, there has been significant decline in morbidity and mortality associated with HIV/AIDS with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)[2]. In December of 2013, UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS) proposed new targets for HIV treatment scale-up i.e., by 2020, 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy and 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression for effective control of HIV[3].

HIV affects the hepatic parenchyma and biliary tree, leading to liver inflammation and biliary strictures. According to observational cohort studies published by the D.A.D. study group (Data collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV drugs) and Palella et al[4], deaths in HIV infection due to liver disease are on the rise; approximately 14%-18% of deaths among HIV/AIDS patients were attributed to liver diseases in these studies[5].

Hepatobiliary dysfunction is common in HIV/AIDS. It has been well established that HIV directly affects hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and endothelial cells[6]. Abnormalities in liver chemistries are common among HIV-infected persons, even in the absence of hepatitis B and C infections. Mechanisms by which HIV exerts its effect on hepatocytes include but are not limited to: oxidative stress secondary to mitochondrial injury, lipotoxicity, immune-mediated cell damage, accumulation of toxic metabolites within hepatocytes, and translocation of gut microbiota causing systemic inflammation, senescence, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia[7].

Liver diseases in HIV are generally classified into three main categories. The first group consists of diseases associated with immunosuppression, including AIDS cholangiopathy, acalculous cholecystitis, AIDS-related neoplasms (non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma), and vanishing bile duct syndrome. The next set relates to drug-induced hepatotoxicity secondary to HAART. The last category involves worsening of co-infection with hepatitis B and C viruses, encompassing accelerated liver damage and progression of fibrosis. In addition, patient with HIV/AIDS are at increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and nodular regenerative hyperplasia[8].

AIDS cholangiopathy is a well-documented biliary syndrome in severely immunocompromised AIDS patients[9]. It occurs when strictures in the biliary tract develop due to opportunistic infections, leading to biliary obstruction and cholestatic liver damage[10]. The condition was first recognized in 1983 by Pitlik et al[11] and Guarda et al[12] among immunocompromised humans. Following these reports, investigations of right upper quadrant pain and elevated liver enzymes in severely immunocompromised AIDS patients revealed several opportunistic pathogens, implicating the pathogenesis of AIDS cholangiopathy[13]. Furthermore, Schneiderman et al[14] published a case series in 1987 highlighting the endoscopic appearance of papillary stenosis involving the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree and associated with sclerosing cholangitis. In 1989, Cello identified four patterns of cholangiographic features resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), including papillary stenosis, long extrahepatic strictures, acalculous cholecystitis, and intrahepatic and extrahepatic sclerosing lesions[15].

Several case series and reviews are published highlighting the clinical, biochemical, and endoscopic management of AIDS-related cholangiopathy. Still, little is known about its epidemiology and natural history, as well as the determinants of its pathology in developed and developing countries. In this review article, we will focus on the epidemiology, determinants, and management of AIDS related cholangiopathy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Actual data on the incidence and prevalence of AIDS-related cholangiopathy is largely lacking, especially from developing countries. In the pre-HAART era, the estimated prevalence of this entity was 26%-46%[16]. To date, approximately 250 cases are reported in the literature-mostly before the introduction of HAART. Although rarely reported in developed countries, AIDS-related cholangiopathy remains an important differential of cholestatic liver disease in HIV-infected patients, attributable to resistance to the first line antiretroviral medications[17]. Meanwhile, it is still a problem in developing countries due to poor access to HAART, decreased awareness about the disease, and medication non-compliance[18].

DETERMINANTS

Although exact knowledge about the natural history of AIDS cholangiopathy and its determinants is not available from currently published literature, the disease is found to be associated with advanced immunosuppression (CD4 count < 100/mm3). Approximately 82% of patients with this disease have opportunistic infections at the time of diagnosis[19]. At the time of diagnosis of cholangitis in AIDS patients, approximately 27% have been found to also have Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, 100% with candidiasis, 20% with HSV infection, and 26% with cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma[20]. AIDS-related cholangitis is most commonly reported in young men who have sex with men with a mean age of 37 years[21]. Conversely, it is more common in heterosexual men in developing counties and rarely associated with Kaposi sarcoma[22].

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Opportunistic infections of the biliary tract associated with advanced immunosuppression in AIDS has been well documented in the literature. Cryptosporidium parvum (C. parvum) is the most common pathogen associated with AIDS cholangiopathy and has been has been isolated in 20%-57% of patients[23]. Sources of samples for diagnosis include: bile duct epithelium by ampullary biopsy, bile samples, and stool samples. Epidemiological studies show that C. parvum-associated diarrhea is common in developed and developing countries and can be seen in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts[24]. However, cholangiopathy is only reported in the immunocompromised state associated with AIDS. The incidence of C. parvum infection in AIDS patients is reported to be 3%-4% in developed countries and approximately 50% in patients in the developing world prior to the advent of HAART[25]. This pathogen is still the most common infectious cause of AIDS cholangiopathy in patients who either do not have access to medications or have documented resistance to first-line HAART.

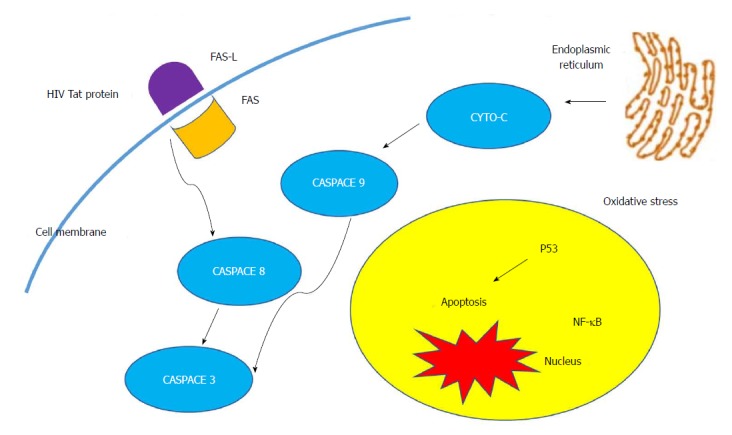

It has been proposed that HIV and C. parvum acts synergistically in the biliary system. The mechanism by which C. parvum causes AIDS cholangiopathy is not entirely clear. Results of the in vitro study published by O’Hara and associates in 2007 suggests that C. parvum induces apoptotic cell death in the infected cholangiocytes through Fas/Fas ligand (FasL) system which is further potentiated by the synergistic effects of the HIV-1 trans-activator of transcription (Tat) protein (Figure 1). FasL protein expression in the cytoplasm of the cultured hepatocyte and its translocation is enhanced by the HIV-1 Tat protein. In addition, the HIV-1 Tat protein causes release of full-length FasL in infected cells; consequently, apoptotic cell death in uninfected cholangiocytes leads to damage of the biliary epithelia, which occurs almost exclusively in patients infected with HIV[26,27]. Another proposed mechanism of pathology is autonomic nerve damage in the intestine caused by C. parvum, resulting in sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and papillary stenosis, which is in turn linked to disordered motility in the biliary tract[28].

Figure 1.

Molecular mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus cholangiopathy induced by Cryptosporidium parvum.

The next-most common pathogen implicated in the pathogenesis of AIDS cholangiopathy is cytomegalovirus (CMV). It is estimated that 10%-20% of AIDS cholangitis is caused by CMV. Here, the damage is usually found in the arterioles close to the biliary canals, rather than within biliary epithelial cells. It has been postulated that CMV causes vascular injury leading to ischemic damage[15].

Microsporidia is another opportunistic pathogen that has been found to be associated with AIDS cholangiopathy in immunocompromised hosts. The estimated prevalence of AIDS cholangiopathy caused by microsporidia is around 10%, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi (E. bieneusi) is involved in 80%-90% of these cases. A series of 20 cases reported by some researchers showed that E. bieneusi was the only causative organism in those HIV-infected patients with diarrhea. Another study published by Pol et al[29] found this pathogen in the biliary samples of all 8 patient studies[30].

There are several other pathogens implicated in AIDS cholangiopathy, but are less well-described. Isospora is a well-known opportunistic pathogen in AIDS patients associated with chronic diarrhea; however, its association with AIDS cholangiopathy is relatively underestimated[31]. Recently, Histoplasma capsulatum was also reported in HIV infections, causing structural changes suggestive of AIDS cholangiopathy. In some cases, multiple pathogens are involved in the pathogenesis[32]. Clearly, there are several opportunistic infections associated with the development of cholangiopathy in AIDS, with the most common being C. parvum, CMV, and E. bieneusi.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical, biochemical and imaging studies necessary for the diagnosis of AIDS related cholangiopathy are as follows:

Symptoms and signs

The clinical presentation of AIDS cholangiopathy is variable, ranging from asymptomatic disease to severe right upper quadrant pain associated with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Presence of papillary stenosis is the primary determinant of abdominal pain severity. Less common presenting features include fever and jaundice, usually seen with complete bile duct obstruction. When present, fevers are usually low-grade, but spiking high-grade fevers can be seen with superimposed bacterial cholangitis. Substantial weight loss is also seen commonly, while pruritus is uncommon. On physical examination, abdominal tenderness and hepatomegaly are reported in some case reports[21,33,34].

Laboratory criteria

Elevated liver enzymes, especially markedly elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), is the most common biochemical abnormality associated with AIDS cholangiopathy. It is especially seen in AIDS cholangiopathy associated with disseminated mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). Obstruction of the smaller branches of the biliary tree due to granulomatous infiltration from disseminated MAC is the possible underlying explanation. Only mild to moderate elevation has been observed in other liver chemistries such as alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase. Serum bilirubin may remain normal or elevated, depending on the severity of papillary duct stenosis. In approximately one-fourth of patients, the presentation of AIDS cholangiopathy is subtle and not associated with any biochemical abnormalities despite the evidence of cholangiographic abnormalities on imaging studies[35,36].

Liver biopsy

Microscopically, the changes of AIDS cholangiopathy are usually consistent with sclerosing cholangitis[37].

Imaging studies

Ultrasound: Being cost-effective, sonography is an ideal screening imaging modality in an HIV-infected patient suspected to have hepatobiliary pathology. The most common abnormalities associated with AIDS cholangiopathy include the dilatation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts, followed by a prominent/dilated common bile duct (CBD), and in some patients, a beaded appearance can also be noted. According to a study published by Daly and associates, ultrasound is 98% accurate in predicting normal or abnormal endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in AIDS cholangiopathy-it is 97% sensitive and 100% specific in predicting ERCP abnormalities in this clinical setting. Another commonly seen abnormality is the presence of hyperechoic echogenic nodules at the distal end of the CBD, which represents edema of the papilla of Vater noted on ERCP[38,39].

Contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography: Computed tomography (CT) scans are used widely to evaluate causes of acute and chronic abdominal pain, such as acute pancreatitis in HIV-infected patients. Abdominal CT scans with contrast provide detailed information about hepatic and pancreatic parenchyma and vasculature. In HIV cholangitis, findings of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation in the absence of external compression from malignant masses are seen commonly[40].

Cholangiography: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is noninvasive and has similar sensitivity to ERCP in diagnosing the characteristic findings of AIDS cholangiopathy. In addition, the risk of complications seen more in ERCP such as iatrogenic pancreatitis, duodenal perforation, hemorrhage, and ascending cholangitis are rare. Currently, MRCP is preferred over ERCP unless there is need for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, such as brushing, sphincterotomy, or placement of stents due to biliary strictures.

According to the published literature, the most common cholangiographic finding in AIDS cholangiopathy is papillary stenosis, which is a smoothly tapered stricture at the distal end of the CBD at the level of the hepatopancreatic ampulla. In two-thirds of cases, papillary stenosis is present either alone or in combination with intrahepatic ductal dilatation and multifocal intrahepatic biliary strictures with alternating normal segments, or saccular dilatations. The characteristic “beaded” appearance of intrahepatic sclerosing cholangitis-like pattern without intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct abnormalities is observed in 20% of patients. The fourth cholangiographic pattern seen in 6%-15% of patients corresponds to a 1-3 cm segmental extrahepatic biliary stricture with or without intrahepatic involvement[41-43].

Management

Symptomatic treatment with opioids such as morphine and CT-guided celiac plexus block has been effective in alleviating abdominal pain[44]. Treatment of opportunistic infections is surprisingly ineffective in halting the progression of sclerosing cholangitis and papillary stenosis. Cryptosporidium, by far the most common pathogen implicated in the pathogenesis of AIDS cholangitis, has no effective eradication therapy[45]. In a few studies, paromomycin, azithromycin, and more recently nitazoxanide have been used without promising results[46,47]. Intravenous gancyclovir and foscarnet are also not beneficial for treatment of CMV-related cholangitis[48]. Though albendazole has been used with some success in disseminated Enterocytozoon intestinalis infection including cholangitis, the therapeutic effect seems to be transient[49]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for cyclopora has been used with little success[50]. Treatment is recommended with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in addition to ivermectin for isospora[51].

Use of ursodeoxycholic acid (URSO) in AIDS cholangiopathy is associated with symptomatic improvement in abdominal pain and normalization of liver chemistries after sphincterotomy for papillary stenosis[52]. According to the pilot study published by Castiella et al[53] in 1997, which included four patients with AIDS cholangiopathy treated with URSO, 100% reported resolution in abdominal pain after 2-4 mo on treatment, and 50% showed improvement in alkaline phosphatase. The mechanism for improvement in pain and liver chemistries with URSO treatment in AIDS cholangiopathy is not yet clear.

To date, the best treatment of opportunistic pathogens causing AIDS-related cholangiopathy is restoration of immune function using HAART or switching to second-line HAART if there is evidence of resistance. The data regarding improvement in clinical symptoms and radiological findings after HAART initiation is conflicting. While most case series studies show improvement in abdominal pain, normalization of liver chemistries, and decrease in the progression of intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary involvement, a case described by Imai et al[54] showed that intrahepatic biliary duct stenosis progressed even after the timely initiation of HAART[55].

Endoscopic sphincterotomy usually provides symptomatic relief of abdominal pain in cholangitis associated with papillary stenosis by decompressing the bile ducts and improving drainage in the biliary tree. The value of endoscopic sphincterotomy has been evaluated in multiple case series. Endpoints of follow-up evaluation were improvement in pain score and cholestasis, decrease in the biliary dilatation, and decreased progression of sclerosing cholangitis. According to the prospective study published by Cello et al[56], ERCP sphincterotomy was associated with significant improvement in pain scores up to at least 9 mo of follow-up. However, there was no significant improvement in the level of alkaline phosphatase, and progression of intrahepatic sclerosing cholangitis was observed. These findings are supported by several other studies as well. Though experience is limited, there have been reports of successful biliary stent use in patients with both long and proximal strictures[57].

PROGNOSIS

The survival of patient with AIDS cholangiopathy is generally poor because of disease association with advanced stages of immunosuppression and the presence of multiple opportunistic infections. In the pre-HAART era, 1-year survival was reported to be 14%-41% with a mean survival of 7-12 mo[58,59]. Remarkable improvement was reported in the median survival of the patients with AIDS cholangiopathy during the last decade, including reports of up to 34 mo median survival. This is thought to be due to earlier diagnosis and management of HIV/AIDS, and improved access to HAART. According to the prospective study published by Ko[60], the factors associated with poor prognosis in AIDS cholangiopathy include history or presence of opportunistic infections, and elevation in the level of alkaline phosphatase eight times above the upper limit of normal. CD4 count, severity of cholangiopathy, and sphincterotomy for decompression of the biliary tract each have no effect on mortality. In the same study, factors associated with improved survival of the patient but became insignificant after adjusting for confounding factors were older age (30 years or older), the absence of opportunistic infection, diagnosis of AIDS after 1993, and AIDS cholangiopathy after 1996.

COMPLICATIONS

So far, the primary complications reported to be caused by AIDS-related cholangiopathy are development of cholangiocarcinoma and progression of sclerosing cholangitis despite appropriate treatment. Chronic biliary infection from opportunistic pathogens seen in AIDS cholangiopathy initiate the dysplastic process in the biliary epithelium, leading to development of cholangiocarcinoma. These complications can occur even after restoration of immune function with HAART and improvement in CD4 count, pointing to the fact that the biliary dysplasia associated with AIDS cholangiopathy is irreversible and refractory to HAART-induced immune restoration[61-63].

CONCLUSION

Clearly, there is still much to be learned regarding AIDS cholangiopathy, particularly with its epidemiology, natural history, and determinants of pathology. While proper diagnosis of this disease has been well described and refined over the years, efficacious treatment methods for improving both symptomatic and pathologic processes, as well as preventing grave complications, still leave much to be desired. Hopefully, increased awareness of AIDS cholangiopathy through review articles such as this, will lead to further studies and better treatment options for afflicted patients, across both developed and developing countries, in the near future.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: December 25, 2017

First decision: January 4, 2018

Article in press: February 1, 2018

P- Reviewer: Akbulut S, Waheed Y S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

Maliha Naseer, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Francis E Dailey, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Alhareth Al Juboori, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Sami Samiullah, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Veysel Tahan, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States. tahanv@health.missouri.edu.

References

- 1.Fettig J, Swaminathan M, Murrill CS, Kaplan JE. Global epidemiology of HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on “Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades”. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2:e000227. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ, Holmberg SD. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, Kowalska JD, de Wit S, Law M, el Sadr W, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet. 2014;384:241–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puri P, Kumar S. Liver involvement in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:260–273. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaspar MB, Sterling RK. Mechanisms of liver disease in patients infected with HIV. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4:e000166. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2017-000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hessamfar-Bonarek M, Morlat P, Salmon D, Cacoub P, May T, Bonnet F, Rosenthal E, Costagliola D, Lewden C, Chêne G; Mortalité 2000 & 2005 Study Groups. Causes of death in HIV-infected women: persistent role of AIDS. The ‘Mortalité 2000 & 2005’ Surveys (ANRS EN19) Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:135–146. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Housset C, Lamas E, Courgnaud V, Boucher O, Girard PM, Marche C, Brechot C. Presence of HIV-1 in human parenchymal and non-parenchymal liver cells in vivo. J Hepatol. 1993;19:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80579-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdalian R, Heathcote EJ. Sclerosing cholangitis: a focus on secondary causes. Hepatology. 2006;44:1063–1074. doi: 10.1002/hep.21405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitlik SD, Fainstein V, Garza D, Guarda L, Bolivar R, Rios A, Hopfer RL, Mansell PA. Human cryptosporidiosis: spectrum of disease. Report of six cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:2269–2275. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350120059015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarda LA, Stein SA, Cleary KA, Ordóñez NG. Human cryptosporidiosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1983;107:562–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margulis SJ, Honig CL, Soave R, Govoni AF, Mouradian JA, Jacobson IM. Biliary tract obstruction in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:207–210. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-2-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneiderman DJ. Hepatobiliary abnormalities of AIDS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1988;17:615–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cello JP. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome cholangiopathy: spectrum of disease. Am J Med. 1989;86:539–546. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enns R. AIDS cholangiopathy: “an endangered disease”. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2111–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, Wood R, Laurent C, Sprinz E, Seyler C, Bangsberg DR, Balestre E, Sterne JA, May M, Egger M; Antiretroviral Therapy in Lower Income Countries (ART-LINC) Collaboration; ART Cohort Collaboration (ART-CC) groups. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleming AF. Opportunistic infections in AIDS in developed and developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84 Suppl 1:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90446-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow BJ, Anders K, Layfield LJ, Steinsapir KD, Gitnick GL, Lewin KJ. Clinical and pathologic findings of the liver in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:582–588. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/83.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cello JP. Gastrointestinal tract manifestations of AIDS. In: Sande MA, volberding PA, editors. The medical management of AIDS. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company;; 1997. pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Angelis C, Mangone M, Bianchi M, Saracco G, Repici A, Rizzetto M, Pellicano R. An update on AIDS-related cholangiopathy. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2009;55:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Y, Chin K, Mishriki YY. AIDS Cholangiopathy in an Asymptomatic, Previously Undiagnosed Late-Stage HIV-Positive Patient from Kenya. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:465895. doi: 10.4061/2011/465895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcox CM, Mönkemüller KE. Hepatobiliary diseases in patients with AIDS: focus on AIDS cholangiopathy and gallbladder disease. Dig Dis. 1998;16:205–213. doi: 10.1159/000016868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squire SA, Ryan U. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Africa: current and future challenges. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:195. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter PR, Nichols G. Epidemiology and clinical features of Cryptosporidium infection in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:145–154. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.145-154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen XM, LaRusso NF. Mechanisms of attachment and internalization of Cryptosporidium parvum to biliary and intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:368–379. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Hara SP, Small AJ, Gajdos GB, Badley AD, Chen XM, Larusso NF. HIV-1 Tat protein suppresses cholangiocyte toll-like receptor 4 expression and defense against Cryptosporidium parvum. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1195–1204. doi: 10.1086/597387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf TE, Baron TH. AIDS Cholangiopathy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pol S, Romana CA, Richard S, Amouyal P, Desportes-Livage I, Carnot F, Pays JF, Berthelot P. Microsporidia infection in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus and unexplained cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:95–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301143280204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheikh RA, Prindiville TP, Yenamandra S, Munn RJ, Ruebner BH. Microsporidial AIDS cholangiopathy due to Encephalitozoon intestinalis: case report and review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2364–2371. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walther Z, Topazian MD. Isospora cholangiopathy: case study with histologic characterization and molecular confirmation. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1342–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapelusznik L, Arumugam V, Caplivski D, Bottone EJ. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as AIDS cholangiopathy. Mycoses. 2011;54:262–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keaveny AP, Karasik MS. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic infections in AIDS: Part II. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1998;12:451–456. doi: 10.1089/apc.1998.12.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devarbhavi H, Sebastian T, Seetharamu SM, Karanth D. HIV/AIDS cholangiopathy: clinical spectrum, cholangiographic features and outcome in 30 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1656–1660. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das CJ, Sharma R. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: AIDS cholangiopathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:774. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benhamou Y, Caumes E, Gerosa Y, Cadranel JF, Dohin E, Katlama C, Amouyal P, Canard JM, Azar N, Hoang C. AIDS-related cholangiopathy. Critical analysis of a prospective series of 26 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1113–1118. doi: 10.1007/BF01295729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes A, Blanshard C, Gazzard B. Natural history of AIDS related sclerosing cholangitis: a study of 20 cases. Gut. 1993;34:116–121. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daly CA, Padley SP. Sonographic prediction of a normal or abnormal ERCP in suspected AIDS related sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:618–621. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Da Silva F, Boudghene F, Lecomte I, Delage Y, Grange JD, Bigot JM. Sonography in AIDS-related cholangitis: prevalence and cause of an echogenic nodule in the distal end of the common bile duct. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:1205–1207. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.6.8498216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carucci LR, Halvorsen RA. Abdominal and pelvic CT in the HIV-positive population. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:631–642. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouche H, Housset C, Dumont JL, Carnot F, Menu Y, Aveline B, Belghiti J, Boboc B, Erlinger S, Berthelot P. AIDS-related cholangitis: diagnostic features and course in 15 patients. J Hepatol. 1993;17:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bilgin M, Balci NC, Erdogan A, Momtahen AJ, Alkaade S, Rau WS. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic MRI and MRCP findings in patients with HIV infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:228–232. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tonolini M, Bianco R. HIV-related/AIDS cholangiopathy: pictorial review with emphasis on MRCP findings and differential diagnosis. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collazos J, Mayo J, Martínez E, Callejo A, Blanco I. Celiac plexus block as treatment for refractory pain related to sclerosing cholangitis in AIDS patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:47–49. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoepelman AI. Current therapeutic approaches to cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:871–880. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White AC Jr, Chappell CL, Hayat CS, Kimball KT, Flanigan TP, Goodgame RW. Paromomycin for cryptosporidiosis in AIDS: a prospective, double-blind trial. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:419–424. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossignol JF, Ayoub A, Ayers MS. Treatment of diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium parvum: a prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Nitazoxanide. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:103–106. doi: 10.1086/321008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oku T, Maeda M, Waga E, Wada Y, Nagamachi Y, Fujita M, Suzuki Y, Nagashima K, Niitsu Y. Cytomegalovirus cholangitis and pancreatitis in an immunocompetent patient. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:987–992. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1683-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molina JM, Oksenhendler E, Beauvais B, Sarfati C, Jaccard A, Derouin F, Modaï J. Disseminated microsporidiosis due to Septata intestinalis in patients with AIDS: clinical features and response to albendazole therapy. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:245–249. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deodhar L, Maniar JK, Saple DG. Cyclospora infection in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:404–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lagrange-Xélot M, Porcher R, Sarfati C, de Castro N, Carel O, Magnier JD, Delcey V, Molina JM. Isosporiasis in patients with HIV infection in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era in France. HIV Med. 2008;9:126–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan MF, Koch J, Cello JP. Ursodeoxycholic acid for symptomatic AIDS associated cholangiopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:103. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castiella A, Iribarren JA, López P, Arrizabalaga J, Rodríguez F, von Wichmann MA, Arenas JI. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of AIDS-associated cholangiopathy. Am J Med. 1997;103:170–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imai K, Misawa K, Matsumura T, Fujikura Y, Mikita K, Tokoro M, Maeda T, Kawana A. Progressive HIV-associated Cholangiopathy in an HIV Patient Treated with Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. Intern Med. 2016;55:2881–2884. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahajani RV, Uzer MF. Cholangiopathy in HIV-infected patients. Clin Liver Dis. 1999;3:669–684, x. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cello JP, Chan MF. Long-term follow-up of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography sphincterotomy for patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome papillary stenosis. Am J Med. 1995;99:600–603. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cordero E, López-Cortés LF, Belda O, Villanueva JL, Rodríguez-Hernández MJ, Pachón J. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related cryptosporidial cholangitis: resolution with endobiliary prosthesis insertion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:534–535. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hessol NA, Koblin BA, van Griensven GJ, Bacchetti P, Liu JY, Stevens CE, Coutinho RA, Buchbinder SP, Katz MH. Progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection among homosexual men in hepatitis B vaccine trial cohorts in Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco, 1978-1991. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1077–1087. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ducreux M, Buffet C, Lamy P, Beaugerie L, Fritsch J, Choury A, Liguory C, Longuet P, Gendre JP, Vachon F. Diagnosis and prognosis of AIDS-related cholangitis. AIDS. 1995;9:875–880. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ko WF, Cello JP, Rogers SJ, Lecours A. Prognostic factors for the survival of patients with AIDS cholangiopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2176–2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Datta J, Shafi BM, Drebin JA. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma developing in the setting of AIDS cholangiopathy. Am Surg. 2013;79:321–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Charlier C, Lecuit M, Furco A, Estavoyer JM, Lafeuillade A, Dupont B, Lortholary O, Viard JP. Cholangiocarcinoma in HIV-Infected patients with a history of Cholangitis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:253–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mangeya N, Mafukidze AT, Pascoe M, Mbuwayesango B, Madziva D, Ndlovu N, Corbett EL, Miller RF, Ferrand RA. Cholangiocarcinoma presenting in an adolescent with vertically acquired HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:717–718. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]