Abstract

The actin cytoskeleton is a crucial regulator of the intestinal mucosal barrier, controlling the assembly and function of epithelial adherens and tight junctions (AJs and TJs). Junction-associated actin filaments are dynamic structures that undergo constant turnover. Members of the actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin protein family play key roles in actin dynamics by mediating filament severing and polymerization. We examined the roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in regulating the structure and functions of AJs and TJs in the intestinal epithelium. Knockdown of either ADF or cofilin-1 by RNA interference increased the paracellular permeability of human colonic epithelial cell monolayers to small ions. Additionally, cofilin-1, but not ADF, depletion increased epithelial permeability to large molecules. Loss of either ADF or cofilin-1 did not affect the steady-state morphology of AJs and TJs but attenuated de novo junctional assembly. The observed defects in AJ and TJ formation were accompanied by delayed assembly of the perijunctional filamentous actin belt. A total loss of ADF expression in mice did not result in a defective mucosal barrier or in spontaneous gut inflammation. However, ADF-null mice demonstrated increased intestinal permeability and exaggerated inflammation during dextran sodium sulfate–induced colitis. Our findings demonstrate novel roles for ADF and cofilin-1 in regulating the remodeling and permeability of epithelial junctions, as well as the role of ADF in limiting the severity of intestinal inflammation.

The actin cytoskeleton is a key regulator of intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Differentiated enterocytes possess elaborate apical filamentous (F)-actin structures that include the circumferential F-actin belt, F-actin bundles supporting microvilli, and the terminal web.1, 2 These structures play a number of essential functions, including the establishment of apicobasal cell polarity, as well as the regulation of ion transport and epithelial permeability. The regulation of the epithelial barrier represents one of the most important functions of the actin cytoskeleton.3, 4 Actin filaments control the assembly and function of two major epithelial junctional complexes, namely, adherens junctions (AJs) and tight junctions (TJs). AJs form the initial contacts between adjacent epithelial cells by engaging transmembrane adhesive proteins such as E-cadherin and nectins.5, 6, 7 TJs seal the paracellular space and generate a charge-specific barrier for the free diffusion of ions and other molecules by assembling claudin-based, membrane-embedded fibrils associated with other integral and cytoplasmic proteins.8, 9, 10 Actin filaments can interact with several actin-binding proteins located on the cytosolic face of AJs and TJs. These interactions with the actin cytoskeleton cluster and stabilize junctional complexes and regulate their remodeling during the disruption and assembly of epithelial cell–cell contacts.3, 7, 11, 12, 13

Actin filaments associated with epithelial junctions are dynamic structures that undergo constant remodeling (disassembly and reassembly).14, 15, 16 Such F-actin dynamics are essential for the stability and rearrangement of AJs and TJs and are regulated by a large number of accessory, signaling, and motor proteins.3, 4, 7, 13, 17, 18 Members of the actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin protein family act as crucial regulators of actin filament dynamics.19, 20 These small (18 kDa) actin-binding proteins are known to control the actin cytoskeleton via several mechanisms. A major activity of ADF and cofilin proteins involves the severing of existing filaments, thus producing free barbed ends for subsequent filament nucleation.21, 22 This event promotes actin-related protein 2/3–dependent actin polymerization because actin-related protein 2/3–dependent branches are much more stable on newly polymerized actin filaments than on “older” filaments.23 Furthermore, ADF and cofilin can directly nucleate actin filaments24 and regulate filament bundling and contractility by inhibiting the interaction between F-actin and the myosin II motor.25 Mammalian cells express three relevant homologous proteins: ADF (also known as destrin), cofilin-1, and cofilin-2. Cofilin-1 is ubiquitously expressed in nonmuscle tissues, whereas cofilin-2 is a muscle-specific isoform. ADF is not as abundant as is cofilin-1, but it is enriched in different epithelia and in the brain.26, 27

The physiological functions of ADF and cofilin-1 involve the regulation of various actin-dependent processes such as cell motility, cytokinesis, vesicle trafficking, and cell survival.21, 28, 29, 30, 31 It is well-documented that ADF and cofilin activation accompanies the disruption of epithelial and endothelial barriers in vitro18, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 and in vivo.37, 38 However, the existing evidence regarding ADF- and cofilin-dependent regulation of epithelial junctions in different experimental systems remains sparse and controversial. For example, dysfunction of twinstar, a Drosophila homologue of ADF and cofilin, impairs the formation of AJs and the morphogenesis of the retinal epithelium.39, 40 Furthermore, the loss of cofilin-1 disrupts the cadherin-dependent adhesion between different epithelial cell layers during gastrulation in zebrafish.41 In mammalian systems, cofilin activation accelerates TJ assembly in cultured renal epithelial cells.42 On the other hand, the deletion of cofilin-1 promotes the abnormal assembly of basal TJs in the mouse neural plate.43 Our recent study demonstrated that actin-interacting protein 1, a known accelerator of ADF- and cofilin-dependent actin filament severing, controls the assembly and function of AJs and TJs in human intestinal epithelial cells.44 The mammalian gut is one of the few organs with high expression of both ADF and cofilin-1.26, 27 However, the roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in the regulation of the intestinal epithelial barrier remain largely unexplored. This study provides the first evidence that ADF and cofilin-1 have unique and redundant functions relating to the control of the permeability and remodeling of intestinal epithelial junctions in vitro, and that ADF is an essential suppressor of intestinal mucosal inflammation in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Other Reagents

The following primary monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) were used for detecting cytoskeletal, junctional, and leukocyte proteins: anti–p120-catenin, E-cadherin, Ly6, and CD4 mAbs (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); anti–E-cadherin pAb (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); anti-occludin and zonula occludens protein 1 pAbs and mAbs, anti–claudin-1 and claudin-3 pAbs, and claudin-4 mAb (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA); anti–total actin (clone C4) mAb (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA); anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (14C10) mAb (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); anti–β-catenin and ADF pAbs, and cofilin-1 mAb (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); anti–protein kinase C ζ (C-20) pAb (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX); anti-F4/80 mAb (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and donkey anti-goat, Alexa Fluor 555–conjugated donkey anti-mouse and goat anti-rat secondary antibodies, and Alexa Fluor 488– and Alexa Fluor 555–labeled phalloidin were obtained from Life Technologies. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were acquired from Bio-Rad Laboratories. Latrunculin (Lat) B was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cells

HT-29 (cl.F8) (a gift from Dr. Judith M. Ball, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) and Caco2-BBE (ATCC, Manassas, VA) human colonic epithelial cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, HEPES, nonessential amino acids, and antibiotics. Cells were grown in T75 flasks, and for immunolabeling experiments were seeded on either collagen-coated permeable polycarbonate filters (0.4-μm pore size; Costar, Cambridge, MA) or on collagen-coated coverslips. For biochemical studies, cells were cultured on 6-well plates. HT-29 cells were further differentiated by the addition of 2 mmol/L sodium butyrate to the cell culture medium.

Animals

A.BY H2bc H2-t18f/SnJ-Dstncorn1/J (Dstncorn1, ADF null) and A.BY H2bc H2-t18f/SnJ (wild-type control) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, MA). Initial breading pairs of control A.BY mice were provided by Dr. Sakae Ikeda (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI). The animal colony was established and maintained under pathogen-free conditions in the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center vivarium. Standard feed and tap water were available ad libitum. The mouse room was on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7 am). At the time of the experiments, mice weighed 18 to 25 g, and there was no meaningful difference between the body masses of mice of different genotypes. All procedures were conducted using a protocol (AD10000458) approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of Stable Cell Lines with shRNA-Mediated ADF and Cofilin-1 Knockdown

HT-29 and Caco-2BBE cell lines with stable shRNA-mediated knockdown of either cofilin-1 or ADF were generated using the Thermo Scientific Open Biosystems Expression Arrest GIPZ Lentiviral shRNAmir system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, Huntsville, AL). To prepare shRNA-containing lentivirus, 293FT cells were transfected with 21 μg of pGIPZ shRNA plasmid and 21 μg of the packaging vectors (14 μg of pCD/NL-BH*DDD and 7 μg of pLTR-G; Addgene, Cambridge, MA). Cell culture medium containing lentiviral particles was collected at 48 hours after transfection and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. HT-29 and Caco-2BBE cells were transduced with either cofilin-1 or ADF shRNA-containing lentiviral particles, and stable cell lines were selected using puromycin (5 and 15 μg/mL for HT-29 and Caco-2BBE cells, respectively). Two different shRNA sequences specific to either cofilin-1 (cat. nos. V2LHS_405913 and 342369) or ADF (V2LHS_336587 and 336589) were used for generating stable cell lines. A nonsilencing shRNA plasmid (RHS4346), lacking complementarity to any human gene, was used as a control.

Transient knockdown of ADF and cofilin-1 in HT-29 and Caco-2BBE cells was performed using Dharmacon siGENOME siRNA duplexes (GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO): cofilin-1 siRNA duplex 1 (cat. no. D-012707-01), cofilin-1 duplex 2 (D-012707-04), ADF siRNA duplex 1 (D-012303-01), and ADF siRNA duplex 2 (D-012303-04). Cofilin-1 duplex 1 or ADF duplex 1 were used for transient knockdown of individual proteins in HT-29 cells. A dual cofilin-1 and ADF knockdown was performed using two different combinations of Dharmacon siGENOME siRNA duplexes: cofilin-1 siRNA duplex 1 plus ADF siRNA duplex 1, and cofilin-1 siRNA duplex 2 plus ADF siRNA duplex 2. Dharmacon nontargeting siRNA duplex 2 was used as control. Cells were transfected using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (GE Dharmacon) with a final siRNA concentration of 50 nmol/L, as previously described.45, 46 Cells were utilized for experiments on days 3 and 4 after transfection.

Calcium Switch and Latrunculin B Test

To deplete extracellular calcium, HT-29 cell monolayers were washed twice with Eagle's minimum essential medium for suspension culture supplemented with 5 μmol/L CaCl2, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 14 mmol/L NaHCO3, and 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (designated here as S-MEM) and incubated overnight in S-MEM at 37°C. To induce junctional reassembly, the cells were returned to normal cell culture medium with 2 mmol/L butyrate for the indicated times. For the Lat B test, control or ADF- or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were plated on membrane filters, and 5 days after plating were subjected to 4 hours of treatment with either 1 μmol/L Lat B or vehicle. Subsequently, Lat B was washed out with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, and the cells were allowed to recover in normal medium for 1 hour before fixation.

Induction and Characterization of Dextran Sulfate Sodium–Induced Colitis

Experimental colitis was induced in 8- to 10-week-old ADF-null and A.BY wild-type mice by administering 5% (w/v) solution of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; molecular weight, 40 kDa; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) in drinking water, ad libitum. Control animals received regular water. Both male and female mice were used roughly equally in this study. The animals were weighed daily and monitored for signs of intestinal inflammation. The disease activity index was calculated as previously described, based on the extent of body weight loss, stool consistency, and intestinal bleeding.47 On day 8 of DSS administration, animals were euthanized, and their colonic tissue was separated into several segments. The samples were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, frozen in liquid nitrogen, or embedded in OCT and snap frozen for subsequent histological and biochemical examination. Paraformaldehyde-fixed samples were paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The tissue injury index was calculated based on microscopic examination of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections, as previously described.48 The index represents the sum of individual scores reflecting epithelial erosion, leukocyte infiltration, submucosal edema, and alteration to the muscular layer.

Measurement of Epithelial Barrier Permeability in Vitro and in Vivo

Transepithelial electrical resistance of cultured epithelial cell monolayers was measured using an EVOMX volt-ohm meter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The resistance of cell-free collagen-coated filters was subtracted from each experimental point. An in vitro dextran flux assay was performed as previously described.45 Briefly, HT-29 cell monolayers growing on transwell filters were apically exposed to 1 mg/mL of fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled dextran (either 4000 or 40,000 Da) in HEPES-buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). After 60 minutes of incubation, HBSS samples were collected from the lower chamber, and fluorescein isothiocyanate fluorescence intensity was measured using a Victor3 V plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 544 nm, respectively. After subtraction of the fluorescence of dextran-free HBSS, relative intensity was calculated using Prism 5.03 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). An in vivo permeability assay was performed in ADF-null and wild-type animals receiving either 5% DSS or water for 8 days. Animals were gavaged with 4000-Da fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled dextran (60 mg/100 g body weight) using a 1-mL insulin syringe and a standard curved gavage needle. Three hours later, animals were euthanized, and blood was collected in Microtainer tubes (BD Biosciences) via cardiac puncture. Blood serum was obtained by centrifugation, and the fluorescence intensity of the serum samples was measured using a plate reader. The fluorescence of dextran-free serum was subtracted from each experimental value.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cultured human epithelial cells or mouse colonic segments were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [20 mmol/L Tris, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L EGTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100 (TX-100), and 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4] containing protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich). The protein concentration of total lysates and cellular fractions was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit. Samples were diluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and boiled. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was conducted using standard protocols, with an equal amount of total protein loaded per lane (10 or 20 μg), followed by immunoblot analysis on nitrocellulose membrane. Protein expression was quantified via densitometry using ImageJ software version 1.46 (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). Data are presented as normalized values, with expression values in control shRNA/siRNA-treated groups defined as 100%.

G/F-Actin Fractionation

Quantification of G- and F-actin was performed by TX-100 fractionation of cellular actin, as previously described.49 Briefly, epithelial monolayers were washed with HBSS, and G-actin was extracted with gentle shaking for 5 minutes at room temperature in cytoskeleton stabilization buffer (10 mmol/L MES, 140 mmol/L KCl, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L EGTA, 280 mmol/L sucrose, pH 6.1) supplemented with 0.5% TX-100, proteinase inhibitor cocktail, and 1 μg/mL phalloidin to prevent filament disassembly. The TX-100–soluble G-actin fraction was mixed with an equal volume of 2× SDS sample buffer and boiled. Cells were then briefly washed with HBSS buffer, and the TX-100–insoluble F-actin fraction was collected by scraping cells in double the volume of SDS sample buffer, with subsequent homogenizing and boiling. The amount of actin in each fraction was determined by gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis, as described in Immunoblot Analysis.

Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from colonic segments of ADF-null and wild-type mice using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), followed by DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences of primers that were used for amplifying the mouse housekeeping gene Gapdh, and selected cytokines and chemokines, are presented in the Table 1. The threshold cycle number (Ct) for specific genes of interest, and for the housekeeping gene, was determined based on the amplification curve representing a plot of the fluorescent signal intensity versus the cycle number. Relative expression of each gene was calculated by a comparative Ct method that is based on the inverse proportionality between Ct and the initial template concentration (2−ΔΔCt), as previously described.50 This method is based on two-step calculations of ΔCt = Cttarget gene − CtGapdh and ΔΔCt = ΔCte − ΔCtc, where index e refers to the sample from any DSS or water-treated ADF-null or wild-type mouse, and index c refers to a sample from a water-treated wild-type animal assigned as an internal control.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences for Quantitative Real-Time Reverse-Transcription PCR

| Gene | GenBank Accession no. | Direction | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | NM008084.3 | Forward | 5′-CATGTTTGTGATGGGTGTGAACCA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGTGATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCAT-3′ | ||

| TNFA | BC117057.1 | Forward | 5′-ACGGCATGGATCTCAAAGACAACC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGAGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACGGT-3′ | ||

| IL1 | NM_008361.4 | Forward | 5′-TGGAGAGTGTGGATCCCAAGCAAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGTCCTGACCACTGTTGTTTCCCA-3′ | ||

| IL6 | BC132458.1 | Forward | 5′-ATCCAGTTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CATGTTTGTGATGGGTGTGAACCA-3′ | ||

| IL10 | NM_010548.2 | Forward | 5′-GGTTGCCAAGCCTTATCGGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACCTGCTCCACTGCCTTGCT-3′ | ||

| IL12 | NM_008352.2 | Forward | 5′-AGACCCTGCCCATTGAACTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAAGCTGGTGCTGTAGTTCTCATATTT-3′ | ||

| IFNG | NM_008337.4 | Forward | 5′-GCTCTGAGACAATGAACGCTAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTCTAGGCTTTCAATGACTGTGC-3′ | ||

| CCL3 | NM_011337.2 | Forward | 5′-CCAAGTCTTCTCAGCGCCAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GAATCTTCCGGCTGTAGGAGAAG-3′ | ||

| CCL11 | NM_011330.3 | Forward | 5′-GAATCACCAACAACAGATGCAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ATCCTGGACCCACTTCTTCTT-3′ | ||

| MIP2 | NM_009140.2 | Forward | 5′-GGCAAGGCTAACTGACCTGGAAAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ACAGCGAGGCACATCAGGTACGA-3′ |

GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo.

Immunofluorescence Labeling, TUNEL Assay, and Confocal Microscopy

Cultured colonic epithelial cell monolayers were fixed and permeabilized with 100% methanol at −20°C, and with 4% paraformaldehyde/0.5% TX-100 at room temperature, to visualize junctional proteins and actin filaments, respectively. Frozen sections of mouse colon were fixed with either 95% ethanol to visualize junctional proteins and leukocyte markers or with 4% paraformaldehyde for F-actin and ADF labeling. Fixed samples were blocked for 60 minutes in HBSS containing 1% bovine serum albumin, followed by a 60-minute incubation with primary antibodies. Samples were then washed and incubated with Alexa dye–conjugated secondary antibodies for 60 minutes, rinsed with blocking buffer, and mounted on slides with ProLong Antifade mounting reagent with or without DAPI (Life Technologies). F-actin was visualized by 60-minute labeling with Alexa 555–labeled phalloidin. A terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed using an ApopTag Fluorescein in Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (EMD Millipore) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled cell monolayers and tissue sections were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 700 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC, Peabody, MA). The Alexa Fluor 488 and 555 signals were acquired sequentially in frame-interlace mode to eliminate crosstalk between channels. Images were processed using Zen 2012 software version 8.0.0.273 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy LLC) and Adobe Photoshop version 13.0.1 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The images shown are representative of at least three experiments, with multiple images taken per slide. To quantify AJ and TJ reassembly in cultured cell monolayers, signal intensity was measured after the selection of a rectangular area at the cellular border. Six to seven fields with cells were randomly selected from each sample, and the total junctional length, in pixels of each field, was measured using ImageJ software. To quantify the results of tissue TUNEL assay, T-cell marker (CD4), and macrophage marker (F4/80) labeling, signal intensity was measured on the mucosal surface and crypt areas of the sample from each animal. Mean values were calculated by averaging signal intensities obtained from the tissue samples of six different animals from each experimental group. The intensity of Ly6 labeling was measured only in the colonic crypt region, where the labeling intensity was much higher as compared to that at the colonic surface.

Epithelial Cyst Formation in Matrigel

A 3D epithelial cyst assay was performed as previously described.45, 51 Briefly, control and ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted Caco-2 cells were trypsinized, resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, and mixed with a growth-factor–reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Matrigel-embedded cells were plated on 8-chamber glass slides (BD Biosciences). Cysts were allowed to form for 72 hours at 37°C, with 1 μmol/L forskolin to enhance cyst lumen formation. Cysts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% TX-100, and stained using a standard protocol; blocking and primary and secondary antibody incubations were performed for 2 hours, and all washing steps were performed for 30 minutes. For quantitative analysis, cyst images were acquired at low resolution, and the total number of cysts and the number of cysts within the lumen were counted manually.

Statistical Analysis

Numerical values from individual experiments were pooled and are expressed as means ± SEM throughout. The values obtained were compared using a two-tailed Student's t-test, with statistical significance assumed at P < 0.05.

Results

Loss of ADF and Cofilin-1 Increases the Permeability and Impairs the Assembly of Apical Junctions in Intestinal Epithelial Cell Monolayers

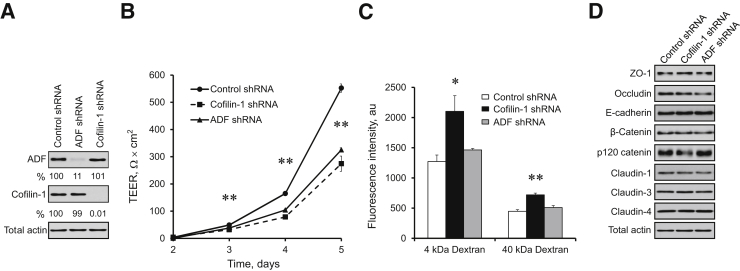

To investigate the roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in the regulation of epithelial junctions, we generated stable cell lines with selective shRNA-mediated knockdown of these proteins in HT-29 cl.F8 human colonic epithelial cells. HT-29 cl.F8 is a differentiated clone of HT-29 cells that is characterized by distinct TJs and tight paracellular barriers.52 We further accelerated TJ assembly and barrier development in these cells by differentiating them in the presence of butyric acid. ADF- or cofilin-1–specific shRNAs efficiently depleted the targeted proteins in HT-29 cells (Figure 1A). Importantly, the loss of ADF did not affect cofilin-1 expression and vice versa, which allows for the examining of the specific functions of these closely related actin regulators.

Figure 1.

Depletion of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 attenuates the establishment of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Stable knockdown of either ADF or cofilin-1 was performed in HT-29 cl.F8 colonic epithelial cells by transfection with shRNA plasmids. A: The efficiency and specificity of each knockdown was examined by immunoblot analysis. B and C: The permeability of control, ADF, and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers was examined by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) and transepithelial fluxes of fluoresceinated dextrans. D: The expression of key adherens and tight junction proteins in polarized cell monolayers was examined by immunoblot analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.005. ZO, zonula occludens.

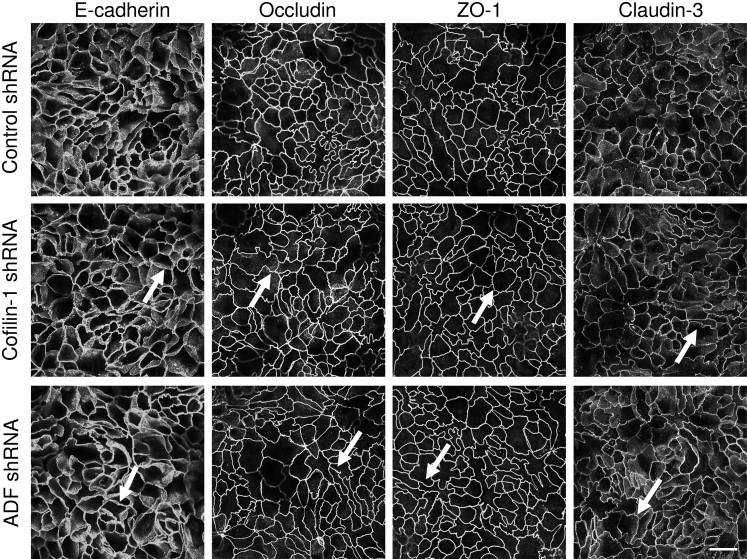

Loss of either ADF or cofilin-1 attenuated the development of transepithelial electrical resistance, thereby indicating increased paracellular permeability to small ions (Figure 1B). In contrast, only cofilin-1 depletion significantly increased the transepithelial flux of large molecules such as fluoresceinated dextran (Figure 1C). Interestingly, dual siRNA-mediated ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown in HT-29 cells show an additive decrease in transepithelial electrical resistance as compared to individual depletion of ADF or cofilin-1 (Supplemental Figure S1). Neither ADF nor cofilin-1 knockdown affected the expression of key AJ and TJ proteins (Figure 1D). Moreover, immunofluorescence labeling demonstrated that selective depletion of these actin regulators did not alter the normal “chicken wire” morphology of AJs and TJs in steady-state well-differentiated HT-29 cell monolayers (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) or cofilin-1 does not affect the steady-state integrity of epithelial apical junctions. Control, ADF-depleted, or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were cultured for 7 days on semipermeable membrane filters. Cells were fixed, immunolabeled for different adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) proteins, and examined by confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate intact AJs and TJs in ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.

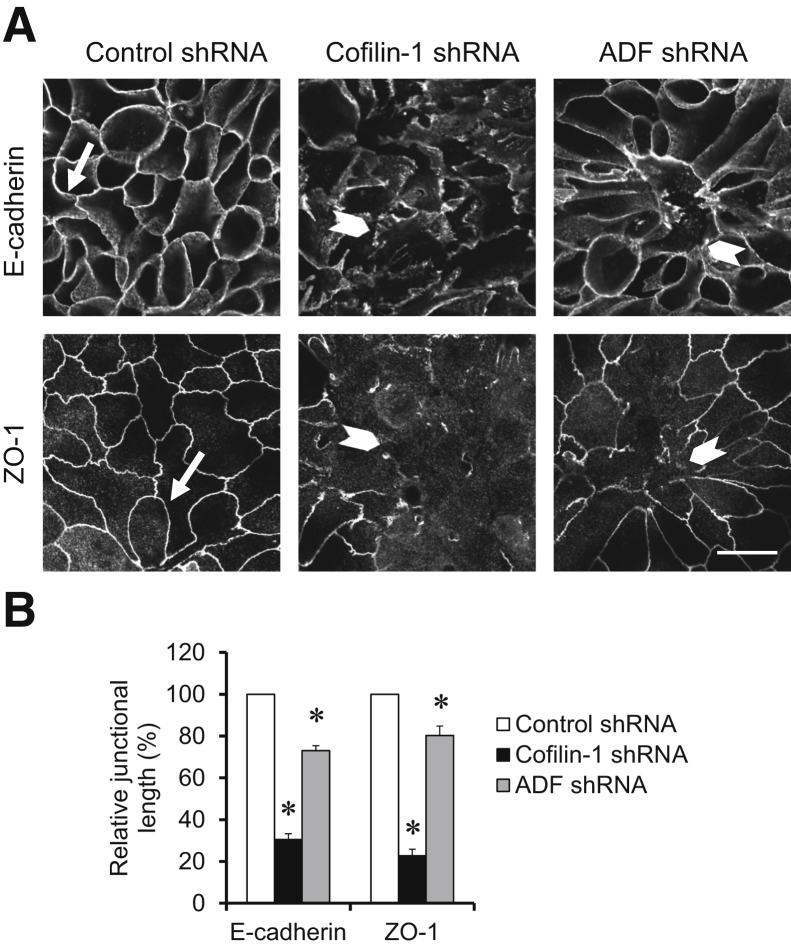

Next, we investigated whether ADF or cofilin-1 controls de novo the assembly of epithelial junctions by using a classic “calcium switch” assay. This assay involves the orchestrated restoration of AJs and TJs in confluent stationary epithelial cell monolayers, thereby eliminating any possible indirect, cell motility–dependent effects of actin regulators.53, 54 Control, ADF-depleted, and cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cell monolayers were subjected to overnight extracellular calcium depletion to disassemble existing AJs and TJs. Junctional reassembly was induced by the reintroduction of calcium to the cell culture medium. Interestingly, this process occurs at a slower rate in HT-29 cells as compared to T84 and SK-CO15 colonic epithelial cells33, 54 and requires about 30 hours for complete restoration of E-cadherin–based AJs and zonula occludens protein 1–based or occludin-based TJs (Figure 3, A and B). Loss of either cofilin-1 or ADF attenuated junctional assembly during either 24 hours (Supplemental Figure S3) or 30 hours (Figure 3) of calcium repletion. Interestingly, cofilin-1 depletion caused attenuation of AJ and TJ recovery that was more pronounced compared to that of ADF knockdown (Figure 3B). Together, these findings demonstrate the essential roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in regulating barrier properties and junctional assembly in model intestinal epithelial cell monolayers.

Figure 3.

Down-regulation of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 attenuates the reassembly of epithelial junctions. Control, ADF-depleted, and cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were subjected to overnight calcium depletion to disassemble apical junctions, followed by calcium restoration for 30 hours to induce adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) reassembly. Cells were fixed and immunolabeled for AJ (E-cadherin) and TJ (zonula occludens protein 1) proteins. Representative images (A) and quantification of junctional length (B) are shown. Arrows indicate AJ and TJ reassembly in control cells. Arrowheads indicate the defects in junctional reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.

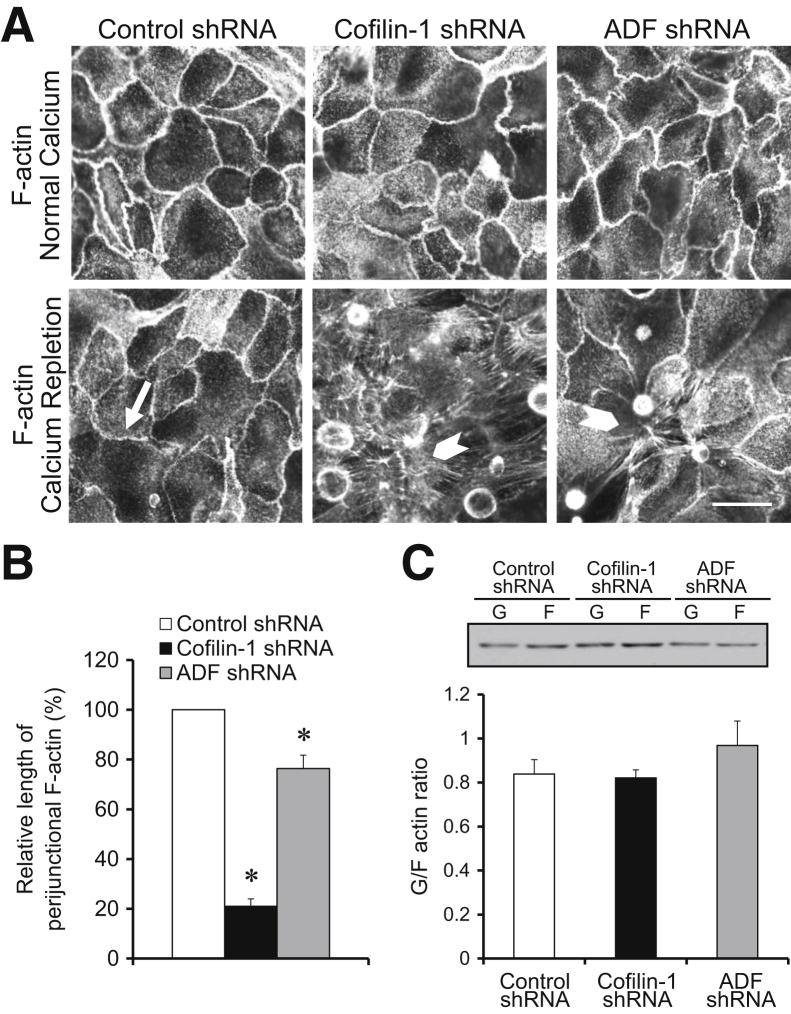

Depletion of ADF and Cofilin-1 Affects the Remodeling of the Perijunctional F-Actin Cytoskeleton

Because the cellular functions of ADF and cofilin-1 depend on the regulation of F-actin dynamics, depletion of these proteins most likely affects the assembly of epithelial junctions by altering the organization and/or dynamics of perijunctional actin filaments. Visualization of the actin cytoskeleton demonstrated that loss of either ADF or cofilin-1 did not alter the architecture of the perijunctional F-actin belt in steady-state HT-29 cell monolayers (Figure 4A). This finding is consistent with the lack of gross alteration in AJ and TJ structure (Figure 2). During calcium repletion of control HT-29 cells, formation of the perijunctional F-actin belt paralleled AJ and TJ reassembly (Figure 4A). Loss of either ADF or cofilin-1 significantly attenuated the reformation of junction-associated F-actin bundles (Figure 4, A and B); this effect was more pronounced in cofilin-1–depleted cells. Interestingly, loss of ADF or cofilin-1 did not impair the formation of basal stress fibers in calcium-repleted epithelial cells (Figure 4A). These data suggest that different mechanisms control the assembly of cytoskeletal structures supporting matrix adhesions and epithelial junctions. Biochemical fractionation permitting the determination of the polymerization status of total cellular actin showed that neither ADF nor cofilin-1 depletion significantly affected the G/F-actin ratio in HT-29 cell monolayers subjected to calcium switch (Figure 4C). The relatively slow dynamics of junctional reassembly in calcium-repleted HT-29 cell monolayers open the possibility that other mechanisms (eg, gene expression) could also be involved. Therefore, we investigated the roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in the more specific, actin-driven formation of epithelial junctions. This formation was achieved by using a Lat B test that involves depolymerization of preexisting F-actin with a G-actin–sequestering drug, Lat B,55 with subsequent reformation of actin filaments after Lat B washout.56 Incubation of HT-29 cells for 4 hours with 1 μmol/L Lat B resulted in complete AJ and TJ disassembly and disintegration of the perijunctional F-actin belt (data not shown). After Lat B washout, control HT-29 cells rapidly (within 1 hour) restored normal TJ structure and reassembled the perijunctional F-actin belt (Supplemental Figure S4). In contrast, either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion significantly attenuated post–Lat B assembly of the perijunctional cytoskeleton and the recovery of TJs (Supplemental Figure S4). These results suggest that ADF and cofilin-1 cooperate in the remodeling of epithelial junctions by controlling the assembly of junction-associated F-actin cytoskeleton.

Figure 4.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 impairs the reassembly of the perijunctional actin cytoskeleton. A and B: Polarized controls, ADF-depleted, or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cell monolayers were fixed either under steady-state conditions or after 30 hours of calcium repletion. The organization of the perijunctional F-actin belt was visualized by fluoresceinated phalloidin labeling. Arrow indicates complete reassembly of the perijunctional F-actin belt in control cells. Arrowheads show attenuation of perijunctional F-actin reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. C: The effects of ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown on the total amount of F-actin in calcium-repleted HT-29 cells were determined by G/F-actin fractionation. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

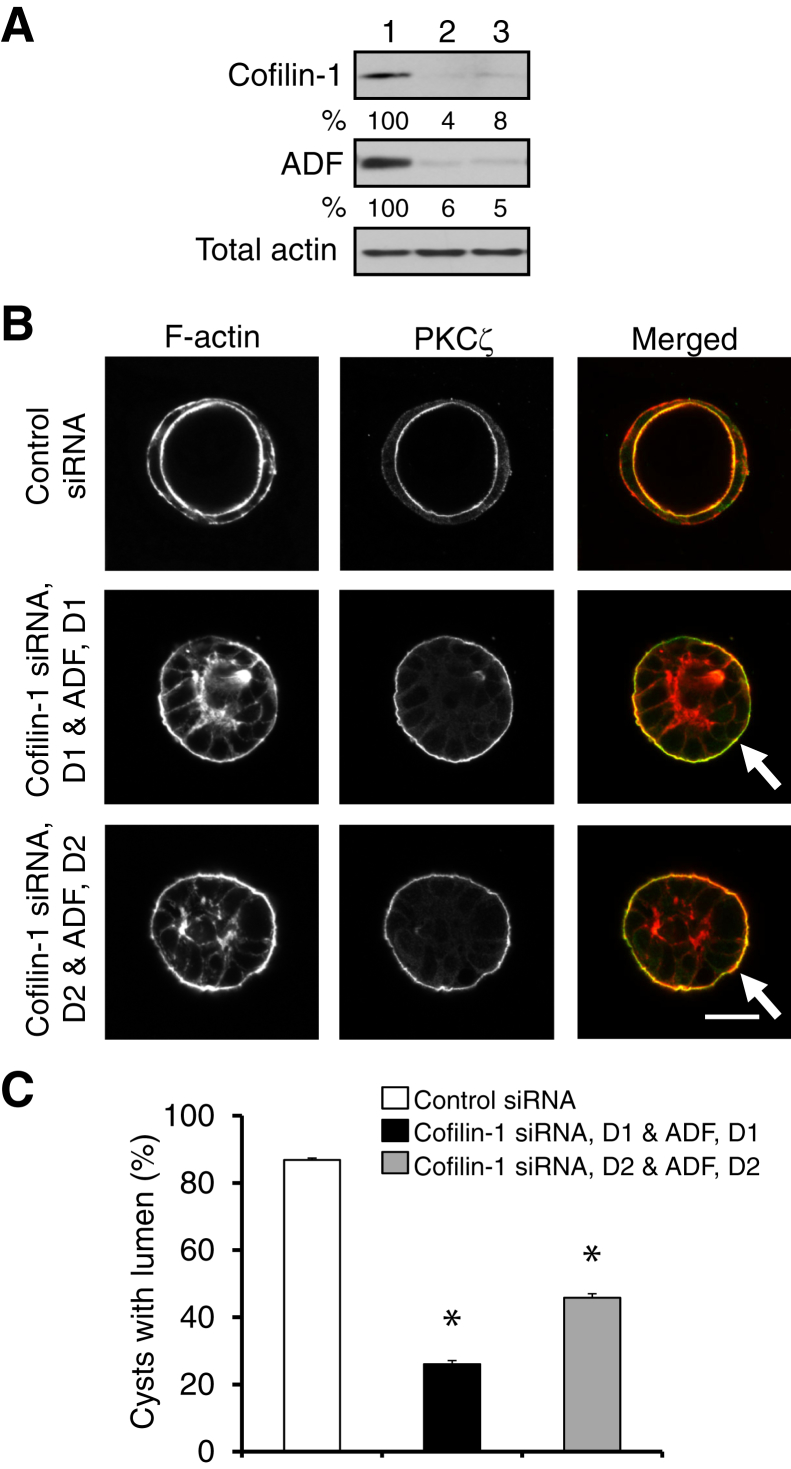

Dual Depletion of ADF and Cofilin-1 Inhibits 3D Epithelial Morphogenesis

Because AJ and TJ assembly represents a key step in epithelial morphogenesis, we next investigated the roles of ADF and cofilin-1 in the formation of intestinal epithelial spheroids growing in 3D space. These experiments were performed in Caco-2BBE colonic epithelial cells that, unlike HT-29 cells, form well-polarized 3D structures while growing in Matrigel.45, 51 Caco-2 cells with a specific stable depletion of either ADF or cofilin-1 (Supplemental Figure S5A) were embedded in Matrigel for 5 days, with subsequent microscopic analysis of the developed epithelial spheroids. More than 90% of control spheroids appeared as well-polarized cysts with a defined central lumen lined by thick F-actin bundles and displaying a marker of the apical plasma membrane, protein kinase C ζ (Supplemental Figure S5B). ADF depletion did not affect cyst formation, whereas selective cofilin-1 knockdown modestly decreased (by 17%) the number of lumen-possessing cysts (Supplemental Figure S5, B and C). The lack of vivid effects of individual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown on 3D epithelial morphogenesis most likely reflects a functional redundancy in these proteins. To test this hypothesis, we performed transient dual knockdowns by transfecting Caco-2 cells with two different combinations of ADF and cofilin-1–specific siRNA duplexes (Figure 5A). Such dual depletion dramatically impaired luminal morphogenesis in 3D cysts (Figure 5, B and C). Indeed, a significant fraction of ADF and cofilin-1 co-depleted cysts did not develop the central lumen and demonstrated mislocalization of protein kinase C ζ to the basal surface (Figure 5B). These results suggest that ADF and cofilin-1 play essential but redundant functions in regulating the early events of 3D intestinal epithelial morphogenesis.

Figure 5.

Dual knockdown of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 inhibits the formation of intestinal epithelial cysts. Caco-2 human colonic epithelial cells were transfected with either control siRNA or two combinations of ADF- and cofilin-1–specific siRNA duplexes (D1 and D2). A: Immunoblot analysis shows the efficiency of a dual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown on day 4 post-transfection. 1, Control siRNA; 2, cofilin-1 siRNA, D1 & ADF, and D1; 3, cofilin-1 siRNA, D2 & ADF, and D2. B and C: Cells grown for 4 days in Matrigel were fixed and labeled for F-actin (red) and an apical marker, protein kinase C (PKC) ζ (green). Representative microscopic images (B) and quantification of polarized cyst formation (C) are shown. Arrows show abnormal localization of the apical marker in ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cysts. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

ADF-Null Mice Are Characterized by Increased Mucosal Damage and Inflammation during Experimental Colitis

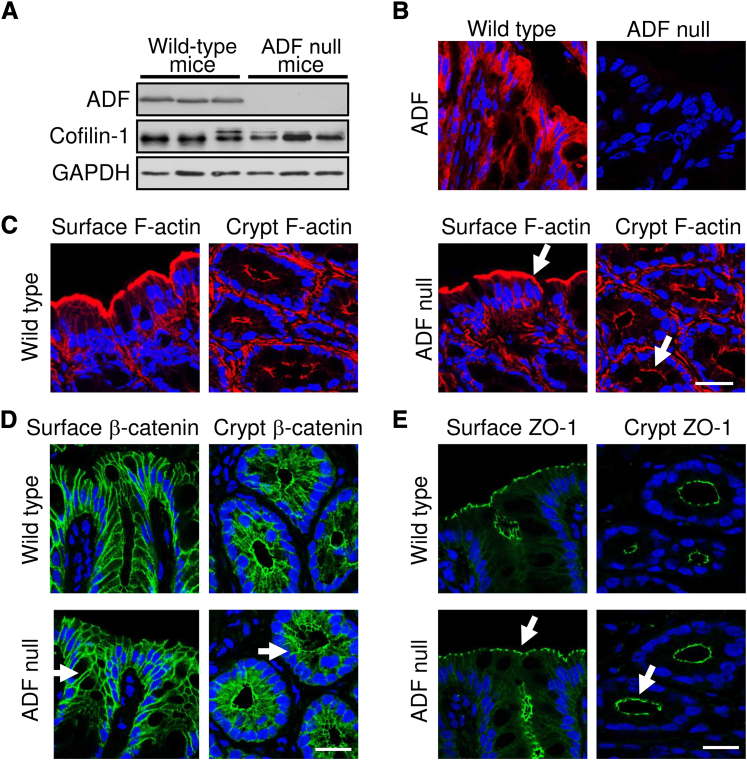

We next examined the role of ADF in the regulation of normal gut barrier and intestinal epithelial damage during mucosal inflammation in vivo. It has been shown that complete loss of cofilin-1 in mice is embryonically fatal due to defects in neural crest cell migration and neural tube closure.26 In contrast, a spontaneous Dstncorn1 mutation resulting in a total lack of ADF expression was identified in Corn1-mutant mice.57 Homozygous ADF-null animals are viable and fertile, and they do not demonstrate vivid phenotypic abnormalities, except for the development of a roughened opaque corneal surface.57 Therefore, Corn1-mutant mice represent an excellent model to study ADF functions in vivo.

Immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry analysis demonstrated complete loss of ADF protein expression and unaltered cofilin-1 level in the colonic epithelium of Corn1-mutant mice (Figure 6, A and B). ADF-null mice did not display any gastrointestinal symptoms, such as spontaneous body weight loss, diarrhea, or rectal bleeding (data not shown). Furthermore, F-actin organization (Figure 6C) and the morphology of AJs and TJs in the surface or crypt colonic epithelium (Figure 6, D and E) did not differ between ADF-null and wild-type animals. Finally, unchallenged ADF-null mice did not demonstrate enhanced passage of fluoresceinated dextran from gut lumen into blood plasma, thereby indicating unaltered permeability of the intestinal barrier (Figure 7C).

Figure 6.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) neither disrupts the apical F-actin cytoskeleton nor affects adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) integrity in the intestinal epithelium in vivo. A: The expression levels of ADF and cofilin-1 were determined in the colonic epithelium of wild-type and ADF-deficient corn mutant mice. B: The colonic sections of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were immunolabeled for ADF (red). Nuclear counterstaining (blue) was used for visualizing the position of individual cells. C: F-actin (red) was visualized in the colonic surface and crypt epithelium of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice. D and E: Colonic surface and crypt sections of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were labeled for AJ and TJ markers, β-catenin, and zonula occludens protein (ZO)-1 (green). Arrows show normal F-actin organization and unaltered localization of AJ and TJ proteins in the colonic mucosa of ADF-deficient animals. Scale bar = 20 μm. GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

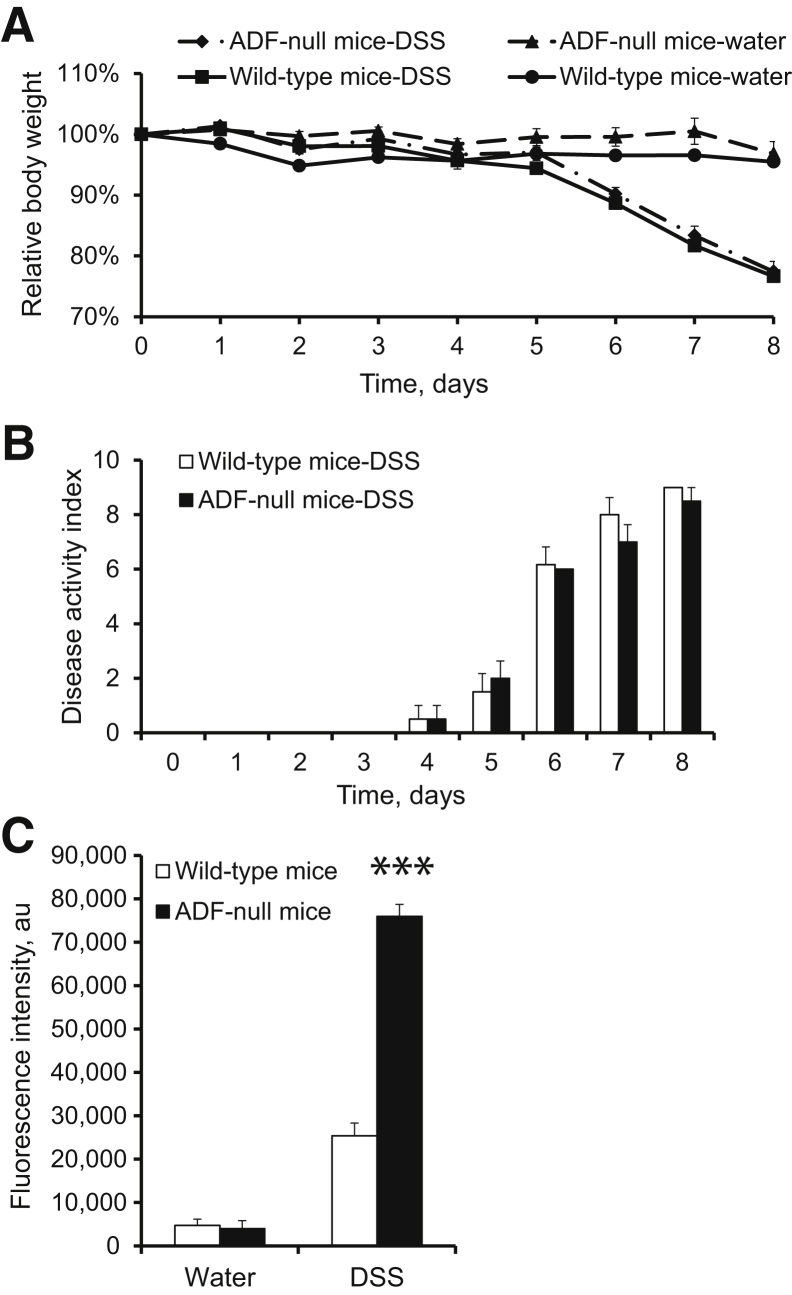

Figure 7.

Actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF)-null mice show exaggerated disruption of the intestinal mucosal barrier during experimental colitis. A and B: Experimental colitis was induced in wild-type and ADF-null mice by giving 5% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water. Loss of body weight (A) and disease activity index (B) were determined at different times during DSS administration. C: On day 8 of either DSS or water administration, intestinal permeability was examined by measuring transmucosal flux of fluoresceinated dextran. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 6. ∗∗∗P < 0.0005.

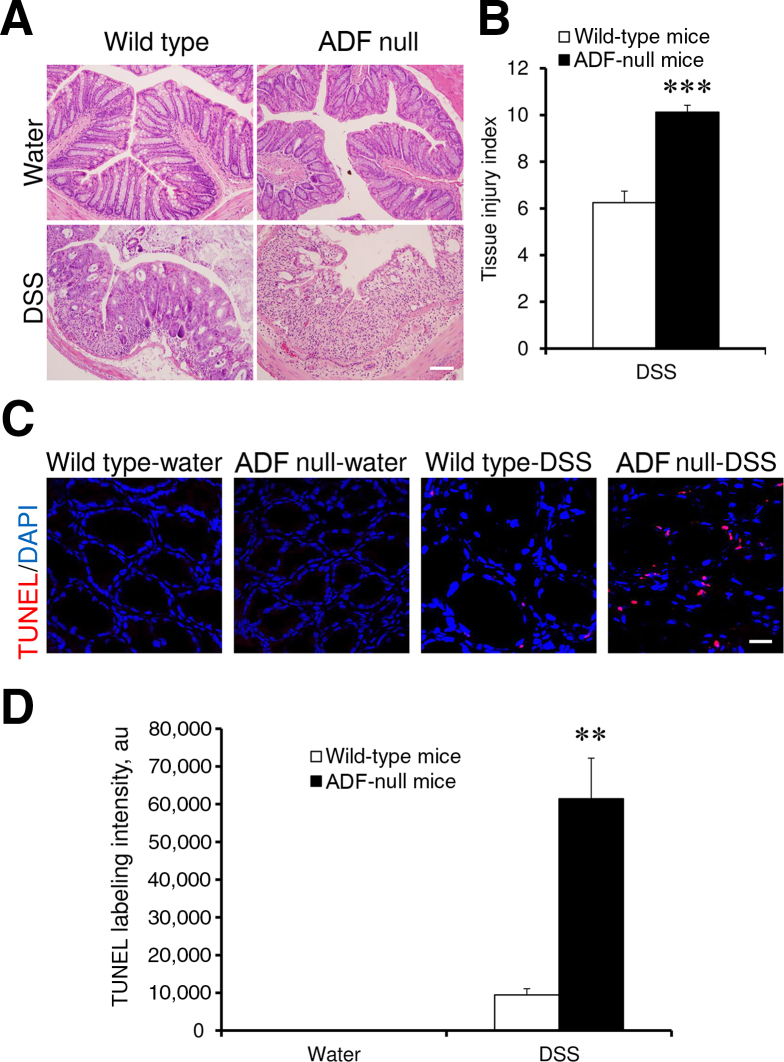

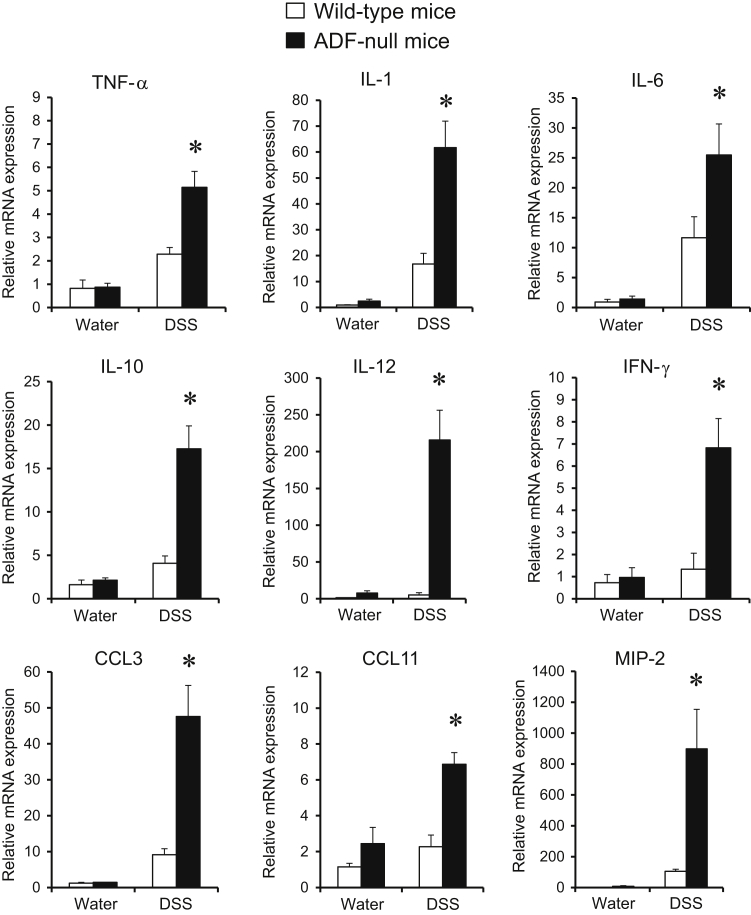

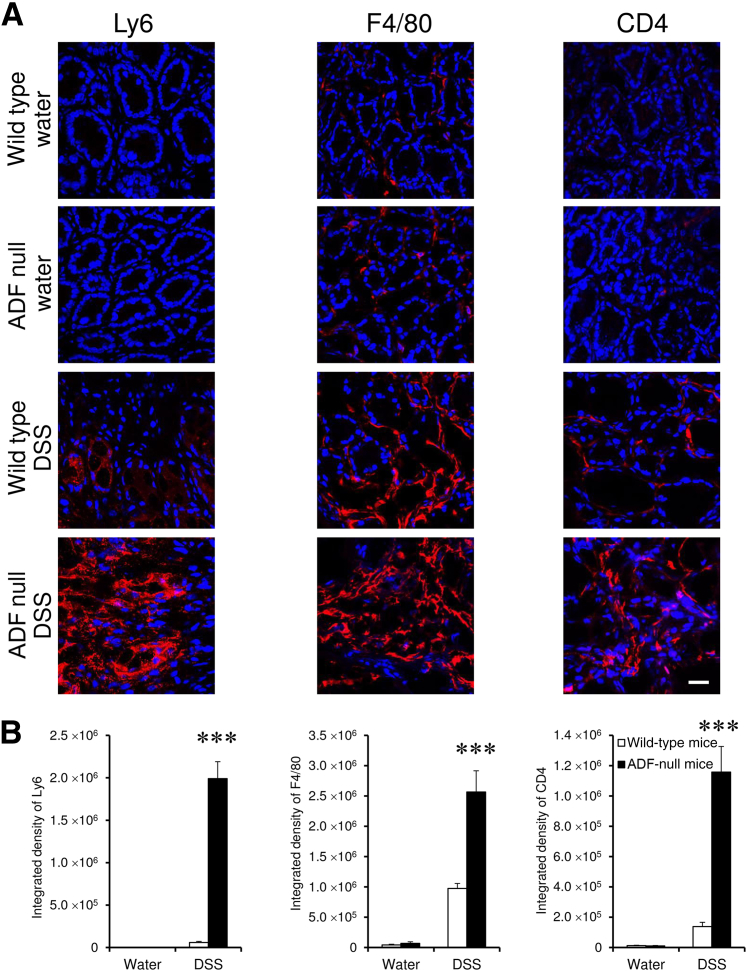

A DSS colitis model was used for comparing intestinal mucosal inflammation in ADF-null mice and their wild-type counterparts. These albino mouse strains appeared to be more resistant to colitis compared to strains from commonly used C57BL/6 mice. Thus, 1-week administration of 3% DSS did not cause significant body weight loss or other disease symptoms in either ADF-null or wild-type mice (data not shown). A higher DSS dose (5%) was required to induce colitis as manifested by decreased body weight, diarrhea, and intestinal bleeding. Interestingly, ADF-null and wild-type animals demonstrated similar severity of these disease symptoms (Figure 7, A and B). We next examined the effects of DSS administration on intestinal permeability. DSS dramatically increased transmucosal flux of fluorescent marker in all animals. Surprisingly, DSS-exposed ADF-deficient mice demonstrated a much more dramatic increase in intestinal permeability compared to wild-type animals (Figure 7C). Corroborating these permeability data, histological analysis demonstrated more severe tissue damage (Figure 8, A and B), increased cell apoptosis (Figure 8, C and D), and more pronounced AJ and TJ disassembly and cytoskeletal abnormalities (Supplemental Figure S6) in the colonic mucosa of DSS-treated ADF-null mice as compared to wild-type animals. To examine whether the observed increase in mucosal damage was related to a greater inflammatory response, we compared the expression of different proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as leukocyte infiltration in the colonic mucosa of healthy and DSS-treated animals. A quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis did not find changes in the mRNA expression profile for major proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the normal colonic mucosa of ADF-null animals as compared to wild-type controls (Figure 9). However, DSS administration triggered a much more dramatic expressional up-regulation of cytokine and chemokine expression in the colonic samples of ADF-null animals (Figure 9). Similarly, DSS-treated ADF-deficient mice were characterized by significantly greater mucosal infiltration of Ly6-positive neutrophils, F4/80-positive macrophages, and CD4-positive T cells (Figure 10). Together, these data indicate that loss of ADF exaggerates intestinal mucosal inflammation during DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 8.

Actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) deficiency increases epithelial damage and accelerates apoptosis in colonic mucosa during experimental colitis. Colonic samples of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were collected on day 8 of DSS or water administration. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used for evaluating epithelial integrity (A) and for calculating tissue injury index (B). C and D: Apoptotic cells were visualized using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (red). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 6. ∗∗P < 0.005, ∗∗∗P < 0.0005. Scale bars: 100 μm (A); 20 μm (C).

Figure 9.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) exaggerates cytokine expression in inflamed intestinal mucosa in vivo. Colonic samples of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were collected on day 8 of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) or water administration. The expression of different cytokines was determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Data are presented as means ± SEM. n = 6. ∗P < 0.05. CCL, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; IFN, interferon; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Figure 10.

Actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) deficiency increases leukocyte infiltration in the intestinal mucosa during experimental colitis. Colonic samples of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were collected on day 8 of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) or water administration. Neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells were visualized in the colonic mucosa using immunolabeling of their specific cellular markers: Ly6, F4/80, and CD4, respectively. The markers staining is red and the nuclear counterstaining is blue. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 6. ∗∗∗P < 0.0005. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Discussion

Members of the ADF and cofilin protein family are crucial regulators of actin dynamics that, under different cellular contexts, can promote either the assembly or disassembly of actin filaments.21, 58 These proteins are essential for key cellular functions such as cell division, motility, and survival.28, 29, 30, 31, 59 The present study demonstrates, for the first time, that cofilin-1 and ADF regulate the barrier function and assembly of intercellular junctions in intestinal epithelial cells. Our data suggest that ADF and cofilin-1 can act as unique or redundant regulators of epithelial junctions. For example, they are both essential for the establishment of the paracellular barrier and stimulated AJ and TJ reassembly (Figures 1 and 3 and Supplemental Figures S1 and S3). On the other hand, ADF and cofilin-1 play redundant roles in regulating AJ and TJ integrity in steady-state monolayers and the formation of 3D polarized cysts (Figures 2 and 5 and Supplemental Figures S2 and S5). Our data are consistent with those from previous reports describing the unique and overlapping functions of ADF and cofilin-1 in different cells and model organisms. For example, cofilin-1 has been shown to play unique roles in zebrafish gastrulation,41 mouse neural tube development,43, 26 and macrophage motility and antigen presentation.60 Furthermore, both ADF and cofilin-1 appear to be essential for the migration of breast cancer cells.30 Other studies have demonstrated redundant functions for ADF and cofilin-1 in mouse kidney morphogenesis,61 developing epidermis,62 and fibroblast cytokinesis.29 In some experimental systems, the unique functions of cofilin-1 can be explained by its preferential expression. Intestinal epithelial cells express both ADF and cofilin-1,26, 27 and our results strongly suggest functional specialization of these homologous proteins in the intestinal mucosa. Interestingly, loss of cofilin-1 results in defects in epithelial junctions that are more severe compared to those with ADF knockdown (Figure 1, Figure 3, and 4). Although these proteins have differences in their interactions with actin filaments, the molecular mechanisms that underlie the different activities of ADF and cofilin-1 in epithelial cells remain to be elucidated.

Our data suggest that the effects of ADF and cofilin-1 on epithelial junctions are mediated by the remodeling of the perijunctional F-actin cytoskeleton. Thus, the depletion of either protein attenuated the assembly of the perijunctional circumferential belt during calcium repletion and Lat B washout (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure S4). This result is consistent with the known roles of ADF and cofilin in promoting F-actin polymerization. Such polymerization-promoting activity is based on ADF- and cofilin-dependent severing of actin filaments, thus generating free barbed ends and subsequently increasing new filament nucleation.58 Interestingly, our recent study identified actin interacting protein 1 as a previously unanticipated regulator of apical junctions in model intestinal epithelium.44 Loss of actin interacting protein 1 increased paracellular permeability, attenuated AJ and TJ assembly, and impaired the establishment of apicobasal cell polarity.44 All of these effects were accompanied by defects in the organization of perijunctional F-actin bundles. Actin interacting protein 1 alone poorly affects actin filament dynamics, but it dramatically enhances cofilin-mediated filament severing and depolymerization.63 Hence, it is reasonable to suggest that actin interacting protein 1 controls junctional structure and dynamics by activating ADF and cofilin proteins. Together, our data emphasize the functional crosstalk between ADF or cofilin and actin interacting protein 1 as a novel mechanism that is essential for the integrity and function of the intestinal epithelial barrier.

ADF and cofilin-1 appear to play redundant roles in regulating the early stages of intestinal morphogenesis. Indeed, individual depletion of either ADF or cofilin-1 had little effect on the formation of epithelial cysts in 3D Matrigel; only dual knockdown of these proteins significantly impaired cystogenesis (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure S5). Consistent with these data, loss of ADF does not affect normal intestinal epithelial permeability or the structure of epithelial junctions in vivo (Figures 6 and 7C). Furthermore, ADF-deficient mice did not demonstrate significant clinical or biochemical signs of mucosal inflammation (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, and 10). Previous studies have reported the development of spontaneous inflammation in the corneas of ADF-null mice.64, 65 The disease manifested by an increased expression of Cxcl5 chemokine and leukocyte infiltration.64, 65 Limited corneal inflammation in ADF-null mice reflects the fact that ADF is highly expressed, while the cofilin-1 level is low in the corneal epithelium.57 In contrast, both proteins are abundant in the intestinal mucosa, where cofilin-1 can compensate for the loss of ADF expression. Despite this compensation, ADF-null mice develop epithelial damage and mucosal inflammation during DSS colitis that are more severe than those in wild-type animals (Figure 8, Figure 9, and 10 and Supplemental Figure S6), which highlights ADF as an important cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory protein in the intestinal mucosa. The molecular mechanisms of these mucosal-protective effects of ADF in vivo remain to be elucidated. It is unlikely that the loss of ADF would attenuate the direct toxicity of DSS in the intestinal epithelium. Indeed, the ADF and cofilin proteins are known positive regulators of cell apoptosis, which translocate into mitochondria causing cytochrome C release and caspase activation.59 Therefore, the decreased expression of these proteins should make epithelial cells more resistant to apoptosis. The most likely explanation for the exaggerated inflammatory response in ADF-null mice is the destabilization of the intestinal epithelial junctions, leading to more severe barrier disruption during DSS colitis (Figure 7 and Supplemental Figure S6). This disruption results in an increased exposure to luminal bacteria, thereby advancing mucosal inflammation. It is puzzling that the stronger inflammatory response and greater mucosal damage observed in ADF-null mice did not result in more severe macroscopic disease symptoms (Figure 7, A and B). This finding may reflect some yet-to-be-determined physiological and behavioral peculiarities of ADF-null mice (eg, food intake, microbiota composition, ion and water secretion) that limit the development of gastrointestinal diseases.

Rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton have been previously implicated in the dysfunctions of the intestinal epithelial barrier during mucosal inflammation.66, 67 However, these rearrangements result from enhanced cytoskeletal functions, such as an increase in actomyosin-dependent contractility. Our study indicates that the opposite events, such as defective F-actin turnover or decreased polymerization, can also weaken the epithelial barrier in inflamed intestinal mucosa. Because the cellular activities of ADF and cofilin are regulated by major protein kinases, phosphatases, phospholipids, and free radicals,19, 20, 58, 68 these proteins may act as key downstream molecular regulators that mediate the effects of different pathogens and external stressors on epithelial barriers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gianni Harris for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Judith M. Ball (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) for sharing HT-29 cl.F8 cells, and Dr. Sakae Ikeda (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI) for providing the initial breeding pairs of A.BY H2bc H2-t18f/SnJ mice.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants RO1 DK083968 and R01 DK084953 (A.I.I.) and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America grant 254881 (N.G.N.). The Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Massey Cancer Center is supported in part with funding from NIH-NCI core grant P30CA016059, and the VCU Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology Microscopy Facility is supported in part with funding from NIH-NINDS Center core grant 5P30NS047463.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.11.023.

Supplemental Data

Dual knockdown of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 results in an additive increase in epithelial permeability. HT-29 cells were transiently transfected with either control siRNA, individual ADF- and cofilin-1–specific siRNAs, or cotransfected with ADF and cofilin-1 siRNAs. A: Immunoblot analysis shows the efficiency of the single or dual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdowns on day 4 post-transfection. 1, Control siRNA; 2, Cofilin-1 siRNA, D1; 3, ADF siRNA, D1; 4, Cofilin-1 siRNA, D1 & ADF, D1. B: Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) analysis of ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers at different times post-transfection. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.005, ∗∗∗P < 0.0005. GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) or cofilin-1 does not affect junctional localization of β-catenin or claudin-4 in polarized epithelial cell monolayers. Control, ADF-depleted, or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were cultured for 7 days on semipermeable membrane filters. Cell were fixed, immunolabeled for the indicated AJ and TJ proteins, and examined by confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate intact β-catenin and claudin-4 labeling in ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Down-regulation of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 attenuates junctional reassembly during 24 hours of calcium repletion. Control, ADF-depleted, and cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were subjected to overnight calcium depletion to disassemble apical junctions, followed by calcium restoration for 24 hours to induce adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) reassembly. Arrows indicate AJ and TJ reassembly in control cells. Arrowheads indicate defects in junctional reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 impairs the reassembly of tight junctions (TJs) and reformation of the perijunctional F-actin belt in Latrunculin (Lat) B–treated epithelial cells. Polarized controls and ADF- or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cell monolayers were treated for 4 hours with 1 μmol/L Lat B to depolymerize actin filaments. The repolymerization of actin filaments was triggered by Lat B removal. Cells were fixed 1 hour after Lat B washout and were fluorescently labeled for TJs and F-actin. Arrows indicate complete reassembly of the perijunctional F-actin belt and zonula occludens protein (ZO) 1–based TJs in control cells. Arrowheads show the attenuation of actomyosin and TJ reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Selective knockdown of either actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) or cofilin-1 has little effect on the formation of intestinal epithelial cysts. Stable ADF or cofilin-1 knockdown in Caco-2 human colonic epithelial cells was performed using isoform-specific shRNAs. A: Immunoblot analysis shows the efficiency and specificity of individual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown. 1, Control shRNA; 2, Cofilin-1 shRNA; 3, ADF shRNA. B and C: Cells grown in Matrigel for 4 days were fixed and labeled for F-actin (red) and an apical marker, protein kinase C (PKC) ζ (green). Representative microscopic images (B) and the quantification of polarized cyst formation (C) are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) deficiency increases junctional disassembly and accelerates cytoskeletal alterations in colonic mucosa during experimental colitis. Colonic samples of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were collected on day 8 of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) administration. Adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) integrity and organization of the actin cytoskeleton were examined by fluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy. Arrowheads show more pronounced damage of AJs, TJs, and apical F-actin in ADF-null mice. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.

References

- 1.Hirokawa N., Tilney L.G. Interactions between actin filaments and between actin filaments and membranes in quick-frozen and deeply etched hair cells of the chick ear. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:249–261. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.1.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madara J.L. Intestinal absorptive cell tight junctions are linked to cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:C171–C175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.1.C171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanov A.I. Actin motors that drive formation and disassembly of epithelial apical junctions. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6662–6681. doi: 10.2741/3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodgers L.S., Fanning A.S. Regulation of epithelial permeability by the actin cytoskeleton. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:653–660. doi: 10.1002/cm.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivanov A.I., Naydenov N.G. Dynamics and regulation of epithelial adherens junctions: recent discoveries and controversies. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2013;303:27–99. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407697-6.00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng W., Takeichi M. Adherens junction: molecular architecture and regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002899. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeichi M. Dynamic contacts: rearranging adherens junctions to drive epithelial remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:397–410. doi: 10.1038/nrm3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson J.M., Van Itallie C.M. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002584. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuse M. Molecular basis of the core structure of tight junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a002907. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Z., Ding L., Lu Q., Chen Y.H. Claudins in intestines: distribution and functional significance in health and diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1:e24978. doi: 10.4161/tisb.24978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong S., Troyanovsky R.B., Troyanovsky S.M. Binding to F-actin guides cadherin cluster assembly, stability, and movement. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:131–143. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanov A.I., Parkos C.A., Nusrat A. Cytoskeletal regulation of epithelial barrier function during inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:512–524. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mege R.M., Gavard J., Lambert M. Regulation of cell-cell junctions by the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chhabra E.S., Higgs H.N. The many faces of actin: matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard T.D., Blanchoin L., Mullins R.D. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:545–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stossel T.P., Fenteany G., Hartwig J.H. Cell surface actin remodeling. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3261–3264. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brieher W.M., Yap A.S. Cadherin junctions and their cytoskeleton(s) Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Ponce A., Citalan-Madrid A.F., Velazquez-Avila M., Vargas-Robles H., Schnoor M. The role of actin-binding proteins in the control of endothelial barrier integrity. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:20–36. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bamburg J.R. Proteins of the ADF/cofilin family: essential regulators of actin dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:185–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ono S. Mechanism of depolymerization and severing of actin filaments and its significance in cytoskeletal dynamics. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;258:1–82. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)58001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein B.W., Bamburg J.R. ADF/cofilin: a functional node in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poukkula M., Kremneva E., Serlachius M., Lappalainen P. Actin-depolymerizing factor homology domain: a conserved fold performing diverse roles in cytoskeletal dynamics. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:471–490. doi: 10.1002/cm.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichetovkin I., Grant W., Condeelis J. Cofilin produces newly polymerized actin filaments that are preferred for dendritic nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Curr Biol. 2002;12:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrianantoandro E., Pollard T.D. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol Cell. 2006;24:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiggan O., Shaw A.E., DeLuca J.G., Bamburg J.R. ADF/cofilin regulates actomyosin assembly through competitive inhibition of myosin II binding to F-actin. Dev Cell. 2012;22:530–543. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurniak C.B., Perlas E., Witke W. The actin depolymerizing factor n-cofilin is essential for neural tube morphogenesis and neural crest cell migration. Dev Biol. 2005;278:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vartiainen M.K., Mustonen T., Mattila P.K., Ojala P.J., Thesleff I., Partanen J., Lappalainen P. The three mouse actin-depolymerizing factor/cofilins evolved to fulfill cell-type-specific requirements for actin dynamics. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:183–194. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravo-Cordero J.J., Magalhaes M.A., Eddy R.J., Hodgson L., Condeelis J. Functions of cofilin in cell locomotion and invasion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:405–415. doi: 10.1038/nrm3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotulainen P., Paunola E., Vartiainen M.K., Lappalainen P. Actin-depolymerizing factor and cofilin-1 play overlapping roles in promoting rapid F-actin depolymerization in mammalian nonmuscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:649–664. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tahtamouni L.H., Shaw A.E., Hasan M.H., Yasin S.R., Bamburg J.R. Non-overlapping activities of ADF and cofilin-1 during the migration of metastatic breast tumor cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2013;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Blume J., Duran J.M., Forlanelli E., Alleaume A.M., Egorov M., Polishchuk R., Molina H., Malhotra V. Actin remodeling by ADF/cofilin is required for cargo sorting at the trans-Golgi network. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1055–1069. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng Y., Liu Z., Wang S., Wang C., Qi S., Zhao J., Tian R., Su G. Effect of Robo4 on retinal endothelial permeability. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38:128–136. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.738844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov A.I., Hunt D., Utech M., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A. Differential roles for actin polymerization and a myosin II motor in assembly of the epithelial apical junctional complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2636–2650. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lui W.Y., Lee W.M., Cheng C.Y. Sertoli-germ cell adherens junction dynamics in the testis are regulated by RhoB GTPase via the ROCK/LIMK signaling pathway. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:2189–2206. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.011379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagumo Y., Han J., Arimoto M., Isoda H., Tanaka T. Capsaicin induces cofilin dephosphorylation in human intestinal cells: the triggering role of cofilin in tight-junction signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pepini T., Gorbunova E.E., Gavrilovskaya I.N., Mackow J.E., Mackow E.R. Andes virus regulation of cellular microRNAs contributes to hantavirus-induced endothelial cell permeability. J Virol. 2010;84:11929–11936. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01658-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashworth S.L., Sandoval R.M., Hosford M., Bamburg J.R., Molitoris B.A. Ischemic injury induces ADF relocalization to the apical domain of rat proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F886–F894. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.5.F886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thuijls G., de Haan J.J., Derikx J.P., Daissormont I., Hadfoune M., Heineman E., Buurman W.A. Intestinal cytoskeleton degradation precedes tight junction loss following hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2009;31:164–169. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31817fc310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu D., Pan H., Wan P., Wu J., Luo J., Zhu H., Chen J. AIP1 acts with cofilin to control actin dynamics during epithelial morphogenesis. Development. 2012;139:3561–3571. doi: 10.1242/dev.079491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pham H., Yu H., Laski F.A. Cofilin/ADF is required for retinal elongation and morphogenesis of the Drosophila rhabdomere. Dev Biol. 2008;318:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin C.W., Yen S.T., Chang H.T., Chen S.J., Lai S.L., Liu Y.C., Chan T.H., Liao W.L., Lee S.J. Loss of cofilin 1 disturbs actin dynamics, adhesion between enveloping and deep cell layers and cell movements during gastrulation in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X., Macara I.G. Par-3 mediates the inhibition of LIM kinase 2 to regulate cofilin phosphorylation and tight junction assembly. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:671–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grego-Bessa J., Hildebrand J., Anderson K.V. Morphogenesis of the mouse neural plate depends on distinct roles of cofilin 1 in apical and basal epithelial domains. Development. 2015;142:1305–1314. doi: 10.1242/dev.115493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lechuga S., Baranwal S., Ivanov A.I. Actin-interacting protein 1 controls assembly and permeability of intestinal epithelial apical junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G745–G756. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00446.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baranwal S., Naydenov N.G., Harris G., Dugina V., Morgan K.G., Chaponnier C., Ivanov A.I. Nonredundant roles of cytoplasmic beta- and gamma-actin isoforms in regulation of epithelial apical junctions. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:3542–3553. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-02-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naydenov N.G., Ivanov A.I. Adducins regulate remodeling of apical junctions in human epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3506–3517. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laukoetter M.G., Nava P., Lee W.Y., Severson E.A., Capaldo C.T., Babbin B.A., Williams I.R., Koval M., Peatman E., Campbell J.A., Dermody T.S., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A. JAM-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3067–3076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meehan T.F., Witherden D.A., Kim C.H., Sendaydiego K., Ye I., Garijo O., Komori H.K., Kumanogoh A., Kikutani H., Eckmann L., Havran W.L. Protection against colitis by CD100-dependent modulation of intraepithelial gammadelta T lymphocyte function. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:134–142. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cramer L.P., Briggs L.J., Dawe H.R. Use of fluorescently labelled deoxyribonuclease I to spatially measure G-actin levels in migrating and non-migrating cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2002;51:27–38. doi: 10.1002/cm.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivanov A.I., Pero R.S., Scheck A.C., Romanovsky A.A. Prostaglandin E(2)-synthesizing enzymes in fever: differential transcriptional regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R1104–R1117. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00347.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ivanov A.I., Hopkins A.M., Brown G.T., Gerner-Smidt K., Babbin B.A., Parkos C.A., Nusrat A. Myosin II regulates the shape of three-dimensional intestinal epithelial cysts. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1803–1814. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell D.M., Ball J.M. Characterization of a spontaneously polarizing HT-29 cell line, HT-29/cl.f8. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2004;40:297–302. doi: 10.1290/04100061.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonzalez-Mariscal L., Chavez de Ramirez B., Cereijido M. Tight junction formation in cultured epithelial cells (MDCK) J Membr Biol. 1985;86:113–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01870778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naydenov N.G., Hopkins A.M., Ivanov A.I. c-Jun N-terminal kinase mediates disassembly of apical junctions in model intestinal epithelia. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2110–2121. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morton W.M., Ayscough K.R., McLaughlin P.J. Latrunculin alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent polymerization. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:376–378. doi: 10.1038/35014075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang V.W., Brieher W.M. FSGS3/CD2AP is a barbed-end capping protein that stabilizes actin and strengthens adherens junctions. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:815–833. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ikeda S., Cunningham L.A., Boggess D., Hawes N., Hobson C.D., Sundberg J.P., Naggert J.K., Smith R.S., Nishina P.M. Aberrant actin cytoskeleton leads to accelerated proliferation of corneal epithelial cells in mice deficient for destrin (actin depolymerizing factor) Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1029–1037. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Troys M., Huyck L., Leyman S., Dhaese S., Vandekerkhove J., Ampe C. Ins and outs of ADF/cofilin activity and regulation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:649–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rehklau K., Gurniak C.B., Conrad M., Friauf E., Ott M., Rust M.B. ADF/cofilin proteins translocate to mitochondria during apoptosis but are not generally required for cell death signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:958–967. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jonsson F., Gurniak C.B., Fleischer B., Kirfel G., Witke W. Immunological responses and actin dynamics in macrophages are controlled by N-cofilin but are independent from ADF. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuure S., Cebrian C., Machingo Q., Lu B.C., Chi X., Hyink D., D'Agati V., Gurniak C., Witke W., Costantini F. Actin depolymerizing factors cofilin1 and destrin are required for ureteric bud branching morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luxenburg C., Heller E., Pasolli H.A., Chai S., Nikolova M., Stokes N., Fuchs E. Wdr1-mediated cell shape dynamics and cortical tension are essential for epidermal planar cell polarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:592–604. doi: 10.1038/ncb3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nadkarni A.V., Brieher W.M. Aip1 destabilizes cofilin-saturated actin filaments by severing and accelerating monomer dissociation from ends. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2749–2757. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cursiefen C., Ikeda S., Nishina P.M., Smith R.S., Ikeda A., Jackson D., Mo J.S., Chen L., Dana M.R., Pytowski B., Kruse F.E., Streilein J.W. Spontaneous corneal hem- and lymphangiogenesis in mice with destrin-mutation depend on VEGFR3 signaling. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1367–1377. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verdoni A.M., Smith R.S., Ikeda A., Ikeda S. Defects in actin dynamics lead to an autoinflammatory condition through the upregulation of CXCL5. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al-Sadi R., Boivin M., Ma T. Mechanism of cytokine modulation of epithelial tight junction barrier. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:2765–2778. doi: 10.2741/3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cunningham K.E., Turner J.R. Myosin light chain kinase: pulling the strings of epithelial tight junction function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1258:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernard O. Lim kinases, regulators of actin dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dual knockdown of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 results in an additive increase in epithelial permeability. HT-29 cells were transiently transfected with either control siRNA, individual ADF- and cofilin-1–specific siRNAs, or cotransfected with ADF and cofilin-1 siRNAs. A: Immunoblot analysis shows the efficiency of the single or dual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdowns on day 4 post-transfection. 1, Control siRNA; 2, Cofilin-1 siRNA, D1; 3, ADF siRNA, D1; 4, Cofilin-1 siRNA, D1 & ADF, D1. B: Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) analysis of ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers at different times post-transfection. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗∗P < 0.005, ∗∗∗P < 0.0005. GADPH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) or cofilin-1 does not affect junctional localization of β-catenin or claudin-4 in polarized epithelial cell monolayers. Control, ADF-depleted, or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were cultured for 7 days on semipermeable membrane filters. Cell were fixed, immunolabeled for the indicated AJ and TJ proteins, and examined by confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate intact β-catenin and claudin-4 labeling in ADF- and cofilin-1–depleted cell monolayers. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Down-regulation of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 attenuates junctional reassembly during 24 hours of calcium repletion. Control, ADF-depleted, and cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cells were subjected to overnight calcium depletion to disassemble apical junctions, followed by calcium restoration for 24 hours to induce adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) reassembly. Arrows indicate AJ and TJ reassembly in control cells. Arrowheads indicate defects in junctional reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.

Loss of actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) and cofilin-1 impairs the reassembly of tight junctions (TJs) and reformation of the perijunctional F-actin belt in Latrunculin (Lat) B–treated epithelial cells. Polarized controls and ADF- or cofilin-1–depleted HT-29 cell monolayers were treated for 4 hours with 1 μmol/L Lat B to depolymerize actin filaments. The repolymerization of actin filaments was triggered by Lat B removal. Cells were fixed 1 hour after Lat B washout and were fluorescently labeled for TJs and F-actin. Arrows indicate complete reassembly of the perijunctional F-actin belt and zonula occludens protein (ZO) 1–based TJs in control cells. Arrowheads show the attenuation of actomyosin and TJ reassembly caused by either ADF or cofilin-1 depletion. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Selective knockdown of either actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) or cofilin-1 has little effect on the formation of intestinal epithelial cysts. Stable ADF or cofilin-1 knockdown in Caco-2 human colonic epithelial cells was performed using isoform-specific shRNAs. A: Immunoblot analysis shows the efficiency and specificity of individual ADF and cofilin-1 knockdown. 1, Control shRNA; 2, Cofilin-1 shRNA; 3, ADF shRNA. B and C: Cells grown in Matrigel for 4 days were fixed and labeled for F-actin (red) and an apical marker, protein kinase C (PKC) ζ (green). Representative microscopic images (B) and the quantification of polarized cyst formation (C) are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) deficiency increases junctional disassembly and accelerates cytoskeletal alterations in colonic mucosa during experimental colitis. Colonic samples of wild-type and ADF-deficient mice were collected on day 8 of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) administration. Adherens junction (AJ) and tight junction (TJ) integrity and organization of the actin cytoskeleton were examined by fluorescence labeling and confocal microscopy. Arrowheads show more pronounced damage of AJs, TJs, and apical F-actin in ADF-null mice. Scale bar = 20 μm. ZO, zonula occludens.