Abstract

Study design

Case series

Background and purpose

The literature has emphasized the use of exercise as an intervention for individuals with lumbopelvic pain. However, there is limited information to guide clinicians in exercise selection for those with sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction. Altered function of the gluteus maximus has been found in those with SI joint dysfunction. The objective of this case series was to assess the effectiveness of an exercise program directed at increasing gluteus maximus strength in those with clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction.

Case descriptions

The eight subjects in this series presented with lumbopelvic pain and clinical evidence of SI joint dysfunction. Each subject underwent 10 treatments over five weeks consisting of five exercises directed at strengthening the gluteus maximus. Radiological assessment and clinical examination were performed to rule out potential concurrent pathologies. Visual analog pain scale, the Oswestry Disability Index, and strength assessed via hand held dynamometry were measured pre- and post-intervention.

Outcomes

A significant (p<0.001) weakness in gluteus maximus was noted when comparing the uninvolved and involved sides pre-intervention. After completing the strengthening exercise program over 10 visits, statistically significant (p<0.002) increases in gluteus maximus strength and function were found, as well as a decrease in pain. All subjects were discharged from physical therapy and able to return to their normal daily activities.

Discussion

The results of this case series support the use of gluteus maximus strengthening exercises in those with persistent lumbopelvic pain and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction.

Keywords: Hip, low back pain, rehabilitation, sacroiliac joint

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Despite sacroiliac joint (SI) dysfunction being a well-documented clinical entity that can result in pain and loss of function,1 there is little research available to direct treatment interventions. This includes specific exercise selection. Previous authors have suggested that altered gluteus maximus muscle function can be associated with SI joint dysfunction.2-7 However, the effectiveness of an exercise program directed at increasing gluteus maximus strength in those with clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction has not been studied.

The SI joint provides the link for ground reaction forces between the lower extremities and trunk during weight-bearing activities.4 Proper activation of abdominal, leg, and back musculature allow for normal load transmission across the lumbopelvic region.8,9 Specifically, a relationship between the gluteus maximus and SI joint has been studied.2,3 Anatomical studies suggest the gluteus maximus can contribute to stabilizing the SI joint with muscle fibers being perpendicular to the joint surfaces.5,6 Additionally, activation of the gluteus maximus was found to increase compressive force across the SI joint.5,6 Clinical studies have shown individuals with SI joint dysfunction demonstrate abnormal gluteus maximus recruitment during weight bearing activities.4 Therefore it is hypothesized that weakness of the gluteus maximus can be related to abnormal loading of the SI joint and be a cause of the impairments associate with SI joint dysfunction.3

There is evidence to suggest that exercises directed at improving gluteus maximus function should be included as an intervention in those with SI joint dysfunction. The aim of this study was to report the outcome of eight subjects with lumbopelvic pain and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction who participated in an exercise program directed at increasing gluteus maximus strength. This work received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Santa Casa Hospital, São Paulo-SP, Brazil and all participants gave informed, written consent prior to participation.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The eight subjects were evaluated at baseline and after 10 treatment sessions. The mean age of the subjects was 33 years (range, 18-43 years), 4 females and 4 males, 6 were considered sedentary and 2 were active, with average pain duration of 13 months (range, 5-24 months). (Table 1) All subjects were recruited at Santa Casa Hospital. Evaluation consisted of an assessment of trunk and hip range of motion, visual analog scale [VAS] pain assessment10 and self-reported level of function using the Oswestry Disability Index.11,12 Gluteus maximus strength was measured with a hand-held dynamometer.13 Slump Test,14 Laseque straight-leg maneuver,15 Piriformis Test (buttock or sciatic pain during hip medial rotation), Grava Test (pain during hip adduction and abdominal contraction in a prone position),16 flexion-abduction and external rotation test (FABER),17 and the Scour Test,18 were performed to rule out concurrent sources of symptoms.

Table 1.

Results of pain and functional scales at baseline and re-evaluation.

| Subjects | Age (year) | Gender | Relevant History | Symptom duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | Female | Sedentary / Student | 5 months |

| 2 | 32 | Male | Recreational soccer player | 1 year |

| 3 | 27 | Male | Run 3 times per week | 1 year |

| 4 | 40 | Female | Sedentary / Teacher | 2 years |

| 5 | 38 | Female | Sedentary | 6 months |

| 6 | 41 | Female | Sedentary | 1 year |

| 7 | 43 | Male | Sedentary / Driver | 10 months |

| 8 | 26 | Male | Sedentary | 2 years |

Four clinical tests were used to assess for SI dysfunction, as described by McGrath et al.19 These tests included the SI compression, SI distraction, Squish, and Gaenslen.19 Subjects were considered to have SI dysfunction when at least three out of four of these tests were positive with pain provocation.19 The results of these tests are provided in Table 2. Only subjects with clinical evidence of SI dysfunction were included in the study. Moreover, all subjects included in this study had unilateral lumbopelvic pain in the SI region for at least 12 weeks (chronic) and had no previous physical therapy treatment. Subjects with clinical and imaging evidence of any spinal or pelvic co-morbidity potentially responsible for pain radiating through the sacroiliac region, signs of lower limb length discrepancy, or with cognitive deficiency were excluded.

Table 2.

Results of clinical tests.

| Tests | Subjects | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slump | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lasegue | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Piriformis | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Grava | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FABER | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Scour | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Compression | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Distraction | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| Squish | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gaenslen | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

Abbreviation: + (positive test), - (negative test); FABER = Flexion, abduction, external rotation test

It is important to highlight that none of the subjects had SI joint degeneration, as evaluated by anteroposterior pelvic X-rays.

Exercise Protocol for Gluteus Maximus Strength

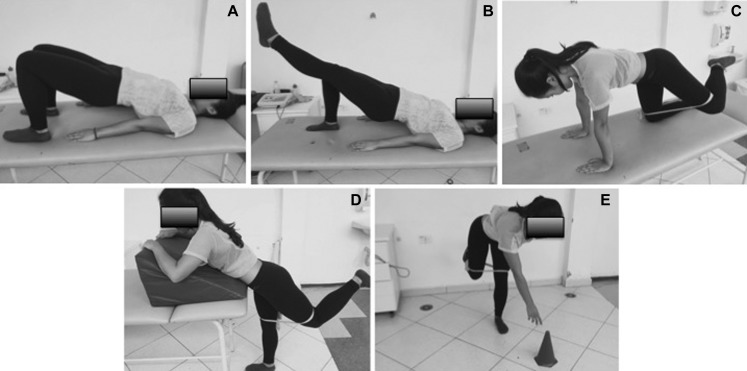

The subjects attended physical therapy two times per week for a total of 10 visits. Each visit lasted approximately 30 minutes. In the first five sessions, subjects performed the following exercises to strengthen the gluteus maximus: bilateral bridge, unilateral bridge, and non-weight-bearing hip extension in prone with the knee flexed at 90 degrees. In the next five sessions, abduction and external rotation in a quadruped (“fire hydrant” exercise) and weight-bearing hip extension (known as “deadlift” exercise) (Figure 1) were added. This exercise program was developed and based on previous electromyography studies.20,21 Each exercise was performed for 10 repetitions. Elastic resistance was added to the fire hydrant, hip extension in prone and deadlift exercises to allow each subject to perform at a 10-repetition maximum. The resistance for each subject was adjusted weekly as needed. The exercise program was performed under direct supervision only during the physical therapy sessions.

Figure 1.

Exercises of the gluteus maximus strengthening program. A) Bilateral bridge, B) Unilateral bridge, C) Hip abduction in quadruped, D) Hip extension in prone (with knee flexed), E) Dead lift.

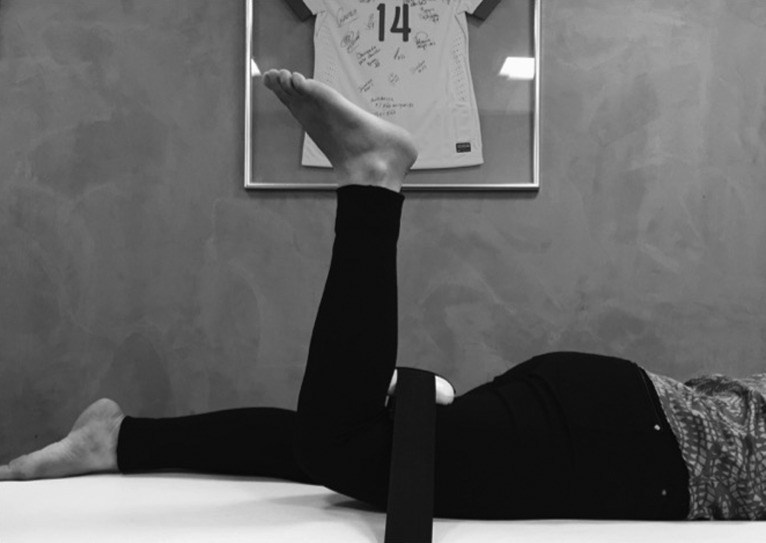

Measuring Muscle Strength

The strength of the gluteus maximus was evaluated by measuring the maximum isometric voluntary contraction using a hand-held dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Co, Lafayette, IN). Strength testing was performed with the subject in a prone position, the knee flexed to 90 degrees, and hip in slight lateral rotation. The dynamometer was positioned on the distal third of the posterior aspect of the femur and stabilized with an inelastic band secured to the treatment table prevent lower extremity movement (Figure 2). During strength testing, two submaximal trials were used to familiarize the subjects with the testing procedure.22,23 This was followed by three trials of maximum isometric effort. For data analysis, the average value of the three trials of maximum effort was used. A pilot study was performed to assess reliability of this strength assessment. Eight healthy volunteers (four men and four women) were tested according to the protocol described above. The results of measuring muscle strength indicated good reliability, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs 2,1) of 0.86.11,16

Figure 2.

Position for gluteus maximus strength assessment.

A comparison between the pre- and post-intervention was performed using the paired t-test with p values set at 0.05. The software Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 19.0 was used for these analyses.

OUTCOMES

The results of the strength assessments are provided in Table 3. Significant (p<0.001) gluteus maximus weakness was noted when comparing the uninvolved to involved sides. After completing the 5-week exercise program, a significant (p = 0.002) increase in gluteus maximus strength on the involved side was found, ranging from 17%-29% (Table 3). No changes were observed on the uninvolved side in the pre- versus post-treatment analyses. Additionally, a significant (p<0.001) decrease in pain as noted on the VAS and a significant (p<0.001) increase self-reported function as noted with by the Oswestry (Table 4) were also identified when comparing pre- and post-intervention values. All subjects were discharged from physical therapy and able to return to their normal daily activities.

Table 3.

Strength of gluteus maximus muscle in the involved and uninvolved side at baseline and re-evaluation (5-week post-treatment evaluation).

| Baseline (kg)* | Re-evaluation (kg) | Change (%)** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Uninvolved | Involved | Involved | Involved |

| 1 | 19.6 | 15.5 | 19.2 | 23.9 |

| 2 | 24.8 | 20.2 | 24.9 | 23.3 |

| 3 | 22.9 | 19.7 | 24.6 | 24.9 |

| 4 | 14.7 | 12.1 | 15.4 | 27.3 |

| 5 | 16.9 | 13.9 | 17.3 | 24.5 |

| 6 | 15.4 | 13.1 | 17.0 | 29.8 |

| 7 | 23.9 | 20.5 | 25.1 | 22.4 |

| 8 | 26.3 | 22.3 | 26.1 | 17.0 |

Statistically different between groups (p<.001)

Statistically different post-treatment in the involved side (p = .002)

Table 4.

Results of pain and functional scales at baseline and re-evaluation.

| Subjects | VAS* | Oswestry* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 80 | 14 |

| 2 | 9 | 1 | 82 | 28 |

| 3 | 8 | 2 | 76 | 16 |

| 4 | 10 | 0 | 96 | 0 |

| 5 | 8 | 3 | 78 | 32 |

| 6 | 8 | 2 | 72 | 26 |

| 7 | 7 | 0 | 84 | 0 |

| 8 | 10 | 1 | 90 | 16 |

VAS = Visual analogue scale, 0-10 cm where 0 means “no pain”and 10 means “worst imaginable pain during last week”, Oswestry (0-100 points, higher score represents more incapacity

Statistically different between groups for the VAS and Oswestry (p<.001)

DISCUSSION

The results of this case-series indicate that subjects with persistent pain in the lumbopelvic region and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction demonstrated gluteus maximus weakness when comparing the involved and uninvolved sides. Following a five-week strengthening program directed at the gluteus maximus, subjects demonstrated a significant increase in function, decrease in pain, and increase in strength. These results support the inclusion of gluteus maximus strengthening exercises in those with persistent pain in the lumbopelvic region and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction.

An exercise program is commonly included for those with SI pain. The rationale for strengthening exercises has included stabilization of the SI joint through dynamic muscle activity.24 The joint surfaces of the SI joint are flat and oriented in a vertical plane. While this alignment may be ideal for load transfer, the SI joint may be vulnerable to injury provoked by vertical shear forces.4 Additionally, the viscoelastic properties of the ligaments surrounding the SI joint may show a tendency to creep under prolonged loading. These studies suggest that the musculature and fascia of the lumbopelvic complex are required to stabilize the SI joint.2,5-7 Anatomical and biomechanical studies have supported the hypothesis that the gluteus maximus may generate compressive forces at the SI joint and assist in load transfer between the lower limb and trunk.2,5-7 While it is controversial whether SI joint symptoms are a results of SI joint instability, the results of the current case series support the inclusion of gluteus maximus strengthening exercises to improve patient outcomes in those with SI joint dysfunction. While it is unknown if these exercises actually functionally stabilized the SI joint, subjects in this study had a significant decrease in pain and improvement in function.

Previous research has shown that exercises are effective in altering pain and functional disability in subject with segmental lumbar instability and altered motor recruitment patterns.25 It has been hypothesized that delayed onset of the gluteus maximus may alter the compressive force on the SI joint and hinder mechanisms required for load transfer. Delayed onset of the gluteus maximus contraction has been identified in those with SI joint pain.4 Therefore it would seem appropriate that exercises should be directed at improving the gluteus maximus timing and function. While it is not known whether the gluteus maximus activation patterns were normalized, the subjects demonstrated an increase in strength and improved function.

In the treatment of those with low back pain, evidence supports the use of the joint mobilization and exercise.26 Identifying SI dysfunction can be difficult in subjects with low back pain. Furthermore, diagnosing the exact cause of SI joint pain is controversial. However, research suggests that SI dysfunction is present when three out of four tests (SI compression, SI distraction, squish, and Gaenslen) were positive.19 The results of the current case-series suggest that in those with lumbopelvic pain and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction, exercise directed at strengthening the gluteus maximus should be included in the overall exercise program. When analyzing the strength assessment data of the subjects considered “active” (patients 2 and 3), there were no significant differences when compared to the sedentary subjects (others), which indicates a possible beneficial effect for both populations.

One of the limitations of this study was the small sample size, as is typical with case series research. However, even with only eight subjects significant differences in strength, VAS, and function were found. Considering the minimal clinically important differences (MCID) used to measure pain and function,27 all subjects presented clinically significant changes (Table 4): at least a reduction of two points on VAS scale,27 and a difference of six points on the Oswestry Disability Index questionnaire.28,29 Further research is needed using a longer follow-up period, larger sample size and include a multi-modal intervention program with mobilization and a comprehensive exercise program that includes gluteus maximus strengthening.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this case series of eight subjects with clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction with gluteus maximus weakness demonstrated improvements in function, pain, and strength after completing a strengthening program. These results support the inclusion of gluteus maximus strengthening exercises in those with persistent lumbopelvic pain and clinical tests positive for SI joint dysfunction. Further research is needed to determine the short- and long-term effectiveness of this approach in the overall management of subjects with SI dysfunction.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lingutla KK Pollock R Ahuja S. Sacroiliac joint fusion for low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(6):1924-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker PJ Hapuarachchi KS Ross JA Sambaiew E Ranger TA Briggs CA. Anatomy and biomechanics of gluteus maximus and the thoracolumbar fascia at the sacroiliac joint. Clin Anat. 2014; 27:234-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hossain M Nokes LD. A model of dynamic sacro-iliac joint instability from malrecruitment of gluteus maximus and biceps femoris muscles resulting in low back pain. Med Hypotheses. 2005; 65:278-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hungerford B Gilleard W Hodges P. Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 2003; 28:1593-1600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snijders CJ Vleeming A Stoeckart R. Transfer of lumbosacral load to iliac bones and legs Part 1: Biomechanics of self-bracing of the sacroiliac joints and its significance for treatment and exercise. Clin Biomech. 1993; 8:285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Wingerden JP Vleeming A Buyruk HM Raissadat K. Stabilization of the sacroiliac joint in vivo: verification of muscular contribution to force closure of the pelvis. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(3):199-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vleeming A Pool-Goudzwaard AL Stoeckart R van Wingerden JP Snijders CJ. The posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Its function in load transfer from spine to legs. Spine. 1995;20:753-758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leinonen V Kankaanpaa M Airaksinen O Hanninen O. Back and hip extensor activities during trunk flexion/extension: effects of low back pain and rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson CA Snijders CJ Hides JA Damen L Pas MS Storm J. The relation between the transversus abdominis muscles, sacroiliac joint mechanics, and low back pain. Spine. 2002;27:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LOP Maher CG Latimer J Ferreira PH Ferreira ML Pozzi G.C Freitas LMA. Clinimetric testing of three self-report outcome measures for low back pain patients in Brazil, witch one is the best? Spine. 2008;33(22):2459-2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guimarães RP Alves DPL Silva GB Bittar ST Ono NK Honda E Polesello GC Junior WR Carvalho NA. Tradução e adaptação transcultural do instrumento de avaliação do quadril Harris Hip Score. Acta Ortop Bras. 2010; 18(3):142-147. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigatto R Alexandre NM Correa Filho HRF. Development of a Brazilian Portuguese version of the Oswestry Disability Index: cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity. Spine. 2007;32(4):481-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandinelli S Benvenuti E Del Lungo I Baccini M Benvenuti F Di Iorio A Ferrucci L. Measuring muscular strength of the lower limbs by hand-held dynamometer: a standard protocol. Aging. 1999;11(5):287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiman MP Loudon JK Goode AP. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for assessment of hamstring injury: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(4):223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazbek PM Ovanessian V Martin RL Fukuda TY. Nonsurgical treatment of acetabular labrum tears: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(5): 346-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen M Abdalla R. Sports Injuries: Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Revinter; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philippon M Schenker M Briggs K Kuppersmith D. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007; 15(7): 908-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magee D. Musculoskeletal Assessment. São Paulo, Brazil: Manole; 2005, 4 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath MC. Composite sacroiliac joint pain provocation tests: A question of clinical significance. Int J Osteop Med. 2010;13: 24-30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Distefano LJ Blackburn JT Marshall SW Padua DA. Gluteal muscle activation during common therapeutic exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(7):532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekstrom RA Donatelli RA Carp KC. Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(12):754-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolgla LA Malone TR Umberger BR Uhl TL. Hip strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(1):12-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wikholm JB Bohannon RW. Hand-held Dynamometer Measurements: Tester Strength Makes a Difference. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1991; 13(4):191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mooney V Pozos R Vleeming A Gulick J Swenski D. Exercise treatment for sacroiliac pain. Orthopedics. 2001;24(1):29-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Javadian Y Behash H Akbari M Tagipour-Darzi M, Zekavat H > The effects of stabilization exercises on pain and disability of patients with lumbar segemental instability. J Back Musc Rehabil. 2012;25:124-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delitto A George SZ Van Dillen LR Whitman JM Sowa G Shekelle P. Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Associaton. Low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(4):A1-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balague F Mannion AF Pellise F Cedraschi C. Clinical update: low back pain. Lancet. 2007;369(9563);726-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achten J Parsons NR Edlin RP Griffin DR Costa ML. A randomised controlled trial of total hip arthroplasty versus resurfacing arthroplasty in the treatment of young patients with arthritis of the hip joint. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritz JM Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81(2):776-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]