Abstract

We describe a novel method for mutant allele quantitation using allele-specific PCR. The method uses a heterozygous plasmid containing one wild-type and one mutant sequence as a calibrator that is run at a single concentration, with each quantitative allele-specific PCR run. PCR data from both calibrator alleles, together with predetermined PCR efficiencies, are used to quantitate the mutant allele burden in unknown specimens. We demonstrate the utility of this method by using it to calculate BRAF V600E allele frequencies in cases of hairy-cell leukemia and show that it generates data that are comparable to those obtained via allele quantitation using conventional standard curves over a wide range of allelic ratios. This method is not subject to errors that may be introduced in traditional standard curves as the result of variations in pippetting or errors in the calculation of the absolute copy numbers of standards. Furthermore, it simplifies the workflow in the clinical laboratory and would provide significant advantages for efforts to standardize clinical quantitative PCR testing.

Activating oncogenic mutations occur in many genes and often cluster in a few affected codons. In several tumor types, a few recurrent mutations occur. These often affect important regulatory or enzymatic components of the resulting protein and, thus, are seen across the spectrum of patients. In these scenarios, alternatives to classic DNA sequence analysis are quicker, cheaper, and more sensitive for routine testing in the clinical laboratory. Allele-specific PCR is the most sensitive of these methods and is particularly useful in cases of a predominant recurrent base change.1 Several different amplification detection chemistries are available for allele-specific PCR, all with various potential benefits and drawbacks. Through the use of hydrolysis probe-based detection, allele-specific PCR has the added advantage of yielding quantitative data and is, thus, useful for ongoing patient monitoring, potentially providing insights into the kinetics of treatment response through serial testing. Furthermore, quantitative assessment of mutant allele frequency can provide additional important clinical information. It can be of prognostic2 and/or diagnostic3 value, as in the case of the JAK2 V617F mutation, and it can also reveal tumor heterogeneity.4 This technique usually requires the generation of standard curves that, in turn, rely on accurate DNA quantitation to calculate the absolute copy number of DNA molecules in a sample.

The BRAF protein kinase acts in the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway,5 and activating mutations at residue V600 have been described in several neoplasms, including colorectal, lung, and thyroid cancers.6, 7, 8 Determining the BRAF mutation status in these cancers is of prognostic value9, 10, 11 and aids in treatment decisions, especially in light of the availability of selective BRAF inhibitors.5, 7, 12 Recently, the BRAF V600E mutation was found to be associated with nearly all cases of classic hairy-cell leukemia (HCL)13, 14 and could serve as a specific diagnostic marker apart from traditional morphological and flow cytometric analysis. Thus far, analyses have indicated that the V600E substitution mutation, a change that results in high constitutive kinase activity, represents most BRAF-activating mutations that occur in the setting of human malignancies.15

BRAF mutations have been detected by direct sequencing,16 high-resolution melting,17, 18 and, in the case of theV600E mutation, allele-specific PCR.19, 20, 21, 22 Herein, we describe a modification of quantitative allele-specific PCR testing for BRAF V600E, suitable for detection of the mutation in blood and bone marrow samples or in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue. Notably, this test uses a heterozygous plasmid calibrator harboring both a wild-type (WT) and a V600E mutant allele and allows accurate quantification of the mutant allele burden without the need for a standard curve. Furthermore, we believe that this general strategy is suitable for accurate quantitation of any recurrent substitution mutation.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples, Flow Cytometry, Cell Lines, and DNA Extraction

Excess cryopreserved peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirate–derived white blood cells were obtained from the ARUP hematological flow cytometry laboratory, and FFPE tissue samples from melanoma, colon cancer, and thyroid cancer were selected from the archives of ARUP Laboratories, with the approval of the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (No. 7275; Salt Lake City, UT). Flow cytometric immunophenotyping was performed as previously described.23 All HCL samples were reviewed by a hematopathologist (D.W.B or T.W.K) and were diagnostic of HCL. Solid tumor specimens were also confirmed by a pathologist. The BRAF V600E homozygous cell line SK-MEL-28 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was grown in minimal essential medium (Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA). Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes with the Puregene kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). For solid tumor specimens, the tumor area was identified on H&E-stained slides and then manually microdissected from corresponding aniline blue–stained slides. The tissue was subsequently treated with 200 μg of proteinase K in 200 μL of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.5% Tween 20, overnight at 65°C, and then boiled for 10 minutes and centrifuged.

Plasmid Construction

For the generation of the heterozygous plasmid calibrator, pBRAF-HET, a BRAF WT fragment was PCR amplified with the following primers: BRAFpst, 5′-GTCCTGCAGATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGG-3′ (forward); and BRAFeco, 5′-GTCGAATTCGTAACTCAGCAGCATCTCAGGG-3′ (reverse), from normal genomic DNA. In addition, a BRAF V600E mutant fragment was PCR amplified with the following primers: BRAFeco, 5′-GTCGAATTCATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGG-3′ (forward); and BRAFhin, 5′-GTCAAGCTTGTAACTCAGCAGCATCTCAGGG-3′ (reverse), from genomic DNA of the cell line SK-MEL-28. PCRs were performed using Phusion HF polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The WT PCR fragment was digested with the restriction endonucleases, PstI and EcoRI (all restriction endonucleases were from New England Biolabs and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions), and the mutant PCR fragment was digested with the restriction endonucleases, EcoRI and HindIII. The plasmid vector, pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), was digested with the restriction endonucleases, PstI and HindIII, treated with calf intestinal phosphatase, and gel purified. The linearized plasmid and both WT and mutant fragments were combined and ligated using T4 DNA ligase. For quantitative PCR, the pBRAF-HET plasmid was linearized with the restriction endonuclease, EcoRI.

For the generation of single-allele WT or V600E mutant plasmids, pBRAF-WT and pBRAF-MUT, the respective alleles were amplified from normal and SK-MEL-28 genomic DNA with the following primers: BRAFnot, 5′-GTCGCGGCCGCATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGG-3′ (forward); and BRAFasc, 5′-GTCGGCGCGCCGTAACTCAGCAGCATCTCAGGG-3′ (reverse). Both the WT and mutant PCR fragments were digested with the restriction endonucleases, NotI and AscI, and cloned into NotI and AscI-digested pENTR (Invitrogen Corp), as previously described. The correct configuration and sequence of each plasmid were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

For the generation of WT and mutant standard curves, the single-allele plasmids were digested with the restriction endonuclease, NotI (New England Biolabs), and then quantitated with the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Invitrogen Corp) on the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen Corp). All plasmids were diluted in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.05% Tween 20.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Sequences for allele-specific WT and mutant forward primers (forward WT, 5′-TAGGTGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACCGT-3′; and forward mutant, 5′-TAGGTGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACCGA-3′) and a universal reverse primer (5′-GTAACTCAGCAGCATCTCAGGG-3′) were previously published by Arcaini et al19 and used with a dual-labeled hydrolysis probe, 6FAM-5′- CCATCAGTTTGAACAGTTGTCTGGATCC-3′-TAMRA (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA). Reactions, 20 μL, contained 0.25 μmol/L forward (WT or mutant) and reverse primer and 0.05 μmol/L hydrolysis probe and 100 ng genomic DNA in one times Quantitect Multiplex (No ROX) Mastermix (Qiagen, Inc.). A real-time PCR was performed on an LC480 instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with a pre-incubation at 95°C for 15 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute (with a single-fluorescence acquisition). Crossing points for all WT (Cpwt) and mutant (Cpmut) PCRs were calculated with the Absolute Quant/Second Derivative Max option of the instrument software. The percentage of mutant V600E allele in a sample was then calculated as follows24:

| (1) |

where E is the PCR efficiency and ΔCp is

| (2) |

The PCR efficiency for both WT and mutant PCRs was determined by generating a standard curve with serially 10-fold diluted pBRAF-WT and pBRAF-HET plasmids. The efficiency was calculated from the slope of the standard curve (cycle number versus the log10 of the plasmid dilution), as follows:

| (3) |

The PCR efficiencies for both WT and mutant PCRs were determined in five separate experiments. The averages ± SD were 1.945 ± 0.013 (WT) and 1.933 ± 0.007 (mutant) and deemed similar enough to be combined into one average value of 1.939. All PCRs were run in duplicate, and the difference in results between duplicates was ≤0.2 crossing points in 87% of reactions and ≤0.4% crossing points in 97% of reactions. The calibrator plasmid was used in a linear configuration unless indicated otherwise.

Pyrosequencing

DNA samples were first amplified for a region of BRAF exon 15 using a biotin-labeled reverse primer. The biotin-labeled strand was then isolated and sequenced on a PyroMark Q24 (Qiagen, Inc.) instrument, according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the sequencing primer 5′-TGATTTTGGTCTAGCTACA-3′ and the dispensation order CAGTACG. Sequence analysis was performed using PyroMark Q24, version 1.0.10, software in the Allele Quantification analysis mode.

Results

We used allele-specific primers for the BRAF V600E mutation and the WT allele, which were previously described,19 and designed a dual-labeled hydrolysis probe to obtain quantitative data. No single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been described in the sequences covered by the primers and probe. The primer design is specific and results in minor cross-allele amplification. DNA samples from 12 healthy donors, without evidence of HCL, yielded an average background signal of 0.013% mutant allele. This background signal plus two times the SD equaled 0.025% mutant allele. We, therefore, arbitrarily set the lower limit of detection (LOD) to 0.2%, which should guarantee a high clinical specificity for this test method.

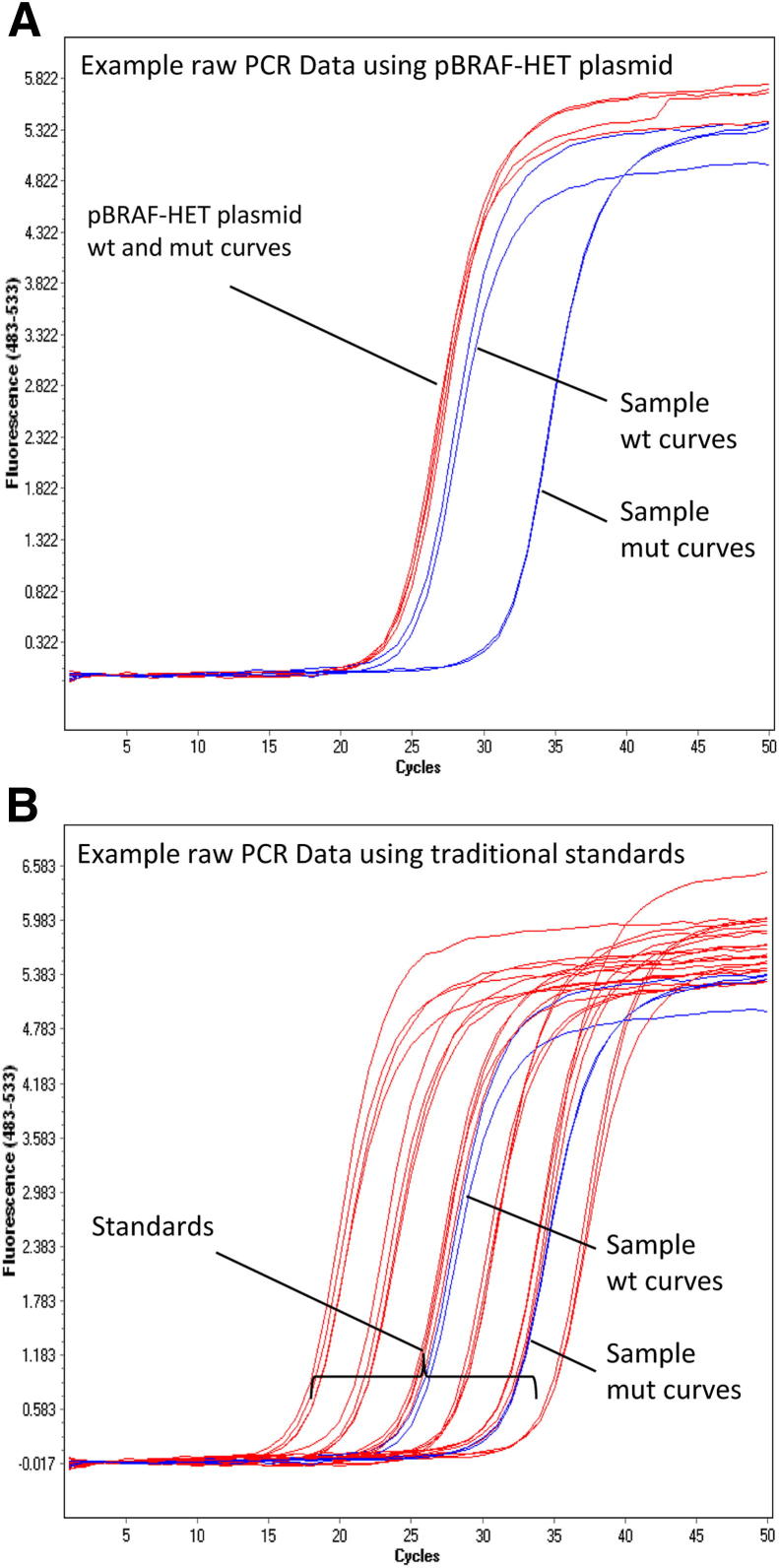

Each PCR run included a calibrator plasmid, pBRAF-HET, that contained both a WT and V600E mutant fragment that covered the region amplified by the test PCR primers. This plasmid was included at a single concentration with each PCR run and represents a perfect heterozygous sample, always representing exactly 50% mutant allele. The WT and mutant crossing points obtained from quantitative allele-specific PCR with the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid, together with the predetermined PCR efficiency, were used to calculate the percentage mutant allele in unknown samples on the same run (see Equation 1). As would be expected for most allele-specific PCR designs, the PCR efficiencies for both the WT and mutant PCRs were similar and could be averaged into one value. The value of this strategy lies in the fact that it does not involve the calculation of absolute copy numbers and, therefore, does not require the generation of standard curves from known copy number standards. Figure 1 illustrates the relative simplicity of a quantitative allele-specific PCR run using the single-concentration pBRAF-HET plasmid calibrator compared with the complexity of a run using traditional standard curve–based methods.

Figure 1.

Illustration of quantitation strategies. Amplification plots for both WT and V600E mutant allele-specific PCRs showing the calibration standards (red) and an unknown sample (blue). A: pBRAF-HET method. B: Conventional standard curve method.

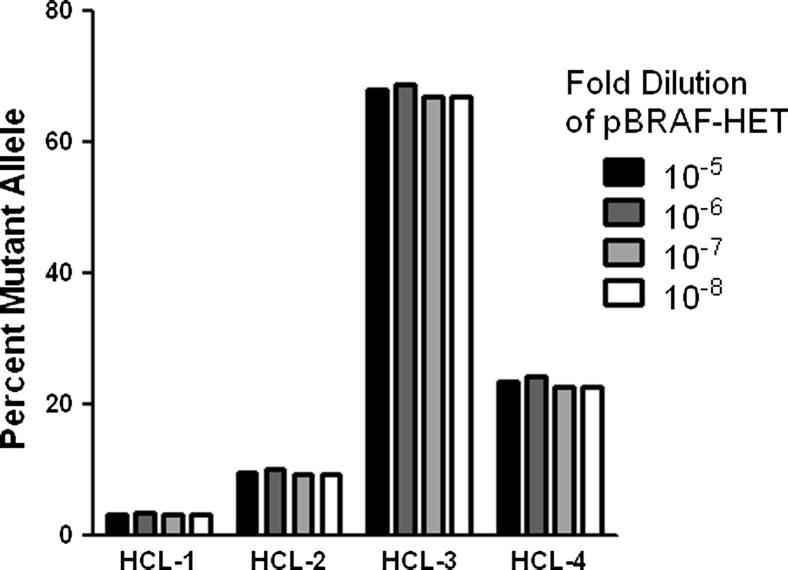

Because the pBRAF-HET plasmid is run at a single concentration, the method relies on extrapolation between differing Cp values using the predetermined PCR amplification efficiency. Therefore, it is possible that samples with mutant allele frequencies that markedly differ from that represented by the pBRAF-HET plasmid, (eg, low or high tumor burden samples) might be quantified inaccurately with this method. Furthermore, it is possible that the concentration of the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid itself could affect allele quantitation. To evaluate these possibilities, we ran the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid at concentrations over a range of three logs and calculated the percentage of mutant allele in samples with varying BRAF V600E allele frequencies independently for each calibrator dilution. Figure 2 demonstrates that this technique yields reproducible quantitation (coefficient of variation, <5%) with high, moderate, and low mutant burdens, regardless of the concentration of the calibrator plasmid. We conclude that the pBRAF-HET calibrator concentration is not critical for accurate allele quantitation. Therefore, this method is not subject to inaccuracies introduced by small pippetting errors that are known to affect the generation of traditional standard curves. The 106-fold dilution of the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid was used throughout the study, which equaled approximately 0.1 pg of plasmid DNA per PCR. This concentration consistently resulted in crossing points similar to those obtained for the WT PCR, with 100 ng of normal genomic DNA (crossing points, approximately 22 to 24 cycles).

Figure 2.

Comparison of different pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid concentrations. The percentage mutant allele was determined as described in Materials and Methods for each HCL sample. Differently shaded bars indicate the concentration of calibrator plasmid used for allele quantitation.

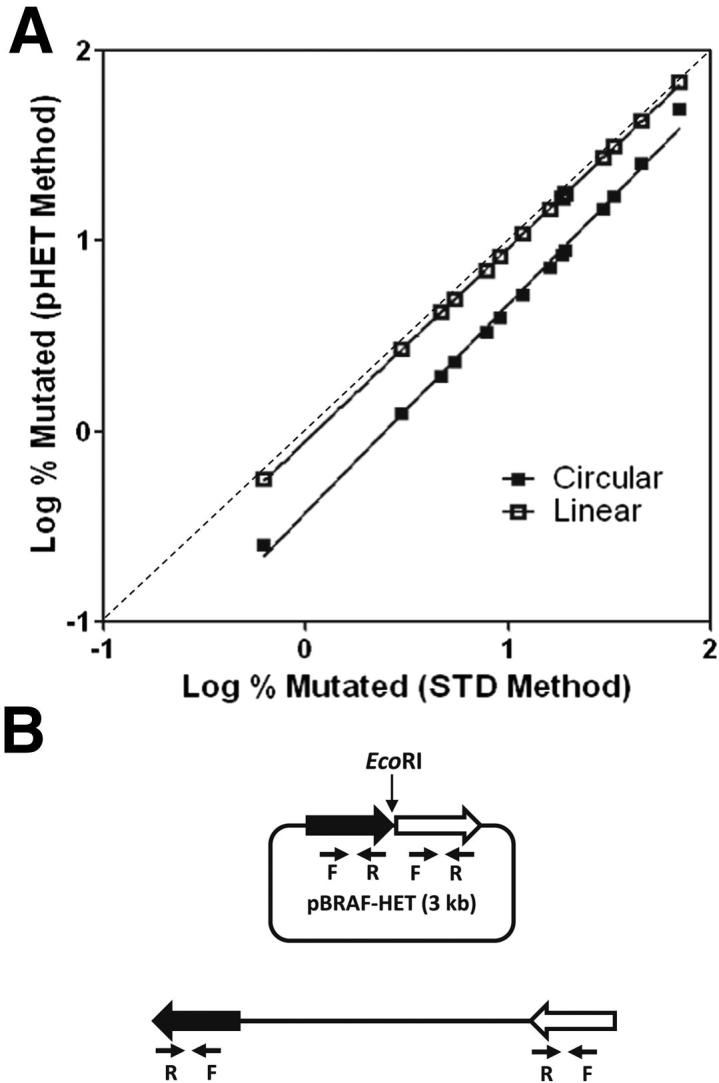

The easiest and most effective way of generating a heterozygous standard is by cloning both WT and mutant alleles into the same plasmid vector. Taking advantage of the multiple cloning sites of the vector, we inserted both WT and V600E mutant sequences as tandem repeats to generate the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid. However, given the close proximity of both alleles in the plasmid, there might be interference during PCR amplification with allele-specific primers. We tested this possibility by separating both fragments using a restriction enzyme to cut at the cleavage site between the WT and mutant inserts, thereby linearizing the plasmid. In the linearized version of the WT and mutant, inserts are separated by 3 kb, the length of the plasmid backbone. Next, we calculated the mutant allele percentages in 14 known HCL samples using both the linear and circular forms of the calibrator plasmid and compared the results with those generated with the use of conventional standard curves, considered the gold standard. Figure 3A shows that there is good agreement over the entire data range between the values generated by the standard curve method and the pBRAF-HET calibrator method using a linearized plasmid (R2 = 0.9999). The values obtained using the circular calibrator plasmid were consistently lower, indicating possible interference from the closely spaced inserts. We, therefore, used the linearized version of the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid depicted in Figure 3B throughout this study. The reproducibility of quantitative PCR data obtained between experiments was also compared between the pBRAF-HET and conventional standard curve methods. Coefficient of variation values for a sample with approximately 0.5% mutant allele burden were 19% (pBRAF-HET method) and 12% (standard curve method). For samples with a higher mutant allele burden, the coefficient of variation values averaged at 4.4% (pBRAF-HET method) and 4.6% (standard curve method).

Figure 3.

Quantitation using linearized versus circular pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid. A: Mutant allele burden for 14 HCL samples was calculated using linear and circular pBRAF-HET calibrator (pHET method) and plotted against data from the same samples calculated with a standard curve–based calculation of mutant allele burden (STD method). Averages from three experiments are shown. B: Schematic of the circular and linear pBRAF-HET plasmid.

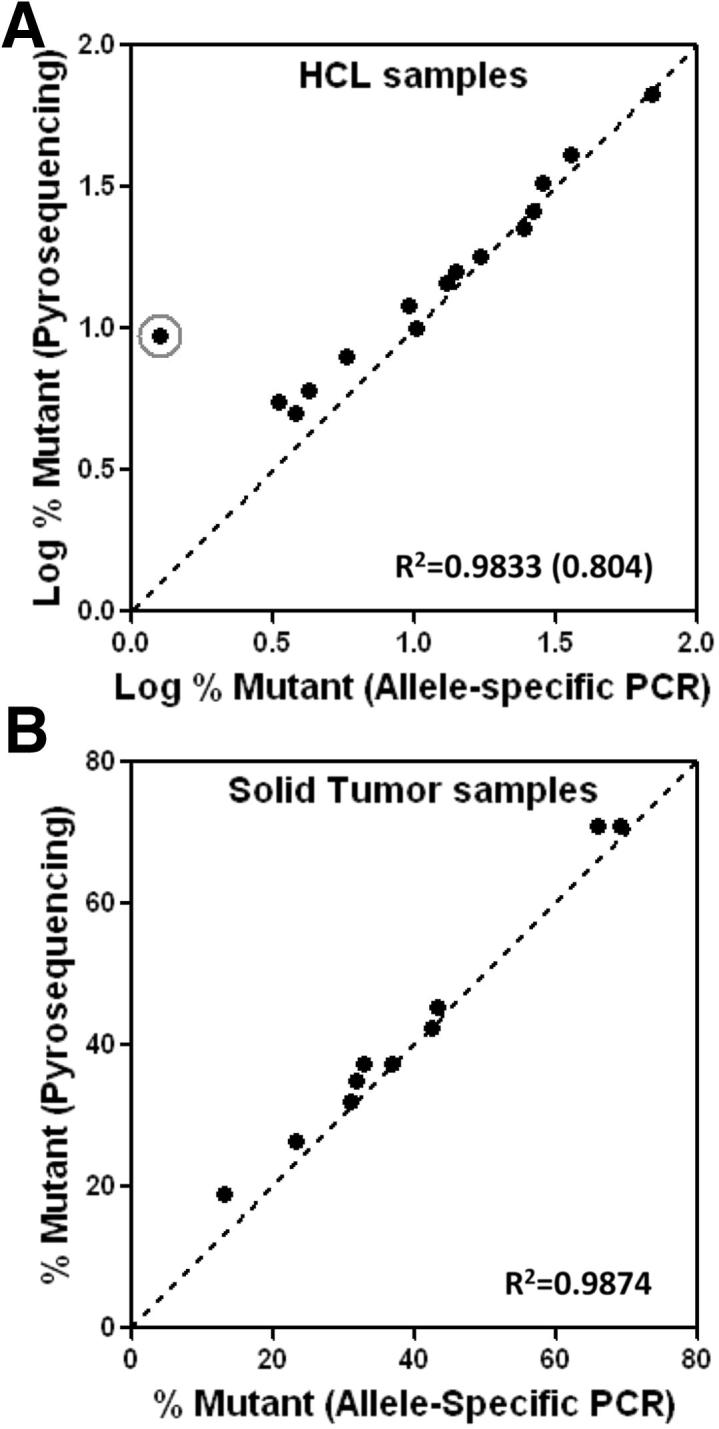

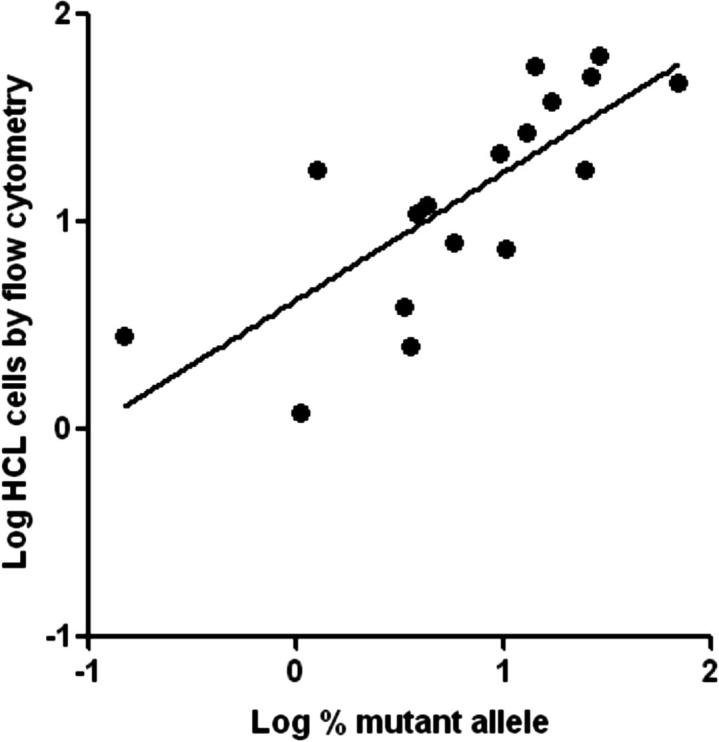

In total, we tested 18 HCL samples, including those previously described for Figure 3A, and obtained data in the range of 0.15% to 69% mutant allele. With the clinical LOD arbitrarily set at 0.2% to ensure high clinical specificity, the single HCL sample with 0.15% mutant allele burden by the pBRAF-HET calibrator method would be considered negative. The quantitation value was corroborated using the standard curve method (0.17%). In addition, four chronic lymphocytic leukemia samples, assumed negative for the BRAF V600 mutation, were tested and yielded values between 0.03% and 0.06% mutant allele. These values would have been appropriately interpreted as negative. The findings are supportive of setting an arbitrary clinical LOD higher than the analytical LOD to ensure clinical confidence. As an additional step in validating the design, we compared the quantitative PCR data derived using the calibrator plasmid with allele quantitation by pyrosequencing, which has a lower LOD of 5% mutant allele. In Figure 4A, we show the comparison with 15 samples that were positive by pyrosequencing (ie, ≥5% mutant allele). There was one discordant HCL specimen that yielded a higher mutant allele burden by pyrosequencing (9.5%) than by allele-specific PCR (1.26%). For the remaining specimens, there was good correlation (R2 = 0.9833). Of the HCL specimens that were negative by pyrosequencing, one was also negative by allele-specific PCR (previously discussed), and the others yielded 1.05% and 3.51% mutant allele. To validate the general applicability of the method to samples other than peripheral blood and bone marrow, we also showed data for 15 FFPE solid tumor samples, in which the BRAF V600E mutation might also occur (six melanomas, five colon carcinomas, and four thyroid carcinomas). In Figure 4B, we demonstrate data from 10 of the samples that were positive by pyrosequencing. The correlation between pyrosequencing and allele-specific PCR using pBRAF-HET was excellent (R2 = 0.9874). Of the remaining five FFPE samples that were negative for BRAF V600E by pyrosequencing, four were also negative by our allele-specific PCR method and one demonstrated low-level positivity (0.82% mutant allele), well lower than the LOD for pyrosequencing. We further compared the allele-specific PCR data with the estimated number of HCL cells in these specimens, obtained by flow cytometric analysis. Figure 5 shows a trend that correlates leukemia cell number with BRAF V600E allele burden. The cell numbers are generally higher than the determined mutant allele burden, suggesting the heterozygous status of the mutation. The HCL specimen that yielded discordant values between allele-specific PCR and pyrosequencing harbored 18% HCL cells, corroborating the pyrosequencing result.

Figure 4.

Comparison of quantitation with the pBRAF-HET calibrator plasmid to pyrosequencing. Comparison of allele quantitation by allele-specific PCR and pyrosequencing for HCL specimens with R2 values shown without (and with) the circled discordant HCL case (A) and solid tumor specimens that were within the range of positivity (≥5% mutant allele) by pyrosequencing with R2 values shown (B).

Figure 5.

Correlation of BRAF V600E allele burden using pBRAF-HET with HCL cell count. BRAF V600E mutant allele burden is compared with the HCL cell count estimated from flow cytometry data. Log-transformed data are shown.

Discussion

We describe a quantitative allele-specific PCR assay that uses a novel method for calculating allele ratios, and we have used BRAF V600E allele quantitation as a means of demonstrating its utility. This method does not use copy number calculation using WT and mutant allele standard curves; instead, it uses a heterozygous plasmid calibrator with an allele ratio of exactly 1:1. The data obtained with this calibrator plasmid, which is run at a single concentration, together with predetermined PCR efficiencies are then used to calculate the allele frequencies of unknown samples on the same PCR run. This method greatly simplifies the experimental layout and yields results that highly correlate to those obtained by quantifying the mutant alleles using conventional standard curves. As proof of principle, we tested a series of HCL specimens and found close agreement between this and standard curve–based allele quantitation over a greater than two-log range of BRAF V600E mutant allele burden (R2 = 0.9999). Although the heterozygous calibrator plasmid is run at a single concentration, our data clearly show that it generates accurate data over a wide range of allele ratios. In addition, varying the calibrator plasmid concentration over a range of three logs yields nearly identical allele ratios. Taken together, our data indicate that extrapolation of the mutant allele burden from a heterozygous calibrator run at a single concentration yields quantitative data that are equivalent to standard curve–based methods. An additional advantage is that this technique greatly simplifies the PCR layout, allowing for more samples to be included in a single run without compromising the accuracy of the data.

The method does require careful determination of the PCR efficiencies, and this should be performed in every design where this strategy is used. We have not tested different primer lots, but we anticipate that the PCR efficiency will need to be reconfirmed with new lots of primers. The PCR efficiency is determined with serially diluted plasmids and this step, too, does not require the knowledge of absolute copy numbers. In the test described herein, the PCR efficiencies for both WT and mutant PCRs are similar and are averaged into a single value. This is generally expected for most allele-specific PCR designs because both PCRs are nearly identical. The fact that widely varying calibrator plasmid concentrations yield similar results also indicates that the combined PCR efficiency for both WT and mutant PCRs is accurate and that the results are not skewed by the degree of difference in Cp values between the calibrator and an unknown sample.

The heterozygous calibrator plasmid used in this assay has a tandem head-to-tail arrangement of WT and mutant BRAF fragments, and we observed some PCR interference between the repeated fragments. We do not know the exact nature of the interference, but it can be avoided by linearizing the plasmid between the two repeats, thereby separating the two inserts by 3 kbp, the length of the vector backbone. We have not investigated if an inverted repeat arrangement would also avoid the observed PCR interference, but linearization of the calibrator plasmid between the two inserts is a simple solution to any interference issues.

We further validated the accuracy of the allele-specific method against pyrosequencing, and good correlation was observed between the different methods. In all of our comparisons with pyrosequencing, using both HCL and solid tumor specimens, we only found one slightly discordant case, an HCL sample that demonstrated 9.5% mutant allele by pyrosequencing and 1.26% mutant allele by allele-specific PCR. Although no known germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been reported at the primer and probe binding sites, we hypothesize that the mutant allele in the discordant sample harbors an additional mutation at positions affecting amplification or detection of the PCR product. However, with a BRAF V600E mutant allele frequency of <10%, any accompanying mutations are lower than the detection limits for traditional Sanger sequencing and, thus, we could not confirm this hypothesis. Our comparison also included FFPE tissue samples from various BRAF mutation–positive solid tumor specimens. The BRAF V600E mutant burden in these samples was mostly >30% because the tumors had been microdissected from slides before DNA extraction to increase overall sensitivity. Interestingly, one such specimen, a melanoma, was negative by pyrosequencing, but positive by our allele-specific PCR method (0.82% mutant allele). Although BRAF mutations are considered to be an early event in tumorigenesis, this may be an example of tumor heterogeneity or selection in melanoma, as recently reported.4 The sensitivity of this method versus sequencing would make it suitable for analyzing heterogeneity within a tumor or tumor metastases.

Allele-specific PCR assays are suitable for detecting a single or predominant recurring base substitution. A growing number of reports have identified only the c.1799 T>A (p.V600E) mutation in HCL,19, 20, 21, 22 and our test format should, therefore, identify most positive cases. In solid tumors that harbor BRAF codon 600 mutations, additional rarer mutations, other than V600E, have been observed.15 Most of those mutations will not be detected by the described allele-specific PCR design, even if the 3′-most base of the mutant primer is properly paired (V600K, GTG>AAG), because of the additional mismatch at position −2 in the assay design. Exceptions are the V600D (GTG>GAY) and alternate V600E (GTG>GAA) mutations, which should allow the correct base pairing with the mutant primer, assuming that any additional base changes outside the primer binding site do not affect the PCR efficiency.

The main advantage of this heterozygous calibrator plasmid-based allele quantitation method is that known copy number standards are unnecessary. This provides efficiency gains over traditional methods because the copy number of traditional standards must be determined with every new lot, whereas the heterozygous calibrator plasmid is simply isolated from a bacterial stock, linearized, and diluted to an approximate concentration. A heterozygous control, such as the calibrator described herein, is internally controlled and would likely enhance interlaboratory standardization efforts. High-quality PCR master mixes for hydrolysis probe-based quantitation are commercially available and, when universally used, would further simplify interlaboratory harmonization of quantitative allele-specific PCR designs. Other performance characteristics of this test, such as analytical sensitivity and reproducibility, are also comparable to conventional standard curve–based quantitation. This method, therefore, provides a simple, robust, and economical alternative for laboratory-derived quantitative allele-specific PCR designs.

Footnotes

Supported by ARUP Laboratories, an enterprise of the Department of Pathology, University of Utah.

P.S. and N.S.R. contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bottema C.D., Sommer S.S. PCR amplification of specific alleles: rapid detection of known mutations and polymorphisms. Mutat Res. 1993;288:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90211-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barosi G., Bergamaschi G., Marchetti M., Vannucchi A.M., Guglielmelli P., Antonioli E., Massa M., Rosti V., Campanelli R., Villani L., Viarengo G., Gattoni E., Gerli G., Specchia G., Tinelli C., Rambaldi A., Barbui T., Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) Italian Registry of Myelofibrosis JAK2 V617F mutational status predicts progression to large splenomegaly and leukemic transformation in primary myelofibrosis. Blood. 2007;110:4030–4036. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tefferi A., Strand J.J., Lasho T.L., Knudson R.A., Finke C.M., Gangat N., Pardanani A., Hanson C.A., Ketterling R.P. Bone marrow JAK2V617F allele burden and clinical correlates in polycythemia vera. Leukemia. 2007;21:2074–2075. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin J., Goto Y., Murata H., Sakaizawa K., Uchiyama A., Saida T., Takata M. Polyclonality of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma and the selection of mutant alleles during progression. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:464–468. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santarpia L., Lippman S.M., El-Naggar A.K. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2012;16:103–119. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.645805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brose M.S., Volpe P., Feldman M., Kumar M., Rishi I., Gerrero R., Einhorn E., Herlyn M., Minna J., Nicholson A., Roth J.A., Albelda S.M., Davies H., Cox C., Brignell G., Stephens P., Futreal P.A., Wooster R., Stratton M.R., Weber B.L. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6997–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies H., Bignell G.R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura E.T., Nikiforova M.N., Zhu Z., Knauf J.A., Nikiforov Y.E., Fagin J.A. High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xing M., Westra W.H., Tufano R.P., Cohen Y., Rosenbaum E., Rhoden K.J., Carson K.A., Vasko V., Larin A., Tallini G., Tolaney S., Holt E.H., Hui P., Umbricht C.B., Basaria S., Ewertz M., Tufaro A.P., Califano J.A., Ringel M.D., Zeiger M.A., Sidransky D., Ladenson P.W. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6373–6379. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kebebew E., Weng J., Bauer J., Ranvier G., Clark O.H., Duh Q.Y., Shibru D., Bastian B., Griffin A. The prevalence and prognostic value of BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:466–470. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318148563d. discussion 470-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fariña-Sarasqueta A., van Lijnschoten G., Moerland E., Creemers G.J., Lemmens V.E., Rutten H.J., van den Brule A.J. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2396–2402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaherty K.T., Hodi F.S., Bastian B.C. Mutation-driven drug development in melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:178–183. doi: 10.1097/cco.0b013e32833888ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiacci E., Trifonov V., Schiavoni G., Holmes A., Kern W., Martelli M.P. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2305–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xi L., Arons E., Navarro W., Calvo K.R., Stetler-Stevenson M., Raffeld M., Kreitman R.J. Both variant and IGHV4-34-expressing hairy cell leukemia lack the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2012;119:3330–3332. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnett M.J., Marais R. Guilty as charged: b-RAF is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughn C.P., Zobell S.D., Furtado L.V., Baker C.L., Samowitz W.S. Frequency of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:307–312. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd E.M., Bench A.J., van’t Veer M.B., Wright P., Bloxham D.M., Follows G.A., Scott M.A. High resolution melting analysis for detection of BRAF exon 15 mutations in hairy cell leukaemia and other lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:609–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blombery P.A., Wong S.Q., Hewitt C.A., Dobrovic A., Maxwell E.L., Juneja S., Grigoriadis G., Westerman D.A. Detection of BRAF mutations in patients with hairy cell leukemia and related lymphoproliferative disorders. Haematologica. 2012;97:780–783. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.054874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcaini L., Zibellini S., Boveri E., Riboni R., Rattotti S., Varettoni M., Guerrera M.L., Lucioni M., Tenore A., Merli M., Rizzi S., Morello L., Cavalloni C., Da Via M.C., Paulli M., Cazzola M. The BRAF V600E mutation in hairy cell leukemia and other mature B-cell neoplasms. Blood. 2012;119:188–191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-368209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langabeer S.E., O’Brien D., Liptrot S., Flynn C.M., Hayden P.J., Conneally E., Browne P.V., Vandenberghe E. Correlation of the BRAF V600E mutation in hairy cell leukaemia with morphology, cytochemistry and immunophenotype. Int J Lab Hematol. 2012;34:417–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnittger S., Bacher U., Haferlach T., Wendland N., Ulke M., Dicker F., Grossmann V., Haferlach C., Kern W. Development and validation of a real-time quantification assay to detect and monitor BRAFV600E mutations in hairy cell leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:3151–3154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiacci E., Schiavoni G., Forconi F., Santi A., Trentin L., Ambrosetti A., Cecchini D., Sozzi E., Francia di Celle P., Di Bello C., Pulsoni A., Foa R., Inghirami G., Falini B. Simple genetic diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia by sensitive detection of the BRAF-V600E mutation. Blood. 2012;119:192–195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-371179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newell J.O., Cessna M.H., Greenwood J., Hartung L., Bahler D.W. Importance of CD117 in the evaluation of acute leukemias by flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2003;52:40–43. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]