Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents the fastest growing pathology worldwide with a prevalence of >10% in many countries. In addition, kidney cancer represents 5% of all new diagnosed cancers. As currently no effective therapies exist to restore kidney function after CKD- as well as cancer-induced renal damage, it is important to elucidate new regulators of kidney development and disease as new therapeutic targets. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the most successful class of pharmaceutical targets. In recent years adhesion GPCRs (aGPCRs), the second largest GPCR family, gained significant attention as they are present on almost all mammalian cells, are associated to a plethora of diseases and regulate important cellular processes. aGPCRs regulate for example cell polarity, mitotic spindle orientation, cell migration, and cell aggregation; all processes that play important roles in kidney development and/or disease. Moreover, polycystin-1, a major regulator of kidney development and disease, contains a GAIN domain, which is otherwise only found in aGPCRs. In this review, we assess the potential of aGPCRs as therapeutic targets for kidney disease. For this purpose we have summarized the available literature and analyzed data from the databases The Human Protein Atlas, EURExpress, Nephroseq, FireBrowse, cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics and the National Cancer Institute Genomic Data Commons data portal (NCIGDC). Our data indicate that most aGPCRs are expressed in different spatio-temporal patterns during kidney development and that altered aGPCR expression is associated with a variety of kidney diseases including CKD, diabetic nephropathy, lupus nephritis as well as renal cell carcinoma. We conclude that aGPCRs present a promising new class of therapeutic targets and/or might be useful as diagnostic markers in kidney disease.

Keywords: kidney, adhesion G protein-coupled receptor, renal cell carcinoma, chronic kidney disease, lupus nephritis, diabetic nephropathy

Kidney function

The main function of the kidney is to filter the blood while conserving water and maintaining the electrolyte homeostasis. A part of the filtrate is excreted (e.g., urea, ammonium, uric acid, metabolic waste, toxins) and another part is reabsorbed (e.g., solute-free water, sodium, bicarbonate, glucose, calcium, phosphate, and amino acids). In addition, the kidney has other functions such as gluconeogenesis, converting a precursor of vitamin D to its active form, and synthesizing the hormones erythropoietin and renin. This way the kidney regulates the volume of various body fluid compartments, fluid osmolality, acid-base balance, various electrolyte concentrations, removal of toxins and participates in the intermediary metabolism.

The structural and functional unit of the kidney is the nephron which consists of a renal corpuscle and a renal tubule (Figure 1A; Romagnani et al., 2013). The renal corpuscle contains a tuft of capillaries (glomerulus) and the Bowman's capsule. The renal tubule extends from the capsule and has five anatomically and functionally different segments: the proximal tubule (proximal convoluted tubule followed by the proximal straight tubule), the loop of Henle (descending and ascending loop), the distal convoluted tubule, the connecting tubule, and the collecting duct. Blood filtration occurs in the glomerulus through two cell layers, fenestrated endothelial cells and podocytes, as well as their individual laminae and the basal membrane they both share. Resorption takes place via peritubular capillaries while the fluid flows from the Bowman's capsule down the tubule. The urine, final product of blood filtration, runs from the collecting ducts through the renal papillae, calyces, pelvis, and finally via the ureter into the urinary bladder.

Figure 1.

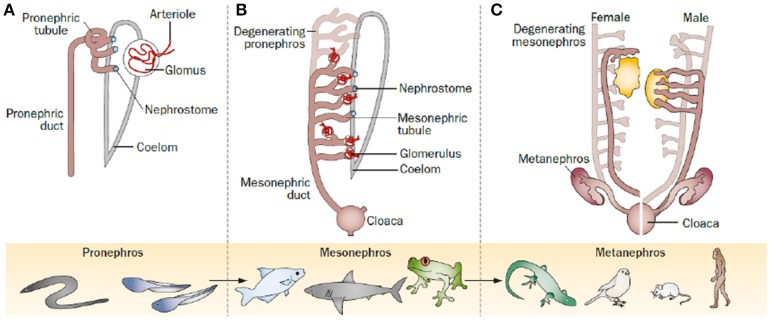

The kidney through evolution, as it proceeded through a series of successive phases, each marked by the development of a more advanced kidney: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros. (A) The pronephros is the most immature form of kidney; it represents the first stage of kidney development in most animal species, but became functional only in ancient fish, such as lampreys or hagfish, or during the larval stage of amphibians. (B) The mesonephros represents the second stage of kidney development in most animal species, and represents the functional mature kidney in most fish and amphibians. It is made up of an increased number of nephrons, usually dozens to hundreds. (C) The metanephros represents the last stage of kidney development after degeneration of the pronephros and mesonephros in reptiles, birds and mammals, where it persists as the definitive adult kidney; it consists of a substantially increased number of nephrons, usually from thousands to millions. Romagnani et al. progenitors: an evolutionary conserved strategy for kidney regeneration. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: (Romagnani et al., 2013).

Kidney development

Due to different surrounding environments and thus different requirements on renal function, kidneys passed through different adaptive designs along evolution. Ultimately, this led to the intricate structures in the mammalian kidney. The kidney arises from the intermediate mesoderm and proceeds through three successive developmental phases representing different evolutionary patterns: pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros (Figure 1; Saxén et al., 1986). The first evidence of kidney organogenesis is the formation of a primary nephric (pronephric) duct. As it grows caudally, a linear array of epithelial tubules forms and extends medioventrally giving rise to an anterior rudimentary pronephros, in which the tubules are not yet directly linked with the capillary tuft (Romagnani et al., 2013). The pronephros (Figure 1A) is active in embryos of fish and larvae of amphibians as well as in some adult primitive fish. In more advanced vertebrates, the pronephros is frequently nonfunctional and soon replaced by the mesonephros. The anterior part of the pronephric duct degenerates while the caudal portion persist and serves as the central component of the excretory system (mesonephric or Wolffian duct). The middle portion induces another set of tubules, the mesonephros (Figure 1B), which is in mammals the source of hematopoietic stem cells. Subsequently, the mesonephros either regresses or becomes sperm-carrying tubes (epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicles) in male individuals. In amphibians and most fish the mesonephros represents the permanent kidney, while in mammals, birds, and reptiles the mesonephros regresses and the metanephros is formed.

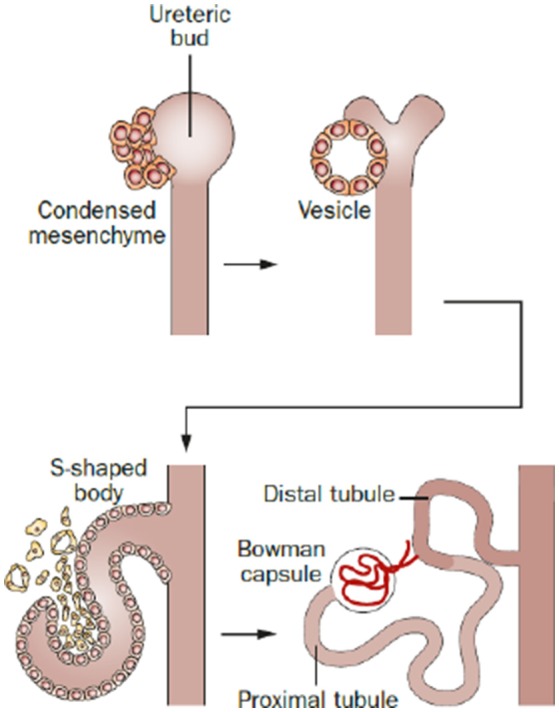

The metanephros (Figure 1C) is the permanent kidney in reptiles, birds, and mammals. It develops from a caudal diverticulum of the Wolffian duct, which is induced to branch by signals from the surrounding metanephric mesenchyme. This epithelial branch is called ureteric bud (Schmidt-Ott et al., 2005; Dressler, 2008). The ureteric bud epithelia proliferate, migrate, and gradually invade the metanephric mesenchyme as it undergoes branching morphogenesis (Watanabe and Costantini, 2004), which is mediated by glial-derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf). Gdnf is released by metanephric mesenchymal cells and binds to the Ret receptor on epithelial ureteric bud cells inducing migration, invasion and branching (Towers et al., 1998; Costantini, 2010). In the end, the ureteric bud branches from the collecting system of the kidney (bladder trigone, ureters, renal pelvis, and collecting ducts), which is controlled by multiple patterning factors such as c-Ret, Spry1, ETv5, Robo2, Sox9, Wnt11, Angiotensin II, Fgfr2, Bmp4, At1r, FoxC2, and Pax2 (Yosypiv, 2008; Yosypiv et al., 2008; Reidy and Rosenblum, 2009; Faa et al., 2012). Surrounding the tips of the ureteric bud, metanephric mesenchymal cells condensate and aggregate into the so-called cap mesenchyme, a process mainly driven by Pax2 and Wnt4 (Sariola, 2002; Figure 2). Afterwards, the cap mesenchyme progressively undergoes mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) forming the renal vesicles (Carroll et al., 2005) via Wnt4, Lhx1, and Fgf8 signaling and downregulation of Six2 and Cited2 expression (Kispert et al., 1998; Davies, 1999; Brunskill et al., 2008). Subsequently, the vesicles undergo segmentation patterning followed by fusion with the ureteric branches to form a uriniferous tubule (Georgas et al., 2009). During the following development, renal vesicles change their appearance and proceed through the stages comma-shaped body, S-shaped body and capillary loop stage (Little et al., 2007). During these stages, markers for proximal and distal tubules of the future nephron start to be expressed, and the primitive glomeruli evolve by incorporating vascular loops and allowing endothelial cells to get in contact with visceral epithelial cells (early podocytes) forming the glomerular filtration barrier. Transcription factors such as Wt1 and Pod1 play a central role during this process of morphogenesis (Rico et al., 2005). Interstitial cells and vasculature are formed from a multipotent pool of progenitor cells in the metanephric mesenchyme (Kispert et al., 1998).

Figure 2.

Phases of nephron development in all animals. The metanephric mesenchyme condenses around the ureteric bud and is induced to convert into epithelium and generates in sequence a vesicle and an S-shaped body. Then, the S-shaped body becomes invaded by blood vessels at one extremity and elongates and segmentates at the other, thus generating the whole nephron. This sequence of events is similar during development across all animal species. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: (Romagnani et al., 2013).

Resemblance of adhesion G protein-coupled receptors (aGPCRs) and polycystin-1

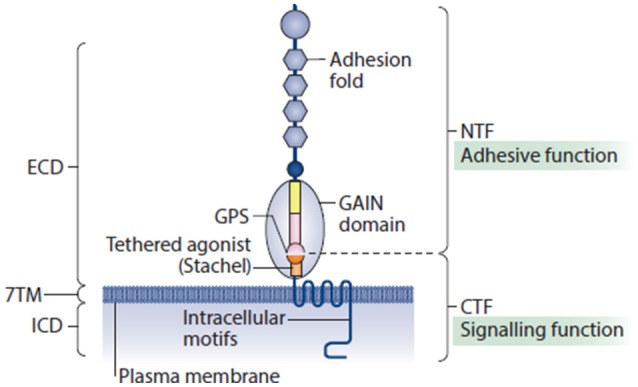

aGPCRs represent one of five families of the GPCR superfamily, the largest group of membrane receptors in eukaryotes. In humans, the aGPCR family contains 33 members which can be subdivided into 9 subfamilies (I to IX) (Hamann et al., 2015). They are characterized by a long extracellular domain which comprises several adhesion domains, a 7 transmembrane domain and an intracellular domain. The extended N-terminus can be cleaved in almost all aGPCRs at the so-called GPCR proteolysis site (GPS) within the GPCR autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain (Figure 3). This property permits a variety of signaling modalities including activation of CTF-dependent or -independent signals via agonist interactions at the NTF or the CTF. In addition, NTF can bind either to partners at the surface of a neighboring cell or the extracellular matrix. Yet, the NTF can also be shed off to induce non-cell-autonomous signals in neighboring or in distant cells (Langenhan et al., 2013; Patra et al., 2013, 2014). However, some aGPCRs containing a GPS motif do not undergo cleavage [e.g., ADGRC1 (CELSR1), ADGRF4 (GPR115), ADGRF2 (GPR111)]. ADGRA1 (GPR123) is the only aGPCR that does not contain a GAIN domain (Hamann et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors possess structural elements of adhesion molecules and GPCRs. Their extended extracellular domain (ECD) usually contains a collection of adhesion motifs that can engage with cellular and matricellular interaction partners, and a juxtamembrane GPCR autoproteolysis-inducing (GAIN) domain, which is present in all aGPCRs. GAIN subdomain A (yellow rectangle), GAIN subdomain B (pink rectangle) and the GPCR proteolysis site (GPS) motif (pink and orange semicircles) are shown. The GAIN domain is directly connected to the seven-transmembrane (7TM) unit through a linker sequence of approximately 20 amino acids, known as the Stachel (stalk). Recently, this structural component of aGPCRs was identified as a tethered agonist, which stimulates metabotropic activity of several aGPCR homologs. Similar to the ECD, the intracellular domains (ICDs) of aGPCRs can be unusually large. It is estimated that more than one-half of all known aGPCRs undergo auto-proteolytic cleavage that is catalyzed through the GAIN domain, which is present on the cell surface as a non-covalent heterodimer between an amino-terminal fragment (NTF) and a carboxy-terminal fragment (CTF). The cleavage occurs at the evolutionarily highly conserved GPS. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: (Langenhan et al., 2016).

GPCRs are of great clinical interest as they play an important role in the development of pharmacological-based therapies (Lagerström and Schiöth, 2008; Nieto Gutierrez and McDonald, 2017). In addition, aGPCRs are widely expressed (Hamann et al., 2015), play critical roles in many developmental processes (Luo et al., 2011; Geng et al., 2013; Ludwig et al., 2016; Musa et al., 2016; Sigoillot et al., 2016), and are also involved in a variety of diseases. For example, aGPCRs are involved in the control of innate effector functions and the susceptibility for and onset of (auto)inflammatory conditions (Lin et al., 2017), in tumorigenesis (Aust et al., 2016), and pulmonary disease (Ludwig et al., 2016), and they are linked to psychiatric disorders (Lanoue et al., 2013). Yet, little is known about the downstream signaling mechanisms of aGPCRs. In recent years, however, evidence has been provided that aGPCRs can control cell polarity (Strutt et al., 2016), mitotic spindle orientation (Müller et al., 2015), cell migration (Valtcheva et al., 2013; Strutt et al., 2016), and cell aggregation (Hsiao et al., 2011) and that they serve as mechanosensors (Scholz et al., 2016). These are all processes that also play important roles in kidney development and disturbance of these processes are known to contribute to kidney disease (Sariola, 2002; Schordan et al., 2011; Cabral and Garvin, 2014; Xia et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2017; Kunimoto et al., 2017). Thus, we wondered whether also aGPCRs might play a role in renal physiology and pathophysiology to determine their potential as therapeutic targets for kidney disease.

As detailed below, the importance of aGPCRs in kidney development is underlined by initial reports in the literature. Moreover, it is intriguing that the 11 transmembrane domain receptor polycystin-1, a major regulator of kidney development and disease, is the only GAIN-domain containing protein known so far that does not belong to the aGPCR family (Cai et al., 2014). Polycystin-1 plays a role in renal tubular development and functions in a complex with polycystin-2 as a fluid shear sensor. Mutations in the corresponding genes, Pkd1 and Pkd2, have been associated with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (Ferreira et al., 2015). Furthermore, it has been shown that autoproteolytic cleavage at a GPS motif is required for polycystin-1 trafficking to cilia and that only a cleavable form of polycystin-1 can rescue the embryonically lethal Pkd1-null mutation in mice (Cai et al., 2014).

Search strategy

In order to determine what has so far been made publically available in regards to the role of aGPCRs in kidney development and disease, we performed a literature search using Pubmed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). Search terms included “kidney” or “renal,” “development,” “disease” and/or the official or alternative individual names of every aGPCR. In addition, we cross-checked our literature search results with the literature information available in the IUPHAR/BPS database (http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/). Moreover, we performed a comprehensive search utilizing Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.de/), Google (https://www.google.de/) and Google images (https://images.google.de/). Finally, we analyzed the following databases:

The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). The Human Protein Atlas (HPA) is a Swedish-based program that aims “to map all the human proteins in cells, tissues and organs using integration of various Omics technologies, including antibody-based imaging, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, transcriptomics and systems biology” (Uhlén et al., 2015; Uhlen et al., 2017; Thul et al., 2017). For our review we utilized the “Tissue Atlas” that shows the distribution of proteins across all major tissues and organs in the human body including the kidney. The provided data are based on RNAseq and immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays revealing spatial distribution, cell type specificity and the rough relative abundance of proteins in these tissues.

EURExpress (http://www.eurexpress.org/ee/) (Diez-Roux et al., 2011). The EURExpress database provides RNA expression patterns by means of in situ hybridization on paraffin-embedded sections, gelatin-embedded sections and cryosections from E14.5 wild type murine embryos. For some genes, data are also available for other embryonic stages. Note, that this database is not fully annotated, fails to indicate in several cases organs exhibiting a positive expression signal, and does not always provide the necessary resolution to associate the expression pattern with a distinct cell type.

Nephroseq (https://www.nephroseq.org/resource/login.html) (November 2017, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). Nephroseq is a platform that allows integrative data mining of publicly available renal developmental (human) as well as renal disease (model as well as clinical) gene expression data sets which are gathered and curated by an experienced team of data scientists, bioinformaticians, and nephrologists. Thus, it allows identifying genes associated with known disease phenotypes to obtain a better understanding of its role in renal physiology and pathophysiology. In regards to healthy adult kidneys it provides microarray-based information from 5 samples regarding the enrichment of a gene in one of the following compartments: glomeruli, inner renal cortex, inner renal medulla, outer renal cortex, outer renal medulla, papillary tips, and renal pelvis (Higgins et al., 2004). Here, we considered genes as significantly regulated if the p-value was <0.05.

FireBrowse (http://firebrowse.org/). FireBrowse is a platform that enables an efficient analysis of a possible association of a candidate gene with cancer based on DNA and RNA sequence data. The platform accesses Broad Institute's TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) GDAC (Genome Data Analysis Center) Firehose database, “one of the deepest and most integratively characterized open cancer datasets in the world” (over 80,000 sample aliquots from >11,000 cancer patients, spanning 38 unique disease cohorts). Here, we highlight information on >2.5-fold change of RNA expression. Note, no p-values are available.

cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org/) (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013). cBioPortal (cBio) is another platform based on TCGA to associate candidate genes with cancer based on data from 168 cancer studies. It comprises DNA copy-number data, mRNA and microRNA expression data, non-synonymous mutations, protein-level and phosphoprotein level (RPPA) data, DNA methylation data, and limited de-identified clinical data.

National Cancer Institute Genomic Data Commons data portal (NCIGDC) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Similar to the two databases above, NCIGDC allows based on TCGA the association of candidate genes with cancer based on 32,555 cases. Data are provided for 22,144 genes including 3,115,606 mutations.

Our analysis revealed that the majority of the 33 human aGPCRs and several orthologues have been in some aspect related to kidney development or disease (Tables 1, 2) as detailed below.

Table 1.

Adhesion GPCRs associated to kidney development.

| aGPCR | References | Database | Expression | Spatio-temporal information | Gain/loss of function | Function/phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adgrl1 | Masiero et al., 2013 | HPA | IHC, NB | adult (human: tubules) | - | - |

| Adgrl2 | Sugita et al., 1998; Ichtchenko et al., 1999; Masiero et al., 2013 | - | NB | adult (human, rat) | - | - |

| Adgrl3 | - | HPA, NS | IHC, microarray | adult (human: tubules, glomerulus) | - | - |

| Adgrl4 | Nie et al., 2012 | EX, HPA | IF, IHC, ISH, reporter line | embryonic (E10.5 mouse: vessels; E14.5 mouse), adult (human vessels) | KO and double KO mouse (with Adgrf5) | glomerular thrombotic angiopathy |

| Adgre1 | - | NS | microarray | adult (human: glomerulus) | - | - |

| Adgre2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgre3 | HPA | IHC | adult (human: tubular cells) | - | - | |

| Adgre4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgre5 | Hamann et al., 1996; Qian et al., 1999; de la Lastra et al., 2003; Formstone et al., 2010; Toomey et al., 2014 | HPA, NS | IF, IHC, NB, RT-PCR, microarray, reporter line | embryonic (E14.5 mouse: collecting system), juvenile (4-month-old mouse: podocytes, mesangial cells), adult (zebrafish/ pig/ human: glomerulus, pelvis/ mouse: mesangial cells) | KO mouse | - |

| Adgra1 | Formstone et al., 2010 | - | RT-PCR | adult (zebrafish) | - | - |

| Adgra2 | Huang et al., 2008 | EX, NS | ISH, RT-PCR, microarray | embryonic (E14.5 mouse), adult (rat/ human: pelvis) | - | - |

| Adgra3 | - | EX, HPA | IHC, ISH | embryonic (E14.5 mouse: nephrogenic cortex), adult (human: tubular cells) | - | - |

| Adgrc1 | Formstone et al., 2010; Yates et al., 2010a; Brzoska et al., 2016 | EX, HPA | IF, IHC, ISH, RT-PCR | embryonic (E14.5 mouse, E18.5 mouse: podocytes, proximal tubule, collecting duct stalks, S-shaped body); adult (zebrafish/ human: vessels) | Mice carrying a loss of function mutation | ureteric bud branching |

| Adgrc2 | - | EX, HPA, NS | IHC, ISH, microarray | embryonic (E14.5 mouse), adult (human: medulla) | - | - |

| Adgrc3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgrd1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgrd2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgrf1 | Alva et al., 2006; Prömel et al., 2012 | HPA, NS | IHC, RT-PCR, microarray, reporter line | adult (human: glomerulus, papillary tips) | KO mouse | - |

| Adgrf2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgrf3 | - | NS | microarray | adult (human: glomerulus) | - | - |

| Adgrf4 | Alva et al., 2006 | - | RT-PCR, reporter line | - | KO mouse | - |

| Adgrf5 | Alva et al., 2006; Nie et al., 2012 | NS | IF, RT-PCR, microarray | embryonic (E12.5 mouse: vessels), adult (human: cortex, medulla, papillary tips/ mouse: glomerulus) | KO and double KO mouse (with Adgrl4) | glomerular thrombotic angiopathy |

| Adgrb1 | Calderón-Zamora et al., 2017 | - | IHC, RT-PCR | adult (human) | - | - |

| Adgrb2 | - | HPA, NS | IHC, microarray | adult (human: tubules, pelvis) | - | - |

| Adgrb3 | - | NS | microarray | adult (human: glomerulus) | - | - |

| Adgrg1 | Matsushita et al., 1999; Shashidhar et al., 2005 | EX, NS | ISH, NB, WB, microarray | embryonic (E12 mouse: ureteric branches), adult (human: cortex) | - | - |

| Adgrg2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgrg3 | Formstone et al., 2010 | - | RT-PCR | adult (zebrafish) | - | - |

| Adgrg4 | - | NS | microarray | adult (human: glomerulus) | - | - |

| Adgrg5 | - | HPA | IHC | adult (human: tubular cells) | - | - |

| Adgrg6 | Formstone et al., 2010; Karner et al., 2015 | EX, HPA, NS | IHC, ISH, RT-PCR, microarray | embryonic (E14.5 mouse: collecting system), adult (human: pelvis, vessels/ mouse: cortical collecting duct/ zebrafish) | - | - |

| Adgrg7 | Formstone et al., 2010 | - | RT-PCR | adult (zebrafish) | - | - |

| Adgrv1 | - | HPA, NS | IHC, microarray | adult (human: medulla) | - | - |

EX, EURExpress; HPA, The Human Protein Atlas; NS, Nephroseq; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISH, in situ hybridization; NB, Northern blot; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; WB, Western blot.

Table 2.

Adhesion GPCRs associated to kidney disease.

| aGPCR member | References | Nephroseq (x-fold) | FireBrowse (x-fold) | NCIGDC | cBio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccRCC | chRCC | pRCC | |||||

| Adgrl1 | - | mDN (1.596) | 0.420 | 1.870 | 0.919 | - | - |

| Adgrl2 | - | IgA (1.734), DN (1.791), LN (2.228) CKD (2.204) | 1.060 | 0.867 | 0.766 | - | - |

| Adgrl3 | - | - | 0.590 | 0.124 | 0.076 | - | - |

| Adgrl4 | Nie et al., 2012 | IgA (2.757), LN (2.493), mDN (1.525) | 2.130 | 0.405 | 0.179 | - | chRCC (11%) |

| Adgre1 | - | DN (1.566), mDN (1.654), mLN (3.238) | 7.740 | 1.95 | 3.210 | - | - |

| Adgre2 | - | V (1.718), LN (1.756) | 5.750 | 1.110 | 2.270 | - | - |

| Adgre3 | - | CKD (5.716) | 1.920 | 0.518 | 2.510 | - | - |

| Adgre4 | - | CKD (6.363) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adgre5 | - | IgA (2.243), DN (2.488), V (2.278) HT (2.132), FSGS (2.121) MCD (1.642), LN (2.264) MG (1.645) | 2.550 | 0.336 | 1.960 | - | - |

| Adgra1 | - | CKD (5.460), mDN (3.564) | 0.081 | 1.390 | 0.138 | - | - |

| Adgra2 | - | APOL1 (1.526) | 2.920 | 0.754 | 0.219 | - | - |

| Adgra3 | - | CKD (2.253), APOL1 (1.905) | 0.857 | 0.476 | 1.840 | - | chRCC (15%) |

| Adgrc1 | - | - | 1.090 | 0.176 | 0.871 | ccRCC (11%) pRCC (10%) | ccRCC (15%) |

| Adgrc2 | - | - | 0.577 | 0.199 | 0.709 | - | - |

| Adgrc3 | - | - | 2.190 | 3.060 | 4.770 | ccRCC (12%) pRCC (10%) | chRCC (15%) |

| Adgrd1 | - | mDN (1.630) | 0.288 | 0.073 | 0.325 | - | - |

| Adgrd2 | - | CKD (2.294) | 1.220 | - | 1.870 | - | - |

| Adgrf1 | - | mDN (2.708), CKD (5.413) | 0.002 | 0.544 | 0.146 | - | - |

| Adgrf2 | - | CKD (6.115) | 0.966 | 0.084 | 2.560 | - | - |

| Adgrf3 | - | - | 0.050 | 0.160 | 0.099 | - | - |

| Adgrf4 | - | CKD (5.402) | 2.150 | 0.118 | 3.310 | - | chRCC (11%) |

| Adgrf5 | Nie et al., 2012 | - | 0.702 | 1.600 | 0.056 | - | - |

| Adgrb1 | Calderón-Zamora et al., 2017; Mathema and Na-Bangchang, 2017 | - | 0.910 | 0.010 | 1.040 | - | chRCC (11%) |

| Adgrb2 | - | CKD (1.786) | 0.424 | 0.355 | 2.110 | - | chRCC (14%) |

| Adgrb3 | - | CKD (3.092) | 0.169 | 0.052 | 0.240 | - | - |

| Adgrg1 | - | FSGS (3.100), CKD (2.189), mDN (2.145) | 0.703 | 3.890 | 0.476 | - | - |

| Adgrg2 | Kudo et al., 2007 | DN (1.701), CKD (4.762), mDN (2.221), mLN (2.832) | 2.340 | 1.180 | 0.413 | - | chRCC (11%) |

| Adgrg3 | Wang et al., 2013 | mDN (2.938) | 2.230 | 3.890 | 1.610 | - | - |

| Adgrg4 | - | CKD (4.004) | 1.160 | 0.539 | 1.490 | - | - |

| Adgrg5 | - | CKD (1.605) | 2.410 | 0.941 | 2.100 | - | - |

| Adgrg6 | - | DN (1.942), CKD (3.872), mLN (1.700) | 1.900 | 0.418 | 2.00 | - | - |

| Adgrg7 | - | CKD (5.656) | 1.990 | 2.080 | 1.970 | - | - |

| Adgrv1 | - | CKD (6.362) | 0.072 | 0.399 | 0.028 | ccRCC (16%) pRCC (19%) | chRCC (11%) |

APOL1, APOL1-associated kidney disease; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; chRCC, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DN, diabetic nephropathy; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; HT, hypertension-injured kidney; IgA, IgA nephropathy; LN, lupus nephritis; MCD, minimal change disease; mDN, mouse model of diabetic nephropathy; MG, membranous glomerulopathy; mLN, mouse Berthier model of lupus nephritis with proteinuria; pRCC, papillary renal cell carcinoma; V, vasculitis-injured kidney; red boxes, <2.5-fold downregulation; green boxes, >2.5-fold upregulation.

aGPCRs in kidney development

Adgrc1 (Celsr1) is required for ureteric bud branching

The best characterized aGPCR in regards to its function during kidney development is Adgrc1 (Celsr1). Yates and co-workers demonstrated in 2010 that Adgrc1 and Vangl2 are required for normal lung branching morphogenesis (Yates et al., 2010b). In the same year they reported furthermore that Vangl2 is required for mammalian kidney-branching morphogenesis (Yates et al., 2010a). In this manuscript they also described Adgrc1 expression in podocytes, proximal tubular cells, collecting duct stalks and S-shaped bodies in the nephrogenic cortex of E18.5 mouse embryos. The study was based on an antibody whose specificity was validated by utilizing loss-of-function Celsr1Crsh/Crsh embryos (Yates et al., 2010b). Yet, the authors did not analyze the role of Adgrc1 during kidney development. Data from the EURExpress database (Diez-Roux et al., 2011), released in 2011, suggest that Adgrc1 is expressed at E14.5 in mice and further indicated that Adgrc1 plays a role in kidney development. Finally, Bróska and co-workers demonstrated in 2016 that Adgrc1 is required, in association with the planar cell polarity gene Vangl2, for ureteric bud branching (Brzoska et al., 2016). Mice carrying mutations in Adgrc1 (Celsr1Crsh/Crsh and Celsr1Crsh/+) or Vangl2 (Vangl2Lp/+) exhibited branching defects in the ureteric tree at E13.5, which were more severe in Celsr1Crsh/+:Vangl2Lp/+ mice. At E17.5 kidneys exhibited overall growth retardation (Celsr1Crsh/+:Vangl2Lp/+ > Celsr1Crsh/Crsh > Celsr1Crsh/+) and histological analysis revealed mitotic spindle misorientation (along the longitudinal axis of the kidney tubules), dilation of cortical tubules in Celsr1Crsh/Crsh mutants and an up-regulation of Gdnf and Ret mRNA levels in the Celsr1Crsh/+:Vangl2Lp/+ mutants. It is noteworthy that cleavage of Adgrc1 at its GPS motif has so far not been reported (Formstone et al., 2010; Hamann et al., 2015). Thus, GPS-based cleavage of Adgrc1 seems not to play a role in kidney development.

During adult renal physiology, Adgrc1 seems not to play a major role as none of the databases indicates its expression in adult renal cells. In adult zebrafish, a low expression of the Adgrc1 homolog adgrc1a (celsr1a) has been described in the kidney compared to the expression level in whole embryos at 10 h post fertilization (hpf) based on quantitative real-time PCR (Harty et al., 2015). However, considering only the expression levels in the investigated adult zebrafish organs (6 months), adgrc1a is markedly enriched in kidney, intestine, and skin compared to brain, eye, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, ovaries and testis (Harty et al., 2015). The only information available in the utilized developmental databases is that ADGRC1 is expressed in renal vessels (HPA database).

aGPCRs strongly correlated to renal development

In this section, we discuss aGPCRs whose correlation to kidney development is strongly supported by data of several databases.

Adgrg6 (Gpr126)

Plays an essential role in neural, cardiac and ear development (Patra et al., 2014) as well as cartilage biology and spinal column development (Karner et al., 2015). The exact role and underlying signaling mechanism is still poorly understood. While no publication described so far the expression of Adgrg6 during kidney development, in situ hybridization data available from the EURExpress database suggest that Adgrg6 is expressed in E14.5 mouse embryos in the outgrowing ureteric bud branches of the metanephros (sections 9–12, 18–21). A possible renal function of Adgrg6 is further supported by its RNA expression in the adult kidney of zebrafish (Harty et al., 2015) and humans (HPA database, vessels). Harty and coworkers revealed that adgrg6 (gpr126) expression in the adult zebrafish kidney is comparable to the maximal expression level observed during development (3 days post fertilization, 3 dpf). adgrg6 was only higher expressed in adult skeletal muscle (around 4 times enriched). Moreover, data from the Nephroseq database confirm the ADGRG6 expression in the human kidney suggesting that it is enriched in the renal pelvis, which arises from the outgrowing ureteric bud branches. Similarly, Pradervand and coworkers published that Adgrg6 is enriched in the cortical portion of the collecting duct in mice compared to the expression in the distal convoluted tubule and the connecting tubule based on microarray-based gene expression profiles (Pradervand et al., 2010). Collectively, the available data for Adgrg6 suggest that it is expressed during kidney development as well as adulthood, being enriched in collecting duct cells. However, the described data are all RNA-based data as currently no reliable protein expression data are available. Moreover, no kidney phenotype has so far been described in Adgrg6 knockout mice, neither in the lines that are embryonic lethal at E11.5 (Patra et al., 2013) nor in Taconic knockouts of which some are born alive (Monk et al., 2011). Currently, we are utilizing our model systems (Patra et al., 2013) including conditional mouse lines (Mogha et al., 2013) to determine if the role of Adgrg6 might be underestimated in kidney development.

Adgre5 (CD97)

Is an activation-associated leukocyte antigen suggested to act as an adhesion molecule (Hamann et al., 2000). The association of Adgre5 with the decay accelerating factor (DAF) prevents cells from complement-mediated attack and therefore it is of great importance in the study of autoimmunity and graft rejection (Toomey et al., 2014). Already in 1999 first evidence, based on Northern blot analysis, was provided that Adgre5 is expressed in the adult mouse kidney (Qian et al., 1999). A possible role of Adgre5 in adult kidney physiology was further supported by the detection of Adgre5 RNA in adult porcine kidney (de la Lastra et al., 2003), strong expression in adult zebrafish kidney [homolog adgre5a (cd97a)] (Harty et al., 2015), and more importantly by the detection of Adgre5 protein in intraglomerular mesangial cells of the adult mouse kidney (Jaspars et al., 2001) utilizing validated monoclonal antibodies (Hamann et al., 1996). In 2008, the analysis of a LacZ knockin reporter mouse line in combination with desmin expression analysis demonstrated that Adgre5 is expressed in podocytes and mesangial cells of 4 months-old mice (Veninga et al., 2008). This is in agreement with data from the Nephroseq database that indicates that ADGRE5 is enriched in the adult human glomerulus and renal pelvis. Yet, also despite a strong expression signal for Adgre5 in the collecting duct system of E14.5 mouse embryos (EURExpress, sections 9–11, 18–21), 4 months-old Adgre5 knockout mice showed no overt phenotype in the analyzed organs, including the kidney.

Subfamily VI

First evidence for a role of these family members during kidney physiology was provided by Abe and coworkers in 1999. They demonstrated by Northern blot analysis that Adgrf5 (Gpr116/Ig-Hepta) is at low levels expressed in the adult rat kidney and identified by immunohistochemistry intercalated cells of the cortical collecting duct as the origin of expression (Abe et al., 1999). Previously, it has been demonstrated that it has a well-established role in lung surfactant homeostasis and that its deletion results in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance as well as a subtle vascular phenotype (Nie et al., 2012; Bridges et al., 2013; Fukuzawa et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Niaudet et al., 2015). According to the Nephroseq database, ADGRF5 is also expressed in the adult human kidney. Recently, transgenic mice expressing mCherry under the control of the Adgrf5 promoter (Gpr116-mCherry) as well as knockout mice were generated (Lu et al., 2017). The analysis of 8 weeks-old reporter mice revealed that Adgrf5 is expressed in endothelial cells of the microvessels in different organs. In the kidney, Adgrf5 expression was also detected in microvessels and in glomeruli exclusively in endothelial cells and not in mesangial cells or podocytes. The previously described expression in intercalated cells of the cortical collecting duct was not confirmed. While Adgrf5 knockout mice exhibited no obvious renal phenotype, Adgrf5/Adgrl4 (Eltd1) double knockout mice exhibited a hemolysis phenotype (Lu et al., 2017). In addition, these mice exhibited proteinuria as well as uremia indicating kidney failure. This was correlated to increased mesangial matrix and a damaged glomerular filtration barrier including loss of endothelial fenestration and fusion of podocytes foot processes. Minor albuminuria was already detected at birth. The authors concluded that Adgrf5/Adgrl4 double knockout mice exhibit glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy. Note, Adgrl4 knockout mice exhibited no obvious kidney phenotype. Moreover, endothelial-specific deletion of Adgrf5/Adgrl4 utilizing VE-Cad-Cre mice, which are known to induce recombination in the endothelium of arteries and capillaries of the glomerulus of adult kidneys (Alva et al., 2006), resulted in no renal phenotype.

Prömel and coworkers investigated in 2012 by RT-PCR the expression of most members of subfamily VI [Adgrf1 (Gpr110), Adgrf2 (Gpr111), Adgrf4 (Gpr115), and Adgrf5]. They observed based on this analysis that Adgrf1 is strongly expressed in the adult mouse kidney (Prömel et al., 2012), confirming previous data by Lum and coworkers demonstrating ADGRF1 expression in the adult human kidney (Lum et al., 2010). In addition they detected very weak expression levels of Adgrf4 (abundantly expressed in the skin) and Adgrf5 (most abundantly expressed in lung, liver, and heart). No or at best faint expression was detected for Adgrf2. Subsequently, they generated reporter mouse lines and knockout mice for loss-of-function studies for Adgrf1, Adgrf2, and Adgrf4. The analysis of these mouse lines revealed strong expression of Adgrf1 in the adult renal pelvis and ureter. For Adgrf2 and Adgrf4 no conclusive data were provided. Despite some indications of renal expression, the authors detected in none of the generated knockout mouse lines an obvious renal phenotype. According to the Nephroseq database, ADGRF1 is enriched in the papillary tips, ADGRF3 (GPR113) in the glomerulus, and ADGRF5 in all renal structures, except for the pelvis, of the adult human kidney.

aGPCRs weakly correlated to renal development

In this section, we discuss aGPCRs for which data are available but not sufficient, or even contradictory, to draw a strong conclusion in regards to a kidney-specific function.

Subfamily I

Like Adgrf5, Adgrl4 is expressed in endothelial cells (Lu et al., 2017). Initially, it was described as a receptor upregulated in the adult heart (Nechiporuk et al., 2001). Subsequently, it has been shown to counteract pressure overload-induced myocardial hypertrophy (Xiao et al., 2012) and to regulate tumor angiogenesis (Masiero et al., 2013). During early mouse development, Adgrl4 is detected in the heart endocardium, different regions of the brain and in the developing metanephros of E14.5 mice, according to EURExpress (sections 5–8, 14–17). The analysis of reporter mice revealed, similarly to Adgrf5, that Adgrl4 is expressed in the adult microvasculature and in the kidney exclusively in endothelial cells and not in mesangial cells or podocytes of the glomeruli. In contrast to Adgrl4, little information is available for the other subfamily members. Based on Northern blot analysis it has been suggested that ADGRL1 (LPHN1) (Sugita et al., 1998) and ADGRL2 (LPHN2) (Sugita et al., 1998; Ichtchenko et al., 1999) are expressed in the adult human kidney. Analysis of RNA from adult rat kidneys suggests at best a very low level of expression of Adgrl1 (compared to brain) and Adgrl2 (compared to brain, lung and liver) (Matsushita et al., 1999).

Adgrg1 (Gpr56)

According to the analyzed databases, Adgrg1 is low expressed in E12.5 mouse ureteric branches (EURExpress, sections 10–13 and 19–22 of the template T60042 in sagittal section) and enriched in the renal cortex of human adult kidneys (Nephroseq). The expression of ADGRG1 in the adult human kidney has further been supported by published Northern blot (Shashidhar et al., 2005) and western blot data (Huang et al., 2008). Yet, no renal phenotype has been described so far for Adgrg1 knockout mice (Huang et al., 2008).

Adgra2 (Gpr124)

Recently, Calderon-Zamora and co-workers have described that Adgra2 is expressed on mRNA level (RT-PCR) in the adult kidney of normotensive and hypertensive rats (Calderón-Zamora et al., 2017). A possible role of Adgra2 during kidney development and adult renal physiology is further supported by data from the databases EURExpress (sections 8–10, 16–18) and Nephroseq (enriched in adult renal pelvis).

Adgrb1 (Bai1)

Izutsu and coworkers demonstrated by quantitative RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry that ADGRB1 is expressed on mRNA and protein level in the kidney with prominent expression in proximal and distal tubules (Izutsu et al., 2011).

The databases EURExpress and Nephroseq also suggest a possible role for Adgrc2 (Celsr2) in kidney development and physiology (widely expressed, sections 5, 7–10, 17–19; enriched in human adult medulla). In addition, the databases EURExpress and HPA suggest a possible role for Adgra3 (Gpr125) (nephrogenic cortex, sections 6–10, 17, 19, 20; low protein expression in adult human tubules).

The Nephroseq database further suggests that ADGRE1 (EMR1), ADGRB3 (BAI3), and ADGRG4 (GPR112) are enriched in the glomerulus, ADGRB2 (BAI2) in the renal pelvis, and ADGRV1 (GPR98) in the medulla of the adult human kidney. The HPA database indicates that ADGRG5 (GPR114) is expressed at low levels in tubules.

Finally, the analysis of aGPCRs during zebrafish development suggests that also adgra1l (gpr123l) (most abundant in kidney and skeletal muscle), adgrg3 (gpr97) (strongly expressed during adulthood in most organs), and adgrg7b (gpr128b) (markedly higher expressed in the adult kidney than in any other adult organ or at any other developmental stage) are expressed in the adult zebrafish kidney.

Conclusion I

Our analysis of publicly available data revealed that the role of aGPCRs during kidney development and physiology is poorly characterized. Yet, a plethora of descriptive data indicates that a large number of aGPCRs are expressed in the kidney from zebrafish to humans in a variety of cell-type specific expression patterns. As most of the available data are based on RNA or “Omics” approaches and as limited information is provided on temporal expression patterns, it is important to validate expression on protein level and to perform detailed spatio-temporal expression analyses. Furthermore, it is fundamental to characterize in detail the available knockout mouse lines for renal phenotypes. Hereby, it should be considered that aGPCRs might have overlapping functions and thus, due to the high number of expressed aGPCR members in the kidney, it might be necessary to utilize double knockout mice (e.g., Adgrf5/Adgrl4) to elucidate the function of aGPCRs during kidney development and physiology.

Kidney disease and cancer

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents the fastest growing pathology worldwide (Kam Tao Li et al., 2013) with an increase of over 90% from 1990 to 2010 (Lozano et al., 2012). The prevalence of CKD is in many countries >10% (Ortiz et al., 2014; Mills et al., 2015). Independent of the original cause of impaired renal function (e.g., diabetes mellitus, 30–40%; hypertension, 20%; inflammation of the glomeruli (glomerulonephritis), 13%; interstitial nephritis, 10%; polycystic kidney disease, 6%) the common final outcome of almost all progressive CKDs is renal fibrosis (Liu, 2011; Humphreys, 2017). CKDs represent an important risk factor for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases and progress toward end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (Eckardt et al., 2013; Balogun et al., 2017), which can only be treated by renal replacement therapies (RRT) like hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or transplantation (Eckardt et al., 2013). Yet, despite improvements in immunosuppressive medications and renal allograft survival, there is an increasing shortage of available donor kidneys. For example, from 2003 to 2013, the number of patients waiting for a kidney transplant has doubled in the United States. This is mainly due to the fact that diabetes, historically the most common cause of ESRD, is now the fastest rising cause of ESRD (McCullough et al., 2009; Matas et al., 2015). The standard therapy of CKD is antiproteinuric treatment mostly by blockade of the renin-angiotensin system and the management of blood pressure as well as blood glucose levels. This therapeutic regimen slows the progression of the disease, but it cannot reverse or functionally repair the damage, or at least stop progression. In addition, the effect of this regimen depends significantly on the stage of CKDs. In recent years, therefore, new strategies have been proposed for the treatment of CKD that focus on several factors that have been linked to the progression of kidney disease. The main focus is on drugs that have anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects. At present, these drugs are being tested with the aim of preserving kidney function (Pena-Polanco and Fried, 2016).

Besides CKD, kidney cancer represents a significant socio-economic challenge. Every year around 64,000 patients in the United States and approximately 115,000 patients in Europe are diagnosed with kidney cancer representing 5% of all new diagnosed cancers. In addition, kidney cancer causes yearly in the United States and in Europe nearly 15,000 and 49,000 deaths, respectively (Siegel et al., 2017). The most common kidney tumor is the renal cell carcinoma (RCC) comprising 80% to 90% of all malignant kidney tumors and 70–80% of all solid renal tumors (Ljungberg et al., 2011; Ridge et al., 2014). It originates from the epithelial tubular cells. RCC is characterized by an asymptomatic disease course and thus is often diagnosed late explaining the high mortality rates. It needs to be noted that during the last years it has been recognized that renal cell tumors are more heterogeneous on a histologically and molecularly level than thought. Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of renal cell tumors has just recently been modified (Inamura, 2017). The major current subtypes are clear cell RCC (ccRCC, proximal tubule origin), papillary RCC (pRCC, proximal tubule origin), and chromophobe RCC (chRCC, collecting duct origin). ccRCC is a hypervascularized (fragile thin-walled, staghorn-shaped vasculature). Possible causes of ccRCC are mutations in the VHL gene (90%) as well as genetic aberrations of mTOR pathway proteins (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017). Type 1 pRCC is characterized by MET proto-oncogene-activating mutations and type 2 with activation of the NRF2/antioxidant response element pathway due to the increased oxidative stress. In contrast to ccRCC, pRCC is characterized as hypovascularized region compared to the adjacent parenchyma (Herts et al., 2002). chRCC is a rare cancer and the least aggressive of all RCC subtypes. It is characterized unlike ccRCC by thick-walled blood vessels (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017). Finally, ccRCC shows a less favorable outcome compared with pRCC and chRCC and has a greater propensity to metastasize (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017).

Complete surgical tumor resection (radical or partial nephrectomies) remains the standard of care for all localized RCCs. Resection of smaller solitary tumors offers a cure for most patients (Autorino et al., 2017). However, this procedure often results in nephron loss as well as a decreased glomerular filtration rate in CKD stage 3 or higher associated with cardiovascular complications, including death (Weight et al., 2010). In the case of unresectable or metastatic RCC, a systemic immunotherapy (IL-2, severe toxicity) or systemic treatment with antiangiogenic factors (frequently leads to hypertension and proteinuria) or mTOR inhibitors is required (Sánchez-Gastaldo et al., 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017). It should be noted that a large variety of cancers as well as different cancer therapies cause by themselves acute kidney injury and/or CKD through several mechanisms (Małyszko et al., 2017).

Collectively, kidney diseases including kidney cancer represent a major socio-economic burden for which no effective therapy is available. This illustrates the importance to identify early markers of RCC and to better understand on a molecular basis CKD as well as the regenerative potential of the kidney to elucidate new therapeutic targets to delay late stage CKD progression, to stop CKD progression or in the best case to reverse kidney injury.

Relevance of aGPCRs in cancer

The GPCR superfamily is currently responsible for the therapeutic effect of 33% of all drugs approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Santos et al., 2017). Thus, GPCRs represent the most successful class of pharmaceutical targets. While only a handful of GPCRs have been demonstrated to be oncology drugs, GPCRs play key roles in cancer and thus pharmacological modulation of GPCR function has great potential for the development of novel anti-cancer therapeutics (Nieto Gutierrez and McDonald, 2017). Notably, there is also published evidence for the role of aGPCRs in cancer suggesting them as attractive drug targets. For example, increased expression levels of ADGRG1, ADGRE5, and ADGRF5 has been detected in a variety of human cancers such as glioma (ADGRG1) (Shashidhar et al., 2005), gastric (Liu et al., 2005), pancreatic (He et al., 2015), esophageal (Aust et al., 2002), prostate (Ward et al., 2011), colorectal carcinomas (Steinert et al., 2002) (ADGRE5), and breast cancer (ADGRF5) (Tang et al., 2013). Moreover, their importance in tumorigenesis has been substantiated in xenograft tumor models. ADGRG1 knockdown resulted in melanoma growth inhibition and regression (Ke et al., 2007), while knockdown of the other 2 aGPCRs reduced lung (ADGRF5) (Tang et al., 2013) and/or bone metastasis (ADGRE5, ADGRF5) (Ward et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2013). Detailed in vitro and in vivo analyses further indicated that ADGRG1 is a prosurvival factor in cancer cells and promotes anchorage-independent growth (Ke et al., 2007) whereas ADGRE5 (Ward et al., 2011) and ADGRF5 (Tang et al., 2013) regulate RhoA-dependent cell migration and invasion.

Relevance of aGPCRs in kidney disease including kidney cancer

Literature-based evidence supported by database information

As detailed below, our literature search identified publications describing five aGPCRs correlated with kidney disease including renal cancer: Adgrb1, Adgrg2 (Gpr64), Adgrl4, Adgrg3, and Adgrf5.

Adgrb1 suppresses RCC angiogenesis

It is well known that new vascular formation (angiogenesis) is required for tumor growth, invasion and metastasis (Carmeliet and Jain, 2000). This process is directly promoted by VEGF (Carmeliet, 2005). Yet, there are also a large variety of other factors that control tumor angiogenesis including Adgrb1 (Mathema and Na-Bangchang, 2017). Izutsu and coworkers demonstrated by quantitative RT-PCR a 4-fold decrease in ADGRB1 expression in RCC tissue compared to normal kidney tissue, whereby ADGRB1 mRNA and protein expression were lower in advanced RCC than in localized RCC tissues. Moreover, the authors identified a negative correlation between microvessel density and ADGRB1 protein expression. VEGF expression was not affected (Izutsu et al., 2011). These data suggested that downregulation of ADGRB1 during RCC contributes to an improved tumor angiogenesis and thus enhanced tumor growth. This is in agreement with the previous findings of Kudo and coworkers who studied the potential of ADGRB1 as an anti-angiogenic factor in RCC based on the known inverse correlation of its expression with vascular density in other tumor types (Kudo et al., 2007). They demonstrated in an in vivo tumor model (subcutaneous inoculation of the RCC cell line Renca) that ADGRB1 overexpression in Renca reduced tumor growth due to reduced microvessel density which was associated with reduced VEGF expression levels (Kudo et al., 2007). The role of ADGRB1 is further supported by the FireBrowse database which indicates that ADGRB1 is downregulated in chRCC (0.010-fold, Table 2) and the cBio database indicating a mutation rate of 11% in chRCC. The observed downregulation of ADGRB1 in chRCC might be an explanation for an increased vascularization associated with chRCC (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017) and is consistent with no change in hypovascularized pRCC (Herts et al., 2002). The lack of downregulation in hypervascularized ccRCC might be due to the different types of vessels (fragile vs. thick-walled; Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017).

Adgrg2 is involved in tumor invasiveness

ADGRG2 is highly expressed in several human cancer cell lines including 8 human RCC cell lines: CAKI-1, 786-0, A498, ACHN, SN12-C, (all ccRCC), TK-10, RXF 393, and UO-31 (Richter et al., 2013). In addition, it is overexpressed in Ewing's sarcoma cell lines (Richter et al., 2013). Ewing's sarcoma is an aggressive, small round-cell tumor with a strong potential to metastasize. Typically it arises from the trunk and long bones of children or young adults (Toomey et al., 2010). Yet, it can also primarily occur in soft tissues, like the kidney (extra-skeletal Ewing's sarcomas), whereby its cellular origin is still unknown (Faizan et al., 2014). Richter and coworkers demonstrated that inhibition of Adgrg2 expression impaired colony formation in vitro (A673, SB-KMS-KS1 and TC-71) and suppressed local tumor growth and metastasis in an immunodeficient mouse xenograft model of human cancer [SB-KMS-KS1/Rag2(−/−)γC(−/−)]. Finally, the authors present evidence that Adgrg2 regulates invasiveness and metastatic spread via induction of placental growth factor (PGF) and matrix metalloproteinase 1 (Mmp-1) expression (Richter et al., 2013). Consequently, the FireBrowse database shows that ADGRG2 is only upregulated in ccRCC (2.34, Table 2), the most metastatic RCC subtype (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017).

In addition, Nephroseq data suggest that ADGRG2 is upregulated in diabetic nephropathy (human, mouse model), CKD (human) as well as in the mouse Berthier model of lupus nephritis with proteinuria. This finding is in agreement with the fact that these diseases as well as RCC are associated with abnormal expression levels of MMPs (Nakamura et al., 2000; Catania et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2010), including MMP-1 (Nakamura et al., 1993, 2000; Bhuvarahamurthy et al., 2006) which is known to be regulated by Adgrg2 (Richter et al., 2013). In addition, it has been demonstrated that, despite the large number of MMPs known to be expressed in the healthy kidney (Catania et al., 2007), changes in a single MMP can cause kidney disease (Cheng et al., 2006). Moreover, it has been shown that diabetes and systemic lupus erythematosus can cause CKD through excessive levels of blood glucose or deposition of immune complexes, respectively, resulting in defects in the basement membrane, podocyte effacement, increase in mesangial cell number and extracellular matrix (Fibbe and Rabelink, 2017; Sharaf El Din et al., 2017). Ultimately, these conditions lead to scarring and stiffening of the glomerulus (glomerulosclerosis), tubulointerstitial fibrosis and CKD (Meguid El Nahas and Bello, 2005).

Adgrl4 correlates with better prognosis in ccRCC

As described above in the section about kidney development, Adgrf5/Adgrl4 double knockout mice exhibit significantly reduced kidney function. Around half of the double-deficient mice died perinatally, while the other half showed growth impairment and all died within 3 weeks to 3 months postnatally. The analysis of 7 weeks-old mice revealed massive proteinuria and uremia. Analyses of 4 weeks-old mice revealed a set of pathological features indicating glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy: schistocytes in the subendothelial zone of the glomerular capillaries, loss of endothelial fenestration and fusion of podocytes foot processes (Lu et al., 2017). Notably, even though Adgrl4 and Adgrf5 are highly expressed in endothelial cells, endothelial-specific deletion of Adgrf5/Adgrl4 utilizing VE-Cad-Cre mice resulted in no renal phenotype. This suggests that at least one of these aGPCRs might have a function in a renal cell type.

A possible role of ADGRL4 in renal cancer has been proposed by Masiero and collaborators. They analyzed the expression profile of 1,080 primary human cancer samples including 170 ccRCC samples (Masiero et al., 2013). Utilizing a validated anti-ADRGL4 antibody they detected ADGRL4 expression in the endothelial cells and pericytes of all investigated normal and pathological tissues. In ccRCC samples, ADGRL4 expression was significantly higher than in the healthy control and its expression level correlated positively with ccRCC microvessel density. Importantly, the authors demonstrated that ADGRL4 is required for proper endothelial sprouting and vessel formation in vitro and in vivo and that its inhibition drastically reduced tumor growth improving survival (Masiero et al., 2013). FireBrowse data confirm this observation indicating an upregulation (2.13-fold, Table 2) only in the hypervascularized ccRCC subtype (Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017). It should be noted that ADGRL4 is downregulated (0.179-fold) and mutated (11%) in chRCC (Table 2), which might be explained, similarly as for ADGRB1, by the different types of vessels (fragile vs. thick-walled; Low et al., 2016; Inamura, 2017; Shingarev and Jaimes, 2017).

Besides a role in kidney, ADGRL4 upregulation is according to the Neprhoseq database associated with IgA nephropathy (33 human samples, 2.757 fold change, p = 5.18E-12) as well as lupus nephritis (46 human samples, 5.493 fold change, p = 2.46E-7). In addition, it has been associated with diabetic nephropathy in mice (39 samples, 1.525 fold change, p = 0.002) but not in humans (22 samples,−2.116 fold change, p = 0.999). Diabetic nephropathy, IgA nephropathy and lupus nephritis are all glomerular diseases in which sclerosis, increases in the mesangial matrix and hypercellularity of the mesangial cells are common pathological features (Meguid El Nahas and Bello, 2005; Fibbe and Rabelink, 2017; Sharaf El Din et al., 2017). Yet, while Adgrl4 is clearly associated to endothelial cells and the microvasculature, there appears no common phenotype in regards to an increased microvascular density (as in hypervascularized ccRCC). This suggests, similar as the lack of a renal phenotype in conditional Adgrf5/Adgrl4 x VE-Cad-Cre mice (see above), that Adgrl4 has a so far unknown function in a non-endothelial type. It should be once more noted that according to EURExpress (sections 5–8, 14–17) Adgrl4 is detected in the developing metanephros of E14.5 mice. Yet, based on these data it is difficult to determine if Adgrl4 is expressed in cells other than the endothelial cells of the microvasculature.

Adgrg3 and its relation with diabetic nephropathy

Adgrg3 is highly expressed in immune cells, but its function remains largely unknown (Peng et al., 2011). Consistent with the fact that the kidney develops macrophage-associated local inflammation in response to metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance and diabetes (Navarro-González and Mora-Fernandez, 2008; Declèves and Sharma, 2015), Adgrg3 is according to the Nephroseq database upregulated in the mouse model of diabetic nephropathy (12 samples, 2.938 fold change, p = 2.55E-6). Loss of function experiments revealed that Adgrg3 has a crucial role in maintaining normal splenic architecture and regulating B cell development (Wang et al., 2013). Notably, Shi and coworkers reported recently that more (2-fold) macrophages invaded the kidney of Adgrg3 knockout mice on high-fat diet (HFD) compared to HFD wildtype mice (Shi et al., 2016). This phenotype was correlated to higher expression levels of the inflammatory factor TNF-α. Yet, major metabolic phenotyping showed no difference between Adgrg3 knockout and wildtype mice on HFD.

In RCCs, ADGRG3 is according to the FireBrowse database upregulated in all three RCC subtype with the highest expression in chRCC (3.89-fold, Table 2). This is consistent with the fact that immune cells and inflammatory processes significantly contribute to RCC development and disease progression (de Vivar Chevez et al., 2014).

Additional database information

Overall, the data obtained from the utilized databases indicate that almost all aGPCRs are associated to kidney diseases including APOL1-associated kidney disease, ccRCC, chRCC, CKD, diabetic nephropathy, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), hypertension-injured kidney, IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, minimal change disease, membranous glomerulopathy, pRCC, and vasculitis-injured kidney. Below we discuss the diseases to which expression changes of several aGPCRs have been associated.

CKD

Long-term kidney damage independent of its origin progressively leads to a chronic disease state characterized by an irreversibly low glomerular filtration rate (Meguid El Nahas and Bello, 2005). According to the Nephroseq database, 18 out of 33 human aGPCRs are upregulated in CKD compared with healthy counterparts. Additionally, in two thirds of the cases (12 out of 18), the fold change increase is >3. The altered expression of that many aGPCRs is most likely a reflection of the large variety of etiologies underlying CKD and the multiple common pathophysiological processes involved such as inflammation, ischemia, hypoxia, fibrosis, and metabolic waste accumulation.

Lupus nephritis, diabetic nephropathy, IgA nephropathy

These are the kidney diseases that are associated with upregulation of a larger number of aGPCRs. Moreover, they exhibit similar aGPCR signatures which might reflect that all these diseases are glomerular diseases sharing common pathological features such sclerosis, increases in the mesangial matrix and hypercellularity of the mesangial cells (Meguid El Nahas and Bello, 2005; Fibbe and Rabelink, 2017; Sharaf El Din et al., 2017). Increased expression levels were found for ADGRL2, ADGRL4, ADGRE1, ADGRE5, ADGRG2, and ADGRG6 in lupus nephritis and diabetic nephropathy, whereby ADGRL2, ADGRL4 and ADGRE5 were also upregulated in IgA nephropathy (Table 2). As described above, altered expression of Adgrg2 reflects the involvement of MMPs in these diseases (Nakamura et al., 1993, 2000; Bhuvarahamurthy et al., 2006; Catania et al., 2007; Jiang et al., 2010; Richter et al., 2013). Altered expression of ADGRE1 and ADGRE5 is most likely due to inflammatory processes underlying the progression of the three diseases (Galkina and Ley, 2006; Imig and Ryan, 2013). Adgre1 is in mice a macrophage marker (Lin et al., 2010) and in humans a marker of eosinophilic granulocytes (Hamann et al., 2007). Adgre5 is widely expressed along the lymphoid and myeloid lineages (Hamann et al., 2015). Consequently, Adgre5 is upregulated in autoimmune diseases (Wandel et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017). In contrast, the role of ADGRL4 in these diseases remains unclear as discussed above. In regards to ADGRL2 and ADGRG6 no published information is available that would allow to conclude what role they might play. Adgrl2 has previously been associated with EMT in chicken valve heart development (Doyle et al., 2006) and Adgrg6 with heart trabeculation and myelination (Patra et al., 2014).

RCCs

According to the here analyzed databases aGPCRs which are related to vascularization (Adgre1, Adgre5, Adgra2) (Wang et al., 2005; Cullen et al., 2011; Wandel et al., 2012) or inflammatory processes (Adgre1, Adgre2, Adgre5) (Gray et al., 1996; Taylor et al., 2005; Hamann et al., 2007; Kuan-Yu et al., 2017) are >2.5-fold upregulated in ccRCC (Table 2). This reflects the high degree of vascularization of ccRCCs (Prasad et al., 2006) and the role of inflammatory related gene expression in its progression (Tan et al., 2011). A role of these genes in vascular and/or inflammation-mediated kidney diseases is further substantiated by the associations with diabetes nephritis (ADGRE1, ADGRE5), lupus nephritis (ADGRE1, ADGRE2, ADGRE5), renal vasculitis (ADGRE2, ADGRE5), IgA nephropathy (ADGRE5) and renal hypertension (ADGRE5). Furthermore, the hypoxia associated aGPCRs ADGRB3 (Kee et al., 2004) and ADGRD1 (Bayin et al., 2016) were >2.5-fold downregulated. In addition, the aGPCRs ADGRA1, ADGRF1, ADGRF3, and ADGRV1 were downregulated for which currently no role can be hypothesized.

In contrast to ccRCC, for chRCC it has been found that the majority of affected aGPCRs (>2.5-fold change) are downregulated (12 out of 15, Table 2). The major known differences between ccRCC and chRCC ist that chRCC is less metastatic, less vascularized and exhibits instead of fragile vessels more thick-walled vessels. Consequently, proangiogenic aGPCRs were not upregulated. In addition, expression of ADGRG1, which promotes cell adhesion (Hamann et al., 2015), is strongly upregulated and might explain the lower metastatic character of chRCC. Yet, the pro-migratory aGPCR ADGRG3 is highly expressed. Collectively, it appears impossible to extrapolate the role of the affected aGPCRs in chRCC without more detailed studies. The same is true for pRCCs, in which 10 aGPCRs were >2.5-fold down- and 5 aGPCRs upregulated. Consistent with its hypoplastic characteristic, the proangiogenic ADGRL4 was downregulated. Yet, the pro-angiogenic factors ADGRE1 and ADGRE5 were upregulated. Note, the FireBrowse data have to be dealt with carefully as no p-values are provided.

Overall, it is apparent that in RCCs the majority of aGPCRs is downregulated (28 out of 40), which is in agreement with the described cellular functions of aGPCRs, which for example mediate cell adhesion and directed cell division (Hamann et al., 2015); processes often misregulated in RCCs. Among the upregulated a GPCRs are consequently aGPCRs that promote angiogenesis (ADGRE1, ADGRE5, ADGRA2) and inflammation (ADGRE1, ADGRE2, ADGRE5) or act in contrast to most other aGPCRs as anti-adhesive molecules (ADGRG1). It has for example been shown that ADGRG1 activation promotes melanoma cell migration (Chiang et al., 2017) and is required for proper β-cell proliferation (Dunér et al., 2016). Yet, it is noteworthy that the cellular functions of aGPCRs are still poorly characterized and thus the kidney might provide a chance to better understand the distinct roles of aGPCRs.

Conclusion II

Our analysis of publicly available data revealed that the role of aGPCRs is also poorly characterized in kidney disease including cancer. However, while the data in the literature is sparse and not always in agreement with available “Omics” data, the publicly available data support the conclusion that aGPCRs are involved in the pathogenesis of a variety kidney diseases. Yet, it needs to be clarified if the majority of the listed associations are due to alterations in vascularization or inflammation of the diseased kidney or if aGPCRs play additional underappreciated kidney-specific roles.

Future directions

Our analysis indicates that a large number of aGPCRs is associated to kidney development and a variety of kidney diseases suggesting an underappreciated role of aGPCRs in kidney development, physiology and pathophysiology. Due to the limited spatio-temporal expression data for aGPCRs in the kidney it is difficult to conclude if certain aGPCRs are de novo expressed during a disease or whether it is a question of reactivation, for example in the context of a fetal gene program. Thus, it is important to generate adequate tools (e.g., validated antibodies and reporter lines) to better characterize the expression patterns of aGPCRs. Considering that multiple single aGPCR knockout mouse lines exhibit no obvious phenotype, further analysis might provide information regarding complementary aGPCRs with compensatory functions. However, it should also be considered that the lack of phenotypes might be due to the lack of a vigorous investigation (e.g., kidney not analyzed, kidney function not challenged) or to an incomplete gene deletion. For example it has been shown that the N-terminal and C-terminal fragment of aGPCRs can have independent functions (Patra et al., 2013). In addition, genetic manipulations of an aGPCR might not affect alternative splice forms (Bjarnadóttir et al., 2007) or induce expression of artificial alternative splice forms. Cell-type specific expression analysis will also help to determine if aGPCRs have a primary role or whether their association is rather due to bystander effects. This, however, appears rather unlikely as aGPCRs regulate a variety of cellular processes known to be essential to kidney development, physiology and pathophysiology. Collectively, it is important that experts in kidney development and disease collaborate with experts in the field of aGPCRs to elucidate the role of aGPCRs in kidney development, physiology and pathophysiology in order to determine if this knowledge can be utilized for better diagnosis and/ or treatment of kidney diseases including RCCs.

Author contributions

SC-V and FE performed literature as well as database review and analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kerstin Amann, Christoph Daniel and the members of the Engel laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. FE acknowledges support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR2149, Project 7, EN 453/10-1 and EN 453/10-2) and the Emerging Fields Initiative [EFI, “CYDER: Cell Cycle in Disease and Regeneration,” Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU)].

References

- Abe J., Suzuki H., Notoya M., Yamamoto T., Hirose S. (1999). Ig-hepta, a novel member of the G protein-coupled hepta-helical receptor (GPCR) family that has immunoglobulin-like repeats in a long N-terminal extracellular domain and defines a new subfamily of GPCRs. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19957–19964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alva J. A., Zovein A. C., Monvoisin A., Murphy T., Salazar A., Harvey N. L., et al. (2006). VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev. Dyn. 235, 759–767. 10.1002/dvdy.20643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aust G., Steinert M., Schutz A., Boltze C., Wahlbuhl M., Hamann J., et al. (2002). CD97, but not its closely related EGF-TM7 family member EMR2, is expressed on gastric, pancreatic, and esophageal carcinomas. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 118, 699–707. 10.1309/A6AB-VF3F-7M88-C0EJ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aust G., Zhu D., Van Meir E. G., Xu L. (2016). Adhesion GPCRs in Tumorigenesis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 234, 369–396. 10.1007/978-3-319-41523-9_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autorino R., Porpiglia F., Dasgupta P., Rassweiler J., Catto J. W., Hampton L. J., et al. (2017). Precision surgery and genitourinary cancers. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 43, 893–908. 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogun S. A., Balogun R., Philbrick J., Abdel-Rahman E. (2017). Quality of life, perceptions, and health satisfaction of older adults with end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 65, 777–785. 10.1111/jgs.14659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayin N. S., Frenster J. D., Kane J. R., Rubenstein J., Modrek A. S., Baitalmal R., et al. (2016). GPR133 (ADGRD1), an adhesion G-protein-coupled receptor, is necessary for glioblastoma growth. Oncogenesis 5:e263. 10.1038/oncsis.2016.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvarahamurthy V., Kristiansen G. O., Johannsen M., Loening S. A., Schnorr D., Jung K., et al. (2006). In situ gene expression and localization of metalloproteinases MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP9, and their inhibitors TIMP1 and TIMP2 in human renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 15, 1379–1384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadóttir T. K., Geirardsdóttir K., Ingemansson M., Mirza M. A., Fredriksson R., Schiöth H. B. (2007). Identification of novel splice variants of Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors. Gene 387, 38–48. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J. P., Ludwig M. G., Mueller M., Kinzel B., Sato A., Xu Y., et al. (2013). Orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR116 regulates pulmonary surfactant pool size. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 49, 348–357. 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0439OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill E. W., Aronow B. J., Georgas K., Rumballe B., Valerius M. T., Aronow J., et al. (2008). Atlas of gene expression in the developing kidney at microanatomic resolution. Dev. Cell 15, 781–791. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzóska H. Ł., d'Esposito A. M., Kolatsi-Joannou M., Patel V., Igarashi P., Lei Y., et al. (2016). Planar cell polarity genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are necessary for kidney growth, differentiation, and rostrocaudal patterning. Kidney Int. 90, 1274–1284. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral P. D., Garvin J. L. (2014). TRPV4 activation mediates flow-induced nitric oxide production in the rat thick ascending limb. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 307, F666–F672. 10.1152/ajprenal.00619.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Fedeles S. V., Dong K., Anyatonwu G., Onoe T., Mitobe M., et al. (2014). Altered trafficking and stability of polycystins underlie polycystic kidney disease. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 5129–5144. 10.1172/JCI67273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Zamora L., Ruiz-Hernandez A., Romero-Nava R., León-Sicairos N., Canizalez-Román A., Hong E., et al. (2017). Possible involvement of orphan receptors GPR88 and GPR124 in the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 39, 513–519. 10.1080/10641963.2016.1273949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. (2005). VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology 69(Suppl. 3), 4–10. 10.1159/000088478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P., Jain R. K. (2000). Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407, 249–257. 10.1038/35025220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll T. J., Park J. S., Hayashi S., Majumdar A., McMahon A. P. (2005). Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev. Cell 9, 283–292. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania J. M., Chen G., Parrish A. R. (2007). Role of matrix metalloproteinases in renal pathophysiologies. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 292, F905–F911. 10.1152/ajprenal.00421.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B. E., Sumer S. O., Aksoy B. A., et al. (2012). The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Pollock A. S., Mahimkar R., Olson J. L., Lovett D. H. (2006). Matrix metalloproteinase 2 and basement membrane integrity: a unifying mechanism for progressive renal injury. FASEB J. 20, 1898–1900. 10.1096/fj.06-5898fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N. Y., Peng Y. M., Juang H. H., Chen T. C., Pan H. L., Chang G. W., et al. (2017). GPR56/ADGRG1 activation promotes melanoma cell migration via NTF dissociation and CTF-mediated galpha12/13/Rhoa signaling. J. Invest. Dermatol. 137, 727–736. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini F. (2010). GDNF/Ret signaling and renal branching morphogenesis: from mesenchymal signals to epithelial cell behaviors. Organogenesis 6, 252–262. 10.4161/org.6.4.12680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen M., Elzarrad M. K., Seaman S., Zudaire E., Stevens J., Yang M. Y., et al. (2011). GPR124, an orphan G protein-coupled receptor, is required for CNS-specific vascularization and establishment of the blood-brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5759–5764. 10.1073/pnas.1017192108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. A. (1999). The kidney development database. Dev. Genet. 24, 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declèves A. E., Sharma K. (2015). Obesity and kidney disease: differential effects of obesity on adipose tissue and kidney inflammation and fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 24, 28–36. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Lastra J. M., Shahein Y. E., Garrido J. J., Llanes D. (2003). Molecular cloning and structural analysis of the porcine homologue to CD97 antigen. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 93, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vivar Chevez R., Finke J., Bukowski R. (2014). The role of inflammation in kidney cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 816, 197–234. 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux G., Banfi S., Sultan M., Geffers L., Anand S., Rozado D., et al. (2011). A high-resolution anatomical atlas of the transcriptome in the mouse embryo. PLoS Biol. 9:e1000582. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S. E., Scholz M. J., Greer K. A., Hubbard A. D., Darnell D. K., Antin P. B., et al. (2006). Latrophilin-2 is a novel component of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition within the atrioventricular canal of the embryonic chicken heart. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3213–3221. 10.1002/dvdy.20973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler G. R. (2008). Epigenetics, development, and the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 2060–2067. 10.1681/ASN.2008010119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunér P., Al-Amily I. M., Soni A., Asplund O., Safi F., Storm P., et al. (2016). Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor G1 (ADGRG1/GPR56) and pancreatic beta-cell function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 4637–4645. 10.1210/jc.2016-1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt K. U., Coresh J., Devuyst O., Johnson R. J., Köttgen A., Levey A. S., et al. (2013). Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 382, 158–169. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faa G., Gerosa C., Fanni D., Monga G., Zaffanello M., Van Eyken P., et al. (2012). Morphogenesis and molecular mechanisms involved in human kidney development. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 1257–1268. 10.1002/jcp.22985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faizan M., Anwar S., Iqbal S., Mehmood Q., Zaman S., Abbas N., et al. (2014). Primary renal Ewing's sarcoma: a rare entity. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 24(Suppl. 1), S66–S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira F. M., Watanabe E. H., Onuchic L. F. (2015). Polycystins and molecular basis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, in Polycystic Kidney Disease, ed Li X. (Brisbane, QLD: Codon Publications; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibbe W. E., Rabelink T. J. (2017). Lupus nephritis: mesenchymal stromal cells in lupus nephritis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 452–453. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]