Abstract

Statin coverage has been examined among HIV-infected patients using Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines, although not with newer National Lipid Association (NLA) guidelines. We investigated statin eligibility, prescribing practices, and therapeutic responses using these three guidelines. Sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected between 2011 and 2016 for HIV-infected outpatients enrolled in the DC Cohort, a multi-center, prospective, observational study in Washington, DC. This analysis included patients aged ≥21 years receiving primary care at their HIV clinic site with ≥1 cholesterol result available. Of 3312 patients (median age 52; 79% black), 52% were eligible for statins based on ≥1 guideline, including 45% (NLA), 40% (ACC/AHA), and 30% (ATP III). Using each guideline, 49% (NLA), 56% (ACC/AHA), and 73% (ATP III) of eligible patients were prescribed statins. Predictors of new prescriptions included older age (aHR = 1.16 [1.08–1.26]/5 years), body mass index ≥30 (aHR = 1.50 [1.07–2.11]), and diabetes (aHR = 1.35 [1.03–1.79]). Hepatitis C coinfection was inversely associated with statin prescriptions (aHR = 0.67 [0.45–1.00]). Among 216 patients with available cholesterol results pre-/post-prescription, 53% achieved their NLA cholesterol goal after 6 months. Hepatitis C coinfection was positively associated (aHR = 1.87 [1.06–3.32]), and depression (aHR = 0.56 [0.35–0.92]) and protease inhibitor use (aHR = 0.61 [0.40–0.93]) were inversely associated, with NLA goal achievement. Half of patients were eligible for statins based on current US guidelines, with the highest proportion eligible based on NLA guidelines, yet, fewer received prescriptions and achieved treatment goals. Greater compliance with recommended statin prescribing practices may reduce cardiovascular disease risk among HIV-infected individuals.

Keywords: : HIV, statins, dyslipidemia, cholesterol, guidelines

Introduction

HIV-infected persons have a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared with the general population, attributed to the confluence of several factors, including a higher prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors among HIV-infected populations, chronic inflammation, and immune activation, related to HIV infection, and metabolic perturbations induced by antiretroviral (ARV) drugs.1 Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor for CVD that is common among HIV-infected persons and is often caused, in part, by HIV infection and/or the use of ARV drugs.2 The prevalence of dyslipidemia in large HIV cohort studies has ranged from 31% to 81% based on various definitions used for dyslipidemia.3–8

As dyslipidemia is a modifiable CVD risk factor that can be targeted therapeutically with lipid-lowering agents, namely statins, cholesterol treatment guidelines designed for the general population provide important guidance for determining whether to recommend statin therapy to HIV-infected persons. Building on the Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults [Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guidelines] that was last revised in 2004,9,10 two contemporary United States (US) national evidence-based guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia and prevention of CVD were issued by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and the National Lipid Association (NLA).11–13

The 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults identified four groups of individuals expected to benefit from statin therapy, including those with CVD, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥190 mg/dL, diabetes, or an estimated 10-year CVD risk ≥7.5% based on new Pooled Cohort Equations.11

Alternatively, the 2014 National Lipid Association Recommendations for Patient-Centered Management of Dyslipidemia specified the concentrations of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C)—the stated primary target for modification with statin therapy, calculated as total cholesterol minus HDL-C—for each of four CVD risk stratification categories, above which individuals should be considered for statin therapy.12 Unlike the ACC/AHA guidelines, the NLA guidelines also specified that HIV infection may be considered as an additional major CVD risk factor influencing a healthcare provider's decision to recommend statin therapy.

Numerous studies have used the 2004 ATP III and/or 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines to assess statin eligibility, coverage, and treatment outcomes among HIV-infected patient populations.8,14–23 Studies have consistently found that compliance with the statin prescribing recommendations described in the ACC/AHA guidelines would result in greater proportions of patients being prescribed statin therapy than based on the ATP III guidelines.17–19,21,23

However, in a nationally representative sample of adult patients at physician offices and hospital outpatient clinics between 2006 and 2013, only 24% of visits for HIV-infected patients with an indication for statin therapy, based on ATP III or ACC/AHA guidelines, resulted in statin prescriptions, compared with 36% of visits for HIV-uninfected patients; a similar gap in prescriptions between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients was found for aspirin/antiplatelet agents.24 Physicians in the US generally underused guideline-recommended prescribing practices for CVD prevention medications, especially with HIV-infected patients.

Further, emerging evidence suggests that even high compliance with the ACC/AHA guidelines may result in statin undertreatment for HIV-infected persons. In two studies that applied the ACC/AHA guidelines to HIV-infected patients, one-third of those who had a CVD event would not have been recommended statin therapy before the event and nearly three-quarters of those with high-risk coronary plaque features by cardiac computed tomography would not have been recommended statin therapy.17,21

To date, however, no studies have used the 2014 NLA guidelines, which takes a more comprehensive patient-centered approach to CVD risk management than the ACC/AHA guidelines,25 to investigate statin coverage or dyslipidemia treatment outcomes among HIV-infected persons. Thus, the concordance of statin recommendations using NLA versus other guidelines and the impact of the use of the NLA guidelines on conclusions regarding statin coverage in this population are unknown. Given that a rising proportionate CVD mortality among HIV-infected persons has been observed in recent years,26 evaluation of the clinical management of dyslipidemia in HIV care settings may point to important statin treatment opportunities and inform key CVD prevention service needs for HIV-infected patients.

In this analysis, we compared proportions of HIV-infected patients who were eligible for statin therapy based on three US national cholesterol guidelines, examined actual statin prescribing practices, and evaluated patients' clinical responses to newly prescribed statin therapy. We also assessed predictors of being newly prescribed a statin and of achieving cholesterol goals.

Methods

Study population

We analyzed data from the DC Cohort study, an ongoing, prospective, multi-center observational cohort study of HIV-infected outpatients at 13 major community, academic, and government clinical sites in Washington, DC; the methods of this study have been described previously.27 In brief, HIV-infected patients were enrolled on an ongoing basis beginning in January 2011 and prospectively followed from the visit at which informed consent was provided. Sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data documented in outpatient electronic medical record (EMR) systems were routinely monitored and abstracted into the DC Cohort database. The protocol was approved by multiple Institutional Review Boards including the George Washington University.

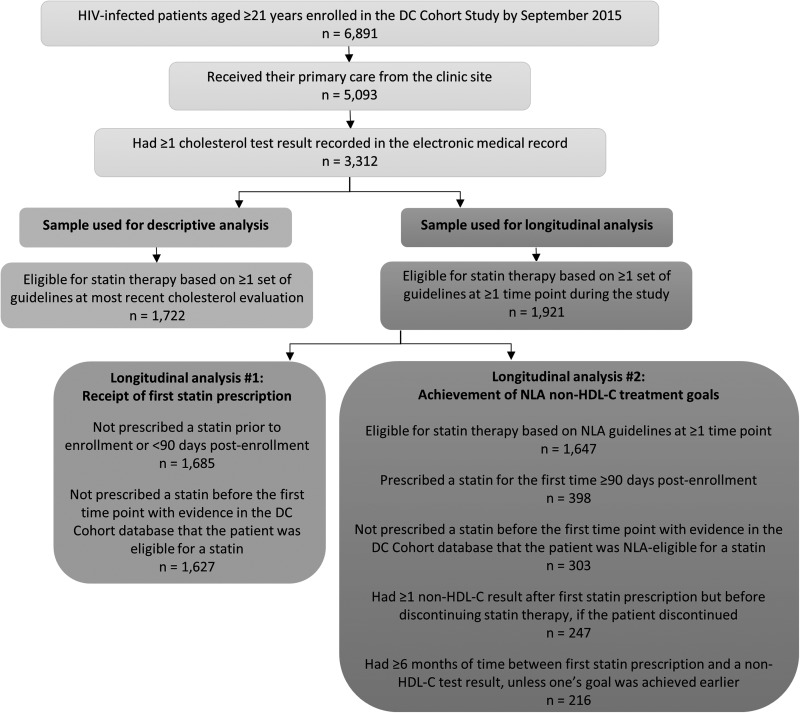

For this analysis, DC Cohort study participants were included if they were enrolled by September 2015, were ≥21 years of age (i.e., the age group to which all three sets of cholesterol guidelines apply), and received their primary care at the clinic site, so that patients whose CVD risk factors would have been managed as part of the care received at their site were included, and that clinical information relevant to this analysis (e.g., statin prescriptions) was accessible. Another inclusion criterion was having ≥1 cholesterol result available during the study period, which was used to determine whether patients met eligibility criteria for statin treatment (Fig. 1). Data collected between January 2011 and January 2016 contributed to this analysis.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of selection of DC Cohort study participants for descriptive and longitudinal analyses.

Measures

ATP III, ACC/AHA, and NLA dyslipidemia treatment guidelines were applied to available DC Cohort data to determine whether patients had an indication for statin therapy (detailed criteria provided in Supplementary Data 1 at www.liebertpub.com/apc).9,11,12 Whether patients were prescribed statin therapy, based on documented prescriptions for atorvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, or pitavastatin, was used as a measure for statin treatment because prescription pickup data and medication adherence data were not available in the DC Cohort database. Similarly, data on doses prescribed were largely unavailable so we were unable to examine statin potency in this analysis.

Achievement of 2014 NLA statin treatment goals was defined by whether one's non-HDL-C concentration decreased below the desired threshold after 6 months of a new statin prescription unless one's goal was achieved earlier (but before statin discontinuation if a patient discontinued): <130 mg/dL if at low, moderate, or high CVD risk, and <100 mg/dL if at very high risk.12

While both non-HDL-C and LDL-C are considered primary targets for modification, the NLA Expert Panel emphasizes the importance of non-HDL-C as a target because it is a stronger predictor of CVD morbidity and mortality than LDL-C and it constitutes the cholesterol carried by all potentially atherogenic particles, including LDL, intermediate-density lipoproteins, very low-density lipoproteins, chylomicron remnants, and lipoprotein(a).12 Non-HDL-C is also more accurately measured in the nonfasting state compared with LDL-C.12 Although the NLA guidelines were not released until 2014, these treatment goals were used to determine whether non-HDL-C levels decreased to the extent desired—regardless of date of first statin prescription—based on the current state of evidence, and also because treatment goals were not provided in the ACC/AHA guidelines.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex at birth, race/ethnicity, and type of health insurance. Behavioral covariates included histories of smoking and recreational drug use at enrollment (current, previous, or never).

Comorbidities of interest included depression diagnosis, anxiety/stress disorder diagnosis, hypertension (defined by a diagnosis, an antihypertensive medication prescription, or two most recent blood pressure results ≥140/90 mm Hg within the last year), diabetes (defined by a diagnosis, an antidiabetes medication prescription, or either two most recent serum glucose results ≥200 mg/dL or two most recent hemoglobin A1c results ≥6.5% within the last year), body mass index (BMI) category, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (defined by a diagnosis, reactive HCV antibody test result, positive qualitative RNA test result, or a detectable quantitative RNA viral load test result), chronic kidney disease diagnosis, and liver disease diagnosis or abnormal liver function test abnormality [most recent alanine transaminase (ALT) ≥55/40 U/L (males/females) or aspartate transaminase (AST) ≥50 U/L within the last year].

HIV-specific factors included HIV transmission category, length of time since HIV diagnosis, history of AIDS diagnosis, most recent CD4 cell count, nadir CD4 cell count, most recent HIV RNA viral load, and current ARV regimen, classified as protease inhibitor-based (PI-based), non-PI-based, or none, as PI-based regimens have been specifically implicated in increasing serum concentrations of atherogenic cholesterol.28

Statistical analysis

We used data available through each patient's most recent cholesterol evaluation to calculate proportions of patients with a statin indication at that specific time point based on each of the three guidelines and based on ≥1 of these guidelines to determine the overall proportion of patients who might benefit from statin therapy. To minimize misclassification, we defined patients who were prescribed statin therapy at any point during the study follow-up period as being eligible based on each of the three guidelines since available cholesterol results for those patients during their time enrolled in the DC Cohort study could have been influenced by prior statin use (they likely had a statin indication regardless of the data points available and we were generally unable to determine which guidelines would have recommended prescribing statin therapy to those patients before their first prescription).

For NLA guidelines, we calculated the proportion of patients with a statin indication based on the recommendations designed for the general population and also after counting HIV infection as one of the major CVD risk factors used to determine statin eligibility in the NLA risk stratification algorithm (in addition to older age, cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, and low HDL-C).

We also calculated the proportion of patients with a statin indication who received a statin prescription and, among those who received a new prescription (i.e., having one's first documented prescription ≥90 days post-enrollment), the proportion who achieved their cholesterol treatment goals (Fig. 1).

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression with time-updated covariates was used to identify predictors of receiving a new statin prescription and of achieving one's cholesterol treatment goal.

For modeling time to first statin prescription, patients with a statin indication based on ≥1 guideline contributed person-time from the first date ≥90 days post-enrollment when there was evidence in the EMR of a statin indication until the first prescription date, the last consecutive date when there was evidence of an indication, or the end of follow-up, whichever was earliest. For that analysis, we longitudinally reassessed whether patients were eligible for statin therapy at each time point when new data were available (e.g., new clinic visits during which relevant data were collected). Although the ACC/AHA and NLA guidelines were published in the middle of the study period, we opted to use those guidelines for this longitudinal analysis so that an analytic subsample reasonably expected to benefit from statin therapy was most accurately defined.

For modeling time to goal achievement, patients with available non-HDL-C results both before and after first statin prescription contributed person-time from the date of first prescription until the first date of a non-HDL-C result below one's goal threshold or the last date ≥6 months after first prescription (but before statin discontinuation, if a patient discontinued) with a new non-HDL-C result, whichever was earlier. The proportional hazards assumption was verified for covariates by inspecting Kaplan–Meier survival plots and Schoenfeld residual plots.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, and covariates with p < 0.20 in univariable analyses were included in multivariable models. The multivariable model for first statin prescription also included study site and lipid test results. Two multivariable models for non-HDL-C goal achievement were created, one with and one without inclusion of the reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's individual treatment goal, to explore the effect of its adjustment on results.

Missing data, which generally resulted from specific fields not having been discretely captured in the EMR, were multiply imputed for HIV transmission category (2% missing), smoking (18% missing), and recreational drug use (36% missing). Using the PROC MI procedure in SAS, we implemented the fully conditional specification method of multiple imputations, which included the use of the discriminant function method for imputing categorical variables.29 This procedure assumes that missing data are missing at random, that is, that the probability that a value is missing depends only on measured data. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS, Version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Of 6891 HIV-infected patients aged ≥21 years in the DC Cohort study, 5093 received primary care from their HIV care site, of whom 3312 also had ≥1 cholesterol result available for this analysis. Differences between patients included in this analysis and patients excluded from this analysis are described in Supplementary Data 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, as of the date of patients' most recent cholesterol test, are presented in Table 1 for all patients included in this analysis, for those with a statin indication, and for those with a statin prescription. Overall, the median age was 52 years (IQR: 44–58), 2581 (78%) were male, and 2602 (79%) were non-Hispanic black. In terms of CVD risk factors, 1650 (50%) had hypertension, 616 (19%) had diabetes, 1003 (30%) had a BMI ≥30, 554 (17%) had non-HDL-C ≥160 mg/dL, 515 (16%) had LDL-C ≥130 mg/dL, 860 (26%) had HDL-C <40 mg/dL, 236 (7%) had total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, and 581 (18%) had triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of HIV-Infected Primary Care Patients in the DC Cohort Study (n = 3312)

| All patients (n = 3312)a n (%) | Patients with an indication for statin therapy (n = 1722)b n (%) | Patients prescribed statin therapy (n = 731)c n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 52 (44–58) | 56 (50–61) | 57 (51–63) |

| ≥60 | 682 (20.6) | 519 (30.1) | 283 (38.7) |

| Male sex at birth | 2581 (77.9) | 1371 (79.6) | 609 (83.3) |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 2602 (78.7) | 1375 (79.9) | 557 (76.2) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 469 (14.2) | 246 (14.3) | 124 (17.0) |

| Hispanic | 184 (5.6) | 72 (4.2) | 35 (4.8) |

| Other | 51 (1.5) | 27 (1.6) | 14 (1.9) |

| Publically insurede | 2515 (75.9) | 1383 (80.3) | 568 (77.7) |

| Any history of smoking (current or previous)d | 1851 (67.7) | 1076 (72.1) | 436 (60.1) |

| Current smoker | 1275 (46.7) | 718 (48.1) | 250 (38.5) |

| Any history of recreational drug use (current or previous)d | 1224 (57.9) | 669 (58.0) | 255 (47.3) |

| Current recreational drug use | 400 (18.9) | 169 (14.7) | 52 (9.7) |

| Depression diagnosis | 746 (22.5) | 416 (24.2) | 191 (26.1) |

| Anxiety/stress disorder diagnosis | 369 (11.1) | 204 (11.9) | 78 (10.7) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.1 (23.6–31.0) | 27.9 (24.4–31.9) | 28.0 (24.8–32.0) |

| 25-<30 (overweight) | 1142 (34.6) | 607 (35.3) | 262 (35.9) |

| ≥30 (obese) | 1003 (30.4) | 613 (35.7) | 273 (37.4) |

| Hypertension | 1650 (49.8) | 1225 (71.1) | 546 (74.7) |

| Uncontrolled hypertensionf | 343 (10.4) | 259 (15.0) | 98 (13.4) |

| Diabetes | 616 (18.6) | 578 (33.6) | 256 (35.0) |

| Hepatitis C infectiong | 636 (19.2) | 402 (23.3) | 110 (15.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease diagnosis | 214 (6.5) | 175 (10.2) | 82 (11.2) |

| Liver disease or abnormality | 231 (7.0) | 135 (7.8) | 39 (5.3) |

| Length of time since HIV diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 14 (9–21) | 17 (11–23) | 17 (11–23) |

| History of AIDS diagnosis | 2104 (63.5) | 1165 (67.7) | 496 (67.9) |

| Nadir CD4 cell count (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 252 (108–400) | 242 (101–397) | 239 (100–380) |

| <200 | 1354 (40.9) | 746 (43.3) | 316 (43.2) |

| 200–500 | 1482 (44.8) | 730 (42.4) | 314 (43.0) |

| Most recent CD4 cell count (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 578 (391–788) | 594 (412–812) | 617 (443–848) |

| <200 | 231 (7.0) | 105 (6.1) | 31 (4.2) |

| 200–500 | 1042 (31.5) | 503 (29.2) | 204 (27.9) |

| Most recent viral load ≥200 copies/mL | 499 (15.4) | 188 (11.1) | 56 (7.9) |

| Current use of ARV therapyh | 3129 (94.5) | 1631 (94.7) | 699 (95.6) |

| NNRTI based | 1263 (38.1) | 675 (39.2) | 336 (46.0) |

| PI based | 1492 (45.1) | 794 (46.1) | 317 (43.4) |

| INSTI based | 1092 (33.0) | 661 (38.4) | 290 (39.7) |

| CCR5 inhibitor based | 36 (1.1) | 27 (1.6) | 10 (1.4) |

All patients who received primary care at their clinic site and had ≥1 cholesterol result recorded in their electronic medical record.

Patients who had an indication for statin therapy, as of the date of their most recent cholesterol measurement, based on at least one of three guidelines—2004 Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III guidelines, 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, and 2014 National Lipid Association (NLA) guidelines—or who received a statin at any point during the follow-up period.

Patients who were prescribed a statin at any point during the follow-up period. Of the 731 patients prescribed a statin at least once, 568 had a current active statin prescription at the time of their most recent cholesterol evaluation.

Based on the data available in the 3312 patients' electronic medical records, 6 patients (0.2%) were missing a value for race/ethnicity, 579 (17.5%) for smoking history, and 1198 (36.2%) for recreational drug use history.

Public insurance was defined as Medicare, Medicaid, Ryan White or AIDS Drug Assistance Program, DC Alliance, or other public health insurance.

Among patients with hypertension, uncontrolled hypertension was defined as having their two most recent blood pressure test results ≥140/90 mm Hg (within the last year).

Hepatitis C infection includes chronic, acute, and resolved infections. Of the 636 patients with hepatitis C infection, 601 (94.5%) were diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C.

ARV regimen categories are not mutually exclusive.

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; ARV, antiretroviral; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; INSTI, integrase inhibitor.

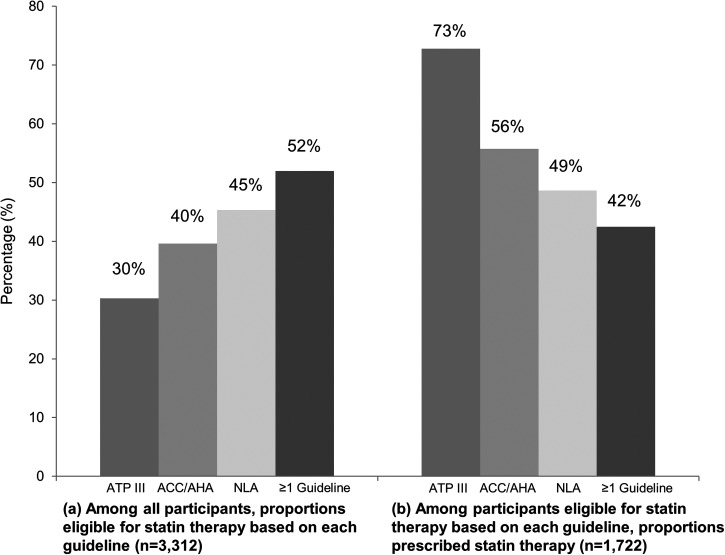

Of the 3312 patients with at least one cholesterol result available for this analysis, 1004 (30%), 1312 (40%), 1502 (45%), and 1722 (52%) had a statin indication, as of the date of their most recent cholesterol evaluation, based on ATP III guidelines, ACC/AHA guidelines, NLA guidelines, and ≥1 set of guidelines, respectively (Fig. 2). Of the 1722 patients with an indication based on ≥1 set of guidelines, 918 (53%) had an indication based on all three guidelines, while 331 (19%) had an indication based on NLA guidelines only, 212 (12%) based on ACC/AHA guidelines only, and 176 (10%) based on NLA and ACC/AHA, but not ATP III, guidelines (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Proportions of HIV-infected outpatients who were eligible for statin therapy and who were prescribed statin therapy (n = 3312). Data available as of the date of each patient's most recent cholesterol measurement were used to define whether a statin was indicated based on the 2004 Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III guidelines, 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines, and 2014 National Lipid Association (NLA) guidelines.

FIG. 3.

Concordance of recommendations for statin therapy based on three cholesterol treatment guidelines among 1722 HIV-infected outpatients eligible for statin therapy.

After HIV infection was counted as one of the major CVD risk factors used to determine statin eligibility in the NLA risk stratification algorithm, 1679 patients (51%) had an indication based on NLA guidelines, resulting in 1884 patients (57%) having had an indication based on ≥1 set of guidelines after that modification.

Among all 3312 patients, 731 (22%) received a statin prescription at some point during the study follow-up period from 2011 to 2016. Of those patients, 396 (54%) had at least one prescription for atorvastatin, 284 (39%) for pravastatin, 132 (18%) for rosuvastatin, 71 (10%) for simvastatin, 5 (0.7%) for fluvastatin, 3 (0.4%) for lovastatin, and 3 (0.4%) for pitavastatin. The 731 patients with a statin prescription represent 73%, 56%, 49%, and 42% of patients with a statin indication based on ATP III guidelines, ACC/AHA guidelines, NLA guidelines, and ≥1 set of guidelines, respectively (Fig. 2).

Excluding patients who had previously been prescribed statin therapy before their enrollment in the study, 374 (23%) of 1627 patients eligible for statin therapy based on ≥1 guideline during the follow-up period received a new statin prescription. Older age [adjusted HR (aHR) = 1.16 [95% CI: 1.08–1.26] per 5-year increase], BMI ≥30 (aHR = 1.50 [95% CI: 1.07–2.11]), and diabetes (aHR = 1.35 [95% CI: 1.03–1.79]) were predictors of receiving a new statin prescription (Table 2). HCV-coinfected patients were less likely to receive a statin prescription (aHR = 0.67 [95% CI: 0.45–1.00]).

Table 2.

Predictors of Being Newly Prescribed Statin Therapy Among 1627 HIV-Infected Outpatients with a Statin Indication (1886 Person-Years)

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Category | HR | 95% CI | p | aHR | 95% CI | p |

| Age (years)b | 1.11 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.003 | 1.16 | 1.08–1.26 | <0.001 | |

| Male sex at birth | 1.06 | 0.80–1.42 | 0.68 | 1.26 | 0.85–1.87 | 0.26 | |

| Race/ethnicity | NH white | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| NH black | 0.78 | 0.56–1.08 | 0.13 | 0.99 | 0.68–1.44 | 0.96 | |

| Hispanic | 1.23 | 0.69–2.22 | 0.48 | 1.89 | 0.99–3.59 | 0.053 | |

| HIV transmission category | MSM | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| Heterosexual | 1.20 | 0.92–1.56 | 0.18 | 1.25 | 0.89–1.76 | 0.20 | |

| IDU | 0.64 | 0.46–0.91 | 0.012 | 1.19 | 0.76–1.88 | 0.44 | |

| Public versus private insurance | 0.80 | 0.58–1.10 | 0.17 | 1.09 | 0.74–1.63 | 0.66 | |

| Smoking history | Never | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| Current | 0.73 | 0.53–0.99 | 0.046 | 1.09 | 0.75–1.58 | 0.67 | |

| Previous | 1.02 | 0.71–1.47 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 0.74–1.69 | 0.60 | |

| Recreational drug use | Never | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| Current | 0.53 | 0.35–0.81 | 0.004 | 0.70 | 0.42–1.16 | 0.17 | |

| Previous | 0.61 | 0.45–0.84 | 0.003 | 0.81 | 0.53–1.22 | 0.31 | |

| Depressionc | 1.27 | 0.96–1.67 | 0.090 | 1.24 | 0.93–1.65 | 0.15 | |

| Anxiety/stress disorderc | 1.04 | 0.71–1.53 | 0.85 | — | — | — | |

| BMI categoryc | <25 | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| 25-<30 | 1.26 | 0.92–1.71 | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.84–1.60 | 0.36 | |

| ≥30 | 1.32 | 0.97–1.79 | 0.080 | 1.50 | 1.07–2.11 | 0.019 | |

| Hypertensionc | None | ref | — | — | — | — | — |

| Controlled | 1.04 | 0.80–1.36 | 0.76 | — | — | — | |

| Uncontrolled | 0.96 | 0.65–1.41 | 0.83 | — | — | — | |

| Diabetesc | 1.19 | 0.93–1.53 | 0.17 | 1.35 | 1.03–1.79 | 0.033 | |

| Hepatitis C infectionc | 0.56 | 0.40–0.76 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.45–1.00 | 0.049 | |

| Chronic kidney diseasec | 1.02 | 0.66–1.58 | 0.92 | — | — | — | |

| Liver disease or abnormalityc | 1.04 | 0.69–1.56 | 0.87 | — | — | — | |

| Length of time since HIV diagnosis (years)b | 1.00 | 0.92–1.08 | 0.91 | — | — | — | |

| AIDS diagnosisc | 1.17 | 0.90–1.52 | 0.25 | — | — | — | |

| Nadir CD4 cell count (cells/μL)c | >500 | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| 200–500 | 1.19 | 0.80–1.77 | 0.40 | 1.07 | 0.71–1.60 | 0.75 | |

| <200 | 1.41 | 0.95–2.08 | 0.086 | 0.98 | 0.65–1.47 | 0.93 | |

| Recent CD4 cell count (cells/μL)c | >500 | ref | — | — | — | — | — |

| 200–500 | 1.05 | 0.81–1.36 | 0.70 | — | — | — | |

| <200 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.78 | 0.60 | — | — | — | |

| Recent viral load ≥200 copies/mLc | 0.75 | 0.51–1.11 | 0.15 | 1.06 | 0.71–1.59 | 0.77 | |

| ARV regimenc | Non-PI based | ref | — | — | — | — | — |

| PI based | 0.95 | 0.74–1.21 | 0.67 | — | — | — | |

| None | 0.72 | 0.39–1.34 | 0.31 | — | — | — | |

Hazard ratios were adjusted for site, age, sex, race/ethnicity, time-updated lipid results (total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides), and all covariates listed with p < 0.20 in unadjusted models.

Per 5-year increase.

Time-updated covariate.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; NH, non-Hispanic; MSM, men who have sex with men; IDU; injection drug use.

Bold text indicates p < 0.05.

Among the patients who were newly prescribed statin therapy, 216 had available data to determine whether their NLA non-HDL-C goal was achieved after 6 months. Among these patients, 114 (53%) successfully achieved their goal, including 80% of the 15 patients at low CVD risk, 56% of the 18 patients at moderate CVD risk, 57% of the 91 patients at high CVD risk, and 44% of the 92 patients at very high CVD risk. The median decrease in non-HDL-C was 43 mg/dL (IQR: 17–73), but was 61.5 mg/dL (IQR: 43–84) among patients who achieved their goal and only 20.5 mg/dL (IQR: 0–44) among patients who did not achieve their goal.

As a sensitivity analysis, we also assessed most recent non-HDL-C concentration among all patients with a statin prescription, regardless of whether there were cholesterol results available before the first prescription: among all 731 patients who received a statin prescription during the study period, 567 had a current prescription on the date of their most recent cholesterol evaluation; of these 567 patients, 264 (46%) had non-HDL-C <130 mg/dL at their most recent evaluation, which occurred a median of 26 months (IQR: 11–41) after one's first statin prescription.

HCV-coinfection (aHR = 1.87 [95% CI: 1.06–3.32]) was a predictor of achieving one's non-HDL-C treatment goal after 6 months (Table 3). Without adjustment for the reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's goal, depression (aHR = 0.56 [95% CI: 0.35–0.92]) and the current use of a PI-based ARV regimen (aHR = 0.61 [95% CI: 0.40–0.93]) were predictive of a lower likelihood of achieving one's goal.

Table 3.

Predictors of Achieving Non-HDL-C Goals Among 216 HIV-Infected Outpatients Newly Prescribed Statin Therapy (308 Person-Years)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted model 1a | Adjusted model 2b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Category | HR | 95% CI | p | aHR | 95% CI | p | aHR | 95% CI | p |

| Age (years) c | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.84–1.09 | 0.47 | 0.94 | 0.83–1.07 | 0.36 | |

| Male sex at birth | 1.60 | 0.93–2.75 | 0.092 | 1.55 | 0.85–2.80 | 0.15 | 1.22 | 0.66–2.25 | 0.52 | |

| Race/ethnicity | NH white | ref | — | — | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| NH black | 0.80 | 0.48–1.31 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 0.47–1.53 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.47–1.53 | 0.57 | |

| Hispanic | 2.18 | 1.01–4.70 | 0.047 | 1.86 | 0.75–4.63 | 0.18 | 2.47 | 0.98–6.23 | 0.055 | |

| Transmission category | MSM | ref | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Heterosexual | 0.82 | 0.54–1.25 | 0.35 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| IDU | 1.13 | 0.68–1.88 | 0.64 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Public versus private insurance | 0.64 | 0.40–1.01 | 0.057 | 0.79 | 0.45–1.38 | 0.40 | 0.76 | 0.43–1.33 | 0.33 | |

| Smoking history | Never | ref | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Current | 1.21 | 0.76–1.93 | 0.42 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Previous | 1.05 | 0.62–1.76 | 0.87 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Recreational drug use | Never | ref | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Current | 0.95 | 0.50–1.81 | 0.88 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Previous | 1.00 | 0.66–1.52 | 0.99 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Depressiond | 0.69 | 0.44–1.07 | 0.095 | 0.56 | 0.35–0.92 | 0.022 | 0.63 | 0.39–1.03 | 0.066 | |

| Anxiety/stress disorderd | 0.83 | 0.43–1.59 | 0.57 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| BMI categoryd | <25 | ref | — | — | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| 25-<30 | 0.81 | 0.51–1.29 | 0.38 | 0.86 | 0.53–1.39 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.56–1.47 | 0.68 | |

| ≥30 | 0.70 | 0.43–1.12 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0.51–1.51 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.51–1.49 | 0.60 | |

| Hypertensiond | None | ref | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Controlled | 0.99 | 0.65–1.50 | 0.95 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Uncontrolled | 0.91 | 0.51–1.63 | 0.75 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Diabetesd | 0.81 | 0.54–1.21 | 0.30 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Hepatitis C infectiond | 1.49 | 0.90–2.48 | 0.12 | 2.08 | 1.17–3.69 | 0.012 | 1.87 | 1.06–3.32 | 0.032 | |

| Chronic kidney diseased | 0.64 | 0.23–1.73 | 0.37 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Liver disease or abnormalityd | 0.99 | 0.48–2.04 | 0.99 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Length of time since HIV diagnosis (years)c | 1.07 | 0.94–1.20 | 0.32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| AIDS diagnosisd | 0.75 | 0.51–1.10 | 0.14 | 1.20 | 0.68–2.10 | 0.53 | 1.19 | 0.67–2.11 | 0.95 | |

| Nadir CD4 cell count (cells/μL)d | >500 | ref | — | — | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| 200–500 | 0.55 | 0.31–0.97 | 0.040 | 0.54 | 0.28–1.03 | 0.060 | 0.65 | 0.34–1.26 | 0.14 | |

| <200 | 0.46 | 0.26–0.80 | 0.006 | 0.54 | 0.25–1.15 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.27–1.26 | 0.17 | |

| Recent CD4 cell count (cells/μL)d | >500 | ref | — | — | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| 200–500 | 0.73 | 0.49–1.10 | 0.13 | 0.82 | 0.51–1.33 | 0.42 | 0.92 | 0.57–1.48 | 0.72 | |

| <200 | 0.83 | 0.34–2.07 | 0.70 | 1.20 | 0.44–3.25 | 0.72 | 1.57 | 0.58–4.29 | 0.38 | |

| Recent viral load ≥200 copies/mLd | 0.81 | 0.39–1.66 | 0.56 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| ARV regimend | Non-PI based | ref | — | — | ref | — | — | ref | — | — |

| PI based | 0.61 | 0.42–0.89 | 0.011 | 0.61 | 0.40–0.93 | 0.023 | 0.72 | 0.47–1.11 | 0.13 | |

| None | 0.65 | 0.24–1.78 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.19–1.68 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.17–1.62 | 0.27 | |

| Reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's goal (mg/dL)e | 0.86 | 0.81–0.92 | <0.001 | — | — | — | 0.87 | 0.81–0.92 | <0.001 | |

In model 1, hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and all covariates listed with p < 0.20 in unadjusted models.

In model 2, hazard ratios were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, all covariates listed with p < 0.20 in unadjusted models, and reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's treatment goal.

Per 5-year increase.

Time-updated covariate.

Per 10-mg/dL greater reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's goal.

Non-HDL-C, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Bold text indicates p < 0.05.

Discussion

We compared statin recommendations for HIV-infected primary care patients in a large and diverse cohort using the historically well-utilized ATP III guidelines and the newer ACC/AHA and NLA guidelines. Notably, this study is the first to our knowledge to use the NLA guidelines to assess statin coverage and dyslipidemia treatment outcomes among HIV-infected persons.

Our findings demonstrate that a large proportion of HIV-infected patients had documented evidence in the DC Cohort database of having an indication for statin therapy based on published guidelines and that opportunities remain for the expansion of the use of statin therapy to treat dyslipidemia and prevent CVD among HIV-infected patients. Moreover, many patients who were newly prescribed statin therapy did not successfully achieve their NLA treatment goals, suggesting that statin adherence support and/or the additional promotion of lifestyle modification interventions to reduce CVD risk might benefit HIV-infected patients taking statins.

More than half of patients had a statin indication based on at least one of the three guidelines, with the largest number having had an indication based on the NLA guidelines, followed by the ACC/AHA guidelines. The proportion of patients with a statin indication who received a prescription was the lowest—less than half—among those with an indication based on NLA guidelines.

Proportions of DC Cohort patients eligible for statin therapy based on ATP III and ACC/AHA guidelines were largely consistent with those found in other studies of HIV-infected patients. Compared with the 30% of DC Cohort patients who were eligible for statin therapy based on ATP III guidelines, 26% of HIV-infected patients at two Boston hospitals,21 28% at five US Veterans Affairs medical centers,14 35% at a New York City clinic,8 and 45% of a national sample of veterans were previously determined to be eligible based on ATP III guidelines.19 Similar to the 40% of DC Cohort patients who were eligible based on the ACC/AHA guidelines, 42% of HIV-infected patients at two Boston hospitals21 and 42% at a Chicago clinic were determined to be eligible,22 although 64% of US veterans were also determined to be eligible based on ACC/AHA guidelines.19

While virtually all patients eligible for statin therapy based on the ATP III guidelines were also eligible based on the ACC/AHA and/or NLA guidelines, nearly one-third of those eligible based on at least one set of guidelines were eligible based on only ACC/AHA or only NLA guidelines. This finding can be explained by the guidelines' somewhat different approaches.25 The ACC/AHA defined major “statin benefit groups”—individuals with CVD, LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, diabetes (if 40–75 years of age), or estimated 10-year CVD risk ≥7.5%, quantified using new sex- and race-specific risk equations developed using data pooled from various cohort studies.11

The NLA alternatively focused on identifying patients with “very high-risk” or “high-risk” conditions and counting the number of CVD risk factors present (e.g., high blood pressure, cigarette smoking, low HDL-C) to classify individuals into one of four CVD risk categories. One's assigned risk category would then determine the non-HDL-C or LDL-C threshold at which one would be deemed eligible for statin therapy.12 In addition, the NLA guidelines provide specific considerations for groups at increased risk of CVD, including people with HIV, in that HIV infection may be considered an additional major CVD risk factor influencing a physician's decision to recommend statin therapy.13

After HIV infection was counted as an additional major CVD risk factor in the NLA risk stratification algorithm, more than half of patients in this study sample were eligible for statin therapy based on the NLA guidelines alone. Interestingly, the use of HIV infection as an additional major CVD risk factor only resulted in an additional 6% of patients being considered eligible for statin therapy based on the NLA guidelines, indicating that the large majority of patients who were determined to be eligible based on those guidelines would have been considered eligible regardless of whether HIV infection was counted as a major CVD risk factor.

As might be expected, patients with CVD risk factors, including older age, obesity, and diabetes, were more likely to receive a new statin prescription. Current smokers (before adjustment for other factors) and HCV-coinfected patients were less likely to receive a statin prescription, which has also been observed in other HIV cohorts.14,18,19 Current smokers should be targeted for statin therapy (in the presence of other risk factors and/or high cholesterol), particularly since smoking has been found to be associated with a greater risk of myocardial infarction in the HIV-infected population than in the general population.30

The gap in treatment among HCV-coinfected patients could be related to provider concern regarding potential hepatotoxicity.31,32 Data available to date, however, support the safety of statin use in the presence of liver disease or elevated liver enzymes, although statin use has not been evaluated in a controlled trial of HIV/HCV-coinfected persons.33–35 Two recent cohort studies of HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals demonstrated that statin use was associated with decreased liver disease progression.36,37

Among the subset of patients for whom we could assess goal achievement following a new statin prescription, only approximately half of patients achieved their NLA non-HDL-C goals. This is a smaller proportion than the 75% of HIV-infected patients at a New York City clinic and 87% of male patients in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort study who achieved their ATP III LDL-C goals.8,16

Additional research should explore whether nonadherence, insufficient dosage, and/or perhaps overly ambitious non-HDL-C treatment targets may play a role in the relatively low rate of treatment success. Other barriers to successfully controlling dyslipidemia could include perceived drug side effects, costs of statins, suboptimal physician provider/patient relationships, and overestimation of the effect of diet control.38 Regarding the effectiveness of statin therapy in HIV-infected populations, one prospective observational cohort study of HIV-infected patients found that statin use was associated with a significantly lower hazard of all-cause mortality;39 however, four other observational studies of HIV-infected patients did not find significant associations between statin use and various outcomes, including CVD events, non-AIDS events, and all-cause mortality.40–43

Interestingly, patients with newly prescribed statin therapy who were coinfected with HCV were more likely to achieve their non-HDL-C goals, even after adjusting for the reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's goal. This might be explained by the previously described “protective effect” of HCV coinfection against risk of dyslipidemia in HIV-infected persons, in that HIV/HCV-coinfected patients were found to have lower rates of dyslipidemia than HIV-monoinfected individuals in numerous studies.44–47 One hypothesized explanation for this lipid paradox is that heightened chronic inflammation in the setting of HIV/HCV-coinfection may affect the ability of the liver to synthesize lipoproteins.45 Despite lower cholesterol concentrations, evidence has suggested that HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals might confront a greater risk of CVD than HIV-monoinfected individuals, in part, due to higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.47

Depression and the current use of a PI-based ARV regimen were each associated with a lower likelihood of achieving one's non-HDL-C goal, although this association was not significant after adjusting for the reduction in non-HDL-C needed to meet one's goal. It is possible that patients with depression might have had lower statin adherence, as depression has been found to be associated with lower adherence to chronic disease medications, including ARV therapy.48 The association between PI-based regimens and adverse lipid profiles has been well described in the literature.28,49,50

This study has several limitations. First, data on statin adherence were not available and, thus, statin prescribing was used to calculate statin start and stop dates, which is comparable to an intent-to-treat approach. Nonadherence among patients who received a statin prescription would have resulted in misclassification of some statin nonusers as statin users and would have biased HRs for achieving cholesterol goals toward the null.

Second, we did not have information on patients' management of dyslipidemia using lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes, exercise, and smoking cessation; the use of such behavioral modifications might explain why some patients were not prescribed statin therapy. Third, data on family history of coronary heart disease were not available, so we were unable to consider that risk factor as part of applying ATP III and NLA guidelines to this cohort. Consequently, proportions of patients determined to be eligible for statin therapy based on those guidelines were likely underestimated.

Fourth, the analytical sample for regression modeling for achievement of cholesterol goals was limited to patients for whom we could calculate treatment goals based on available cholesterol results before and after one's first statin prescription, which limited statistical power. Fifth, there were missing data for behavioral variables, but values were multiply imputed for the purpose of regression modeling. This procedure requires the assumption that the data were missing at random, conditional on available data for measured covariates; if this assumption does not hold, the HR estimates obtained for variables with missing data may be biased.

Sixth, we used the non-HDL-C goals specified in the 2014 NLA guidelines to assess whether lipid targets were achieved, although these guidelines were released in the middle of the study period; thus, providers may not have specifically monitored cholesterol changes with NLA-recommended cholesterol reductions in mind. Seventh, we were unable to consider or adjust for statin potency when identifying predictors of achieving target cholesterol goals, as data on statin dose were not routinely available in the DC Cohort database.

Finally, opportunities for patients to be screened for dyslipidemia, initiate a statin regimen, and undergo regular cholesterol monitoring could have been affected by their own care-seeking behaviors. Although patients who did not receive primary care at their HIV clinic site and/or did not have documented cholesterol test results were excluded from this analysis, restricting the sample to HIV-infected patients engaged in primary care with evidence of cholesterol screening maximized the generalizability of findings to other similar populations.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that approximately half of HIV-infected primary care patients in a large urban cohort had an indication for statin therapy based on the newer US ACC/AHA and NLA dyslipidemia treatment guidelines. Given the increasing number of people aging with HIV, the expansion of the use of statin therapy to treat dyslipidemia represents one key approach for reducing CVD risk among HIV-infected patient populations experiencing elevated and growing rates of morbidity and mortality attributed to CVD.

The first large-scale trial to assess the efficacy of statin therapy specifically among HIV-infected persons, the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE), was launched in 2015 and will ultimately provide stronger scientific evidence on which physicians can base decisions regarding statin recommendations for HIV-infected patients.51 In the interim, it is recommended that HIV-infected patients on ARV drug regimens be treated with statins similarly to HIV-uninfected patients, as long as providers are mindful of drug/drug interactions between specific types of statins and ARV regimens.13,52,53 The ACC/AHA and NLA dyslipidemia treatment guidelines each provide important guidance that can inform physician recommendations regarding statin therapy for HIV-infected patients in the US.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the DC Cohort Executive Committee

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (Grant UM1AI069503). This publication was facilitated (in part) by the infrastructure and services provided by the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (P30AI117970), which is supported by the following NIH Cofunding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, NIGMS, NIDDK, and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

We thank the site principal investigators (PIs), research assistants (RAs), the community advisory board (CAB), the patients themselves, the DC Department of Health, and the National Institutes of Health for their contributions to the DC Cohort.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Martin-Iguacel R, Llibre JM, Friis-Moller N. Risk of cardiovascular disease in an aging HIV population: Where are we now? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee FJ, Carr A. Dyslipidemia in HIV-infected patients. In: Garg A, ed. Dyslipidemias: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Management. New York: Humana Press, 2015;155–176 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy ME, Greenberg AE, Hart R, et al. High burden of metabolic comorbidities in a citywide cohort of HIV outpatients: Evolving health care needs of people aging with HIV in Washington, DC. HIV Med 2017;18:724–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahmanesh M, Schultze A, Burns F, et al. The cardiovascular risk management for people living with HIV in Europe: How well are we doing? AIDS 2016;30:2505–2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friis-Moller N, Ryom L, Smith C, et al. An updated prediction model of the global risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-positive persons: The Data-collection on Adverse Effects of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:214–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sico JJ, Chang CC, So-Armah K, et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology 2015;84:1933–1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ Jr, et al. Disparities in prevalence of key chronic diseases by gender and race/ethnicity among antiretroviral-treated HIV-infected adults in the US. Antiviral Ther 2013;18:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myerson M, Poltavskiy E, Armstrong EJ, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia and hypertension in 4278 HIV outpatients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:370–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002;106:3143–3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CNB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:720–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:S1–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: Part 1—full report. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:129–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson TA, Maki KC, Orringer CE, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: Part 2. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:S1–S122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freiberg MS, Leaf DA, Goulet JL, et al. The association between the receipt of lipid lowering therapy and HIV status among veterans who met NCEP/ATP III criteria for the receipt of lipid lowering medication. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:334–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Buchacz K, et al. Provider compliance with guidelines for management of cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monroe AK, Fu W, Zikusoka MN, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and statin treatment by HIV status among Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study men. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015;31:593–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanni MV, Fitch KV, Feldpausch M, et al. 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2004 Adult Treatment Panel III cholesterol guidelines applied to HIV-infected patients with/without subclinical high-risk coronary plaque. AIDS 2014;28:2061–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagchi S, Patel P, Faramand R, et al. Underutilization of statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease among primarily African-American HIV-infected patients. J AIDS Clin Res 2015;6:499 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement ME, Park LP, Navar AM, et al. Statin utilization and recommendations among HIV- and HCV-infected veterans: A cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsamadisi P, Cha A, Kim E, Latif S. Statin use with the ATP III guidelines compared to the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines in HIV primary care patients. J Pharm Pract 2017;30:64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosepele M, Regan S, Meigs JB, et al. Application of new ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines to an HIV clinical care cohort. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015February23–26; Seattle, WA Abstract no. 734 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly SG, Krueger KM, Grant JL, et al. Statin prescribing practices in the comprehensive care for HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:e26–e29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todd JV, Cole SR, Wohl DA, et al. Underutilization of statins when indicated in HIV-seropositive and seronegative women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:447–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ladapo JA, Richards AK, DeWitt CM, et al. Disparities in the quality of cardiovascular care between HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected adults in the United States: A cross-sectional study. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:e007107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adhyaru BB, Jacobson TA. New cholesterol guidelines for the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: A comparison of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines with the 2014 National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. Cardiol Clin 2015;33:181–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feinstein MJ, Bahiru E, Achenbach C, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular mortality for HIV-infected adults in the United States: 1999 to 2013. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:214–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg AE, Hays H, Castel AD, et al. Development of a large urban longitudinal HIV clinical cohort using a web-based platform to merge electronically and manually abstracted data from disparate medical record systems: Technical challenges and innovative solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:635–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clotet B, Negredo E. HIV protease inhibitors and dyslipidemia. AIDS Rev 2002;5:19–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, De A. Multiple imputation by fully conditional specification for dealing with missing data in a large epidemiologic study. Int J Stat Med Res 2015;4:287–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen LD, Helleberg M, May MT, et al. Myocardial infarction among Danish HIV-infected individuals: Population-attributable fractions associated with smoking. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1415–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rzouq FS, Volk ML, Hatoum HH, et al. Hepatotoxicity fears contribute to underutilization of statin medications by primary care physicians. Am J Med Sci 2010;340:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bader T. Yes! Statins can be given to liver patients. J Hepatology 2012;56:305–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stroup JS, Harris B. Is statin therapy safe in patients with HIV/hepatitis C coinfection? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2010;23:111–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milazzo L, Menzaghi B, Corvasce S, et al. Safety of statin therapy in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:258–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrillo RP. Withholding statins in patients with underlying liver disease: Wise or unwise? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2010;23:113–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almaghlouth N, Sutcliffe C, Mehta S, et al. Statins are associated with decreased liver disease progression in HIV/HCV co-infected adults. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2:1268 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliver NT, Hartman CM, Kramer JR, Chiao EY. Statin drugs decrease progression to cirrhosis in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfected individuals. AIDS 2016;30:2469–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chee YJ, Chan HH, Tan NC. Understanding patients' perspective of statin therapy: Can we design a better approach to the management of dyslipidaemia? A literature review. Singapore Med J 2014;55:416–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore RD, Bartlett JG, Gallant JE. Association between use of HMG CoA reductase inhibitors and mortality in HIV-infected patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krsak M, Kent DM, Terrin N, et al. Myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality in cART-treated HIV patients on statins. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:307–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen LD, Kronborg G, Larsen CS, et al. Statin therapy and mortality in HIV-infected individuals; a Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e52828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overton ET, Kitch D, Benson CA, et al. Effect of statin therapy in reducing the risk of serious non-AIDS-defining events and nonaccidental death. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:1471–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lang S, Lacombe JM, Mary-Krause M, et al. Is impact of statin therapy on all-cause mortality different in HIV-infected individuals compared to general population? Results from the FHDH-ANRS CO4 cohort. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collazos J, Mayo J, Ibarra S, Cazallas J. Hyperlipidemia in HIV-infected patients: The protective effect of hepatitis C virus co-infection. AIDS 2003;17:927–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohli P, Ganz P, Ma Y, et al. HIV and hepatitis C–coinfected patients have lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol despite higher proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9): An apparent “PCSK9–lipid paradox.” J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diong C, Raboud J, Li M, Cooper C. HIV/hepatitis C virus and HIV/hepatitis B virus coinfections protect against antiretroviral-related hyperlipidaemia. HIV Med 2011;12:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedimo R, Ghurani R, Nsuami M, et al. Lipid abnormalities in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. HIV Med 2006;7:530–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1175–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Périard D, Telenti A, Sudre P, et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia in HIV-infected individuals treated with protease inhibitors. Circulation 1999;100:700–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stein JH. Dyslipidemia in the era of HIV protease inhibitors. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2003;45:293–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbert JM, Fitch KV, Grinspoon SK. HIV-related cardiovascular disease, statins, and the REPRIEVE trial. Top Antivir Med 2015;23:146–149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feinstein MJ, Achenbach CJ, Stone NJ, Lloyd-Jones DM. A systematic review of the usefulness of statin therapy in HIV-infected patients. Am J Cardiol 2015;115:1760–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chastain DB, Stover KR, Riche DM. Evidence-based review of statin use in patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 2017;8:6–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.