Abstract

In addition to the high prevalence of gender dysphoria among transgender youth, this population is at greater risk of suffering from additional mental health disorders, including social anxiety disorder, compared to their cisgender peers. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been established as an effective form of treatment for social anxiety disorder. It is recommended that therapists modify and adapt CBT when working with minority groups such as transgender youth to ensure that the treatment is efficacious and culturally sensitive. However, literature assessing the efficacy of CBT for transgender youth with mental health issues is scant. As a result, there is no empirical literature on effective treatment for transgender youth who meet criteria for social anxiety disorder alone or youth who meet criteria for social anxiety disorder and gender dysphoria. This literature review aims to identify current research related to prevalence of mental health disorders in transgender youth, the current literature on adaptations of cognitive behavioral techniques, and the need for treatment research on adaptation of CBT for transgender individuals, specifically those with social anxiety disorder and gender dysphoria.

Keywords: : adaptations of cognitive behavioral therapy, gender dysphoria, social anxiety disorder, transgender youth

Introduction

Transgender is defined as identifying with a different gender than one's sex assigned at birth. Gender nonconformity is expressing oneself in ways that are not consistent with the societal norms for one's sex assigned at birth.1 Youth who identify as transgender and/or gender nonconforming (TGNC) might also meet criteria for gender dysphoria.2 Gender dysphoria is a term included within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) to describe the distress present in the context of incongruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity.2,3 While these terms are related, they are not interchangeable. Many, but not all, TGNC people experience gender dysphoria, and not all people who experience gender dysphoria identify as TGNC.

Across DSM editions preceding DSM-5, the American Psychiatric Association has classified the distress related to incongruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity in numerous ways. Because the criteria for gender dysphoria have not remained consistent over time and have pathologized the experience of transgender individuals, it is difficult to address co-occurring mental health issues with good validity. In DSM-IV,4 there was no requirement of distress related to incongruence of gender identity and sex assigned at birth. Instead, the diagnosis was called Gender Identity Disorder and required cross-sex identification, without focus on distress. It is now required within DSM-5 for children and adolescents to experience distress in addition to an incongruence between gender identity and sex assigned at birth to meet criteria for gender dysphoria. This asserts the idea that a transgender identity is not pathological and that distress can be functionally impairing.

Children and adolescents with gender dysphoria have a higher prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses, including social anxiety disorder, than those without gender dysphoria.5 Despite this higher prevalence, researchers have found that transgender youths who are supported by their parents have similar rates of mental health comorbidities to cisgender age matched peers.6 However, many transgender youths are not supported by their parents, and even among those who are supported, mental health comorbidities still exist, although at lower rates.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been shown to be effective treatment for social anxiety in children and adolescents.7,8 Furthermore, modifying CBT to a specific minority group is recommended as it is shown to increase the effectiveness of the treatment for that minority.9 One research group created a series of recommendations for a transgender affirming CBT approach which focuses on the effect of transphobia and increasing resilience in the population. They recommend focusing on feelings of hopelessness and experiences of discrimination and victimization.9

Despite these recommendations, there are no efficacy data on this technique. No formal guidelines have been published to direct providers in tailoring services for transgender youths who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria, despite the fact that 0.7% of teens aged 13–17 identify as transgender.10 To our knowledge, no study to date has assessed the efficacy of CBT for TGNC youth with co-occurring mental health disorders in addition to gender dysphoria. Despite TGNC youth comprising a large portion of our population, providers must rely on CBT-related research aimed to study sexual minorities, TGNC individuals. This article aims to review the current literature to provide a foundation for proposed modifications for CBT interventions for people with gender dysphoria and social anxiety. This article reviews mental health disparities for TGNC youth within the community, evidence for CBT for social anxiety disorder, and ways CBT has been recommended to be adapted in lesbian, gay and bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals.

Methods

Search strategy

The writers systematically reviewed peer reviewed literature related to cognitive behavioral interventions for youths and adults who experience gender dysphoria before July 2017. The literature search was conducted using three databases, including PubMed, PsycNET via Ovid, and Google Scholar. Search terms included “gender dysphoria AND social anxiety disorder AND children and adolescents,” “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy AND transgender,” and “transgender AND social anxiety disorder.” The search yielded few results. Because of this, the search was widened to include sexual minorities and TGNC people. Once these populations were included, the literature search yielded a variety of articles on related topics. The articles were then sorted into the sections of the literature review.

Selection

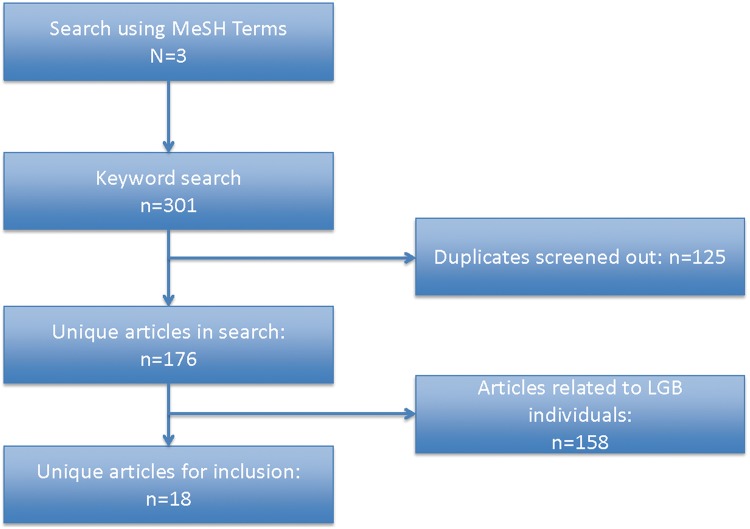

There were no articles using index terms or MeSH terms for “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy AND transgender,” “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy AND gender dysphoria,” “gender dysphoria AND social anxiety disorder,” and three articles for “transgender AND social anxiety.” None of the articles found through these searches focused on children. As such, we broadened our search using the keywords “cognitive behavioral therapy,” “transgender,” “gender dysphoria,” and “social anxiety disorder.” Through this search we found 176 unique articles and screened out 158 due to content related to LGB individuals and not transgender individuals, or not discussing social anxiety disorder specifically. We also did not assess literature related to voice therapies as it was out of the scope of this review. We did not assess literature that was not peer reviewed. A summary of the search strategy is depicted in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

Graphical depiction of search strategy and selection process.

Analysis

Each article was reviewed to assess: (1) the empirical research that has explored mental health disparities in transgender youth, specifically social anxiety, (2) treatment for social anxiety, specifically CBT, and (3) CBT techniques adapted for transgender individuals. There were few studies that address these issues and none that specifically address CBT for social anxiety disorder in transgender youth who meet criteria for gender dysphoria.

Results

Mental health disparities

TGNC people have higher prevalence rates of mental illnesses than the general population,11,12 including anxiety.13,14 Many researchers have hypothesized that this increased burden of mental illness stems from minority stress, which refers to the distress that may come from being a member of a marginalized or oppressed group.15–18 For TGNC individuals minority stress is experienced systemically through the chronic violence toward TGNC people, high rates of homelessness, underemployment, and poor medical care for these individuals. The majority of TGNC youth report social exclusion, parental rejection, and high levels of discrimination, bullying, and violence.19 These stressors have also been found to greatly impact sexual minority populations with cisgender gender identity and gender nonconforming gender expression.16,17

There are a few specific aspects of the minority stress theory that have been found to be associated with mental illness. One aspect, rejection sensitivity, describes the anxiety-causing expectations of rejection. Some literature suggests that rejection sensitivity is associated with a variety of internalizing pathology in gay and bisexual men.17 Another study found that childhood gender nonconformity was associated with anxiety in heterosexual and homosexual men, but not in heterosexual/homosexual women.20

Minority stress also places TGNC youth at risk for mental health concerns. There is literature assessing transgender adults, which states that rejection, self-stigma, and prejudice are related to psychological distress.21 Rates of mental health conditions in transgender adults vary greatly in the literature, although diagnoses span mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders22; however, most children and teens who meet criteria for gender dysphoria do not have a co-occurring mental health issue.5 In clinic referred youth, there is a high proportion of individuals with gender dysphoria seeking mental health services, although only 32.4% have at least one co-occurring mental health concern.5

More specifically, TGNC youth have rates of social anxiety disorder that reportedly range from 9.5% to 31.4%.2,5,23 Social anxiety disorder consists of anxiety specific to social situations where the possibility of being scrutinized by others exists and occurs in a variety of settings, including school, home, and social interactions.3 Social anxiety disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 12.1% in the United States and can result in impaired social, academic, and work performance.3,24 There is some dispute as to whether minority stress fully explains high rates of social anxiety. Bergero-Miguel et al. found that while gender dysphoria was significantly related to social anxiety disorder, only one variable related to minority stress, perceived violence at school, was significantly related to the disorder.2

Similarly, a study on sexual minorities found that people with sexual identities that were more marginalized, such as bisexuality, experienced higher rates of social anxiety disorder.25 This substantiates the assertion that transgender people experience higher rates of social anxiety disorder due to minority stress because while they face similar unfavorable life experiences as lesbian/gay/bisexual people, they also experience added distress because of their gender nonconformity and gender dysphoria.23 Overall, social anxiety disorder in relevant populations such as sexual and gender minorities has been hypothesized to be related to minority stress.5,23,25 We will next address evidence based treatments tailored to TGNC populations.

CBT for social anxiety disorder

Because of the high prevalence of social anxiety disorder within the TGNC/gender dysphoric populations, it is important to evaluate possible treatments for the disorder. CBT is an effective treatment for social anxiety that is a structured goal-based modality of therapy that utilizes a collection of therapeutic techniques.7,26–28 It focuses on being aware of and changing patterns of thought to change behaviors and emotions.7,26–28 Group CBT has been also cited as an efficacious way to treat social anxiety disorder in adults.29,30 One technique used in individual and group CBT that is especially useful for social anxiety disorder is exposure.

CBT is not only effective in the general population of adults but also is effective in children and adolescents.8 This is advantageous since social anxiety often starts during childhood and adolescence.3 Group treatment is especially helpful for those with social anxiety disorder because patients can practice their social skills with their peers in a supervised environment while also developing a social support network.7 These social skills are especially useful for children, since the majority of them have to socialize by necessity at school, while an adult can choose a career that does not involve as much social interaction. Group CBT has also been identified as efficacious in adolescents with social anxiety.31,32

There are several CBT techniques that are useful for social anxiety. For example, exposure is the gradual systematic process of putting individuals in contact with the things that make them anxious. Another technique used in CBT for social anxiety is learning cognitive strategies to restructure automatic negative thoughts.27 The goal is to direct negative thinking to neutral or more realistic thoughts. Most of the literature on CBT for social anxiety focuses on combating thought distortions that lead to the unreasonable fear that people will react to or evaluate an individual negatively.7,26–28 However, as previously established, transgender individuals have genuine fears that may not be addressed by cognitive restructuring, as there is a high probability of threat for rejection or even violence toward them. Many transgender youth are verbally harassed (54%) and physically assaulted (24%) while in school due to their transgender identity.33 Thus, traditional CBT methods must be modified to meet the realities and needs of this population.

Modified CBT/gender-affirming therapy

In 2015, the American Psychological Association published “Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People,” which endorsed trans-affirmative therapy. It outlined that trans-affirmative practice should be “respectful, aware, and supportive of the identities and life experiences of TGNC people” (p. 833).34 These guidelines call for practitioners to educate themselves on TGNC health, advocacy, and terminology and be validating and compassionate toward TGNC clients. Its reasoning is that TGNC people will have greater rates of improvement in clinical symptoms with trans-affirmative care (American Psychological Association, 2015).34 This has been shown in rates of suicidality and depression, but there is no clear evidence that it impacts anxiety as well.35

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) also published guidelines on how to treat TGNC individuals both from a mental health and medical standpoint.36 The mental health guidelines have several tenants, including being transparent and accepting toward clients, not imposing a binary view of gender onto them, and not attempting to change an individual's identity to cisgender. In addition, it emphasizes on educating clients about the resources available to them so that they can make informed decisions, as well as being an advocate and helping them advocate for themselves in their community. These guidelines were echoed by the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.37

Mizock and Lundquist add onto the American Psychological Association's (APA) guidelines by going over some of the possible missteps a mental health practitioner can make with transgender clients.38 These include placing the burden of education on the client instead of doing independent research, overlooking important aspects of the client's life unrelated to gender, and acting as gatekeeper to gender affirmative resources. Singh and Dickey call practitioners to action by elaborating on some of the tenants of the APA guidelines.39 They assert that professionals should develop cultural competence in the relevant intersectional identities of their clients in addition to their gender, assess their own gender relationships and possible biases, and use a strength-based approach to treatment.

Edwards-Leeper and Leibowitz expand on both the APA and WPATH sets of guidelines for affirmative therapy.40 They especially go into depth regarding TGNC children and adolescents, stating that supporting them can look different from supporting adults. This is because they are still developing their sense of identity and have more pressing family/social concerns than adults do, since they are in constant contact with their family and peers at school and home. In the face of these challenges, it is a practitioner's duty to support their client the best they can. While guidelines can help practitioners frame therapy services and treatment, it is also important to note that these guidelines do not have empirical support.

While it might not be ethical to randomize individuals to supportive versus nonsupportive treatment, there is no indication that practitioner support of a client's transgender identity in the setting of CBT improves social anxiety outcomes. Furthermore, measurement of individuals with social anxiety disorder has also been disputed in the literature due to nonstandardized demographic data collection. Johnson and Anderson conducted a systematic review of literature related to social anxiety treatment studies and found that while many of the studies assessed for gender, it is unclear whether they provided options for TGNC individuals.41 Shulman and Hope also reported the need for modifications for asking about gender in social anxiety measures. For example, asking about how an individual interacts with others of the “opposite sex” might be confusing for a TGNC individual. The researchers suggest using the language of “another gender.”42

To address this in a broader context, some researchers have indicated that individuals with gender dysphoria experience less social support, more psychopathology, and lower quality of life than those without gender dysphoria.43 While individual therapy for mental health issues in transgender individuals has not been studied systematically, two case studies regarding CBT treatment have been published: one about a cisgender male patient who identified as gay with depression44 and another about a transgender male with depression. Both case studies asserted the need for modification of treatment procedures to address stigma within the community.45 One limitation of these articles is that both are case studies and may not generalize to an entire population.

Another body of literature encompasses group therapy for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people, which might help combat social isolation and bolster social support. One group reviewed theoretical literature to form a group therapy support program for LGBTQ people seeking asylum. No outcome measures were used for this specific study.46 Heck, Croot, and Robohm piloted a psychotherapy group for transgender clients and summarized some of their advice for running such a group.47 Most of the suggestions were in line with and were included in the guidelines mentioned earlier, although some were specific to group therapy.

Like any group, practitioners and members need to establish trust in one another. With LGBTQ clients specifically, it is important not to force individuals to conform to society's or facilitators' ideas about gender and sexuality. Facilitators should also know their relative position, privilege, and lack of knowledge about LGBTQ issues if they do not identify as LGBTQ. Furthermore, the writers recommend that it is important to keep in mind that people know their own experience best. It should be noted that this is just a single pilot study with a small sample size, and further research needs to be done to establish empirical backing of these suggestions. In addition, this pilot study was process oriented and did not report outcome measures related to symptomatology. Therefore, we do not know if a group structured in the way of this study would generalize to transgender youth with gender dysphoria and co-occurring mental health issues. Another group focused on mental health resilience and was provided to LGBTQ individuals through Gay Straight Alliance clubs.48 Community support is overall associated with better mental health outcomes.49,50

Similarly, Austin and Craig published suggestions on how to practice gender affirmative CBT.9 CBT is yet to be studied empirically in transgender populations, so these are simply recommendations. However, they are still useful to consider as they have some backing in existing knowledge. Austin and Craig assert that professionals have bias and a lack of training around transgender people and the issues they face, which can lead to a lack of trust in the provider.9 The framework they give for trans-inclusive therapy includes explicitly disclosing that you are trans-inclusive, normalizing gender neutral language, validating a client's experiences and identity, and assessing transgender specific issues' impact on well-being. CBT should be tailored to deal with the specific minority stressors that transgender people face, such as bullying and discrimination. This can increase the efficacy of the treatment. Unfortunately, these recommendations are focused on the manner in which services are provided, but do not delineate specific skills or tenants that would be helpful in delivery of treatment.

Conclusions

Social anxiety disorder leads to impairment in day-to-day functioning, as well as a lower quality of life.3,24 People with gender dysphoria, including children and adolescents, have higher rates of social anxiety disorder than the general population.15–17 CBT has been found to be an effective treatment of social anxiety disorder.7,26–28 However, research shows that when working with marginalized groups, modifying the CBT to individual patients potentially makes it even more effective.9 Thus, it is imperative to tailor treatments for social anxiety to children and adolescents who also meet criteria for gender dysphoria; and, as there is no literature assessing whether CBT for TGNC youth is effective, it is important to study the efficacy of these adaptations. Unfortunately, tenants proposed by the professional community have not been studied through systematic research. This lack of empirical support does not provide mental health practitioners grounds to argue for an empirically supported treatment when working with children, adolescents, and their families.

While some studies have assessed the efficacy of CBT for sexual minorities, we do not know if these data apply to transgender youth who meet criteria for social anxiety disorder or transgender youth who meet criteria for social anxiety disorder and gender dysphoria. We recommend that researchers develop studies to determine whether CBT is efficacious for transgender youth who meet criteria for social anxiety or social anxiety and gender dysphoria. This research would further guide recommendations for the professional community.

Abbreviations Used

- APA

American Psychological Association

- CBT

cognitive behavioral therapy

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- LGBTQ

lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer

- TGNC

transgender and/or gender nonconforming

- WPATH

World Professional Association for Transgender Health

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Hanssmann C, Morrison D, Russian E. Talking, gawking, or getting it done: provider trainings to increase cultural and clinical competence for transgender and gender-nonconforming patients and clients. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2008;5:5–23 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergero-Miguel T, Garcia-Encinas MA, Villena-Jimena A, et al. Gender dysphoria and social anxiety: an exploratory study in Spain. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1270–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: Am Psychiatric Assoc., 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:1195–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e2015322–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher HM, Rabian BA, McCloskey MS. A brief group cognitive-behavioral intervention for social phobia in childhood. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18:459–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalid-Khan S, Santibanez M-P, McMicken C, Rynn MA. Social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatr Drugs. 2007;9:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin A, Craig SL. Transgender affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy: clinical considerations and applications. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46:2–1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman J, Flores A, Brown T, et al. Age of Individuals Who Identify as Transgender in the United States. Los Angeles: Williams Institute, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmel TC, Erickson-Schroth L. Mental health and the transgender population. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46:346–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, et al. Transgender and anxiety: a comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int J Transgenderism. 2017;18:16–26 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millet N, Longworth J, Arcelus J. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in the transgender population: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Transgenderism. 2016;18:27–38 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, et al. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:943–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puckett JA, Maroney MR, Levitt HM, Horne SG. Relations between gender expression, minority stress, and mental health in cisgender sexual minority women and men. Psychol Sex Orient Gend Divers. 2016;3:48–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen JM, Feinstein BA, Rodriguez-Seijas C, et al. Rejection sensitivity as a transdiagnostic risk factor for internalizing psychopathology among gay and bisexual men. Psychol Sex Orient Gend Diver. 2016;3:25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzman-Parra J, Paulino-Matos P, de Diego-Otero Y, et al. (2014). Substance use and social anxiety in transsexual individuals. J Dual Diagn. 10, 162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, et al. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: a respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:52–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippa RA. The relation between childhood gender nonconformity and adult masculinity–femininity and anxiety in heterosexual and homosexual men and women. Sex Roles. 2008;59:68–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timmins L, Rimes KA, Rahman Q. Minority stressors and psychological distress in transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2017;4:328–340 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gijs L, van der Putten-Bierman E, De Cuypere G. Psychiatric Comorbidity in adults with gender identity problems. In: Gender Dysphoria and Disorders of Sex Development: Progress in Care and Knowledge (Kreukels BPC, Steensma TD, de Vries ALC; eds). Boston, MA: Springer, 2014, pp. 255–276 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts KE, Schwartz D, Hart TA. Social anxiety among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. In: Social Anxiety in Adolescents and Young Adults. (Alfano CA, Beidel DC; eds). New York: American Psychological Association, 2011, pp. 161–181 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acarturk C, de Graaf R, Van Straten A, et al. Social phobia and number of social fears, and their association with comorbidity, health-related quality of life and help seeking. Soc Psychiatry psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadsworth LP, Hayes-Skelton SA. Differences among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual individuals and those who reported an other identity on an open-ended response on levels of social anxiety. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2015;2:18–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albano AM, DiBartolo PM. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Phobia in Adolescents: Stand Up, Speak Out. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martell CR, Safren SA, Prince SE. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies With Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Clients. New York: Guilford Press, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Follette WC, Darrow SM, Bonow JT. Cognitive behavior therapy: a current appraisal. General Principles and Empirically Supported Techniques of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (O'Donohue WT, Fisher JE; eds). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009, pp. 42–62 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heimberg RG, Barlow DH. New developments in cognitive-behavioral therapy for social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:21–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia: basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albano AM, Marten PA, Holt CS, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia in adolescents a preliminary study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayward C, Varady S, Albano AM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia in female adolescents: results of a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:721–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center For Transgender Equality, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Association AP. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70:832–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kattari SK, Walls NE, Speer SR, Kattari L. Exploring the relationship between transgender-inclusive providers and mental health outcomes among transgender/gender variant people. Social Work in Health Care. 2016;55:635–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WPATH TWPAfTH. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Seventh Version. World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011. Available at: www.wpath.org/site_page.cfm?pk_association_webpage_menu=1347&pk_association_webpage=3190 (last accessed February1, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boroughs MS, Feinstein BA, Mitchell AD, et al. Establishing priorities for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health disparities: Implications for intervention development, implementation, research, and practice. Behav Therapist. 2017;40:119–127 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizock L, Lundquist C. Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2016;3:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh AA. Implementing the APA guidelines on psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people: a call to action to the field of psychology. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2016;3:19–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edwards-Leeper L, Leibowitz S, Sangganjanavanich VF. Affirmative practice with transgender and gender nonconforming youth: expanding the model. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2016;3:16–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson SB, Anderson PL. Don't ask, don't tell: a systematic review of the extent to which participant characteristics are reported in social anxiety treatment studies. Anxiety Stress Coping Int J. 2016;29:589–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shulman GP, Hope DA. Putting our multicultural training into practice: assessing social anxiety disorder in sexual minorities. Behav Therapist. 2016;39:315–319 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davey A, Bouman WP, Arcelus J, Meyer C. Social support and psychological well-being in gender dysphoria: a comparison of patients with matched controls. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2976–2985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh K, Hope DA. LGB-affirmative cognitive behavioral treatment for social anxiety: a case study applying evidence-based practice principles. Cogn Behav Pract. 2010;17:56–65 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perry NS, Chaplo SD, Baucom KJW. The impact of cumulative minority stress on cognitive behavioral treatment with gender minority individuals: case study and clinical recommendations. Cogn Behav Pract. 2017;24:472–483 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reading R, Rubin LR. Advocacy and empowerment: Group therapy for LGBT asylum seekers. Traumatology. 2011;17:86–98 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heck NC, Croot LC, Robohm JS. Piloting a psychotherapy group for transgender clients: description and clinical considerations for practitioners. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2015;46:3–0. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heck NC. The potential to promote resilience: piloting a minority stress-informed, GSA-based, mental health promotion program for LGBTQ youth. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2015;2:225–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McConnell EA, Birkett MA, Mustanski B. Typologies of social support and associations with mental health outcomes among LGBT youth. LGBT Health. 2015;2:55–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pflum SR, Testa RJ, Balsam KF, et al. Social support, trans community connectedness, and mental health symptoms among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Divers. 2015;2:281–286 [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Busa S, Janssen A, Lakshman M (2018) A review of evidence based treatments for transgender youth diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, Transgender Health 3:1, 27–33, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0037.