Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccination is the most effective measure to prevent HBV infection. Routine HepB vaccination was recommended for infants in 1991 and catch-up vaccination has been recommended for adolescents since in 1995. The purpose of this study is to assess HepB vaccination among adolescents 13–17 years.

Methods

The 2006–2012 NIS-Teen were analyzed. Vaccination trends and coverage by birth cohort among adolescents were evaluated. Multivariable logistic regression and predictive marginal models are used to identify factors independently associated with HepB vaccination.

Results

HepB vaccination coverage increased from 81.3% in 2006 to 92.8% in 2012. Coverage varied by birth cohort and 79–83% received vaccination before 2 years of age for those who were born during 1995 and 1999. Among those who had not received vaccination by 11 years of age, for the 1993–1995 birth cohorts, 9–15% were vaccinated during ages 11–12 years, and 27–37% had been vaccinated through age 16 years. Coverage among adolescents 13–17 years in 2012 ranged by state from 84.4% in West Virginia to 98.7% in Florida (median 93.3%). Characteristics independently associated with a higher likelihood of HepB vaccination included living more than 5 times above poverty level, living in Northeastern or Southern region of the United States, and having a mixed facility as their vaccination provider. Those with a hospital listed as their vaccination provider and those who did not have a well-child visit at age 11–12 years were independently associated with a lower likelihood of HepB vaccination.

Conclusions

Efforts focused on groups with lower coverage may reduce disparities in coverage and prevent hepatitis B infection. Parents and providers should routinely review adolescent immunizations. Routine reminder/recall, expanded access in health care settings, and standing order programs should be incorporated into routine clinical care of adolescents.

Keywords: Hepatitis B vaccine, Vaccination, Coverage, Adolescent vaccination, The National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen)

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is transmitted by percutaneous or mucosal exposure to the blood or body fluids of an infected person. Among infants who acquire HBV infection at birth, as many as 90% remain chronically infected, whereas approximately 30–50% of children infected at age 1–5 years and 5% of healthy adults remain chronically infected [1,2]. An estimated 800,000–1.4 million persons in the United States live with chronic HBV infection; many are not aware of their infection [1–3].

Preventing HBV infection through vaccination is the most effective way to reduce HBV-related, life-long complications, reduce the reservoir of persons with chronic infection, and thereby eliminate HBV transmission. Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccines have proved safe, and approximately 95% effective at preventing HBV infection [1,2,4,5]. Protection induced by HepB vaccines has been monitored among populations for more than 22 years and remains high [6].

In 1981, HepB vaccine was first approved for use in the United States. In 1982, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended HepB vaccination for adults at increased risk for HBV infection [7]. In 1991, recognizing the difficulty of vaccinating high-risk adults and the substantial burden of HBV-related infections acquired from childhood infection (an estimated 30–50%) [1,2,8,9], the ACIP recommended children receive a HepB vaccine series starting in infancy [8]. It is important for children to receive HepB vaccination starting in infancy since sexual activity and risk behaviors may start in adolescence. Additionally, since adolescents and adults with risk behaviors may be difficult to identify, opportunities to offer vaccination are missed [8]. In 1995, ACIP recommended routine vaccination for all previously unvaccinated adolescents 11–12 years [10], and in 1999, the recommendations were broadened to include all previously unvaccinated children and adolescents 0–18 years.

Ensuring adolescents are vaccinated to protect against HBV infection has been an important public health concern since 1995 [11]. School immunization laws were modified in many states to reflect the new recommendations [12] and HepB vaccine coverage has been increasing among adolescents [13–15]. To reach the goal of eliminating HBV transmission in the United States and reduce the hepatitis B disease burden, high rates of protection among adolescents must be achieved for each adolescent cohort [1,2,16,17]. To determine the status of HepB coverage among adolescents 13–17 years in the United States, we used data from the 2006–2012 National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen). We also sought to identify factors independently associated with higher or lower vaccination coverage, and evaluate the extent of adolescent HepB vaccination catch-up.

2. Methods

The National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) was analyzed in 2014. The NIS-Teen is a national, random-digit-dialed (RDD) telephone survey sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The objective of the NIS-Teen is to provide timely, detailed information regarding vaccination among adolescents 13–17 years for vaccines recommended by the ACIP, including those given during childhood and during adolescence as catch up. The NIS-Teen is a two-phase survey. During the first phase, a telephone household interview is conducted to identify households with age-eligible adolescents. Initially, NIS-Teen only used a landline sample. However, beginning in 2011, the survey included landline and cellular telephone households [18,19]. After completing the household interview, consent is requested to contact the vaccination provider(s) to collect vaccination records.

The second phase of NIS-Teen is a Provider Record Check (PRC). An Immunization History Questionnaire is mailed to the vaccination provider to complete or to attach a copy of the vaccination record of the adolescent and mail back to the data collector. The questionnaire includes documented vaccinations for the adolescent, whether the adolescent had a well-child visit or check-up at the practice during ages 11–12 years, and selected characteristics of the provider and practice.

In 2012, the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) landline response rate was 55.1%. A total of 14,133 adolescents with provider-reported vaccination records were included, representing 62% of all adolescents from the landline sample with completed household interviews. The cellular-telephone sample CASRO response rate was 23.6%. A total of 5066 adolescents with provider-reported vaccination records were included, representing 56.4% of all adolescents from the cellular-telephone sample with completed household interviews. The overall sample size (landline and cellphone sample) was 19,199 [14]. Poverty status was defined using 2012 poverty thresholds published by the U.S. Census Bureau with below poverty defined as a total family income of <$23,492 for a family of four.

In the United States, there were two monovalent HepB vaccines for pediatric use (through age 18 years) and one combination vaccine available to adolescents who were 13–17 years in 2012. We used fully immunized as the outcome measure of HepB vaccination. Being fully immunized with HepB vaccine was defined as receipt of ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml of [1]: Engerix-B®, Recombivax HB®, or Comvax® [20], combinations of these three vaccines, or [2]: receipt of ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax HB® approved in 2000 as a two dose series for adolescents 11–15 years. Comvax® might have been available for infants born from 1996 to 1999, who are now adolescents 13–16 years. We assessed the association of the outcome measure with demographic and access to care characteristics. To assess missed opportunities, we evaluated the percentage of those who had not been fully vaccinated against hepatitis B by 11 years of age who had a vaccination visit, defined as those who had received a vaccination other than HepB during the period from their 11th year birthday through their age at interview (13–17 years).

SUDAAN (Software for the statistical analysis of complex sampling data, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) was used to calculate point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Weighting is adjusted to minimize non-response bias (e.g., to compensate for the non-coverage of teens in non-telephone households, a post-stratification adjustment is done based on whether the teen’s household experienced an interruption in telephone service). T-tests were used to examine associations with the significance level set at α< 0.05. Using combined data from 2006 to 2012, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was conducted to estimate, by birth cohort, the cumulative vaccination coverage by age overall, and among those who had not been vaccinated before their 11th year birthday (adolescent catch-up vaccination). To assess the independent effects of demographic and access-to-care variables on HepB vaccination, we conducted multivariable logistic regression and predictive marginal models which yielded adjusted prevalence difference (PD). The NIS-Teen was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board.

3. Results

A total of 19,199 adolescents 13–17 years with adequate provider data from the 2012 NIS-Teen were included in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 2012 sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of participants 13–17 years in the United States, by demographic and access-to-care variables–NIS-Teen, 2012.

| Characteristic | All adolescents | Vaccinateda | Not vaccinated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Sample (N) | Weighted % (95% CIc) | Sample | % (95% CI) | Sample | % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 19,199 | 17,869 | 1330 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 13–15 | 11,790 | 61.0 (59.7–62.3) | 11,048 | 61.3 (60.0–62.6) | 742 | 56.8 (51.8–61.7) |

| 16–17 | 7409 | 39.0 (37.7–40.3) | 6821 | 38.7 (37.4–40.0) | 588 | 43.2 (38.3–48.2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 10,141 | 51.2 (49.9–52.5) | 9448 | 51.1 (49.8–52.4) | 693 | 52.4 (47.3–57.4) |

| Female | 9058 | 48.8 (47.5–50.1) | 8421 | 48.9 (47.6–50.2) | 637 | 47.6 (42.6–52.7) |

| Race/ethnicitye | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 12,930 | 55.0 (53.7–56.2) | 12,079 | 55.5 (54.1–56.8) | 851 | 48.5 (43.5–53.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1928 | 14.1 (13.2–15.0) | 1801 | 14.0 (13.1–15.0) | 127 | 14.7 (11.1–19.1) |

| Hispanic | 2552 | 21.8 (20.6–23.0) | 2335 | 21.4 (20.1–22.7) | 217 | 27.0 (22.1–32.6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 261 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 253 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 8 | NA |

| Asian | 622 | 3.8 (3.3–4.5) | 559 | 3.8 (3.2–4.5) | 63 | 4.3 (2.6–6.9) |

| Other | 906 | 4.4 (3.9–4.9) | 842 | 4.3 (3.8–4.9) | 64 | 4.8 (3.2–7.2) |

| Mother’s educational level | ||||||

| <High School | 1874 | 14.0 (13.0–15.1) | 1715 | 13.7 (12.7–14.8) | 159 | 18.0 (13.9–22.9)g |

| High School | 3664 | 24.9 (23.7–26.1) | 3373 | 24.6 (23.4–25.8) | 291 | 28.2 (23.8–33.0) |

| Some college or college graduate | 5376 | 26.6 (25.5–27.8) | 4987 | 26.4 (25.3–27.6) | 389 | 29.3 (24.8–34.2) |

| >College graduate | 8285 | 34.5 (33.3–35.6) | 7794 | 35.2 (34.0–36.4) | 491 | 24.5 (21.1–28.4) |

| Mother’s married status | ||||||

| Married | 14,217 | 65.2 (63.9–66.5) | 13,278 | 65.6 (64.3–67.0) | 939 | 59.5 (54.1–64.6) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 3337 | 24.3 (23.1–25.5) | 3074 | 24.0 (22.8–25.3) | 263 | 27.6 (23.0–32.7) |

| Never married | 1477 | 10.6 (9.7–11.5) | 1367 | 10.4 (9.5–11.3) | 110 | 12.9 (9.3–17.7) |

| Mother’s age | ||||||

| ≤34 years | 1434 | 10.0 (9.1–10.9) | 1326 | 9.9 (9.0–10.9) | 108 | 10.9 (8.2–14.3) |

| 35–44 years | 7811 | 46.4 (45.1–47.7) | 7244 | 46.3 (45.0–47.7) | 567 | 46.9 (41.9–52.0) |

| ≥45 years | 9954 | 43.7 (42.4–44.9) | 9299 | 43.8 (42.5–45.1) | 655 | 42.2 (37.3–47.3) |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Born in U.S. | 18,469 | 94.7 (94.0–95.3) | 17,213 | 94.8 (94.0–95.4) | 1256 | 94.0 (91.6–95.7) |

| Born outside U.S. | 676 | 5.3 (4.7–6.0) | 605 | 5.2 (4.6–6.0) | 71 | 6.0 (4.3–8.4) |

| Income to poverty ratioh | ||||||

| <133% | 4502 | 35.7 (34.3–37.0) | 4117 | 35.0 (33.7–36.4) | 385 | 43.7 (38.7–48.9)g |

| 133–<322% | 5569 | 28.3 (27.2–29.5) | 5168 | 28.2 (27.0–29.4) | 401 | 30.1 (25.5–35.1) |

| 322–<503% | 4275 | 17.3 (16.4–18.1) | 4000 | 17.4 (16.6–18.3) | 275 | 15.4 (12.4–18.9) |

| >503% | 4853 | 18.8 (17.9–19.6) | 4584 | 19.4 (18.5–20.3) | 269 | 10.8 (8.9–13.1) |

| Medical insurance | ||||||

| Private Only | 9488 | 42.1 (40.9–43.4) | 8923 | 42.8 (41.5–44.0) | 565 | 34.0 (29.6–38.7)g |

| VFC Eligible-Medicaid/IHS/AIAN (All) | 7633 | 45.1 (43.8–46.4) | 7089 | 44.9 (43.5–46.2) | 544 | 47.7 (42.7–52.8) |

| VFC Eligible-Uninsured | 885 | 6.1 (5.4–6.8) | 782 | 6.0 (5.3–6.7) | 103 | 7.2 (5.1–10.0) |

| SCHIP (Public) | 554 | 3.7 (3.2–4.4) | 515 | 3.6 (3.0–4.2) | 39 | NA |

| Military | 497 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 430 | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | 67 | 4.4 (3.1–6.3) |

| Other | 142 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 130 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 12 | NA |

| Physician contacts within past year | ||||||

| None | 2963 | 17.4 (16.4–18.4) | 2689 | 17.1 (16.0–18.2) | 274 | 21.3 (17.7–25.5) |

| 1 | 5291 | 27.2 (26.0–28.3) | 4963 | 27.5 (26.3–28.8) | 328 | 22.4 (18.4–27.1) |

| 2–3 | 6803 | 35.5 (34.3–36.7) | 6342 | 35.4 (34.1–36.6) | 461 | 37.3 (32.4–42.6) |

| ≥4 | 4034 | 19.9 (19.0–21.0) | 3775 | 20.0 (19.0–21.1) | 259 | 18.9 (15.7–22.7) |

| Well child visit at age 11–12 yearsi | ||||||

| Yes | 8482 | 41.8 (40.6–43.1) | 8144 | 43.2 (41.9–44.5) | 338 | 23.4 (19.7–27.6)g |

| No | 5373 | 28.0 (26.9–29.2) | 4976 | 27.9 (26.7–29.1) | 397 | 30.3 (25.9–35.1) |

| Do not know | 5344 | 30.1 (29.0–31.4) | 4749 | 28.9 (27.7–30.1) | 595 | 46.3 (41.2–51.4) |

| Number of vaccination providers | ||||||

| 1 | 8964 | 47.5 (46.2–48.7) | 8332 | 47.5 (46.1–48.8) | 632 | 47.5 (42.5–52.6) |

| 2 | 5918 | 30.4 (29.2–31.6) | 5509 | 30.3 (29.1–31.6) | 409 | 31.7 (27.4–36.4) |

| ≥3 | 4303 | 22.1 (21.1–23.2) | 4028 | 22.2 (21.1–23.4) | 275 | 20.8 (16.6–25.6) |

| MSA | ||||||

| Urban area | 7428 | 39.1 (37.9–40.4) | 6876 | 39.0 (37.8–40.3) | 552 | 40.7 (35.8–45.9) |

| Suburban area | 7552 | 45.6 (44.3–46.9) | 7077 | 45.7 (44.4–47.0) | 475 | 43.8 (38.8–48.9) |

| Rural area | 4219 | 15.3 (14.5–16.0) | 3916 | 15.3 (14.5–16.1) | 303 | 15.5 (12.8–18.5) |

| Regionb | ||||||

| Northeast | 3614 | 17.0 (16.5–17.5) | 3455 | 17.5 (16.9–18.0) | 159 | 11.1 (8.8–14.0)g |

| Midwest | 4204 | 21.8 (21.2–22.4) | 3909 | 21.5 (20.8–22.2) | 295 | 25.6 (21.7–30.0) |

| South | 6844 | 37.1 (36.3–37.9) | 6368 | 37.5 (36.6–38.3) | 476 | 32.8 (28.7–37.2) |

| West | 4537 | 24.1 (23.2–24.9) | 4137 | 23.6 (22.7–24.5) | 400 | 30.4 (25.4–35.9) |

| Facility type | ||||||

| All private facilities | 9309 | 51.6 (50.3–52.9) | 8695 | 51.9 (50.6–53.3) | 614 | 46.8 (41.7–51.9)g |

| All public facilities | 2720 | 15.1 (14.1–16.1) | 2524 | 14.8 (13.8–15.8) | 196 | 19.0 (14.8–24.1) |

| All hospital facilities | 1771 | 7.5 (6.9–8.2) | 1564 | 7.0 (6.4–7.7) | 207 | 14.6 (11.6–18.1) |

| All STD/school/teen clinics or other facilities | 235 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 209 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 26 | NA |

| Mixedd | 4918 | 23.7 (22.6–24.8) | 4730 | 24.4 (23.3–25.5) | 188 | 14.2 (11.0–18.2) |

| Otherf | 189 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 147 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 42 | 2.9 (1.8–4.6) |

Being fully immunized with Hepatitis B vaccine includes either received ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml Engerix® or Recombivax® or Comvax® vaccine or ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax® vaccine.

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Confidence interval.

Mixed indicates that the facility is identified to be in more than one of the facility categories such as private, public, hospital, STD/school/teen clinics.

Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and other race (including multiple races).

Includes military, WIC clinics, and pharmacies.

Significant difference between those who received vaccination and those who did not (by chi-square test, p < 0.05).

We calculated the federal poverty level (PVL) by using the reported household income and the 2012 federal PVL thresholds defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Status of health-care visit at age 11–12 years based on provider reported data.

Among adolescents 13–17 years, overall HepB coverage was 92.8% (95% confidence interval (CI = 92.1–93.5%) in 2012 (Table 2). Vaccination coverage was similar by age group and sex. Hispanics had significantly lower coverage (91.1%) compared to non-Hispanic whites (93.7%). Adolescents with a mother who had more than a college degree (94.9%) were significantly more likely to receive HepB vaccination than those with a mother who had less than high school education (90.8%) (p < 0.05). HepB vaccination coverage was significantly higher among adolescents living in a household with 3–5 times above poverty level (93.6%) (p = 0.02) or more than 5 times above poverty level (95.9%) compared with those living below the poverty level (91.2%) (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hepatitis B vaccination coverage and multivariable logistic regression analysis among adolescents 13–17 years in the United States, by demographic and access-to-care characteristics – NIS-Teen 2012.

| Characteristic | Hepatitis B vaccination coveragea | Prevalence Difference (PD) (adjusted) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| % (95% CI) | p-Value† | % (95% CI) | p-Value‡ | |

| Total | 92.8 (92.1–93.5) | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 13–15c | 93.3 (92.3–94.2) | Ref. | ||

| 16–17 | 92.1 (90.9–93.1) | 0.08 | −1.0 (−2.5 to 0.4) | 0.15 |

| Sex | ||||

| Malec | 92.7 (91.6–93.6) | |||

| Female | 93.0 (92.0–93.9) | 0.63 | 0.3 (−1.0 to 1.6) | 0.69 |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Whitec | 93.7 (92.9–94.3) | Ref. | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 92.5 (90.1–94.4) | 0.31 | −0.2 (−2.8 to 2.4) | 0.88 |

| Hispanic | 91.1 (88.8–93.0) | 0.02 | −1.1 (−3.3 to 1.1) | 0.33 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 94.1 (84.8–97.9) | 0.88 | 0.7 (−5.1 to 6.5) | 0.81 |

| Asian | 92.0 (87.3–95.1) | 0.41 | −1.8 (−5.7 to 2.1) | 0.37 |

| Other | 92.1 (88.4–94.8) | 0.35 | −1.5 (−4.8 to 1.9) | 0.39 |

| Mother’s educational level | ||||

| <High Schoolc | 90.8 (88.0–93.0) | Ref. | ||

| High School | 91.9 (90.2–93.3) | 0.48 | −0.0 (−2.5 to 2.4) | 0.98 |

| Some college or college graduate | 92.1 (90.5–93.5) | 0.38 | −0.0 (−2.6 to 2.6) | 0.98 |

| >College graduate | 94.9 (94.1–95.6) | <0.01 | 1.7 (−0.9 to 4.3) | 0.20 |

| Mother’s married status | ||||

| Marriedc | 93.5 (92.7–94.2) | Ref. | ||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 91.9 (90.0–93.4) | 0.08 | −0.7 (−2.6 to 1.1) | 0.43 |

| Never married | 91.3 (87.8–93.8) | 0.15 | −1.1 (−4.3 to 2.1) | 0.49 |

| Mother’s age | ||||

| ≤34 yearsc | 92.2 (89.6–94.2) | Ref. | ||

| 35–44 years | 92.7 (91.6–93.7) | 0.66 | 0.2 (−2.0 to 2.4) | 0.87 |

| ≥45 years | 93.1 (92.0–94.0) | 0.49 | −1.1 (−3.6 to 1.5) | 0.42 |

| Immigration status | ||||

| Born in U.S.c | 92.9 (92.1–93.6) | Ref. | ||

| Born outside U.S. | 91.8 (88.6–94.2) | −0.2 (−2.9 to 2.6) | 0.91 | |

| Income to poverty ratioe | ||||

| <133%c | 91.2 (89.7–92.5) | Ref. | ||

| 133–<322% | 92.4 (90.8–93.7) | 0.25 | 0.7 (−1.3 to 2.8) | 0.50 |

| 322–<503% | 93.6 (92.1–94.8) | 0.02 | 0.8 (−1.7 to 3.4) | 0.53 |

| >503% | 95.9 (95.0–96.6) | <0.01 | 3.2 (1.0–5.3) | <0.01 |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Private Onlyc | 94.2 (93.3–95.0) | Ref. | ||

| VFC Eligible-Medicaid/IHS/AIAN (All) | 92.4 (91.2–93.4) | 0.07 | 0.1 (−1.7 to 1.9) | 0.89 |

| VFC Eligible-Uninsured | 91.5 (88.2–93.9) | 0.55 | 0.1 (−2.6 to 2.8) | 0.94 |

| SCHIP (Public) | 89.5 (81.1–94.4) | 0.59 | −2.7 (−8.6 to 3.2) | 0.36 |

| Military | 85.0 (79.2–89.4) | 0.03 | −4.9 (−10.8 to 1.0) | 0.11 |

| Other | 90.4 (79.5–95.8) | 0.79 | −2.2 (−10.2 to 5.7) | 0.58 |

| Physician contacts within past year | ||||

| Nonec | 91.2 (89.3–92.7) | Ref. | ||

| 1 | 94.1 (92.7–95.2) | 0.01 | 1.6 (−0.4 to 3.5) | 0.11 |

| 2–3 | 92.4 (91.0–93.7) | 0.08 | −0.1 (−2.2 to 1.9) | 0.89 |

| ≥4 | 93.2 (91.8–94.4) | 0.34 | 0.4 (−1.6 to 2.4) | 0.66 |

| Well-child visit at age 11–12 years | ||||

| Yesc | 96.0 (95.2–96.6) | Ref. | ||

| No | 92.2 (90.8–93.5) | <0.01 | −3.3 (−5.1 to 1.6) | <0.01 |

| Do not know | 89.0 (87.2–90.5) | <0.01 | −4.8 (−6.5 to 3.0) | <0.01 |

| Number of vaccination provider | ||||

| 1 | 92.9 (91.8–93.8) | 0.71 | 1.0 (−1.3 to 3.2) | 0.38 |

| 2 | 92.6 (91.3–93.7) | 0.64 | −0.3 (−2.4 to 1.8) | 0.79 |

| ≥3c | 93.3 (91.5–94.8) | Ref. | ||

| MSA | ||||

| Urban area | 92.5 (91.3–93.6) | 0.83 | 0.2 (−1.7 to 2.0) | 0.86 |

| Suburban area | 93.1 (92.0–94.1) | 0.66 | 0.1 (−1.7 to 1.8) | 0.94 |

| Rural areac | 92.7 (91.3–93.9) | Ref. | ||

| Regionb | ||||

| Northeast | 95.3 (94.1–96.3) | <0.01 | 3.4 (1.2 to 5.6) | <0.01 |

| Midwest | 91.6 (89.9–93.0) | 0.61 | 0.5 (−2.0 to 2.9) | 0.71 |

| South | 93.7 (92.7–94.5) | 0.01 | 2.3 (0.1 to 4.4) | <0.01 |

| Westc | 90.9 (88.7–92.7) | Ref. | ||

| Facility type | ||||

| All private facilitiesc | 93.7 (92.7–94.5) | Ref. | ||

| All public facilities | 91.2 (88.6–93.3) | 0.05 | 0.5 (−2.1 to 3.1) | 0.71 |

| All hospital facilities | 86.5 (83.3–89.2) | <0.01 | −4.6 (−7.6 to 1.6) | <0.01 |

| All STD/school/teen clinics or other facilities | 86.9 (77.4–92.8) | 0.08 | −2.9 (−9.1 to 3.4) | 0.37 |

| Mixedf | 95.8 (94.5–96.8) | <0.01 | 3.7 (1.8 to 5.5) | <0.01 |

| Otherg | 73.8 (60.4–83.9) | <0.01 | −10.4 (−22.0 to 1.1) | 0.08 |

p Value by t test for comparisons within each variable with the indicated reference level.

p Value by t test for comparisons within each variable with the indicated reference level based on multivariable logistic model.

Being fully immunized with Hepatitis B vaccine includes either received ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml Engerix® or Recombivax® or Comvax® vaccine or ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax® vaccine.

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia; West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Reference level.

Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and other race (including multiple races).

We calculated the federal poverty level (PVL) by using the reported household income and the 2012 federal PVL thresholds defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Mixed indicates that the facility is identified to be in more than one of the facility categories such as private, public, hospital, STD/school/teen clinics.

Includes military, WIC clinics, and pharmacies.

Adolescents with military medical insurance (85.0%) were significantly less likely to receive HepB vaccination than those with private medical insurance (94.2%) (p = 0.03). HepB vaccination coverage was significantly higher among those with one physician contact (94.1%) compared to those who had no physician contacts in the past year (91.2%) (p = 0.01). Adolescents who did not have a well-child visit at ages 11–12 years (based on provider reported data) were significantly less likely to obtain vaccination (92.2%) than those who had a visit (96.0%) (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

HepB vaccination coverage varied by region of residence; it was significantly higher among persons who lived in the Northeast (95.3%) and the South (93.7%) than those who lived in the West (90.9%) (p < 0.01, p = 0.01, respectively). Adolescents who received vaccinations at facilities such as hospital and “other” facilities (coverage was 86.5%, and 73.8%, respectively) were significantly less likely to be vaccinated with HepB than those who received vaccinations at private facilities (93.7%) (p < 0.01). Adolescents who received vaccinations at mixed facilities (95.8%) were significantly more likely to be vaccinated with HepB than those who received vaccinations at private facilities (93.7%) (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Multivariable logistic regression modeling and predictive marginal analysis were conducted using the 2012 data to identify factors independently associated with HepB vaccination among adolescents 13–17 years (Table 2). Characteristics independently associated with a higher likelihood of HepB vaccination included: living more than 5 times above the poverty level compared with living below the poverty level (PD = 3.2), living in the Northeastern (PD = 3.4) or the Southern region (PD = 2.3) of the United States compared with those living in the West, and having a mixed facility as their vaccination provider compared with a private facility (PD = 3.7). Adolescents with a hospital (PD = −4.6) or “other” facility (PD = −10.4) listed as their vaccination provider compared with a private facility and those who did not have a well-child visit at ages 11–12 years (PD = −3.3) compared with those who had a well-child visit at ages 11–12 years were independently associated with a lower likelihood of HepB vaccination (Table 2). Race/ethnicity, mother’s educational level, and number of physician contacts within the past year were significant in the bi-variable analysis but were no longer significant in the multivariable model.

Overall, vaccination coverage by state ranged from 84.4% in West Virginia to 98.7% in Florida, with a median across all states of 93.3% (Table 3). Coverage before 11 years of age by state ranged from 81.1% in West Virginia to 96.9% in New Hampshire, with a median of 91.3%. Catch-up vaccination proportion after 11 years of age by state ranged from 0.0% in Kentucky and Ohio to 78.3% in Florida, with a median of 24.6% (Table 3). The proportion of adolescents not fully vaccinated before age 11 years who were subsequently vaccinated ranged from 0.0% to 78.2% (median 24.6%). The median catch-up vaccination proportion at or after 11 years of age among states with HepB vaccination middle school requirements was 22.5% compared to 19.4% among states without HepB vaccination middle school requirements.

Table 3.

Hepatitis B vaccination coverage of adolescents aged 13–17 years by state, NIS-Teen 2012.

| Sample size | Vaccination coveragea | Vaccination coverage before 11 years of agea | Proportion vaccinated at or after 11 years of agea,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| National | 19,199 | 92.8 (92.1–93.5) | 90.6 (89.8–91.4) | 23.4 |

| Alabama | 317 | 96.4 (93.8–97.9) | 95.1 (91.9–97.1) | 26.5 |

| Alaska | 340 | 91.1 (87.2–93.9) | 88.8 (84.5–92.1) | 20.5 |

| Arizona | 360 | 84.5 (78.2–89.2) | 83.5 (77.2–88.3) | 6.1 |

| Arkansas | 322 | 92.6 (88.5–95.3) | 90.4 (85.6–93.7) | 22.9 |

| California | 430 | 92.4 (88.1–95.2) | 90.3 (85.4–93.7) | 21.6 |

| Colorado | 311 | 96.4 (93.7–98.0) | 95.5 (92.3–97.4) | 20.0 |

| Connecticut | 323 | 95.7 (92.0–97.8) | 94.5 (90.4–96.9) | 21.8 |

| Delaware | 341 | 94.8 (90.9–97.0) | 91.7 (86.7–94.9) | 37.3 |

| District of Columbia | 342 | 92.7 (86.8–96.1) | 89.9 (83.4–94.0) | 27.7 |

| Florida | 325 | 98.7 (96.5–99.5) | 94.0 (87.1–97.3) | 78.3 |

| Georgiac | 328 | 97.1 (92.8–98.9) | 94.7 (88.8–97.6) | 45.3 |

| Hawaii | 342 | 92.3 (88.0–95.2) | 90.2 (85.1–93.7) | 21.4 |

| Idaho | 357 | 91.1 (86.8–94.0) | 88.7 (83.7–92.4) | 21.2 |

| Illinois | 632 | 90.7 (85.6–94.0) | 89.2 (84.0–92.9) | 13.9 |

| Indiana | 341 | 94.9 (90.5–97.3) | 93.9 (89.1–96.6) | 16.4 |

| Iowac | 325 | 93.8 (89.4–96.4) | 92.0 (86.7–95.3) | 22.5 |

| Kansas | 340 | 91.3 (85.9–94.7) | 88.4 (82.8–92.3) | 25.0 |

| Kentucky | 333 | 95.0 (91.3–97.1) | 95.0 (91.3–97.1) | 0.0 |

| Louisiana | 370 | 95.6 (92.1–97.6) | 94.1 (90.2–96.5) | 25.4 |

| Mainec | 319 | 93.6 (89.7–96.1) | 90.8 (86.3–93.9) | 30.4 |

| Maryland | 325 | 94.5 (89.9–97.1) | 93.5 (88.9–96.2) | 15.4 |

| Massachusetts | 347 | 95.9 (91.7–98.0) | 92.5 (87.8–95.5) | 45.3 |

| Michigan | 368 | 93.3 (88.6–96.2) | 92.5 (87.8–95.5) | 10.7 |

| Minnesota | 322 | 94.1 (90.4–96.5) | 91.5 (86.6–94.7) | 30.6 |

| Mississippic | 321 | 93.5 (87.3–96.8) | 92.9 (86.8–96.3) | 8.5 |

| Missouri | 292 | 87.9 (82.1–92.0) | 85.9 (79.3–90.7) | 14.2 |

| Montanac | 325 | 89.8 (85.4–92.9) | 89.1 (84.7–92.3) | 6.4 |

| Nebraska | 328 | 90.0 (84.5–93.7) | 88.6 (83.1–92.5) | 12.3 |

| Nevadac | 329 | 90.5 (85.8–93.8) | 87.4 (81.3–91.7) | 24.6 |

| New Hampshire | 278 | 97.3 (94.6–98.7) | 96.9 (94.0–98.4) | 12.9 |

| New Jersey | 330 | 96.9 (93.4–98.6) | 94.7 (90.1–97.3) | 41.5 |

| New Mexico | 331 | 89.9 (85.3–93.3) | 85.5 (79.4–90.0) | 30.3 |

| New York | 627 | 94.6 (92.0–96.4) | 91.4 (88.5–93.7) | 37.2 |

| North Carolina | 347 | 95.6 (92.0–97.6) | 92.9 (88.1–95.9) | 38.0 |

| North Dakotac | 324 | 91.2 (85.1–95.0) | 88.8 (82.1–93.1) | 21.4 |

| Ohio | 327 | 88.4 (81.9–92.8) | 88.4 (81.9–92.8) | 0.0 |

| Oklahoma | 322 | 95.0 (91.9–96.9) | 93.3 (89.6–95.7) | 25.4 |

| Oregon | 381 | 92.7 (88.9–95.2) | 91.5 (87.7–94.3) | 14.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 741 | 94.8 (91.7–96.8) | 93.1 (89.5–95.5) | 24.6 |

| Rhode Island | 327 | 94.3 (89.5–97.0) | 91.5 (86.3–94.8) | 32.9 |

| South Carolina | 310 | 92.9 (88.1–95.9) | 92.8 (88.1–95.8) | 1.4 |

| South Dakotac | 298 | 90.3 (85.4–93.6) | 88.3 (83.1–92.1) | 17.1 |

| Tennessee | 331 | 96.2 (93.2–97.9) | 94.3 (90.0–96.8) | 33.3 |

| Texas | 1594 | 87.6 (84.6–90.1) | 84.1 (80.8–86.9) | 22.0 |

| Utahc | 345 | 85.5 (79.6–89.9) | 84.8 (78.8–89.3) | 4.6 |

| Vermont | 322 | 93.4 (88.7–96.3) | 90.8 (86.0–94.1) | 28.3 |

| Virginia | 334 | 92.7 (88.1–95.5) | 90.3 (84.6–94.0) | 24.7 |

| Washington | 353 | 86.5 (80.2–91.0) | 83.3 (76.5–88.3) | 19.2 |

| West Virginiac | 282 | 84.4 (77.6–89.4) | 81.1 (73.6–86.9) | 17.5 |

| Wisconsin | 307 | 94.1 (91.0–96.2) | 91.2 (86.5–94.3) | 33.0 |

| Wyoming | 333 | 94.5 (91.0–96.7) | 93.7 (89.9–96.2) | 12.7 |

| Median | 93.3 | 91.3 | 24.6 | |

| Range | 84.4–98.7 | 81.1–96.9 | 0.0–78.3 |

Being fully immunized with Hepatitis B vaccine includes either received ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml Engerix® or Recombivax® vaccine or ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax® vaccine.

Proportion vaccinated after turning 11 years of age among those not fully vaccinated against HepB vaccination before 11 years of age.

Indicate that states without middle school HepB vaccination requirement.

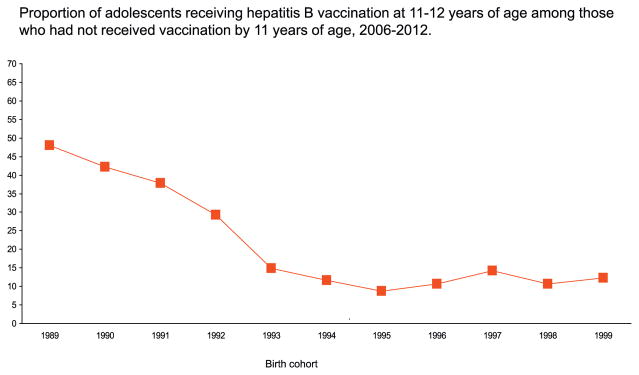

Tables 4–5 and Figs. 1–3 are based on the combined 2006–12 data. Sample sizes for 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011 were 1882, 2947, 17,835, 20,066, 19,257, 23,564, respectively. Among adolescents born during 1995–1999, 79–83% had been fully vaccinated before two years of age, 85–89% had been fully vaccinated before five years of age, and 90–93% had been fully vaccinated before 11 years of age (Table 4). Among those born during 1993–1995 who had not been vaccinated before 11 years of age, adolescent catch-up vaccination coverage was 9–15% during ages 11–12 years, and increased for each birth cohort for later ages, reaching 27–37% before age 17 years. For all ages of receipt, adolescent catch-up coverage has declined from the earliest to the most recent birth cohorts. For the most recent cohort followed to age 17 years (born in 1995, or turned 11 in 2006), catch-up coverage was 27% (Table 5). Adolescent catch-up coverage during ages 11–12 years declined from 48% among those born in 1989 to 29% among those born in 1992, and ranged from 9 to 15% among those born during 1993–1999 (Fig. 1, Table 5).

Table 4.

Cumulative percent receiving full Hepatitis B vaccinationa by age and birth cohort, adolescents aged 13–17 years, NIS-Teen 2006–2012.

| Birth cohort | Age in years | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| <1 | <2 | <3 | <4 | <5 | <6 | <7 | <8 | <9 | <10 | <11 | <12 | <13 | <14 | <15 | <16 | <17 | |

| 1989 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 6.4 | 11.6 | 13.8 | 18.2 | 25.1 | 31.3 | 39.8 | 51.9 | 68.5 | 73.4 | 75.8 | 76.9 | 78.1 |

| 1990 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 5.5 | 9.5 | 12.6 | 17.5 | 21.0 | 26.1 | 32.3 | 39.7 | 49.7 | 59.1 | 70.9 | 75.5 | 77.6 | 79.3 | 80.5 |

| 1991 | 1.2 | 7.1 | 12.1 | 14.5 | 19.6 | 27.7 | 35.6 | 41.0 | 45.9 | 51.9 | 57.1 | 64.4 | 73.3 | 77.3 | 79.3 | 81.6 | 82.6 |

| 1992 | 23.0 | 38.0 | 42.5 | 46.0 | 53.1 | 63.4 | 68.1 | 70.6 | 72.9 | 74.9 | 77.3 | 80.9 | 83.9 | 85.0 | 86.1 | 86.8 | 87.6 |

| 1993 | 52.3 | 66.7 | 70.4 | 73.6 | 76.9 | 81.5 | 83.1 | 84.0 | 85.0 | 85.4 | 86.4 | 87.6 | 88.4 | 89.1 | 89.7 | 90.3 | 90.8 |

| 1994 | 61.3 | 74.6 | 78.4 | 80.9 | 83.1 | 85.5 | 86.6 | 87.2 | 87.8 | 88.3 | 88.9 | 89.4 | 90.2 | 90.6 | 91.0 | 91.7 | 93.0 |

| 1995 | 66.7 | 79.2 | 81.7 | 83.6 | 85.5 | 87.6 | 88.6 | 89.0 | 89.34 | 89.9 | 90.5 | 91.0 | 91.3 | 91.8 | 92.1 | 92.7 | 93.1 |

| 1996 | 71.3 | 82.4 | 85.1 | 86.6 | 88.0 | 89.3 | 89.9 | 90.1 | 90.3 | 90.7 | 91.1 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92.6 | 92.8 | 93.3 | |

| 1997 | 71.4 | 83.3 | 85.3 | 86.9 | 88.1 | 89.5 | 90.5 | 90.9 | 91.3 | 91.7 | 92.5 | 93.1 | 93.6 | 93.8 | 94.2 | ||

| 1998 | 70.7 | 83.3 | 85.5 | 87.0 | 88.8 | 90.0 | 90.5 | 91.1 | 91.4 | 91.6 | 92.4 | 92.9 | 93.2 | 93.5 | |||

| 1999 | 56.0 | 81.7 | 85.1 | 87.3 | 89.0 | 90.1 | 90.4 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 91.1 | 91.5 | 91.8 | 92.4 | ||||

Being fully immunized with Hepatitis B vaccine includes either received ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml Engerix® or Recombivax® vaccine or ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax® vaccine. The standard errors for the estimates ranged from 0.2 to 2.6.

Table 5.

Cumulative percent receiving full Hepatitis B adolescent catch-up vaccinationa by age and birth cohort, among adolescents aged 13–17 years who had not received full HepB vaccination before age 11 years, NIS-Teen 2006–2012.

| Birth cohort | Indicate that vaccinations are counted if received on or after the 11th birthdaya | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| <12 | <13 | <14 | <15 | <16 | <17 | |

| 1989 | 20.5 | 48.0 | 56.1 | 60.1 | 61.9 | 63.8 |

| 1990 | 18.7 | 42.2 | 51.4 | 55.5 | 58.9 | 61.3 |

| 1991 | 17.1 | 37.8 | 47.3 | 51.8 | 57.1 | 59.6 |

| 1992 | 15.9 | 29.3 | 33.9 | 39.0 | 42.1 | 45.3 |

| 1993 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 19.7 | 23.8 | 28.5 | 32.2 |

| 1994 | 4.8 | 11.7 | 15.7 | 19.5 | 25.4 | 37.2 |

| 1995 | 5.8 | 8.8 | 13.6 | 16.8 | 23.1 | 27.4 |

| 1996 | 4.0 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 19.1 | 24.1 | |

| 1997 | 7.9 | 14.3 | 17.6 | 22.8 | ||

| 1998 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 15.0 | |||

| 1999 | 4.9 | 12.3 | ||||

Being fully immunized with Hepatitis B vaccine includes either received ≥3 doses of 0.5 ml Engerix® or Recombivax® vaccine or ≥2 doses of 1.0 ml of Recombivax® vaccine. The standard errors for the estimates ranged from 0.8 to 4.6.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of adolescents receiving hepatitis B vaccination at 11–12 years of age among those who had not received vaccination by 11 years of age, 2006–2012.

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2006–2012.

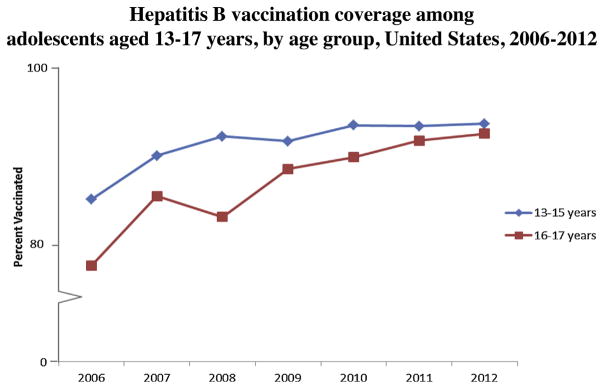

Fig. 3.

Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years, by age group, United States, 2006–2012.

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006–2012.

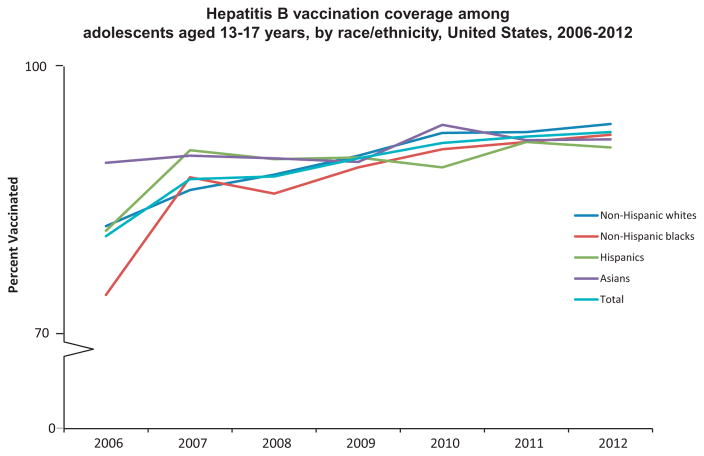

Overall, HepB vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years significantly increased from 81.3% in 2006 to 92.8% in 2012 (test for trend, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2), with an average 2.0 percentage point increase annually. Coverage among non-Hispanic whites significantly increased from 82.4% in 2006 to 93.7% in 2012 (test for trend, p < 0.05), and coverage among non-Hispanic blacks significantly increased from 74.8% in 2006 to 92.5% in 2012 (test for trend, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). HepB vaccination coverage did not change significantly between 2006 and 2012 for Hispanics and Asians (Fig. 2). Numbers were too small to examine trends for American Indians/Alaskan Natives. Coverage for adolescents 13–15 years significantly increased from 84.3% in 2006 to 93.3% in 2012 (test for trend, p < 0.05), and coverage for adolescents 16–17 years increased from 76.4% in 2006 to 92.1% in 2012 (test for trend, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years, by race/ethnicity, United States, 2006–2012.

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006–2012.

Among those not fully vaccinated against HepB vaccination in the 2012 NIS-Teen sample, 59.5% did not receive any dose, 15.4% received 1 dose, and 25.1% received 2 doses of HepB vaccination. Among those not fully vaccinated against HepB vaccination, overall, 78.0% had at least one vaccination visit (received a vaccination other than HepB), and 22.0% did not have any vaccination visits. Among those who did not receive any dose of HepB, overall, 85.2% had at least one vaccination visit. Among those who received one dose of HepB, overall, 56.7% had at least one vaccination visit. Among those who received two doses of HepB, overall, 74.3% had at least one vaccination visit.

4. Discussion

Our study using the NIS-Teen showed that 93% of adolescents 13–17 years in the United States in 2012 were fully vaccinated against hepatitis B, an increase of 12 percentage points compared to 2006 [13,15]. Among adolescents aged 13–17 years in 2012 (born 1995–1999), the percentage with completed HepB vaccination was 79–83% before age two years, 85–89% before five years of age, and 90–93% before age 11 years. Thus, a large proportion of the high HepB vaccination coverage among adolescents was likely due to ACIP recommendations for universal infant vaccination in 1991 and well-established childhood vaccination programs, decreasing the need for vaccination later in childhood or adolescence [8]. HepB vaccination “catch-up” recommendations in 1995 and 1999 contributed to the resulting HepB coverage above 90% for cohorts born from 1996 to 1999 [10,12,15]. Among adolescents who had not received the full HepB vaccination by 11 years of age, the proportion who received catch-up HepB vaccination during ages 11–12 years was low (9–15%) for the most recently measured cohorts (those turning age 11 years during 2004–2010). HepB catch-up vaccination coverage increased with age but remained low (27–37%) by age 17 years for the most recent cohorts followed to age 17 (those turning 11 years during 2004–2006).

Gaps may not be apparent when coverage is at a high level. Despite the substantial gains in HepB vaccination, 7.2% of adolescents 13–17 years had not received a complete HepB vaccination series in 2012. Studies have reported racial/ethnic differences among adult vaccination in the United States [21–23]. However, recent studies indicate that racial/ethnic disparities among childhood vaccination have been significantly reduced or not observed for some vaccinations [24,25]. Among adolescents 13–17 years, differences in HepB vaccination coverage among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites were no longer significant after controlling for demographic characteristics and access to care variables in the multivariable model. Middle-school mandates may contribute to the reduced racial and ethnic disparities in HepB vaccination coverage [15,26]. Additionally, the Vaccine for Children (VFC) program, which provides vaccines at no cost to eligible children through the age of 18 years if families might not otherwise be able to afford vaccines, and enrollment in the State Children’s Health Insurance Plan may also help reduce racial and ethnic disparities in receipt of preventive services that include vaccination [15,27].

This study indicated disparities in HepB vaccination coverage based on health insurance status in the bi-variable analysis. However, health insurance status was not independently associated with HepB vaccination when controlling for demographic and access to care variables in the multivariable analysis. Our study and other previous studies estimated that approximately 6–7% of adolescents were uninsured [15,28] and these children were at greater risk of not being vaccinated as recommended [15,28]. Our finding of similar HepB vaccination coverage by insurance status may be due to the contribution of the VFC program and CDC’s Vaccines for Children and Section 317 Cooperative Agreement [29–32]. The Vaccines for Children and CDC’s Section 317 Cooperative Agreement provides federal funds to state and local health departments to support immunization infrastructure to ensure access to vaccination services. These programs may help improve vaccination coverage among uninsured adolescent populations. Federal, state, and local partners should continue to build support for adolescent vaccination and address pockets of need for uninsured adolescents. Additionally, military health insurance is associated with lower vaccination rates through this association did not remain in the multivariable analysis. The population may be more transient which may have implications for more preventive services including vaccination. Further study is needed to look into reasons for gaps in HepB vaccination between adolescents with military health insurance and other health types of health insurances.

HepB vaccination coverage among adolescents 13–17 years varied by state and region of residence. Factors that might have contributed to the variability in vaccination coverage include differences in the way state vaccination programs are implemented, in medical-care delivery infrastructure; in the effectiveness of interventions being implemented by states other stakeholders; in population attitudes toward vaccinations; in immunization resources; in reimbursements for vaccines and vaccine administration; and in state and local policies (e.g., laws requiring vaccines for school entry) [33–40].

We found that about 7% of adolescents 13–17 years in 2012 had not received the complete HepB vaccination series, placing them at risk for infection and cancer and highlighting the need for continued provision of catch up vaccinations. However, our study showed that adolescent HepB vaccination catch-up coverage during ages 11–12 years decreased four-fold from 48% for those born in 1989 to only 12% for those born in 1999. This may reflect a decreasing emphasis by clinicians on assessing HepB vaccination status over time as more adolescents were vaccinated during infancy or early childhood, and many adolescents had opportunities to receive HepB vaccination when receiving other vaccinations. The ACIP and other partner organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Medical Association, and Society for Adolescent Medicine, recommend a well-child visit for children ages 11–12 years to receive recommended vaccinations and indicated preventive services such as vaccinations required to attend middle school [15,26,41]. Our study showed that the majority of adolescents not fully vaccinated against HepB had at least one visit where other vaccinations were provided. Approximately 80% of adolescents who did not receive any doses of HepB vaccine could have received at least one dose if the opportunity to provide a vaccination was not missed. Approximately 63% of adolescents with only one dose of HepB vaccine could have received the second dose if the opportunity to provide a vaccination was not missed. Using Immunization Information Systems (IIS) and client reminder and recall systems with standing orders, provider reminders for vaccinations or provider assessment/feedback have been shown to be effective strategies to assist vaccinations providers to routinely provide HepB vaccination to their patients, ensuring fewer missed opportunities and higher vaccination coverage [42].

The findings in this study are subject to limitations. First, household response rate is 55.1%, and some bias may remain after weighting adjustments designed to minimize non-response bias [43]. However, the basic demographic characteristics by age, gender, and race/ethnicity from the 2012 National Immunization Survey-Teen were similar to those observed in the child core data of the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (CDC unpublished data). Second, provider-confirmed vaccination histories might not include all vaccinations received, such as a HepB vaccination received in a birth hospital or HepB vaccinations provided by someone other than the vaccination provider listed by the parent or guardian. This could result in underestimated vaccination coverage as measured by the NIS-Teen. Third, vaccination estimates from landline only (2007–2010) and dual sampling frames (2011–2012) might not be comparable. However, prior methodological assessment suggests that the addition of cellular telephone numbers beginning in 2011 should have had limited effects on annual national coverage estimates [14]. Fourth, NIS-Teen excluded persons without telephones and subsequently may result in possible selection bias. Finally, there may be some associations between insurance status, socioeconomic status and facility type where vaccines are received and further study or investigation is needed to assess the association and its impact on vaccination.

HepB vaccination coverage among adolescents is now at a high level; however, additional improvement is feasible and opportunities for adolescent catch-up vaccination efforts should not be missed. Increasing use of HepB vaccine has resulted in decreased cases of acute HBV infections among persons aged ≤19 years (incidences among persons aged ≤19 years were 0.61 in 2000, and 0.03 in 2012, respectively, per 100,000 population) [17]. NIS results indicate HepB vaccination is stable around 90%. But by 2012, about 7% of adolescents 13–17 years had not received the complete HepB vaccination series and among adolescents who had not received the full HepB vaccination by 11 years of age, the proportion who received catch-up HepB vaccination during ages 11–12 years was low (9–15%) indicating catch-up as part of school entry may not reach all those unvaccinated as infants. Even though vaccination at younger ages is recommended and preferred to reduce serious complications from infection, catch-up vaccination is particularly important since catch up vaccination can provide protections and may be the last opportunity to provide protection before risk behaviors are likely to be initiated [8,10]. Eligible adolescents can receive recommended vaccines at no cost through Vaccines for Children (VFC) program. Providers, parents, and adolescents should use every health-care visit, whether for health problems, well-checks, or physicals for sports, school, or camp, as an opportunity to review adolescents’ vaccination histories and ensure that every adolescent is fully vaccinated with HepB vaccine and other recommended vaccines [41,44].

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest to be stated.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR. 2006;55(RR-16):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part 1: Immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR16):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W, Simard EP, Finelli L, McQuillan G, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States in the era of vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2010 Jul;202(2):192–201. doi: 10.1086/653622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunization in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J. 2006;332:328–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38719.435833.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillie SF, Murphy TV. Seroprotection after recombinant hepatitis B vaccination among newborn infants: a review. Vaccine. 2013;31:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schillie S, Murphy TV, Sawyer M, Ly K, Hughes E, Jiles R, et al. CDC guidance for evaluating health-care personnel for hepatitis B virus protection and for administering post-exposure management. MMWR. 2013;62(RR-10):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Inactivated hepatitis B vaccine. MMWR. 1982;31:317–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination. MMWR. 1991;40(RR-13) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 09.01.14];The ABCs of hepatitis fact sheet. 2010 Publication No. 21-1076. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Resources/Professionals/PDFs/ABCTable.pdf.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: recommendations to prevent hepatitis B virus transmission – United States. MMWR. 1995;44:574–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence MH, Goldstein MA. Hepatitis B immunization in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;17:234–43. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00165-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: recommendations to prevent hepatitis B virus transmission – United States. MMWR. 1999;48:33–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years – United States, 2006. MMWR. 2007;56:885–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years – United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(34):685–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain N, Hennessey K. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among U.S. adolescents, National Immunization Survey-Teen, 2006. J Adolesc Health. 2009 Jun;44(6):561–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis – United States, 2007. MMWR. 2009;57(SS-03):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 09.01.14];Viral hepatitis statistics & surveillance. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/2011Surveillance/Commentary.htm#hepB.

- 18.Jain N, Singleton JA, Montgomery M, Skalland B. Determining accurate vaccination coverage rates for adolescents: an overview of the methodology used in the National Immunization Survey-Teen 2006. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):642–51. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 09.06.14];National Immunization Survey-Teen. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/HealthStatistics/NCHS/DatasetDocumentation/NIS/NISTEENPUF12DUG.pdf.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Notice to readers. FDA approval for infants of a Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate and hepatitis B (recombinant) combined vaccine. MMWR. 1997;46:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu PJ, Singleton JA, Euler GL, Williams WW, Bridges CB. Seasonal influenza vaccination of adult populations, U.S., 2005–2011. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 Nov;178(9):1478–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu PJ, Santibanez TA, Williams WW, Zhang J, Ding H, Bryan L, et al. Surveillance of influenza vaccination coverage – United States, 2007–08 through 2011–12 influenza seasons. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013 Oct;62(Suppl 4):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Non-influenza vaccination coverage among adults – United States, 2011. MMWR. 2013;62(04):66–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wooten KG, Luman ET, Barker LE. Socioeconomic factors and persistent racial disparities in childhood vaccination. Am J Health Behav. 2007 Jul-Aug;31(4):434–45. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months – United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(36):733–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enger KS, Stokley S. Meningococcal conjugate vaccine uptake, measured by Michigan’s immunization registry. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanofi Pasteur. [accessed 16.01.14];Statement regarding the availability of Menactra vaccine. 2005 Available at: http://www.acha.org/sanofipasteur_7-19-05.pdf.

- 28.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Byrd KK, Murphy TV. Hepatitis. A vaccination coverage among adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb;129(2):213–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 13.01.14];Vaccines for children program. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/default.htm.

- 30.Ching PL. Evaluating accountability in the Vaccines for Children program: protecting a federal investment. Public Health Rep. 2007 Nov-Dec;122(6):718–24. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008–2009. Pediatrics. 2011 Nov;128(5):830–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 11.06.14];Immunization Program Operations Manual (IPOM) (Vaccines for Children and Section 317 Cooperative Agreement) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/guides-pubs/ipom/basics.html.

- 33.National, state, and local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years – United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(32):1018–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee GM, Santoli JM, Hannan C, Messonnier ML, Sabin JE, Rusinak D, et al. Gaps in vaccine financing for underinsured children in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:638–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Clark SJ. Primary care physician perspectives on reimbursement for childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1319–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodewald LE. Timing of the implementation of new vaccines in the VFC program. Presented at: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US)/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Tribal Consultation Advisory Committee meeting; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pruitt SL, Schootman M. Geographic disparity, area poverty, and human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:525–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Gregory S, Clark SJ. Variation in provider vaccine purchase prices and payer reimbursement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1325–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindley MC, Smith PJ, Rodewald LE. Vaccination coverage among U.S. adolescents aged 13–17 years eligible for the Vaccines for Children program, 2009. Public Health Rep. 2011 Jul-Aug;126(Suppl 2):124–34. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [accessed 13.01.14];Hepatitis B prevention mandates for children in day care and schools. Available at: http://www.immunize.org/pdfs/hepb.pdf.

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0–18 years – United States, 2013. MMWR. 2013;62(Suppl 1):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) The community guide. Atlanta, GA: 2013. [accessed 13.01.14]. The guide to community preventive services. Available at http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dolson D. [accessed 16.07.14];Errors of non-observation: dwelling nonresponse and coverage error in traditional censuses. Available at: http://www.amstat.org/sections/srms/proceedings/

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2011;60(RR-2) [Google Scholar]