Abstract

The objective in routine analyses is generally to determine a small number of analytes. With samples containing ~103 or more components there will be insufficient peak capacity to resolve analytes from nonanalytes. This issue was addressed herein through a new type of separation mechanism in which small groups of targeted analytes are bound with high affinity to a soluble analyte-sequestering transport phase (ASTP) composed of a ~25 nm Stokes radius hydrophilic polymer core (HPC). When introduced into a 30 nm pore diameter size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column, ASTP/analyte complexes elute within minutes, together, unretained, and relatively pure in the first chromatographic peak. Nonanalytes, in contrast, enter pore matrices of the packing material, are retarded in elution velocity, and are eluted later, separated from analytes. Fabrication of ASTPs was achieved by covalently coupling an antibody or some other affinity selector to a high molecular weight HPC. Beyond sequestering analytes, the function of ASTPs is to act as a molecular weight shifting agent, conveying an effective molecular weight to analytes that is much larger than that of nonanalytes and causing them to elute in the SEC void volume. This mode of separation is referred to as mobile affinity sorbent chromatography (MASC). Subsequent to their purification, ASTP/analyte complexes were detected by fluorescence spectrometry.

Graphical abstract

Liquid chromatography (LC) is widely used in life science research and diagnostics to routinely determine small numbers of analytes in large numbers of samples. An inherent problem with the two-phase partitioning mechanism used in LC is that analytes and nonanalytes elute codispersed among 50 to several hundred peaks spread across 10–50 column volumes of mobile phase. Substantial time is expended waiting for analytes to elute. Additionally, there is the problem that a large percentage of the components in samples are initially bound; as with reversed phase chromatography. With samples of 103–104 components, elution fractions can contain 10–100 substances. This complicates identification and quantification.

Immunoaffinity chromatography readily addresses many of these problems by selectively binding analytes based on their three-dimensional structure.1 Nonanalytes elute without retention. Although this diminishes the need for large numbers of theoretical plates, there is still the issue of needing 10–20 columns volumes of mobile phase to elute nonanalytes and nonspecifically bound substances, to desorb analytes, and to recycle the immobilized antibody after analyte elution. A second limitation is that a large excess of immobilized antibody must be used to achieve the requisite rapid adsorption of analytes.2 Finally, there is the issue of carryover. Quantification of an analyte in low abundance is frequently compromised when preceded by a sample of high analyte concentration. Multiple blank gradient elution cycles are often needed to elute residual high abundance analytes.3

The work presented herein is directed toward conceiving and validating a new chromatographic mode referred to as mobile affinity sorbent chromatography (MASC) that circumvents these issues by (i) selecting analytes for purification based on specific 3D structural features, (ii) isocratic elution, (iii) performing separations with one column volume of mobile phase, (iv) capturing and transporting analytes through columns with a transport phase that elutes in the column void volume, and (v) using new analyte-targeting sorbent in each analysis.

The enabling feature of MASC is that a third analyte-sequestering transport phase (ASTP) of 2 MDa is added to a conventional size-exclusion chromatographic system. The function of this new transport phase (Pt) is to sequester analytes of interest immune-specifically with high selectivity and affinity, after which they are coeluted from an SEC column in a single nonretained peak, while the accompanying conventional size-exclusion stationary phase retards migration of nonanalytes. While mobile phase would still play the role of mediating adsorption and transport, ASTP sorbent will be discarded after a single use. This three-phase chromatographic system would achieve identification and quantification of a small number of recurring analytes in large numbers of complex samples by having analytes of interest elute together, irrespective of their structures, unretained in a single chromatographic peak where they could be differentially identified and quantified. Substances eluting later would be of no interest and could be discarded.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant PA/G (77678, lot no. RL246438), human IgG, and goat antimouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 (Ab2*) (A28181, lot no. RA228327) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Hydrophilic polymer core (HPC), HPC–CH═O, HPC–NH2, HPC–fluorescein isothiocyanate (HPC–FITC), and HPC–PA/G (HPC–PA/G) are products of Novilytic, LLC (West Lafayette, IN). Sodium phosphate dibasic, sodium phosphate monobasic, sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), protein standards, and anti-fluorescein (FITC) antibody (clone 5D6.2, MAB045, lot no. 2676650) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All reagents were used without further purification, unless specified. A 4.6 × 300 mm Sepax SRT-C SEC-300 column packed with 30 nm pore diameter, 5 um particle size material was obtained from Sepax (Newark, DE).

Methods

Size-Exclusion Chromatography

SEC was carried out with a Shimadzu Prominence UPLC System using a CBM-20A system controller, four Shimadzu LC-20AD pumps, two DGU-20A5 degassers, an SIL-10AXL auto sampler, a CTO-20AC column oven, an SPD-20A UV–vis detector, and an RF-20Axs fluorescence detector. Samples of 5–200 µL were injected and separated with a Sepax SRT-C SEC-300 size-exclusion column (4.6 × 300 mm, 5 µm particles, 300 Å pore diameters, Sepax Technologies, Newark, DE). The mixture was eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min with 150 mM, pH 7.0 sodium phosphate aqueous buffer. Buffers were filtered with Millipore Express Plus 0.22 µm filter (purchased from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) before use. Both detectors were set to the dual-wavelength mode. The UV–vis detector was set to measure absorbance at 214 and 280 nm, while the fluorescence detector was set to measure excitation/emission wavelength pairs at 280 nm/348 nm and 494 nm/519 nm for FITC-labeled proteins. Alternatively, 651 and 667 nm were used for the measurement of Alexa Fluor 647 labeled proteins.

FITC Labeling of Proteins

Twenty µL of freshly prepared FITC solution (5 mg/mL in 0.1 M pH 9.0 sodium carbonate buffer) was added to 100 µL of a protein sample (5 mg/mL) and mixed with 80 µL of sodium carbonate buffer (0.1 M pH 9.0) followed by a 12 h incubation in darkness. The reaction mixture was then loaded onto an Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (EMD Millipore 0.5 mL Ultracel-30K, Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 14 000 × g for 10 min, after which the filtrate was discarded. Three hundred eighty µL of 150 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was added to the filter device, followed by 10 s of vortex mixing. This centrifugation process was repeated five times to ensure removal of unreacted FITC, after which the FITC-labeled protein was collected from the filter device.

Complexation of PA/G with IgG

Six µL of 100 µg/mL PA/G was mixed with 2 µL of 1 mg/mL human IgG and 12 µL of 0.1 M, pH 7.0 sodium phosphate buffer, giving final PA/G and IgG concentrations of 30 and 100 µg/mL, respectively. The mixture was vortex-mixed for 10 s and incubated in darkness for 30 min. Bound-to-free ratios were determined by SEC using a 5 µL sample of the described mixture.

Complexation of ASTPs with FITC-IgG

Five µL of ~3.5 mg/mL HPC–PA/G were mixed with various amounts of FITC-IgG solution (~160 µg/mL, from 1 to 45 µL), and 150 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was added to a total volume of 50 µL. The mixture was vortexed for 10 s and incubated in darkness for at least 30 min before 5 µL of the mixture was analyzed by SEC.

Complexation of ASTPs with IgG in Human Plasma

One hundred µL of ~3.5 mg/mL HPC–PA/G was mixed with 67.5 µL of filtered and diluted human plasma (~2 mg/mL in protein concentration that had been diluted with pH 7.0 sodium phosphate buffer), and 32.5 µL of sodium phosphate buffer was added to a total volume of 200 µL. The mixture was vortexed for 10 s and incubated in darkness for at least 30 min. One hundred ninety µL of this mixture was injected into the LC system and eluted isocratically at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Eluent fractions of 0.5 min duration were collected between 2.0 and 4.0 min. These fractions were then concentrated 5–10-fold via Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filters and preserved in darkness at 4 °C before use.

Purification of Ab2*

High molecular weight impurities were removed from fluorescent-labeled secondary antibody (Ab2*) purchased from ThermoFisher by SEC. Two hundred µL of 200 µg/mL Ab2* aqueous solution was injected to the LC system and eluted isocratically using 150 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The fraction between 2.8 and 3.5 min was collected and preserved in darkness at 4 °C.

Sandwich Assay

Five µL of 0.5 mg/mL HPC–FITC was mixed with 25 µL of 200 µg/mL filtered human plasma, to which 0.5–10 µL of 10 µg/mL monoclonal anti-FITC antibody produced in mouse (Ab1) was added, and pH 7.0 sodium phosphate was added to a total volume of 40 µL. The mixture was vortexed for 10 s and incubated in dark at room temperature for 30 min. Then 10 µL of purified 40 µg/mL Ab2* (Alexa Fluor 647 labeled antimouse antibody) was added and vortexed for 10 s, after which it was incubated in darkness at room temperature for another 30 min before 10 µL of the mixture was analyzed by SEC.

SDS-PAGE

HPC–PA/G was incubated with human plasma for 30 min. The immune complex was fractionated with a Sepax SRT-C SEC-300 size-exclusion column (4.6 × 300 mm packed with 5 µm particles of 300 Å pore diameter, Sepax Technologies, Newark, DE). The mixture was isocratically eluted as described earlier, and fractions were collected every 30 s. Each eluted fraction was concentrated 5–10 times with an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (10K MWCO, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Concentrated samples were added to an equal volume of 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) and heated for 5 min at 95 °C in a water bath. The samples were analyzed in 10% Mini-Protean TGX precast gel according to the supplier’s protocol. Dual-color standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) of 10 µL were used as a molecular weight marker. Gels were stained with Brilliant blue G solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and destained by using 10% MeOH and 5% acetic acid in water.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Theory

The new transport phase being proposed herein and the manner in which it is used are central components of the system described in the introduction of this Article. It was reasoned that, by using an affinity selector immobilized on the surface of a globular hydrophilic polymer exceeding 2 000 kDa, or in fact any soluble hydrophilic polymer with a Stokes radius (Rs) exceeding 25 nm, it would be possible to fabricate a transport phase (Pt) that could structure specifically bind analyte(s) with high affinity and cause them to elute from a size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) matrix without retention. The affinity selector with bound analyte(s) will elute ahead of nonanalytes that are partially retained as a consequence of entering the pores in a molecular sizing SEC column.

The requisite affinity selectors used in this study were antibodies, antibody-binding proteins, and haptens. All are well-known in affinity chromatography and immunological assays.4

Binding an analyte to an immobilized selector such as an antibody involves large numbers of collisions with the immunosorbent surface before the requisite intermolecular alignment for docking is achieved.5 It is for this reason that the on-rate of adsorption (ka) in affinity chromatography6 is slower than that with reversed-phase or ion-exchange chromatography, where there is far less dependence on spatial complementarity for binding. Having bound to an affinity selector, it is important in MASC that the rate of dissociation (kd) be very low to ensure continued association with the sorbent during elution.

At equilibrium, the association constant Ka of an analyte with the affinity sorbent can be represented by the expression

| (1) |

where ka and kd are the respective association and dissociation rate constants, [Sa] is analyte/sorbent complex concentration, and [S] and [AF] are the respective concentrations of free sorbent and free analyte.7 With a good affinity selector such as an antibody, Ka would typically be 106 M−1 or more.

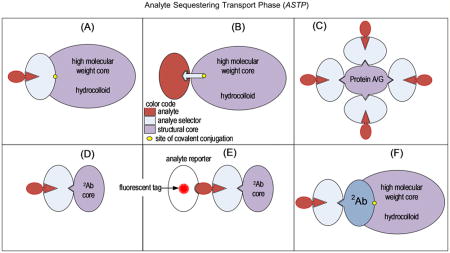

A premise guiding the work described herein was that, by covalently linking antibodies, or in fact any structure-specific affinity selector (S), to a soluble hydrophilic macromolecular core of 2 000 kDa or more, ASTP illustrated in Figure 1A–E could be created. Desirable properties of the ASTP would be that it (i) exceeds the molecular weight of most proteins and metabolites 2-fold or more, (ii) elutes in the void volume (V0) of an SEC column before other biological species, (iii) allows dissociation of nonspecifically bound species from Sa during migration through the column, and (iv) enables orders of magnitude purification of an analyte using a single column volume of mobile phase.

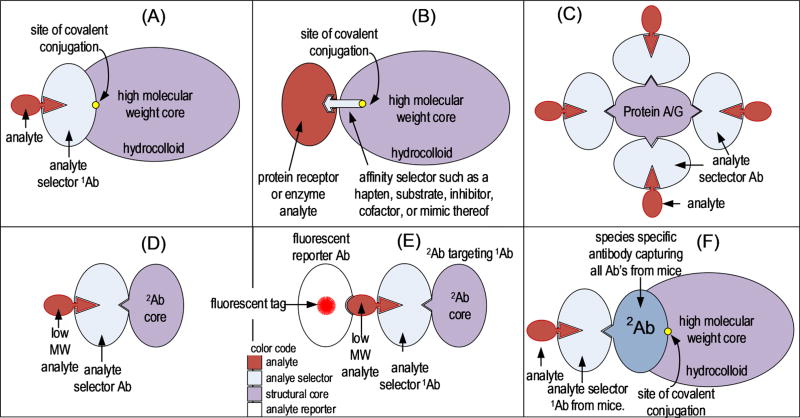

Figure 1.

Illustration of the hypothetical components in an analyte-sequestering transport phase (ASTP) with bound analyte. (A) Covalently immobilized analyte selector that can be a primary antibody, a binding protein, or an aptamer, while the analyte could be a protein, peptide, metabolite, or drug. (B) Affinity selector that could be a low molecular weight species such as a hapten, substrate, inhibitor, or cofactor. Analytes in this case would generally be a protein having an affinity for one of these low molecular weight selectors. The high molecular weight core illustrated in panels A and B would be functionalized at one site, which could be with a carbonyl, primary amine, or carboxyl functional group. (C) Core structure that is PA/G; (D, E) illustration of a monoclonal antibody core. The ASTP in panel C is a special case in which multiple affinity selector antibodies are bound by a single molecule of PA/G. It is important to note that the stoichiometry of components in an ASTP could differ from these illustrations based on reaction conditions used in their synthesis.

Several exceptions to the neutral, hydrophilic polymer core (HPC) were also tested in ASTP fabrication (Figure 1C–E). Antibodies themselves were used as the mass-shifting core of the ASTP in these cases. They too will achieve the objective of binding to an ASTP in the separation of bound from free analytes by SEC to obtain high levels of purification, as seen in Figure 2 (inset). There is no need in this approach to separate analytes from high molecular weight proteins when the object is simply to separate low molecular weight analytes from other low molecular weight species.8

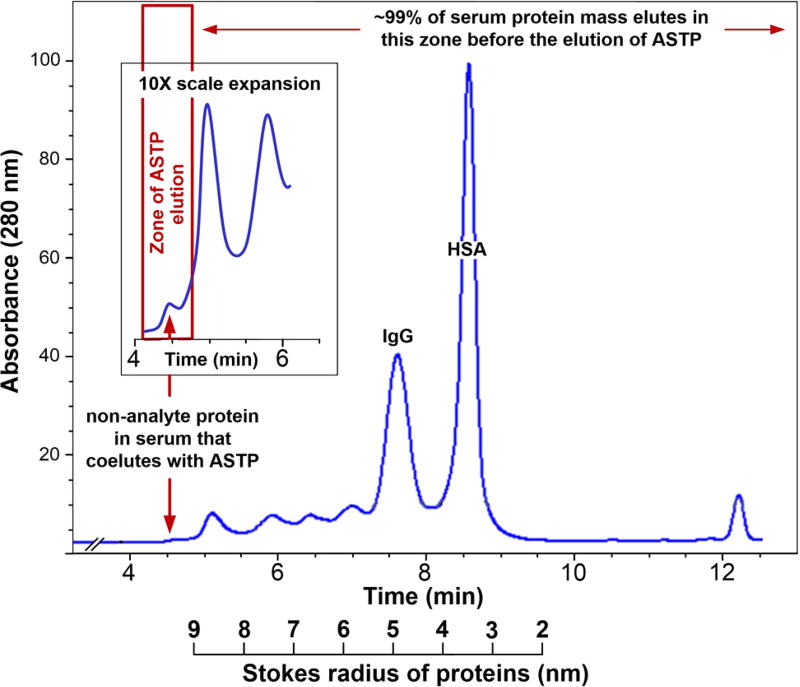

Figure 2.

Size-exclusion chromatogram of human serum using a 4.6 × 300 mm Sepax column packed with 30 nm pore diameter, 3 um particle size material. The column was eluted with 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 1 mL/min. Detection was achieved by absorbance at 280 nm.

The elution volume (Ve) of an SEC column is expressed by eq 2,

| (2) |

where V0 is the column void volume and Ksec is a distribution coefficient unique to SEC that ranges from zero for excluded species to 1 for low molecular weight substances that penetrate the entire pore volume of the column.9 The term θ is the volumetric phase ratio of the SEC column where θ = Vi/V0 and Vi is the column pore volume. Theta is a function of the chromatographic packing material unique to the particle manufacturer, generally ranging from 1.1 to 1.3.

On the basis of the equilibrium in eq 1, the fraction (F) of analyte that can enter the pore matrix of an SEC column subsequent to association with an excluded ASTP is

| (3) |

where [At] is the total amount of analyte in the system. Equation 3 shows that, when the association constant [Ka] is high, [AF] will approach 0, which is the ideal case. Combining eqs 2 and 3 shows the impact of F on analyte elution volume from a MASC column:

| (4) |

Merging eqs 3 and 4 produces a more general expression,

| (5) |

which predicts elution volume (Ve) of an analyte based on its concentration, size-exclusion characteristics, and binding affinity to the transport phase.

Ideally, elution volume (Ve) would be expressed in terms of the dimensionless capacity factor10 (k′) where

| (6) |

This allows reduction of eq 5 to the term

| (7) |

Considering that Ksec, θ, and total analyte concentration of analyte [At] are constants, eq 7 can be further reduced to

| (8) |

where the constant C = θKsec/[At]. When Ka is 106 M−1 or larger, k′ will approach 0, which means Ve = V0 and the ASTP/analyte complex will be excluded in SEC. In contrast, when Ka is low, elution volume will depend increasingly on the fraction (F) of analyte penetrating the SEC column pore matrix. None of the requisite criteria for MASC will be met. Also, when the analyte is so large that Ksec = 0, it is impossible to achieve the requisite resolution of free analyte from analyte/sorbent complex. The bound-to-free ratio of analytes cannot be determined in this case.

An important issue in MASC is being able to predict the molecular weight ratio (Rm) between the ASTP/analyte complex Sa and an immediately adjacent nonanalyte following behind. It will be assumed in this case that the analyte complex and trailing nonanalyte have a resolution (R) of at least 1 where R = (Ve2 – Ve1)/4σ. The terms Ve1 and Ve2 are the elution volumes of the first and second eluting peaks, respectively, and σ is the average standard deviation of their elution volumes.11 Predicting the molecular weight of the nearest eluting nonanalyte provides an understanding of the resolution of ASTP sequestered analyte from other substances in a sample.

It has been shown that Rm in SEC is predicted by eq 9,

| (9) |

where m is the slope of the size-exclusion calibration curve, Ve1 is the elution volume of the first peak of the pair, Vi is the pore volume, H is the theoretical plate height, L is the column length, and N is the total number of theoretical plates in the column.12 The slope of the calibration curve for SEC media of narrow pore distribution is ~2. Thus, eq 9 predicts that, with a column having a 2 000 kDa exclusion limit, a Ve1/Vi ratio of 1.3, and 10 000 theoretical plates, the analyte-to-nonanalytes resolution will be one for a 600 kDa substance relative to the 2 000 kDa ASTP/analyte complex. This means that substances of <600 kDa in a sample will be resolved from analytes. The exception would be proteins of highly asymmetric shape.

Asymmetrically shaped proteins are in general treated as outliers in SEC.13 The common method of calibrating SEC columns is to plot elution volume (Ve), or elution time versus the log of protein molecular weight12 (Mw), assuming a linear relationship between Ve or elution time and log Mw. That practice was followed in the derivation of eqs 4–9. While valid with most proteins, it is not valid for the small number of structurally asymmetric proteins that elute earlier than their Mw would predict.14 This is because protein elution volume in SEC is more accurately predicted by Stokes radius (Rs) than log Mw15 (Figure 2). Whereas thyroglobulin has a molecular weight of ~606 kDa and a Stokes radius (Rs) of 8.5, the rod-shaped protein fibrinogen has a molecular weight of ~387 kDa and an Rs of 10.7. Thus, fibrinogen elutes before thyroglobulin. This means that proteins smaller than 600 kDa could be excluded from a 30 nm pore diameter column. Why then are log Mw versus elution volume plots so widely used? The Stokes radius of proteins is generally determined by analytical ultracentrifugation and is not available for most proteins.16

Although the SEC behavior of asymmetric proteins is a scientifically valid concern, in reality it poses little problem with MASC. The amount of excluded protein in an SEC chromatogram of human serum (Figure 2) shows that <1% of the total protein in the serum will elute in the void volume with ASTP/analyte complexes.

This discussion implies the ASTP must be added to the mobile phase continuously, but when the association constant in eq 1 is 106 M−1 or larger, the analyte will essentially be irreversibly bound to the ASTP during the entire time it is being transported through the SEC column. There is no need to continuously add ASTP in this case. Only a small part of the transport phase would actually be used in analyte binding.

This allows an alternative to continuous ASTP addition. Transport phase can be pre-equilibrated with a sample before addition to the SEC column, which allows analyte sequestration on the ASTP to reach equilibrium before injection into the SEC column. Subsequent to injection the analyte equilibrated transport phase zone will behave as a very short affinity column. Weakly bound substances that desorb and subsequently enter the pore matrix of the column will disengage from the fast-moving ASTP zone, which precludes the possibility of rebinding. This has the advantage of stripping weakly bound nonanalytes from particles in a short distance. In effect, this provides a separation based on off-rate selection, similar to eluting a conventional short affinity chromatography column with large volumes of mobile phase. Nonanalytes and substances such as proteoforms with a high off-rate will migrate through the MASC column at a slower velocity than the analyte bearing transport phases. This elution mode will be referred to as zonal MASC.

ASTP Fabrication

As seen in the Figure 1 illustration, critical components of an ASTP are the analyte affinity selector and the core structure to which selectors are attached. Preferably the core will be very large to make the molecular weight of the ASTP/analyte complex much higher than that of nonanalytes.

Several criteria were used in searching for core structures to be used as transport phases. One is their ability to preclude ASTP entry into SEC matrix pores. A second is that the ASTP molecular weight distribution is sufficiently narrow to preclude entry of lower molecular weight forms into pore matrices with concomitant peak tailing. Still another is that affinity selector immobilization could be achieved easily. Finally, the core should show minimal interaction with the size-exclusion matrix. Hydrophilic macromolecular substances ranging from polypeptides and protein aggregates to soluble hydrophilic polymers (Table 1) most nearly meet these criteria.

Table 1.

Core Structure Candidates Used in ASTP Fabrication

| particle core | approx. Mw in kDa (g·mol−1) | approx. # Ab per particle | ASTP Mw in kDaa (g·mol−1) | selector attachment mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| protein A/G | 50–60 | 2–5 | 380–1250 | adsorption | affinity |

| Ficoll | average 400 | 1–6 | 560–1360 | covalent | Schiff base |

| IgG (mAb) | ~160 | 1 | 320–480 | adsorption | affinity |

| HPCb | ~2000 | 1–10 | 2200–3600 | adsorption | affinity |

This refers to the approximate gram Mw of the selector/core complex in kilodaltons.

HPC is an abbreviation for hydrophilic polymer core.

Native protein A and protein G are well-known to bind strongly to the Fc structural domain of immunoglobulin G.17 This has led to them being used in immobilized form for antibody (Ab) purification.18 It is important to note, however, that they differ in binding affinity for antibodies from different species.19 They also contain binding sites for serum albumin and cell wall components.20 This has led suppliers to produce genetically engineered versions of these immunoglobulin-sequestering proteins (ISPs) in which the Fc-binding domains are retained but binding sites for other proteins have been deleted.21 These hybrid ISPs contain Fc-binding domains from protein A, protein G, or both, which are designated herein as protein A′, protein G′, and protein A/G (PA/G), respectively. The largest advantage of PA/G is that it binds most mammalian IgG subclasses22 with an association constant in the range of at least 106 M−1 according to suppliers.

When PA/G at 30 µg/mL was mixed with human IgG (100 µg/mL) and separated by SEC (Figure 3A), at least 5 peaks were observed ranging from 500 kDa to >1 MDa. Clearly, PA/G binds multiple molecules of IgG, but with variable stoichiometry. This has not been previously reported. Failure of PA/G to form a single, fully saturated PA/G/(Ab)n complex, even at an IgG-to-PA/G molar ratio of 10:1 is a serious limitation that precludes this approach to ASTP fabrication. The model for formulating an ASTP provided in Figure 1C is concluded not to be a viable candidate. Analyte elution in multiple peaks decreases detection sensitivity, complicates identification, and increases the RSD in quantification. Lower molecular weight PA/G/Ab/analyte complexes would coelute with nonanalyte proteins of 300–400 kDa.

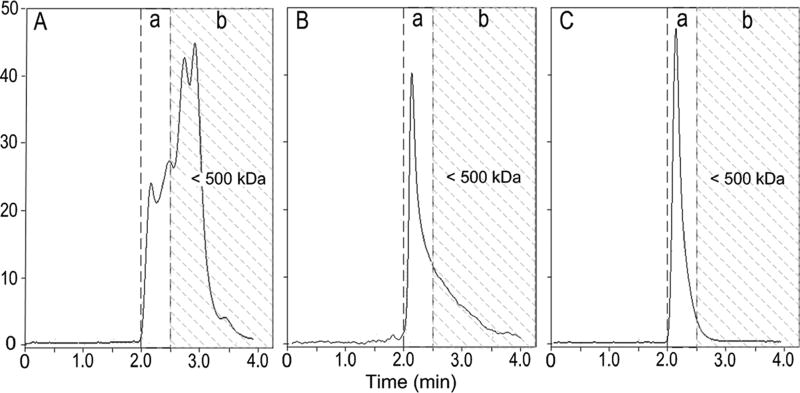

Figure 3.

Size-exclusion chromatograms of transport phases with a bound affinity selector. (A) Chromatogram of PA/G loaded with IgG at roughly a 3:1 molar ratio of IgG to PA/G. (B) Chromatogram of oxidized Ficoll 400 to which 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP) has been covalently linked. (C) Chromatogram of a hydrophilic polymer core (HPC) of ~2 000 kDa to which PA/G has been conjugated. Substances eluting in the shaded area are in nonanalyte regions of the chromatogram. Separations were achieved with a 4.6 × 300 mm Sepax SEC column packed with 30 nm pore diameter, 3 um particle size media. Detection was by absorbance at 215 nm.

Ficoll has been widely used in biological research and medical applications requiring high-mass, hydrophilic polymers.23 It is produced by extensive cross-linking of sucrose with epichlorohydrin,24 resulting in a spherical polymer that swells less in buffers than natural polysaccharides according to suppliers. Ficoll of 400 kDa (±100 kDa) was periodate oxidized to generate carbonyl groups.12 Primary amines of proteins were couple to these carbonyl groups via Schiff base formation and NaCNBH3 reduction, precluding reversibility. Through 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine derivatization, the Ficoll-to-primary amine coupling stoichiometry was found to be ~1. SEC analysis of a Ficoll–PA/G complex showed a long tailing peak (Figure 3B), which is reaching down into the 200–300 kDa range.

These results indicate that a substantial amount of Ficoll–PA/G enters the pores of the 30 nm pore matrix. If used in the analysis of plasma samples, Ficoll–PA/G would trail into the thyroglobulin peak. On the basis of this fact, Ficoll was judged to be unacceptable and excluded as a prospective ASTP core material.

Antibody aggregation was also examined as a means to generate an ASTP. Aggregation was achieved by using a secondary antibody (2Ab) to target and bind to the Fc region of a primary antibody25 (1Ab). The function of the primary antibody in this case was to bind an antigen (Ag) target. The IgG dimers (2Ab/1Ab) formed (Figure 1D) were ~300–340 kDa based on the fact that IgG-type antibodies vary from ~145 to 170 kDa in Mw, depending on their subclass and species origin. Association of the 2Ab/1Ab complex with an antigen of 60–200 kDa produced an 2Ab/1Ab/Ag complex of 400–520 kDa (Figure 1C). The Theory section suggests that this IgG dimer approach will only resolve analytes from nonanalytes of <200–250 kDa. A substantial amount of plasma protein elutes from a 30 nm pore diameter SEC column in the molecular weight range above 200 kDa (Figure 2). This would be the case with many biological samples. It is concluded that IgG dimer could be used as a molecular weight shifter for haptens but not proteins greater than 25 kDa. Low molecular weight analytes would be selected by the IgG dimer and be resolved from other low molecular weight species. The problem with the 2Ab/1Ab dimer approach (Figure 1D and E) would be that it provides poor resolution of protein analytes from nonanalyte proteins of high molecular weight. For this reason, 2Ab/1Ab dimers should only be used in the analysis of low molecular weight substances. The advantage of this approach is the simplicity of ASTP fabrication.

The functionalized hydrophilic polymer core (HPC) used in this work had a mean Stokes radius of ~25 nm according to the supplier, causing HPC and the covalently coupled HPC–PA/G complex to be excluded from a 30 nm pore diameter SEC column (Figure 3C). On the basis of the performance of HPC in SEC experiments, it was concluded to have met all the requisite criteria for an ASTP core material as illustrated by models in parts A, B, and F of Figure 1. It was selected as the material of choice for ASTP fractionation.

Affinity Selector Coupling Chemistry

Affinity selectors bearing an immobilized antibody were fabricated using an HPC–CH═O core and Schiff base coupling with accompanying NaCNBH3 reduction.26 Alternatively, HPC–NH2 was used as the ASTP core and coupled to carboxyl groups on affinity selector proteins via a water-soluble carbodiimide.27 The Schiff based coupling approach was simpler.

Proof of Concept Experiments

As a MASC proof of concept, functionalized HPC to which PA/G had been conjugated (HPC–PA/G) was added to plasma bearing FITC-labeled IgG (designated as IgG* to indicate fluorescent labeling), forming a HPC–PA/G/IgG* complex. This sample was subjected to zonal mode MASC using the 4.6 × 300 mm, 30 nm pore diameter SEC column noted in the Methods section (Figure 4). Proteins seen in Figure 4 are molecular weight standards detected by absorbance at 280 nm. The excluded peak detected at 280 nm is a thyroglobulin dimer present in the thyroglobulin standard. This level of thyroglobulin dimer is not encountered in native plasma samples.

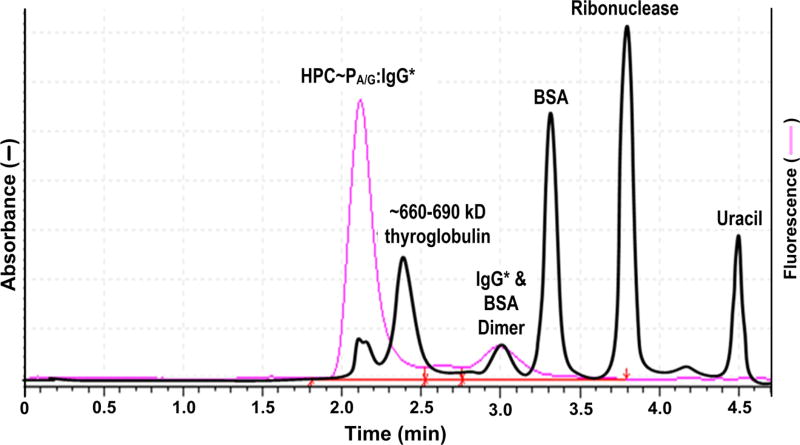

Figure 4.

Zonal-mode MASC separation of an HPC–PA/G/IgG complex showing retentions times of the transport phase–analyte complex relative to protein standards and unbound IgG*. Absorbance detection was at 280 nm, while fluorescence detection was achieved using excitation and emission wavelengths of 494 and 512 nm, respectively.

It is concluded that the HPC–PA/G/IgG* complex in the sample behaved as the theory of zonal MASC predicts. IgG* bound to the ASTP phase was transported through the column without interacting with the stationary phase, whereas unsequestered IgG* partitioned with the stationary phase as predicted (Figure 4). Moreover, it was further confirmed that (i) structure-specific selectivity could be built into an ASTP, (ii) the analyte IgG* could be isocratically separated from other protein species using a single column volume of mobile phase, and (iii) bound analyte behaves as if it had a molecular weight greater than 1000 kDa. Analyte elution behavior was molecular weight independent. Finally, it was validated that IgG* and nonanalytes not bound to the ASTP took a different path through the column. Unbound species of <600 kDa penetrated the pore matrix of the SEC packing material.

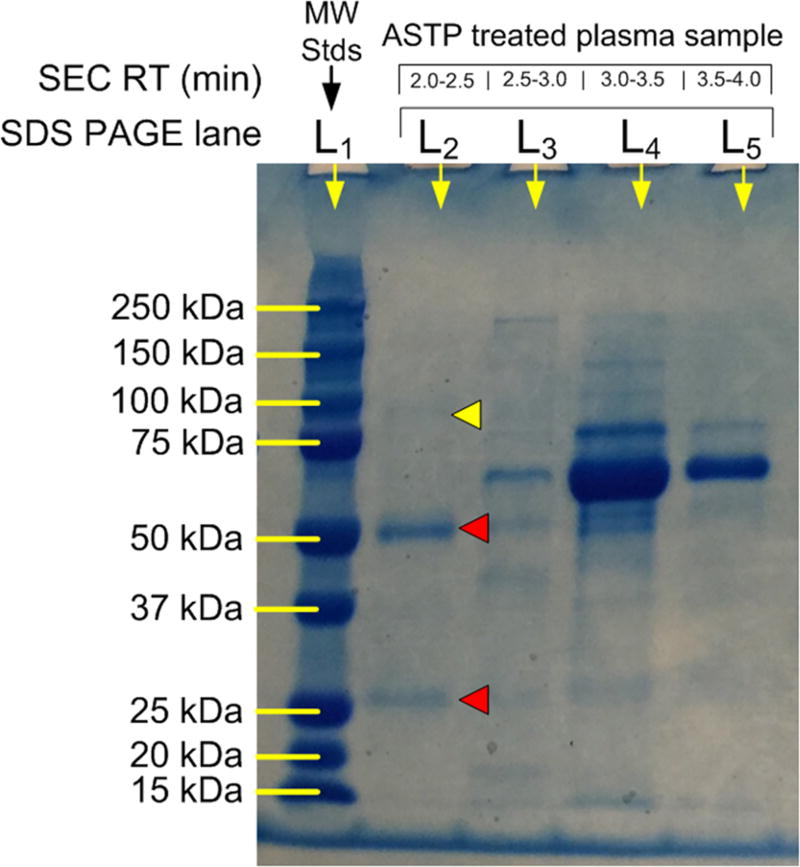

An issue in immunological assay methods is always the degree to which the immobilized affinity selector and immune complex nonspecifically bind other proteins.28 The zonal MASC approach illustrated in Figure 4 was used to examine nonspecific binding of proteins to an ASTP complex by adding HPC–PA/G in excess to a human plasma sample, forming the complex HPC–PA/G/IgG. One hundred µL of this sample was then subjected to zonal MASC using the same column and elution conditions as in Figure 4 (chromatogram not shown). Four fractions were collected and examined by SDS-PAGE (Figure 5), including the void volume fraction between 2.0 and 2.5 min elution time.

Figure 5.

SDS-PAGE electropherogram of SEC fractions from ASTP selected plasma sample.

SDS-PAGE showed that the molecular weight shifting strategy of sequestration by a high molecular weight ASTP separates IgG from other plasma proteins. Lane 1 shows the separation of molecular weight standards, while the lane 2 sample was derived from the excluded HPC–PA/G/IgG peak after reduction and exposure to SDS. Retained plasma proteins from the SEC column are seen in lanes 3, 4, and 5, with the elution times being seen above the electropherogram. The heavy (50 kDa) and light (25 kDa) chains from IgG are highlighted with red arrows in lane 2. A small impurity accented with a yellow arrow in lane 2 at 100 kDa is thought to have come from IgM.

The percent purity of an analyte (Anpurity) eluting from a MASC column is related to the amount of coeluting nonanalyte protein in the void volume peak. This is expressed by eq 10,

| (10) |

where [An] is analyte concentration in the void volume peak and [Pvv] = Cf [Tp]. [Pvv] is the concentration of nonanalyte protein in the void volume peak coeluting with the ASTP/analyte complex, [Tp] is the total concentration of protein in the sample, and Cf is relative concentration of void volume protein versus [Tp]. Relative concentration is estimated by SEC absorbance (Figure 2). Cf will in general vary little between samples and be in the range of 0.01 (Figure 2). Although 99% of nonanalyte protein is eliminated in a single pass through the SEC column, the degree to which low-abundance analytes are contaminated with nonanalytes is related to their concentration. A rough estimate of analyte purity can be predicted by assuming that (i) the total amount of protein in human plasma is 70 mg/mL, (ii) 1% of the total protein is in the void volume peak, and (iii) the average Mw of nonanalyte proteins in the void volume peak is ~700 kDa. With these assumptions it can be estimated on a molar ratio basis that an analyte at 10−6 M in a human serum sample would be 50% pure upon elution from an MASC column. Moreover, this level of purification would have been achieved in a few minutes, all of the impurities in the collected fraction would be large proteins, and, based on the frequency of molecules this size in serum, their number would be small.

Detection

It has been estimated by Grand View Research29 that in 2015 the global value of the monoclonal antibody market was 85.4 billion USD and will reach 138.6 billion USD by 2024. This has created a large need for rapid antibody-analysis methods in R&D, manufacturing, QC, and the diagnostic environment. The discussion below provides a general protocol by which antibodies can be rapidly analyzed.

Inherent in MASC is that selected analytes coelute in the void volume within a few min bound to an ASTP affinity selector of similar absorbance. This means the detection system must be able to discriminate between them. Fluorescence and mass spectrometry (MS) detection systems are both possible, but only fluorescence detection is reported here.

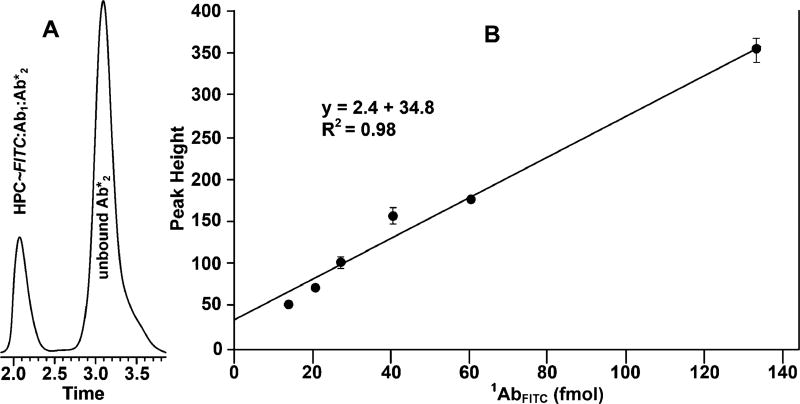

Fluorescence detection was achieved in a sandwich mode (Figure 1E) similar to that used in fluorescent immunological assays.30 The analyte being detected was a primary antibody targeting the antigen FITC, referred to below as 1AbFITC. Solutions of the same volume, but varying in the concentration of 1AbFITC, were added to 100 µL of human plasma bearing HPC–FITC, forming the immune complex HPC–FITC/1AbFITC. Detection was achieved by treating HPC–FITC/1AbFITC with fluorescent-labeled 2Ab* at a final concentration of 8 µg/mL. Subsequent to zonal MASC, HPC–FITC/1AbFITC/2Ab* was detected by fluorescence (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sandwich assay of a polyclonal primary antibody (1AbFITC) targeting FITC antigen covalently linked to the HPC. Detection was achieved by treating HPC–FITC/1AbFITC with fluorescent-labeled 2Ab*, forming the complex HPC–FITC/1AbFITC/2Ab*. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 494 and 512 nm, respectively. The error bars show standard deviation of the replicates.

Advantages of this MASC assay mode are that (i) the analyte immune complex sandwich containing separation and detection components is formed in a homogeneous solution environment, (ii) the sandwich is rapidly resolved and detected, and (iii) all the molecular species involved remain in solution throughout the assay. Homogeneous assays of this type accelerate the rate of immune-complex formation31 in addition to facilitating switching between analytes in sequential assays and multiplexing. At no time was phase separation of HPC–FITC/1AbFITC/2Ab* complexes observed.

Uniqueness of MASC

It is proposed herein that MASC is a new form of chromatography, but how does it compare mechanistically to size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), pairing-agent chromatography (PAC), restricted-access media (RAM) separations, electrochromatography (EC), and micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC). The easiest way to contrast these systems is via the number of phases involved in the separation process and the path of analyte versus nonanalyte migration through columns. The separation mechanism in SEC, PAC, RAM, EC, and MEKC is the result of simultaneous partitioning of analytes and nonanalytes between two phases based on some form of differential association and migration.32 Even pairing agent/analyte complexes interact with the stationary phase. MEKC differs slightly in that it has a migrating micellar sorbent phase,33 which could be thought of as being theoretically equivalent to the analyte-sequestering transport phase in MASC. However, MEKC is still a two-phase separation system.

MASC, in contrast, has three phases; a stationary phase equivalent to that used in conventional LC described earlier, a mobile sorbent transport phase similar to that used in MEKC, and a mobile phase. Features that make MASC unique are (i) the use of three phases to achieve separations, (ii) the fact that analytes bind to the mobile sorbent phase and are therefore precluded from binding to the stationary phase, and (iii) the fact that nonanalytes associate with the stationary phase but not mobile sorbent transport phase. These attributes make the separation mechanism in MASC totally different than all other forms of chromatography.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that mobile sorbent affinity chromatography of proteins and water-soluble haptens is enabled by the addition of an analyte-sequestering transport phase (Pt) to a conventional hydrophilic SEC column. Pt (i) must be soluble and easily dispersed in the SEC mobile phase when loaded with affinity selected analyte, (ii) must structure specifically sequester analyte(s) with an association constant exceeding 105 M−1, (iii) must also have a core structure composed of a soluble hydrophilic polymer exceeding 2 000 kDa that is excluded from the pores of the SEC column, and, finally, (iv) must not interact with the surface of the SEC matrix alone or when loaded with an analyte.

When these conditions are met, Pt-sequestered analytes will elute in the SEC column void volume irrespective of their molecular weight and properties. Analytes thus sequestered can be substantially purified with a 30 nm pore diameter SEC column. Under these conditions, analytes are separated from nonanalyte of <600 kDa in Mw.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge that a portion of this work was supported by SBIR Grant R43-GM116663-01 from the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Fred Regnier and JinHee Kim are employed by Novilytic, LLC.

References

- 1.Boyles JS, Atwell S, Druzina Z, Heuer JG, Witcher DR. Protein Sci. 2016;25:2028–2036. doi: 10.1002/pro.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu X, Spada S, White S, Hudson S, Magner E, Wall JG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:18703–18709. doi: 10.1021/jp062423e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janis LJ, Grott A, Regnier FE, Smith-Gill SJ. J. Chromatogr. A. 1989;476:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)93872-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astefanei A, Dapic I, Camenzuli M. Chromatographia. 2017;80:665–687. doi: 10.1007/s10337-016-3168-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascini M, Guilbault GG, Monk IR, Hill C, Del Carlo M, Compagnone D. Microchim. Acta. 2008;163:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng X, Li Z, Podariu MI, Hage D. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:6454–6460. doi: 10.1021/ac501031y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reverberi R, Reverberi L. Blood Transfus. 2007;5:227–240. doi: 10.2450/2007.0047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lidofsky SD, Hinsberg WD, Zare RN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78:1901–1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubin PL, Kaplan JI, Tian B, Mehta M. J. Chromatogr. A. 1990;515:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 1988;11:1809–1826. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prazeres DMF. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1997;52:953–960. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfannkoch E, Lu KC, Regnier FE, Barth HG. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1980;18:430–441. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perraut C, Clottes E, Leydier C, Vial C, Marcillat O. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1998;32:43–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980701)32:1<43::aid-prot6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojtas M, Kaplon TM, Dobryszycki P, Ozyhar A. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;896:319–330. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3704-8_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson HP. Biol. Proced. Online. 2009;11:32–51. doi: 10.1007/s12575-009-9008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanderslice NC, Messer AS, Vadivel K, Bajaj SP, Phillips M, Fatemi M, Xu W, Velander WH. Anal. Biochem. 2015;479:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha RK, Gaiotto T, Bradbury ARM, Strauss CEM. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2014;27:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzu005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Müller-Späth T, Morbidelli M. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1060:331–351. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-586-6_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sviatenko OV, Gorbatiuk OB, Vasylchenko OA. Biotechnol. Acta. 2014;7:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nygren PA, Ljungquist C, Tromborg H, Nustad K, Uhlen M. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;193:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo J, Lee S, Poulter CD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8973–8980. doi: 10.1021/ja402447g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grodzki AC, Berenstein E. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;588:33–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-324-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docoslis A, Giese RF, van Oss C. Colloids Surf., B. 2000;19:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(00)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shmanai VV, Litoshko AA. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2001;74:1348–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dick JE, Hilterbrand AT, Boika A, Upton JW, Bard AJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:5303–5308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504294112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rathnasekara R, El Rassi Z. J. Chromatogr. A. 2017;1508:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima N, Ikada Y. Bioconjugate Chem. 1995;6:123–130. doi: 10.1021/bc00031a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchwalow I, Samoilova V, Boecker W, Tiemann M. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:28. doi: 10.1038/srep00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An analysis of the monoclonal antibodies market by source, type of production, indication, end-use and segment for 2013–2024. Grand View Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balm MND, Lee CK, Lee HK, Chiu L, Koay ESC, Tang JW. J. Med. Virol. 2012;84:1501–1505. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu AHB. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2006;369:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poole CF, Poole SK. J. Chromatogr. A. 2009;1216:1530–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyce MC, Haddad PR. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:2013–2022. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]