Abstract

Parent-child sex communication results in the transmission of family expectations, societal values, and role modeling of sexual health risk reduction strategies. Parent-child sex communication’s potential to curb negative sexual health outcomes has sustained a multidisciplinary effort to better understand the process and its impact on the development of healthy sexual attitudes and behaviors among adolescents. This review advances what is known about the process of sex communication in the U.S. by reviewing studies published from 2003 to 2015. We used CINAHL, PsycInfo and Pubmed, the key-terms “parent child” AND “sex education” for the initial query; we included 116 original articles for analysis. Our review underscores long-established factors that prevent parents from effectively broaching and sustaining talks about sex with their children and has also identified emerging concerns unique to today’s parenting landscape. Parental factors salient to sex communication are established long before individuals become parents and are acted upon by influences beyond the home. Child-focused communication factors likewise describe a maturing audience that is far from captive. The identification of both enduring and emerging factors that affect how sex communication occurs will inform subsequent work that will result in more positive sexual health outcomes for adolescents.

Parent-child sex communication is the bi-directional communication between parents (or parent figures) and their children about sex-related issues including sex, sexuality, and sexual health outcomes. Parents, through communication about sex in the home, have been identified as ideal sex educators because they are able to reach youth early to provide sequential and time-sensitive information that is responsive to the adolescent’s questions and anticipated needs (Krauss & Miller, 2012; Mustanski & Hunter, 2012). The sexual health of most adolescents and young adults is greatly influenced by the powerful role that parents play in children’s sexual socialization; the messages conveyed are influential in shaping adolescent sexual decision-making (DiIorio, Pluhar & Belcher, 2003).

Traditionally conceptualized as a verbal exchange between knowledgeable parents bestowing wisdom about sex to their uninitiated children, parent-child sex communication actually is a reciprocal process consisting of mothers, fathers and other caregivers interacting with daughters and sons. Whereas previous research tended to focus on parental concerns related to sexual behavior surrounding mostly negative outcomes (e.g., unplanned pregnancies, sexual abuse), recent scholarship has begun to explore more inclusive topics that children inquire about and deem pertinent (e.g., non-heterosexual identities, pleasure). And while most sex communication studies still predominantly document normative sex discussions performed along gender lines and role expectations, there has been a steady increase in research that investigates nuanced sex communication and topics (e.g., sexuality discussions around able-bodiedness, sexuality concerns of adolescents with chronic medical concerns).

The purpose of this review is to update what is known about the process of sex communication in the U.S. by reviewing studies published from 2003 to 2015. DiIorio, Pluhar and Belcher (2003) reviewed sex communication literature from 1980 to 2002 and identified three domains of research: 1) content and process, 2) predictors, and 3) behavioral outcomes. In the 12 years since that 2003 review, more U.S.-based studies that include novel theoretical and empirical findings have been published and now require critical analysis and synthesis.

Sex Communication and Adolescent Sexual Health Outcomes

The sustained research interest in sex communication is grounded in the relationship between parental provision of guidance about sex and the sexual health outcomes of youth. For example, parental warnings and discussions about sex were associated with condom use, decreased unprotected sex and increased protection from HIV and other sexually transmitted infections STIs (Harris, Sutherland, & Hutchinson, 2013; Hutchinson, 2007; Kapungu, Baptiste, Holbeck, et al., 2010; Teitelman, Ratcliffe, & Cederbaum, 2008). Nadeem (2006) found more explicit maternal conversations about condoms were associated with daughters’ detailed and accurate explanations of contraceptive knowledge, and Hadley (2009) identified that more discussions about condom use were associated with more protected sex acts. Additionally, greater self-efficacy in discussing sex with parents has been associated with greater condom use among adolescent males (Halpern-Felsher, Kropp, Boyer, Tschann, & Ellen, 2004).

The association between sex communication and adolescent sexual attitudes and health behaviors has also been well-documented. Sex communication with mothers was associated with more conservative adolescent attitudes towards sex and less perceived difficulty talking to partners about sexual topics (Hutchinson, 2007). Children who have been talked to by their HIV-infected mothers reported greater comfort talking about sex compared to their peers who had uninfected mothers (O’Sullivan, Dolezal, Brackis-Cott, Traeger, & Mellins, 2005). The more children perceived mothers talked about a topic, the more the adolescents endorsed that issue (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007). Furthermore, parental sex discussion about pubertal changes, intercourse and STIs was associated with daughters’ feeling prepared about bodily changes, availing human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines and adolescents testing for HIV (Clawson & Reese-Weber, 2003; Roberts, Gerrard, Reimer, & Gibbons, 2010).

Parents talking about sex with youth does not lead to sexual debut. In fact, adolescents who rate their general communication with parents favorably are less likely to be sexually active (Karofsky, Zeng & Kosorok, 2000). There is strong support that children who received messages to wait for marriage before sex were not as sexually active compared to those who were not given explicit instructions (Aspy et al., 2007; Sneed, 2008). Daughters were less sexually active when sex communication involved discussions of sexual values, where mothers related abstaining from sex for moral reasons to its potential effect on their daughters’ lives (Teitelman & Loveland-Cherry, 2004; Usher-Seriki, Bynum, & Callands, 2008). Fathers who provided information about how to resist pressure increased girls’ abilities to avoid being forced into sex (Teitelman, et. al., 2008). Moreover, mothers who are comfortable and responsive during sex communication were predictive of adolescents’ lesser likelihood of being sexually active, being abstinent, and being older at first intercourse (Fasula & Miller, 2006; Guzman et al., 2003). If youth were sexually active, they were more likely to use birth control (Aspy et al., 2006).

Despite the evidence linking sex communication with positive adolescent sexual behavior, these discussions in U.S. homes are fraught with well-established challenges and persistent concerns (DiIorio, Pluhar & Belcher, 2003). Our review will focus solely on the factors that affect the sex communication process; since DiIorio’s review, Akers, Holland, and Bost (2011) reviewed interventions that aimed to increase the frequency of sex communication; Sutton, Lasswell, Lanier, and Miller (2014) described interventions that used sex communication to impact sex and cognitive outcomes among minority youth; and Santa Maria, Markham, Bluethmann, and Mullen (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of parent-based adolescent sexual health interventions and its effects on communication outcomes. By focusing on study findings from the last 12 years, we were able to identify enduring factors that affect the process of sex communication and underscore areas of current and emerging research. The identification of both enduring and emerging factors that influence parents and children during sex communication will inform subsequent work that will result in more positive sexual health outcomes for adolescents.

Theoretical Framework

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory of Human Development (2006), henceforth Bioecological Theory, provides an encompassing approach to the study of an individual’s behavior, and in particular, a comprehensive lens to identify the multi-system factors that give rise to sexual health outcomes. The major concepts of the Bioecological Theory include process, person, context and time (the PPCT model).

First, process is the interaction between an individual and his or her immediate environment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) over time and is posited as “the primary mechanisms producing human development” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). For example, these reciprocal relationships include an adult explaining to a child where babies come from or parents and a teenage daughter discussing contraception use after menarche. Through these proximal processes individuals and the environment act on and shape each other (Tudge et al., 2009). Second, person pertains to the biopsychosocial characteristics of developing individuals that impact their capacity to influence proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Inherent in the person is their capacity to initiate and sustain relationships; their abilities, knowledge and skills essential for effective functioning; and their characteristics to invite or disrupt talks about sex. Next, context is the nested set of environments for which the Bioecological Theory is most famous. Conceptualized as four concentric circles centering on the developing person, context includes the microsystem, such as one’s parents, siblings, teachers and peers, who participate in the life of the person on a regular basis over an extended period of time; the mesosystem, the interrelations between the other microsystems such as the interaction of the home with churches or schools; the exosystem that includes societal institutions, such as media and local politics that have an important distal influence on human development; and the macrosystem, or the cultural context that encompasses groups whose members subscribe to shared beliefs, mores and customs. Finally, time refers to ongoing episodes of proximal processes that are spread across varying intervals such as days and weeks. This construct includes changing expectations and events in larger society, within and across generations over the life course (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

The Bioecological Theory will guide this literature review by examining sex communication as a proximal process that simultaneously affects parent and child attitudes and behaviors when talking about sex. The following research questions will be answered in this review: In the past 12 years: 1) What are the bioecological factors that influence the occurrence of this process? and 2) What are the enduring and emerging factors that affect sex communication?

Methodology

In order to systematically review the sex communication literature, we used a multi-step approach that included an exhaustive search strategy guided by a defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Afterwards, we inspected the initial search results, read the final articles, abstracted the data from individual studies and synthesized the findings according to factors that affect the process of sex communication. Tenets of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in this review (i.e. identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) (Moher, et.al. 2009).

Literature search strategy

A search was undertaken for all published articles about sex communication using the following electronic databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, PsycINFO and SocIndex. Key terms or controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH]) such as “parent-child relations,” “communication,” “sex education,” and “sexual behavior” were used for each database. Search sets were combined using Boolean operators (and, or, not). We consulted a Duke Medical Library health information specialist throughout the search of the online databases. A staged review was conducted (Torraco, 2005) which began with an initial review of the titles and abstracts, followed by an in-depth reading of each article that met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles identified through online databases had to meet the following conditions: 1) U.S.-based and published in a peer-reviewed journal, 2) with publication delimiters from January 2003 to December 2015, 3) published in English language journals, and 4) contained original findings from descriptive qualitative, quantitative or mixed method studies about the sex communication process. Sex in this review pertains to topics that parents talk about with their children, including developmental information about puberty, sexuality, and decision-making about sexual behavior. The articles accepted for inclusion were informed by the views of parent/s or children only or from parent-child dyads. Parents in these studies included biological, adoptive, foster, or custodial parents who are the guardians of the child/ren. Articles involving intervention research were excluded as these have been recently reviewed. Grey literature, systematic reviews and metasyntheses were also excluded. Articles that had a secondary finding or section on sex communication but whose main research questions were about other protective familial factors (e.g., parental monitoring, parent-child connectedness, general support) that also impact adolescent sexual behavior were excluded as were articles that measured sex communication frequency as one of many factors, and concurrently reported other adolescent behaviors (e.g., alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, and delinquency).

Search result

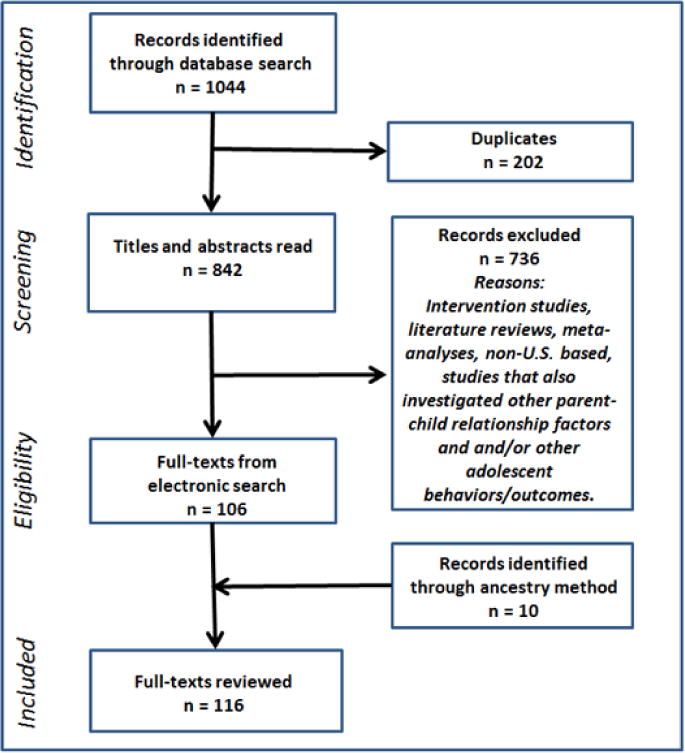

Our initial electronic search yielded 1,044 citations. Two hundred and two duplicates were removed and both authors screened the titles and abstracts to assess the relevance of the studies to the project. Of the remaining 842 articles, 736 references were excluded, leaving 106 full-text articles from the electronic search (see Figure 1). All reference lists were checked for pertinent citations that might not have been identified in the main online query of electronic databases. Through this ancestry method of cross-checking and back-referencing we ensured comprehensiveness (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Ten additional articles were identified from reference lists for a final count of 116 included studies. The accepted articles were exported to an EndNote library (Thomson Reuters, 2014) for data management. The authors individually conducted quality tests on the excluded articles, such as by skimming every tenth article to validate that these were correctly excluded. Further, if questions arose about an article’s ineligibility, the article was discussed until a consensus decision was reached.

Figure 1.

Literature Review Flow Search

Data Abstraction

The 116 articles accepted after the comprehensive search were abstracted through the matrix method (Garrard, 2013). An evidence table was created in Excel to organize information according to how it systematically informed the research findings. Column headings were based on study characteristics such as study design, setting, sample and methodology. DF independently abstracted findings from the eligible studies into the standardized matrices and this allowed the examination of the literature for contextual patterns and themes across studies.

Synthesis

An adaptation of framework synthesis (Carroll, Booth, & Cooper, 2011) scaffolded by Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory guided this review. This was accomplished by organizing the abstracted findings under broad groupings based on the PPCT model and informed by a priori themes from DiIorio and colleagues’ 2003 review. By using a relevant pre-existing framework merged with themes from the most recent review of sex communication, we were able to map and code data from the included studies. Throughout the analysis, similar and contradictory findings were noted as newer sex communication themes. Through this process, both the enduring and emergent bioecological factors that affect the process of sex communication were identified. Research implications of our findings are incorporated in the subsequent discussion section.

Findings

Methodological approaches

Table 1 provides the details of the studies included in this review. There was a similar number of qualitative (43%) and quantitative (45%) designs with the remaining using mixed methods (12%). A majority of studies (84%) used convenience sampling to identify participants. Most of the samples were Caucasian (22%), African American (23%), or came from diverse racial backgrounds (36%). Most of the studies included both children and parent samples (42%). There were more studies with mothers-only samples compared to studies with fathers-only samples (44% and 7%). Similarly, there were more studies with samples that only included daughters compared to studies with samples comprising of sons only (40% and 4%). Most of the children were high school and college age (36% and 23%).

Table 1.

Design and Sample Characteristics Across Studies

| Number (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| General Approach | ||

| Qualitative | 50 | 43% |

| Quantitative | 52 | 45% |

| Mixed methods | 14 | 12% |

| Total | 116 | 100% |

| Sampling Strategy | ||

| Convenience | 97 | 84% |

| Random within specific population | 13 | 11% |

| Nationally representative | 6 | 5% |

| Total | 116 | 100% |

| Race | ||

| >75% Caucasian | 25 | 22% |

| >75% African American | 26 | 23% |

| >75% Latino | 13 | 11% |

| >75% Asian | 6 | 5% |

| Racially Diverse/Multiethnic | 42 | 36% |

| Unknown | 4 | 3% |

| Total | 116 | 100% |

| Overall Sample | ||

| Children Only | 31 | 27% |

| Parents Only | 36 | 31% |

| Children-Parent Dyads | 49 | 42% |

| Total | 116 | 100% |

| Gender Composition of Parents | ||

| Mothers only | 37 | 44% |

| Fathers Only | 6 | 7% |

| Mothers and Fathers | 40 | 47% |

| Others | 2 | 2% |

| Total | 85 | 100% |

| Gender Composition of Children | ||

| Females Only | 32 | 40% |

| Males Only | 4 | 5% |

| Females and Males | 44 | 55% |

| Total | 80 | 100% |

| School Age Composition of Children | ||

| Pre-K to Grade 6 | 8 | 10% |

| Middle | 20 | 25% |

| High School | 29 | 36% |

| College | 18 | 23% |

| Not Specified | 5 | 6% |

| Total | 80 | 100% |

Process

According to the Bioecological Theory, processes are the interactions in which the parent and child are active participants who shape their environment, evoke responses and react to one another (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Darling, 2007). Parents and children engage in sex communication while riding in the family car, when watching TV, when considering whether to allow children to attend events such as sex education at school, and when discussing events involving family or friends (Eastman, Corona, Ryan, Warsofsky, & Schuster, 2005; Hannan, Happ, & Charron-Prochownik, 2009; Murray et al., 2014). During sex communication, numerous factors have been found as influential in the process including parent and child gender, the specificity of topics discussed, parents’ communication styles, tone, language, the focus on the consequences of sex, and its implications for the future. Ultimately, these factors result in a lack of congruence among sex communication reports.

Gender dynamics

Parent and child gender dynamics interact most strongly to predict sex communication, with most discussions occurring between mothers and daughters (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007; Kapungu, Baptiste, Holbeck, et al., 2010; Marhefka, Mellins, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Ehrhardt, 2009; Miller et al., 2009; Pluhar, DiIorio, & McCarty, 2008; Sneed, 2008; Wisnieski, Sieving, & Garwick, 2015). Across most of the literature, mothers figured more prominently than fathers in children’s sexuality education (Harris et al., 2013; Morgan, Thorne, & Zurbriggen, 2010; Raffaelli & Green, 2003; Sneed, Somoza, Jones, & Alfaro, 2013; Wilson, Dalberth, & Koo, 2010). The number of topics discussed is highest between same-gender dyads, where daughters receive significantly more sexual health discussions from their mothers than fathers (Kapungu, Baptiste, Holbeck, et al., 2010; Raffaelli & Green, 2003; Swain, Ackerman, & Ackerman, 2006), and sons received more from their fathers than mothers (Tobey, Hillman, Anagurthi, & Somers, 2011). Still, some studies contradict that general trend and found that sons reported an equal amount of information about sex communication from both parents (Wyckoff et al., 2008) or in one case, more sons than daughters discussed sex with mothers (Sneed et al, 2013).

General versus specific topics

Parents emphasize general communication about sex rather than engaging in talks about specific topics (Eisenberg, Sieving, Bearinger, Swain, & Resnick, 2006; Kapungu, Baptiste, Holbeck, et al., 2010; LaSala, 2015; Sneed, 2008). For example, parents tended to focus more on informational topics such as warnings about STIs and HIV protection rather than discussing personal topics such as asking if children were having sex (Sneed et al., 2013). Even mothers with HIV infection are more likely to discuss HIV prevention, but not sex or birth control (Marhefka, Mellins, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Ehrhardt, 2009). In a qualitative study involving mother-child dyads in New York City, mothers expressed relative comfort and willingness to discuss the consequences of sex, but not specific, fact-based information regarding intercourse and birth control (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006).

Further, talks about sexual decision-making were supported more than discussions about emotions, relationships and romance (Stiffler, Sims, & Stern, 2007; Wisnieski et al., 2015).

Parental communication style

Although parental directness facilitates sex communication, the findings are mixed when it comes to who engages in this communication style. In general, lack of parental communication skills causes children to avoid and be anxious about sex discussions, while parents who can communicate with their children share and discuss their life experiences with minimal reservation (Afifi, Joseph, & Aldeis, 2008). The directive communication style, which includes parents being forthright in the provision of clearly stated expectations about sex and unambiguous about their preference for children’s behavior, are associated with positive parent-child relationships and less risky sexual behavior (Peterson, 2007; Sneed, 2008). However, another study found that directive parents who tend to have a more authoritarian communication style do not invite open discussion and questions from children (Heller & Johnson, 2010). Few fathers provide explicit guidance (Solebello & Elliott, 2011); those who were willing to have in-depth, open and honest conversations contributed to daughters’ knowledge, ability to clarify, and knowledge that they could talk to fathers about sex any time (Nielsen, Latty, & Angera, 2013). Many mothers were blunt about sex and honest in their approach (Murray et al., 2014), while others were avoidant or reticent (Baier & Wampler, 2008; Pluhar, Jennings, & DiIorio, 2006). Daughters agreed that mothers’ candidness contributed to communication about sexual risks (Cederbaum, 2012; Cox, Mezulis, & Hyde, 2010). Interactive communication strategies include making sure adolescents’ voices are heard to encourage active exchange of questions and answers, assessing current knowledge and leaving room for future discussions (Edwards & Reis, 2014).

Tone and language

Daughters discussed how a parent’s negative emotional tone affected their ability to talk about sex, while a positive tone lead to further discussions about sex (Aronowitz & Agbeshie, 2012). Fathers who are good sex educators were thorough and their tone communicated clearly the seriousness of the topic, while fathers who are not as effective broached sexuality in vague, nonspecific ways that left daughters wondering what parents were trying to communicate (Nielsen et al., 2013). Parents sometimes used veiled language (Aronowitz & Agbeshie, 2012) and discussions about sex often included the use of euphemisms (Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Pluhar et al., 2006). In a study involving grandparents as sex educators, their unfamiliarity with slang and sexual lingo used by teenagers did not facilitate sex communication (Cornelius, LeGrand, & Jemmott, 2008). Further, children as young as 4 years old preferred slang words over parents’ use of anatomical terms (Martin & Torres, 2014).

Consequence-focused discussions

Studies indicate that parents framed the sex discussions in terms of consequences and cautionary statements, with the underlying message often being sexually prohibitive (Afifi et al., 2008; Akers, Schwarz, Borrero, & Corbie-Smith, 2010; Cox, Scharer, Baliko, & Clark, 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2006; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Kim & Ward, 2007; Meschke & Peter, 2014; Nappi, McBride, & Donenberg, 2007). Parents conveyed clear disapproval of their children engaging in sex (Jaccard, Dodge, & Dittus, 2003), and they underscored the negative outcomes of sex (Heisler, 2005; Stauss, Murphy-Erby, Boyas, & Bivens, 2011), which for them can ruin children’s lives (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006). Fear was regularly employed to persuade daughters to be abstinent (Pluhar & Kuriloff, 2004) and parents routinely talked about the repercussions of sex and the risks of pregnancy, disease, and victimization (Elliott, 2010b; Gilliam, 2007; Teitelman, 2004). The threat of sexual abuse is another topic often brought up that further discouraged any positive discussions about sexuality (El-Shaieb & Wurtele, 2009). Pleasure or the positive aspects of sex was off limits; sex positivity was not addressed (Aronowitz, Todd, Agbeshie, & Rennells, 2007b; Elliott, 2010a; Hertzog, 2008). From adolescents’ perspectives, sex communication was essential to prevent risky sexual behavior (Cornelius, LeGrand, & Jemmott, 2009), but they dismissed scare tactics as ineffective sex communication (Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004).

Future orientation

For a lot of parents, conversations with children about abstinence, pregnancy and delaying sex were related to future success. Sex communication in these households emphasized the future in terms of prioritizing educational goals (McKee & Karasz, 2006) and attaining self-sufficiency through gainful employment before supporting a family (Akers et al., 2010; Meschke & Peter, 2014; Murray et al., 2014). In these talks about the future, sex and unplanned pregnancies were depicted as a threat that forced children to grow up early (Afifi et al., 2008) and can be an impediment to achieving one’s dreams (Jaccard et al., 2003).

Incongruence of reports

There remains a marked incongruence between parent and adolescent reports of the frequency of sex communication. Parents typically remembered more incidents of having the sex talk while children reported fewer recollections (Chung et al., 2007; Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Hadley et al., 2009; LaSala, 2015; Miller, Ruzek, Bass, Gordon, & Ducette, 2013; Nappi, McBride, & Donenberg, 2007; O’Sullivan et al., 2005). Between grandparents and grandchildren, there was a more pronounced incongruence about which sex topics were discussed (Cornelius et al., 2008). However, preadolescents and their parents agreed about the occurrence of sex communication (Wyckoff et al., 2008) and topics discussed during childhood and into adolescence (Beckett et al., 2010). Similarly, incongruence was also reported among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and sex talks with their parents, where parents did not report any barriers to talking about health and sexual orientation with their sons, while the opposite was reported by the YMSM (Rose, Friedman, Annang, Spencer, & Lindley, 2014).

Reciprocal reluctance to initiate conversations

When mothers provided information and feedback, daughters were more engaged and desired further conversations about sex (Mauras, Grolnick, & Friendly, 2013). However, most mothers admitted they only discussed sex-related issues at their daughters’ initiation and they did not talk about sex unless asked (Baier & Wampler, 2008; Elliott, 2010a). Parents believed their children would approach them if they have questions, while children reported they were unlikely to do so even if they had concerns (Collins, Angera, & Latty, 2008; Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004). Daughters reported not knowing how to initiate conversations about sex and looked to their mothers to start the sex communication process (Dennis & Wood, 2012). Further, parents of gay and bisexual youth wished their sons would bring up sex topics if they have any questions, but the youth reported being reticent and wished parents would take the first step (LaSala, 2015). Similarly, most Muslim mothers did not think it was necessary to initiate conversations and said they were available if daughters need to talk (Orgocka, 2004). Additionally, some parents thought it was almost like an assault if they were too forceful or too open about sex (McKee & Karasz, 2006).

Person

When viewing sex communication through the Bioecological Theory, children are conceptualized as more than passive recipients of knowledge. Children bring with them developmental attributes, temperaments and predispositions that impact how parents broach sex-related issues. Likewise, parents’ interactions with children involve their own experiences, ideas and values that trigger specific reactions from children. The following child and parent attributes have been identified as salient person centered factors that impact sex communication.

Child Attributes

A child’s age and their perception that initiating conversations about sex would elicit a negative reaction from parents are the two main child-centered attributes that affect sex communication.

Age

There is ample evidence that the child’s age is a significant predictor of sex communication. Current age of the daughter predicted timing of first discussions about sex (Askelson, Campo, & Smith, 2012; Miller et al., 2009b), and sex communication occurs earlier with daughters than with sons (Beckett et al., 2010). Parents are less likely to talk with younger teens about sex (Swain et al., 2006), and they reported discussions to be more challenging with younger rather than older daughters (Coffelt, 2010). Parents are more inclined to talk about sex when they deem their child as mature, which can explain why older adolescents received more communication than younger children (Lefkowitz, Boone, Au, & Sigman, 2003; Pluhar et al., 2008; Tobey et al., 2011). Nevertheless, it has also been reported that children’s age was not associated with sex communication between mothers and daughters (O’Sullivan et al., 2005).

Anticipated disapproval

Generally, adolescents could not discuss topics of a sexual nature with their parents out of fear that they may be viewed as sexually active and face punishment (Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006). Fear, based on the assumption that parents would judge them – that mothers think, “if she’s talking about it, she’s doing it” (Pluhar & Kuriloff, 2004) – keeps children from engaging in sex communication about a variety of topics (Dennis & Wood, 2012; Eastman, Corona, Ryan, Warsofsky, & Schuster, 2005a; Sisco, Martins, Kavanagh, & Gilliam, 2014). Daughters’ fears of relationship strain, anticipated loss of trust, and beliefs that mothers are not open to hearing information about their sex-related concerns, caused reluctance to ask about sex (Cederbaum, 2012). Furthermore, among adolescents whose parents disclosed to them their HIV-infected status, the fear of upsetting or reminding parents of their serostatus prevented some children from talking about sex (Corona et al., 2009).

Parent Attributes

Factors identified from the literature that exclusively affect parents’ capacity to discuss sex with children include their low levels of knowledge about sex, a commitment to become better sex educators for their children than their parents were for them, leveraging traumatic experiences as impetus to talk about sex, viewing sex talks as permission for children to have sex, and a perception that their children are not old enough for sex communication.

Knowledge deficit

Parents have varying levels of knowledge about sex-related topics, with most of them having an inadequate base of information (Heller & Johnson, 2010; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Martin & Torres, 2014; Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Pluhar et al., 2006). For instance, in a study about family planning discussions, contraceptive knowledge was low for parents and they had minimal information about risks and side effects (Akers et al., 2010). Fathers in Atlanta supported the view that as sex educators they did not have subject matter expertise (DiIorio et al., 2006). For mothers, many professed inadequate knowledge about male sexuality (Cox et al., 2010), and they relied on male figures to address those questions (Murray et al., 2014; Pluhar et al., 2006). Single mothers, for example, limited sex communication out of concern that they might impinge on their son’s development of a normative masculine and heterosexual identity (Elliott, 2010a). Adolescents concurred and attributed the lack of sex communication to parents not being knowledgeable about sex-related topics (Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Gilliam, 2007). Denes and Afifi (2014) found that for many gay, lesbian, bisexual and queer individuals, disclosing their sexuality to parents a second time was necessary to share more information about themselves and address parents’ lack of understanding about what being a sexual minority was about. Further, parents’ lack of knowledge about the health issues that YMSM contend with was reported to be a barrier to parent-child sex communication (Rose et al., 2014).

Doing better than their parents

Due in part to the perceived parental lack of knowledge about sex observed when they were growing up, the parents included in the review reported a need to be better sex educators for their own children. Parents viewed their own parents as ineffective sexuality educators (Kenny & Wurtele, 2013); they did not have parents who modeled how to have these conversations effectively (Eastman et al., 2005). Parents attributed their lack of preparedness for sex communication to their own dismal experiences with the process (Eastman et al., 2005; Lehr, Demi, DiIorio, & Facteau, 2005; McKee & Karasz, 2006; McRee et al., 2012; Noone & Young, 2010). According to DiIorio et al (2006), some parents’ negative feelings about their own experiences with sex communication a generation earlier often serve as an impetus to provide better sex education for their children. Parents want “to do better than their parents had done with them,” (p. 460) (Ballard & Gross, 2009; LaSala, 2015) and they intended to discuss sex when their children are younger compared to when they themselves were taught about it or when they were forced to contend with sexual silence (Alcalde & Quelopana, 2013; El-Shaieb & Wurtele, 2009; Kenny & Wurtele, 2013). Muslim mothers, for example, saw sex communication as an important duty to offer moral and emotional support to daughters, based on their own experiences lacking parental models (Orgocka, 2004).

Learning from traumatic experience

Parents’ own experiences with risky sexual behavior when they were adolescents triggered discussions about sex-related issues with their own children (Grossman, Tracy, Richer, & Erkut, 2015; Noone & Young, 2010; Williams, Pichon, & Campbell, 2015). Broaching sex-related issues was motivated by concerns over victimization of vulnerable children, such as those with autism spectrum disorders (Ballan, 2012; Holmes & Himle, 2014), or stemming from their own personal trauma such as experiences with sexual abuse or interpersonal violence (Akers, Yonas, Burke, & Chang, 2011; Deblinger, Thakkar-Kolar, Berry, & Schroeder, 2009; Woody, Randal, & D’Souza, 2005). For HIV-infected mothers, sex communication involved taking a negative experience and creating a positive teaching opportunity (Cederbaum, 2012; Corona et al., 2009; Murphy, Roberts, & Herbeck, 2012). Mothers living with HIV were more comfortable and more likely to report discussing HIV and related sexuality topics compared to mothers without HIV (O’Sullivan et al., 2005).

Acknowledgement of parental responsibility

Parents acknowledged it is their responsibility to teach their children about sex (Ballan, 2012; Elliott, 2010a, 2010b; Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Dittus, & Collins, 2008; Regnerus, 2005; Stiffler et al., 2007). Sex communication is viewed as an opportunity for parents to educate not only about sexuality, but also the effects of children’s sexual behavior on their overall health (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Hannan et al., 2009; Hutchinson & Cederbaum, 2011). Fathers wanted to instill a sense of responsibility so that their sons can learn from their stories and be trusted to make the right choices to protect themselves from negative consequences such as STI (DiIorio et al., 2006; Ohalete, George & Doswell, 2010). Despite fathers having lower self-efficacy and lower expectations that sex communication would have positive outcomes (Wilson, Dalberth, & Koo, 2010), they believe sex communication is an ongoing process that should start at a young age and continue throughout adolescence (Lehr et al., 2005). In particular, some fathers provide the male perspective for their daughters (Solebello & Elliott, 2011). Nevertheless, parental responsibility for children’s sex education was not shared by all parents. From a group of parents who were in college, Heller and Johnson (2010) found that many of them did not feel any urgency to cover discussions about condoms and HIV/AIDS due to public schools discussing those topics with their children; also, some fathers view sex education as part of a mother’s responsibility (Collins et al., 2008).

Sex communication as a green light to have sex

Parents are concerned about sending mixed signals when discussing sex with children and fear that the information might be misconstrued as permission to have sex and promote adolescent sexual activity (DiIorio et al., 2006; Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Wilson, Dalberth, Koo, & Gard, 2010). For parents, including the positive aspects of a sexual relationship during sex communication might lead to risky sexual behavior and be perceived as a “green light” to have sexual intercourse (Aronowitz et al., 2007; McKee & Karasz, 2006). In several studies, parents struggled to promote abstinence and feared sex discussions might increase curiosity and encourage sexual experimentation (Aronowitz et al., 2007; Elliott, 2010a; Ohalete, Georges & Doswell, 2010). However, contrary to these parents’ concerns, grandparents in another study believed that talking about sex does not encourage sexual activity (Cornelius et al., 2008).

Children being too young

Many parents think children are too young for sex information and have difficulty acknowledging their children’s sexuality (Deblinger et al., 2009; Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Noone & Young, 2010). For instance, mothers of elementary age children often did not associate sexuality and sexual development with their 6-10 year olds, and therefore felt they would not be ready when asked about sex by their children (Pluhar et al., 2006). Additionally, according to daughters, fathers viewing them as “Daddy’s little girl” inhibited sex communication (Hutchinson & Cederbaum, 2011). Further, parents express ambivalence and disagree about when, what, and how much to say to their children about sexual topics (Cornelius, Cornelius, & White, 2013; Elliott, 2010a). However, not everyone is reticent about broaching sexuality. Parents can and do talk about sexuality issues with young children and preadolescents (Miller et al., 2009; Wilson, Dalberth, Koo, et al., 2010; Wyckoff et al., 2008).

Context

Bronfenbrenner described context as the nested set of environments that affect the developing individual. Distinct contextual patterns have been identified in the literature and can be classified according to the four concentric circles of the Bioecological Theory (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ecological Factors that Impact PCSC Sex Communication

| Ecological Level | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Microsystem | ||

| Adolescent milestones as cues | Parents use observable pubertal changes and children’s emerging sexual or romantic interests during adolescence as cues to initiate conversations about sex. Parents wait until their children are physically mature, as evidenced by breast development or menses, before initiating sex communication. For example, sex communication is triggered when daughters become more inquisitive about boys or after observing their son’s physical development or only after parents believed their children were sexually or romantically involved. Moreover, parents are less likely to talk with teens they believed are not romantically involved. Social milestones used as a reminder to discuss sex and developmental changes include times when children begin having sex education classes in school and when discussing preventive sexual health issues on general such as HPV vaccines. | Askelson et al., 2011; Cox, Scharer, Baliko, & Clark, 2010; Eisenberg, Sieving, Bearinger, Swain, and Resnick, 2006; Hannan, Happ, & Charron-Prochownik, 2009; Lehr, Demi, Dilorio, & Facteau, 2005; Marhefka, et.al., 2009; McRee et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2009; Ohalete, 2007; Swain, Ackerman, & Ackerman, 2006a |

| Closeness and comfort level | The closeness and comfort level adolescents have with parents is associated with sex communication. More sex communication is associated with greater parent-child closeness. Further, greater parent comfort with sex communication explains direct guidance, such as face-to-face discussions, and a higher number of sex topics discussed. Additionally, parental comfort in discussing general and specific topics increases over time. Approachability and responsiveness also affects sex communication. Mothers who are approachable foster trust and are able to assess daughters’ readiness to talk. Mothers with the highest responsiveness had significantly increased odds of discussions about abstinence, puberty, and reproduction. Meanwhile, paternal discomfort is interpreted as a lack of caring or being judgmental of children’s thoughts or actions, and keeps daughters away. | Boyas, Stauss, & Murphy-Erby, 2012; Corona et al., 2009; DiIorio et al., 2006; Fasula & Miller, 2006; Guzman et al., 2003; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; Martin & Luke, 2010; McRee et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2009; E. M. Morgan, A. Thorne, & E. L. Zurbriggen, 2010; Nielsen, Latty, & Angera, 2013; Noone & Young, 2010; Pluhar, DiIorio, & McCarty, 2008; Solebello & Elliott, 2011; Woody, Randal, & D’Souza, 2005 |

| Embarrassment | For a majority of parents, discussions about sex are associated with embarrassment. Despite being cognizant of the need to address sex with their children, parents anticipate a conversation that will cause frustration and discomfort for both parties. Even among a group of urban-dwelling parents with advanced educational degrees, the embarrassing notion of someday discussing sex with their children is identified as potentially getting in the way of sex communication. Adolescents too are generally dismissive of parents’ attempts to discuss sex and are also embarrassed by the exchange. Sons joke and employ sarcasm with their parents during these talks while daughters admit that discussing sex with their parents is avoided. Overall, older adolescents tend to display higher levels of negative affect than younger children when probed by their mothers about sexuality matters. | Afifi, Joseph, & Aldeis, 2008; Ballard & Gross, 2009; Cox et al., 2010; DiIorio et al., 2006; Eastman, Corona, Ryan, Warsofsky, & Schuster, 2005; Elliott, 2010b; Fitzharris & Werner-Wilson, 2004; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006; Jerman & Constantine, 2010; McKee & Karasz, 2006; Meneses, Orrell-Valente, Guendelman, Oman, & Irwin, 2006; Noone & Young, 2010; Romo, Nadeem, Au, & Sigman, 2004; Rose, Friedman, Annang, Spencer, & Lindley, 2014; Wilson & Koo, 2010 |

| Extended family members | Parental silence is a roadblock that results in other family members stepping in and becoming resources for sex. Children sometimes opt to talk to aunts and grandparents. Stepmothers are seen as less judgmental, more accepting, and less inclined to worry when compared to their own mothers. Further, familismo among Latino families allow adolescents to discuss sexual issues with extended family members, including talks about romance. | Cornelius, LeGrand, & Jemmott, 2008; Crohn, 2010; Guzman et al., 2003; Pluhar & Kuriloff, 2004; Wisnieski, Sieving, & Garwick, 2015 |

| Mesosystem | ||

| Parental Education | Parental education is positively associated with sex communication; discussions are more likely to occur with mothers who have a college degree or parents with more formal schooling. More educated Latina mothers probe more about children’s sexuality-related activities and questions, while paternal education predicted sex communication with both Latino sons and daughters. Nevertheless, fathers with less education have also been reported to engage in more sex communication. | Kim & Ward, 2007; Lefkowitz, Boone, Au, & Sigman, 2003; Lehr et al., 2005; McRee et al., 2012; Raffaelli & Green, 2003; Romo et al., 2004; Stidham-Hall, Moreau, & Trussell, 2012 |

| Religiosity | There are mixed results about the role religion plays in how conversations about sex are framed. Several reports support the idea that religion impacts sex communication. In rural South Carolina, mothers used faith-based messages with their children where “biblical instruction should be sufficient to prevent the adolescent from engaging in sexual activity,” p. 189, (Cox et al., 2010). Less religious mothers initiate sex communication earlier compared to their religious counterparts and parents in the southern U.S. are receptive to faith-based and church-led sex discussions with their children. Regnerus (2005) found that higher parental religiosity was linked to fewer discussions and greater unease in talking about sex. Further, religious affiliation and church attendance contributed to less frequent conversations about birth control and were associated with more discussions about the moral implications of adolescent sexual activity. Adolescents who discussed safer sex with their parents reported less church attendance compared to their peers who did not discuss safer sex, but attended church more frequently. However, there are a handful of studies that do not link religiosity and parent-child sex communication where reports of religiosity did not determine the amount of time Latina mothers talked both implicitly and explicitly about abstinence and contraceptive use, despite being Catholic. | Afifi et al., 2008; Baier & Wampler, 2008; Cornelius, Cornelius, & White, 2013; Cox et al, 2010; El-Shaieb & Wurtele, 2009; Hertzog, 2008; Lefkowitz et al., 2003; Nadeem, Romo, & Sigman, 2006; Ohalete, Georges, & Doswell, 2010; Pluhar et al., 2008; Regnerus, 2005; Romo, Bravo, Cruz, Rios, & Kouyoumdjian, 2010; Swain et al., 2006; Williams, Pichon, & Campbell, 2015 |

| Exosystem | ||

| Mass Media | Mass media emerged as the most influential factor in the exosystem and its impact occurs in two distinct ways. First, the perceived negative effects of highly sexualized media content on impressionable minds compel parents to discuss sex-related issues with their children. Even among parents who found it challenging to verbalize their concerns about sex, a form of indirect sex communication included restricting media use by Asian American children to convey disapproval of Western sexuality. Second, many parents used examples from TV as opportunities to broach sex-related issues. For example, in a study about how mothers discuss sexuality with daughters born with Type 1 Diabetes, mothers recalled addressing reproductive health when sexually explicit content appeared on TV. Similarly, the internet has been used by parents to assist their children to find sexuality-related resources to complement discussions they had about sex. | Aronowitz, Todd, Agbeshie, & Rennells, 2007; DiIorio et al., 2006; Eastman et al., 2005; Edwards & Reis, 2014; Hannan et al., 2009; Kim, 2009; McRee et al., 2012; Noone & Young, 2010; Pluhar & Kuriloff, 2004 |

| Macrosystem | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | Race and ethnicity affects how sex communication occurs in various ways. In a diverse sample of adolescents from the Midwest, Caucasian children reported more sex communication when compared to African American and Latino/Hispanic children. African American adolescents received significantly more paternal communication than Caucasians did, and Caucasians received more sex communication from fathers than Hispanic adolescents did. Data from a national study found that Asian and Latina mothers reported the most infrequent amounts of sex communication. Among Asian families, mothers, more than fathers, are the sources of sexual information, but there is also a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in which both parties avoid communication about sex to avoid tension. Parents of Latino children tend to use direct rather than indirect communication about sexuality. Discussing sex as improper was associated with less perceived openness in general communication by both Latina mothers and daughters. On the contrary, tener confianza (“instilling confidence”) observed among Latino parent-child dyads underscores confiding in parents and seeking their advice, keeping information confidential and having non-punitive responses to children’s disclosures. Among Asian American children, indirect sex communication included gossiping to convey sexual values along with imposing rules that constrained how daughters dress and socialize. Cultural differences between immigrant parents and their U.S.-born children that impede sex communication are consistently noted, with more adolescent acculturation predicting less frequent discussions about sex. For example, the varying ability of parents to speak to their children in English or the conservative upbringing of Latina mothers clash with children’s sexual mores. In Asian American families, a cultural divide caused both groups to withdraw from family communication about sex to avoid conflict and preserve harmony. Nonetheless, migrating to the U.S. has also been pointed out by fathers as causing a transformation in traditional views about children’s sexuality. |

Chung et al., 2005; Chung et al., 2007; González-López, 2004; Kim & Ward, 2007; McKee & Karasz, 2006; Meneses et al., 2006; Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Murphy-Erby, Stauss, Boyas, & Bivens, 2011; Orgocka, 2004; Raffaelli & Green, 2003; Romo, Bravo, Cruz, Rios, & Kouyoumdjian, 2010; Sneed, 2008; Somers & Vollmar, 2006; Tobey, Hillman, Anagurthi, & Somers, 2011 |

| Gendered Content | There are differences in what parents tell males compared to what they tell females during sex discussions. Females are held to a stricter moral standard compared to males. Daughters recalled discussing delaying sex until marriage while more males discussed condom use. Similarly, college-aged women remembered receiving restrictive sex messages, including warnings about the opposite sex, while young men received positive sex messages, including the inevitability of sex before marriage. According to parents, daughters have to value themselves in order to avoid being taken advantage of, while sex communication with sons are more about taking responsibility for behaviors and treating women with dignity and respect. Fathers wanted to teach their sons to grow up heterosexual by modelling masculine behavior and giving tacit permission when sons are caught watching pornography. Among Asian and Latino families, parents are explicit about their expectations for their daughters’ dignified behaviors out of concern for family reputation while sons do not receive the same messages. | Akers, Schwarz, Borrero, & Corbie-Smith, 2010; Akers, Yonas, Burke, & Chang, 2011; Aronowitz et al., 2007; Averett, Benson, & Vaillancourt, 2008; Brown, Rosnick, Webb-Bradley, & Kirner, 2014; Dennis & Wood, 2012; Elliott, 2010a; Gilliam, 2007; González-López, 2004; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2006; Heisler, 2014; Kapungu et al., 2010; Kim & Ward, 2007; Martin & Luke, 2010; Morgan, Thorne, & Zurbriggen, 2010; Murphy-Erby et al., 2011; Sneed, Somoza, Jones, & Alfaro, 2013; Solebello & Elliott, 2011; Stauss, Murphy-Erby, Boyas, & Bivens, 2011; Wilson & Koo, 2010 |

| Socioeconomic Status | A family’s socioeconomic status influences the content of sexual communication. Low income minority parents reported more discussion about the negative consequences of sex and where to obtain birth control, compared to higher income Caucasian parents. Scripts explicitly about postponing sexual intercourse or involvement in a relationship are recalled mostly by low income girls, while girls from higher income households have fewer explicit discussions about sexual risks, but more conversations about good decision-making and life opportunities. Similarly, Latina mothers from a lower socioeconomic background talked more to their daughters about avoiding risky situations and engaging in self-protective practices, while those with a higher socioeconomic status had longer discussions about positive sexuality, and contraceptive use. | Romo et al., 2010; Swain, Ackerman, & Ackerman, 2006b; Teitelman & Loveland-Cherry, 2004 |

Time

Frequency and consistency of sex communication play a crucial role in how this proximal process simultaneously affects parents and their children.

Frequency and consistency

Most discussions in the US about sex are episodic or one-time events that are punctuated by frustration and unease (Aronowitz & Agbeshie, 2012; Aronowitz et al., 2007; Averett et al., 2008; Baier & Wampler, 2008; Coffelt, 2010; Cornelius et al., 2009; Cornelius et al., 2013; Dennis & Wood, 2012; Meschke & Dettmer, 2012; Orgocka, 2004; Wilson & Donenberg, 2004). Fathers conducted ‘spot-checks’ and assumed their children received information from other sources (Solebello & Elliott, 2011). However, other studies report that continuous sex communication occurs in some households. For example, daughters reportedly received more instructive information from fathers when they were younger, and over time these conversations evolved into collaborative and open dialogues (Collins et al., 2008). Further, in a longitudinal study with college-aged young adults, there was more open and comfortable sex communication with parents noted during students’ senior years compared to when they were freshman (Morgan et al., 2010). Finally, patterns across time showed that while sons received the same number of talks about birth control methods from the 1980s to early 2000s, the same was not the case for daughters (Robert & Sonenstein, 2010). Specifically, longitudinal data from national surveys showed that fewer daughters had a conversation about STDs or birth control in 2002 than they did in 1995 (Robert & Sonenstein, 2010).

Discussion and Recommendations

The parent-child relationship during adolescence shifts from unilateral parental authority to one that is cooperative and negotiated (Steinberg, 2015). However, numerous individual factors coupled with contextual influences act on parents and children to make sex communication a complicated process that is far from cooperative and negotiated. A handful of these bioecological factors are enduring issues related to the sex communication process and have been previously identified by DiIorio et al. (2003). These include awkwardness and discomfort, reciprocal reluctance, and gender dynamics and gendered content. Twelve years after the DiIorio review, several emergent issues have been identified and demand further scrutiny. Among them is the role of a redefined family, nonverbal cues during sex communication, a focus on specific adolescent subpopulations, and the ubiquity of new media.

Enduring Sex Communication Issues

Awkwardness and timing concerns

By and large, the perennial awkwardness and discomfort noted as a defining attribute of the process is due to the reactive and one-time nature of these sex conversations. Often triggered by developmental cues, conversations about sensitive topics – especially when no prior talks precede it – can be perceived by adolescents as awkward, intrusive, or forced. Additionally, at a time when they are simultaneously adapting to their changing bodies, labile emotions, and asserting independence, ill-timed sex communication comes across as confrontational. It is therefore crucial to understand the timing of sex communication. Morgan and colleagues (2010) reported a change in conversations over time between parents and college-age children from previously unilateral and restrictive talks about sex to more reciprocal discussions characterized by mutuality. Longitudinal comparative studies that explore timing issues with pre-adolescents must be conducted to more fully understand how sequential and developmentally appropriate conversations can be achieved. A better understanding of the evolving parent-child relationship with regard to sex topics that are deemed age-appropriate can counter the universal embarrassment felt by parents and adolescents that is a substantial barrier when discussions about sex do occur.

Reciprocal reluctance

Many parents truly expect their children will approach them for guidance when they have questions about sex, but children also expect parents to initiate these conversations. This waiting game undercuts the potential of sex communication as a proximal process to influence the sexual development of children and perpetuates the cycle of silence that is observed from one generation to the next. Given that parental comfort in discussing general and specific topics increases over time, studies about broaching developmentally appropriate sex communication at earlier ages are recommended. Investigating sex communication starting at the pre sexual stage can yield a better understanding of the reciprocal and evolving dynamics between parents and children and the contexts that determine adolescent behavior and attitude at later sexual stages.

Gender dynamics and gendered content

The literature has affirmed that parent and child gender is an important factor during sex communication. Findings also revealed the general pattern that when sex communication happens, the marked differences in content conveyed to girls and boys reinforce gender stereotypes. A battle of the sexes mentality is the prevailing approach perpetuated by parents who both admonish sons against aggressive girls and daughters against opportunistic boys. The attempt to reduce adolescent sexual risks through sex communication in the last 12 years in many U.S. households, particularly in minority and low socioeconomic status families, is therefore based on an adversarial approach that is founded on mistrust and that does not encourage factual learning about potential sex partners. To address this, the unanimity of parents’ desire to equip children with knowledge or skills for a successful future can be leveraged and necessitates studies that will examine and challenge parents’ perpetuation of gender bias and sexual stereotypes. Gendered messages around sex must be investigated to encourage meaningful re-conceptualizations of equal and consistent sex messages for daughters and sons.

Mothers as de facto sex educators

The findings that mothers are overwhelmingly cited in most studies as the primary sex educator in U.S. homes is not a surprise. Mothers are consistently noted as more proactive in broaching sex talks, they cover more topics, and they exhibit more comfort when discussing sex compared to fathers. The finding that mothers are more comfortable engaging with daughters than sons in sex communication also supports the gendered sex communication noted above. This difference in comfort with sex communication based on parents’ gender can be explained in part by a large survey of mothers with young children that found that mothers do not care as much about daughters seeing them naked compared to sons, which provides more early opportunities to talk about bodies and sexuality among mothers and daughters (Martin & Luke, 2010). While seemingly simplistic, these early dyadic exchanges do set a pattern for more mother-daughter discussions that continue through adolescence and beyond. Additionally, the comfort level in talking about sex with children that is associated with mothers more than with fathers has resulted in the burden of sex education falling mainly within mothers’ purview. Compounded by the fact that caregiving responsibilities are still viewed as part of mothers’ domain, as evidenced by the fact that mothers usually are heads of household for most single-parent families in the U.S., the responsibility for sex education remains lopsided. Finally, when related to the findings that sex communication is simultaneously future- and consequence-oriented, that engaging in sex early almost certainly has ramifications, pressure on daughters to be gatekeepers of sex, and their mothers who have to make sure that daughters are forewarned, are reinforced so as not to undermine their future prospects.

Paternal roles

Children view their fathers as having inherent authority regarding specific topics, such as how males think, and children would prefer learning about such topics from their fathers. However, only 7% of the studies reviewed here included father-only samples compared to the 44% that involved mother-only participants. The study of fathers’ sex communication support needs is paramount to improve paternal engagement in sex communication. Specifically, the role of residential versus non residential fathers and the increasing number of stay-at-home fathers (Rehel, 2014) merit further attention for paternal sex communication. Despite parents favoring an ideal scenario where they present a united parental front (Ballard & Gross, 2009), no information is available on how shared custody affects the sexual socialization of children. Sex communication involving parents with strained relationships has not been studied to determine how topics and values are shared with children who reside in dual homes (Collins et al., 2008). Similarly, fathers’ perceptions of maternal gatekeeping, where mothers discredit fathers and portray them in a negative light (Ohalete & Georges, 2010), can influence the receptiveness of their children to paternal sex communication and would benefit from further research.

Emergent Issues

Nonverbal sex communication

Directly related to cultural issues underlying communication about sensitive topics are the non-verbal cues that can be as powerful as the overt information received by adolescents. The few studies that have focused on these dimensions (e.g., affective style and direct vs. indirect communication) report on a vital component in the sexual socialization of adolescents. We recommend that more studies be conducted to further explore how non-verbal communication impacts the process and transmits implicit messages that also shape adolescent attitudes and behaviors. Further, the development of scales that measure implicit or indirect communication cues and negative or positive modeling from parents can advance this overlooked dimension of sex communication.

Beyond heteronormativity and able-bodiedness

While children’s assumed heterosexuality continues to guide most sex communication research, there are initial studies that have begun to examine sex talks between parents and their lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) children. Despite mothers reporting concern about impinging on sons’ development of a normative heterosexual identity (Elliott, 2010a) and fathers placing a premium on making sure their sons are socialized into becoming heterosexual (Solebello & Elliott, 2011), we have identified a growing interest in this subpopulation. In light of the cultural shift in the acceptance of LGBT individuals in the U.S. that has caused LGBT children to come out at earlier ages (Friedman et al., 2008), more research on the sexual socialization needs of this population and how their parents can assist with this process is warranted. Because adolescence is the dynamic stage that usually involves sexual experimentation and risk-taking, the minimal attention to parents’ discussion about transitory or potentially permanent same-sex attraction or behavior during adolescence might be missing significant risk factors that impact all adolescents. With LGBT teens at higher risks for negative sexual health outcomes, there is an urgent need to consider how parental guidance about sex, sex orientation and gender identity can affect this population.

Preliminary reports have begun to investigate the conundrum parents and children with chronic conditions face when navigating adolescence (Ballan, 2012; Holmes & Himle, 2014). Aside from LGBT adolescents, children with cognitive issues such as autism; those with chronic illness such as Type I diabetes or HIV infection; and those with other congenital issues would also benefit from further research about how parents assist in their transition to becoming sexually active adults. Because these adolescents are sexual beings and are influenced by the ecological system, a concerted push to account for these adolescents’ normative sexual development needs will improve not only their sexual health specifically, but also their overall psychosocial well-being.

The redefined American family

The changing American family structure that is now more blended and less nuclear redistributes some of the responsibility for sexuality education to other members in the microsystem. Sex communication studies must be inclusive of non-parental family members who can also be influential purveyors of information. Grandparents, along with aunts and uncles, are in unique positions to augment or even provide primary guidance for adolescents’ sex-related developmental needs. Similarly, due to the shift in U.S. demographics, further studies on how to facilitate intergenerational conversations about sex in minority and immigrant families is crucial to assist minority and second generation immigrant youth to navigate sexual concerns in the U.S. Understanding the tension between minority and majority culture or a country of origin’s sexuality values and expectations versus the reality of U.S. acculturated youths’ lives may result in better assistance when they start going through adolescence and early adulthood.

New media

The media’s facilitative role in sex communication noted in this review is not a surprising finding. While the role of the media in general and the internet in particular has been previously examined, further investigations into adolescent social media use and how parents mediate its impact on adolescent sexual health outcomes deserve further scrutiny. Compounded by a technological divide between tech-savvy children and their technologically-challenged parents that is more prominent in minority families and those coming from a lower socioeconomic background, there is an urgency to assist parents to be updated on the web-based influences their children access. A nascent movement to study the relationship between social media use, adolescent outcomes, and parental supervision over children’s presence online has begun. However, commensurate focus on how parents discuss with their children issues about sexuality in the age of sexting, snapchatting and porous Internet privacy is needed. Furthermore, an investigation of how communication between parents and children occurs through varied technological media is necessary given the numerous advancements in communication technology.

Conclusion

As a proximal process that affects children’s sexual development, sex communication is a function of bioecological factors that are complex and multi-dimensional. It is essential to understand sex communication in the context of myriad, often competing, environmental factors to glean how sexual health discussions between parents and children are supported or undermined. Further, the consonance or disjunction of parental versus environmental messages has to be examined to determine how children decide which to listen to and which to disregard. This review has underscored long-established factors that prevent parents from effectively broaching and sustaining talks about sex with their children and has also identified emerging concerns unique to today’s parenting landscape.

Overall, parental factors salient to sex communication are established long before individuals become parents and are acted upon by influences beyond the home. Child-focused communication factors likewise describe a maturing audience that is far from captive. Revolving around parents and children are ecological factors that contribute to how sex discussions occur. Our findings suggest that future work on sex communication must always be sensitive to these contextual forces. The challenge of 21st century sex communication then is to make clear these factors that affect sex communication as an ongoing dialogue that addresses the sexuality-related concerns of all children, ideally beginning at the pre-sexual stage, through adolescence and early adulthood. More than being focused solely on sharing knowledge with children about matters related to sex, parents can assist them to develop the capacity to recognize salient influences on their attitudes and behavior and how they can best respond to these factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Drs. Sharron Docherty, Michael Relf and Ross McKinney for feedback on earlier version of the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Ms. Adrianne Leonardelli who, at the time of the study, was a health information specialist at the Duke University Medical Library. Mr. Flores would like to acknowledge funding assistance from the Surgeon General C. Everett Koop HIV/AIDS Research Grant and from the National Institute of Health’s Ruth Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31NR015013) and Research on Vulnerable Women, Children, and Families (T32NR007100).

References

Articles reviewed are denoted with an asterisk (*).

- *.Afifi TD, Joseph A, Aldeis D. Why Can’t We Just Talk About It? : An Observational Study of Parents’ and Adolescents’ Conversations About Sex. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(6):689–721. doi: 10.1177/0743558408323841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akers AY, Holland CL, Bost J. Interventions to improve parental communication about sex: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):494–510. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Akers AY, Schwarz EB, Borrero S, Corbie-Smith G. Family discussions about contraception and family planning: a qualitative exploration of black parent and adolescent perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health. 2010;42(3):160–167. doi: 10.1363/4216010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Akers AY, Yonas M, Burke J, Chang JC. “Do you want somebody treating your sister like that?”: qualitative exploration of how African American families discuss and promote healthy teen dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(11):2165–2185. doi: 10.1177/0886260510383028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Alcalde MC, Quelopana AM. Latin American immigrant women and intergenerational sex education. Sex Education. 2013;13(3):291–304. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2012.737775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Aronowitz T, Agbeshie E. Nature of Communication: Voices of 11-14 Year Old African-American Girls and Their Mothers in Regard to Talking About Sex. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2012;35(2):75–89. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2012.678260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Aronowitz T, Todd E, Agbeshie E, Rennells RE. Attitudes that affect the ability of African American preadolescent girls and their mothers to talk openly about sex. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28(1):7–20. doi: 10.1080/01612840600996158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Askelson NM, Campo S, Smith S, Lowe JB, Dennis LK, Andsager J. The Birds, the Bees, and the HPVs: What Drives Mothers’ Intentions to Use the HPV Vaccination as a Chance to Talk About Sex? Journal of Pediatric Healthcare. 2011;25(3):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Askelson NM, Campo S, Smith S. Mother-daughter communication about sex: the influence of authoritative parenting style. Health Communication. 2012;27(5):439–448. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.606526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspy CB, Vesely SK, Oman RF, Rodine S, Marshall L, McLeroy K. Parental communication and youth sexual behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(3):449–466. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Averett P, Benson M, Vaillancourt K. Young women’s struggle for sexual agency: the role of parental messages. Journal of Gender Studies. 2008;17(4):331–344. doi: 10.1080/09589230802420003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Baier MEM, Wampler KS. A qualitative study of Southern Baptist mothers’ and their daughters’ attitudes toward sexuality. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(1):31–54. doi: 10.1177/0743558407310730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ballan M. Parental Perspectives of Communication about Sexuality in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(5):676–684. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1293-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ballard SM, Gross KH. Exploring Parental Perspectives on Parent-Child Sexual Communication. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 2009;4(1):40–57. doi: 10.1080/15546120902733141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Martino S, Kanouse DE, Corona R, Klein DJ, Schuster MA. Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children’s sexual behaviors. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):34–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Boyas J, Stauss K, Murphy-Erby Y. Predictors of Frequency of Sexual Health Communication: Perceptions from Early Adolescent Youth in Rural Arkansas. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2012;29(4):267–284. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0264-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris P. The bioecological model of human development Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Volume 1: Theoretical models of human development. 5th. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown DL, Rosnick CB, Webb-Bradley T, Kirner J. Does daddy know best? Exploring the relationship between paternal sexual communication and safe sex practices among African-American women. Sex Education. 2014;14(3):241–256. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.868800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cederbaum JA. The experience of sexual risk communication in African American families living with HIV. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2012;27(5):555–580. doi: 10.1177/0743558411417864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chung PJ, Borneo H, Kilpatrick SD, Lopez DM, Travis R, Jr, Lui C, Schuster MA. Parent-adolescent communication about sex in Filipino American families: a demonstration of community-based participatory research. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(1):50–55. doi: 10.1367/A04-059R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chung PJ, Travis R, Jr, Kilpatrick SD, Elliott MN, Lui C, Khandwala SB, Schuster MA. Acculturation and parent-adolescent communication about sex in Filipino-American families: a community-based participatory research study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(6):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clawson CL, Reese-Weber M. The amount and timing of parent-adolescent sexual communication as predictors of late adolescent sexual risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(3):256–265. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Coffelt TA. Is sexual communication challenging between mothers and daughters? Journal of Family Communication. 2010;10(2):116–130. doi: 10.1080/15267431003595496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Collins C, Angera J, Latty C. College aged females’ perceptions of their fathers as sexuality educators. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research. 2008;2(2):81–90. [Google Scholar]

- *.Cornelius J, LeGrand S, Jemmott L. African American grandfamilies’ attitudes and feelings about sexual communication: Focus group results. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(2):133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cornelius JB, Cornelius MAD, White AC. Sexual communication needs of African American families in relation to faith-based HIV prevention. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2013;20(3):146–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cornelius JB, LeGrand S, Jemmott L. African American grandparents’ and adolescent grandchildren’s sexuality communication. Journal of Family Nursing. 2008;14(3):333–346. doi: 10.1177/1074840708321336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]