Abstract

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has expanded our understanding of atherosclerotic plaque morphology, and provides an opportunity to guide cardiovascular interventions and evaluate results. Use of this technique requires understanding of ultrasound physics, catheter differences, skills in vessel, plaque and stent quantification and knowledge of artifacts and various physiologic and pathologic findings. Optimal cardiovascular interventions should result in absence of inflow or outflow obstruction, precise geographic landing, while attaining the largest feasible luminal gain without plaque protrusion, vessel dissection or perforation and, if deployed, with complete stent expansion and apposition to the vessel wall. IVUS is safe, cost efficient and effectively optimises cardiovascular interventions. In addition, IVUS improves outcomes when used to guide coronary interventions using bare metal stents (BMS) and drug eluting stents (DES). The role of IVUS in endovascular therapy is rapidly expanding. This review will focus on the impact of IVUS in clinical practice.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Intravascular ultrasonography, percutaneous coronary intervention

Introduction

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has enhanced our understanding of atherosclerotic plaque morphology, and provides a unique opportunity to guide cardiovascular interventions and evaluate the results of these interventions. IVUS is safe, cost efficient and effective in guiding clinical decisions and cardiovascular interventions and improves outcomes when used during coronary artery stenting. Although a comprehensive IVUS overview is beyond the scope of this article, this review will focus on the impact of IVUS in clinical practice.

Intravascular Ultrasound Transducer Types and Common Artifacts

Table 1 describes characteristics of some IVUS catheters. There are two different catheter types – mechanical-state or rotating transducer catheters, and solid-state or electronic array catheters. Most Volcano Corporation (Rancho Cordova, CA) catheters use electronic array technology, where multiple phased-array elements are oriented circumferentially and receive backscattered ultrasound signals which are then processed into real-time images. These catheters do not require rotation for image acquisition. Boston Scientific Corporation (Natick, MA) catheters, and catheters such as the ViewIT, Terumo Corporation (Tokyo, Japan), and HD-IVUS, Acist Medical Systems Inc. (Eden Prairie, MN), use a rotating transducer design where one rotating element captures signals with each revolution. This design requires a catheter housing and a flexible cable to rotate the transducer element. Frequent system flushing is imperative to eliminate air bubbles that may accumulate within the catheter housing creating image artifacts. A wire channel runs adjacent to the Boston Scientific transducers and may also create artifacts. Volcano catheters eliminate the wire artifact by housing the guide wire central to its transducer elements. Non-uniform rotational distortion (NURD) may occur during non-homogeneous transducer rotation seen in electronic array catheters, frequently due to wire bias in the presence of vessel tortuosity. Boston Scientific offers an automatic software correction to minimise NURD. Figure 1 shows various image artifacts.

Table 1: Characteristics of Various Intravascular Ultrasound Catheters.

| Catheter | Ultrasound Frequency (MHz) | Imaging Diameter (mm) | Minimum Guide Catheter Diameter (Fr) | Minimum Sheath Diameter (Fr) | Distal Shaft Diameter (Fr) | Working Length (cm) | Wire (inch) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volcano Eagle Eye Platinum | 20 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 3.3 | 150 | 0.014 | Solid state IVUS. Highly deliverable plug-and-play. GlyDx hydrophilic coating. 3 radiopaque markers 10 mm apart from each other. VH IVUS and ChromaFlo imaging. |

| Volcano Visions PV 0.018 | 20 | 24 | 5 | 6 | 3.4 | 135 | 0.018 | Solid state digital IVUS. Plug and play. ChromaFlo imaging. |

| Volcano Visions PV | 10 | 60 | n/a | 8.5 | 7 | 90 | 0.035 | Solid state digital IVUS. Plug and play. |

| Volcano Revolution | 45 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 3.3 | 135 | 0.014 | Rotational IVUS. Has 150 mm pullback length. |

| Boston Atlantis SR Pro | 40 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 3.2 | 135 | 0.014 | Rotational IVUS. Highly deliverable and excellent image quality. Asahi Intecc drive cable and BioslideTM Coating. 150 mm pullback length. Distance from marker band to transducer is 21 mm. |

| Boston Scientific iCross | 40 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 3.2 | 135 | 0.014 | Rotational IVUS. Bioslide Hydrophilic Coating. Highly deliverable and excellent image quality. |

| Boston Scientific OptiCross™ Catheter | 40 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 3.15 | 135 | 0.014 | Rotational IVUS. Smallest crossing profile. Highest axial resolution (38 micron). 150 mm pullback. |

| Boston Scientific Atlantis 0.018 Peripheral Imaging Catheter | 40 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 3.2 | 135 | 0.018 | Rotational IVUS. Highly deliverable and excellent image quality. |

| Boston Scientific Atlantis PV Peripheral Imaging Catheter | 15 | 30 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 95 | 0.035 | Rotational IVUS. |

| Boston Scientific Atlantis ICE 9 mHz | 9 | 50 | n/a | 9 | 9 | 110 | n/a | Rotational IVUS. |

Boston Scientific Corporation (Natick, MA). Volcano Corporation (Rancho Cordova, CA). IVUS = Intravascular ultrasound; MHz = Mega Hertz; Fr = French; ICE= Intracardiac echocardiography.

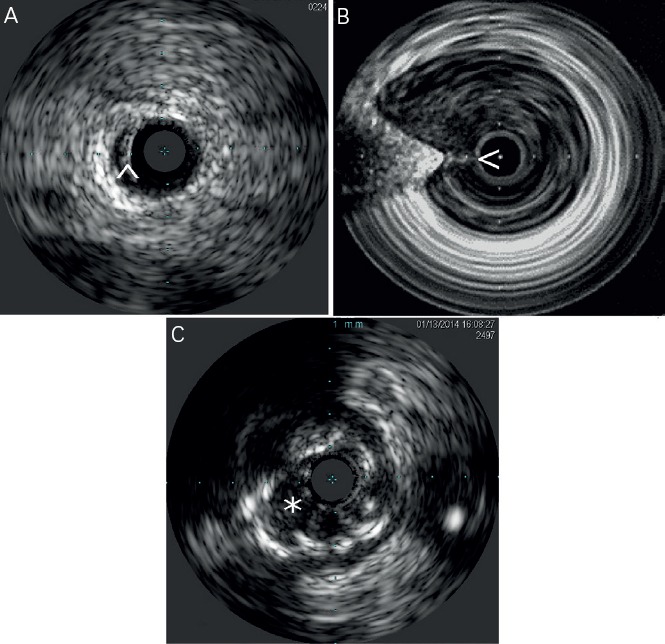

Figure 1: Common Artifacts Present During Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging.

A) Arrowhead points at a ringdown artifact. B) Image shows non uniform rotational distortion artifact. Additionally a wire artifact is signaled by the arrowhead. C) Asterisk points at blood speckle artifacts that can make it difficult to visualize intraluminal structures. This artifact can be cleared with a saline flush.

Available IVUS catheters used for most coronary, renal, iliac and infra-inguinal arterial assessment are compatible with 5–6 French sheaths. Low frequency catheters offer an expanded imaging field at the expense of proximal image resolution and are utilised for aortic and venous imaging. High-frequency catheters offer improved image resolution but have a narrower field of imaging. The axial resolution varies among common imaging catheters: Eagle Eye® – <170 microns; Revolution™ – 50 microns; iCross™ – 43 microns and OptiCross™ – 38 microns.

Near-field artifacts include ringdown and blood speckle artifacts, with the latter one clearing during saline flushing. With phased array catheters, interference can occur around the catheter creating a resonance phenomenon that leads to a long and uninterrupted echo producing a blind area or ringdown artifact.

Side lobe artifacts are caused by multiple low-energy sound beams that arise from the main ultrasound beam. The receiver detects and erroneously assigns these low energy beams to the main beam parallel to the false location. They are commonly bright rounded lines displayed over hypoechoic or anechoic structures adjacent to hyperechoic structures.

Vessel measurements are ideally performed with the transducer perpendicular to the vessel wall. Position artifacts caused by catheter obliquity, and vessel curvature or eccentricity may especially be of clinical significance in larger vessels. Catheter motion artifact may result from forward transducer translation during vessel flushing. Axial translation may also be observed during cardiac or breathing cycle variation.

Anatomical Assessment and Intervention Guidance

Various studies have demonstrated advantages of IVUS guided interventions when compared to angiography.[1–12] An analysis of the Strategy and intracoronary ultrasound-guided PTCA and stenting (SIPS) trial[4] noted a 60.9 % probability that IVUS was less expensive and more effective when compared to angiographic guided interventions. Similarly, Gaster et al. demonstrated decreased cost with an IVUS guided intervention strategy.[5] Intravascular ultrasound confers improved accuracy for lesion quantification (e.g. lumen, vessel wall and plaque diameter, area, length, shape and volume), and morphology assessment (e.g. aneurysms, bifurcations, ostial lesions, fibrosis and calcification patterns, filling defects, thrombus, intimal disruption, dissection and ulceration). Additionally IVUS shows the calcium distribution pattern within the vessel wall.[13] IVUS is also more accurate than angiography for assessment of eccentric lesions.[14] IVUS can aid in the identification of the culprit lesion in unclear cases and clarify the mechanism of Stent thrombosis (ST) or in-stent restenosis (ISR).[15,16] Distal embolisation or peri-procedural myocardial infarction (MI) during interventions may be predicted with the IVUS presence of ruptured plaque and large plaque burden in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and non-ACS patients.[17] Greater attenuation angle (>180 degrees), and attenuation length >5 mm seem to be independent predictors for microvascular obstruction in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing primary PCI.[18] Pre-emptive use of filter wires in these patient subgroups may prove beneficial. Table 2 and Figure 2 show common IVUS measurements and morphologic findings.

Table 2: Basic Intravascular Ultrasound Measurements.

| Basic Measurements |

|---|

| External Elastic Membrane (EEM) CSA: Total vessel CSA or ‘medial’ area. It is the boundary between the echo lucent media and bright adventitia. |

| Lumen or stent CSA |

| Maximum and minimum lumen or stent diameter: Luminal measurement through the center of the lumen or stent. |

| Plaque and media (P + M) CSA (Atheroma CSA) |

| a- EEM CSA – Lumen CSA (no stent) |

| b- EEM CSA – Stent CSA (stented lesions) |

| Intimal hyperplasia CSA: Stent CSA – lumen CSA |

| Eccentricity: Maximal / mininimal P+M thickness |

| Plaque burden (% atheroma area) |

| a- Atheroma CSA / EEM CSA |

| Remodeling index: Lesion EEM CSA / predefined reference EEM |

| Area stenosis: Lesion lumen CSA / predefined reference lumen CSA |

| Arc of calcium: degrees of circumference covered by calcium |

| Lesion length: Measured using motorized transducer pullback at a fixed speed |

CSA: Cross sectional area; EEM: External elastic membrane.

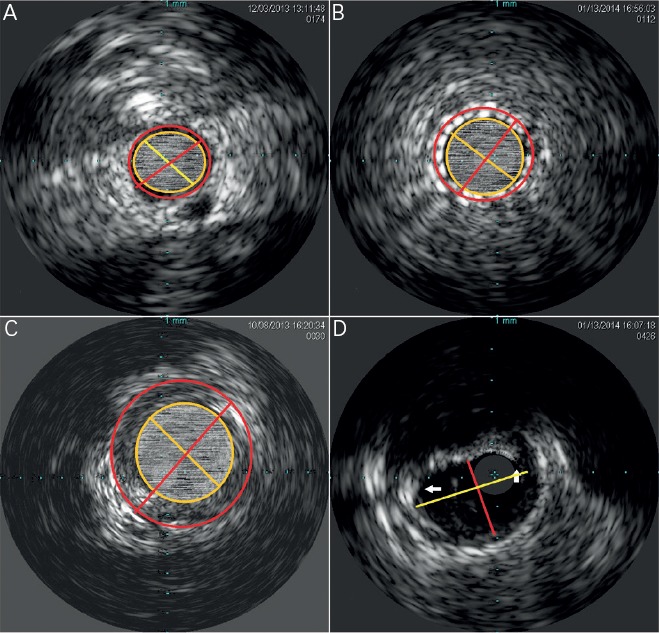

Figure 2: Basic Intravascular Ultrasound Measurements.

A) The lumen CSA is the area contained within the yellow inner circle. The EEM CSA is contained by the outer red circle. The yellow line represents the lumen diameter, and the red line represents the total vessel diameter. B) The stent CSA is the area contained within the yellow inner circle. The EEM CSA is contained by the outer red circle. The yellow line represents the stent lumen diameter, and the red line represents the total vessel diameter. C) After excluding the lumen CSA from the EEM CSA the residual area represents the atheroma CSA (Plaque and media CSA. D) The maximum luminal diameter is represented by the longer yellow line, and the minimum lumen diameter is represented by the shorter red line. The white arrows point to the borders of the near 155 degree arc of fibro-calcific plaque. CSA = cross sectional area; EEM = External elastic membrane.

Mechanised pullback at a stable speed allows for length calculation[19] but limits dynamic interactions by the operator that are available during manual pull-back. Knowledge of the distance between IVUS catheter markers may alternatively be used to estimate length when combined with fluoroscopy (see Figures 3 and 4). Eagle Eye® Platinum Rx Digital IVUS Catheters, (Volcano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA) have 14 mm from transducer to its first radiopaque marker, and a total of three markers each 10 mm apart. A short tip version of the catheter is available (Eagle Eye® Platinum ST Rx Digital IVUS Catheters, Volcano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). Atlantis® SR Pro Coronary Imaging Catheter (Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA) has a 2.1 cm distance from marker band to its transducer. The OptiCross™ Coronary Imaging Catheter, (Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA) has a 1 cm telescope marker that allows to calculate the manual pullback distance.

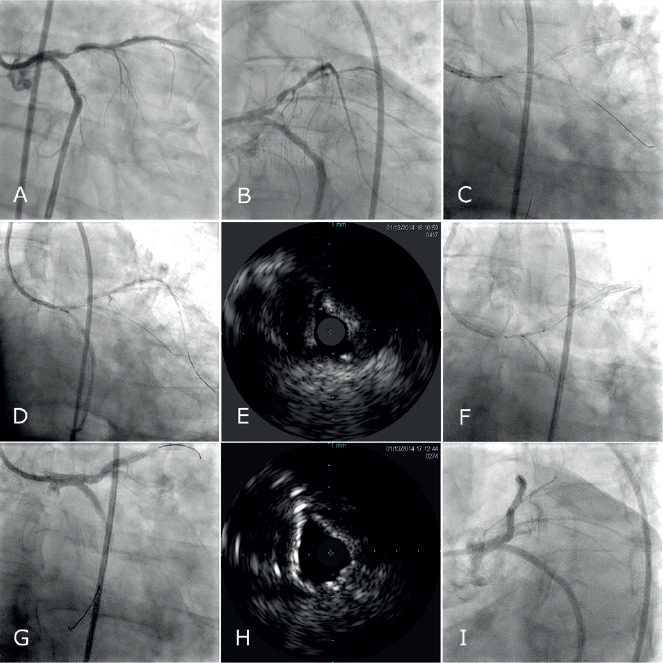

Figure 3: Serial Cine and IVUS Images Demonstrate the Use of Intravascular Ultrasound to Mark Structures of Interest During Coronary Interventions.

A–B) Angiographic views show ostial LAD and LCx stenoses. C–D) The imaging window is positioned at the ostium of the C) LAD and then the D) LCx and short cine runs are obtained to mark their respective locations, using an Eagle Eye® Platinum ST Rx Digital IVUS Catheter, (Volvano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). E) An IVUS image of the LCx ostium prior to intervention is shown. F) A two stent strategy is chosen and stents are positioned in accordance to the IVUS guided ostial marking. G) Post intervention G, I) cine and H) IVUS findings are shown. LAD: Left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx: Left circumflex coronary artery; IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound.

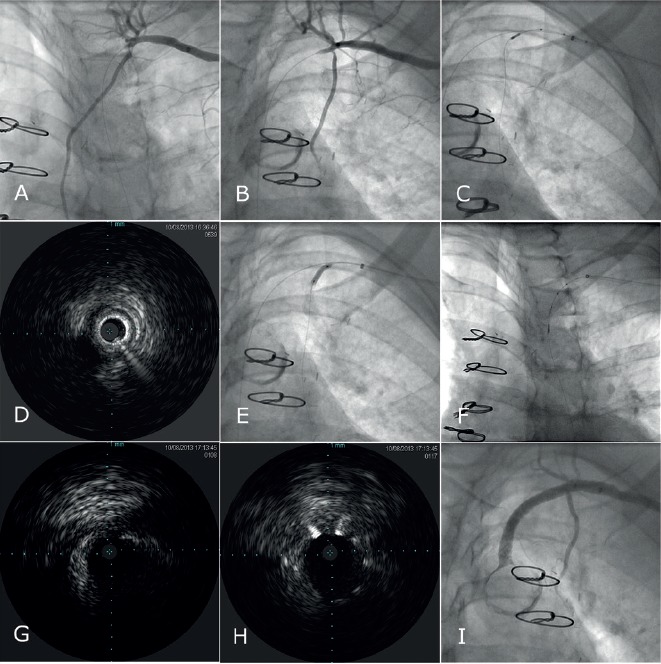

Figure 4: Serial Cine and IVUS Images Demonstrate the Use of Intravascular Ultrasound to Mark Structures of Interest During Peripheral Interventions.

A–B) Angiographic views show a left SCA chronic total occlusion crossed by a guidewire and an ostial LIMA stenosis in a patient with angina pectoris and a prior LIMA bypass. The imaging window is positioned at the ostium of the LIMA and C) a short cine run is obtained to mark the LIMA ostium location using an Eagle Eye® Platinum ST Rx Digital IVUS Catheter, (Volvano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). D) IVUS image of the LIMA ostium is shown. E) The LIMA ostium undergoes stent deployment. F) The SCA ostium is marked and the vessel distance is calculated using the 10 mm distance between the markers of the Eagle Eye® Platinum ST Rx Digital IVUS Catheter. IVUS images of the SCA ostium are observed G) pre intervention, and H) post intervention, confirming accurate geographic stent landing. I) Final cine findings are shown. SCA: Subclavian artery; LIMA: Left internal mammary artery; IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound.

Vessel areas of interest, (e.g. bifurcations, ostium, beginning and end of diseased vessels) can be accurately localised using the transducer marker adjacent to the imaging window. This is done by positioning the transducer at the area of interest followed by cine acquisition of the transducer marker. This marker position is compared to other adjacent fluoroscopic landmarks for future orientation. This technique allows for optimal geographic landing of interventional equipment. Gentle flushing is advised when injecting contrast during imaging for marker position evaluation, as brisk flushing may result in forward transducer translation producing a catheter motion artifact. Similarly, careful attention to catheter position is important to detect motion during cardiac or breathing cycle variation. IVUS guided PCI of native aorto-ostial, or ostial left anterior descending, left circumflex, or ramus intermedius lesions has been associated with lower rates of the composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) or target lesion revascularisation (TLR) (hazard ratio [HR] 0.54, 95 % CI 0.29-0.99; p = 0.04), composite MI or TLR (HR 0.39, 95 % CI 0.18-0.83; p = 0.01) and MI (HR 0.31, 95 % CI 0.11–0.85; p = 0.02), as well as a trend towards a lower TLR rate (HR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.17-1.02; p = 0.06) compared with no IVUS.[20]

Although not available in the US, Boston Scientific offers iMap tissue characterisation software which uses radiofrequency signal spectrum pattern recognition to characterise tissue within the plaque.[21] Boston Scientific also offers volumetric analysis software. Volcano offers virtual histology software (VH® IVUS) that identifies signal intensity and frequency variations and assigns different colours to each specified category with the goal of tissue composition characterisation, fibrous, fibro-fatty, necrotic-lipid and calcific, (see Figure 5).[22] Volcano also offers ChromaFlo®; a colour flow function that highlights changes between serial frames and may assist in the identification of intraluminal filling defects (e.g. thrombus, unopposed stent struts, vessel dissection). Superficial echo attenuated plaques have been associated with advanced necrotic core containing fibroatheromas which are considered a high risk plaque pattern.[23] However, secondary non-culprit ruptures frequently seen in ACS patients with this plaque phenotype do not seem to be associated with adverse outcomes on patients treated with optimal medical therapy.[24] The clinical application of non-culprit plaque characterisation is therefore unclear at this time.

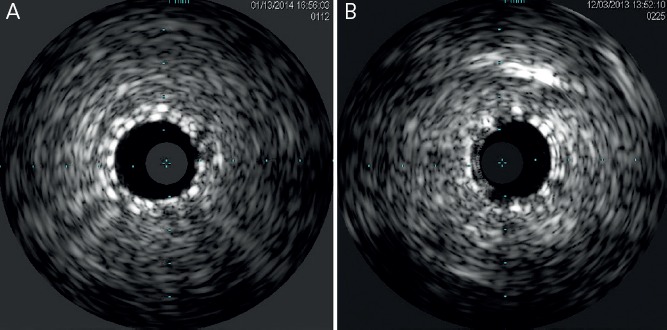

Figure 5: IVUS Images Demonstrating A) Normal and B–F) Diseased Vessel Segments.

IVUS images demonstrating A) normal and B–F) diseased vessel segments. B) A fibro-calcific plaque is shown expanding between 9 and 11 o’clock. C, E) Bulky soft plaque (fibro-fatty) and D, F) necrotic-fatty plaque examples are shown. Images E and F show virtual histology IVUS (Volvano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound.

IVUS may clarify difficult scenarios that are uncertain by angiography, (e.g. left main coronary artery (LMCA disease), significance of inflow or outflow disease, bifurcation classification including evaluation for side branch disease), and aid in the selection of an optimal technical approach to interventions. Determining morphological characteristics associated with decreased vessel compliance, (e.g. extended arc of calcium or significant fibrosis) may assist the decision to use pre-emptive atherectomy.[25]

IVUS for BMS and DES Implantation

Pre-intervention vessel size, lesion length and morphology are evaluated to select the appropriate strategy and stent size and length. Post-intervention stent landing, expansion and apposition are evaluated. Complications are excluded (e.g. malapposed or under-expanded stents, geographic miss, dissections, plaque prolapse, residual thrombus), and fine tuning performed. Figure 6 demonstrates some post intervention issues encountered during IVUS.

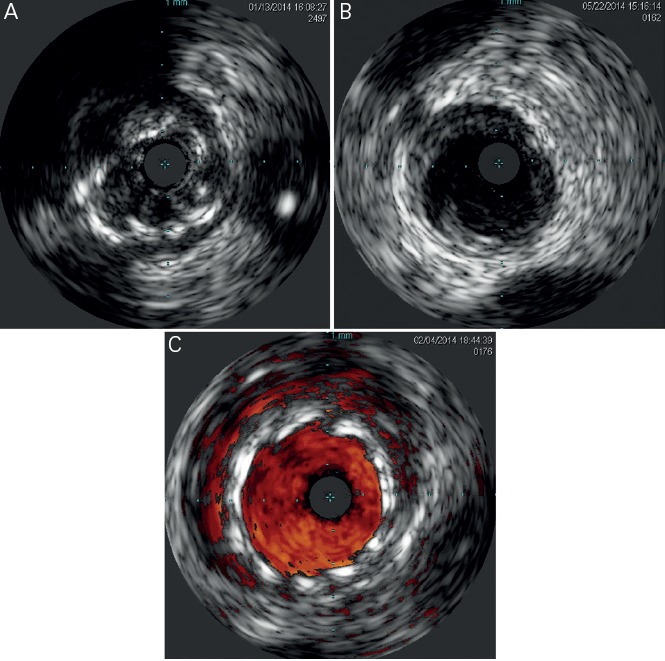

Figure 6: IVUS Images Demonstrate Common Pathologic Findings Following Cardiovascular Interventions.

A) Stent under-expansion. B) Edge dissection is observed following coronary angioplasty. C) Stent mal-apposition is highlighted using Chroma-Flow (Volvano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA). IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound.

Fluoroscopy may miss stent under-expansion, a predictor of stent thrombosis (ST) after bare metal stent (BMS) implantation.[15] Fujii et al.[16] identified stent under-expansion and residual reference segment stenosis as predictors of ST after sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) implantation. In addition to stent under-expansion, a higher residual disease burden at the stent edges has been associated with stent thrombosis.[26] This may explain the higher rate of mIss noted by Costa et al.[27] in a cohort of patients with geographic miss following SES implantation.

Higher BMS ISR rates are observed with smaller minimal stent area (MSA) and longer stent length.[28] A stent minimal luminal area (MLA) < 6 mm2 was observed in 28 % of BMS ISR cases. Similarly 4.5 % of these ISR cases had unrecognised mechanical complications (geographic miss, stent deformation and balloon stripping during the implantation procedure) readily detectable by IVUS.[29] Everolimus eluting stents (EES) associated mechanical complications, (e.g. partial or complete stent fracture, strut fracture with overlapping stent fragments, and longitudinal deformation) have been associated with excessive neo-intimal hyperplasia, ISR and repeat revascularisation.[30] Sonoda et al.[31] observed a correlation between BMS and SES MSA and long term development of ISR. Fujii et al.[32] found stent under expansion (MSA < 5.0 mm2) to be associated with ISR after SES implantation. Similarly, Hong et al.[33] corroborated MSA < 5.5 mm2 as an independent predictor of angiographic restenosis after SES implantation and also found a stent length > 40 mm2 to predict restenosis. A meta-analysis[34] evaluating BMS and Taxus paclitaxel eluting stent (PES), observed that IVUS maximum percentage of intimal hyperplasia correlated with restenosis at nine months.

Sakurai et al.[35] found that residual reference vessel plaque burden and stent over-sizing relative to the reference vessel were associated with edge stenosis in a SES when compared to a BMS cohort. Liu et al.[36] found residual edge plaque burden and not edge lumen area to be predictive of nine month stent edge restenosis after BMS or TAXUS PES implantation. Costa et al.[27] found a high rate (66.5 %) of longitudinal and axial geographic miss following SES implantation. At one year follow-up TVR rates in the geographic miss group was 5.1 % compared to 2.5 % in the non-geographic miss group (p=0.025). There was a 3-fold increase in MI rates associated with geographic miss (2.4 % vs 0.8 %; p=0.04). The long-term health outcome and mortality evaluation after invasive coronary treatment using drug-eluting stents with or without the IVUS guidance study[11] failed to demonstrate superiority of IVUS use to guide DES implantation using standard high pressure post-dilatation. However, the Angiography vs IVUS Optimisation (AVIO) study[12] showed benefit in the post-procedure minimal lumen diameter (2.70 mm +/- 0.46 mm vs 2.51 +/- 0.46 mm; P = .0002), when using IVUS compared to angiography to optimise implantation. At 24-months follow-up no differences were observed for cumulative MACE, cardiac death, MI, target lesion revascularisation or target vessel revascularisation. The Assessment of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES),[37] a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised study of 8,583 consecutive patients, showed that IVUS guidance was associated with a reduction in stent thrombosis (0.6 % vs 1.0 %; HR 0.40; 95 % CI 0.21–0.73; P=0.003), MI (2.5 % vs. 3.7 % HR 0.66; 95 % CI 0.49–0.88; P=0.004), and major adverse cardiac events (cardiac death, MI, or stent thrombosis), (3.1 % vs 4.7 %; HR 0.70; 95 % CI 0.55-0.88; P=0.002) within one year after DES implantation. Larger stents, longer stents and/or higher inflation pressures were used in 74 % of IVUS guided cases. A pooled analysis of four registries included 1,670 patients with LM disease undergoing DES implantation. Thirty percent of the group underwent IVUS guided DES implantation and were compared against the non- IVUS group using a propensity score-matching method. Survival free of cardiac death, MI and TLR at three years was significantly lower in the IVUS guided group (88.7 % vs 83.6 %, p: 0.04). Similarly thrombosis was lower in the IVUS guided group (0.6 % vs. 2.2 %, p = 0.04).[38] Two recent meta-analyses favour the use of an IVUS guided strategy as opposed to an angiography guided strategy for DES implantation. One meta-analysis included 26,503 patients from three randomised and 14 observational studies. IVUS-guided PCI was associated with larger, longer and more stents, and lower risk of death (OR 0.61, 95 % CI 0.48 to 0.79, p<0.001), MI (OR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.44 to 0.75, p<0.001), TLR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.66 to 1.00, p=0.046), and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.47 to 0.75, p<0.001) after drug-eluting stent implantation.[39] These results were consistent with a meta-analysis by Jang et al.[40] which encompassed 11,793 IVUS guided and 13,056 angiography guided patients from three randomised trials and 12 observational studies. In this study, the IVUS guided strategy was associated with lower rates of MACE (OR 0.79, 95 % CI 0.69 – 0.91, p: 0.001), all - cause mortality (OR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.51 – 0.81, p: 0.001), MI (OR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.42 – 0.78, p: < 0.001), TVR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.68–0.95, p: 0.01) and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.42–0.82, p = 0.002).

The achievement of optimal stent size cannot be predicted using the manufacturer’s compliance charts when using BMS or DES. The average achieved minimal stent diameter (MSD) is 75 % of the predicted MSD and 66 % of the predicted MSA when compared to IVUS measurements.[41] Adequate vessel sizing is especially important when using bioresorbable vascular scaffolds.[42] Scaffolds require quantitative coronary angiography or IVUS guided measurement for optimal results. An IVUS example of scaffolds as compared to stent struts is shown on Figure 7.

Figure 7: IVUS Images Showing; A) Apposed Stent Struts, B) Apposed Absorb Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Illinois).

IVUS: Intravascular Ultrasound.

IVUS for Chronic Total Occlusion (CTO) Intervention Guidance

IVUS for CTO interventions can assist in lowering contrast use, and improve the procedure safety. IVUS-guided controlled antegrade and retrograde subintimal tracking (CART or reverse CART) techniques are final CTO revascularisation steps that can be performed safely and effectively with IVUS guidance.[43] Alternatively, transvenous IVUS-guided PCI for CTO has been described using the cardiac vein parallel to the target artery.[44] The recently acquired Volcano Corporation Pioneer Plus™ Re-Entry Catheter, (Volcano Corporation, Rancho Cordova, CA) is a peripheral reentry device that uses an adjustable access needle coupled to an IVUS for real-time visualisation during CTO vessel re-entry into the distal luminal space.

IVUS Validation for Ischaemia Assessment

Resistance to flow by a stenosis depends on various factors such as entrance effects, friction loss and separation loss. Vessel resistance is inversely related to the stenosis area, and directly proportional to viscosity and stenosis length. Separation loss is magnified by turbulence created by increased flow across a stenosis, and inversely related to the stenosis area and reference area of the vessel downstream to the stenosis. Additionally, the complex interaction between the vascular bed integrity, varying degrees of diffuse disease, vessel remodelling and a branching coronary tree with serial and parallel stenoses leads to complex haemodynamics that confound the use of stenosis area as an optimal single marker for stenosis significance. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) takes many of these factors into account and is the preferred invasive tool to answer what is the physiological significance of coronary stenosis. A caveat with the use of FFR that is most pronounced for left main stenosis assessment is the need to take into account the potential effect of concomitant lesions in either of its branches. A downstream flow limiting lesion will minimise the FFR significance of the left main stenosis as a result of decreased flow crossing the left main. The ultimate clinical decision lies in the conscious operator’s ability to combine various data points to obtain a final answer.

Abizaid et al.[45] reported a diagnostic accuracy of 92 % using an IVUS minimal lumen area (MLA) < 4.0 mm2 compared to a Doppler flow wire coronary flow reserve (CFR) of < 2.0. However, this cutoff misclassified 8.3 % of patients as either false negative or false positive (two patients with MLA > 4.0 had CFR < 2.0. and four patients with MLA 4.0 or less had a CFA of 2.0 or above. NPV: 0.95 and PPV: 0.93). Similarly Nishioka et al.[46] reported a diagnostic accuracy of 93 % for detecting an abnormal Thallium SPECT perfusion study using the 4.0 MLA cutoff. This study misclassified 7 % of patients (four patients with MLA > 4.0 had an abnormal SPECT study and one had an MLA of 4.0 or less and a negative perfusion study. NPV = 0.83 and PPV = 0.91. Takagi et al.[47] found that most MLA values <4.0 mm2 were associated with an FFR <0.75, however, several patients with an MLA <4 mm2 still had FFR values above 0.8. In this study, regression analysis identified MLA <3.0 mm2 and area stenosis > 60 % as optimal IVUS thresholds (sensitivity 83 % and 92 %; specificity 92.3 % and 88.5 % respectively for MLA and area stenosis). In this study the combination of both criteria (MLA <3.0 mm2 and area stenosis >60 %) met an FFR <0.75 without exception. Similarly, Briguori et al.[48] reported the combination of percent area stenosis and minimum lumen diameter (MLD) increased the IVUS specificity. IVUS cutoffs of area stenosis >70 %, MLD of 1.8 mm or less, MLA of 4.0 mm2 or less, and lesion length > 10 mm reliably identified lesions with an FFR < 0.75 in this study. As can be observed in these studies, although a MLA <4.0 mm2 in proximal coronary vessels other than the left main or saphenous vein grafts has been frequently associated with the presence of a physiologically significant stenosis, not every MLA <4 mm2 equates to an ischaemia inducing stenosis.

Abizaid et al.[49] evaluated 357 non-left main intermediate stenosis in whom intervention was deferred based on IVUS findings. At one year, the event rate of 248 lesions with a MLA of 4.0 mm2 or more was 4.4 % and TLR rate 2.8 %. No events were noted when the MLA was >6.2 mm2. However, the Physiologic and anatomical evaluation prior to and after stent implantation in small coronary vessels (PHANTOM) trial found a lack of correlation between angiography or IVUS, and FFR in patients with moderate stenosis in small coronary arteries (<2.8 mm).[50] An MLA of 2.4 mm2 or above correlated with an FFR of 0.8 or higher, however the poor specificity was noted as a significant limitation by Kang et al.[51] Similarly, Ahn et al.[52] found a lower MLA cutoff of 2.1 mm2 to correlate with myocardial ischaemia by myocardial SPECT. This cutoff was also associated with a poor specificity (50.4 %), and a poor positive predictive value (38.6 %).

Angiographic left main coronary artery stenosis assessment suffers from wide inter-operator variability.[53–55] Jasti et al.[56] identified an MLD of 2.8 mm and an MLA of 5.9 mm2 as the most accurate cutoffs for determining the significance of a left main stenosis. (Respectively for MLD and MLA, sensitivity 93 % and 93 %; and specificity 98 % and 95 %). Abizaid et al.[57] reported an adverse event rate of 14 % in patients who underwent angiographic and IVUS assessment of left main disease and were not referred for intervention. When stratified by IVUS MLD, the event rate was 60 % for an MLD < 2.0 mm, 24 % for an MLD 2.0 to 2.5, 16 % for an MLD 2.5 to 3.0 mm and 3 % for an MLD >3.0 mm. For any given MLD, the event rate was exaggerated in the presence of diabetes mellitus or an untreated lesion in a major vessel with >50 % diameter stenosis. Fassa et al.[58] reported the mean 3.3 year follow-up results after deferral of 71 patients with LM stenosis and an MLA >7.5 mm2 and observed no significant difference in target vessel revascularisation, acute MI and death between these patients compared to a group with an MLA <7.5 mm2 who underwent revascularisation (p = 0.28). A multicentre study[59] reported comparable (p = 0.3) two year event free survival rates between a group of patients with left main disease and MLA >6 mm2 that deferred intervention (87.3 % ) compared to that of patients with an MLA of 6 mm2 or less who underwent revascularisation (80.6 %). Only 4.4 % of patients in the deferred group required subsequent LMCA revascularisation, none with an infarction. Patients with a LMCA MLA <6 mm2 who did not undergo revascularisation because of operator or patient preferences had an MLA of 5–6 mm2, and 88 % of these had preserved ejection fraction. Frequently these lesions were complex, the estimated surgical risk was high, and patients had issues with dual antiplatelet therapy use or declined surgery. The two year cardiac death-free survival was 86 % (compared to 97.7 % in the deferred group; p = 0.04), and survival free of cardiac death, MI, and revascularisation was 62.5 % (compared to 87.3 % in the deferred group; p = 0.02).

IVUS and Endovascular Interventions

Literature regarding use of IVUS for endovascular interventions is scarce. Wada et al.[60] reported a small case series of patients undergoing IVUS guided stent placement for subclavian artery disease. Short term results were good and long term outcomes were remarkable for absence of ISR over a 51 month median follow up. Contrast minimising strategies like the use of carbon dioxide digital subtraction and IVUS to guide interventions have been described for renal artery interventions,[61] and for iliac artery CTO interventions.[62]

In addition to providing measurements and precisely locate key landmarks and venous branches, IVUS can identify important abnormalities (e.g. external compression, acute and chronic thrombus, fibrosis, mural wall thickening, spurs and trabeculations) that aid in the adequate execution of strategies to treat venous obstruction and bedside placement of vena cava filters.[63] IVUS-guided bedside placement of inferior vena cava (IVC) filters using a single puncture technique eliminates the risk of transportation, is safe, efficient and cost effective. It may be used in conjunction with pre-procedure computed tomography (CT) derived measurements to minimise filter malposition.[64] IVUS has been used for direct and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement, transcaval liver biopsy, transcaval puncture of type II endoleaks and for cardiac mass biopsies.[65]

Safety and Complications

Strategies to prevent contrast induced nephropathy include adequate hydration and use of IVUS to guide interventions.[61] IVUS has the potential to reduce radiation dose and increase procedure safety as previously discussed. As with any vessel instrumentation, IVUS carries the risk of vessel dissection, injury, perforation or total occlusion, air embolism, unstable angina, MI, haemodynamic instability, arrhythmias, limb ischaemia and death. Studies evaluating coronary IVUS have shown major complication rates ranging from 0.1 % including dissection, thrombus and ventricular arrhythmias[66] to 1.1 % if spasm and guidewire entrapment are accounted for.[67] Spasm has been described as frequently as in 2.9 % of cases,[66] but is rarely refractory to vasodilators and device retrieval.

Future Directions

Similar to Volcano’s automatised lesion assessment software (Target Assist), Boston Scientific is working on advanced lesion assessment software that will allow for automatised bookmarks and measurements for the healthier proximal and distal portions as well as the tightest portion of a lesion immediately following pullback. Hybrid IVUS and optical coherence tomography (OCT) catheters are on the horizon.[68] Co-registration of 3D coronary angiography and IVUS or OCT will improve our understanding of complex lesions and improve our ability to deliver optimal interventional results.[69] Sync Vision™ (Volcano Corporation) will use a built-in device motion indicator and combine anatomical and functional assessment using IVUS and instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio (iFR) co-registration. New transducer technology will offer advancements like increased image resolution, multi-frequency devices, real-time volumetric ultrasound imaging capability,[70] and software improvements to facilitate image interpretation and increase ease of use. IVUS on guide-wires and forward-looking IVUS for use in CTOs are attractive options that may soon complement our current interventional armamentarium.

Conclusions

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has brought us one step closer to the understanding of atherosclerosis, and to achieving safer and more effective interventions. IVUS improves hard outcomes during coronary stenting. This outstanding technology can help us answer clinical questions that are at times otherwise uncertain and has proven to be an invaluable tool for cardiovascular operators. Continued technological IVUS improvements and the combination with other technologies will continue to bring additional excitement to this already amazing field of medicine.

References

- 1.Choi JW, Goodreau LM, Davidson CJ. Resource utilization and clinical outcomes of coronary stenting: a comparison of intravascular ultrasound and angiographical guided stent implantation. Am Heart J. 2001;142:112–8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald PJ, Oshima A, Hayase M et al. Final results of the Can Routine Ultrasound Influence Stent Expansion (CRUISE) study. Circulation. 2000;102:523–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frey AW, Hodgson JM, Muller C et al. Ultrasound-guided strategy for provisional stenting with focal balloon combination catheter: results from the randomized Strategy for Intracoronary Ultrasound-guided PTCA and Stenting (SIPS) trial. Circulation. 2000;102:2497–502. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.20.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller C, Hodgson JM, Schindler C et al. Cost-effectiveness of intracoronary ultrasound for percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaster AL, Slothuus U, Larsen J et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intravascular ultrasound guided percutaneous coronary intervention versus conventional percutaneous coronary intervention. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2001;35:80–5. doi: 10.1080/140174301750164673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaster AL, Slothuus Skjoldborg U, Larsen J et al. Continued improvement of clinical outcome and cost effectiveness following intravascular ultrasound guided PCI: insights from a prospective, randomised study. Heart. 2003;89:1043–9. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.9.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiele F, Meneveau N, Vuillemenot A et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in stent deployment on 6-month restenosis rate: a multicenter, randomized study comparing two strategies--with and without intravascular ultrasound guidance. RESIST Study Group. REStenosis after Ivus guided STenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:320–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oemrawsingh PV, Mintz GS, Schalij MJ et al. Intravascular ultrasound guidance improves angiographic and clinical outcome of stent implantation for long coronary artery stenoses: final results of a randomized comparison with angiographic guidance (TULIP Study). Circulation. 2003;107:62–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043240.87526.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiele F, Meneveau N, Gilard M et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided balloon angioplasty compared with stent: immediate and 6-month results of the multicenter, randomized Balloon Equivalent to Stent Study (BEST). Circulation. 2003;107:545–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047212.94399.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mudra H, di Mario C, de Jaegere P et al. Randomized comparison of coronary stent implantation under ultrasound or angiographic guidance to reduce stent restenosis (OPTICUS Study). Circulation. 2001;104:1343–9. doi: 10.1161/hc3701.096064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jakabcin J, Spacek R, Bystron M et al. Long-term health outcome and mortality evaluation after invasive coronary treatment using drug eluting stents with or without the IVUS guidance. Randomized control trial. HOME DES IVUS. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;75:578–83. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chieffo A, Latib A, Caussin C et al. A prospective, randomized trial of intravascular-ultrasound guided compared to angiography guided stent implantation in complex coronary lesions: the AVIO trial. Am Heart J. 2012;165:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD et al. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995;91:1959–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD et al. Limitations of angiography in the assessment of plaque distribution in coronary artery disease: a systematic study of target lesion eccentricity in 1446 lesions. Circulation. 1996;93:924–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheneau E, Leborgne L, Mintz GS et al. Predictors of subacute stent thrombosis: results of a systematic intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2003;108:43–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078636.71728.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii K, Carlier SG, Mintz GS et al. Stent underexpansion and residual reference segment stenosis are related to stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:995–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo K, Ueda Y, Tsujimoto M et al. Ruptured plaque and large plaque burden are risks of distal embolisation during percutaneous coronary intervention: evaluation by angioscopy and virtual histology intravascular ultrasound imaging. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:235–42. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I2A39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiono Y, Kubo T, Tanaka A et al. Impact of attenuated plaque as detected by intravascular ultrasound on the occurrence of microvascular obstruction after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:847–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka K, Carlier SG, Mintz GS et al. The accuracy of length measurements using different intravascular ultrasound motorized transducer pullback systems. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2007;23:733–8. doi: 10.1007/s10554-007-9216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel Y, Depta JP, Patel JS Impact of intravascular ultrasound on the long-term clinical outcomes in the treatment of coronary ostial lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. Jun 1, 2013. [ePub ahead of Print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sathyanarayana S, Carlier S, Li W, Thomas L. Characterisation of atherosclerotic plaque by spectral similarity of radiofrequency intravascular ultrasound signals. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:133–9. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i1a21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair A, Kuban BD, Tuzcu EM et al. Coronary plaque classification with intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis. Circulation. 2002;106:2200–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000035654.18341.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pu J, Mintz GS, Biro S et al. Insights into echo-attenuated plaques, echolucent plaques, and plaques with spotty calcification: novel findings from comparisons among intravascular ultrasound, near-infrared spectroscopy, and pathological histology in 2,294 human coronary artery segments. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2220–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Mintz GS, Yang J et al. Clinical outcome of nonculprit plaque ruptures in patients with acute coronary syndrome in the PROSPECT study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Saijo Y, Majdouline Y et al. Coronary artery atherectomy reduces plaque shear strains: an endovascular elastography imaging study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okabe T, Mintz GS, Buch AN et al. Intravascular ultrasound parameters associated with stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent deployment. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa MA, Angiolillo DJ, Tannenbaum M et al. Impact of stent deployment procedural factors on long-term effectiveness and safety of sirolimus-eluting stents (final results of the multicenter prospective STLLR trial). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1704–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Feyter PJ, Kay P, Disco C, Serruys PW. Reference chart derived from post-stent-implantation intravascular ultrasound predictors of 6-month expected restenosis on quantitative coronary angiography. Circulation. 1999;100:1777–83. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.17.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castagna MT, Mintz GS, Leiboff BO et al. The contribution of “mechanical” problems to in-stent restenosis: An intravascular ultrasonographic analysis of 1090 consecutive in-stent restenosis lesions. Am Heart J. 2001;142:970–4. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inaba S, Mintz GS, Yun KH et al. Mechanical complications of everolimus-eluting stents associated with adverse events: an intravascular ultrasound study. EuroIntervention. 2014;9:1301–8. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I11A220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonoda S, Morino Y, Ako J et al. Impact of final stent dimensions on long-term results following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: serial intravascular ultrasound analysis from the sirius trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujii K, Mintz GS, Kobayashi Y et al. Contribution of stent underexpansion to recurrence after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for in-stent restenosis. Circulation. 2004;109:1085–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121327.67756.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW et al. Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1305–10. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Escolar E, Mintz GS, Popma J et al. Meta-analysis of angiographic versus intravascular ultrasound parameters of drug-eluting stent efficacy (from TAXUS IV, V, and VI). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:621–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakurai R, Ako J, Morino Y et al. Predictors of edge stenosis following sirolimus-eluting stent deployment (a quantitative intravascular ultrasound analysis from the SIRIUS trial). Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1251–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, Maehara A, Mintz GS et al. An integrated TAXUS IV, V, and VI intravascular ultrasound analysis of the predictors of edge restenosis after bare metal or paclitaxel-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witzenbichler B, Maehara A, Weisz G et al. Relationship between intravascular ultrasound guidance and clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stents: the assessment of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES) study. Circulation. 2013;129:463–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de la Torre Hernandez JM, Baz Alonso JA, Gomez Hospital JA et al. Clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance in drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary disease: pooled analysis at the patient-level of 4 registries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:244–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn JM, Kang SJ, Yoon SH et al. Meta-analysis of outcomes after intravascular ultrasound-guided versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation in 26,503 patients enrolled in three randomized trials and 14 observational studies. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1338–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang JS, Song YJ, Kang W et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents to improve outcome: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Ribamar Costa J Jr, Mintz GS, Carlier SG et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of drug-eluting stent expansion. Am Heart J. 2007;153:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abizaid A, Costa JR Jr, Bartorelli AL The ABSORB EXTEND study: preliminary report of the twelve-month clinical outcomes in the first 512 patients enrolled. EuroIntervention. 2014. Apr 29, [ePub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Dai J, Katoh O, Kyo E et al. Approach for chronic total occlusion with intravascular ultrasound-guided reverse controlled antegrade and retrograde tracking technique: single center experience. J Interv Cardiol. 2013;26:434–43. doi: 10.1111/joic.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi Y, Okazaki H, Mizuno K. Transvenous IVUS-guided percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusion: a novel strategy. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013. Jul 25, pp. E143–6. [PubMed]

- 45.Abizaid A, Mintz GS, Pichard AD et al. Clinical, intravascular ultrasound, and quantitative angiographic determinants of the coronary flow reserve before and after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:423–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishioka T, Amanullah AM, Luo H et al. Clinical validation of intravascular ultrasound imaging for assessment of coronary stenosis severity: comparison with stress myocardial perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1870–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takagi A, Tsurumi Y, Ishii Y et al. Clinical potential of intravascular ultrasound for physiological assessment of coronary stenosis: relationship between quantitative ultrasound tomography and pressure-derived fractional flow reserve. Circulation. 1999;100:250–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briguori C, Anzuini A, Airoldi F et al. Intravascular ultrasound criteria for the assessment of the functional significance of intermediate coronary artery stenoses and comparison with fractional flow reserve. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:136–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abizaid AS, Mintz GS, Mehran R et al. Long-term follow-up after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty was not performed based on intravascular ultrasound findings: importance of lumen dimensions. Circulation. 1999;100:256–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costa MA, Sabate M, Staico R et al. Anatomical and physiologic assessments in patients with small coronary artery disease: final results of the Physiologic and Anatomical Evaluation Prior to and After Stent Implantation in Small Coronary Vessels (PHANTOM) trial. Am Heart J. 2007;153(296):e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang SJ, Lee JY, Ahn JM et al. Validation of intravascular ultrasound-derived parameters with fractional flow reserve for assessment of coronary stenosis severity. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:65–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.959148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahn JM, Kang SJ, Mintz GS et al. Validation of minimal luminal area measured by intravascular ultrasound for assessment of functionally significant coronary stenosis comparison with myocardial perfusion imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cameron A, Kemp HG Jr, Fisher LD et al. Left main coronary artery stenosis: angiographic determination. Circulation. 1983;68:484–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fisher LD, Judkins MP, Lesperance J et al. Reproducibility of coronary arteriographic reading in the coronary artery surgery study (CASS). Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1982;8:565–75. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810080605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindstaedt M, Spiecker M, Perings C et al. How good are experienced interventional cardiologists at predicting the functional significance of intermediate or equivocal left main coronary artery stenoses? Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:254–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jasti V, Ivan E, Yalamanchili V et al. Correlations between fractional flow reserve and intravascular ultrasound in patients with an ambiguous left main coronary artery stenosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2831–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146338.62813.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abizaid AS, Mintz GS, Abizaid A et al. One-year follow-up after intravascular ultrasound assessment of moderate left main coronary artery disease in patients with ambiguous angiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:707–15. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fassa AA, Wagatsuma K, Higano ST et al. Intravascular ultrasound-guided treatment for angiographically indeterminate left main coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de la Torre Hernandez JM, Hernandez Hernandez F, Alfonso F et al. Prospective application of pre-defined intravascular ultrasound criteria for assessment of intermediate left main coronary artery lesions results from the multicenter LITRO study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wada T, Takayama K, Taoka T et al. Long-term treatment outcomes after intravascular ultrasound evaluation and stent placement for atherosclerotic subclavian artery obstructive lesions. Neuroradiol J. 2014;27:213–21. doi: 10.15274/NRJ-2014-10023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawasaki D, Fujii K, Fukunaga M Safety and Efficacy of Carbon Dioxide and Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Stenting for Renal Artery Stenosis in Patients With Chronic Renal Insufficiency. Angiology. 2014. Mar 5, [ePub ahead of Print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Higashimori A, Yokoi Y. Stent implantation for chronic total occlusion in the iliac artery using intravascular ultrasound-guided carbon dioxide angiography without iodinated contrast medium. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2013;28:415–8. doi: 10.1007/s12928-013-0183-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLafferty RB. The role of intravascular ultrasound in venous thromboembolism. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;29:10–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1302446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hislop S, Fanciullo D, Doyle A et al. Correlation of intravascular ultrasound and computed tomography scan measurements for placement of intravascular ultrasound-guided inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:1066–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thakrar PD, Petersen BD, Kaufman JA. Intravascular ultrasound for transvenous interventions. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:161–7. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hausmann D, Erbel R, Alibelli-Chemarin MJ et al. The safety of intracoronary ultrasound. A multicenter survey of 2207 examinations. Circulation. 1995;91:623–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Batkoff BW, Linker DT. Safety of intracoronary ultrasound: data from a Multicenter European Registry. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;38:238–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199607)38:3<238::AID-CCD3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li BH, Leung AS, Soong A et al. Hybrid intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography catheter for imaging of coronary atherosclerosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012 Feb;81:494–507. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carlier S, Didday R, Slots T A new method for real-time co-registration of 3D coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014. Mar 19, [ePub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Gurun G, Tekes C, Zahorian J et al. Single-chip CMUT-on-CMOS front-end system for real-time volumetric IVUS and ICE imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2014;61:239–50. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2014.6722610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]