Abstract

Total mercury (Hg; ppm dry weight) was measured in blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, collected from Narraganset Bay and adjacent coastal lagoons and tidal rivers (Rhode Island/Massachusetts, USA) from May to August 2006–2016. For juvenile crabs (21–79 mm carapace width, CW), total Hg was significantly greater in chelae muscle tissue (mean ± 1 SD = 0.32 ± 0.21 ppm; n = 65) relative to whole bodies (0.21 ± 0.16 ppm; n = 19), and irrespective of tissue-type, crab Hg was positively related to CW indicating bioaccumulation of the toxicant. Across a broader range of crab sizes (43–185 mm CW; n = 465), muscle Hg concentrations were significantly higher in crabs from the Taunton River relative other locations (0.71 ± 0.35 ppm and 0.20 ± 0.10 ppm, respectively). Spatial variations in crab Hg dynamics were attributed to habitat-specific Hg burdens of their prey, including bivalves, gastropods, polychaetes, and shrimp. Prey Hg, in turn, was directly related to localized sediment Hg and methylmercury conditions. Biota-sediment accumulation factors for crabs and prey were negatively correlated with sediment organic content, verifying that organically-enriched substrates reduce Hg bioavailability. From a human health perspective, frequent consumption of crabs from the Taunton River may pose a human health risk (23% of legal-size crabs exceeded US EPA threshold level); thus justifying spatially-explicit Hg advisories for this species.

Keywords: Mercury, Accumulation, Blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, Prey, Sediment, Consumption advisory

1. Introduction

Chemical contaminants are pervasive in many aquatic ecosystems, and their persistence in the environment may adversely affect the health of wildlife and humans (Fleeger et al., 2003; Johnston et al., 2015). Mercury (Hg) is specifically recognized as one of the most ubiquitous of these contaminants (US EPA, 1997), and chronic exposure to its organic form, methylmercury (MeHg), causes deleterious effects to the neurological, cardiovascular, immunological, and reproductive systems of biota (Hong et al., 2012). The extent of these health deficits depends on the magnitude and duration of MeHg exposure, which is affected by intra-specific life history traits (e.g., diet, growth, and longevity) and in situ physico-biogeochemical conditions that govern MeHg cycling in the environment (Chen et al., 2008). For the former, MeHg bioaccumulates in organismal tissues when the assimilation of the contaminant exceeds depuration rates (Evans et al., 2000). Moreover, MeHg biomagnifies across successive trophic levels, resulting in elevated MeHg concentrations in larger/older organisms and top-level consumers (Andres et al., 2002; Wiener et al., 2003; Olivero-Verbel et al., 2008; Reichmuth et al., 2010). From a human health perspective, MeHg exposure results from the consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish (Hightower and Moore, 2003; Taylor and Williamson, 2017), and MeHg typically constitutes > 95% of the total Hg burden in high trophic level species (Adams and Engel, 2014). Further, the majority of wild-caught fish and shellfish consumed by humans are of estuarine and marine origin (US EPA, 2002; Sunderland, 2007), thus emphasizing the need for toxicological research in coastal fisheries.

Estuarine and coastal habitats of the northeastern US receive substantial Hg loadings from atmospheric deposition, riverine inputs, and local point sources (Thompson, 2005; Chen et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2012). The majority of Hg that enters these aquatic ecosystems is deposited in sediments (Balcom et al., 2004), after which inorganic Hg is methylated to MeHg by anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacteria (Gilmour et al., 1992; Benoit et al., 2003). Methylation rates are often accelerated in estuarine and coastal sediments because these areas receive substantial anthropogenic inputs of inorganic Hg (Varekamp et al., 2003; Conaway et al., 2007; Fitzgerald et al., 2007) and maintain ideal physico-biogeochemical conditions for MeHg production and mobilization (e.g., frequent anoxia, elevated levels of organic material and sulfate, active bacterial communities, and optimal hydrodynamics at the sediment-water interface; Chen et al., 2008). Importantly, the causative factors that regulate MeHg dynamics in estuarine and coastal habitats vary over relatively small spatiotemporal scales (Chen et al., 2008). Thus, monitoring MeHg contamination in these ecosystems requires insight into localized biogeochemical conditions that affect MeHg production, mobilization, and subsequent incorporation and transfer in food webs (e.g., sediment characteristics and biotic life history traits), and, in addition, research must be conducted over requisite temporal scales (Mathieson et al., 1996; Sager, 2002). These efforts are necessary to evaluate the mechanisms underlying intra-specific MeHg contamination and to properly assess ecological and human health risks (Taylor et al., 2012).

The blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, is a portunid crustacean that has a documented range between the coastal waters of Nova Scotia and Argentina (Millikin and Williams, 1984). Maximal abundances of blue crabs have historically occurred in the Middle-Atlantic Bight, with only ephemeral populations at more northern latitudes (Johnson, 2015) – a geographic range delineated at its northern extent by the increased sensitivity of juvenile and mature female blue crabs to cold water temperatures (< 3 ºC; Rome et al., 2005; Hines et al., 2010). Recent empirical data, however, indicate a poleward expansion in the distribution of blue crabs, such that larger, permanent populations have been established in New England estuaries and coastal environments (Johnson, 2015). The apparent range extension of blue crabs is likely mediated by climate change and warmer water temperatures (i.e., increased over-wintering survival and growth; Rome et al., 2005; Hines et al., 2010; Hare et al., 2016), with potential implications to local food-web dynamics (Collier et al., 2014; Johnson, 2015). Blue crabs are dominant, opportunistic predators and scavengers throughout their geographic range, capable of altering benthic community structure (Hines et al., 1990). The broad dietary breadth of this species includes detritus, plant material, bivalves, gastropods, polychaetes, crustaceans, and small fish (Hines, 2007). Moreover, by functioning as a key epibenthic omnivore and prey resource for top-level consumers, blue crabs are critical to energy transfer across trophic levels within estuarine and nearshore communities (Hines, 2007).

In addition to their ecological significance, blue crabs support valuable commercial and recreational fisheries in the western Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. For example, from 2011–2015, the mean (± 1 standard deviation, SD) annual landings for the combined Atlantic and Gulf coast commercial fisheries equaled 74,764 ± 12,973 metric tons (hard-shell, soft-shell, and peelers), with the Chesapeake Bay region (Maryland and Virginia) accounting for 38.7 ± 4.4 % of the total landings (NMFS, 2017). Although harvest statistics are scarce for the blue crab recreational fishery, available data indicate that the recreational sector may comprise a large proportion of the overall fishery (8–79%; Stagg et al., 1992; Ashford and Jones, 2011), particularly in the northern reaches of the crab’s distribution (Jop et al., 1997). Further, the continued growth of blue crab populations at northern latitudes, e.g., southern New England (Collier et al., 2014; Johnson, 2015), may result in expanded fishery opportunities for this species and geographic region (Hines et al., 2010; Pinsky and Fogarty, 2012; Hare et al., 2016; Weatherdon et al., 2016).

The key trophodynamic role of blue crabs suggest they exert great influence on the fate of Hg in estuarine and coastal habitats. Further, given their commercial and recreational value, blue crabs may be an important source of Hg for human consumers. The principal objective of this study was to examine the total Hg content of blue crabs collected from a southern New England estuary: the Narragansett Bay [Rhode Island (RI) and Massachusetts (MA), USA] and adjacent coastal lagoons and tidal rivers. Blue crabs in this geographic area have recently experienced significant increases in abundance (Collier et al., 2014; Johnson, 2015), which may have important implications to local ecosystem Hg dynamics and human health, the latter owing to contamination in an emergent fishery (Hines et al., 2010). Specifically, this study sought to: (1) quantify total Hg concentrations in the chelae muscle tissue and whole bodies of blue crabs and analyze results relative to intra-specific life history traits, e.g., body size, gender, habitat use, and diet; (2) examine the effect of spatial variations in sediment characteristics on the Hg content of crabs and their prey; (3) evaluate crab Hg concentrations relative to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) criterion for the safe consumption of fishery products, and (4) address the implications of this research on the issuance of spatially-explicit consumption advisories.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area

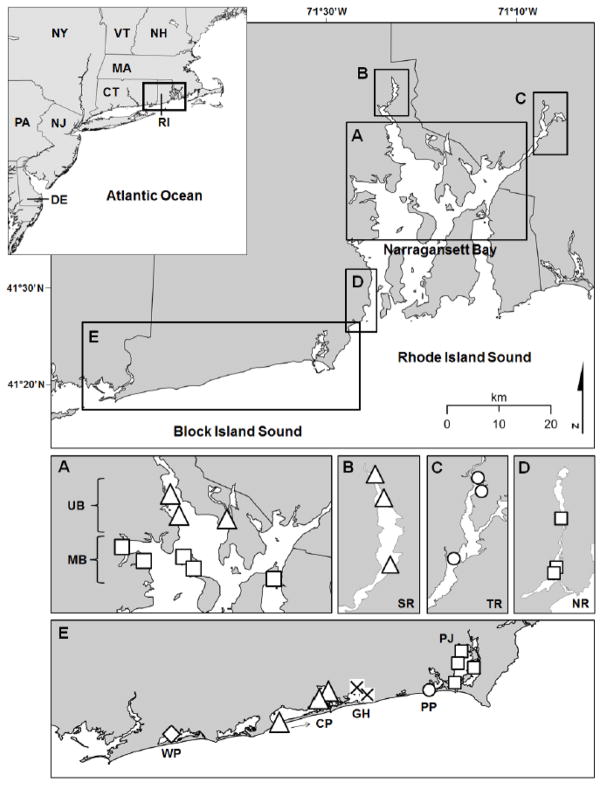

The Narragansett Bay estuary adjoins RI Sound at its mouth and extends northward into RI and MA (total area ~ 380 km2; mean depth ~ 7.8 m; Taylor et al., 2016 and references therein; Fig. 1). The geographically-complex system consists of the main estuary, sub-estuaries, bays, coves, and several tidally-influenced rivers, three of which were examined in this study and concurrent investigations (Taylor et al., 2012, Taylor et al., 2016): the Narrow River, Seekonk River, and Taunton River (mean depths ~ 1.3–2.0 m) located to the southwest, northwest, and northeast, respectively (Fig. 1). The main estuary is well-mixed with a marginal latitudinal salinity gradient (range ~ 24–33 ppt), whereas the tidal rivers have wider salinity ranges (< 2–30 ppt; Taylor et al., 2016). Annual water temperatures for the bay and tidal rivers range from 0.5 to 25 °C, and areas of the upper bay and rivers are subject to episodic hypoxia during the summer. Bay and riverine sediments are comprised mostly of fine-grained silts and clays, with fine sands common in the shoal areas of the upper and lower bay (Taylor et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

Map of the three habitats examined in this study, including the Narragansett Bay (Bay), coastal lagoons (Lagoon), and tidal rivers (River), with points denoting collection sites of blue crabs. For analysis purposes, the bay was partitioned into two locations: upper Bay (UB) and mid-Bay (MB). Lagoon locations included the Charlestown Pond (CP), Green Hill Pond (GH), Point Judith Pond (PJ), Potter’s Pond (PP), and Winnapaug Pond (WP), and river locations included the Narrow River (NR), Seekonk River (SR), and Taunton River (TR).

Nine coastal lagoons are located along the southern shore of RI, five of which were examined in this study: Charlestown Pond, Green Hill Pond, Point Judith Pond, Potter’s Pond, and Winnapaug Pond (areas ~ 1.8–6.9 km2; mean depths ~ 1.2–1.8 m; Taylor et al., 2016) (Fig. 1). The lagoons are separated from Block Island Sound by barrier spits (1–8 km long, 0.8–3.5 km wide), but are connected to the Sound by permanent breachways. Temperature and salinity ranges in the lagoons are similar to Narragansett Bay, and the sediments are dominated by sands and organic silts.

The principal source of mercury pollution in the Narragansett Bay and surrounding environments is anthropogenic atmospheric emissions/depositions, derived from solid waste incinerators and coal-fired power plants that reside outside of the impacted region (Thompson, 2005). The main industrial emitters of mercury in the immediate area are hospital incinerators and wastewater treatment sludge incinerators, with additional local sources originating from residential fuel combustion and open burning, automobile switches, dental applications, landfill leachate, and dredging operations that relinquish “legacy” mercury (i.e., repository mercury in estuarine sediments) (Thompson, 2005). The Narragansett Bay region has also been the subject of numerous mercury-related studies that have: (1) quantified total Hg and MeHg contamination in surface sediments (Taylor et al., 2012); (2) elucidated the effect of trophic processes on Hg dynamics in the estuarine food web (Piraino and Taylor, 2009; Payne and Taylor, 2010; Szczebak and Taylor, 2011; Taylor et al., 2014); (3) measured Hg concentrations in the tissues of recreationally and commercially valuable finfish (Taylor and Williamson, 2017); and (4) assessed Hg exposure in at-risk human populations owing to their dietary intake of local fishery resources (Taylor and Williamson, 2017). The outcomes of these synoptic examinations provide meaningful assessments of environmental and fish Hg contamination patterns that constitutes a human health risk.

2.2. Sample collection and preparation

Blue crabs were collected from the Narragansett Bay, coastal lagoons, and tidal rivers from May to August (2006–2016) using seines (Fig. 1), after which crabs were put on ice for transportation and frozen at 20 C in the laboratory. For a complete description of seine dimensions, net mesh sizes, and sample frequency across habitats, refer to the procedures described in Taylor et al. (2016). In the laboratory, partially thawed crabs were measured for carapace width (CW, mm), identified by gender based on abdomen morphology (Millikin and Williams, 1984), and muscle tissue was excised from both chelae (mainly propodus and carpus tissue). A sub-sample of crabs from the Taunton and Seekonk Rivers were also processed as whole bodies. All muscle and whole body samples were freeze-dried for at least 48 h (Labconco FreeZone 4.5-L Benchtop Freeze-Dry System), homogenized with clean stainless-steel spatulas, and stored at room temperature in borosilicate vials.

A concurrent investigation in the Narragansett Bay region examined the total Hg burden of low trophic level biota (Taylor et al., 2012), including species that are important prey for blue crabs. Specifically, through the visual analysis of stomach contents (n = 889), Taylor (unpublished data) identified four prey taxa that contributed substantially to the diet of local blue crabs (% volumetric contribution: bivalve ~ 27%; gastropod ~ 3%; polychaete ~ 6%; crustacean ~ 55%), and crab food habits did not markedly differ among habitats or locations (Fig. 1). Accordingly, Hg data for the following prey were used in the present study: bivalves (Ensis directus, Mercenaria mercenaria, Modiolus demissus, Mya arenaria, and Mytilus edulis), gastropods (Littorina littorina and Nassarius obsoletus), polychaetes (Nereididae and Glyceridae), and shrimp (Crangon septemspinosa and Palaemonetes pugio). Finally, spatially-explicit sediment characteristics were available for a subset of the sites where crabs were collected, including the mid- and upper bay and the Seekonk and Taunton Rivers (Fig. 1). Sediment data were accessed from concurrent studies (Taylor et al., 2012 and references therein) and included near surface (0–2 cm) sediment total Hg (mg/kg dry weight; ppm), MeHg (μg/kg dry weight; ppb), grain size < 63 μm (% silt-clay; Wentworth, 1922), and total organic content (TOC; % dry weight).

2.3. Mercury analysis

MeHg typically accounts for the majority of total Hg in the tissues of upper trophic level organisms, and this has been verified for blue crab muscle tissue (%MeHg = 98–100%) and whole bodies (93–97%) (Adams and Engel, 2014). To this end, for this study, total Hg was determined to be a reliable surrogate measurement for crab MeHg content. Specifically, total Hg concentrations (ppm dry weight) were measured in homogenized muscle-tissue and whole-body samples of crabs (~ 30–50 mg dry weight) using automated combustion atomic absorption spectrometry (DMA-80 Direct Hg Analyzer, Milestone, Inc., Shelton, Connecticut, USA), with a detection limit of 0.01 ng Hg (US EPA, 1998). The Hg analyzer was calibrated using certified reference materials (CRMs) of known Hg concentrations, and included solid standards (TORT-1: lobster hepatopancreas; DORM-2: dogfish muscle) and aqueous standards prepared by the National Research Council Canada, Institute of Environmental Chemistry (Ottawa, Canada) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (Gaithersburg, Maryland, USA), respectively. Calibration curves were highly significant (mean R2 = 1.00; range R2 = 0.99–1.00; p < 0.0001), and the recovery of independently analyzed samples of TORT-1, DORM-2, and PACS-2 (marine sediment) CRMs ranged from 90.4% to 104.4% (mean = 98.3%). All samples were analyzed as duplicates, and an acceptance criterion of 10% was implemented. Duplicate samples with < 10% error were averaged for subsequent analysis (mean absolute difference between duplicates = 3.2%). Samples with > 10% error were reanalyzed to achieve the acceptance criterion or were eliminated from further analysis. For additional quality control, blanks were analyzed every 10 samples to assess instrument accuracy and potential drift.

2.4. Data and statistical analysis

Mean differences in the total Hg of blue crabs as a function of tissue-type (chelae muscle and whole bodies) and river (Taunton and Seekonk Rivers) were analyzed with a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. Crabs used in this initial analysis were of consistent body sizes across the tissue-type treatment (21–79 mm CW) (Table 1). For a broader size range of crabs (43–185 mm CW), muscle total Hg was analyzed as a function of gender (male and female) and location (2 bay, 3 river, and 5 lagoon locations; Table 1; Fig. 1) using a two-way ANOVA model. The post hoc separation of mean differences in muscle total Hg across 10 levels of location were contrasted with a Ryan-Einot-Gabriel-Welsch (Ryan’s Q) multiple comparison test. Prior to each ANOVA test, total Hg data were log10-transformed to meet assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance. When data transformations were unsuccessful in achieving homoscedasticity, hypotheses were rejected at alpha levels lower than the p-values of the Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance (Underwood, 1981).

Table 1.

Mean ± 1 standard deviation of carapace width (CW; mm) and total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm dry weight) in the chelae muscle tissue of male and female blue crabs. Crabs were collected from three habitats: Narragansett Bay (Bay), coastal lagoons (Lagoon), and tidal rivers (River) across several locations (abbreviations defined in Fig. 1). Whole body total Hg concentrations are also reported for crabs collected from the Seekonk River (SR) and Taunton River (TR). Sample sizes = n.

| Habitat / Location |

n

|

CW

|

Hg

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

| Bay | |||||||||

| MB | 15 | 13 | 28 | 106.2 ± 29.7 | 118.5 ± 31.5 | 111.9 ± 30.6 | 0.174 ± 0.073 | 0.286 ± 0.125 | 0.226 ± 0.114 |

| UB | 14 | 2 | 16 | 143.0 ± 18.8 | 155.5 ± 2.1 | 144.6 ± 18.1 | 0.207 ± 0.078 | 0.212 ± 0.058 | 0.208 ± 0.074 |

| Lagoon | |||||||||

| CP | 2 | 1 | 3 | 95.5 ± 20.5 | 91.0 | 94.0 ± 14.7 | 0.100 ± 0.048 | 0.186 | 0.128 ± 0.060 |

| GH | 10 | 3 | 13 | 103.4 ± 32.8 | 113.3 ± 34.1 | 105.7 ± 31.9 | 0.083 ± 0.020 | 0.084 ± 0.018 | 0.083 ± 0.019 |

| PJ | 12 | 14 | 26 | 99.6 ± 26.0 | 86.9 ± 28.0 | 92.8 ± 27.3 | 0.201 ± 0.127 | 0.172 ± 0.079 | 0.185 ± 0.103 |

| PP | 6 | 2 | 8 | 111.3 ± 31.4 | 106.0 ± 63.6 | 110.0 ± 35.9 | 0.401 ± 0.152 | 0.415 ± 0.194 | 0.404 ± 0.148 |

| WP | 2 | 5 | 7 | 61.5 ± 19.1 | 61.4 ± 18.3 | 61.4 ± 16.8 | 0.207 ± 0.039 | 0.148 ± 0.047 | 0.165 ± 0.050 |

| River | |||||||||

| NR | 11 | 10 | 21 | 93.8 ± 19.8 | 90.0 ± 25.8 | 92.0 ± 22.3 | 0.180 ± 0.110 | 0.134 ± 0.100 | 0.158 ± 0.105 |

| SR | 165 | 33 | 198 | 111.6 ± 28.1 | 101.1 ± 25.3 | 109.8 ± 27.9 | 0.200 ± 0.078 | 0.197 ± 0.084 | 0.199 ± 0.078 |

| TR | 74 | 71 | 145 | 113.0 ± 32.0 | 97.0 ± 27.8 | 105.2 ± 31.0 | 0.792 ± 0.375 | 0.618 ± 0.301 | 0.707 ± 0.351 |

| SR (whole body) | – | – | 9 | – | – | 51.7 ± 18.2 | – | – | 0.072 ± 0.022 |

| TR (whole body) | – | – | 10 | – | – | 40.1 ± 14.6 | – | – | 0.333 ± 0.122 |

The effect of body size (mm CW) on crab total Hg across habitats were analyzed with least-squares exponential and linear regression models for muscle and whole-body data, respectively (Olivero-Verbel et al., 2008). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were also used to assess the effect of habitat on tissue-specific Hg bioaccumulation rates, with CW as the covariate and habitat as the discrete explanatory variable. Note for the regression and ANCOVA analyses, river data were separated into the Narrow/Seekonk Rivers and Taunton River, thus four levels of habitat were examined (i.e., bay, lagoon, Narrow/Seekonk Rivers, and Taunton River).

Finally, multiple linear regression analyses were used to assess the effects of several spatially-explicit biotic and abiotic variables on crab muscle total Hg, prey whole-body total Hg, and biota-sediment accumulation factors [BSAF(Hg) and BSAF(MeHg) = crab or prey total Hg/sediment total Hg or MeHg]; the latter is a convenient tool to assess linkages between organismal and environmental Hg contamination. The explanatory variables included in the regression models were prey total Hg (ppm dry weight; crab analysis only), sediment percent silt-clay and TOC content, sediment total Hg and MeHg normalized by grain size (sediment total Hg or MeHg/% silt-clay; Varekamp et al., 2000; Hortellani et al., 2005), and sediment percent MeHg (sediment total Hg/sediment MeHg). Prey and sediment data were available for 14 sites from the bay and Seekonk/Taunton Rivers (Table 2; Fig. 1). Further, site-specific prey Hg concentrations were calculated as means across prey taxa (i.e., bivalves, gastropods, polychaetes, and shrimp). For a complete description of species-specific prey size and Hg data, refer to Taylor et al. (2012). Small-sample, bias-corrected Akaike’s Information Criterion (AICc) and Akaike’s weights (wi) were used to evaluate and select the optimal regression model among 31 or 63 candidate models, depending on the response variable being analyzed (Burnham and Anderson, 2002):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where, ℒ is the likelihood function of the model parameters, n is the sample size, K is the number of regression parameters, and Δi is equal to AICc,i – AICc,min. The model with the smallest AICc value (AICc,min) had the most support, and the wi value quantified the probability that model i was the best among the candidate models.

Table 2.

Mean ± 1 standard deviation of prey whole-body total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm dry weight) and sediment total Hg (ppm dry weight), MeHg (ppb dry weight), grain size < 63 μm (% silt-clay), and total organic content (TOC; % dry weight). Data were previously reported in Taylor et al. (2012) and herein are summarized for two habitats: Narragansett Bay (Bay) and tidal rivers (River) across several locations (abbreviations defined in Fig. 1). Number of sites per location = n.

| Habitat / Location | n | Prey Hg | Sediment characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Bivalve | Gastropod | Polychaete | Shrimp | Hg | MeHg | %MeHg | % silt-clay | TOC | ||

| Bay | ||||||||||

| MB | 5 | 0.073 ± 0.026 | 0.056 ± 0.009 | 0.058 ± 0.023 | 0.054 ± 0.026 | 0.298 ± 0.133 | 2.083 ± 0.758 | 0.607 ± 0.160 | 36.4 ± 7.6 | 2.31 ± 0.85 |

| UB | 3 | 0.040 ± 0.015 | 0.039 ± 0.008 | 0.047 ± 0.011 | 0.039 ± 0.014 | 0.345 ± 0.095 | 1.644 ± 0.123 | 0.307 ± 0.083 | 27.4 ± 9.4 | 2.08 ± 0.16 |

| River | ||||||||||

| SR | 3 | 0.046 ± 0.001 | 0.066 ± 0.001 | 0.195 ± 0.066 | 0.057 ± 0.006 | 1.170 ± 0.334 | 0.800 ± 0.108 | 0.092 ± 0.076 | 41.4 ± 4.3 | 5.39 ± 1.69 |

| TR | 3 | 0.150 ± 0.030 | 0.300 ± 0.351 | 0.322 ± 0.280 | 0.212 ± 0.021 | 1.520 ± 0.086 | 1.839 ± 1.084 | 0.252 ± 0.037 | 27.6 ± 5.0 | 3.00 ± 0.01 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Blue crab mercury concentrations and bioaccumulation

A total of 484 intermolt blue crabs were collected from the Narragansett Bay and adjacent coastal lagoons and tidal rivers (Table 1), of which 465 individuals were used for muscle tissue analysis. The mean CW (±1 SD) of female crabs was 98.3 ± 29.5 mm (n = 154; range = 43–172 mm CW) and males were 111.3 ± 29.7 mm CW (n = 311; range = 44–185 mm CW). The majority of female crabs were immature (81.8%) according to their abdomen morphology (Millikin and Williams, 1984). Conversely, only 46.3% of the males were identified as juveniles, assuming sexual maturity is achieved at 110 mm CW (Guillory and Hein, 1997; Hines, 2007). A subset of crabs from the Taunton and Seekonk Rivers were also examined as whole bodies (n =19; Table 1), with a mean CW of 45.6 ± 17.0 mm (range = 21–79 mm CW). Gender was not recorded for these crabs, but they were categorized as juveniles owing to their small body sizes (Guillory and Hein, 1997; Hines, 2007).

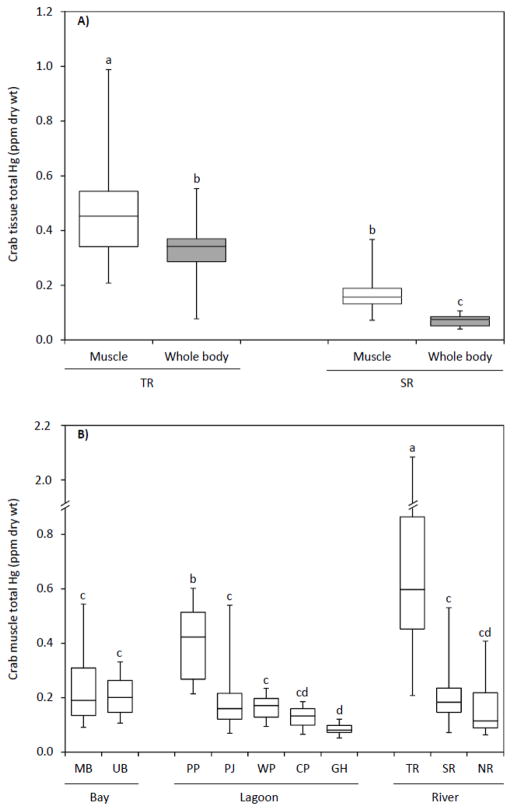

Crabs from the Taunton and Seekonk Rivers (21–79 mm CW) had significantly higher Hg concentrations in their chelae muscle tissue relative to whole bodies (mean muscle and whole body Hg: Taunton = 0.48 ± 0.20 ppm and 0.33 ± 0.12 ppm, respectively; Seekonk = 0.17 ± 0.06 ppm and 0.07 ± 0.02 ppm, respectively) (Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 2A). Similar tissue-specific Hg partitioning is reported in the literature, with concentrations consistently higher in muscle relative to whole bodies and the hepatopancreas (Table 4). Across a broader range of crab sizes (43–185 mm CW), muscle Hg content also varied significantly by location (Table 3). Crabs from the Taunton River had the highest mean Hg concentration (0.71 ± 0.35 ppm), followed by Potter’s Pond (0.40 ± 0.15 ppm), Seekonk River, upper and middle Narragansett Bay, and Point Judith and Winnapaug Ponds (0.20 ± 0.08 ppm), Narrow River and Charlestown Pond (0.15 ± 0.10 ppm), and Green Hill Pond (0.08 ± 0.02 ppm) (Table 1; Fig. 2B). The absolute range of Hg concentrations measured in this study (0.01–0.52 ppm wet weight assuming muscle has 75.1% moisture content; Küçükgülmez et al., 2006; Kuley et al., 2007; Zotti et al., 2016) are consistent with literature values for conspecifics and congeners from other geographic areas (muscle Hg on a ppm wet weight basis; Table 4), including Callinectes spp. from the North and South Atlantic Ocean (0.01–0.42 ppm), Gulf of Mexico (0.02–0.47 ppm), and Caribbean waters (0.01–1.32 ppm).

Table 3.

Summary statistics for two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models used to examine: blue crab total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm dry weight) as a function of tissue-type1 and river2; crab muscle Hg as a function of gender and location3; and effect of habitat4 and river2 on crab muscle and whole-body Hg bioaccumulation rates5, respectively.

| Factor (Model) | F (df) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Crab tissue Hg (ANOVA) | ||

| Tissue-type | 35.93 (1, 83) | < 0.0001 |

| River | 155.07 (1, 83) | < 0.0001 |

| Tissue-type × River | 4.82 (1, 83) | < 0.05 |

| Crab muscle Hg (ANOVA) | ||

| Gender | 0.11 (1, 464) | 0.741 |

| Location | 98.26 (9, 464) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender × Location | 2.51 (9, 464) | < 0.01 |

| Crab muscle Hg (ANCOVA) | ||

| CW × Habitat | 2.13 (3, 464) | 0.096 |

| CW | 73.04 (1, 464) | < 0.0001 |

| Habitat | 304.1 (3, 464) | < 0.0001 |

| Crab whole-body Hg (ANCOVA)5 | ||

| CW × River | 5.95 (1, 18) | < 0.05 |

Tissue-type = chelae muscle and whole-bodies

River = Taunton and Seekonk Rivers

Location = 2 bay, 5 lagoon, and 3 river locations (Fig. 1)

Habitat = bay, lagoon, Narrow/Seekonk Rivers, and Taunton River

Differences in Hg bioaccumulation were assessed by interaction effects between habitat/river and carapace width (CW). Significant interaction effect precluded further use of ANCOVA, and separate regression models were fit to each river dataset to examine Hg-CW relationships (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Total mercury (Hg) concentrations (ppm dry weight) of blue crabs as a function of tissue-type (chelae muscle and whole body) (A) and sampling locations across habitats (Bay, Lagoon, and River) (B). Box plots illustrate the median, 1st and 3rd quartiles, and maximum and minimum values. Different lowercase letters above box plots denote significant differences in mean values, whereas the same lowercase letters indicate non-significant results (Ryan’s Q multiple comparison test). Location abbreviations are defined in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Literature review of blue crab total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm wet weight). The following information is provided for each source document: Study regions and locations, sample size (n), crab carapace width (CW; mm) or life stage (LS), and tissue-type. Means ± 1 SD and ranges (in parentheses) are reported.

| Study region and location | n | CW or LS | Tissue total Hg

|

Literature source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Hepatopancreas | Whole body | ||||

| North Atlantic Ocean | ||||||

| Connecticut River (CT) | 15 | > 125 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | – | Jop et al. (1997) |

| Quinnipiac River (CT) | 25 | > 125 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | – | Jop et al. (1997) |

| Hudson River and Long Island bays (NY) | 112 | 139.2 ± 10.9 (92–174) | 0.042 ± 0.015 (0.014–0.150) | 0.025 ± 0.011 (0.004–0.140) | – | Skinner and Kane (2016)1 |

| Hudson-Raritan Estuary (NJ) | 12 | Adults | 0.445 ± 0.38 | – | – | Reichmuth et al. (2009)2 |

| Mullica River-Great Bay Estuary (NJ) | 10 | Adults | 0.167 ± 0.05 | – | – | Reichmuth et al. (2009)2 |

| Indian River Lagoon (FL) | 51 | 125.3 ± 29.4 (75–196) | 0.078 ± 0.065 (<0.025–0.416) | – | 0.055 ± 0.046 (<0.025–0.295) | Adams and Engel (2014) |

| Gulf of Mexico | ||||||

| Tampa Bay area (FL) | 5 | Adults | 0.094 ± 0.031 (0.04–0.12) | – | – | Lewis and Russell (2015)3 |

| Near-coastal Gulf (FL/AL) | 57 | Adults | 0.138 ± 0.096 (0.018–0.473) | – | – | Lewis and Chancy (2008) |

| Mobile-Tensaw River Delta (AL) | 10 | 49.9 ± 14.5 (29–75) | – | – | 0.013 ± 0.003 (0.009–0.019) | Farmer et al. (2010)3 |

| Pensacola Bay area (FL) | 28 | > 102 | 0.16 ± 0.04 (0.07–0.24) | 0.13 ± 0.21 (0.02–1.10) | – | Karouna-Renier et al. (2007)3 |

| Santa Rosa Sound (FL) | 18 | Adults | 0.193 ± 0.104 (0.050–0.473) | – | – | Lewis et al. (2004)4 |

| Caribbean Sea | ||||||

| Cartagena Bay (Colombia) | 153 | 119.7 ± 0.12 | 0.124 ± 0.011 (< 0.01–1.32) | – | – | Olivero-Verbel et al. (2008)5 |

| South Atlantic Ocean | ||||||

| Santos Estuary (Brazil) | 122 | 59.7 ± 1.2 | 0.071 ± 0.042 (< 0.001–0.12) | – | – | Bordon et al. (2012)6 |

Data are means (± 1 SD) calculated across eight locations, with 6–20 crabs per location

Variances are ± 1 standard error (SE)

Data are means (± 1 SD) based on composite analyses with 7–20 crabs per composite

Data are means (± 1 SD) calculated across three locations, with 3–9 sites per location, and Hg values were converted to wet weight assuming 83% water content (Lewis et al. 2004)

Data are means (± 1 SD) for two Callinectes spp. (C. sapidus and C. bocourti)

Data are for Callinectes danae; CW excludes lateral spines; mean (± 1 SD) Hg values calculated across 9 sites

Crab muscle total Hg concentrations were independent of gender, with the exception of individuals from the Taunton River and middle Narragansett Bay, thus explaining the significant gender-location interaction effect (Table 3). Male crabs from the Taunton River had higher Hg concentrations than females, whereas the opposite trend occurred in the mid-bay (Table 1). The effect of gender on crab Hg content was attributed to significant location-specific differences in male-female body sizes (Taunton: male CW > female CW; mid-bay: female CW > male CW; Student’s t-tests: p < 0.005) (Table 1); noting the existence of positive Hg-CW relationships in this study, as discussed below. Further, previous studies purport differences in the Hg content of blue crab muscle as a function of gender, which may be size-dependent (Skinner and Kane, 2016), but other investigations reported no effect of gender on tissue Hg burdens (Adams and Engel, 2014).

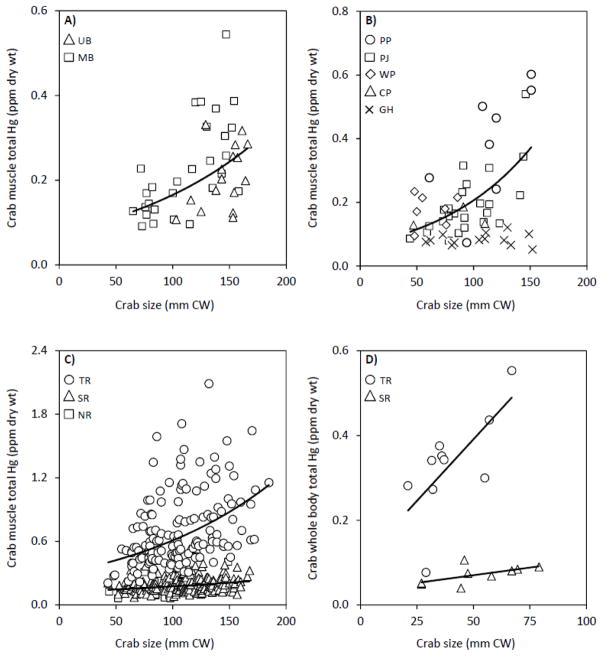

Total Hg concentrations in crab muscle and whole bodies were directly related to body size (Fig. 3), although the level of effect varied across habitats and locations (R2 = 0.07–0.48; Table 5). The observed Hg-CW relationships suggest blue crabs bioaccumulate Hg in most instances, as reported in previous laboratory investigations (Evans et al., 2000; Andres et al., 2002; Reichmuth et al., 2010). A positive interaction between crab size and total Hg in soft tissues was also documented in field-collected Callinectes spp. from Caribbean coastal waters (Olivero-Verbel et al., 2008). The accumulation of Hg in blue crabs is explained by the high assimilation efficiency of the toxicant (76%), while its subsequent retention in tissues could be attributed to slow excretion rates (Evans et al., 2000; Andres et al., 2002). Alternatively, Hg depuration through ecdysis may decrease throughout crab ontogeny, given that molting frequency is inversely related to body size and age (Millikin and Williams, 1984). Sequestering contaminants in the exoskeleton and molting the exuvia is an important mechanism for eliminating trace metals (e.g., cadmium, cooper, lead, zinc, and Hg) in the fiddler crab, Uca pugnax (Bergey, 2007; Bergey and Weis, 2007) and grass shrimp, Palaemonetes pugio (Keteles and Fleeger, 2001), although molting was a minor pathway for the removal of inorganic Hg and MeHg in the freshwater cladoceran, Daphnia magna (2–4% of total elimination; Tsui and Wang, 2004).

Fig. 3.

Total mercury (Hg) concentrations (ppm dry weight) in the chelae muscle tissue (A–C) and whole bodies (D) of blue crabs as a function of body size (carapace width, CW; mm) and habitat, including the Narragansett Bay (A), coastal lagoons (B), and tidal rivers (C–D). Least-squares exponential or linear regression models were fit to data and equations are presented in Table 5. Location abbreviations are defined in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Summary statistics for univariate exponential and linear regression models used to examine blue crab total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm dry weight) in chelae muscle tissue and whole bodies as a function of carapace width (CW; mm). Crabs were collected from three habitats: Narragansett Bay (Bay), coastal lagoons (Lagoon), and tidal rivers (River), and location abbreviations are defined in Figure 1.

| Habitat / Location | Regression model | F (df) | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bay | ||||

| MB and UB | log(Hg) = 3.37E−3 × CW − 1.119 | 16.75 (1, 43) | < 0.0005 | 0.285 |

| Lagoon | ||||

| CP, PJ, PP, and WP | log(Hg) = 5.06E−3 × CW − 1.192 | 27.31 (1, 43) | < 0.0001 | 0.394 |

| GH | log(Hg) = 1.06E−5 × CW − 1.088 | 1.28E−4 (1, 12) | 0.991 | 1.16E−5 |

| River | ||||

| NR/SR | log(Hg) = 1.65E−3 × CW − 0.923 | 16.38 (1, 218) | < 0.0001 | 0.070 |

| TR | log(Hg) = 3.17E−3 × CW − 0.532 | 42.85 (1, 144) | < 0.0001 | 0.231 |

| SR (whole body) | Hg = 7.22E−4 × CW + 0.034 | 4.19 (1, 8) | 0.080 | 0.375 |

| TR (whole body) | Hg = 5.80E−3 × CW + 0.101 | 7.35 (1, 9) | < 0.05 | 0.479 |

In contrast to the abovementioned findings, other field investigations reported no correlation between Hg and body size for blue crabs from the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, Alabama (Farmer et al., 2010) and Indian River Lagoon, Florida (Adams and Engel, 2014), as well as congeners from the Santiago and Blanco Rivers, Puerto Rico (Sastre et al., 1999). It is noteworthy that in this study whole-body Hg levels were positively related to CW for crabs from the Seekonk River (Fig. 3D), but this relationship was not significant at p < 0.05 (Table 5). Further, a more focused analysis of crabs from Green Hill Pond revealed no evidence of Hg bioaccumulation (Table 5; Fig. 3B). The existence and magnitude of Hg accumulation in blue crabs is presumably governed by a multitude of factors, including differences in localized Hg inputs (Thompson, 2005) and biogeochemical variables that alter MeHg production and mobilization (Chen et al., 2008). Moreover, spatially- and temporally-explicit physicochemical conditions and predator-prey dynamics can drastically affect intra-specific Hg accumulation and its trophic transfer (Chen et al., 2008).

The rate of Hg bioaccumulation in crab muscle did not differ among habitats (i.e., no habitat-CW interaction effect; Table 3). At a defined CW, however, crabs from the Taunton River had ~ 73% higher muscle Hg content than conspecifics from the other habitats. Results from this study also indicated that juvenile blue crabs from the Taunton River accumulate Hg in whole bodies at an accelerated rate relative to comparatively sized crabs from the Seekonk River (Table 3; Fig. 3D), as determined from the slopes of the Hg-CW regressions (Table 5). The comparison of these slope values predict that Taunton River crabs (β = 5.80E−3) accumulate Hg in whole-body tissues ~ 88% faster than individuals from the Seekonk River (β = 7.22E−4). The accumulation and resultant Hg burdens in Taunton River crabs are of ecological concern given that prior studies demonstrated negative biological effects under comparable Hg exposures (Weis et al., 1992; Engel and Thayer, 1998; Reichmuth et al., 2009). Adult blue crabs from polluted regions of the Hudson-Raritan Estuary, New Jersey, for example, had a mean muscle Hg content of 1.8 ± 1.5 standard error ppm (converted from wet weight) and experienced reduced predation efficiency on mobile prey (Reichmuth et al., 2009). Immediate and chronic exposure to environmental Hg also inhibits limb regeneration and ecdysis in crustaceans (Weis, 1976; Callahan and Weis, 1983; Weis et al., 1992) and reduces the survival of early-stage brachyuran crabs (Vernberg and Vernberg, 1974; Engel and Thayer, 1998). In the present study, spatially-explicit differences in prey Hg content and sediment features, as discussed below, may explain patterns in blue crab Hg contamination and bioaccumulation.

3.2. Mechanisms underlying spatial variations in blue crab and prey mercury concentrations and accumulation factors

A key objective of this study was to examine site-specific Hg contamination in blue crabs and representative prey (i.e., molluscs, polychaetes, and shrimp), as affected by localized substrate characteristics (Table 2). Defining biotic Hg dynamics on the basis of spatially-explicit geochemical conditions, however, is complicated by organismal movements and the possibility of exchange among different sites (Taylor et al., 2012). In this regard, blue crabs and their relatively sessile prey are ideal subjects because they exhibit high site fidelity in select habitats during the late spring and summer (Taylor et al., 2012). Specific to blue crabs, independent tagging studies verified that juveniles (< 85 mm CW) had limited movement (< 100 m) in post-dispersal nurseries during the spring and summer (Fitz and Weigert, 1991, 1992; van Montfrans et al., 1991; Davis et al., 2005). Similarly, adult male blue crabs (> 100 mm CW) do not migrate appreciably from residential summer habitats, with movements rarely exceeding 10 km (Oesterling and Adams, 1982; Hines, 2007). Post-copulatory females, in contrast, are migratory (Hines, 2007), initiating large-scale directional movements toward higher salinity spawning areas in the late summer and fall (Aguilar et al., 2005; Eggleston et al., 2015). It important to reiterate that 94.2% of the crabs in this study were juveniles (both genders) and adult males (Table 1). Therefore, given the time period (May to August) and crab characteristics (size and gender) relevant herein, we conclude that spatial distances are sufficient to dismiss crab exchange across study locations, thus enabling a site-specific analysis of Hg contamination.

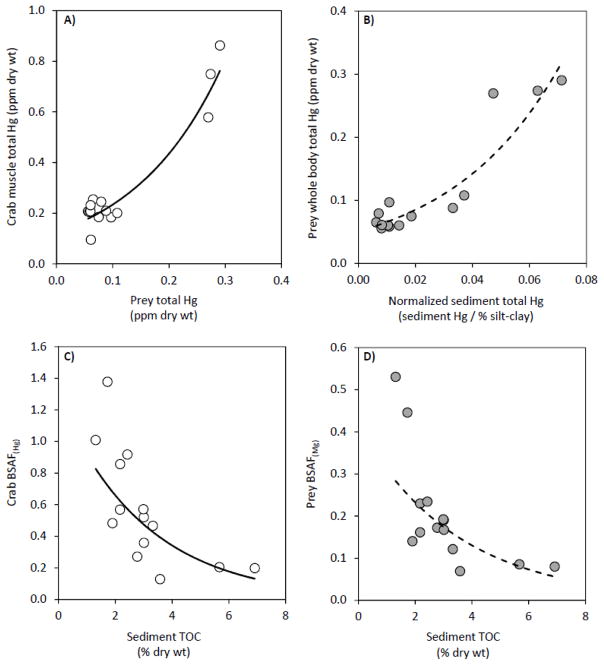

Total Hg concentrations in crab muscle were directly affected by spatially-explicit prey Hg conditions (Table 2; Fig. 4A). Specifically, prey Hg accounted for ~ 83% of the variation in crab Hg content (Table 6), which was mainly attributed to contaminated prey from the Taunton River relative to other locations, irrespective of taxa (mean prey Hg: Taunton = 0.25 ± 0.17; Other locations = 0.06 ± 0.02 ppm; Table 2). These results suggest that diet is the primary route of Hg exposure for blue crabs and proximate contact with contaminated sediments (i.e., absorption) is of lesser importance, as reported elsewhere for Callinectes sp. and the shore crab Carcinus maenas (Evans et al., 2000; Pereira et al., 2006; Reichmuth et al., 2010). Moreover, previous studies document that tissue Hg burdens in blue crabs and other portunid crabs are highly responsive to localized contaminant sources (Pereira et al., 2006; Lewis and Chancy, 2008; Oliverso-Verbel et al., 2008; Reichmuth et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Total mercury (Hg) concentrations (ppm dry weight) in the chelae muscle tissue of blue crabs and whole bodies of representative prey, and their respective biota-sediment accumulation factors (BSAF(Hg) = crab or prey total Hg/sediment total Hg), as a function of prey total Hg (A), normalized sediment total Hg (sediment total Hg/% silt-clay) (B), and sediment total organic content (TOC; % dry weight) (C–D). Least-squares exponential regression models were fit to the data.

Table 6.

Summary statistics for small-sample, bias-corrected Akaike’s Information Criterion (AICc) and Akaike’s weights (wi) used to select optimal multivariate regression models. Regression analyses were used to predict blue crab chelae muscle and prey whole body total mercury concentrations (Hg; ppm dry weight) and biota-sediment accumulation factors [BSAF(Hg) = crab or prey total Hg/sediment Hg] as a function of several explanatory variables, including normalized sediment total Hg (sediment Hg/% silt-clay), normalized sediment methylmercury concentrations (sediment MeHg/% silt-clay), and sediment total organic carbon (TOC; % dry weight). Positive (+) and negative (−) symbols in parentheses after each explanatory variable denote their directional influence on each response variable.

| Response variable | Optimal model | F (df) | p | R2 | AICc | wi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crab Hg | Prey Hg (+) | 59.0 (1, 13) | < 0.0001 | 0.831 | −59.2 | 0.23 |

| Prey Hg | Normalized sediment Hg (+) | 61.3 (2, 13) | < 0.0001 | 0.918 | −66.1 | 0.36 |

| Normalized sediment MeHg (+) | ||||||

| Crab BSAF(Hg) | Sediment TOC (−) | 9.6 (2, 13) | < 0.005 | 0.535 | −42.1 | 0.29 |

| Prey BSAF(Hg) | Sediment TOC (−) | 15.8 (1, 13) | < 0.005 | 0.569 | −46.9 | 0.45 |

Spatial patterns in prey total Hg varied in accordance with environmental toxicant gradients (Table 2), such that whole-body Hg burdens were significantly related to sediment mercury conditions (Table 6; Fig. 4B). Note that prior to statistical analyses, sediment total Hg and MeHg data were normalized a posteriori by silt-clay content to minimize the effects of this confounding factor (Varekamp et al., 2000; Hortellani et al., 2005). Accordingly, multiple linear regression analyses revealed that prey Hg was directly associated with normalized sediment Hg and MeHg (β = 11.1 and 3.1, respectively; Table 6); however, sediment Hg explained substantially more variation in prey Hg (partial R2-values for sediment Hg and MeHg = 0.865 and 0.052, respectively). The relatively weak association between prey total Hg and sediment MeHg was previously noted by Taylor et al. (2012), and attributed to MeHg comprising a small and variable percentage of the total Hg burden in low trophic level species (%MeHg < 40%; Chen et al., 2009), including the molluscs, polychaetes, and shrimp analyzed in this study. Conversely, research in other estuarine and coastal environments document strong linkages between biota-sediment total Hg concentrations (Hammerschmidt and Fitzgerald, 2004; Taylor et al., 2012), indicating that benthic fauna of low-trophic status have secondary exposure to inorganic Hg and MeHg through an intimate contact with sediments and pore water, as well as the ingestion of sediments and detritus (Reynoldson, 1987; Locarnini and Presley, 1996; Lawrence and Mason, 2001). With respect to the environmental toxicant gradients in this study, the Taunton River had excessive concentrations of sediment total Hg (mean sediment total Hg: Taunton = 1.52 ± 0.09 ppm; Other locations = 0.55 ± 0.44 ppm) and moderate MeHg contamination (mean sediment MeHg: Taunton = 1.84 ± 1.08 ppb; Other locations = 1.61 ± 0.72 ppb) (Table 2). The elevated mercury content of surface sediments from the Taunton River and, to a lesser extent, Seekonk River was attributed to their close proximity to urbanized, residential areas in MA and RI, respectively (Taylor et al., 2012).

The uptake of sediment mercury (total Hg and MeHg) by blue crabs and prey was evaluated using BSAF metrics. Spatial variations in sediment organic matter significantly affected the linkage between organismal and sediment total Hg concentrations, i.e., BSAF(Hg) (Table 2). Sediment TOC specifically explained ~ 54% and 57% of the variation in total Hg-based accumulation factors for crabs and prey, respectively, and the estimated slope coefficients were negative in each regression model (β = −0.142 and −0.125, respectively) (Table 6; Fig. 4CD). Mercury readily binds to organic matter, which subsequently reduces its bioavailability (Chen et al., 2008). Accordingly, BSAF(Hg) are predictably low in habitats with organic-rich sediments, as confirmed in several field and laboratory investigations (Taylor et al., 2012 and references therein). This mechanism, in particular, explicates the low Hg content of biota from the Seekonk River, with the exception of polychaetes (mean Hg: polychaete = 0.20 ± 0.07 ppm; Other prey = 0.06 ± 0.002 ppm). Seekonk River sediments were moderately contaminated with a mean Hg content of 1.2 ± 0.3 ppm; yet at this location, the incorporation of sediment-derived Hg into biotic receptors was minimal due to the substrate’s simultaneously high organic content (mean TOC: Seekonk = 5.4 ± 1.7 % dry weight; Other locations = 2.5 ± 0.3 % dry weight) (Table 2). In this study, with respect to BSAF(MeHg), no explanatory variables included in the regression analyses were significant at p < 0.05. The dissociation between BSAF(MeHg) and spatially-explicit sediment characteristics may be an artifact of sediment MeHg accounting for a marginal percentage of total Hg (mean sediment %MeHg = 0.4 ± 0.2%; Table 2).

3.3. Blue crab mercury concentrations relative to US EPA threshold levels and implications for consumption advisories

In this study, 131 blue crabs had carapace widths greater than their minimum size for legal recreational harvest (≥127 mm CW; MA EOEEA, 2017; RI DEM, 2017). For these legally harvestable crabs, the total Hg of their muscle tissue was statistically compared to the US EPA Hg threshold level (0.3 ppm wet weight), noting that dietary intake of Hg beyond this criterion may cause deleterious effects to human health (US EPA, 1997). Irrespective of habitat or location, mean Hg concentrations of legal-size crabs were significantly lower than the US EPA criterion of 0.3 ppm (One-sample t-tests: t-values = −48.69 to −5.06; p < 0.0001). Further, Hg-CW regression models revealed that crabs from the Taunton River had total Hg concentrations exceeding 0.3 ppm after reaching 192 mm CW (Table 5 and Fig. 3), whereas crabs from other habitats only approached the US EPA threshold at body sizes well beyond their maximum achievable CW (Hines, 2007).

The Rhode Island Department of Health (RI DOH) establishes Hg consumption advisories to inform the public of the potential health risks of eating fish and shellfish (RI DOH, 2017). The RI DOH protocol for implementing advisories is described in Taylor and Williamson (2017) and is based on the percentage of fish and shellfish samples (of legal size) that have Hg concentrations exceeding 0.3 ppm wet weight. Specifically, no advisories are issued when < 10% of the samples exceed 0.3 ppm. The general population is advised to limit fish and shellfish consumption to 1 meal/week and 1 meal/month when 10–30% and 30–50% of the samples exceed 0.3 ppm, respectively, or to not consume any fish or shellfish when > 50% of the samples exceed this threshold. Stricter guidelines are issued for women of childbearing age (18–45 years of age) and young children (< 14 years of age), who are advised to avoid all fish and shellfish consumption when > 10% of the samples exceed 0.3 ppm. According to RI DOH guidelines and Hg data presented herein, a consumption advisory is warranted for blue crabs from the Taunton River (9 of 39 or 23.1% of samples > 0.3 ppm; Advisories: general population = 1 meal/week; women and children = do not eat). Conversely, total Hg concentrations were relatively low for crabs from other locations (0 of 92 or 0% of samples > 0.3 ppm), which justifies their exclusion from state-specific consumption advisories.

4. Summary

Blue crab populations have recently increased in southern New England coastal waters, which will likely elevate their fishery status in the region. With an emerging crab fishery, research is needed to quantify contaminant levels in this species. In this study, total Hg concentrations were measured in the chelae muscle tissue and whole bodies of crabs from the Narragansett Bay and immediate coastal lagoons and tidal rivers. Crabs exhibited tissue-specific Hg partitioning, with concentrations higher in muscle relative to whole bodies. Total Hg in both tissue-types varied significantly across habitats, and further, crab Hg content was often directly related to CW. This Hg-size relationship denotes bioaccumulation and results from the disproportional uptake of Hg relative to low depuration rates; the latter possibly mediated by less frequent ecdysis throughout crab ontogeny. Dietary intake is ostensibly the primary route of Hg exposure in blue crabs, and individuals from the Taunton River had elevated muscle Hg content because of their consumption of localized, Hg-enriched prey, including molluscs, polychaetes, and shrimp. Conversely, prey whole-body Hg burdens were positively related to normalized sediment total Hg and MeHg concentrations, indicating that adsorption of contaminants via direct substrate contact is an important exposure pathway for benthic fauna of lower trophic status. The efficacy with which mercury is transferred from sediments to biotic receptors is routinely assessed using BSAFs. In this study, for crabs and prey, BSAFs calculated with sediment total Hg data were negatively related to sediment TOC, indicating that high amounts of organic matter in the substrate reduces Hg bioavailability. Finally, from a human health perspective, the majority of blue crabs analyzed in this study were categorized as low risk. Frequent consumption of crabs from the Taunton River, however, may adversely affect human health, and therefore, spatially-explicit Hg advisories are warranted for this species.

Research highlights.

Blue crabs had tissue-specific and habitat-specific mercury (Hg) concentrations.

Crab Hg was positively related to carapace width indicating bioaccumulation.

Spatial variations in crab Hg were attributed to localized prey Hg conditions.

Sediment organic content reduced Hg bioavailability for crabs and prey.

Frequent consumption of Taunton River crabs may pose a human health risk.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. McNamee, J. Lake, and N. Ares (Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, Jamestown, RI) and numerous undergraduate research assistants (Roger Williams University, Bristol, RI) for their efforts in field sampling and tissue preparations. The project described herein was supported in part by the Rhode Island (RI) National Science Foundation Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, the RI Science & Technology Advisory Council Research Alliance Collaborative Grant, the RWU Foundation Fund Based Research Grant, and by Award P20RR016457 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams DH, Engel ME. Mercury, lead, and cadmium in blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, from the Atlantic coast of Florida, USA: A multipredator approach. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2014;102:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar R, Hines AH, Wolcott TG, Wolcott DL, Kramer MA, Lipcius RN. The timing and route of movement and migration of post-copulatory female blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, from the upper Chesapeake Bay. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2005;319:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Andres S, Laporte JM, Mason RP. Mercury accumulation and flux across the gills and the intestine of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) Aquat Toxicol. 2002;56:303–320. doi: 10.1016/s0166-445x(01)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford JR, Jones CM. Survey of the blue crab recreational fishery in Maryland, 2009. Final Report to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources; Annapolis, MD: 2011. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Balcom PH, Fitzgerald WF, Vandal GM, Lamborg CH, Rolfhus KR, Langer CS, et al. Mercury sources and cycling in the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. Mar Chem. 2004;90:53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JM, Gilmour CC, Heyes A, Mason RP, Miller CL. Biogeochemistry of Environmentally Important Trace Elements. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2003. Geochemical and biological controls over methylmercury production and degradation in aquatic ecosystems; pp. 262–297. ACS Symposium Series 835. [Google Scholar]

- Bergey LL. PhD dissertation. Rutgers University; Newark: 2007. Behavioral ecology and population biology in populations of fiddler crabs Uca pugnax (Smith) on the New Jersey coast. [Google Scholar]

- Bergey LL, Weis JS. Molting as a mechanism of depuration of metals in the fiddler crab, Uca pugnax. Mar Environ Res. 2007;64:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordon ICAC, Sarkis JES, Tomás ARG, Scalco A, Lima M, Hortellani MA, Andrade NP. Assessment of metal concentrations in muscles of the blue crab, Callinectes danae S., from the Santos Estuarine System. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2012;89:484–488. doi: 10.1007/s00128-012-0721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: a Practical Information-Theoretical Approach. 2. Springer-Verlag; New York. New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan P, Weis JS. Methylmercury effects on regeneration and ecdysis in fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator, U. pugnax) after short-term and chronic pre-exposure. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1983;12:707–714. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Amirbahman A, Fisher N, Harding G, Lamborg C, Nacci D, Taylor D. Methylmercury in marine ecosystems: Spatial patterns and processes of production, bioaccumulation, and biomagnification. EcoHealth. 2008;5:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10393-008-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Dionne M, Mayes BM, Ward DM, Sturup S, Jackson BP. Mercury bioavailability and bioaccumulation in estuarine food webs in the Gulf of Maine. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:1804–1810. doi: 10.1021/es8017122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier JL, Fitzgerald SP, Hice LA, Frisk MG, McElroy AE. A new PCR-based method shows that blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun)) consume winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus (Walbaum)) PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e85101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway CH, Ross JRM, Looker R, Mason RP, Flegal AR. Decadal mercury trends in San Francisco estuary sediments. Environ Res. 2007;105:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JLD, Young-Williams AC, Hines AH, Zohar Y. Assessing the potential for stock enhancement in the case of the Chesapeake Bay blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2005;62:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston DB, Millstein E, Plaia G. Timing and route of migration of mature female blue crabs in a tidal estuary. Biol Lett. 2015;11:20140936. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel DW, Thayer GW. Effects of habitat alteration on blue crabs. J Shellfish Res. 1998;17:579–585. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW, Kathman RD, Walker WW. Trophic accumulation and depuration of mercury by blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) and pink shrimp (Penaeus duorarum) Mar Environ Res. 2000;49:419–34. doi: 10.1016/s0141-1136(99)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TM, Wright RA, DeVries DR. Mercury concentration in two estuarine fish populations across a seasonal salinity gradient. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2010;139:1896–1912. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz HC, Wiegert RG. Utilization of the intertidal zone of a salt marsh by the blue crab Callinectes sapidus: Density, return frequency, and feeding habits. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1991;76:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz HC, Wiegert RG. Local population dynamics of estuarine blue crabs: Abundance, recruitment and loss. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1992;87:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald WF, Lamborg CH, Hammerschmidt CR. Marine biogeochemical cycling of mercury. Chem Rev. 2007;107:641–662. doi: 10.1021/cr050353m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeger JW, Carman KR, Nisbet RM. Indirect effects of contaminants in aquatic ecosystems. Sci Total Environ. 2003;317:207–233. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour CG, Henry EA, Mitchell R. Sulfate stimulation of mercury methylation in freshwater sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:2281–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Guillory V, Hein S. Sexual maturity in Louisiana blue crabs. Proceedings of the Louisiana Academy of Science. 1997;59:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt CR, Fitzgerlad WF. Geochemical controls on the production and distribution of methylmercury in near-shore marine sediments. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:1487–1495. doi: 10.1021/es034528q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare JA, Morrison WE, Nelson MW, Stachura MM, Teeters EJ, Griffis RB, et al. A vulnerability assessment of fish and invertebrates to climate change on the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0146756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower JM, Moore D. Mercury levels in high-end consumers of fish. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines AH. Ecology of juvenile and adult blue crabs. In: Kennedy VS, Cronin LE, editors. The blue crab Callinectes sapidus. Maryland Sea Grant College Program; College Park, Maryland: 2007. pp. 565–654. [Google Scholar]

- Hines AH, Haddon AM, Wiechert LA. Guild structure and foraging impact of blue crabs and epibenthic fish in a subestuary of Chesapeake Bay. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1990;67:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hines AH, Johnson EG, Darnell MZ, Rittschof D, Miller TJ, Bauer LJ, Rodgers P, Aguilar R. Predicting effects of climate change on blue crabs in Chesapeake Bay. In: Kruse GH, Eckert GL, Foy RJ, Lipcius RN, Sainte-Marie B, Stram DL, Woodby D, editors. Biology and Management of Exploited Crab Populations under Climate Change. Alaska Sea Grant, University of Alaska Fairbanks; 2010. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hong YS, Kim YM, Lee KE. Methylmercury exposure and health effects. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45:353–363. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.6.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortellani MA, Sarkisa JES, Bonetti J, Bonetti C. Evaluation of mercury contamination in sediments from Santos-São Vicente Estuarine System, São Paulo State, Brazil. J Braz Chem Soc. 2005;16:1140–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DS. The savory swimmer swims north: A northern range extension of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus? J Crustacean Biol. 2015;35:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston EL, Mayer-Pinto M, Crowe TP. Chemical contaminant effects on marine ecosystem functioning. J Appl Ecol. 2015;52:140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jop KM, Biever RC, Hoberg JR, Shepherd SP. Analysis of metals in blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, from two Connecticut estuaries. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1997;58:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s001289900336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karouna-Renier NK, Snyder RA, Allison JG, Wagner MG, Ranga Rao K. Accumulation of organic and inorganic contaminants in shellfish collected in estuarine waters near Pensacola, Florida: Contamination profiles and risks to human consumers. Environ Pollut. 2007;145:474–488. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keteles KA, Fleeger JW. The contribution of ecdysis to the fate of copper, zinc, and cadmium in grass shrimp, Palaemontes pugio Holthius. Mar Pollut Bull. 2001;42:1397–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(01)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küçükgülmez A, Çelik M, Yanar Y, Ersoy B, Çikrikçi M. Proximate composition and mineral contents of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) breast meat, claw meat and hepatopancreas. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2006;41:1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Kuley E, Özoul F, Özogul Y, Olgunoglu AI. Comparison of fatty acid and proximate compositions of the body and claw of male and female blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) from different regions of the Mediterranean coast. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;59:573–580. doi: 10.1080/09637480701451201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AL, Mason RP. Factors controlling the bioaccumulation of mercury and methylmercury by the estuarine amphipod Leptocheirus plumulosus. Environ Pollut. 2001;111:217–231. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(00)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Chancy C. A summary of total mercury concentrations in flora and fauna near common contaminant sources in the Gulf of Mexico. Chemosphere. 2008;70:2016–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Quarles RL, Dantin DD, Moore JC. Evaluation of a Florida coastal golf complex as a local and watershed source of bioavailable contaminants. Mar Pollut Bull. 2004;48:254–262. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locarnini SJP, Presley BJP. Mercury concentrations in benthic organisms from contaminated estuary. Mar Environ Res. 1996;41:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- MA EOEEA (Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs) [Accessed 29 June 2017];Recreational crab regulations. 2017 http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/dmf/laws-and-regulations/recreational-regulations/

- Mathieson S, George SG, McLusky DS. Temporal variation of total mercury concentrations and burdens in the liver of eelpout Zoarces viviparous from the Forth Estuary, Scotland: implications for mercury biomonitoring. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1996;138:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Millikin MR, Williams AB. Synopsis of biological data on the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No 138, NOAA Tech Rept NMFS. 1984;51:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) [Accessed 9 Jun 2017];Fisheries Statistics Division. 2017 http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/st1/

- Oesterling MJ, Adams CA. Migration of blue crabs along Florida’s Gulf Coast. In: Perry HM, Van Engel WA, editors. Proceedings of the Blue Crab Colloquium. Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Publication 7. Ocean Springs; Mississippi: 1982. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Olivero-Verbel J, Johnson-Restrepo B, Baldiris-Avila R, Güette-Fernández J, Magallanes-Carreazo E, Vanegas-Ramírez L, Kunihiko N. Human and crab exposure to mercury in the Caribbean coastal shoreline of Colombia: Impact from an abandoned chlor-alkali plant. Environ Int. 2008;34:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne EJ, Taylor DL. Effects of diet composition and trophic structure on mercury bioaccumulation in temperate flatfishes. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2010;58:431–443. doi: 10.1007/s00244-009-9423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira E, Abreu SN, Coelho JP, Lopes CB, Pardal MA, Vale C, Duarte AC. Seasonal fluctuations of tissue mercury contents in the European shore crab Carcinus maenas from low and high contamination areas (Ria de Aveiro, Portugal) Mar Pollut Bull. 2006;52:1450–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky ML, Fogarty M. Lagged social-ecological responses to climate and range shifts in fisheries. Climatic Change. 2012;115:883–891. [Google Scholar]

- Piraino MN, Taylor DL. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of mercury in striped bass (Morone saxatilis) and tautog (Tautoga onitis) from the Narragansett Bay (Rhode Island, USA) Mar Environ Res. 2009;67:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmuth JM, Roudez R, Glover TG, Weis JS. Differences in prey capture behavior in populations of blue crab (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun) from contaminated and clean Estuaries in New Jersey. Estuar Coast. 2009;32:298–308. [Google Scholar]

- Reichmuth JM, Weis P, Weis JS. Bioaccumulation and depuration of metals in blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun) from a contaminated and clean estuary. Envrion Pollut. 2010;158:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynoldson T. Interactions between sediment contaminants and benthic organisms. Hydrobiologia. 1987;149:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- RI DEM (Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management) [Accessed 29 June 2017];Marine fisheries minimum sizes & possession limits. 2017 http://www.dem.ri.gov/programs/bnatres/fishwild/mfsizes.htm.

- RI DOH (Rhode Island Department of Health) [Accessed 29 June 2017];Mercury poisoning: About fish. 2017 http://www.health.ri.gov/healthrisks/poisoning/mercury/about/fish/

- Rome MS, Young-Williams AC, Davis GR, Hines AH. Linking temperature and salinity tolerance to winter mortality of Chesapeake Bay blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2005;319:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sager DR. Long-term variation in mercury concentrations in estuarine organisms with changes in releases into Lavaca Bay, Texas. Mar Pollut Bull. 2002;44:807–815. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre MP, Reyes P, Ramos H, Romero H, Rivera J. Heavy metal bioaccumulation in Puerto Rican blue crabs (Callinectes spp) Bull Mar Sci. 1999;64:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner LC, Kane MW. Cadmium, mercury and PCB residues in blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) taken from the Hudson River and New York’s marine district. Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; Albany, NY: 2016. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Stagg C, Holloway M, Rugolo L, Knotts K, Kline L, Logan D. Evaluation of the 1990 recreational, charter boat, and commercial striped bass fishing surveys and design of a recreational blue crab survey. Chesapeake Bay Research and Monitoring Division; 1992. CBRM-Fr-94-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland EM. Mercury exposure from domestic and imported estuarine and marine fish in the U.S. seafood market. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:235–242. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczebak JS, Taylor DL. Ontogenetic patterns in bluefish Pomatomus saltatrix feeding ecology and the effect on mercury biomagnification. Environ Chem Toxicol. 2011;30:1447–1458. doi: 10.1002/etc.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, Kutil NJ, Malek AJ, Collie JS. Mercury bioaccumulation in cartilaginous fishes from Southern New England coastal waters: Contamination from a trophic ecology and human health perspective. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;99:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, Linehan JC, Murray DW, Prell WL. Indicators of sediment and biotic mercury contamination in a southern New England estuary. Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64:807–819. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, McNamee J, Lake J, Gervasi CL, Palance DG. Juvenile winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) and summer flounder (Paralichthys dentatus) utilization of Southern New England nurseries: Comparisons among estuarine, tidal river, and coastal lagoon shallow-water habitats. Estuar Coast. 2016;39:1505–1525. doi: 10.1007/s12237-016-0089-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, Williamson PR. Mercury contamination in Southern New England coastal fisheries and dietary habits of recreational anglers and their families: Implications to human health and issuance of consumption advisories. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;114:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MR. Final report of the Rhode Island Commission on mercury reduction and education. Pursuant to RIGL §23–24. 2005 Submitted to Governor Donald L. Carcieri and the Rhode Island General Assembly, April 2005. at < http://www.dem.ri.gov/topics/pdf/hgcomrep.pdf >.

- Tsui MTK, Wang WX. Uptake and elimination routes of inorganic mercury and methylmercury in Daphnia magna. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:808–816. doi: 10.1021/es034638x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood AJ. Techniques of analysis of variance in experimental marine biology and ecology. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev. 1981;19:513–605. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) Mercury study report to Congress. Fate and Transport of Mercury in the Environment. I-VII. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1997. EPA-452/R-97-005. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) EPA Method 7473 Report. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1998. Mercury in solids and solutions by thermal decomposition, amalgamation, and atomic absorption spectrophotometry. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) Estimated per capita fish consumption in the United States. EPA-821-C-02-003. US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C., USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Varekamp JC, Buchholtz ten Brink MR, Mecray EL, Kreulen B. Mercury in Long Island Sound sediments. J Coast Res. 2000;16:613–626. [Google Scholar]

- Varekamp JC, Kreulen B, Brink MRB, Mecray EL. Mercury contamination chronologies from Connecticut wetlands and Long Island Sound sediments. Environ Geol. 2003;43:268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg FJ, Verberg W. Multiple environmental factor effects on physiology and behavior of the fiddler crab, Uca pugilator. In: Vernberg FJ, Vernberg WB, editors. Pollution and Physiology of Marine Organisms. Academic Press; New York: 1974. pp. 381–425. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherdon LV, Magnan AK, Rogers AD, Sumaila UR, Cheung WWL. Observed and projected impacts of climate change on marine fisheries, aquaculture, coastal tourism, and human health: An update. Front Mar Sci. 2016;3:48. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weis JS. The effects of mercury, cadmium and lead salts on limb regeneration in the fiddler crab, Uca pugilator. Fish Bull. 1976;74:464–467. [Google Scholar]

- Weis JS, Cristini A, Rao KR. Effects of pollutants on molting and regeneration in Crustacea. Am Zool. 1992;32:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth CK. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J Geol. 1922;30:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener JG, Krabbenhoft DP, Heinz GH, Scheuhammer AM. Ecotoxicology of Mercury. In: Hoffman DJ, Rattner BA, Burton GA Jr, Cairns J Jr, editors. Handbook of ecotoxicology. Lewis Publishers; Boca Raton: 2003. pp. 409–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zotti M, Del Coco L, De Pascali SA, Migoni D, Vizzini S, Mancinelli G, Fanizzi FP. Comparative analysis of the proximate and elemental composition of the blue crab Callinectes sapidus, the warty crab Eriphia verrucosa, and the edible crab Cancer pagurus. Heliyon. 2016;2(2):e00075. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q1, Kim D, Dionysiou DD, Sorial GA, Timberlake D. Sources and remediation for mercury contamination in aquatic systems--a literature review. Environ Pollut. 2004 Sep;131(2):323–36. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]