Abstract

Brucella species are important etiological agents of zoonotic diseases. Attenuated Salmonella strains expressing Brucella abortus BCSP31, Omp3b and superoxide dismutase proteins were tested as vaccine candidates in this study. In order to determine the optimal dose for intraperitoneal (IP) inoculation required to obtain effective protection against brucellosis, mice were immunized with various doses of a mixture of the three vaccine strains. Fifty BALB/c mice were divided into five equal groups (groups A–E). Group A mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with 100 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Group B, C, D and E mice were intraperitoneally immunized with approximately 1.2 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) mL−1 of Salmonella containing pMMP65 in 100 μL and with 1.2 × 104 CFU mL−1, 1.2 × 105 CFU mL−1 and 1.2 × 106 CFU mL−1 of the mixture of the three strains in 100 μL, respectively. Serum IgG, tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma concentrations were significantly higher in group E than in groups A–D. Following challenge with B. abortus 544, the challenge strain was not detected in the spleen of any mouse from group E. Thus, IP immunization with 1.2 × 106 CFU mL−1 of the mixture of the three vaccine strains induced immune responses and provided effective protection against brucellosis in mice.

Keywords: Brucella abortus, brucellosis, immunization, public health, attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium

This report suggests that intraperitoneal immunization with the mixture of the delivery strains can effectively protect mice against brucellosis.

INTRODUCTION

Brucella species are important etiological agents of zoonotic diseases (Avila-Calderon et al.2013; Olsen 2013). Brucellosis is caused by Brucella and leads to abortion in domestic ruminants, thereby making it a major concern. Brucella is a facultative intracellular pathogen, which invades and multiplies intracellularly in macrophages within the host system (Bowden et al.1995; Baldwin and Goenka 2006). Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses can change the course of Brucella infection but cell-mediated immune responses are necessary to clear Brucella from the host organism (Schurig, Sriranganathan and Corbel 2002). In particular, the Th1-type immune response mediated by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) helps to combat Brucella infections (Zhan, Kelso and Cheers 1993). Strong Th2-type humoral immune responses, such as those involving serum IgG, are also necessary for protection against infection with intracellular pathogens (Roesler et al.2006; Brumme et al.2007; Adone et al.2012) because systemic antibodies eliminate pathogens from the blood and promote their phagocytosis by opsonization (Mastroeni et al.2001; Brumme et al.2007). Many vaccines have been designed to combat brucellosis, but the commercially available vaccines comprise live and attenuated Brucella strains. Notably, these strains can revert into pathogenic strains and may also interfere with the diagnosis (Avila-Calderon et al.2013; Olsen 2013). Because of these limita-tions, there is an urgent need for better and safer vaccines.

Live attenuated Salmonella strains have been proposed as a useful vector for carrying protective antigens of other pathogens (Hur and Lee 2011; Hur, Byeon and Lee 2014). The gastrointestinal tract is the entry portal common for both Brucella and Salmonella. Furthermore, most Salmonella vaccine strains retain a limited ability to invade the internal lymphoid organs, and thus, adequate induction of cell-mediated immunity can be expected (Martinoli, Chiavelli and Rescigno 2007).

Recombinant proteins of Brucella abortus may be suitable vaccine candidates because they can never cause infections and the adjuvant or immunization route employed to obtain antigen-specific immune responses can also be modified (Zhao et al.2009). Reportedly, a protein purified from strain 19 designated as the cell surface 31-kDa protein (or BCSP31) can serve as a protective subunit vaccine in rodents (Tabatabai and Deyoe 1983; Tabatabai, Deyoe and Patterson 1989). BCSP31 is either a glycosylated protein or may have a tight association with a Brucella polysaccharide moiety (Bricker et al.1988). Outer membrane proteins (Omps) are the protective antigens of Brucella species (Verstreate et al.1982). Omp3b, also known as Omp22, belongs to group 3 of the Brucella Omps (Vizcaino et al.2004), which is a highly conserved family comprising up to seven members, including some of the most abundant and immunogenic Brucella proteins (Cloeckaert et al.2002). The sodC gene encodes a Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD), which catalyzes the dismutation of oxygen radicals (Bricker et al.1990). SOD might act as a virulence factor by scavenging harmful oxygen radicals produced during phagocytosis by macrophages (Tabatabai and Pugh 1994).

In a previous study (Kim et al.2016), Salmonella Typhimurium strains expressing the BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD proteins of B. abortus were used as vaccine candidates to determine the optimal inoculation route in a murine model. Intraperitoneal (IP) immunization with a mixture of the Salmonella strains induced adequate immune responses and provided effective protection against brucellosis in mice. The present study aimed to determine the optimal dose for IP immunization using a mixture of the Salmonella strains to achieve protection against brucellosis in a murine model. The humoral immune responses and protective efficacy obtained after IP inoculation with various doses of the mixture of three vaccine strains were studied in mice. Mice intraperitoneally inoculated with the Salmonella-based Brucella vaccine candidate exhibited robust humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, thereby yielding effective protection against virulent B. abortus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and ethics statement

Fifty 5-week-old female BALB/c mice were distributed into five equal groups (groups A–E). All mice were maintained according to the previously described method (Hur and Lee 2011). All animal experiments performed in this study received ethical approval (CBU 2015-052) from the Chonbuk National University Animal Ethics Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Korean council on Animal Care.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Attenuated Salmonella vector-mediated strains for delivering the recombinant BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens, which have been constructed and used as vaccine strains in the previous study, were used as vaccine candidates in the present study (Table 1) (Kim et al.2016). Brucella abortus strain 544 (HJL254) was used as the virulent challenge strain (Lee et al.2014). Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) bacteria were used as host cells for overexpressing the recombinant BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens. pET28a and pET32a plasmids were used as vectors for overexpressing the individual antigens. Except for B. abortus strain 544, all strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA) or on LB agar. Brucella abortus strain 544 was grown on Brucella agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA). All strains were cultured at 37°C.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain/plasmid | Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| Escherichia coli | |||

| BL21(DE3) | F–, ompT, hsdSB(rB–,mB–), dcm, gal, λ(DE3) | Lab stock | |

| HJL206 | BL21 with pET32a-BCSP31 | This study | |

| HJL204 | BL21 with pET28a-Omp3b | This study | |

| HJL208 | BL21 with pET28a-SOD | This study | |

| Salmonella Typhimurium | |||

| JOL401 | Salmonella Typhimurium wild type | Lab stock | |

| JOL911 | S. Typhimurium JOL401derivave ΔlonΔcpxR | Lab stock | |

| JOL912 | S. Typhimurium JOL911 derivative Δasd | [20] | |

| HJL229 | JOL912 with pMMP65 | [21] | |

| HJL228 | JOL912 with pMMP65-BCSP31 | [21] | |

| HJL219 | JOL912 with pMMP65-Omp3b | [21] | |

| HJL213 | JOL912 with pMMP65-SOD | [21] | |

| Brucella abortus | |||

| Biotype 1 | B. abortus biotype 1 isolate from cow in Korea | Lab stock | |

| Strain 544 | Brucella abortus strain 544 (ATCC23448) | [20] | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pET28a | IPTG-inducible expression vector; Kmr | Novagen | |

| pET32a | IPTG-inducible expression vector; Ampr | Novagen | |

| pMMP65 | Asd+, pBR ori, β-lactamase signal sequence-based periplasmic secretion plasmid, 6× His tag | [21] | |

Preparation of individual recombinant proteins

The overexpressed recombinant proteins comprising BCSP31 from HJL906, Omp31 from HJL904 and SOD from HJL908 have been conducted and used in a previous study (Kim et al.2016). The recombinant proteins were also used as coating antigens for an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and as re-stimulating proteins for splenocytes in the present study.

Preparation of Salmonella delivery strain formulation

The previously described vaccine candidate strains comprising HJL228, HJL219 and HJL213 were also used as vaccine candidates in the present study (Table 1) (Kim et al.2016).

Immunization of mice and sample collection

Fifty 5-week-old female BALB/c mice were divided into five equal groups (n = 10 mice per group). All mice were immunized at 6 weeks of age. Group A mice were intraperitoneally inoculated with 100 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the control. Group B mice were intraperitoneally immunized with approximately 1.2 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) mL−1 of HJL229 in 100 μL as the vector control. Groups C, D and E mice were intraperitoneally immunized with approximately 1.2 × 104 CFU mL−1, 1.2 × 105 CFU mL−1 and 1.2 × 106 CFU mL−1 of a mixture (equal CFU counts of each strain) of the three delivery strains in 100 μL, respectively. Blood samples were collected before immunization [0 weeks post-immunization (WPI)] and again at 3 WPI to evaluate the serum IgG levels. All samples were stored at −70°C until use.

Immune response measurement by ELISA

Standard ELISA was performed to evaluate the immune responses against the BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens in serum samples obtained from mice according to the previously described method (Kim et al.2016). The ELISA results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Collection of cytokines from splenocytes

At 3 WPI, five mice from each group were sacrificed and their spleens were aseptically removed. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by homogenizing the spleens. Splenocytes were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min. Red blood cells were lysed with 0.9% NH4Cl and then subjected to three washes with complete RPMI medium to remove NH4Cl. Spleen cells were checked for viability using the Trypan blue exclusion method and were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates at 2 × 106 cells per well (Velikovsky et al.2003). Splenocytes were stimulated in vitro using BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens (4 μg well−1), with concanavalin A (0.5 μg well−1) as the positive control or media as the unstimulated control, and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 and 95% humidity (Adone et al.2012). Supernatants were collected from the media after restimulation for 48 h and were stored at −70°C until use for quantifying cytokines (Adone et al.2012).

Measurement of cytokines by ELISA

ELISA was employed to measure the concentrations of cytokines, including IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), in the supernatants using a mouse cytokine ELISA Ready-SET-GO reagent set according to the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Challenge experiments

Strain 544 was prepared for use in the challenge experiments. Briefly, the strain was grown in Brucella broth at 37°C for 24 h and then resuspended to obtain approximately 1 × 105 CFU mL−1. Five mice from each group were intraperitoneally challenged at 3 WPI with 100 μL of the challenge strain. Two weeks after the challenge, spleen weights were measured and the numbers of viable strain 544 cells in the spleens were counted (Kim et al.2016). Vaccine and challenge strains were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the B. abortus-specific primer (5΄-GACGAACGGAATTTTTCCAATCCC-3΄) and IS711-specific primer (5΄-TGCCGATCACTTAAGGGCCTTCAT-3΄) described in previous study (Bricker and Halling 1994, 1995).

Statistical analysis

CFU data were normalized by log transformation and evaluated by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett's post-hoc test using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The cellular responses were compared between the groups using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's Multiple Comparisons test. The analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The antibody responses were compared between the groups using two-way matching by rows (RM) analysis of variance and matching by rows test. The analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Humoral immune responses in the vaccinated mice

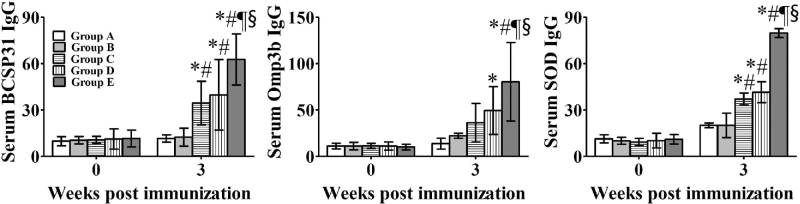

The antibody responses against each antigen in the sera are shown in Fig. 1. Serum IgG concentrations against all antigens were significantly higher in groups D and E than in the control group (P ≤ 0.05). In addition, serum IgG concentrations against the individual antigens were significantly higher in group E than in groups B, C and D (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Antibody responses (ng mL−1) against BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens. Group A mice were inoculated with sterile phosphate-buffered saline as a control. Group B mice were immunized with Salmonella Typhimurium containing pMMP65 only as a vector control. Group C, D and E mice were inoculated with approximately 1.2 × 104 CFU mL−1, 1.2 × 105 CFU mL−1 and 1.2 × 106 CFU mL−1 of the mixture of the three delivery strains in 100 μL, respectively. Data represent the means of all mice in each group, and error bars represent the standard deviations. * P < 0.05 vs Group A; # P < 0.05 vs Group B; ¶ P < 0.05 vs Group C; § P < 0.05 vs Group D.

Cytokine analysis

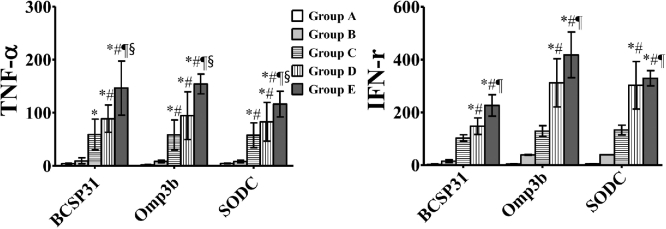

TNF-α and IFN-γ concentrations in splenocytes in response to BCSP31, Omp31 and SOD after re-stimulation with the individual antigens were measured using ELISA at 3 WPI. TNF-α concentrations were significantly higher in groups C, D and E than in groups A and B (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). In addition, compared with group C, TNF-α concentrations in response to all antigens in groups D and E were significantly increased. IFN-γ concentrations in response to all antigens were also significantly higher in groups D and E than in groups A and B. In addition, compared with group C, IFN-γ concentrations in response to all antigens were significantly increased in group E (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Cytokine concentrations (pg mL−1) in splenocytes at 3 WPI. Groups A, B, C, D and E are indicated as in Fig. 1. Data represent the means of all mice in each group, and error bars indicate the standard deviations. * P < 0.05 vs Group A; # P < 0.05 vs Group B; ¶ P < 0.05 vs Group C; § P < 0.05 vs Group D.

Protection of mice against virulent challenge

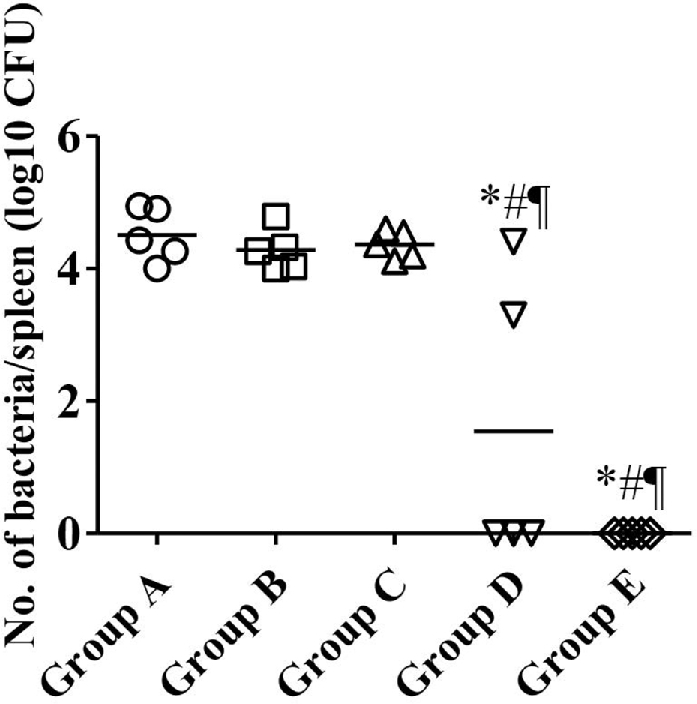

Five mice from each group were intraperitoneally challenged with approximately 4 × 104 CFU of the challenge strain at 3 WPI. Fourteen days after the challenge, the infection level was evaluated by determining the CFU counts in the spleens. As shown in Fig. 3, group D and E mice exhibited significantly greater protection than group A, B and C mice. The challenge strain was isolated from all group A, B and C mice. By contrast, the challenge strain was isolated from only two-fifth of the group D mice and wild-type Brucella abortus was not detected in the spleen of any group E mouse.

Figure 3.

Bacterial proliferation in the spleens of mice challenged with wild-type Brucella abortus strain 544. Groups A, B, C, D and E are indicated as in Fig. 1. All mice in each group were intraperitoneally challenged with 1 × 104 CFU of virulent wild-type B. abortus 544 at 3 WPI. The numbers of viable bacteria recovered from the spleens of mice on day 14 post-challenge are shown. The lines represent the means (n = 5 mice per group). * P < 0.05 vs Group A; # P < 0.05 vs Group B; ¶ P < 0.05 vs Group C; § P < 0.05 vs Group D.

DISCUSSION

Brucellosis is a globally distributed zoonotic disease, which causes severe detrimental effects to health and economic losses in endemic areas (Carvalho Neta et al.2010). Brucella abortus is a facultative intracellular bacterium that can invade hosts through the mucosa and survive inside phagocytes by evading the endocytic pathway. The gastrointestinal tract is one of the major entry portals for B. abortus (Gorvel, Moreno and Moriyon 2009). The resistance of hosts to Brucella infection mainly depends on mucosal immunity and acquired cell-mediated immunity. The two main components of the host protective systemic immune responses are CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD8+ T lymphocytes secreting IFN-γ and the lysis of Brucella-infected cells (Paranavitana et al.2005).

Attenuated Salmonella has many advantages as a vector for carrying protective Brucella antigens; these include the delivery of the antigen to the host, a simple preparation procedure and convenient inoculation (Chen and Schifferli 2003; Hur, Byeon and Lee 2014). In the present study, attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium host cells and the pMMP65 plasmid delivery system were used to deliver B. abortus BCSP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens, as described in a previous study (Kim et al.2016). Mice were immunized with three different doses of a mixture of the Salmonella-based Brucella vaccine candidates. Compared with control group mice, group D (immunized with approximately 1 × 105 CFU) and E (immunized with approximately 1 × 106 CFU) mice produced significantly higher amounts of serum IgG in response to the three antigens. In addition, serum IgG concentrations in group E were significantly higher than those in groups B (immunized with the Salmonella containing vector only), C (immunized with approximately 1 × 104 CFU) and D (immunized with approximately 1 × 105 CFU). However, serum IgG concentrations in group B were only slightly higher than those in the control group. Thus, IP immunization with approximately 1.0 × 106 CFU significantly induced a protective IgG response.

The Th1-type immune response is considered to be desirable for protection against brucellosis (Zhan, Liu and Cheers 1996; Baldwin and Goenka 2006). The role of TNF-α in controlling Brucella infection in mice is important because of the activation of macrophages, which are responsible for killing Brucella in the absence of IFN-γ (Zhan, Liu and Cheers 1996). IFN-γ plays a crucial role in combating Brucella infection because of its ability to activate the antibacterial functions of infected macrophages (Paranavitana et al.2005; Baldwin and Goenka 2006). In this study, we investigated the cell-mediated immune response generated by IP immunization with Salmonella vaccine candidates expressing B. abortus BSCP31, Omp3b and SOD antigens. Cytokine concentrations were evaluated in the supernatants obtained from the splenocytes of mice immunized with the vaccine candidates after re-stimulation with the heat-inactivated B. abortus whole antigens. TNF-α and IFN-γ concentrations were significantly higher in groups D and E than in groups A (immunization with PBS) and B (immunization with Salmonella containing pBP244 only). These results indicated that IP immunization with approximately 1 × 105 CFU of the mixture of Salmonella vaccine candidates could induce strong Th1-type immune responses. Furthermore, significantly higher IFN-γ and TNF-α concentrations were found in the culture supernatants of splenocytes obtained from group E mice than in those obtained from group C. Thus, it is logical to conclude that IFN-γ produced by IP immunization with approximately 1 × 106 CFU of the mixture might have contributed to the increased protection in this group.

A major difficulty that has prevented the development of a vaccine against Brucella is the lack of the definite proof of efficient protection. We found that group C, D and E mice exhibited significantly greater protection than group A and B mice, demonstrating that IP immunization with the Salmonella vaccine candidates could protect mice from infection with the virulent B. abortus strain 544. Furthermore, group E mice exhibited the best protection against infection with the virulent B. abortus strain 544. It is possible that IP immunization with approximately 1 × 106 CFU of the Salmonella mixture made larger amounts of antigens available to antigen-presenting cells, which induced the strongest mucosal and cell-mediated immune responses.

In summary, the results of this study demonstrated that IP immunization with approximately 1 × 106 CFU of Salmonella-based Brucella vaccine induced robust antibody and cell-mediated immune responses in mice. The vaccine conferred protection against infection with B. abortus, which was comparable to that by immunization with approximately 1 × 106 CFU of the Salmonella-based Brucella vaccine. Thus, we suggest that IP immunization with approximately 1 × 106 CFU of the Salmonella mixture is a good candidate for vaccine development to combat brucellosis.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MISP) (No. 2013R1A4A1069486).

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Adone R, Francia M, Pistoia C et al. Protective role of antibodies induced by Brucella melitensis B115 against B. melitensis and Brucella abortus infections in mice. Vaccine 2012;30:3992–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Calderon ED, Lopez-Merino A, Sriranganathan N et al. A history of the development of Brucella vaccines. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:743509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CL, Goenka R. Host immune responses to the intracellular bacteria Brucella: does the bacteria instruct the host to facilitate chronic infection? Crit Rev Immunol 2006;26:407–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden RA, Cloeckaert A, Zygmunt MS et al. Surface exposure of outer membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide epitopes in Brucella species studied by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and flow cytometry. Infect Immun 1995;63:3945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker B, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:2660–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker B, Halling SM. Enhancement of the Brucella AMOS PCR assay for differentiation of Brucella abortus vaccine strains S19 and RB51. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:1640–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker BJ, Tabatabai LB, Deyoe BL et al. Conservation of antigenicity in a 31-kDa Brucella protein. Vet Microbiol 1988;18:313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker BJ, Tabatabai LB, Judge BA et al. Cloning, expression, and occurrence of the Brucella Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. Infect Immun 1990;58:2935–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumme S, Arnold T, Sigmarsson H et al. Impact of Salmonella Typhimurium DT104 virulence factors invC and sseD on the onset, clinical course, colonization patterns and immune response of porcine salmonellosis. Vet Microbiol 2007;124:274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho Neta AV, Mol JP, Xavier MN et al. Pathogenesis of bovine brucellosis. Vet J 2010;184:146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Schifferli DM. Construction, characterization, and immunogenicity of an attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium pgtE vaccine expressing fimbriae with integrated viral epitopes from the spiC promoter. Infect Immun 2003;71:4664–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloeckaert A, Vizcaino N, Paquet JY et al. Major outer membrane proteins of Brucella spp.: past, present and future. Vet Microbiol 2002;90:229–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvel JP, Moreno E, Moriyon I. Is Brucella an enteric pathogen? Nat Rev Microbiol 2009;7:250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J, Byeon H, Lee JH. Immunologic study and optimization of Salmonella delivery strains expressing adhesin and toxin antigens for protection against progressive atrophic rhinitis in a murine model. Can J Vet Res 2014;78:297–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J, Lee JH. Immune responses to new vaccine candidates constructed by a live attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium delivery system expressing Escherichia coli F4, F5, F6, F41 and intimin adhesin antigens in a murine model. J Vet Med Sci 2011;73:1265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WW, Moon JY, Kim S et al. Comparison between immunization routes of live attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium strain expressing BCSP31, Omp3b, and SOD of Brucella abortus in murine model. Fron Microbiol 2016;7:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Lim JJ, Kim DG et al. Characterization of culture supernatant proteins from Brucella abortus and its protection effects against murine brucellosis. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2014;37:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinoli C, Chiavelli A, Rescigno M. Entry route of Salmonella typhimurium directs the type of induced immune response. Immunity 2007;27:975–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni P, Chabalgoity JA, Dunstan SJ et al. Salmonella: immune responses and vaccines. Vet J 2001;161:132–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SC. Recent developments in livestock and wildlife brucellosis vaccination. Rev Sci Tech 2013;32:207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranavitana C, Zelazowska E, Izadjoo M et al. Interferon-gamma associated cytokines and chemokines produced by spleen cells from Brucella-immune mice. Cytokine 2005;30:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesler U, Heller P, Waldmann KH et al. Immunization of sows in an integrated pig-breeding herd using a homologous inactivated Salmonella vaccine decreases the prevalence of Salmonella typhimurium infection in the offspring. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 2006;53:224–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurig GG, Sriranganathan N, Corbel MJ. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. Vet Microbiol 2002;90:479–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabai LB, Deyoe BL, Patterson JM. Immunogenicity of Brucella abortus salt-extractable proteins. Vet Microbiol 1989;20:49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabai LB, Deyoe BL. Isolation of two biologically active cell surface proteins from Brucella abortus by chromatofocusing. Fed Proc 1983;42:2127 [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabai LB, Pugh GW Jr. Modulation of immune responses in Balb/c mice vaccinated with Brucella abortus Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase synthetic peptide vaccine. Vaccine 1994;12:919–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikovsky CA, Goldbaum FA, Cassataro J et al. Brucella lumazine synthase elicits a mixed Th1-Th2 immune response and reduces infection in mice challenged with Brucella abortus 544 independently of the adjuvant formulation used. Infect Immun 2003;71:5750–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreate DR, Creasy MT, Caveney NT et al. Outer membrane proteins of Brucella abortus: isolation and characterization. Infect Immun 1982;35:979–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino N, Caro-Hernandez P, Cloeckaert A et al. DNA polymorphism in the omp25/omp31 family of Brucella spp.: identification of a 1.7-kb inversion in Brucella cetacea and of a 15.1-kb genomic island, absent from Brucella ovis, related to the synthesis of smooth lipopolysaccharide. Microbes Infect 2004;6:821–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Kelso A, Cheers C. Cytokine production in the murine response to Brucella infection or immunization with antigenic extracts. Immunology 1993;80:458–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Liu Z, Cheers C. Tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-12 contribute to resistance to the intracellular bacterium Brucella abortus by different mechanisms. Infect Immun 1996;64:2782–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Li M, Luo D et al. Protection of mice from Brucella infection by immunization with attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium expressing A L7/L12 and BLS fusion antigen of Brucella. Vaccine 2009;27:5214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]