Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a novel therapeutic option for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) at excessive or high surgical risk for conventional surgical aortic valve replacement. First commercialised in Europe in 2007, TAVI growth has been exponential among some Western European nations, though recent evidence suggests heterogeneous adoption of this new and expensive therapy. Herein, we review the evidence describing the utilisation of TAVI in Western Europe.

Keywords: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation, aortic stenosis

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a safe and efficacious treatment in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) at high- or excessive-risk for surgical aortic valve replacement.[1,2] More recently, TAVI technology has been extended to treating high-risk patients with failing aortic or mitral surgical bioprosthetic valves, bicuspid aortic stenosis, pure aortic regurgitation, and lower-risk aortic stenosis patients.[3–8] Thus, TAVI technology is increasingly being applied worldwide since Conformité Européenne mark approval of the Edwards SAPIEN (Edwards Lifesciences Inc, Irvine, California, US) and Medtronic CoreValve (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, US) systems in 2007.

Importantly, few studies report the adoption of TAVI across nations. Anecdotal evidence of TAVI practice in Europe, and studies describing the adoption of other novel medical devices, such as drug-eluting stents (DES) and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), suggest that the use of expensive new technologies may be inconsistent across nations.[9,10] Indeed, such is the inequality in the adoption of DES and ICD technology that societal initiatives have been established in an attempt to level the playing field between nations.[11]

Herein, we profile the adoption of TAVI in Western Europe, highlight some factors that may account for the disparate adoption of TAVI between nations, and present evidence that suggests that this therapy remains greatly underutilised in Europe.

Adoption of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation

We evaluated TAVI adoption among 11 Western European Nations – Germany, France, Italy, UK (including Northern Ireland), Spain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Portugal, Denmark and the Republic of Ireland.[12] The number of TAVI implants and TAVI centres in each nation were retrieved from national databases that were submitted by a selected group of investigators. These data were cross-referenced with TAVI use estimates derived by BIBA MedTech (London, UK), a cardiovascular market analysis group.

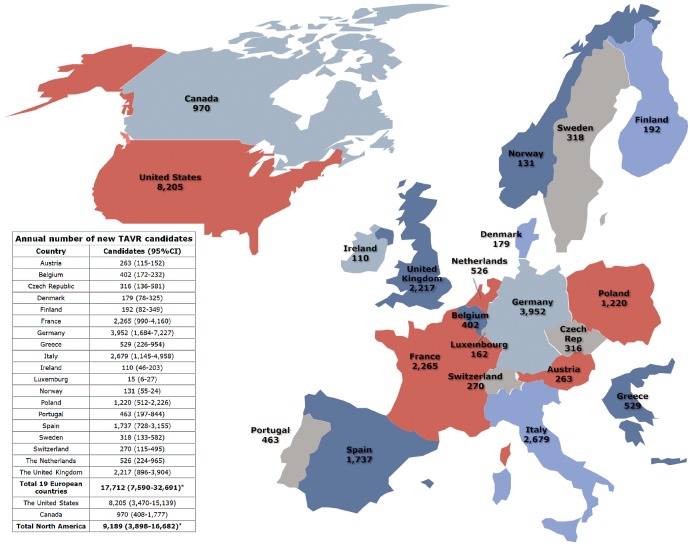

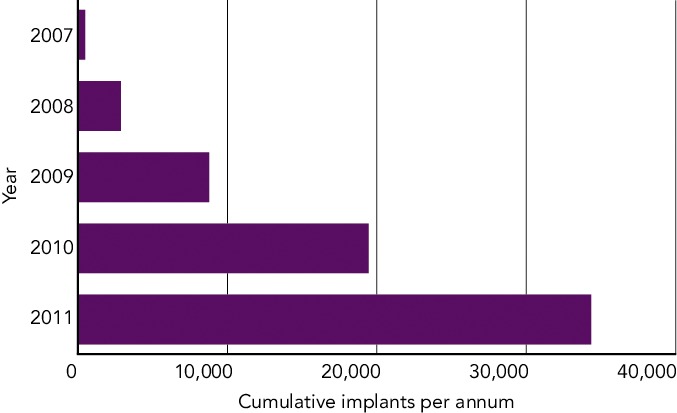

Between 2007 and 2011, 34,317 patients underwent TAVI in the 11 study nations. TAVI implants increased 33-fold from 445 in 2007 to 14,946 in 2011 (see Figure 1). Most implants were performed in Germany (45.9 %), Italy (14.9 %) and France (12.9 %) (see Figure 2). Portugal (0.6 %) and Ireland (0.4 %) accounted for the smallest proportion of implants.

Figure 1: Cumulative European Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Implants (2007–2011).

Total number of TAVI implants among 11 European nations from 2007 to 2011.

Figure 2: Nation Specific Cumulative Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implants (2007–2011).

Total number of TAVI implants in each study nation from 2007 to 2011. TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

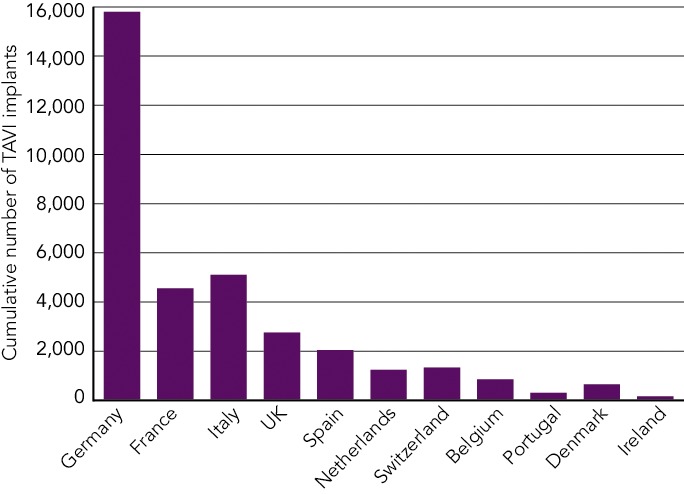

When the cumulative TAVI implant numbers were applied to year-end national population estimates, we observed considerable disparity in TAVI utilisation among nations (see Figure 3). In 2011, Germany (961), Switzerland (797) and Denmark (611) had the highest TAVI implant rates per million of population ≥75 years of age. Portugal (71) and Ireland (127) had the lowest TAVI implant rates.

Figure 3: Variability in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Utilisation.

Transcatheter aortic valve implant rates per million of population ≥75 years of age in 2011 among 11 European nations. TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Centres

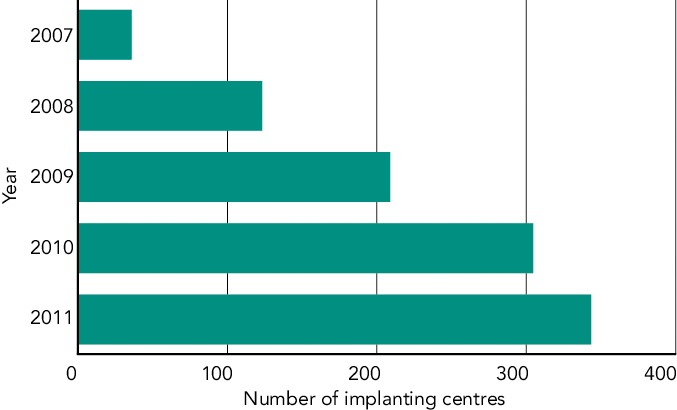

The number of TAVI centres increased ninefold from 37 in 2007 to 342 in 2011 (see Figure 4). On average, there were 0.9 ± 0.6 TAVI centres per million of population. In 2011, the number of TAVI centres ranged from 0.3 per million in Portugal to 2.1 per million in Belgium. A high number of TAVI centres per million of population can result in fewer procedures being performed in each centre. Hence, guidelines recommend that TAVI procedures be centralised in high-volume regional centres to ensure adequate operator and centre experience.[13,14] These volume-based recommendations suggest that a minimum of 24 TAVI procedures be performed in each centre per annum.[13,14] Despite a European average of 41 ± 28 TAVI implants per centre in 2011, Ireland, Belgium and Spain all had TAVI centres that performed <20 TAVI implants annually. The low number of implants per centre may be explained by the low procedural volume in Ireland and by a high number of TAVI centres in Belgium and Spain. National administration and funding agencies should be encouraged to centralise TAVI in designated TAVI centres and ensure that the recommended minimal implant volume is achieved.

Figure 4: Number of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Centres in Europe.

Total number of centres performing transcatheter aortic valve implantation in 11 European nations from 2007 to 2011.

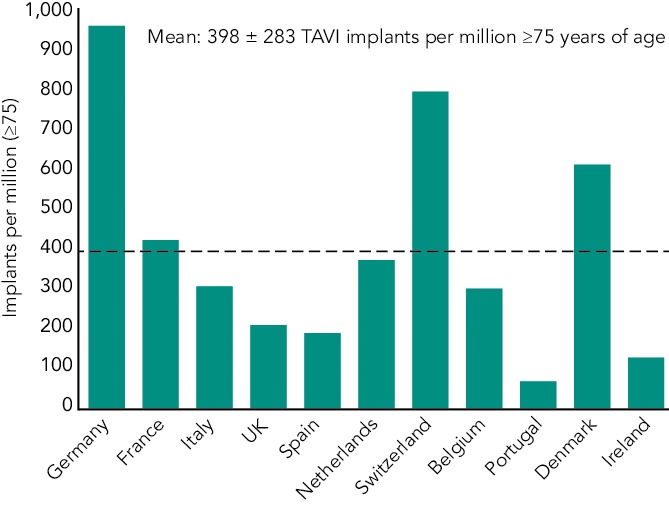

Number of Potential Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Candidates

Recently, Osnabrugge et al. evaluated the potential number of TAVI candidates in 19 European nations and in North America.[15] These authors estimated the prevalence of severe aortic stenosis in the elderly (≥75 years) to be 3.4 % (95 % confidence interval [CI], 1.1–5.7 %). To calculate the number of potential TAVI candidates in each nation, a meta-analysis was performed, which focused on published data describing the treatment pathway of high-risk aortic stenosis patients. It was estimated that 75.6 % of patients with severe aortic stenosis were symptomatic, 40.5 % were inoperable due to excessive surgical risk, and among patients that undergo surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), 5.2 % were at high operative risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk of mortality >10 %). Finally, 40.3 % of inoperable patients and 80.0% of high-risk patients were deemed to be potential TAVI candidates.

Extrapolating these data, Osnabrugge et al. estimated that there are 189,836 (95 % CI, 80,281–347,372) TAVI candidates in the Europe and 102,558 (95 % CI, 43,612–187,002) in North America. Annually, there are 17,712 (95 % CI, 7,590–32,691) new TAVI candidates in Europe and 9,189 (95 % CI, 3,898–16,682) in North America (see Figure 5). Like all meta-analyses and modelling studies, this study has limitations, such as differences in the definition of aortic stenosis used among the included studies and more importantly, the difficulty associated with determining the number of inoperable or high-risk patients that are truly suitable for TAVI.[16] In the future, more comprehensive prospective national and international registries detailing the actual treatment of high-risk aortic stenosis patients (medical therapy, SAVR, TAVI) will provide invaluable insights into the management of aortic stenosis patients. In the meantime, the study by Osnabrugge et al. reflects the best available evidence detailing the prevalence of severe aortic stenosis in the elderly, and provides the only estimate of the number of potential of TAVI candidates.

Figure 5: Annual Number of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Candidates Under the Current Treatment Indications.

Annual number of transcatheter aortic valve implantation candidates in different countries under the current treatment indications. CI = confidence interval; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Reprinted with permission from Osnabrugge, et al., 2013.[15]

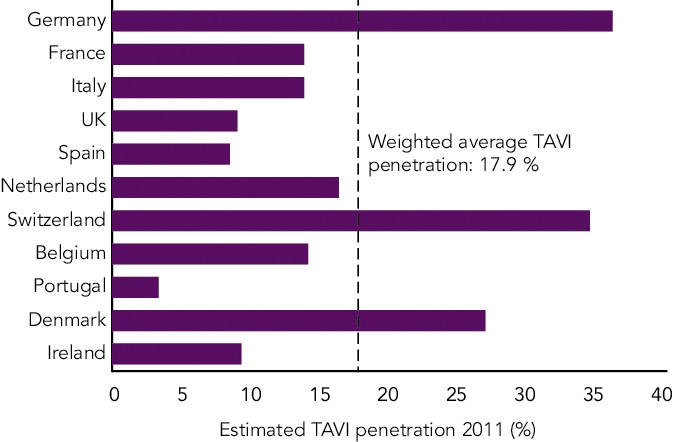

Estimated Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Penetration

The penetration of a therapy describes actual use relative to potential use. Applying the 2011 TAVI implant data to the number of potential TAVI candidates, one can approximate the penetration of TAVI in each nation (see Figure 6). In Germany, the estimated TAVI penetration rate was 36.2 %; that is, 36.2 % of TAVI eligible patients went on to receive TAVI in 2011. This contrasts considerably with the estimated penetration rate in Portugal (6.4 %). The weighted average TAVI penetration was calculated according to the weight (number of TAVI cases performed) or relative contribution of each individual nation to the average). Overall, the weighted average penetration rate for the 11 European nations was only 17.9 %.

Figure 6: Estimated European Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Penetration 2011.

Estimated transcatheter aortic valve implantation penetration among 11 European nations in 2011. TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

It is important to note that the denominator for estimating TAVI penetration is based on the number of potential TAVI candidates described by Osnabrugge et al. As such, the TAVI penetration calculation is subject to the limitations of this study. As noted by Webb et al., a more conservative estimation of the number of potential TAVI candidates would have altered the penetration calculation significantly.[17] For example, a commercial analysis of the US TAVI market has suggested that TAVI penetration is already at approximately 45 %, despite the delayed and highly restrictive introduction of TAVI in that country.[18]

With ongoing trials in intermediate-risk patients, it is generally expected that TAVI use will continue to rise worldwide. Device iteration, documentation of long-term efficacy, and reduced costs will drive the adoption of this therapy. Furthermore, as patient selection and procedural outcomes improve, the currently underappreciated morbidity and mortality advantages of TAVI are likely to become apparent, and it is likely that TAVI utilisation will increase further.

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Funding and Reimbursement Issues

Given the prevalence of aortic stenosis in the elderly, the ageing global population, and the absence of effective preventative therapies, the economic burden of aortic stenosis is increasing. Of course, the adoption of TAVI is affected by economic conditions: more prosperous nations that spend more on healthcare tend to perform more TAVIs.[12] Implant rates are also affected by reimbursement strategies – nations with TAVI-specific diagnosis-related groups that cover all of the costs of TAVI tend to perform more TAVI than nations where the cost of TAVI is reimbursed and constrained at local level.[12] Importantly, these differences in reimbursement may also have the potential to impact patient outcomes; as in nations with more constrained local reimbursement, less experience with the procedure is developed.

Conclusions

There are a large number of potential TAVI candidates in Western Europe and the concomitant economic burden is considerable. Adoption of TAVI in Europe is heterogeneous and varies according to nation-specific economic situations, healthcare policies and reimbursement strategies. Current evidence suggests that TAVI remains underutilised in Europe.

References

- 1.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dvir D, Webb J, Brecker S et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement for degenerative bioprosthetic surgical valves: results from the global valve-in-valve registry. Circulation. 2012;126(19):2335–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mylotte D, Lange R, Martucci G, Piazza N. Transcatheter heart valve implantation for failing surgical bioprostheses: technical considerations and evidence for valve-in-valve procedures. Heart. 2013;99(13):960–7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashida K, Bouvier E, Lefèvre T et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for patients with severe bicuspid aortic valve stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(3):284–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange R, Bleiziffer S, Mazzitelli D et al. Improvements in transcatheter aortic valve implantation outcomes in lower surgical risk patients: a glimpse into the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenaweser P, Stortecky S, Schwander S et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with estimated low or intermediate surgical risk undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(25):1894–905. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy DA, Schaefer U, Guetta V et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for pure severe native aortic valve regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(15):1577–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubinski A, Bissinger A, Boersma L et al. Determinants of geographic variations in implantation of cardiac defibrillators in the European Society of Cardiology member countries--data from the European Heart Rhythm Association White Book. Europace. 2011;13(5):654–62. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramcharitar S, Hochadel M, Gaster AL et al. An insight into the current use of drug eluting stents in acute and elective percutaneous coronary interventions in Europe. A report on the EuroPCI Survey. EuroIntervention. 2008;3(4):429–41. doi: 10.4244/a78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristensen SD, Fajadet J, Di Mario C et al. Implementation of primary angioplasty in Europe: stent for life initiative progress report. EuroIntervention. 2012;8(1):35–42. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I1A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mylotte D, Osnabrugge RL, Windecker S et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in Europe: adoption trends and factors influencing device utilization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(3):210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Al-Attar N et al. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2008;29(11):1463–70. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tommaso CL, Bolman RM 3rd, Feldman T et al. Multisociety (AATS, ACCF, SCAI, and STS) expert consensus statement: operator and institutional requirements for transcatheter valve repair and replacement, part 1: transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(22):2028–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osnabrugge RL, Mylotte D, Head SJ et al. Aortic stenosis in the elderly: disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):1002–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahanian A, Iung B, Himbert D. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a treatment we are going to need! J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):1013–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb JG, Barbanti M. Transcatheter aortic valve adoption rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(3):220–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan J.P. Edwards Lifesciences, The US TAVR Market: What We Learned from this Weekend’s Publication. North American Equity Research. 2013. ftp://115.113.198.66/DOC%20&%20IR/2013/DECEMBER/13%20DEC/SWETA_EW/20131118_EW_HQ_1.PDF. ftp://115.113.198.66/DOC%20&%20IR/2013/DECEMBER/13%20DEC/SWETA_EW/20131118_EW_HQ_1.PDF Available at: (accesssed 21 February 2014)