Abstract

The bacterial flagellar motor is a self-assembling supramolecular nanodevice. Its spontaneous biosynthesis is initiated by the insertion of the MS ring protein FliF into the inner membrane, followed by attachment of the switch protein FliG. Assembly of this multiprotein complex is tightly regulated to avoid nonspecific aggregation, but the molecular mechanisms governing flagellar assembly are unclear. Here, we present the crystal structure of the cytoplasmic domain of FliF complexed with the N-terminal domain of FliG (FliFC–FliGN) from the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. Within this complex, FliFC interacted with FliGN through extensive hydrophobic contacts similar to those observed in the FliFC–FliGN structure from the thermophile Thermotoga maritima, indicating conservation of the FliFC–FliGN interaction across bacterial species. Analysis of the crystal lattice revealed that the heterodimeric complex packs as a linear superhelix via stacking of the armadillo repeat–like motifs (ARM) of FliGN. Notably, this linear helix was similar to that observed for the assembly of the FliG middle domain. We validated the in vivo relevance of the FliGN stacking by complementation studies in Escherichia coli. Furthermore, structural comparison with apo FliG from the thermophile Aquifex aeolicus indicated that FliF regulates the conformational transition of FliG and exposes the complementary ARM-like motifs of FliGN, containing conserved hydrophobic residues. FliF apparently both provides a template for FliG polymerization and spatiotemporally controls subunit interactions within FliG. Our findings reveal that a small protein fold can serve as a versatile building block to assemble into a multiprotein machinery of distinct shapes for specific functions.

Keywords: conformational change, Helicobacter pylori, molecular motor, protein assembly, protein structure, flagellar motor, bacterial motility

Introduction

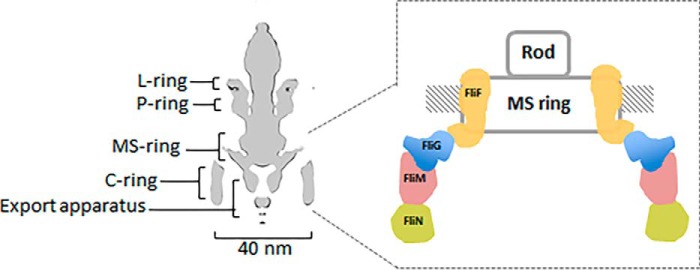

The bacterial flagellar motor is a self-assembled reversible rotary nanodevice. This dynamic rotary motor of ∼40 nm in diameter is composed of rings of protein oligomers: the L ring (outer membrane), P ring (peptidoglycan layer), MS ring (inner membrane), and C ring (cytoplasm) (1, 2). The L and P rings are believed to act as a bushing through which a central rotating rod can pass. The MS and C rings contribute to the rotor part of the flagellar motor. Torque is generated by a membrane-bound stator, which converts electrochemical potential into mechanical force that acts on the rotor. The synthesis of the flagellum begins at the rotor, which is composed of the MS and C ring protein subassemblies (Fig. 1). Specifically, the assembly of the MS ring protein FliF prompts the incorporation of the switch protein FliG and subsequently the proteins FliM and FliN to form the cytoplasmic motor switch complex. The MS ring plays an important role as it interacts both with the rod where the flagellum is anchored and with the C ring where torque generation and rotation switching take place.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a bacterial flagellar motor. Left, cross section of the flagellar motor from Salmonella (2). The four ring oligomers are indicated. Right, enlarged image showing the arrangement of FliF, FliG, FliM, and FliN in the MS and C rings.

In Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli, there are ∼26 copies of FliF in the MS ring and 26 copies of FliG, 34 copies of FliM, and more than 100 copies of FliN in the C ring (3). Many biochemical studies have shown that the junction of the MS and C rings arises from the 1:1 stoichiometric interaction between the C-terminal 40-residue-long cytoplasmic region of FliF (FliFC) and the N-terminal domain of FliG (FliGN) (4–11). The characterization of spontaneous FliF–FliG deletion-fusion mutants in Salmonella and other mutagenesis studies has further shown that gene interruption of FliFC and FliGN cause a defect in flagellation and motility (4–6, 12), which strongly suggests that the optimal function of flagella requires the interaction and conformational freedom of FliFC and FliGN. Although tremendous effort has been spent on understanding the FliG structure in switch assembly, torque generation, and rotational switching, the atomic details of the initial phase of the MS–C ring complex formation remain poorly understood. The crystal structures of FliG from various bacterial species have been determined (13–15). FliG is comprised of three domains: FliGN, FliGM, and FliGC, where the subscripts denote the N-terminal, middle, and C-terminal domains, respectively. Each domain contains an armadillo (ARM)4 repeat motif (ARMN, ARMM, and ARMC). The structures of FliG reveal that the ARMM and ARMC mediate the intersubunit interactions of FliG to form the outer C ring. However, the molecular details of the assembly of FliG and FliF in the inner ring are also poorly understood. Currently, the information about FliGN is only available from the homologs of the thermophile Aquifex aeolicus and Thermotoga maritima (10, 13), and the corresponding structure in human pathogen–related mesophilic bacteria remains unresolved. Notably, the structural model of the FliGN ring generated from the crystal structure of FliF–FliG from T. maritima did not reconcile with the E. coli model derived from the biochemical studies (10, 11). During our previous efforts to solve the structure of FliGMC from Helicobacter pylori, a human pathogenic bacterium related to gastric cancer, we noticed that although the middle and C-terminal domains of H. pylori FliG shared a relatively high sequence identity with their thermophilic counterparts, the N-terminal domain of FliGN was less conserved (∼18 and 30% sequence identity with that from A. aeolicus and T. maritima, respectively). Our goal was to clarify the structure of FliGN in H. pylori to better understand the common and diverse mechanism governing the flagellar assembly among different bacteria. We performed a structural analysis of the FliFC–FliGN complex from H. pylori. Our structure of FliFC–FliGN complex revealed how the two proteins assembled with strong affinity for the attachment of the C ring and how FliFC triggered the conformational change of FliGN to initiate the macromolecular assembly through stacking of the FliGNARM motifs.

Results and discussion

The crystal structure of FliF–FliG from H. pylori

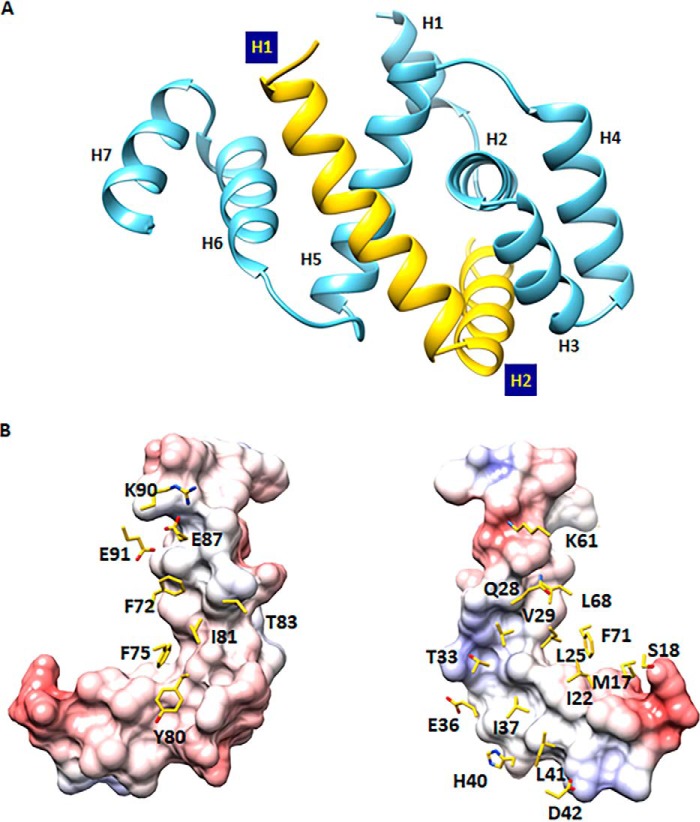

To understand the molecular architecture of the MS–C ring complex, we solved the crystal structure of the FliFC–FliGN binary complex from H. pylori at a resolution of 2.3 Å. The complex consisted of FliF residues 523–559 and FliG residues 7–111 and was entirely α-helical and well packed (Fig. 2A). The electron density map was clearly defined throughout the structure, except for the region comprised of the first 40 residues in the expression construct of FliFC. Because trypsin was added in the crystallization experiment, it is possible that this 40-residue fragment was cleaved by the protease. To validate this, purified FliFC–FliFN complex was subjected to trypsin-limited proteolysis, and the trypsinized FliF fragment was subjected to Western blot and mass spectrometry analyses (Fig. S1). Our results showed that residues 484–510 were cleaved. Previous work in T. maritima (9, 10) has demonstrated that residues 495–532 of FliF (equivalent to residues 523–560 of H. pylori FliF) are essential for wildtype motility and FliG association. It is likely that residues 511–522 of FliF missing in our structural model are not involved in FliG interaction and therefore are likely disordered. The remaining 37-residue polypeptides in FliFC were folded into two α-helices. The first helix started at residue 524 and ended at residue 544, and another helix started at residue 545 and ended at residue 559. The highly conserved Pro545 generated a kink between the two helices, which adopted a near perpendicular orientation (Fig. S2A). The N-terminal domain of FliG was composed of seven helices. The first helix consisted of residues 7–15 with low amino acid conservation, and this region appeared to occur in some bacterial species only (Fig. S2B). Helices 2–4 constituted the ARMN, within which the highly conserved hydrophobic patch previously reported to be critical for FliF binding was localized to helices 2–3 (9). Helix 5 crossed over helix 2 and was located opposite from helices 3–4. The last two helices from residues 84–98 and residues 99–111 connected to the N-terminal and middle domains of FliG. A conserved glycine at the beginning of helix 6 (equivalent to helix 5 in A. aeolicus FliG) was thought to coordinate the orientation of the two FliG domains during motor assembly and rotation. We have also mapped a shorter FliGN containing residues 1–99 to be the minimal region required for FliF–FliG interaction (data not shown). However, no crystals were obtained. When expressed alone, this shorter FliG was much less soluble, suggesting that the presence of helices 6–7 helped stabilize the FliG structure.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of the FliFC–FliGN binary complex. A, graphic representation of the FliFC–FliGN complex with FliFC colored in yellow and FliGN colored in blue. B, the binding interface between FliFC and FliGN. FliFC is presented as a molecular surface colored by an electrostatic potential gradient, and residues of FliGN on the interface are presented as sticks.

The crystal structure of H. pylori FliFC–FliGN complex was solved by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) phasing using a selenomethionine-labeled crystal. We initially attempted molecular replacement with A. aeolicus FliG as a template model, but no solution could be found, indicating that the two FliGN structures were different. Interestingly, the top hit (z-score 7.4) from a search for structural homology using the Dali server (16) revealed the ARM motif of the FliG middle domain from A. aeolicus (13) and H. pylori (15). The structural alignment of helices 2–5 from H. pylori FliGN with the ARMM gave a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) Cα of 1.9 Å for (A. aeolicus) and 2.1 Å for (H. pylori) (Fig. S3).

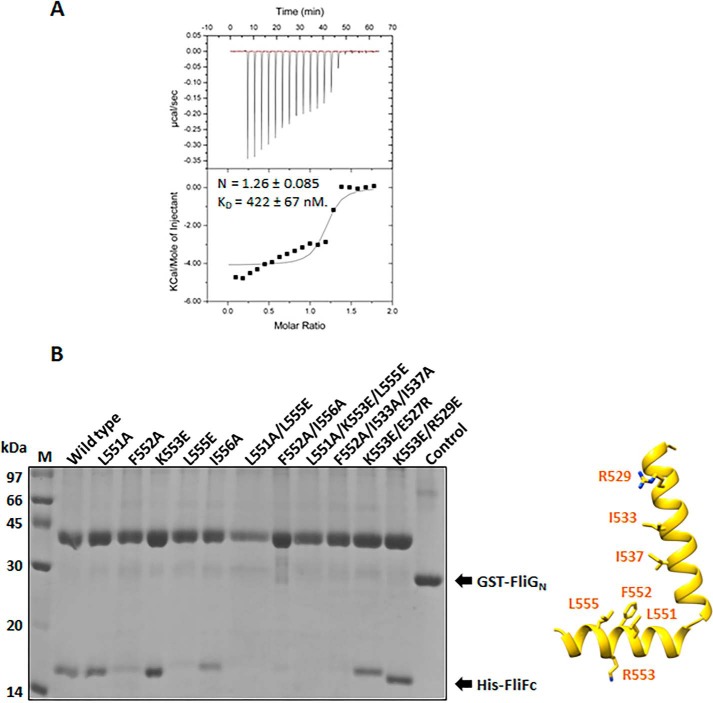

The structure of the FliFC–FliGN binary complex showed a 1:1 stoichiometry ratio, in agreement with the results from static light scattering (Fig. S4) and previous findings (8–11). The two helices of the FliF clipped to the central cleft created by helices 2–5 of FliG, giving an extensive interface area of 1461 Å2 on FliF and 1347 Å2 on FliG (Fig. 2B). The interface was comprised of 22 residues on FliF and 27 residues on FliG, a total of 4 salt bridges, 9 hydrogen bonds, and 109 nonbonded contacts, resulting in a strong affinity site (KD = 0.4 μm) (Fig. 3A). The main contact was within the highly conserved hydrophobic residues near the kink of the two helices in FliF and helices 2 and 5 in FliG (Fig. 2B). We validated some of these interactions with mutagenesis and a pulldown assay using GST-FliGN (Fig. 3B). Our results showed that the FliFC–FliGN interaction was significantly weakened in FliF mutants L552A and L555E. Further interruption of the hydrophobic residues on helices 1 and 2 of FliF nearly abolished the FliG-binding, as shown by the L551A/L555E and F552A/I556A double mutants and the F552A/I533A/I537A triple mutant. These findings suggest that the highly conserved Leu551, Phe552, Leu555, and Ile556 positioned in the middle of helix 2 of FliF were critical. The interruption of the two salt bridges, Arg529FliF:Glu87FliG and Lys553FliF:Asp42FliG, did not have any effect on the heterodimer formation, suggesting that the hydrophobic contacts were the dominant contributors to the stable interaction of FliF and FliG. These results agree with earlier mutagenesis studies in E. coli and Salmonella and with the structure of T. maritima FliF–FliG (4, 6, 10–12).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the FliF–FliG interaction from H. pylori. A, isothermal calorimetric titration (ITC) of FliGN with FliFC. The ITC experiment was performed by titrating 480 μm FliFC into 50 μm FliGN. The data were analyzed and the thermodynamic parameters were obtained using Origin software. The heats were integrated and fit into a single binding site model. Values are expressed as mean ± S.D. and were calculated from three independent experiments: n = 1.26 ± 0.085, KD = 422 ± 67 nm. B, the molecular interaction of FliFC–FliGN using a pulldown assay. Different His-tagged FliF variants were individually co-expressed with GST-tagged FliGN in E. coli. The clear cell lysate was immobilized on the glutathione Sepharose. After washing, the formation of the FliFC–FliGN complex was examined by SDS-PAGE. The control experiment using GST co-expressed with FliF was set. The location of the mutation sites on FliF are indicated by sticks in the structure (left).

Flagellar formation and full motility required hydrophobic contacts between FliF and FliG

Because our structure represented the first atomic model of the FliF–FliG complex from mesophilic bacteria, we completed an in vivo complementation study in an E. coli system to confirm the importance of the hydrophobic contacts between FliFC and FliGN in flagellar motor assembly and function. Various FliG constructs were created: F59D, F66D, and F59D/F66D. After transformation into the fliG-null strain, the effects of these mutations on flagellar formation and bacterial motility were examined with a transmission electron microscope and soft agar assays, respectively. We hypothesized that substitution of these two residues with aspartate in helix 5 of FliG would disrupt FliF-binding and therefore flagellar formation. As shown in Fig. 4A, the percentage of flagellated cells in the F59D mutant strain was reduced to 44% (40 of 91 cells) compared with the wildtype complemented strain. A more severe defect in flagellation was observed in the F59D/F66D double mutant strain (30 of 90 cells). These results agree with findings from the soft agar assays that mutants F59D and F59D/F66D were almost immotile (Fig. 4B) and indicate that the hydrophobic contacts on helix 5 of FliG were necessary for flagellar formation. From a homology model of E. coli FliFC–FliGN complex, we speculated that substitution of Glu62 with aspartate might allow hydrogen bond formation with Trp546 and help retain the FliF–FliG interaction when the hydrophobic contact at Phe59 or Phe66 is destroyed (Fig. S5). To test this, additional FliG mutants were created. These include E62D, E62K, F59D/E62D, F59D/E62K, E62D/F66D, E62K/F66D, and F59D/E62D/F66D. Our results showed that flagellation and motility were restored in F59D/E62D and E62D/F66D mutant strains. However, the results from the triple mutant strain F59D/E62D/F66D imply that hydrophobic contacts between FliF–FliG were essential for full flagellar formation and motility.

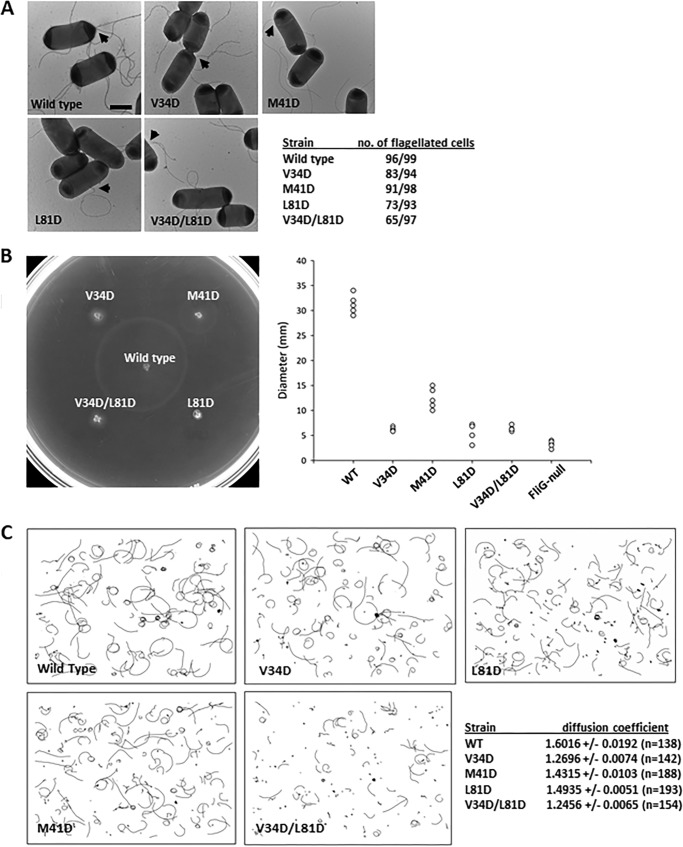

Figure 4.

The hydrophobic contacts between FliF and FliG were essential for flagellar assembly and full motility. A, electron micrographs of E. coli showing flagellar formation indicated by arrowheads in the wildtype and various complemented strains. Scale bar: 1 μm. B, wildtype and FliG complemented strains were spotted on 0.3% soft agar and incubated at 30 °C for 7 h, and the migration diameter was measured and plotted (n = 5).

FliF–FliG interaction was conserved across bacterial species

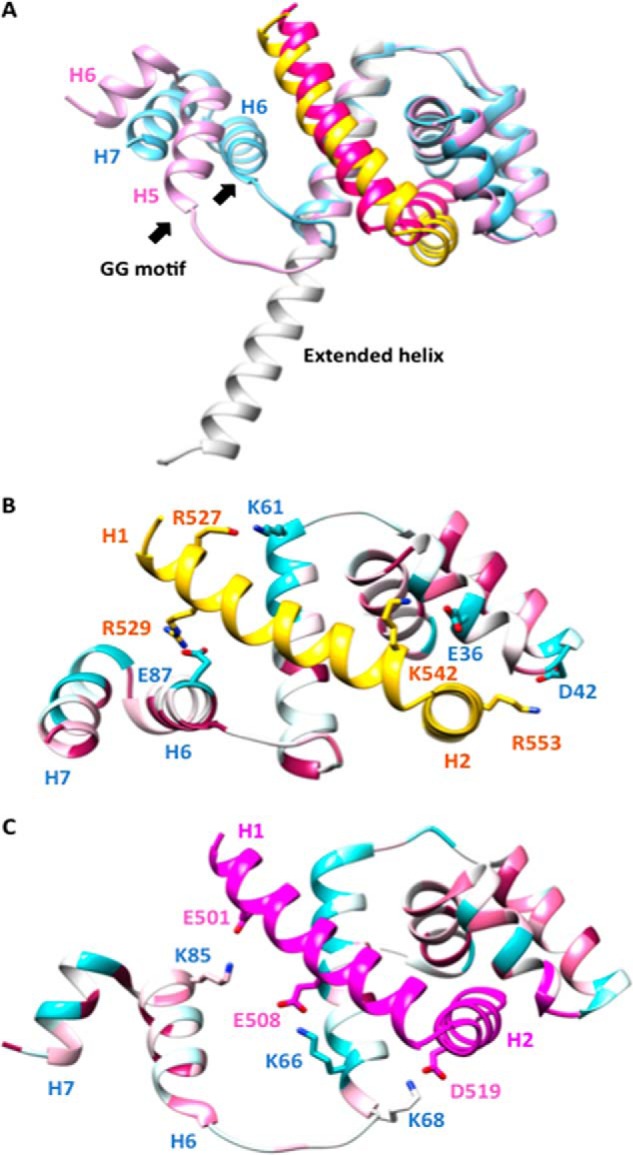

During the preparation of this manuscript, the structure of FliF–FliG from T. maritima was published (10). The structure was resolved at a resolution of 2.6 Å with two FliF–FliG heterodimers per asymmetric unit. The major difference between the two dimers was the conformation of the C-terminal helix in FliG; one had an extended structure and the other had three segmented helices (Fig. 5A). The structural comparison of the atomic models from T. maritima and our own FliF–FliG complex using the Dali server (16) revealed an r.m.s.d. of 1.4 Å and 2.9 Å over 35 residues of FliF in the two T. maritima FliF–FliG heterodimers. The structural alignment of both FliGs revealed a strong similarity including the presence of segmented helices, corresponding to helices 6–7 in the H. pylori structure (Fig. 5A) (r.m.s.d. of 2.9 Å over 104 aligned residues). Although both complexes contained similar interface areas where hydrophobic interactions dominated, different sets of salt bridges were involved. The salt bridges involved were scattered in different positions of the complexes (Fig. 5, B and C). For the four salt bridges in the H. pylori FliF–FliG complex, only one of them (Arg529FliF:Glu87FliG on helix 1 of FliF and helix 6 of FliG, respectively) could be found in a similar area in the T. maritima FliF–FliG complex (Glu501FliF:Lys85FliG), which highlights the importance of the relative orientations of helix 1 of FliF and helix 6 of FliG in the complex. None of the residues involved in the salt bridge formation were conserved. Except for the core hydrophobic patch, it is possible that the distinct electrostatic interactions were adopted by different bacteria to stabilize the FliF–FliG structure. The binding affinity of FliF–FliG in H. pylori was ∼10-fold lower than that of T. maritima, with a reported KD of <40 nm (9). The variation of affinities between the switch protein interacting partners among the different bacterial species was noted previously and might be related to the adaptation to different physiological environments (17).

Figure 5.

Structural comparison of the FliF–FliG complexes from H. pylori and T. maritima. A, superimposition of H. pylori FliF–FliG on the two heterodimers of T. maritima FliF–FliG. H. pylori FliF and FliG are colored in yellow and blue, respectively. T. maritima FliF and FliG are colored in magenta and pink, respectively. The extended helix in one of the heterodimers of the T. maritima FliG is colored in white. The conserved GlyGly motif at the beginning of helix 6 is indicated by arrows. B and C, salt bridges in the H. pylori FliF–FliG complex and T. maritima FliF–FliG complex. The structure of FliG is colored according to the sequence conservation score calculated by the ConSurf Server (26).

Assembly of FliGN ring through intermolecular stacking of ARM-like motif

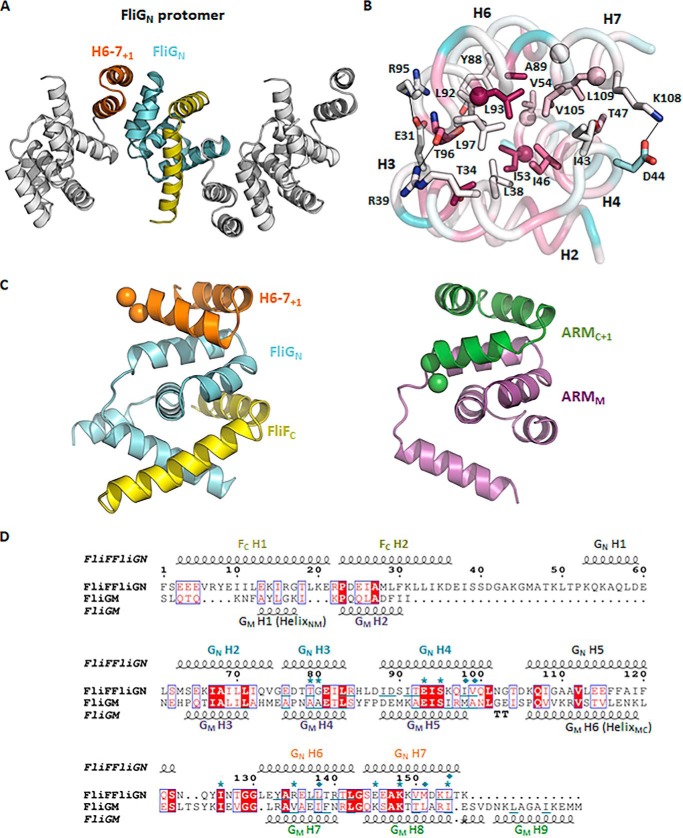

One important question that remains unresolved is the molecular basis of how FliGN associates with adjacent FliGN (10, 11). Remarkably, we found FliGN–FliFC organized as linear arrays, and adjacent molecules were packed in opposing orientations in the crystal lattice separated by ∼31 Å such that the ARMN interacted with helices 6–7 of the adjacent molecule (Fig. 6A). The protein–protein interaction buried a molecular surface area of ∼590 Å2 per molecule with a calculated free energy of ΔG = −10.8 kcal/mol (PDBePISA). This interaction was mostly mediated by the hydrophobic residues at helices 6–7+1 and the ARMN composed of conserved valine, isoleucine, and leucine at the core of the interface, which is a typical feature of ARM–ARM stacking (Fig. 6B). The charged residues at the periphery that contributed to electrostatic interactions were less conserved. The interaction shared remarkable similarity to the stacking of the ARMM–ARMC right-handed superhelices (Fig. 6C) (13–15). As noted, the complex structure of FliFC–FliGN shared high homology to FliGM. Helix 1 of FliF mimicked the HelixNM that connected the FliGN and FliGM domains, whereas helix 2 of FliF aligned well with helix 2 of FliGM (Fig. S3). In addition, FliGN contained an ARM-like domain (helices 6–7) and a flexible linker with a well-conserved Gly84-Gly85 motif that was structurally homologous to the way the ARMM connected to the ARMC through HelixMC (Fig. 6C). The structural similarity between these two domains (Fig. 6D) suggests that they could arise from gene duplication, as has been previously proposed (10, 18). The domains also shared the conserved function of mediating the assembly of FliG. We note that although the ARM-like domain in FliGN was shortened by one helix compared with ARMC and a typical ARM motif, it retained a similar topology for the formation of right-handed superhelices. We therefore argue that the interaction between the ARMN and the helices 6–7+1 was not a mere artifact of crystal packing. It was biologically important because FliGN formed a superhelix with adjacent FliGN molecules in a way similar to the ARMM–ARMC superhelix.

Figure 6.

The ARM-like motif of FliGN associated with helices 6–7, forming a functional unit that shared conserved structural topology with the ARM-like motif of the middle and C-terminal domains. A, a linear array of the FliGN–FliFC complexes in the crystal lattice. Adjacent complex molecules were arranged in opposite orientations. Helices 6–7 are colored in orange; the symmetry molecules are colored in white. B, the binding interface between helices 2–4 and helices 6–7+1 of FliGN. The residues mediating the hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions are shown as sticks. The corresponding residues that were most effectively cross-linked in E. coli (11) are shown as spheres. The structure is colored according to the sequence conservation score calculated by the ConSurf server (26). The sequence alignment was generated by randomly choosing 150 amino acid sequences from the server with sequence identity to FliG between 0.25 and 0.5. C and D, the structural alignment between the FliGN unit and ARMM–ARMC unit. The structural alignment was performed using the PROMALS3D web server (27), and the aligned sequence is represented by ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr) (28). (Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.) The conserved diglycine motif is shown as a sphere. The secondary structure of FliFC–FliGN and FliGM is drawn above and below the alignment, respectively. Identical amino acids are in red boxes. The conserved residues are highlighted in red. The residues involved in ARM-like packing are underlined. The FliG mutations that suppressed the clockwise rotational bias of E. coli expressing the FliF–FliG fusion protein are marked with asterisks. The cysteine mutation sites that were most effectively cross-linked are marked with a rhombus (11).

To demonstrate the in vivo relevance of the hydrophobic interaction between helices 6–7+1 and ARMN detected in the crystal lattice, we carried out complementation studies in E. coli. We mutated residues on helix 4 and helix 6 of FliG and studied their effects on flagellation and bacterial swimming. These residues include Ile46, Ile53, and Leu93, which are equivalent to residues Val34, Met41, and Leu81, respectively, in E. coli (Fig. 6B). Although most of the cells in the V34D, M41D, and L81D mutant strains were flagellates, the bacterial motility was significantly suppressed (Fig. 7, A and B). The percentage of flagellated cells was further reduced in the V34D/L81D mutant strain, suggesting that the hydrophobic surfaces of helices 4 and 6 were essential for proper flagellar assembly. To further clarify the effect of these mutations on motor function, we studied the swimming behavior by fixed-time diffusion analysis (15, 19). This method measures how close the swimming behavior of a bacterium is to pure diffusion. The diffusion coefficient of a tumbling bacterium is close to 1. For a bacterium that swims relatively straight, the diffusion coefficient is close to 2. We found a tumbling bias in all mutant strains, especially the strains that carried the V34D mutation (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these findings indicate that the hydrophobic surface of helices 4 and 6 of FliGN were critical for flagellar assembly and rotational switching. Our structural model of FliGN superhelices also agreed with a recent cross-linking study performed in E. coli, which demonstrated that most of the cysteine pairs are within 11 Å, and the flexibility of helix 6 enabled the cross-linking of cysteine pairs separated by a longer distance (11). Furthermore, the suppressor mutations for the clockwise rotational bias phenotype of a FliF–FliG fusion strain in E. coli were identified at this interface (11). Therefore, our structural model is more consistent with in vivo biochemical data for assembled FliG. FliFC–FliGN from T. maritima crystallized in two different conformations showed that the C terminus of helix 5 either adopted an extended α-helical conformation or formed three segmented helices (Fig. 5A) (10). Although the extended helix has been demonstrated to be the dominant conformation in solution, our structural and biochemical data suggest that the segmented helices' conformation was more relevant to the assembled state. The segmented helices' conformation of T. maritima was different from H. pylori in that no ARMN–helices 6–7 stacking was observed, in contrast to the ARMM–ARMC interaction that was found in all FliGMC structures. We note that the C-terminal portion of helix 7 of T. maritima FliGN was truncated, and Leu109 (H. pylori numbering) was removed. The interaction was likely weakened in the shortened construct. FliGC also shared similar topology to FliGM and FliGN, but it lacked the exposed hydrophobic surface and the C-terminal ARM-like motif for the FliG–FliG association. This conformation was likely related to the specialized function of FliGC that is involved in the charge–charge interaction with motility protein A (MotA). The ARMC is conventionally defined as belonging to the C-terminal domain, but the structural organization observed for our H. pylori FliG–FliG structure demonstrated that both FliGN and FliGM contained an ARM-like motif separated by a flexible loop for intermolecular association. Therefore, we suggest that ARMC should be reconsidered as part of the middle domain.

Figure 7.

The hydrophobic contacts in helices 4 and 6 in FliG were essential for motor assembly and function. A, the effect of FliG mutations V34D, M41D, L81D, and V34D/L81D on flagellar formation was examined by electron micrographs. The flagella are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar: 1 μm. B, soft agar assay. Wildtype and FliG complemented strains were spotted on 0.3% soft agar and incubated at 30 °C for 7 h. The migration diameters are plotted (n = 5). C, the swimming tracks of mutant strains used in the calculation of the diffusion coefficient. Swimming tracks of 4-s duration are plotted using the same scale.

Proposed model of FliFC–FliG ring

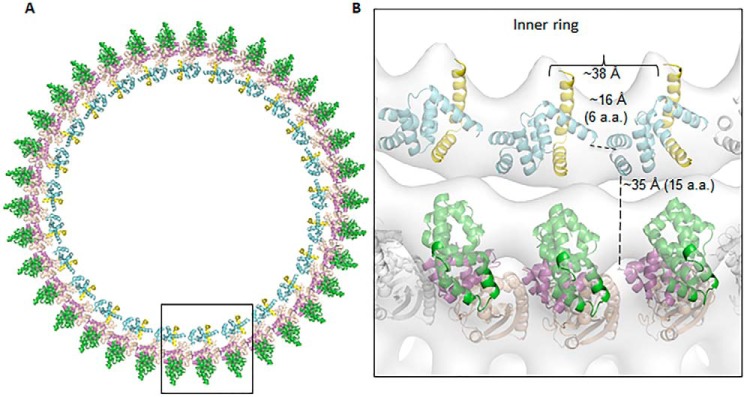

Collectively, we propose a FliFC–FliG ring model based on the repeating of FliGN superhelix in the inner ring and FliGM superhelix in the outer ring (Fig. 8). A 25-membered ring of FliFC–FliGN was generated by translation and docking to the MS–C ring map from S. typhimurium (2). The ring model was further fitted into the electron microscopy (EM) map, which was in good agreement with the rotor density with a correlation coefficient of 0.84 at 30 Å. The adjacent helices 5 and 6 were separated by ∼16 Å and were connected by a flexible six-residue linker. Similarly, the FliGMC was docked to the outer ring with 34-fold symmetry based on the previous model of H. pylori FliGMC (PDB ID: 3USW), and we calculated a correlation coefficient of 0.77. The C terminus of FliGN was separated from the N terminus of FliGM by ∼35 Å, and the HelixNM likely adopted an extended loop conformation to accommodate this distance. The HelixNM was likely to be flexible because most of the helix was invisible from our previous FliGMC structure (covering residues 86–343 of FliG) (PDB ID: 3USW), whereas the remaining visible part formed a distorted helical structure (15). In addition, the sequence alignment from multiple species showed that multiple glycines were identified within this region, hence its intrinsic flexibility (11).

Figure 8.

The proposed assembly model of FliFC–FliG in the MS–C ring complex. A, a single FliGN–FliF was manually docked to a low-resolution cryo-EM map from S. typhimurium and further optimized by the Fit to Map program in Chimera (25). The center of mass for the single complex was calculated, which had a distance of 167 Å from the center of map. The value was taken as the radius of the ring density and used for calculating the circumference of the ring. The rest of the molecules were generated by translation along the circumference of the ring to generate a 25-fold symmetry. The ring model was further fit into the EM map with a correlation coefficient of 0.84 at 30 Å. The outer ring model was generated by docking 34 molecules of the H. pylori FliGMC (PDB ID: 3USW) to the density map with a correlation coefficient of 0.76 (15). B, zoomed-in view of three FliFC–FliG units. The distances between the Cα of Asn78 and Gly85 linking helix 5 to helix 6 and between Lys111 and Ala126 connecting FliGN to FliGM are shown. The distance between the center of mass of the adjacent FliFC–FliGN model is also indicated.

One key question about the protein ring assembly is how the repeating protein molecules generated rings with different diameters. The HelixMC linking adjacent the FliGM has been suggested to adopt an extended loop structure as shown by a recent study, which could be important to explain the different symmetry of the inner and outer rings (11). Our structural model generally agreed with the hypothesis that the symmetry could arise from the different flexibilities of the loop connecting the adjacent ARM-like superhelix units in the inner and outer rings. The ARMN was linked to helices 6–7 via helix 5, which likely had limited flexibility because of interactions with FliFC. Therefore, the only flexibility allowed was a six-residue linker and a GlyGly motif restricting the adjacent ARMN in a smaller ring. By contrast, the ARMM and ARMC were linked by the HelixMC. The HelixMC was more flexible, as indicated by the different conformations in different lattices of FliG structures that could allow it to extend to rings with larger diameters. The assembly model presented here is similar to the model proposed by Lynch et al. (10) in which the inner C ring is composed of 25 molecules of FliFC–FliGN modules that have the N terminus of FliFC pointing toward the inner membrane (10). Adding or deleting one FliFC–FliGN unit did not fit the ring density or cause steric clashes. There are two major differences between these two models. The previous model was constructed based on the assumption of an extended helix conformation of FliGN, and the adjacent FliFC–FliGN molecules were separate units that did not interact. We showed that the adjacent FliFC–FliGN molecules were connected through helices 6–7 in a segmented helix conformation and explained how they formed a continuous protein ring that functioned coherently through noncovalent interactions. Together, the different positioning of helices 6–7 and the spatial restraint imposed on the C terminus of helix 7 by the linker connecting FliGMC caused the orientations of FliGN molecule between the two models to differ by almost 180° in the axis perpendicular to the ring. The difference can be explained by the C terminus of helix 7 pointing to the side opposite to the N terminus of FliF, but they were on the same face in the T. maritima model.

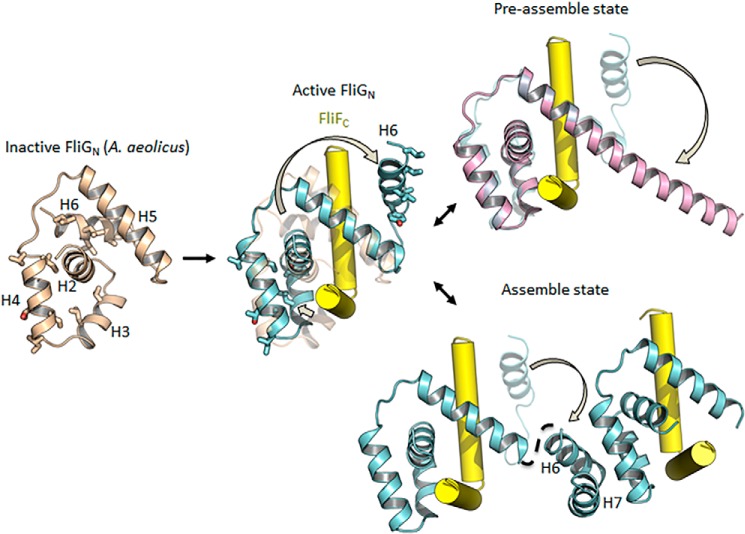

FliF-binding induced conformational change of FliGN preceding FliG assembly

The exposed hydrophobic surfaces of FliG were energetically unfavorable and posed a threat to nonspecific protein aggregation. The hydrophobic surfaces of ARMM and ARMC were buried in solution by intramolecular stacking (20). The interacting surfaces were only exposed when FliG was assembled on the ring that interacted with adjacent molecules through a domain-swapping mechanism. In contrast to the ARMM and ARMC, which are connected by a long and flexible linker, the short length of the loop between helix 5 and helices 6–7 of FliGN prevented intramolecular associations. The comparison of the FliGN domain of the H. pylori FliGN–FliFC structure with that of A. aeolicus FliG, the only apo FliG structure available, revealed an alternative strategy to prevent the premature solvent exposure of hydrophobic residues of FliGN (Fig. 9). FliGN of A. aeolicus was folded in a closed conformation, and thus the hydrophobic residues mediating the intersubunit-binding at helices 3–4 and 6 were partially buried by interacting with helices 2 and 5. The dramatic changes of helices 2–3 and 6 generated a central cleft for FliF-binding, formed the hydrophobic ARM-like docking platform, and kicked helix 6 into a position that caused it to be exposed to solvent. Therefore, the complementary surfaces of the ARMN and helices 6–7 were likely formed only after FliF-binding. The formation of the FliGN-FliFC complex induced extensive conformational changes in FliGN, which is supported by previous NMR data (9, 10) and suggests the conformational transition was conserved across the bacterial species. Helix 6 was flexible in solution, which could indicate that the transition from the closed to open state had a low energy cost. In the context of the MS–C ring, the exposed ARMN and FliGN would be immediately stabilized by adjacent FliG molecules, forming a coherent ring through noncovalent interactions.

Figure 9.

FliF-binding initiated the conformational transition of FliGN for self-assembly. A model of apo FliGN was generated by Morph conformation (Chimera) (25) by using FliG from A. aeolicus (PDB ID: 3HJL) as a template, and the resultant model was energy minimized. The residues involved in hydrophobic interactions between ARMN and helices 6–7 are shown as sticks. The conformational changes of helices 2–4 and 6 upon FliFC-binding lead to the exposure of hydrophobic residues, forming the complementary surface for interactions similar to the ARM repeat motif.

In summary, our findings suggest a possible mechanism for the multistep assembly of the MS–C ring (Fig. 9). During preassembly, FliG existed as a monomer, and the hydrophobic surfaces of the ARM domains were shielded from solvent exposure (13, 14, 20). Upon the binding of the two C-terminal helices of FliF, the sequential conformational changes of FliG spreading from the N terminus to the C terminus were triggered. Helices 2–3 rearranged to accommodate the tight binding of FliF, whereas helix 6 was swung out. The free helix 6 of FliG sampled different conformational states, likely dominated by forming a helical structure continuous with helix 5 as supported by a previous solution study (10). Further docking of a nearby FliG molecule to FliF stabilized and promoted the association of the ARMN with helices 6–7, formed the inner C ring, and caused the breakage of HelixNM to form an extended conformation (11). The adjacent ARMC and ARMM were in close proximity after the assembly of FliGN molecules and interacted to form the outer ring through domain swapping (20). The ring assembly was further stabilized by FliM and FliN at the base of the C ring. The tight binding between FliFC and FliGN allowed for the secure placement of the 3-megadalton motor switch complex and anchored it to the inner membrane, and the binding also provided a driving strength capable of transmitting the signals from the FliG middle and C-terminal domains to the rod and filament for flagellar rotation and switching.

Experimental procedures

Expression and purification of FliF–FliG complex plasmids

The C-terminal fragment of FliF (residues 484–567) from H. pylori (strain 26695) was cloned into the pAC28 vector, which included an N-terminal His-tag. The N-terminal domain of FliG (residues 1–115) was cloned into the pGEX-6P-2 vector, which contained an N-terminal GST-tag. The constructs were verified by sequencing. The two recombinant plasmids were cotransformed into BL21 E. coli cells, and the expression of FliF and FliG was induced by 0.2 mm IPTG at A600 of 0.5. The cells were further incubated at 20 °C overnight. The bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 20 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mm Tris, 300 mm NaCl, and 20 mm imidazole at pH 7.8 and was lysed by sonication. The clear lysate was filtered and loaded onto nickel agarose equilibrated with the lysis buffer. The column was washed, and the protein was eluted in a lysis buffer containing a gradient of 100–250 mm imidazole. The eluate was further purified by glutathione Sepharose equilibrated with the lysis buffer at pH 7.5. After immobilization and washing, the GST-tag was cleaved by PreScission Protease overnight at 4 °C. The flow-through containing the FliF–FliG complex was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using Superdex 75 (16/60) equilibrated with 20 mm Tris and 300 mm NaCl. The protein was concentrated to 7.3 mg/ml for the crystallization study.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystallization trials were set up in 96-well Greiner plates using sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Oval-like FliF–FliG crystals were obtained after 6 months in mother liquor containing 0.1 m sodium citrate tribasic dehydrate pH 5.6, 20% v/v 2-propanol, 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 4000 of the Crystal Screen (Hampton Research). The crystallization condition was further optimized by in situ proteolysis (21). Trypsin was added to the concentrated protein sample to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml before setting the crystallization droplet. The selenomethionine-labeled crystals were prepared using the FliF–FliG protein complex co-expressed in B834 E. coli cells cultured in selenomethionine medium complete (Molecular Dimensions). The crystals were cryoprotected in 20% glycerol and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The diffraction data up to 2.3 Å for a native crystal were recorded at 100 K on the BL13B beamline at National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, Taiwan. A 2.7 Å SAD dataset at the selenium absorption edge was collected at the same beamline. The native data were processed with iMosflm and scaled with Scala in CCP4 suite (22). The SeMet derivative data were processed by HKL2000 and scaled with Scalepack. The crystals were in the P3221 space group with one FliF–FliG complex per asymmetric unit.

Structure determination and refinement

The structure of FliF–FliG was solved by SAD using Phenix AutoSol (23). Four selenomethionine sites in the asymmetric unit were located and used for phase determination and improvement, which yielded a traceable electron density map. Initial model building was performed by Phenix AutoBuild, and the phase was then applied to the native dataset. Iterative rounds of refinement using Phenix (23) with translation–libration–screw rotation (TLS) parameters and manual building in Coot (24) resulted in a model containing FliF starting at residue 523 and ending at residue 559, and FliG starting at residue 7 and ending at residue 111. There was no electron density map for residues 484–521 and 560–567 of FliF, and residues 1–6 and residues 112–115 of FliG. Therefore, these residues were not included in the model. Table S1 shows the refinement and geometry statistics. All structure presentations were drawn by Chimera (25). The structure has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB ID: 5WUJ.

Mutagenesis and pulldown assay

To validate the binding interface revealed from the crystal structure, various single and multiple point mutations were introduced to FliFC. The co-expression of His-tagged FliFC and GST-tagged FliGN in BL21 E. coli cells was performed as described above. After harvesting and cell lysis, the formation of FliFC and FliGN complexes were examined by pulldown assay. The control experiment was set using co-expression of FliFC and GST. The clear lysate was incubated with glutathione Sepharose for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing with 1 ml of lysis buffer three times to remove the unbound proteins, the Sepharose was resuspended in a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Static light scattering

The purified FliFC, FliGN, and FliFC–FliGN complex were subjected to static light scattering using a miniDAWN triangle (45°, 90°, and 135°) light-scattering detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA) connected to an Optilab DSP interferometric refractometer (Wyatt Technology). This system was connected to a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) controlled by an ÄKTA explorer chromatography system (GE Healthcare). Before sample injection, the miniDAWN detector system was equilibrated with 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris pH 7.5 for at least 2 h to ensure a stable baseline signal. The flow rate was set to 0.5 ml/min, and the sample volume was 100 μl. The laser scattering (687 nm) and the refractive index (690 nm) of the respective protein solutions were recorded. Wyatt ASTRA software was used to evaluate all obtained data.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

The interaction between FliFC and FliGN was measured using a MicroCal iTC200 calorimeter (GE Healthcare) as previously described (17). The protein samples were first purified by affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration chromatography with an isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) buffer containing 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 50 mm HEPES pH 7.5. The experiment was performed using MicroCal iTC200 with the sample cell loaded with 50 μm FliGN and the syringe filled with 480 μm FliFC. The experiment was carried out by initially injecting 0.2 μl followed by 19 1.8-μl injections with 180-s spacing. The heat of dilution was measured by injecting the buffer into FliGN, which was subtracted from the raw data. The control experiment was performed by injecting FliFC into the buffer, which caused an insignificant effect on the heat of dilution. The data were analyzed and the thermodynamic parameters were obtained using Origin software. The heats were integrated and fit into a 1:1 binding model.

Complementation studies in E. coli

The cDNA encoding E. coli FliG (EcFliG) from strain RP437 (a gift from J. S. Parkinson) was amplified and cloned into expression vector pTrc99a. The construction of EcFliG mutants was performed according to the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent). The constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. pTrc99a–EcFliG and its mutants were individually transformed into E. coli ΔfliG strain DFB225 for complementation.

Electron microscopy

Flagellar formation of E. coli ΔfliG strain transformed with wildtype or mutant EcFliG was examined using transmission electron microscope by negative staining. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline three times, the cells were stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate on a Formavar/carbon–coated grid (Ted Pella, Inc.). Flagellation was examined at 80 kV by a Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscope.

Swarming assay

After being transformed with wildtype or mutant pTrc99a-EcFliG, the E. coli ΔfliG strain DFB225 was grown in lysogeny broth (LB) medium overnight. Tryptone broth (0.3%) soft agar with 0.05 mm IPTG and 100 μg/ml ampicillin was prepared for swarming assay. A 1-μl cell suspension was spotted onto the soft agar. The diameters of the swarming rings were measured after incubation at 30 °C for 7 h.

Swimming assay

An overnight culture of the transformed DFB225 was diluted with 1:50 tryptone broth medium. The bacterial cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 1.5 h followed by addition of 0.05 mm IPTG for induction. The cells were harvested at exponential phase and washed twice with chemotaxis buffer (10 mm sodium phosphate at pH 7.0, 0.05 mm EDTA and 1 mm methionine). The cell suspension was diluted to A600 of 0.1. The swimming behavior was recorded with a phase contrast-inverted microscope (Olympus IX71), and 10-s videos at a frame rate of 15 frames per second and a resolution of 1360 × 1024 pixels were collected. The videos were imported to ImagePro Plus for analysis. For each frame, the center-of-area (centroid) of each bacterium was automatically determined and connected to form a track. The XY positions of the centroid and the tracks of each frame were exported into an Excel spreadsheet. The tracks were then analyzed by the fixed-time diffusion method (19) to determine the diffusion coefficient. Briefly, the tracks were truncated into 4 s. All the (X(0),Y(0)) values were subtracted from the (X(t),Y(t)) positions so that all the tracks started from the same origin. The coordinates were then transformed into polar coordinates (r(t), θ(t)), and the mean square radius < R2(t)> for each time point was calculated. The diffusion coefficient α was determined from the slope of the plot of log < R2(t)> against log(t), according to the equation: < R2(t) > = Dtα, where D is the diffusion constant. The statistical significance was calculated using a one-tailed Student's t test, and results were considered significant for p < 0.01.

Author contributions

K. H. L. and S. W. N. A. conceived and designed the experiments; C. X., K. H. L, H. Z., K. S, S. H. L., and X. C. performed the experiments; K. H. L. and S. W. A analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at beamline 13B1 of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Centre, Taiwan, for their support and assistance. We also thank Prof. J. S. Parkinson for the E. coli wildtype and fliG-null strains, Helen Tsai for the mass spectrometry analysis, and Profs. Michael Chan and Marianne Lee for proofreading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the General Research Fund Project Grant 460112 and NSFC-RGC Joint Research Scheme Project Grant N_CUHK454/13, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong, and the Direct Grant from The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 5WUJ) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- ARM

- armadillo repeat

- SAD

- single-wavelength anomalous diffraction

References

- 1. Thomas D. R., Morgan D. G., and DeRosier D. J. (1999) Rotational symmetry of the C ring and a mechanism for the flagellar rotary motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 10134–10139 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas D. R., Francis N. R., Xu C., and DeRosier D. J. (2006) The three-dimensional structure of the flagellar rotor from a clockwise-locked mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7039–7048 10.1128/JB.00552-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown P. N., Terrazas M., Paul K., and Blair D. F. (2007) Mutational analysis of the flagellar protein FliG: Sites of interaction with FliM and implications for organization of the switch complex. J. Bacteriol. 189, 305–312 10.1128/JB.01281-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Francis N. R., Irikura V. M., Yamaguchi S., DeRosier D. J., and Macnab R. M. (1992) Localization of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar switch protein FliG to the cytoplasmic M-ring face of the basal body. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6304–6308 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grünenfelder B., Gehrig S., and Jenal U. (2003) Role of the cytoplasmic C terminus of the FliF motor protein in flagellar assembly and rotation. J. Bacteriol. 185, 1624–1633 10.1128/JB.185.5.1624-1633.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marykwas D. L., Schmidt S. A., and Berg H. C. (1996) Interacting components of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli revealed by the two-hybrid system in yeast. J. Mol. Biol. 256, 564–576 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kubori T., Yamaguchi S., and Aizawa S.-I. (1997) Assembly of the switch complex onto the MS ring complex of Salmonella typhimurium does not require any other flagellar proteins. J. Bacteriol. 179, 813–817 10.1128/jb.179.3.813-817.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas D., Morgan D. G., and DeRosier D. J. (2001) Structures of bacterial flagellar motors from two FliF-FliG gene fusion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6404–6412 10.1128/JB.183.21.6404-6412.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levenson R., Zhou H., and Dahlquist F. W. (2012) Structural insights into the interaction between the bacterial flagellar motor proteins FliF and FliG. Biochemistry 51, 5052–5060 10.1021/bi3004582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lynch M. J., Levenson R., Kim E. A., Sircar R., Blair D. F., Dahlquist F. W., and Crane B. R. (2017) Co-folding of a FliF-FliG split domain forms the basis of the MS:C ring interface within the bacterial flagellar motor. Structure 25, 317–328 10.1016/j.str.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim E. A., Panushka J., Meyer T., Carlisle R., Baker S., Ide N., Lynch M., Crane B. R., and Blair D. F. (2017) Architecture of the flagellar switch complex of Escherichia coli: Conformational plasticity of FliG and implications for adaptive remodeling. J. Mol. Biol. 429, 1305–1320 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kihara M., Miller G. U., and Macnab R. M. (2000) Deletion analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliG of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3022–3028 10.1128/JB.182.11.3022-3028.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee L. K., Ginsburg M. A., Crovace C., Donohoe M., and Stock D. (2010) Structure of the torque ring of the flagellar motor and the molecular basis for rotational switching. Nature 466, 996–1000 10.1038/nature09300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Minamino T., Imada K., Kinoshita M., Nakamura S., Morimoto Y. V., and Namba K. (2011) Structural insight into the rotational switching mechanism of the bacterial flagellar motor. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000616 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lam K.-H., Ip W.-S., Lam Y.-W., Chan S.-O., Ling T. K.-W., and Au S. W.-N. (2012) Multiple conformations of the FliG C-terminal domain provide insight into flagellar motor switching. Structure 20, 315–325 10.1016/j.str.2011.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holm L., and Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: Conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 10.1093/nar/gkq366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lam K. H., Lam W. W. L., Wong J. Y. K., Chan L. C., Kotaka M., Ling T. K. W., Jin D. Y., Ottemann K. M., and Au S. W. N. (2013) Structural basis of FliG–FliM interaction in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 88, 798–812 10.1111/mmi.12222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu R., and Ochman H. (2007) Stepwise formation of the bacterial flagellar system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7116–7121 10.1073/pnas.0700266104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowenthal A. C., Hill M., Sycuro L. K., Mehmood K., Salama N. R., and Ottemann K. M. (2009) Functional analysis of the Helicobacter pylori flagellar switch proteins. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7147–7156 10.1128/JB.00749-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker M. A. B., Hynson R. M. G., Ganuelas L. A., Mohammadi N. S., Liew C. W., Rey A. A., Duff A. P., Whitten A. E., Jeffries C. M., and Delalez N. J. (2016) Domain-swap polymerization drives the self-assembly of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong A., Xu X., Edwards A. M., Chang C., Chruszcz M., Cuff M., Cymborowski M., Di Leo R., Egorova O., and Evdokimova E. (2007) In situ proteolysis for protein crystallization and structure determination. Nat. Meth. 4, 1019–1021 10.1038/nmeth1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G. W., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., and Wilson K. S. (2011) Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 10.1107/S0907444910045749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., Oeffner R., Read R.J., Richardson D.C., Richardson J.S., Terwilliger T.C., and Zwart P.H. (2010) PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emsley P., and Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ashkenazy H., Abadi S., Martz E., Chay O., Mayrose I., Pupko T., and Ben-Tal N. (2016) ConSurf 2016: An improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W344–W350 10.1093/nar/gkw408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pei J., Kim B.-H., and Grishin N. V. (2008) PROMALS3D: A tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2295–2300 10.1093/nar/gkn072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robert X., and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.